Abstract

Background

Although cryptococcosis mainly occurs in the central nervous system and lungs in immunocompromised hosts, it can involve any body site or structure. Here we report the first case of primary cryptococcosis of a lumbar vertebra without involvement of the central nervous system or lungs in a relatively immunocompromised individual with rheumatoid arthritis and scleroderma.

Case presentation

A 40-year-old Chinese woman with rheumatoid arthritis diagnosed 1 year beforehand and with a subsequent diagnosis of scleroderma was found to have an isolated cryptococcal infection of the fourth lumbar vertebra. Her main complaints were severe low back and left leg pain. Cryptococcosis was diagnosed by CT-guided needle biopsy and microbiological confirmation; however, serum cryptococcal antigen titer was negative. After 3 months of antifungal therapy with fluconazole the patient developed symptoms and signs of scleroderma, which was confirmed on laboratory tests. After taking fluconazole for 6 months, the progressive destruction of the lumbar vertebral body had halted and the size of an adjacent paravertebral mass had decreased substantially. On discharge symptoms had resolved and at an annual follow-up there was no evidence of recurrence on the basis of symptoms, signs or imaging investigations.

Conclusion

Although cryptococcosis of the lumbar vertebra is extremely rare, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis for patients with lumbar vertebral masses to avoid missed diagnosis, misdiagnosis and diagnostic delay. Early treatment with antifungals proved to be a satisfactory alternative to surgery in this relatively immunocompromised patient. Any residual spinal instability can be treated later, once the infection has resolved.

Keywords: Cryptococcosis, Lumbar vertebra, Rheumatoid arthritis, Scleroderma, Fluconazole

Background

Cryptococcus is an encapsulated fungus, which is widespread in soil, rotten food and avian feces, especially pigeon droppings [1]. Cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans var neoformans (CNVN) is most likely to occur in immunocompromised hosts with cell-mediated immune deficiency, and is generally viewed as an opportunistic infectious disease [2-4], as there are only a handful of case reports of established infection in immunocompetent individuals [5,6]. Compared with CNVN, Cryptococcus neoformans var gattii (CNVG) is far more pathogenic and may infect immunocompetent hosts, with a recent outbreak attracting public attention [2,7]. CNVN and CNVG are increasingly thought to be separate species [8]. It is believed that cryptococcosis occurs upon inhalation of fungal propagules, which can then spread to involve any body site or structure through the blood or lymphatic system [3,6]. The central nervous system (CNS) and lungs are the sites most commonly affected, while the skeletal system is involved in 5-10% of all disseminated Cryptococcus infections [9-12]. Here, we present a case of primary cryptococcosis involving the fourth lumbar vertebra without respiratory or CNS involvement in a relatively immunocompromised individual with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and scleroderma.

Case presentation

A 40-year-old Chinese woman presented to our hospital complaining of low back pain that had been radiating to the left leg for the past 2 months. She reported significant weight loss of 7 kg, but no fever, chills, night sweats, productive cough, headache, dizziness, nausea or vomiting. One year earlier, she had been diagnosed with RA and took oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the first 3 months after the diagnosis. She had no history of tuberculosis or exposure to patients with tuberculosis. There was also no history of trauma to the back or leg and no loss of bowel or bladder function. She worked as a housewife and kept pigeons as pets, which she fed daily.

On admission, the patient was in considerable discomfort. She was apyrexial. Cardiac and abdominal examinations were normal, but on examination of the chest inspiratory crepitus was detected in the lower right lung base. Mild tenderness was found in the back around the L4 area and movement of the spine was restricted. Motor examination was normal, with normal power in both legs, but tactile hypoesthesia of the right medial femoral condyle was evident. The straight leg raising test (SLRT) elicited pain at 70° on the left and was pain free to 90° on the right. The right patellar reflex was normal, but it was diminished on the left. There were no skin nodules.

