Abstract

Dideoxypetrosynol A is a C30 polyacetylenic alcohol with C2 symmetry. The first total synthesis of both enantiomers of the potent anti-cancer natural product (+)- and (−)-dideoxypetrosynol A is reported. The key step is an oxidative coupling of a homopropargyl phosphonium ylide to prepare the “skipped” (Z)-enediyne moiety. The natural dideoxypetrosynol A was isolated as a racemic mixture as shown in structure 1. The absolute configurations of the chiral centers are established for the (+)- and (−)-enantiomers using Burgess’ enzymatic resolution procedure with Pseudomonas AK lipase.

Keywords: Total synthesis, anticancer, natural product, (Z)-enediyne

Introduction

Along with three similar polyacetylenic alcohols, dideoxypetrosynol A (1) was isolated by Jung and co-workers off the Komun Island, Korea from the marine sponge Petrosia sp. guided by a brine shrimp assay.[1] These compounds have structural features related to duryne (2)[2] and petrosynol (3),[3, 4] both of which have been found to posses anti-cancer and other interesting biological activities.[5] Dideoxypetrosynol A (1) was also found to have potent anticancer activity and exhibited an ED50 of 0.02 μg/mL against human ovarian cancer cells and of 0.01 μg/mL against human skin cancer cells.[1] It is noteworthy that the cytotoxic activities of compound 1 is one order of magnitude higher than those found for doxorubicin, which is one of the most commonly used chemotherapeutic drugs and exhibits a wide spectrum of activity against solid tumors, lymphomas, and leukemias.[6] Dideoxypetrosynol A (1) was also found to inhibit DNA replication at the initiation stage.[7] However due to the minute yield (23 mg out of 14.5 kg of dry sponge) from the natural source, only limited studies of biological activity have been performed. To the best of our knowledge, no synthetic study of dideoxypetrosynol A has been reported.

Recently we reported a total synthesis of duryne (2) and assigned the geometry of the central C=C olefin and the absolute stereochemistry of the chiral centers.[8] Although the structures of compounds 1 and 2 are similar, the central (Z)-enedipropargyl moiety (which was first coined the “skipped” enediyne by Gleiter)[9] in 1 posed a new problem for an efficient synthesis. Here we are pleased to report a successful total synthesis of dideoxypetrosynol A with an oxidative coupling strategy to prepare the “skipped” enediyne moiety.

Results and Discussion

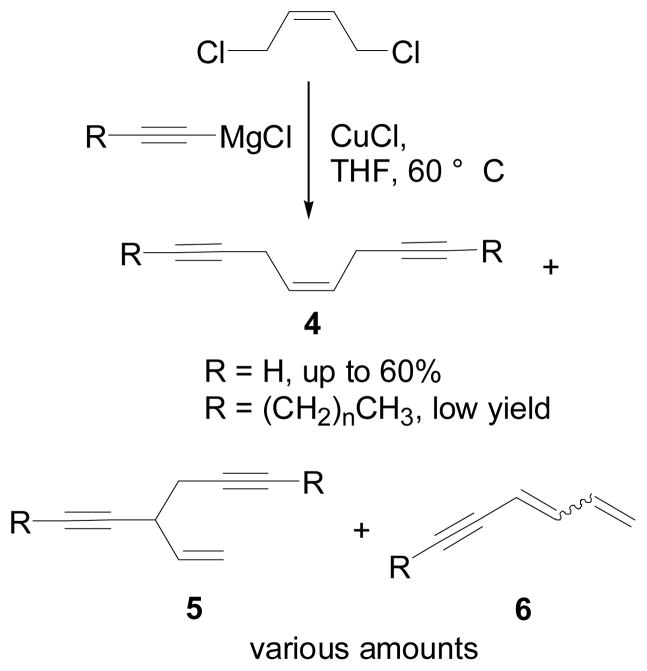

Current literature method for constructing the “skipped” (Z)-enediyne system such as compound 4, Scheme 1, is an SN2 alkylation of (Z)-1,4-dichloro-2-butene with a Grignard reagent made from alkyne.[9–11] The concurrent formation of the SN2′ product (5) and the elimination product (6), as shown in Scheme 1, are the main problems for this approach. So far only poor yields have been reported.[11, 12]

Scheme 1.

