Abstract

Objective

The brain foreign body response (FBR) is an important process that limits the functionality of electrodes that comprise the brain-machine interface. Associated events in this process include leakage of the blood brain barrier (BBB), reactive astrogliosis, recruitment and activation of microglia, and neuronal degeneration. Proper BBB function is also integral to maintaining neuronal health and function. Previous attempts to characterize BBB integrity have shown homogeneous leakage of macromolecules up to 10 nm in size. In the present study, we describe a new method of measuring BBB permeability during the foreign body response in a mouse model.

Approach

Fluorescent nanoparticles were delivered via the tail vein into implant-bearing mice. Tissue sections were then analyzed using fluorescence microscopy to observe nanoparticles in the tissue. Gold nanoparticles were also used in conjunction with TEM to confirm the presence of nanoparticles in the brain parenchyma.

Main results

By using polymer nanoparticle tracers, which are significantly larger than conventional macromolecular tracers, we show near-implant BBB gaps of up to 500 nm in size that persist for at least 4 weeks after implantation. Further characterization of the BBB illustrates that leakage during the brain FBR is heterogeneous with gaps between at least 10 and 500 nm. Moreover, electron microscopy was used to confirm that the nanoparticle tracers enter into the brain parenchyma near chronic brain implants.

Significance

Taken together, our findings demonstrate that the FBR-induced BBB leakage is characterized by larger gaps and is of longer duration than previously thought. This technique can be applied to examine the BBB in other disease states as well as during induced, transient, BBB opening.

1. Introduction

Development of neural interfacing technologies has the potential to aid in the communication, mobility, and monitoring of individuals whose function is limited by physical injury or progressive disease (1). A functioning neural interface requires an electrode to record and/or stimulate neurons, a processing step to decode the signals, and a method of output like a robotic limb or electrical stimulus (2, 3). Examples of currently used devices include cochlear implants (3, 4), visual prosthetics (5, 6), and prosthetic limbs (7). When properly utilized, the technology could also aid in the management of epilepsy and neurodegenerative diseases.

While there are many challenges in designing a functional neural interface, one limitation to its long-term viability is the foreign body response induced by the presence of the electrode (8). The foreign body response is distinct from injury-induced inflammation because it develops in response to the chronic presence of the implant. Documented differences between the response to an implant stab wound, where no implant is left in the brain, and to an implant in the brain highlight this distinction (9). Moreover, the brain FBR is distinguished by the hyperproliferation and hypertrophy of reactive astrocytes to form a glial scar, the activation and recruitment of microglia, and neuronal degradation (9-12). Glial scarring prevents the direct contact between neurons and electrodes leading to suboptimal recordings (13, 14). In addition, loss of healthy neurons from the area around the electrode is problematic, since they are essential for proper recording.

Recently, we and others have shown that the brain FBR is associated with prolonged leakage of the blood brain barrier (BBB) (11, 12, 15-17). Specifically, studies have shown that unlike the resolution of BBB leakage following a stab wound, implantation of biomaterials induced leakage that lasted for up to 4 wk (11). Thus, the brain FBR presents additional complications that could hinder the performance and longevity of intracranial implants.

As a multi-component complex, the BBB serves as a physical, transport, and metabolic barrier in order to protect the neural microenvironment (18). Disruption of the BBB in the vicinity of intracranial implants could contribute to overall inflammation and death of neurons (11). At the molecular level, BBB leakage was correlated with the loss of proteins zona occludens 1, and 2, which suggests destabilization of tight junctions in brain endothelial cells (11). Moreover, mice with increased levels of matrix metalloproteinases displayed disruption of the basement membrane that supports blood vessels, which was associated with excessive and prolonged leakage of the BBB (15). Thus, it is postulated that the FBR interferes with the physical integrity of the BBB. However, it is possible that transport and/or metabolic barrier function are also affected (19).

Disruption of the BBB plays a role in many disease states because it serves to regulate the transport of molecules from the blood into the brain, which depends on the size, lipid solubility, and charge (20). In the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, this limitation forces the use of a prodrug, L-DOPA, in order to enhance delivery of dopamine to the brain. The BBB can be acutely and transiently opened by infusing a hyperosmolar solution of mannitol, or using a combination of ultrasound and vascularly delivered microbubbles. This approach can be used in short term experiments to deliver larger particles like cells or viruses (21, 22), and the degree of disruption can be monitored by PET or MRI (23-25). MRI and PET imaging methods are limited by their resolution, which does not allow observation of individual tracers or small BBB gaps. For chronic disease states, or areas of limited leakage, small molecular weight tracers are typically used to indicate a compromised BBB.

Barrier function is a highly relevant issue in electrode implantation because it is responsible for limiting the exposure of neurons to macromolecules such as IgG or serum albumin that can induce apoptosis (26-28). Therefore, it is standard approach to evaluate the integrity of the BBB by intravenous delivery of small molecular weight tracers (e.g. Evans blue, dextrans) or immunohistochemical detection of macromolecules that are normally excluded from the brain parenchyma by an intact BBB (29-33). These tracers can be imaged in perfused brain tissue and their detection indicates a leaky BBB. One limitation of these methods is that they do not provide information regarding the size of the gaps that are formed due to the loss of tight junctions. For example, albumin has a size near 7 nm (34), which is large enough to suggest that small molecules and small molecular weight drugs could cross the BBB during the FBR. In addition, macromolecules detected by immunohistochemistry could persist long after repair of the BBB, giving the false impression of an impaired BBB.