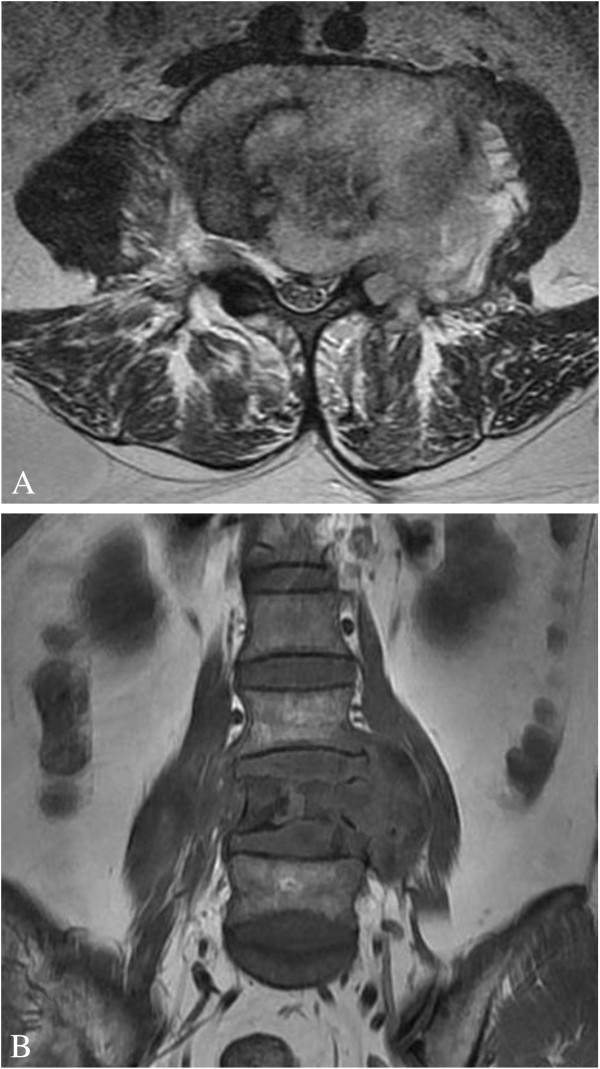

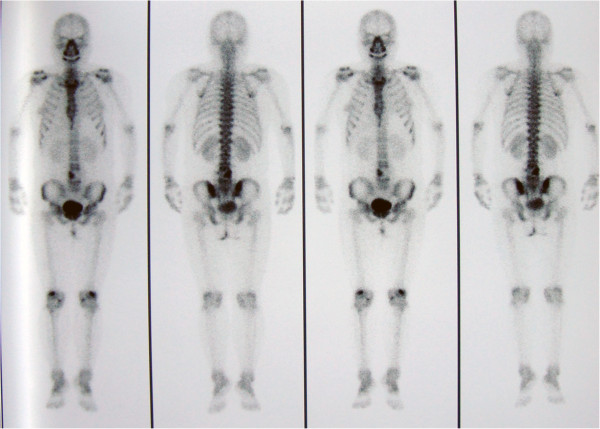

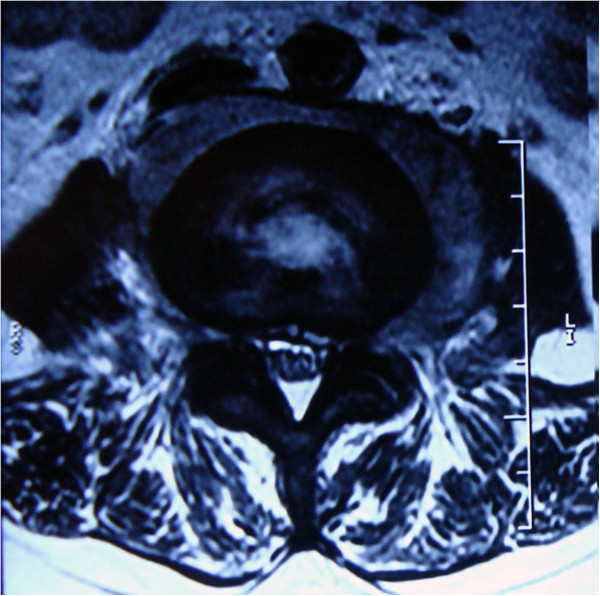

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) undertaken in August 2010 demonstrated osteolytic lesions of the fourth lumbar vertebral body (L4) that involved the left pedicle and transverse process causing secondary spinal canal stenosis at that level (Figure 1A, 1B). Moreover, a paravertebral soft tissue mass was seen on both sides that was larger on the left. The intervertebral discs were relatively preserved. Single photon emission-computed tomography (SPECT) showed increased uptake of technetium-99 m in the L4 vertebra (Figure 2). Routine blood tests revealed: a white blood cell count of 6500/μL with 73.1% neutrophils (normal range: 50-70%), 16.3% lymphocytes (normal: 20-40%), 1.1% eosinophils (normal: 0.5-5%), 0.2% basophils (normal: 0-1%) and 8.5% monocytes (normal: 3-8%); a hemoglobin of 10.7 g/dL (normal: 11.0-16.0 g/dL) and a platelet count of 368,000/μL (normal: 100,000-300,000/μL). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 22 mm/h (normal: <20 mm/h) and the C-reactive protein (CRP) was 1.45 mg/dL (normal: <0.80 mg/dL). Tumor markers (including alpha fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, β2-microglobulin, ferroprotein and estradiol) were not elevated, serum cryptococcal antigen and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies were negative, but the tuberculin test (PPD skin test) was strongly positive.

Figure 1.