Results from the Existing method

Gleiter and Merger reported an improvement of yield from 20% to 60% by using ethynyl magnesium chloride in stead of ethynyl magnesium bromide.[9] Unfortunately reactions of long chain alkynylmagnesium chloride did not seem to give any better yields.[11, 12] In our hands, little of the desired product was obtained when using the alkynylmagnesium chloride reagent prepared from compound 12 (see Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of dideoxypetrosynol A

We turned our attention to an alternate strategy after failing to improve the yields with the alkynylation of cis-1,4-dichloro-2-butene. In our recent effort in the synthesis of duryne (2),[8] the (Z)-geometry of the central double bond was established by an autooxidation of the Wittig reagent (7) generated in situ as reported by Poulain and co-workers, eq. 1.[13] The reaction mixture was saturated with oxygen before refluxing for 16 h to produce cis olefin 8.[14] However, when the same condition was applied to phosphonium salt 9a in an attempt to prepare cis-olefin 11a, the only identifiable product was the enyne 10, along with mixtures of unidentified products, eq. 2. It appeared that a proton abstraction from the propargylic position, at least in part, had occurred in compound 9a when sodium hexamethyldisilazide (NaHMDS) was used as the base in the reaction. The most acidic proton in phosphonium salt 9a should be the CH2 attached to the positively charged phosphorous atom (Ph3P+CH2, pKa ~ 22).[15] However the adjacent propargylic CH2 in compound 9a could lose a proton to give the elimination product 10. Propargylic CHs are well known to be acidic and amide bases have been used to remove propargylic protons,[16–18] though there is little data to be found concerning the pKa of propargylic CHs.[19] Propargylithium is known to have an allene-like structure,[20] suggesting that propargylic CHs are less acidic than allenylic CHs, which is consistent with gas phase acidity orders of allene and propyne.[21] Thus the CH2 bonded to the positively charged phosphorous atom in 9a should be more acidic than the propargylic CH2. Therefore it should be possible to selectively remove the Ph3P+CH2 proton in compound 9a. A survey of different bases was performed and the results are shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Base effect on Wittig reagent formation and oxidative coupling

|

eq (1) |

|

eq (2) |

The use of n-butyllithium in place of NaHMDS led to a much better yield of the desired product 11b than the SN2 alkynylation procedure shown in Scheme 1. Interestingly, the less strong bases are all inferior in this reaction compared to n-butyllithium. A previous report also indicated that n-butyllithium gave smooth formation of the desired Wittig reagent on a similar phosphonium salt.[22] Based on these observations, the formation of the by products such as enyne 10 might be due to (1) the steric bulk of the base used and (2) the reversibility of the deprotonation step when the less strong bases such as NaHMDS are used. Thus a significant amount of the elimination product 10 could occur through a shift of the reaction equilibrium even only a small percentage of the propargylic proton was initially removed. The following elimination and the formation of enyne 10 are not reversible. This explains why enyne 10 was produced when KOBu-t and NaHMDS were used.

When the reaction was performed in a mixed solvent system containing methanol, the homopropargyl diphenylphosphine oxide 11c was produced in 88% yield. The formation of 11c did not require the presence of oxygen. It is presumably formed through a CH3O-attack on the phosphonium salt at the phosphorous atom followed by protonation of a phenyl anion and an SN2 attack on the resulting Ph2RP=O+-CH3 by a CH3O-group.