In the present study, we describe a novel method for measuring BBB integrity during the brain FBR. By using nanoparticulate tracers we were able to better define the size of particles that can enter the brain parenchyma during the FBR. In addition, our ability to evaluate the integrity of the BBB at a higher resolution allowed us to describe for the first time the heterogeneity of FBR-induced leakage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Surgical Procedures

All animal experiments were approved by Yale’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice received cellulose ester implants as described previously (11, 15). Specifically, cellulose ester filters (Millipore) were cut into 2 mm2 triangles and sterilized by autoclaving. Under isofluorane (Baxter Healthcare) anesthesia mouse scalps were shaved and sterilized using alternating solutions of alcohol, betadine, and sterile water. A midline scalp incision was made using a scalpel and the underlying membranes were moved using a sterile cotton swab. A high speed dental drill and bit were used to drill a hole 1 mm lateral to bregma. The dura was punctured and an implant was placed into the cortex using sterile forceps. The scalp was closed with sutures and the mouse was removed to a recovery cage with free access to food and water.

At either 2d, or 1, 2, or 4 weeks, nanoparticle tracers were injected in mice via the tail vein. Polystyrene nanoparticles (Fluospheres, Invitrogen) were purchased with nominal diameters of 20, 100, 200, 500, and 1,000 nm, and separate fluorescent spectra (Table 1). Tail vein injections consisted of either a 200μL solution of a 2% solution of a single size particle (20 or 100 nm), or a 200μL solution with four different sizes (20, 200, 500, and 1000 nm) of nanoparticles each at 0.5%. Animals were transcardially perfused and fixed with PBS and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, JT Baker) 6 hours after the injection of nanoparticles. The brain was carefully removed and post-fixed in 4% PFA before cyroprotection in a 30% sucrose solution (JT Baker). Thin tissue sections (10μm) were made using a cryotome (Cryocut 1800, Reichert Jung) and mounted on glass slides.

Table 1.

Summary of fluorescent nanoparticle tracers. The diameter, excitation and emission wavelengths, and the color of each nanoparticle in the image are listed.

| Size (nm) | Excitation/Emission (nm) | Color |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 580/605 | Red |

| 100 | 580/605 | Red |

| 200 | 660/680 | Yellow |

| 500 | 505/515 | Gree |

| 1000 | 350/440 | Light Blue |

Animals that were prepared for TEM imaging received a 200μL tail vein injection of either 50 (Nanocs) or 250 (Cytodiagnostics) nm diameter gold nanoparticles (0.01% by weight). After 6 hours the animals were perfused as described above. Tissue near the implant was isolated and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for one hour. The tissue samples were then washed in cacodylate buffer, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, rinsed in buffer, and en bloc stained with 2% uranyl acetate in maleate buffer at pH 5.2. After staining the samples were rinsed in distilled water, dehydrated in sequential ethanol solutions, infiltrated with Embed812 resin (Electron Microscopy Science), and baked overnight at 60 C. 60 nm sections were cut using a Leica UltraCut UCT, collected on carbon coated grids, and then stained using uranyl acetate and lead citrate.

2.2. Imaging and Immunohistochemistry

Sections were incubated in PBS for 5 minutes to rehydrate the tissue and remove the OCT compound. Coverslips were mounted using a fluorescent mounting media with DAPI (Vectashield, Vector Labs). Epifluoresence imaging was performed using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M microscope and Volocity software (Perkin Elmer). Confocal imaging was performed using a Leica TCS SP5 Spectral confocal microscope and software. All image analysis was done using Volocity.

Immunofluorescent staining was done according to standard protocols. Primary antibodies against GFAP and collagen IV (Abcam) were used at dilutions of 1:1000 and 1:400. A FITC conjugated secondary antibody was used at a dilution of 1:200. A rhodamine conjugated antibody against mouse IgG was used to stain for endogenous IgG (1:100, Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Electron microscopy was conducted to confirm the size of the nanoparticles and to visualize the gold nanoparticles in brain tissue. For SEM imaging, nanoparticles were sputter coated with carbon and imaged using a Hitachi SU-70 SEM at the Yale Institute for Nanoscience and Quantum Engineering core facility. TEM images of brain tissue slices were taken using the Yale School of Medicine’s EM core facilities’ FEI Tecnai Biotwin TEM at 80kV. TEM images were taken using a Morada CCD camera and iTEM (Olympus) software.

The relative amount of nanoparticles in the near implant tissue was determined using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices). An array of 5 by 10μm regions, extending from the implant edge to 110 μm into the tissue, was created on representative fluorescent images. The image was subjected to a threshold for each nanoparticle channel, and the total amount of pixels above the threshold was calculated for each region. Student’s t-tests were used to compare 200 and 500 nm particles to 20 nm particles in Excel (Microsoft).

2.3. Nanoparticle circulation and uptake

To confirm nanoparticle circulation and evaluate nanoparticle uptake by circulating monocytes, nanoparticles were injected into the tail vein of normal mice and allowed to circulate as described earlier. After 6 hours the blood was drawn by cardiac puncture and mixed with acid citrate dextran (Sigma) to prevent coagulation. The blood from 3 mice was diluted 1:1 with media (IMDM (Gibco) with 20% fetal bovine serum and penicillin, streptomycin, and l-glutamine), layered on Ficoll-Paque Premium (GE Healthcare), and centrifuged for 30 minutes at 400Xg. The buffy coat was reserved and washed with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS, Cellgro) to remove the free nanoparticles that were also initially contained in the buffy coat. The cells were resuspended in media and plated in permanox plastic chamber slides (Labtek). After two hours the monocytes had adhered and the slides were repeatedly washed with HBSS. The cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 20 minutes at room temperature, washed twice for five minutes with PBS with 0.1% Triton-x (American Bioanalytical), and stained with Alexa 488 linked phalloidin (diluted 1:100 in PBS, Invitrogen) for 40 minutes to reveal the actin cytoskeleton. The slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting media containing DAPI and imaged using a confocal microscope.

