Abstract

Background

Apolipoprotein B100 (ApoB100) determination is superior to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) to establish cardiovascular (CV) risk, and does not require prior fasting. ApoB100 is rarely measured alongside standard lipids, which precludes comprehensive assessment of dyslipidemia.

Objectives

To evaluate two simple algorithms for apoB100 as regards their performance, equivalence and discrimination with reference apoB100 laboratory measurement.

Methods

Two apoB100-predicting equations were compared in 87 type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients using the Discriminant ratio (DR). Equation 1: apoB100 = 0.65*non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol + 6.3; and Equation 2: apoB100 = −33.12 + 0.675*LDL-C + 11.95*ln[triglycerides]. The underlying between-subject standard deviation (SDU) was defined as SDU = √ (SD2B - SD2W/2); the within-subject variance (Vw) was calculated for m (2) repeat tests as (Vw) = Σ(xj -xi)2/(m-1)), the within-subject SD (SDw) being its square root; the DR being the ratio SDU/SDW.

Results

All SDu, SDw and DR’s values were nearly similar, and the observed differences in discriminatory power between all three determinations, i.e. measured and calculated apoB100 levels, did not reach statistical significance. Measured Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficients between all apoB100 determinations were very high, respectively at 0.94 (measured vs. equation 1); 0.92 (measured vs. equation 2); and 0.97 (equation 1 vs. equation 2), each measurement reaching unity after adjustment for attenuation.

Conclusion

Both apoB100 algorithms showed biometrical equivalence, and were as effective in estimating apoB100 from routine lipids. Their use should contribute to better characterize residual cardiometabolic risk linked to the number of atherogenic particles, when direct apoB100 determination is not available.

Keywords: ApoB100, LDL-C, Non-HDL-C, Discriminant ratio, Type 2 diabetes, Cardiovascular risk

Introduction

Low-density lipoproteins (LDL) and their very-low density lipoprotein (VLDL) precursors represent the major atherogenic particles. Each contains a single apolipoprotein B100 (apoB100) molecule, which ensures the structural integrity of the lipoprotein, and binds to the hepatic receptor for catabolic removal of LDL. The “small-dense” LDL phenotype confers a higher cardiovascular (CV) risk than that resulting from their cholesterol load. Therefore circulating apoB100 level more accurately reflects the number of atherogenic particles, 90% of apoB100 belonging to LDL irrespective of their size. The determination of apoB100 does not require prior fasting, unlike estimation of LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) by Friedewald’s formula [1-8].

Numerous studies have demonstrated the superiority of apoB100 relative to LDL-C to establish CV risk, and improvement of outcomes after lipid-lowering drug (LLD) therapy [2-6,9]. The Adult Treatment Panel III proposed that in individuals with elevated triglycerides (TG), non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C) should be treated as secondary therapy goal, after targeting LDL-C; moreover non-HDL-C appears a better predictor of CV risk than LDL-C, especially in statin-treated patients [2,6]. However, the relationships between LDL-C, non-HDL-C and apoB100 are often less convergent than expected, and therefore less predictable in patients at high cardiometabolic risk, including those with high TG and/or the metabolic syndrome. In these patients, including those with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), non-HDL-C and apoB100 are therefore less interchangeable than the reading of the general recommendations for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia would suggest.

In the absence of consensual guidelines, the current recommendation for hypercholesterolemic patients at high cardiometabolic risk is to bring at target three key modifiable variables: (i) LDL-C; (ii) non-HDL-C; and (iii) apoB100[6,10]. In real life however, apoB100 determination is rarely performed alongside routine lipids, which precludes such comprehensive assessment of residual dyslipidemia. Consequently, simple algorithms were proposed to estimate apoB100 level from routine lipids, based on LDL-C and non-HDL-C as freely-available biometrical equivalent to apoB100[7,8].

The aim of this study was to compare the performance and true equivalence of two apoB100-predicting algorithms in T2DM patients considered at high cardiometabolic risk, with reference to laboratory determination of apoB100 and against each other. We used the Discriminant Ratio (DR) methodology, which standardises comparisons between measurements by taking into account fundamental properties for assessing imprecision and practical performance of tests designed to quantify similar variables [7,11-14]. Cross-validation of these algorithms should prompt potential users to increasingly rely on them, to derive unbiased apoB100 values from landmark epidemiological or interventional databases, or from current standard lipids in specific situations where it is desirable to know the levels of non-HDL-C and that of apoB100.