Once we found the proper base to use in the preparation of the Wittig reagent, the synthesis of the target started with the known terminal acetylene 12, Scheme 3.[23] Homopropargyl alcohol 13 was prepared following a procedure reported by Brummond.[24] This procedure employs Me3Al as an additive in the ethylene oxide opening reaction and gives a reproducible yield of the desired product. Compound 13 was converted to the homopropargyl bromide by a modification of the Appel reaction.[25] The preparation of the phosphonium salt 9a (eq. 2) follows the reported procedure by Dawson.[26] n-BuLi treatment of 9a followed by saturating the reaction mixture with oxygen and reflux in THF produced the cis-enediyne 11a in 86 % yield. With the key intermediate 11a in hand, dial 15 was obtained through a two step sequence: (1) removal of the TBS protecting group with TBAF in THF and (2) PCC oxidation of the resulting diol, Scheme 3. The Wittig reaction of the dialdehyde with Ph3P=CHCHO yielded a α,β-unsaturated dial and the addition of acetylenic magnesium bromide to the dial produced the racemic natural product 1. Although the natural product dideoxypetrosynol A was reported as a possible racemic mixture, it was unclear whether racemization had occurred during the isolation-identification process.[1] It is important to identify the efficacy of each enantiomer’s action on cancer cells. Therefore we decided to carry out an enzymatic resolution to assign the absolute configurations to each enantiomer.

The general procedures of Burgess were followed using lipase AK from pseudomonas sp for the enzymatic resolution of the acetylenic alcohol 1.[27, 28] The progress of the reaction was followed by both thin layer chromatography and 1H NMR to ensure a clean kinetic resolution of the enantiomers. The separation of the diacetate 16, the meso monoacetate 17, and the diol (−)-1 was done by column chromatography.

(R,R)-Diol 1 has a negative optical rotation of [α]D −40.4 °. The removal of the acetate group from 16 yields (S,S)-diol 1, which gives a positive optical rotation of [α]D +41.3 °. The assignment of the absolute configurations is based on Burgess active site model for the lipases from Pseudomonas sp.[27] This model predicts that alcohols resolved most efficiently have one small and one relatively large group attached to the hydroxylmethine carbon. Dideoxypetrosynol A (1) is similar in structure to several C2-symmetric polyacetylenic alcohols including adociacetylene, duryne, and a C20 acetylenic alcohol, all of which we have successfully resolved using lipase from Pseudomonas sp.[8, 23, 29] For most secondary alcohols, the rate of acylation is faster for the (R)-configuration than for the (S)-configuration. However, for the acetylenic alcohol 1, the isomer with (S, S) configuration is acylated faster because the small acetylenic group has a higher priority in the nomenclature system. From these considerations and the data obtained, we assign the (3S, 28S) configurations to the enantiomer with a positive optical rotation and the (3R, 28R) to the enantiomer with a negative optical rotation. To corroborate this assignment, several known C2 symmetric acetylenic alcohols isolated from marine sources16–19 are listed below for comparison purpose.

Conclusions

A total synthesis of the potent anticancer polyacetylenic alcohol dideoxypetrosynol A (1) has been achieved. The key step involves the coupling of a homopropargyl phosphonium ylide to produce the cis- “skipped” enediyne moiety. n-Butyllithium was found to be the most effective base in the preparation of the Wittig reagent from the triphenylphosphonium salt containing a homopropargyl substituent. Two directional synthesis is executed in the remaining steps to obtain the racemic polyacetylenic natural product 1 in an efficient 8 steps and 33.7% overall yield starting from the known compound 12. The absolute configurations of the (+)- and (−)-dideoxypetrosynol have been established through the total synthesis of 1 and the subsequent enzymatic resolution of the racemic mixture.

Experimental Section

All reactions were carried out under an atmosphere of nitrogen in oven-dried glassware with magnetic stirring. Reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used directly without further purification. Purification of reaction products was carried out by flash chromatography using silica gel 40–63 μm (230–400 mesh), unless otherwise stated. Reactions were monitored by 1H NMR and/or thin-layer chromatography. Visualization was accomplished with UV light, staining with 5% KMnO4 solution followed by heating. Chemical shifts are recorded in ppm (δ) using tetramethylsilane (H, C) as the internal reference. Data are reported as follows: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet; integration; coupling constant(s) in Hz.