3. Results

3.1. Nanoparticles accumulate in near implant tissue

Numerous studies have monitored the extravasation of blood proteins to monitor the integrity of the BBB at implant sites. However, this approach does not provide information regarding the actual size of the BBB defects. To address this limitation, we used polystyrene nanoparticles to determine the size of near implant BBB leakage. Polystyrene nanoparticles are stable, non-degradable, have a uniform size distribution, and are available loaded with fluorescent compounds possessing various emission spectra (supplemental figure 1). SEM images of both 200 and 500 nm diameter particles illustrate that the nanoparticle tracers were both spherical and measured close to the nominal size. Nanoparticles with four different emission wavelengths were used in this study (supplemental figure 1C). Tracers were used with emissions in either the blue, green, red, or far red regions, and showed minimal overlap in signal.

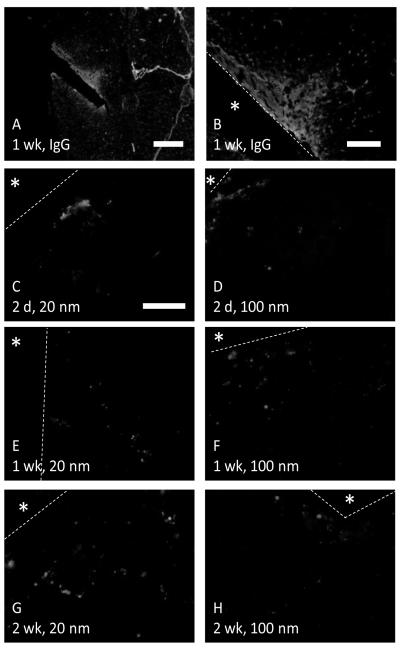

Fluorescent nanoparticles with diameters of either 20 or 100 nm were delivered via the tail vein into implant bearing mice. Nanoparticles of both sizes were observed in the peri-implant tissue, within the area of BBB leakage defined by IgG immunostain (figure 1). 20 nm and 100 nm particles were highly concentrated in specific regions within 50 to 100μm of the implant border. Nanoparticles were observed in the tissue at up to 2 weeks of implant duration, suggesting that the BBB leakage persists following the acute injury phase.

Figure 1.

Nanoparticles show near implant BBB leakage. Red nanoparticles of either 20 (C, E, G) or 100 (D, F, H) nm are visible in the area of leakage defined by IgG immunostain (A, B). The localized accumulation of nanoparticles contrasts with the homogeneous distribution of IgG around the implant. The implant is indicated by an asterisks and the border is marked by a yellow dashed line. Scale bar is 500μm for A, 150μm for B, and 50μm for C-H.

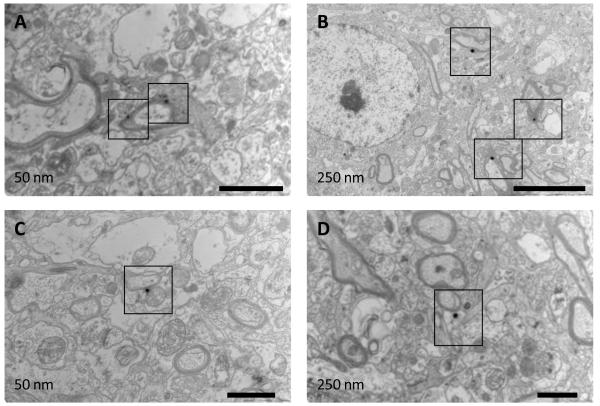

Detection of nanoparticles with fluorescence microscopy does not provide information about their exact location relative to the local neuroanatomy. To overcome this limitation, we used gold nanoparticle tracers and examined their location via TEM, which allowed us to confirm their presence outside of the vasculature. Specifically, 50 and 250 nm gold nanoparticles were delivered into implant bearing mice using the same techniques employed for the PS nanoparticles. Examination of multiple images showed extravasation of nanoparticles in the vicinity of implants (figure 2). Both 50 and 250 nm gold particles were observed in the parenchyma. The nanoparticles were extravasated and in contact with cellular processes. Moreover, 250 nm particles were observed in close proximity to myelinated axons.

Figure 2.

TEM images show gold nanoparticles in the brain parenchyma. Implant bearing mice were given injections of either 50 or 250 nm gold nanoparticles after 2 weeks of implant duration. Mice were perfused, and the brain tissue near the implant was isolated and prepared for TEM imaging. Both 50 nm (A, C) and 250 nm (B, D) nanoparticles (identified by black boxes) are visible as dark, electron dense, areas in the images. The particles are not within the vasculature. Nanoparticles in image B are visible near myelinated axons. Scale is 1μm for A, C and D and 5μm for B.