Methods and statistical analysis

We studied 87 consecutive (84% white Caucasians; 6% North-Africans; 5% sub-Saharan Africans) patients with T2DM, treated or not with lipid-lowering drug(s) (LLD). All lipid values were obtained in the fasting state, on two non-consecutive days. The time-span between sampling, obtained during regular outpatients’ follow-up visits, was 2–6 months. The following biologic variables were recorded: glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting lipids (total cholesterol [C], HDL-C, and TG). Fasting duration was ≥10-hours, with last intake of food allowed at dinner the day before sampling. No change in LLD(s) was allowed during the interval that separated the two days of sampling.

Total C and TG were determined using the SYNCHRON system (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA). HDL-C was determined with the ULTRA-N-geneous reagent (Genzyme Corporation, Cambridge, MA). ApoB100 was measured with immunonephelometry on BNII Analyzer (Siemens Healthcare Products GmbH, Marburg, Germany) from the same blood samples destined for routine lipids determination. The within-subject coefficients of variation were as follows: 5.4% [total C]; 7.1% [HDL-C]; and 6.9% [apoB100]. LDL-C was computed with Friedewald’s formula [1]; non-HDL-C by subtracting HDL-C from total C.

Besides direct measurement, ApoB100 level was calculated from routine lipids using the two following equations:

| (1) |

based on fasting or nonfasting lipids [ref. 7]

| (2) |

based on fasting lipids only [ref. 8]

The presence of atherogenic dyslipidemia (AD) was defined as the combined occurrence of decreased HDL-C (<40 [males] or <50 mg/dL [females]) plus elevated fasting TG (≥150 mg/dL) using baseline lipid values (ie, before any LLD(s) in treated patients) [15]. Glomerular filtration rate was estimated using the Modified Diet in Renal Disease formula [16].

The Discriminant Ratio (DR) methodology compares different tests measuring the same underlying physiological variable by determining the ability of a test to discriminate between different subjects, and the comparison of discrimination between different tests as well as the underlying correlation between pairs of tests adjusting for the attenuating effect of within-subject variation [7,11-14]. In a comparison study where duplicates measurements are performed in each subject, the measured between-subject standard deviation (SDB) is calculated as the SD of the subject mean values calculated from the 2 replicates.

•The standard mathematical adjustment to yield the underlying between-subject SD (SDU) is: SDU = √ (SD2B - SD2W/2);

•The within-subject variance (Vw) is calculated for m repeat tests as (Vw) = Σ(xj -xi)2/(m-1)), the within-subject SD (SDw) being its square root;

•The DR represents the ratio SDU/SDW

Confidence limits for DR’s and the testing for equivalence of different DR’s were calculated and differences were considered significant for p < 0.05. Given sample size and number of replicates, the minimal detectable significant difference in DR for the present study was 0.42. Coefficients of correlation between pairs of tests used to estimate apoB100 (measured vs. estimated) were adjusted to include an estimate of the underlying correlation, as standard coefficients tend to underestimate the true correlation between tests, due to within-subject variation [13].

The study was performed in accordance with the institutional review board of St-Luc Academic Hospital.

Results

The patients’ characteristics are described in Table 1. Mean age (1 SD) was 65 (10) years, with a male gender predominance. Mean body mass index was in the overweight/obese range, and patients had long-standing diabetes (mean duration 15 (8) years), and high prevalence of metabolic syndrome or of its defining nonglycaemic features, as well as macroangiopathies (coronary [25%] and peripheral [11%] artery disease and/or cerebrovascular disease [5%]). LLDs were widely prescribed, mostly as statins (74%) and/or fibrates (43%). Mean glycaemic control, as reflected by HbA1c, was suboptimal at 62 (11) mmol/mol. The current lipid profile was typical of that of patients with the usual form of T2DM, i.e. associated with features of the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance: low HDL-C, raised non-HDL-C, apoB100, TG, and high frequency (49%) of AD.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