11-(tert-Butyl-dimethyl-silanyloxy)-undec-3-yn-1-ol (13)

To a solution of the alkyne 12 (2.45 g, 9.6 mmol) in THF (10 mL) at −78 °C was added n-BuLi (7.2 mL, 11.5 mmol) dropwise. After 45 minutes the flask was placed in an ice bath for 15 minutes then Me3Al (1 mL, 1.92 mmol) was added followed by ethylene oxide (0.6 mL, 11.5 mmol). The ice bath was removed and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 36 h after which it was quenched by the addition of H2O and ether. The biphasic mixture was transferred into a separatory funnel and 10% HCl was added until it eliminated the aluminum emulsion. The aqueous layer was extracted using EtOAc. The combined organics were dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Purification was effected via column chromatography to afford 13 as clear oil (2.2 g, 78%): IR 1045, 1097, 1254, 1471, 2244, 2856, 2929, 3380 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 0.02 (s, 6 H), 0.86 (s, 9 H), 1.27–1.49 (m, 10 H), 1.81 (br, 1 H), 2.13 (t, 2 H, J = 2.3 Hz), 2.41 (t, 2 H, J = 4.1 Hz), 3.58 (t, 2 H, J = 6.7 Hz), 3.66 (dt, 2 H, J = 6.2, 4.3 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 0.04, 18.4, 18.7, 23.4, 23.2, 25.6, 25.9, 28.8, 28.9, 32.8, 61.3, 63.2, 76.3, 82.5; ; HRMS calcd for C17H34O2Si (M+Na) 321.2226, found 321.2204.

(11-Bromo-undec-8-ynyloxy)-tert-butyl-dimethyl-silane (14)

A reaction mixture containing 13 (2.2 g, 7.34 mmol) in dry THF (18 mL) was treated with Ph3P (3.9 g, 14.68 mmol), dry pyridine (0.6 mL, 7.34 mmol) and CBr4 (2.42 g, 7.34 mmol). After stirring for 4 h at room temperature the reaction mixture was diluted with H2O and the aqueous solution was extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic solution was washed with 1M HCl, H2O and brine in that order. This was then dried (MgSO4) filtered and concentrated in vacuo. The resulting oil was triturated with hexanes and the combined washings were concentrated in vacuo. Purification was effected via column chromatography to give 14 as clear oil (2.4 g, 86%): IR 1005, 1097, 1253, 1471, 2856, 2928 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 0.02 (s, 6 H), 0.86 (s, 9 H), 1.27–1.45 (m, 10 H), 2.12 (t, 2 H, J = 2.3 Hz), 2.69 (t, 2 H, J = 5.1 Hz), 3.38 (t, 2 H, J = 7.4 Hz), 3.57 (dt, 2 H, J = 6.6 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 0.04, 18.4, 18.7, 23.4, 25.7, 25.9, 28.7, 28.8, 28.9, 30.3, 32.8, 63.2, 77.3, 82.7.

1,22-Bis-(tert-butyl-dimethyl-silanyloxy)-docos-11-ene-8,14-diyne (11a)

A solution of 14 (2.4 g, 6.4 mmol) and Ph3P (1.65 g, 6.4 mmol) in CH3CN (15 mL) was stirred at reflux for 16 h and then concentrated under reduced pressure to afford the crude product which was triturated with hexanes several times to afford 9a (3.2 g, 88%): IR 1110, 1254, 1437, 1471, 1587, 1824, 2176, 2855, 2928, 3055 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 0.02 (s, 6 H), 0.86 (s, 9 H), 1.12–1.26 (m, 8 H), 1.57 (t, 2 H, J = 2.1 Hz), 1.67 (br, 2 H), 2.81 (brd, 2 H), 3.57 (t, 2 H, J = 6.6 Hz), 4.12 (dt, 2 H, J = 12.2, 6.3 Hz) 7.67 (dd, 6 H, J = 7.9, 3.4 Hz), 7.85 ( dt, 3H, J = 8.2, 4.2 Hz), 7.88 (dt, 6 H, J = 8.5, 7.35 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 0.04, 13.2, 18.3, 18.4, 22.6, 23.0, 25.7, 25.8, 25.9, 28.3, 28.8, 32.8, 63.2, 76.9, 85.4, 128.7, 130.2, 130.3, 133.9, 134.9.