MRI of the lumbar vertebrae. (A) Transverse section imaging of L4 showed the involvement of left pedicle and transverse process, the paravertebral soft tissue mass and the spinal canal stenosis. (B) Coronal section imaging of lumbar vertebrae showed the osteolytic lesions of vertebral body at L4 level.

Figure 2.

SPECT examinations. Increased uptake of technetium-99m in the area of L4 vertebrae.

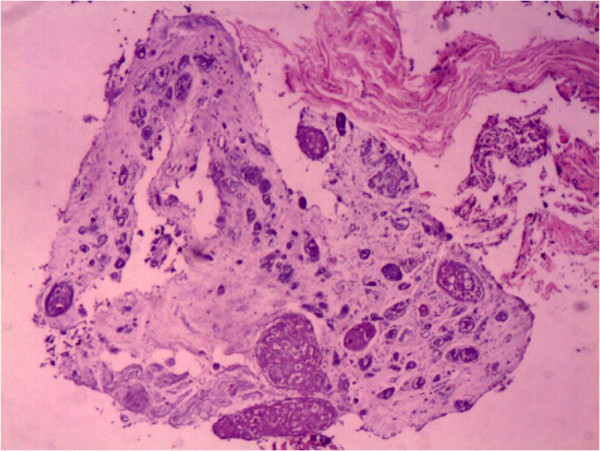

A definitive diagnosis could not be established at this stage. Fourteen days later we performed a CT-guided needle aspiration biopsy and sent the material for culturing of bacteria, Mycobacteria and fungi, and also for histopathological analysis. The latter revealed atypical granulomas and large quantities of necrotic tissue with scattered fungal organisms that were identified as Cryptococcus by subsequent periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and Gomori’s methenamine silver (GMS) staining (Figure 3). No malignant cells or epithelioid granulomas were observed in this specimen. Microbial culture revealed the growth of Cryptococcus sensitive to fluconazole (FLC) and flucytosine (5-FC), while Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture was negative. Because of limited clinical laboratory facilities, we could not conduct tests to distinguish CNVN from CNVG. Considering the antimicrobial sensitivity test results and the side effects of amphotericin B (AMB) and 5-FC, the patient was administered FLC 400 mg/d orally. The patient declined lumbar puncture that would have allowed examination of cerebrospinal fluid.

Figure 3.

Histopathological analysis of the paravertebral mass. Atypical granulomas and massive necrotic tissue with scattered fungal organisms (haematoxylin and eosine staining ×10).