|

n |

|

87 |

|

age |

years |

65 (10) |

|

diabetes duration |

years |

15 (8) |

|

male : female |

% |

75 : 25 |

|

smoking§ |

|

38-47-15 |

|

body mass index |

kg.m-2 |

29.3 (5.9) |

|

waist circumference |

cm |

104 (15) |

|

metabolic syndrome |

% |

87 |

|

hypertension |

% |

91 |

|

anti-dyslipidemic drug(s) |

% |

90 |

|

statin-fibrate-ezetimibe |

% |

74-43-2 |

|

HbA1c |

mmol.mol-1 |

62 (11) |

|

glomerular filtration rate |

mL.min-11.73m2 |

80 (32) |

|

albuminuria |

μg.mg creatinine-1 |

67 (126) |

|

total cholesterol |

mg.dL-1 |

161 (35) |

|

LDL-cholesterol |

mg.dL-1 |

80 (30) |

|

non-HDL-cholesterol |

mg.dL-1 |

113 (36) |

|

HDL-cholesterol |

mg.dL-1 |

49 (15) |

|

apoB100 |

mg.dL-1 |

81 (23) |

| estimated apoB100 (equation 1)* |

mg.dL-1 |

80 (23) |

| estimated apoB100 (equation 2)** |

mg.dL-1 |

80 (22) |

|

triglycerides |

mg.dL-1 |

169 (105) |

|

atherogenic dyslipidemia |

% |

49 |

|

coronary artery disease |

% |

25 |

|

peripheral artery disease |

% |

11 |

| transient ischemic attack/stroke | % | 5 |

Results are expressed as means (1 standard deviation) or proportions; apo, apolipoprotein; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; §: never-former-current; * : equation 1: apoB100(mg/dL) = [0.65 × non - HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL)] + 6.3 (mg/dL); * *: equation 2: apoB100(mg/dL) = − 33.12 (mg/dL) + [0.675 × LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL)] + [11.95 × ln[triglycerides] (mg/dL)].

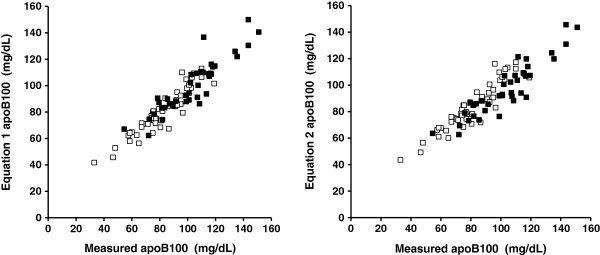

Figure 1 illustrates the plots of untransformed values of measured apoB100 vs. estimated apoB100 from equations 1 and 2, the values representing the means of the two estimates obtained on different days. The linear regression formula for equation 1 was: calculated apoB100 = 0.871 × measured apoB100 + 9.64 mg/dL (R2 = 0.8756); whereas that of equation 2 was: calculated apoB100 = 0.812 x measured apoB100 + 16.0 mg/dL (R2 = 0.8451). The figure also shows the homoscedastic behaviour on repeat testing of the data spread. The alignment of the regression lines was not affected by mean baseline TG levels obtained on day 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Plots of untransformed values of measured apolipoprotein B100(apoB100; X axis) vs. estimated apoB100from equation 1(Y axis; left panel) and equation 2 (Y axis; right panel) in n =87 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Equation 1: apoB100 (mg/dL) = [0.65 x non-high - density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL)] + 6.3 (mg/dL). Equation 2: apoB100 (mg/dL) = − 33.12 (mg/dL) + [0.675 x low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL)] + [11.95 x ln [triglycerides] (mg/dL)]. All values obtained from the means of different estimates performed on separate days. The open squares represent patients with mean fasting triglycerides (TG) <150 mg/dL; the solid squares represent patients with elevated fasting TG (150 - 400 mg/dL).

The precision and discrimination of the three apoB100 estimates, expressed as underlying between-subject Standard Deviation (SDu), global within-subject Standard Deviation (SDw), and Discriminant Ratio (DR) are shown in Table 2. All SDu, SDw and DR’s values were almost similar, and the observed differences in discriminatory power between all three determinations did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Precision and discrimination of three apoB100estimates, expressed as underlying between-subject Standard Deviation (SDu), global within subject Standard Deviation (SDw), and Discriminant Ratio (DR)

| SDu | SDw | DR | Cls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

measured apoB100 (mg/dL) |

17.8 |

19.9 |

0.90 |

0.63-1.19 |

|

equation 1:apoB100(mg/dL) = [0. 65 × non − HDL − C (mg/dL)] + 6. 3 (mg/dL) |

15.8 |

19.7 |

0.80 |

0.53-1.10 |

| equation 2:apoB100 (mg/dL) = − 33. 12 (mg/dL) + [0. 675 × LDL − C (mg/dL) + [11. 95 × ln[TG] (mg/dL)] | 14.5 | 19.4 | 0.75 | 0.47-1.04 |

Values from results of individual tests and means of their duplicates in 87 patients with type 2 diabetes. Confidence intervals [Cls] for DR’s [2.5-97.5%] in square brackets. apo, apolipoprotein; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TG, triglycerides. All differences between DR’s were non significant (p > 0.05).