A solution of 9 (2.2 g, 3.91 mmol) in THF (20 mL) under N2 was cooled to 0 °C followed by dropwise addition of n-BuLi (2.44 mL, 3.91 mmol) via a syringe. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 2 h then warmed to room temperature and stirred for a further 1 h and then oxygen was bubbled into the reaction mixture. Stirring was continued at 60 °C for 16 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with saturated NH4Cl and the mixture poured into H2O. Purification was effected via column chromatography to give 11 as an oil (1.9 g, 86%): IR 1005, 1048, 1094, 1253, 1360, 1462, 2855, 2928 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 0.02 (s, 6 H), 0.86 (s, 9 H), 1.28–1.50 (m, 20 H), 2.11 (t, 2 H, J = 2.3 Hz ), 2.90 (br, 4 H), 3.57 (t, 2 H, J = 6.6 Hz), 5.47 (t, 2 H, J = 4.5 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 0.04, 17.1, 18.3, 18.8, 25.7, 25.9, 28.8, 28.9, 29.0, 32.8, 63.2, 77.6, 80.4, 126.5.

(Z)-Docos-11-en-8,14-diynedial (15)

To a stirred solution of 11 (1.3 g, 2.3 mmol) in THF (21 mL) at 0 °C was added TBAF (9.23 mL, 9.23 mmol). The mixture was stirred at this temperature for 10 minutes then warmed to room temperature and stirred for 2 h. The reaction mixture was then filtered on a silica gel pad and washed with 80% EtOAc/hexanes. The filtrate was concentrated under high vacuum and the crude material was purified via column chromatography to afford the diol as a yellow solid (694 mg, 87%); mp 38–39 °C: IR 1057, 1096, 1255, 1462, 2855, 2929, 3339 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 1.28–1.54 (m, 20 H), 2.09–2.13 (m, 4 H), 2.89 (br, 4 H), 3.60 (t, 4 H, J = 6.7 Hz), 5.45 (t, 2 H, J = 4.5 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 17.2, 18.7, 25.6, 28.8, 28.9, 29.0, 32.7, 62.9, 77.7, 80.4, 126.5.

The diol (690 mg, 1.77 mmol) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (2 mL). This mixture was added to a stirred suspension consisting of PCC (1.2 g, 5.32 mmol) and celite (1.2 g) in CH2Cl2 (15 mL) under N2. After 2 h the starting material disappeared and the mixture was diluted with Et2O then filtered through a pad of celite. This was thoroughly rinsed with Et2O followed by solvent removal under reduced pressure to afford 15 as an oil (634 mg, 92%): IR 1464, 1724, 2857, 2932 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 1.35–1.67 (m, 16 H), 2.12 (t, 4 H, J = 2.1 Hz), 2.39 (dt, 4 H, J = 7.2, 1.5 Hz), 2.89 (br, 4 H), 5.45 (t, 2 H, J = 4.5 Hz), 9.73 (2 H, t, J = 1.8 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 17.2, 18.7, 21.7, 21.9, 28.5, 28.6, 43.8, 77.8, 80.2, 126.5, 202.8; HRMS calcd for C22H32O2 (M+Na) 351.2300, found 351.2297.