3.2. Infusion of a mixture of nanoparticles with variable sizes shows BBB gaps up to 500 nm

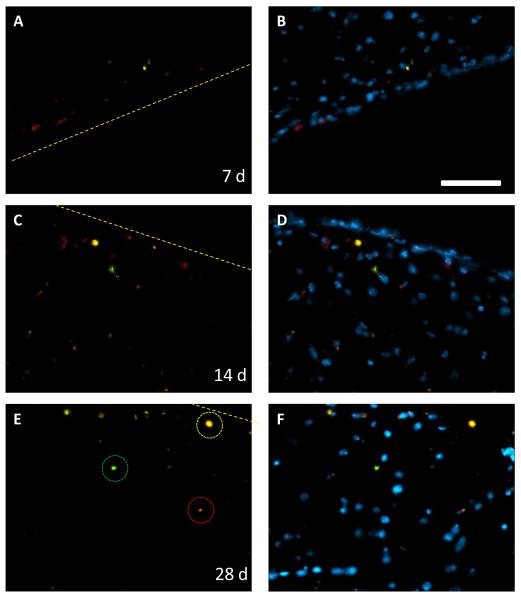

A nanoparticle tracer mixture containing particles with diameters ranging from 20 nm up to 1μm was used to evaluate the size of peri-implant BBB gaps. A solution with multiple sizes of nanoparticles, all with separate fluorescent excitation and emission wavelengths, was administered in a single tail vein injection. Analysis of brain tissue sections indicated that nanoparticles with diameters of 20, 200, and 500 nm were present in the brain parenchyma next to the implant. In contrast, 1μm diameter particles were excluded (figure 3). The tracers are located in both distinct, single size groups (highlighted in figure 3E), and in groups with multiple sizes of tracers. The presence of the distinct groups indicates heterogeneity in the BBB gaps that allow certain sizes of nanoparticles to pass through. It also highlights the ability of our imaging methods to separate the nanoparticles by their individual spectra. Merged images with a DAPI nuclear stain show nanoparticles primarily in areas with extensive cellular accumulation. These are likely part of the glial scar that forms due to the presence of the foreign material.

Figure 3.

Nanoparticle tracers show BBB gaps of multiple sizes. Equal amounts of 20, 200, 500, and 1000 nm particles were administered in a single tail vein injection. Nanoparticles of 20 (red), 200 (yellow) and 500 (green) nm are then visible in the brain at up to 4 weeks of implant duration. Tissue areas with distinct groups of 20, 200, or 500 nm are circled in E. Merged images with DAPI (B, D, F) show that nanoparticles are primarily located in areas with a high cellular density. Scale bar is 50μm, dashed line indicates implant border.

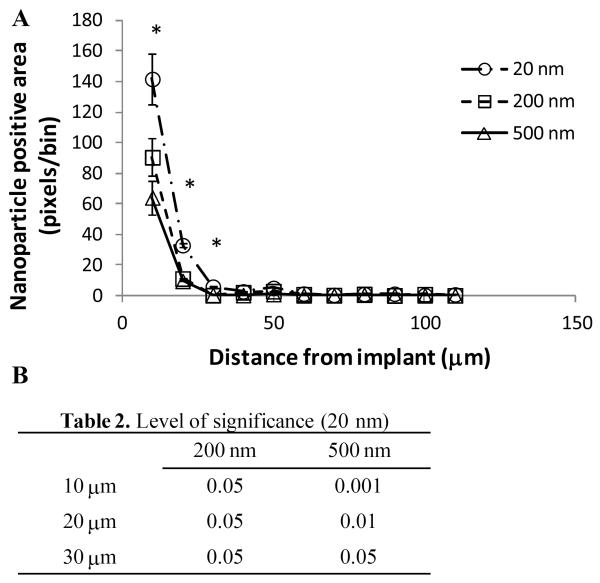

Metamorph software was used to measure the amount of nanoparticle signal in an array of 5 by 10μm bins set adjacent to the implant. Using this method we determined that there was a greater amount of 20 nm particles at distances of 10, 20 and 30μm from the implant when compared to 200 and 500 nm particles (figure 4). In this analysis, 95% of all nanoparticles are located within 30μm from the implant. There was no significant difference between the two larger particle groups.

Figure 4.

BBB is more permeable to smaller particles during the FBR. The amount of nanoparticle positive pixels per 5 ×10μm bin was measured at 10μm intervals away from the implant/tissue interface (A, mean ± SEM). 20 nm particles were present at a significantly greater amount when compared to both 200 and 500 nm particles at distances of 10, 20, and 30μm from the implant (levels of significance listed in table 2). There was no significant difference between the 200 and 500 nm particles. 95% of the total nanoparticles in the tissue are within 30μm of the implant.