The measured Pearson’s product–moment correlation coefficients between the three apoB100 determinations methods were very high, respectively 0.94 (measured vs. equation 1 apoB100); 0.92 (measured vs. equation 2 apoB100); and 0.97 (equation 1 vs. equation 2 apoB100), each reaching unity (1.00) once values were correlated after adjustment for attenuation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Measured pearson correlation coefficients between measured and estimated apoB100levels with values adjusted for attenuation (between brackets)

| equation 1 apoB100* | equation 2 apoB100** | |

|---|---|---|

|

measured apoB100 |

0.94 [1.00] |

0.92 [1.00] |

| equation 1 apoB100* | 0.97 [1.00] |

All correlations were calculated from means of values of tests duplicates in n = 87 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. apo, apolipoprotein; * equation 1: apoB100 (mg/dL) = [0.65 × non-high - density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL)] + 6.3 (mg/dL); ** equation 2: apoB100(mg/dL) = − 33.12 (mg/dL) + [0.675 × low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL)] + [11.95 × ln[triglycerides] (mg/dL)]. For correlation between estimates, values were obtained from the mean of different estimated performed on separate days.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that in patients with T2DM, two simple equations published to date were as effective to calculate apoB100 concentration from routine lipids [7,8]. In addition, as the underlying correlation between apoB100 levels estimated by the two formulas reached unity, once preanalytical and analytical attenuation was taken into account, these two algorithms may be used interchangeably to assess an equivalent underlying biological variable. Even though the two algorithms were developed from lipid values obtained in different populations and conditions, each formula can substitute for each other, being as precise and interchangeable.

Although equation 1 was computed using lipid values from a small cohort (n = 45) of Caucasian T2DM patients, and equation 2 used fasting lipids from an extensive cohort (n = 73047) of healthy Koreans representative of a general Asian population, the two means of estimating apoB100 were perfectly correlated, and as effective and precise. This illustrates the performance of the comparison of measurements methods based on the DR methodology, which requires only limited samples (n ≥20 for 2 replicates), as long as the sample represents a meaningful clinical range for the variable under study [see appendix of [13] for a detailed discussion on sample size requirements for estimating DRs].

ApoB100 metabolism and physiology are comparable in diabetic and nondiabetic subjects, as well as in different ethnic groups. The equations appear applicable across the two major ethnic groups that provided the source data, and uninfluenced by baseline TG values. An inherent advantage of equation 1 is the inclusion of lipid values that do not require sampling in the fasting state, whereas equation 2 requires a fasting lipid panel [7,8]. Another limitation of equation 2, in terms of routine clinical practice, is that LDL-C is usually calculated from Friedewald’s formula, which induces systematic and linear underestimation once fasting TG rise above 200 mg/dl, confining the applicability of equation 2 to patients with fasting TG <400 mg/dL, unless direct LDL-C measurement is available [2].

For use in equation 1, non-HDL-C offers the added advantage of being derived from the compute of two robust, well-established measurements methods, namely total cholesterol and HDL-C [7]. Although Cho et al. used direct, and hence more expensive measurements of LDL-C, contributing to enhance accuracy of their algorithm [8], there is an intrinsic rationale to opt for equation 1 in populations with high prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia, such as patients with AD [6,10,15,17-19]. They belong to the highest cardiometabolic risk category, for which it is recommended to assess (and bring to target), both non-HDL-C and apoB100, on top of LDL-C [6,10,20].

There is still no consensus among the various players on the ultimate relevance to measure apoB100, non-HDL-C, or both, for baseline or residual CV risk classification, One might wonder what is the advantage of being able to dispose of apoB100 from an equation that incorporates non-HDL-C, since the latter is considered by ATPIII as adequate and sufficient. Notwithstanding the ongoing debate, the apoB100 concept is intrinsically easier to apprehend than non-HDL-C, which contains in itself a ferment of educational failure because it represents a state of otherness defined by a non-number, instead of a single atherogenic lipid variable [21].

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the biometrical equivalence of two original apoB100 algorithms, which are as effective in estimating the concentration of apoB100 from routine lipids, and may be used interchangeably. One approach requires fasting blood lipids, while the other is not influenced by fasting status, and therefore independent of food intake prior to sampling. These algorithms should contribute to better characterize residual cardiometabolic risk linked to the number of atherogenic particles in patients with available standard lipids, but in whom apoB100 assay was not performed for various reasons. The practical implications of these findings are directly relevant to routine clinical practice.