(2E, 13Z, 24E)-Hexacosa-2,13,24-trien-10,16-diynedial

To a stirred solution of the dialdehyde 15 (568 mg, 1.5 mmol) in benzene (15 mL) was added Ph3PCHCHO (1.8 g, 6 mmol) under N2. The reaction mixture was refluxed in an oil bath until complete consumption of the starting material (TLC/1H NMR). This was then filtered over silica gel, concentrated, then purified via column chromatography to give the dienedialdehyde as an oil (510 mg, 79%): IR 1124, 1461, 1690, 2857, 2931 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 1.32–1.51 (m, 16 H), 2.12 (t, 4 H, J = 2.1 Hz), 2.32 (dt, 4 H, J = 7.2, 1.5 Hz), 2.89 (br, 4 H), 5.45 (t, 2 H, J = 4.5 Hz), 6.10 (dd, 2 H, J = 15.6, 7.9 Hz), 6.83 (dt, 2 H, J = 15.6, 6.8 Hz), 9.48 (d, 2 H, J = 7.9 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 17.2, 18.7, 27.7, 28.6, 28.8, 32.6, 43.8, 77.7, 80.2, 126.5, 133.0, 158.8, 194.1.

(4E, 15Z, 26E)-Triaconta-4,15,26-trien-1,12,18,29-tetrayne-3,28-diol (1)

To a stirred solution of ethynylmagnesium bromide (6.2 mL, 3.06 mmol) in THF (11 mL) at 0 °C under N2, was added the dienedialdehyde (490 mg, 1.1 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at this temperature for 2 h then quenched by the addition of saturated NH4Cl solution. The aqueous layer was thoroughly extracted using EtOAc. The organics were combined, dried (MgSO4) and purified via column chromatography to afford 1 as a solid (480 mg, 92%); mp 33–42°C: IR 736, 970, 1282, 1433, 1661, 2856, 2920, 3298, 3355 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 1.28–1.45 (m, 16 H), 2.03 (br, 2 H) 2.05–2.11 (m, 8 H), 2.54 (d, 2 H, J = 2.1 Hz), 2.90 (t, 4 H, J = 2.4 Hz ), 4.80 (br, 2 H), 5.45 (t, 2 H, J = 4.4 Hz), 5.58 (dd, 2 H, J = 15.3, 6.1 Hz), 5.88 (dt, 2 H, J = 14.3, 6.6 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 17.2, 18.7, 28.6, 28.7, 28.8, 28.9, 31.9, 62.8, 74.0, 77.7, 80.4, 83.4, 126.5, 128.5, 134.0; HRMS calcd for C30H40O2 (M+Na) 455.2926, found 455.2914.

Enzymatic resolution of (1)

A flask was charged with lipase AK Amano “20” (960 mg) molecular sieves (960 mg) vinyl acetate (1.6 mL, 17 mmol) hexanes (12 mL ) and the racemic diol (480 mg, 1.12 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for several hours. Reaction progress was monitored by TLC and 1H NMR. When the amount of the diacetate was about the same as the amount of the diol and half the amount of the monoacetate the reaction was stopped. The reaction mixture was filtered over a pad of silica then purified via column chromatography to give (−)-1 as a viscous oil (99 mg, 21%); [α]D −40.4 (c 0.04,, CHCl3): IR 737, 970, 1283, 1433, 1663, 2856, 2930, 3290, 3355; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 1.30–1.48 (m, 16 H), 1.85 (br, 2 H) 2.04 (t, 4 H, J = 7.1 Hz) 2.11–2.12 (m, 4 H), 2.54 (d, 2 H, J = 2.4 Hz), 2.90 (br, 4 H), 4.81 (t, 2 H, J = 5.1 Hz), 5.46 (t, 2 H, J = 4.7 Hz), 5.61 (dd, 2 H, J = 15.2, 6.4 Hz), 5.87 (dt, 2 H, J = 15.1, 6.7 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 17.2, 18.7, 28.6, 28.7, 28.8, 28.9, 31.8, 62.7, 73.9, 77.7, 80.4, 83.3, 126.5, 128.4, 134.4; HRMS calcd for C30H40O2 (M+Na) 455.2926, found 455.2914.