After 3 months of FLC, the patient complained of pale hands brought on by cold and a sensation of stiffness under the skin in the face and distal extremities: these areas felt indurated on palpation. Laboratory tests found: an elevated γ-globulin (22.3%, normal range: 9.0-16.0%); reduced albumin (57.9%, normal: 60-71%); an immunoglobulin G of 1960 mg/dL (normal: 751-1560mg/mL); a rheumatoid factor (RF) of 29 IU/mL (normal: <29 IU/mL); a circulating immune complex (CIC) of 18 U/mL (normal: <13 U/mL) and an anti-citrulline-containing peptide antibody (anti-CCP) of 20.9 U/mL (normal: <12 U/mL). Also, extractable nuclear antigen anti-Smith surface antigen antibody (ENA anti-SSA antibody), extractable nuclear antigen anti-U1 ribonuleoprotein antibody (ENA anti-U1RNP antibody) and extractable nuclear antigen anti-Scl-70 antibody (ENA anti-Scl-70 antibody) were all positive and antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer was 1:400 (normal: <1:80). ESR had risen to 56 mm/h. As a result, she was diagnosed with scleroderma and was treated with total glucosides of paeony capsules for 16 days. Immunosuppressants were avoided because of concerns about ongoing disseminated infection.

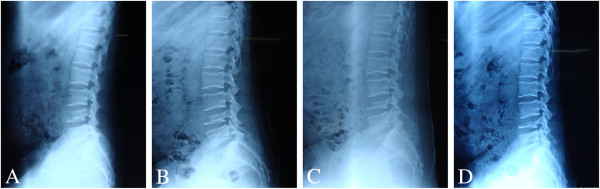

During treatment with FLC, a plain X-ray of the lumbar spine was taken every 4 weeks (Figure 4). The X-ray taken in December 2010 (Figure-4D) showed no significant changes when compared with that of the previous month (Figure-4C), suggesting that the destruction of the lumbar vertebral body had abated. Meanwhile, the MRI of November 2010 (Figure 5) showed that the size of the paravertebral mass had decreased when compared with the examination undertaken in August 2011 and the spinal cord compression had been substantially alleviated. After 6 months of continuous oral FLC, her low back and left leg pain had completely resolved. Meanwhile, tactile sensation over the right medial femoral condyle, the SLRT of the left lower limb and the left patellar tendon reflex had recovered to normal. The patient was discharged having made a full recovery and remained asymptomatic and with no radiological evidence of relapse at 12-month follow-up.

Figure 4.

Plain X-ray of lumbar spine taken every 4 weeks during the treatment with fluconazole. (A and B) September and October. (C and D) No significant changes were found between the imaging taken in November and December.

Figure 5.

MRI of the lumbar vertebra taken in November 2010. The decreased mass and the alleviated spinal cord compression.

Discussion

Cryptococcosis is rare disease in man and mainly affects the immunocompromised [4]. It is extremely rare in immunocompetent hosts, with an estimated incidence of 0.2 per million per year [13]. The CNS and lungs are most commonly affected and involvement of the musculoskeletal system is uncommon [9]. When bone is affected, the rarest form is a primary infection without involvement of other tissues [12].

On reviewing the English language literature reported since 2000 we found 14 cases (Table 1), including ours, of skeletal cryptococcosis [5,9,14-24]. Among these cases, a total of 28 bony sites and joints were affected, of which 11 were vertebrae, suggesting that vertebral involvement is most common. This finding is consistent with that of John Chleboun [12]. In 1977 he reported a case series of 56 patients in which the vertebrae were involved on 25 occasions out of a total of 117 bony sites and joints. Of the 14 cases, the proportion of men to women was 5:9 and the average age was 37.8 years (range 19-84). Reports published since 2000 do not suggest any predilection for age or gender [14], but this might be a consequence of the small number of reports.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of 14 cases with skeletal cryptococcosis

| Case no./Reference | Age (yr)/sex | Underlying diseases | Immunosuppressive therapy | Bones and joints | Treatment | Outcome | Follow up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/[15] |