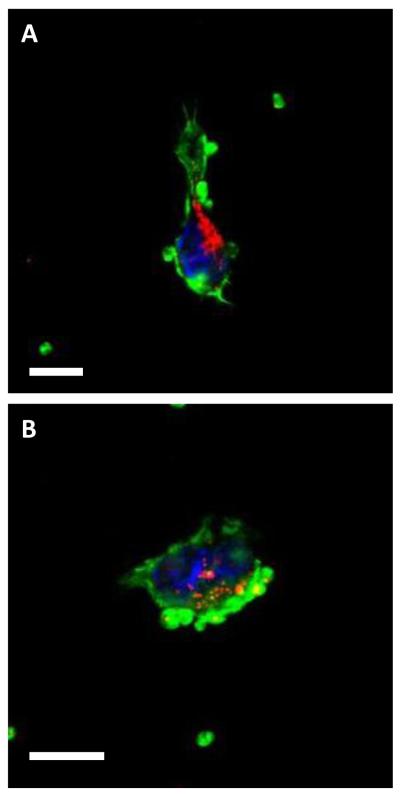

3.3. Confocal imaging shows nanoparticles near reactive astrocytes and vasculature

Based on our nanoparticle detection and TEM analysis we concluded that nanoparticles are able to enter into the brain parenchyma and interact with CNS cells, including neurons. Immunohistochemical analysis coupled with confocal microscopy allowed us to observe nanoparticles in close proximity to blood vessels and reactive astrocytes (figure 5). Specifically, we detected nanoparticles in close proximity to structures that were immunoreactive for Collagen IV, which is a component of the blood vessel basement membrane (figure 5A). In addition, we observed nanoparticles in brain tissue that did not contain collagen IV-positive structures. Because reactive astrocytes are the predominant cell type in the brain FBR, we used immunohistochemistry to detect GFAP, a reactive astrocyte-specific protein, and detected multiple size nanoparticles in close proximity to these cells (figure 5B, supplemental figure 2).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical stains show nanoparticles near blood vessels and reactive astrocytes. Tissue sections from 4 week implants were stained for collagen IV (A) or GFAP (B) to reveal blood vessels and reactive astrocytes respectively. Nanoparticles of multiple sizes (20 nm red, 200 nm yellow, and 500 nm green) are visible near a vessel (green) in 5A. Multiple sizes of nanoparticles are also visible in an area dense with reactive astrocytes (green) in 5B (separate channels in supplemental figure 2). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue) Scale is 50μm in A and 20μm in B.

3.4. Nanoparticle tracers are phagocytosed by circulating monocytes

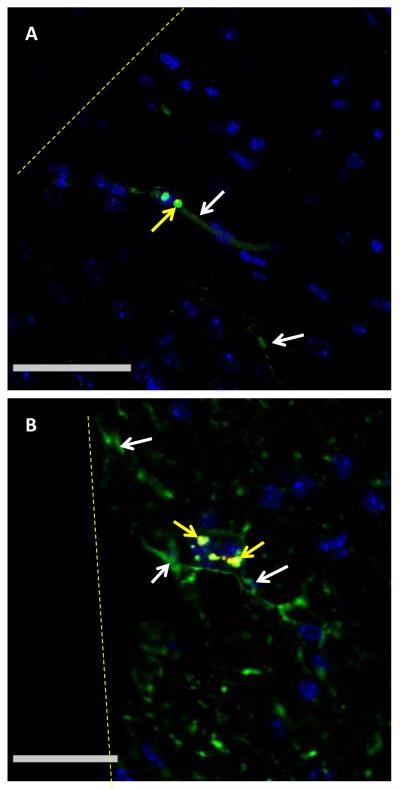

Our nanoparticle administration and detection method allowed the demonstration of nanoparticle extravasation in the brain FBR well after the acute inflammatory phase. TEM and confocal microscopy also suggested that extravasation though BBB gaps is a probable method of nanoparticle transport into brain parenchyma. However, another potential mechanism could involve the facilitated transport of nanoparticle into the brain tissue by circulating monocytes that phagocytose the tracers and then extravasate as part of the inflammatory response. Uptake of nanoparticles by monocytes in circulation was evaluated by injecting 100 nm nanoparticle tracers into the tail veins of mice without intracranial implants. After six hours the blood was removed by cardiac puncture and the monocytes were separated by gradient centrifugation. Because their density is close to the density of ficoll, free nanoparticles were enriched in the buffy coat. Isolation and examination of the monocyte-enriched buffy coat by confocal microscopy revealed both free and cell-associated nanoparticles (figure 6).

Figure 6.

Fluorescent nanoparticles are phagocytosed by circulating monocytes. 100 nm fluorescent nanoparticles (red) are visible in Alexa 488 linked phalloidin (green)-stained monocytes isolated 6 hr after tail vein injection. Scale is 10μm in A and B.

4. Discussion

BBB leakage is a significant complication of the brain FBR. Exposure of neurons to serum proteins and small molecules provides pro-apoptotic signals that lead to neuronal death and could prolong the duration of neuroinflammation (18, 26-28). Thus, approaches to induce the timely repair of the BBB would be essential for maintaining a healthy neuronal network at the tissue-implant interface. Towards this end, a better understanding of the nature of the BBB leakage, including definition of the size and duration of the disruption of the physical barrier, is needed.

Current methods of assaying BBB integrity rely on the imaging of macromolecular tracers in the tissue or on histochemical examination for serum proteins (29-31). These methods are able to show the extent of leakage, the gross tissue area exposed to serum, and the general kinetics of BBB healing. However, the largest tracer typically used for these measurements is IgG, which has a size of 11 nm. Using these methods could significantly underestimate the size of molecules that are able to transport into the brain. They also provide little detail on the physical aspects of BBB repair.

The use of nanoparticle tracers allows for a more precise determination of the size of defects in the BBB. Our research shows nanoparticles of up to 500 nm in diameter are able to access the brain parenchyma during the FBR at time points up to 4 weeks after implantation. This is a significant increase in size from previous measurements made with tracers of 11 nm in size or smaller. In addition, the nanoparticles are administered shortly before tissue harvesting, which can reduce the background caused by endogenous protein accumulation in the tissue, increasing the precision of our time points. Therefore, this method could be used to characterize induced BBB disruption, where particles as large as viruses or cells are observed to pass into brain tissue (21).