The monoacetate 17 was obtained as an oil (248 mg, 46%); [α]D +12.4 (c 0.12, CHCl3); IR 732, 911, 1015, 1228, 1370, 1739, 2856, 2930, 3291, 3449 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 1.27–1.48 (m, 16 H), 2.04–2.08 (m, 4 H), 2.10 (s, 3 H), 2.11–2.12 (m, 4 H), 2.54 (d, 2H, J = 2.1 Hz ), 2.89 (br, 4H), 4.81 (brd, 2 H, J = 5.1 Hz), 5.45 (t, 2 H, J = 4.5 Hz), 5.51 (dd, 1 H, J = 15.3, 6.5 Hz), 5.57 (dd, 1 H, J = 15.1, 6.1 Hz), 5.79 (d, 1 H, J = 6.3 Hz) 5.87 (dt, 2 H, J = 15.3, 6.1 Hz), 5.97 (dt, 2 H, J = 15.3, 6.5 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ17.2, 18.7, 21.0, 24.8, 28.5, 28.6, 28.7, 28.9, 31.8, 31.9, 34.5, 62.7, 63.7, 64.1, 72.8, 73.9, 74.7, 77.7, 79.8, 80.4, 124.4, 126.5, 128.4, 134.4,137.0, 169.7; HRMS calcd for C32H42O3 (M+Na) 497.3032, found 497.3025.

The diacetate 16 was obtained as an oil (92 mg, 20%); [α]D +22.9 (c 0.04, CHCl3 ): IR 969, 1015, 1228, 1370, 1433, 1741, 2857, 2931, 3290 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 1.29–1.45 (m, 16 H), 2.04–2.07 (m, 4 H), 2.10 (s, 6 H), 2.11 (t, 4 H, J = 4.6 Hz), 2.54 (d, 2 H, J = 2.1 Hz ), 2.90 (br, 4 H), 5.45 (t, 2 H, J = 4.5 Hz), 5.51 (dd, 2 H, J = 15.2, 6.4 Hz), 5.80 (d, 2 H, J = 6.0 Hz), 5.98 (dt, 2 H, J = 15.3, 6.5 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 18.7, 20.9, 24.0, 28.6, 28.7, 28.9, 31.8, 34.5, 64.1, 74.7, 77.7, 79.9, 80.4, 124.4, 126.5, 137.0, 169.7; HRMS calcd for C34H44O4 (M+Na) 539.3137, found 539.3115.

(3 S, 28S)-Triaconta-1,12,18,29-tetrayn-4E,15Z,26E-trien-3,28-diol (+)-1

The diacetate (60 mg, 0.11 mmol) and K2CO3 (6 mg, 0.04 mmol) were dissolved in MeOH (2 mL) with stirring under N2. The reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature for several hours until the complete consumption of the starting material, the reaction mixture was then quenched using 1N HCl and the organic layer was extracted with EtOAc. Purification was effected using column chromatography to give (+)-1 as a viscous oil (45 mg, 96%); [α]D +41.3 (c 0.03, CHCl3): IR 736, 970, 1283, 1433, 1663, 2856, 2930, 3290, 3355 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 1.30–1.48 (m, 16 H), 1.85 (br, 2 H) 2.06 (t, 4 H, J = 6.4 Hz) 2.12 (t, 4 H, J = 2.3 Hz ), 2.54 (d, 2 H, J = 2.1 Hz), 2.90 (br, 4 H), 4.81 (t, 2 H, J = 5.1 Hz), 5.46 (t, 2 H, J = 4.5 Hz), 5.61 (dd, 2 H, J = 15.2, 6.4 Hz), 5.87 (dt, 2 H, J = 15.1, 6.7 Hz); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C) δ 17.2, 18.7, 28.6, 28.7, 28.8, 28.9, 31.8, 62.7, 73.9, 77.7, 80.4, 83.3, 126.5, 128.4, 134.4; HRMS calcd for C30H40O2 (M+Na) 455.2926, found 455.2914.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Anti cancer C30 polyacetylenic alcohols, dideoxypetrosynol A (1), duryne (2), and petrosynol (3). Compound 1 contains a central (Z)-enedipropargyl moiety, also known as a “skipped” enediyne.