27/F |

Lymphocytopenia |

None |

Left iliac crest, left acetabulum, left femur |

Surgery, amphotericin B, fluconazole, itraconazole |

Alive (good health) |

12 months |

| 2/[18] |

24/F |

Sarcoidosis |

None |

T1, T2, T3 |

Percutaneous puncture drainage, fluconazole, flucytosine, amphotericin B |

Alive (no relapse) |

16 months |

| 3/[14] |

42/M |

Diabetes mellitus, renal transplantation |

Prednisone, azathioprine, prograf |

Left elbow joint, left wrist joint |

Sugery, fluconazole |

Alive (complete resolution) |

6 months |

| 4/[5] |

24/F |

Tuberculosis |

None |

T2, T3, left 3th rib |

Surgery, fluconazole, amphotericin B |

Died 2 weeks after the surgery |

None |

| 5/[19] |

20/M |

Sarcoidosis |

Prednisone |

T12, L1, L2 |

Fluconazole |

Alive (asymptomatic) |

6 months |

| 6/[17] |

22/M |

None |

None |

Left 9th rib |

Surgery, fluconazole, amphotericin B |

Alive (normal) |

12 months |

| 7/[20] |

19/F |

Sarcoidosis |

Prednisone |

Left humeral head |

Fluconazole, amphotericin B |

Alive (lesion smaller) |

1 month |

| 8/[21] |

84/F |

Bullous pemphigoid, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, congestive heart failure, hypothyroidism, hypercholesterolemia, atrial fibrillation, degenerative joint disease |

Prednisone, azathioprine |

Proximal phalanx, intermediate phalanx |

Fluconazole, amphotericin B, flucytosine |

Died (The cause of death was unknown, and no autopsy was performed.) |

None |

| 9/[16] |

34/F |

None |

None |

L4, L5 |

Percutaneous puncture drainage, fluconazole |

Alive (full recovery ) |

None (lost to follow-up) |

| 10/[9] |

38/F |

Lymphocytopenia |

None |

Skull vault |

Fluconazole |

Alive (eradicate the infection) |

None (not mentioned) |

| 11/[22] |

54/F |

None |

None |

Right frontal bone |

Surgery, fluconazole, flucytosine, amphotericin B |

Alive (asymptomatic) |

6 weeks |

| 12/[24] |

38/M |

Testicular cancer, sarcoidosis |

None |

Left clavicle |

Surgery, fluconazole |

Alive |

None (not mentioned) |

| 13/[23] |

35/M |

Tuberculosis, HIV |

None |

Left humerus. Left radius, left ulna, left 5th metacarpal |

Sugery, fluconazole, amphotericin B |

Alive (improved markedly) |

19 months |

| 14* | 40/F | Rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma# | None | L4 | Fluconazole | Alive (no relapse) | 12 months |

* Present case. # The scleroderma was diagnosed after the therapy with FLC for 3 months.

In all 14 of the more recent cases, 11 had been diagnosed with other diseases before cryptococcosis (Table 1). Five of the 11 presented with a classical immunodeficiency caused by HIV or immunosuppressant therapies and the remainder had diagnoses consistent with relative immunodeficiency such as sarcoidosis, lymphocytopenia, tuberculosis, diabetes mellitus, renal transplantation, RA and scleroderma [14,25-27]. Thus, complete and relative immunocompromise appear to be the most important risk factors for skeletal cryptococcosis, a view that is consistent with previous reports [5,14,15].

Of the 13 cases reported in the literature, tests to distinguish CNVN from CNVG were not undertaken, despite three cases occurring in the subtropics when CNVG is traditionally viewed as a tropical and subtropical organism [28]. We did not attempt to differentiate between CNVN and CNVG. Cryptococcosis caused by CNVG has never been reported in China, is generally geographically restricted and the patient had no history of travel to areas where CNVG is endemic. Finally, the patient had a history of exposure to pigeon feces, which has been described as a risk factor for CNVN infection rather than CNVG [29,30]. It could be argued that it is important to differentiate between the two organisms because of differences in antifungal susceptibility and the changing ecology and virulence of CNVG [31-33]. We recommend that they should be distinguished if possible to aid diagnosis, direct treatment and improve understanding of the disease.