Competing interests

No competing or conflicting interests regarding its content, including with industry.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Michel P Hermans, Email: michel.hermans@diab.ucl.ac.be.

Sylvie A Ahn, Email: michel.rousseau@uclouvain.be.

Michel F Rousseau, Email: rousseau@card.ucl.ac.be.

References

- Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Final Report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sniderman AD. Non-HDL cholesterol versus apolipoprotein B in diabetic dyslipoproteinemia. Alternatives and surrogates versus the real thing. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2207–2208. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.7.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denke MA. Weighing in before the fight. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol versus Apolipoprotein B as the best predictor for coronary heart disease and the best measure of therapy. Circulation. 2005;112:3368–3370. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sniderman AD. Apolipoprotein B versus non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. And the winner is…. Circulation. 2005;112:3366–3367. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunzell JD, Davidson M, Furberg CD, Goldberg RB, Howard BV, Stein JH, Witztum JL. American Diabetes Association; American College of Cardiology Foundation. Lipoprotein management in patients with cardiometabolic risk. Consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:811–822. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans MP, Sacks FM, Ahn SA, Rousseau MF. Non-HDL-cholesterol as valid surrogate to apolipoprotein B100 measurement in diabetes: Discriminant Ratio and unbiased equivalence. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho DS, Woo S, Kim S, Byrne CD, Sung KC, Kong JH. Estimation of plasma apolipoprotein B concentration using routinely measured lipid biochemical tests in apparently healthy Asian adults. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012;18:55. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-11-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genest J, McPherson R, Frohlich J, Anderson T, Campbell N, Carpentier A, Couture P, Dufour R, Fodor G, Francis GA, Grover S, Gupta M, Hegele RA, Lau DC, Leiter L, Lewis GF, Lonn E, Mancini GB, Ng D, Pearson GJ, Sniderman A, Stone JA, Ur E. Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult – 2009 recommendations. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:567–579. doi: 10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70715-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querton L, Buysschaert M, Hermans MP. Hypertriglyceridemia and residual dyslipidemia in statin-treated, patients with diabetes at the highest risk for cardiovascular disease and achieving very-low low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels. J Clin Lipidol. 2012. published online 16 April 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hermans MP, Levy JC, Morris RJ, Turner RC. Comparison of tests of beta-cell function across a range of glucose tolerance from normal to diabetes. Diabetes. 1999;48:1779–86. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.9.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans MP, Levy JC, Morris RJ, Turner RC. Comparison of insulin sensitivity tests across a range of glucose tolerance form normal to diabetes. Diabetologia. 1999;42:678–87. doi: 10.1007/s001250051215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy JC, Morris RJ, Hammersley M, Turner RC. Discrimination, adjusted correlation, and equivalence of imprecise tests: application to glucose tolerance. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:E365–75. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.2.E365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans MP, Ahn SA, Rousseau MF. The non-HDL-C/HDL-C ratio provides cardiovascular risk stratification similar to the ApoB/ApoA1 ratio in diabetics: Comparison with reference lipid markers. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2007;1:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2006.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans MP, Ahn SA, Rousseau MF. Log(TG)/HDL-C is related to both residual cardiometabolic risk and β-cell function loss in type 2 diabetes males. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2010;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans MP, Fruchart JC. Reducing residual vascular risk in patients with atherogenic dyslipidaemia: where do we go from here? Clin Lipidol. 2010;5:811–26. doi: 10.2217/clp.10.65. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans MP, Ahn SA, Rousseau MF. In: Recent Advances in the Pathogenesis, Prevention and Management of Type 2 Diabetes and its Complications. Mark B, editor. Croatia: Zimering, Intech, Rijeka; 2011. Residual vascular risk in T2DM: the next frontier; pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans MP, Fruchart JC. Reducing vascular events risk in patients with dyslipidaemia: an update for clinicians. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2011;2:307–323. doi: 10.1177/2040622311413952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wägner AM, Pérez A, Zapico E, Ordóñez-Llanos J. Non-HDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein B in the dyslipidemic classification of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2048–51. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.7.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson TA. Opening a new lipid “apo-thecary”: incorporating apolipoproteins as potential risk factors and treatment targets to reduce cardiovascular risk. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:762–80. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]