Nanoparticle tracers improve the characterization of BBB leakage during the FBR. Traditional measures using Evans blue or albumin immunostain show a homogeneous spread of leakage around the implant. This distribution gives very little information about the sources of BBB leakage, or their location within the affected tissue. In this study we observed localized areas of brain tissue containing multiple sizes of nanoparticles in the brain. In contrast, areas of tissue with only a single size of nanoparticle we also present. There was also a greater amount of 20 nm particles in the tissue than large, 500 nm particles. This indicates a broad distribution of BBB gap size, from 500 to 20nm. It also shows that there are a greater amount of the smaller BBB gaps during the brain FBR. We can also assume that the particles are located near their point of extravasation, since their large size prohibits diffusion through the brain extracellular matrix (35). By increasing the size of the tracers we are able to show that both the sources of leakage and their location within the tissue are heterogeneous.

The FBR is a complex process which progresses from an acute phase, after the response to the initial trauma of implantation, and resolves into a chronic phase. Previous studies have shown that as the FBR progresses, the overall amount of leakage decreases, as measured by albumin immunohistochemistry (11, 15). This suggests a gradual repair and reestablishment of the BBB in the involved tissue. In contrast, we have observed that tracers up to 500 nm in diameter are able to pass across the BBB up to 4 weeks after implantation. Thus, while the overall amount of leakage may decrease, the presence of the nanoparticle tracers at 4 weeks indicates significant BBB damage persists during the chronic phase of the FBR. We chose this experimental endpoint because we previously demonstrated by immunohistochemistry complete resolution of BBB leakage by 8 wks (11, 15).

Fluorescent imaging limits the precision with which the location of the tracers within the tissue can be identified. During fluorescent imaging the anatomy of the tissue cannot be observed, allowing only the observation of the tracers relative to the implant border. Immunohistochemical stains combined with confocal imaging can help to colocalize tracers with certain cell populations. The small size of the tracers also precludes the observation of nanoparticles smaller than 100 nm, unless they are present in larger aggregates. Therefore, TEM must be used to visualize individual small particles.

Non-specific diffusion through gaps is the most likely mechanism for nanoparticles to cross the BBB during prolonged neuroinflammation. Consistent with this suggestion, we observed the association of nanoparticles with multiple cells types (endothelial cells, astrocytes, and neurons). However, it is possible that additional mechanisms contribute to movement of nanoparticles across the BBB. These include receptor- or adsorption- mediated transcytosis, facilitated transport inside transmigrating monocytes, and transport through the tight junctions between cells (18-20). Receptor-mediated transport would require the opsonization of the nanoparticles during circulation and then recognition of the “functional” nanoparticles by receptors along the BBB. However, the nanoparticles are likely to be coated primarily with albumin during circulation, and albumin has no specific receptor on brain capillaries (36, 37). Therefore, the high concentration of nanoparticles we observed near the implant is unlikely to be caused by facilitated transport alone.

Another possible mechanism is that the nanoparticles accumulate in circulating monocytes that then transmigrate into the tissue at the site of inflammation. As members of the mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS) peripheral blood monocytes are part of a population of cells that are designed to phagocytose circulating particles, and are then able transmigrate into tissue (38, 39). This method of facilitated transport has been evaluated before for the movement of serotonin across the BBB (40). In the intracranial implant model, neuroinflammation causes the secretion of chemokines, like MCP-1, that attract monocytes (41, 42). We have shown uptake of our circulating nanoparticles by monocytes (figure 6). However, there were also freely circulating nanoparticles recovered with the monocytes during density centrifugation, and free nanoparticles were also visible in the tissue. Macrophages can readily phagocytose particles of a few microns in diameter but we did not observe 1μm beads in the brain parenchyma. (43). If monocyte-mediated transport contributed to the observed accumulation of nanoparticles, then a portion of those nanoparticles should have been 1μm in size. Based on the observation of nanoparticles in the brain parenchyma by TEM and the lack of larger nanoparticles we speculate that facilitated transport is not a major contributor to nanoparticle accumulation.

Gaps in the order of 100-500 nm in the BBB suggest that drug-carriers could be delivered during the FBR to target various aspects of neuroinflammation. Previous attempts to reduce the FBR have been via localized implant-based drug delivery systems or surface modification of the implant (44-47). Intravascular delivery could attenuate the FBR without the limitations of implant-based systems, which include low drug loading and poor drug diffusion in the tissue. Nanocarriers are already available with the capabilities necessary to transport through the gaps in the BBB and deliver bioactive compounds (48, 49). Therefore, it is possible that the combination of implant design and drug delivery could be used to mitigate the local neurodegeneration caused by the chronic implantation of intracranial electrodes (9). Importantly, BBB leakage is also known to play a major role in CNS injury and many neurodegenerative diseases including stroke, epilepsy, inflammation, brain tumors, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s disease (29, 30, 50-53). Moreover, the BBB represents a critical obstacle to the delivery of drugs for the treatment of brain tumors. A better understanding of the nature of BBB injury and subsequent repair could indicate opportunities for therapeutic intervention and improve our ability to locally deliver targeted therapies.

5. Conclusions

A new method for probing BBB integrity was developed for evaluating BBB reformation during the brain FBR. Nanoparticles ranging in size from 20 to 500 nm were visible in the near implant tissue, indicating significantly larger gaps than previously estimated. Tracers of various sizes were spread in distinct areas of the brain, indicating that the BBB leakage is heterogeneous. This method improves on the results obtained using traditional macromolecular tracers and is well suited for use in examining additional CNS disease states.

Supplementary Material

6. Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge funding from NIH grant RO1GM072194, and by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) MTO under the auspices of Dr. Jack Judy through the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center, Pacific Grant/Contract No. N66001-11-1- RB420-G1. We also wish to acknowledge the advice and expertise of the Yale School of Medicine’s EM core facility.