Table.

Absolute configurations of naturally occurring C2-symmetric acetylenic alcohols

| Name | Chain length | [α]D | Configuration | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adociacetylene | 30 | +21.7 | S,S | Adocia sp. |

| Petrosynol | 30 | +107 | S,S | Petrocia sp. |

| C20 alkynol | 20 | +26 | S,S | Callyspongia pseudoreticulata |

| Duryne | 30 | +29 | S,S | Cribrochalina dura |

| Dideoxypetro-synol A (1) | 30 | +41.3 | S,S | Petrocia sp. |

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Institutes of Health (GM069441) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Professors James Marshall and Hans Reich for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.eurjoc.org/ or from the author.

Supporting Information (see footnote on the first page of this article): 1H and 13C NMR, and HRMS spectra for compounds 1, 9, 11, 13–17.

References

- 1.Kim JS, Im KS, Jung JH, Kim YL, Kim J, Shim CJ, Lee CO. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:3151. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright AE, McConnell OJ, Kohmoto S, Lui MS, Thompson W, Snader KM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:1377. doi: 10.1021/np50050a064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isaacs S, Kashman Y, Loya S, Hizi A, Loya Y. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:10435. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fusetani N, Shiragaki T, Matsunaga S, Hashimoto K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:4313. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dembitsky VM. Lipids. 2006;41:883. doi: 10.1007/s11745-006-5044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss RB. Seminars In Oncology. 1992;19:670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim DK, Lee MY, Lee HS, Lee DS, Lee JR, Lee BJ, Jung JH. Cancer Letters. 2002;185:95. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gung BW, Omollo AO. J Org Chem. 2008;73:1067. doi: 10.1021/jo702399j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gleiter R, Merger R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:1845. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller P, Rodriguez D. Helv Chim Acta. 1985;68:975. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taber DF, Zhang Z. J Org Chem. 2005;70:8093. doi: 10.1021/jo0512094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaudin JM, Morel C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:5749. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poulain S, Noiret N, Patin H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:7703. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capon RJ, Skene C, Liu EH, Lacey E, Gill JH, Heiland K, Friedel T. J Org Chem. 2001;66:7765. doi: 10.1021/jo0106750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bettencourt AP, Freitas AM, Montenegro MI, Nielsen MF, Utley JHP. J Chem Soc-Perkin Trans. 1998;2:515. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall JA, Lebreton J. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:2925. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall JA, Jenson TM, Dehoff BS. J Org Chem. 1987;52:3860. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oestreich M, Frohlich R, Hoppe D. J Org Chem. 1999;64:8616. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bordwell FG. Accounts Chem Res. 1988;21:456. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reich HJ, Holladay JE, Walker TG, Thompson JL. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:9769. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson MS, Polak ML, Bierbaum VM, Depuy CH, Lineberger WC. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:6766. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanko R, Hammond MD, Fruchtmann R, Pfitzner J, Place GA. J Med Chem. 1990;33:1163. doi: 10.1021/jm00166a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gung BW, Dickson H, Shockley S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:4761. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brummond KM, McCabe JM. Synlett. 2005:2457. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Appel R. Angew Chem-Int Edit Engl. 1975;14:801. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dawson MI, Vasser M. J Org Chem. 1977;42:2783. doi: 10.1021/jo00436a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burgess K, Jennings LD. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:6129. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgess K, Jennings LD. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:7434. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gung BW, Dickson HD, Seggerson S, Bluhm K. Synth Commun. 2002;32:2733. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.