Footnotes

Classification numbers: 87.85.-d, 87.85.D-, 87.85.J-,

References

- 1.Donoghue JP, Nurmikko A, Black M, Hochberg LR. Assistive technology and robotic control using motor cortex ensemble-based neural interface systems in humans with tetraplegia. J Physiol. 2007 Mar 15;579(Pt 3):603–11. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.127209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friehs GM, Zerris VA, Ojakangas CL, Fellows MR, Donoghue JP. Brain-machine and brain-computer interfaces. Stroke. 2004 Nov;35(11 Suppl 1):2702–5. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000143235.93497.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolelis MA. Actions from thoughts. Nature. 2001 Jan 18;409(6818):403–7. doi: 10.1038/35053191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson BS, Finley CC, Lawson DT, Wolford RD, Eddington DK, Rabinowitz WM. Better speech recognition with cochlear implants. Nature. 1991 Jul 18;352(6332):236–8. doi: 10.1038/352236a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maynard EM. Visual prostheses. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2001;3:145–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.3.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hetling JR, Baig-Silva MS. Neural prostheses for vision: designing a functional interface with retinal neurons. Neurol Res. 2004 Jan;26(1):21–34. doi: 10.1179/016164104773026499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochberg LR, Bacher D, Jarosiewicz B, Masse NY, Simeral JD, Vogel J, et al. Reach and grasp by people with tetraplegia using a neurally controlled robotic arm. Nature. 2012 May 17;485(7398):372–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polikov VS, Tresco PA, Reichert WM. Response of brain tissue to chronically implanted neural electrodes. J Neurosci Methods. 2005 Oct 15;148(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McConnell GC, Rees HD, Levey AI, Gutekunst CA, Gross RE, Bellamkonda RV. Implanted neural electrodes cause chronic, local inflammation that is correlated with local neurodegeneration. J Neural Eng. 2009 Oct;6(5):056003. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/6/5/056003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biran R, Martin DC, Tresco PA. Neuronal cell loss accompanies the brain tissue response to chronically implanted silicon microelectrode arrays. Exp Neurol. 2005 Sep;195(1):115–26. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian W, Kyriakides TR. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 deficiency leads to prolonged foreign body response in the brain associated with increased IL-1beta levels and leakage of the blood-brain barrier. Matrix Biol. 2009 Apr;28(3):148–59. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winslow BD, Tresco PA. Quantitative analysis of the tissue response to chronically implanted microwire electrodes in rat cortex. Biomaterials. 2010 Mar;31(7):1558–67. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams JC, Hippensteel JA, Dilgen J, Shain W, Kipke DR. Complex impedance spectroscopy for monitoring tissue responses to inserted neural implants. J Neural Eng. 2007 Dec;4(4):410–23. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/4/4/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McConnell GC, Butera RJ, Bellamkonda RV. Bioimpedance modeling to monitor astrocytic response to chronically implanted electrodes. J Neural Eng. 2009 Oct;6(5):055005. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/6/5/055005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian W, Sawyer A, Kocaoglu FB, Kyriakides TR. Astrocyte-derived thrombospondin-2 is critical for the repair of the blood-brain barrier. Am J Pathol. 2011 Aug;179(2):860–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winslow BD, Christensen MB, Yang WK, Solzbacher F, Tresco PA. A comparison of the tissue response to chronically implanted Parylene-C-coated and uncoated planar silicon microelectrode arrays in rat cortex. Biomaterials. 2010 Dec;31(35):9163–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potter KA, Buck AC, Self WK, Capadona JR. Stab injury and device implantation within the brain results in inversely multiphasic neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative responses. J Neural Eng. 2012 Aug;9(4):046020. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/9/4/046020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abbott NJ, Patabendige AA, Dolman DE, Yusof SR, Begley DJ. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis. 2010 Jan;37(1):13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheikov N, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Jolesz F, Hynynen K. Cellular mechanisms of the blood-brain barrier opening induced by ultrasound in presence of microbubbles. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004 Jul;30(7):979–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habgood MD, Begley DJ, Abbott NJ. Determinants of passive drug entry into the central nervous system. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2000 Apr;20(2):231–53. doi: 10.1023/A:1007001923498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burgess A, Ayala-Grosso CA, Ganguly M, Jordao JF, Aubert I, Hynynen K. Targeted delivery of neural stem cells to the brain using MRI-guided focused ultrasound to disrupt the blood-brain barrier. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thevenot E, Jordao JF, O’Reilly MA, Markham K, Weng YQ, Foust KD, et al. Targeted delivery of self-complementary adeno-associated virus serotype 9 to the brain, using magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound. Hum Gene Ther. 2012 Nov;23(11):1144–55. doi: 10.1089/hum.2012.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu HL, Hua MY, Yang HW, Huang CY, Chu PC, Wu JS, et al. Magnetic resonance monitoring of focused ultrasound/magnetic nanoparticle targeting delivery of therapeutic agents to the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Aug 24;107(34):15205–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003388107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marty B, Larrat B, Van Landeghem M, Robic C, Robert P, Port M, et al. Dynamic study of blood-brain barrier closure after its disruption using ultrasound: a quantitative analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012 Oct;32(10):1948–58. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zunkeler B, Carson RE, Olson J, Blasberg RG, DeVroom H, Lutz RJ, et al. Quantification and pharmacokinetics of blood-brain barrier disruption in humans. J Neurosurg. 1996 Dec;85(6):1056–65. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.6.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gingrich MB, Junge CE, Lyuboslavsky P, Traynelis SF. Potentiation of NMDA receptor function by the serine protease thrombin. J Neurosci. 2000 Jun 15;20(12):4582–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04582.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gingrich MB, Traynelis SF. Serine proteases and brain damage - is there a link? Trends Neurosci. 2000 Sep;23(9):399–407. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01617-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nadal A, Fuentes E, Pastor J, McNaughton PA. Plasma albumin is a potent trigger of calcium signals and DNA synthesis in astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Feb 28;92(5):1426–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belayev L, Busto R, Zhao W, Ginsberg MD. Quantitative evaluation of blood-brain barrier permeability following middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Brain Res. 1996 Nov 11;739(1-2):88–96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00815-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Vliet EA, da Costa Araujo S, Redeker S, van Schaik R, Aronica E, Gorter JA. Blood-brain barrier leakage may lead to progression of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2007 Feb;130(Pt 2):521–34. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayhan WG, Heistad DD. Permeability of blood-brain barrier to various sized molecules. Am J Physiol. 1985 May;248(5 Pt 2):H712–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.248.5.H712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richmon JD, Fukuda K, Maida N, Sato M, Bergeron M, Sharp FR, et al. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 after hyperosmotic opening of the blood-brain barrier. Brain Res. 1998 Jan 5;780(1):108–18. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu WR, Westergren H, Farooque M, Holtz A, Olsson Y. Systemic hypothermia following compression injury of rat spinal cord: reduction of plasma protein extravasation demonstrated by immunohistochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 1999 Jul;98(1):15–21. doi: 10.1007/s004010051046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown EB, Boucher Y, Nasser S, Jain RK. Measurement of macromolecular diffusion coefficients in human tumors. Microvasc Res. 2004 May;67(3):231–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thorne RG, Nicholson C. In vivo diffusion analysis with quantum dots and dextrans predicts the width of brain extracellular space. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Apr 4;103(14):5567–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509425103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pardridge WM, Eisenberg J, Cefalu WT. Absence of albumin receptor on brain capillaries in vivo or in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1985 Sep;249(3 Pt 1):E264–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1985.249.3.E264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vorbrodt AW, Trowbridge RS. Ultrastructural study of transcellular transport of native and cationized albumin in cultured goat brain microvascular endothelium [corrected] J Neurocytol. 1991 Dec;20(12):998–1006. doi: 10.1007/BF01187917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel HM, Moghimi SM. Serum-mediated recognition of liposomes by phagocytic cells of the reticuloendothelial system - The concept of tissue specificity. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1998 Jun 8;32(1-2):45–60. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schroit AJ, Madsen J, Nayar R. Liposome-cell interactions: in vitro discrimination of uptake mechanism and in vivo targeting strategies to mononuclear phagocytes. Chem Phys Lipids. 1986 Jun-Jul;40(2-4):373–93. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(86)90080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Afergan E, Epstein H, Dahan R, Koroukhov N, Rohekar K, Danenberg HD, et al. Delivery of serotonin to the brain by monocytes following phagocytosis of liposomes. J Control Release. 2008 Dec 8;132(2):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamagami S, Tamura M, Hayashi M, Endo N, Tanabe H, Katsuura Y, et al. Differential production of MCP-1 and cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant in the ischemic brain after transient focal ischemia in rats. J Leukoc Biol. 1999 Jun;65(6):744–9. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.6.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009 Jun;29(6):313–26. doi: 10.1089/jir.2008.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jay SM, Skokos EA, Zeng J, Knox K, Kyriakides TR. Macrophage fusion leading to foreign body giant cell formation persists under phagocytic stimulation by microspheres in vitro and in vivo in mouse models. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010 Apr;93(1):189–99. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He W, McConnell GC, Schneider TM, Bellamkonda RV. A novel anti-inflammatory surface for neural electrodes. Advanced Materials. 2007 Nov 5;19(21):3529. + [Google Scholar]

- 45.He W, McConnell GC, Bellamkonda RV. Nanoscale laminin coating modulates cortical scarring response around implanted silicon microelectrode arrays. Journal of Neural Engineering. 2006 Dec;3(4):316–26. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/3/4/009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhong YH, Bellamkonda RV. Dexamethasone-coated neural probes elicit attenuated inflammatory response and neuronal loss compared to uncoated neural probes. Brain Research. 2007 May 7;1148:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhong YH, Bellamkonda RV. Controlled release of anti-inflammatory agent alpha-MSH from neural implants. Journal of Controlled Release. 2005 Sep 2;106(3):309–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allard E, Passirani C, Benoit JP. Convection-enhanced delivery of nanocarriers for the treatment of brain tumors. Biomaterials. 2009 Apr;30(12):2302–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sawyer AJ, Piepmeier JM, Saltzman WM. New methods for direct delivery of chemotherapy for treating brain tumors. Yale J Biol Med. 2006 Dec;79(3-4):141–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008 Jan 24;57(2):178–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weiss N, Miller F, Cazaubon S, Couraud PO. The blood-brain barrier in brain homeostasis and neurological diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 Apr;1788(4):842–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muller DM, Pender MP, Greer JM. Blood-brain barrier disruption and lesion localisation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with predominant cerebellar and brainstem involvement. J Neuroimmunol. 2005 Mar;160(1-2):162–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carmeliet P, De Strooper B. Alzheimer’s disease: A breach in the blood-brain barrier. Nature. 2012 May 24;485(7399):451–2. doi: 10.1038/485451a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.