In our case, the PPD skin test was strongly positive, which suggests active infection with Mycobacteria. But the history, clinical symptoms and signs, imaging examinations, mycobacterial culture and histopathological analysis did not support the diagnosis. Hence, lumbar tuberculosis was excluded and we are not able to explain the positive result.

Skeletal cryptococcosis is rare but treatable. Substantial morbidity and mortality can arise from missed diagnosis, misdiagnosis or delay in diagnosis [34]. According to a review of 11 cases of spinal fungal infections, the average delay in diagnosis for 10 of the patients was 99 days and in the last case it took 9 years before the definitive diagnosis was made [35]. One explanation is that the history and radiologic findings resemble a variety of other infectious and neoplastic disorders [36], another is a lack of suspicion of cryptococcosis. Clinicians should be alert to Cryptococcus infections and consider appropriate investigations that might contribute to a definitive diagnosis. Cryptococcosis is usually diagnosed by means of a combination of hematological tests, imaging examinations, biopsies and microbial culture. The following should arouse suspicion of the diagnosis. First, although serum cryptococcal antigen is an accurate indicator of cryptococcal infection, it is not positive in all cases [15,16,19,22], just like ours. Second, imaging examinations may lack specificity, resulting in the need for further examinations to differentiate the disease from tuberculosis, neoplastic disorders and yaws, for example. It is noteworthy that the imaging and surgical findings of vertebral cryptococcosis can mimic spinal tuberculosis [5], so biopsies and microbial culture are essential to make the definitive diagnosis.

Of the 14 cases reported since 2000, five were cryptococcosis of the spine (Table 1). All five received antifungal chemotherapy even though there have been cases cured with surgery alone [12]. One of the five was treated with both surgery and antifungal drugs, but the patient died soon afterwards. The cause of death was attributed to the delay in diagnosis and hepatic failure provoked by antitubercular treatment (ATT) [5]. Two of the five cases received at least two types of antifungal drug, while FLC was the sole agent in the other three. Although skeletal cryptococcosis has been most frequently treated with AMB and/or 5-FC [14,17,18], the serious side effects of these drugs led us to prescribe FLC 400 mg/d orally alone for this patient, in compliance the guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) [37]. We were also guided by the sensitivity of the organism grown on culture. Surgery was not offered despite symptomatic spinal cord compression, as we perceived an increased risk of disseminating the infection and at present there are no effective means of preventing this. Moreover, the stress response to surgery might predispose to disseminated infection. We recommend that antifungal agents should be the first line treatment for relatively immunocompromised hosts. Surgery should be considered only if antifungals prove to be ineffective. In this case, surgery to improve the stability of the lumbar spine would be offered at a later date.

Conclusions

Cryptococcosis of the lumbar vertebra should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with lumbar vertebral masses to avoid missed diagnosis, misdiagnosis and diagnostic delay. The successful management of cryptococcosis of the lumbar vertebra with fluconazole alone shows that antimicrobials are a plausible early treatment option that may obviate the need for surgery in relatively immunocompromised patients.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

CNVN: Cryptococcus neoformans var neoformans; CNVG: Cryptococcus neoformans var gattii; CNS: Central nervous system; RA: Rheumatoid arthritis; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; SPECT: Single photon emission computed tomography; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FLC: Fluconazole; 5-FC: Flucytosine; AMB: Amphotericin B

Competing interests

All authors have approved the submission and declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HXZ, GZN, SQF, HWJ, YL and WDR made substantial contributions to the clinical care. HXZ, GZN, HYF and WDR collected the patient data and involved in the interpretation of data. HXZ and GZN drafted the manuscript. SQF, HWJ and YL revised and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

HXZ: PhD Candidate of Orthopaedics. Department of Orthopaedics, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin, PR China. GZN: PhD Candidate and Attending Doctor of Orthopaedics. Department of Orthopaedics, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin, PR China. SQF: PhD and Professor of Orthopaedics. Department of Orthopaedics, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin, PR China. HWJ: Bachelor and Associate professor of Orthopaedics. Department of Orthopaedics, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin, PR China. YL: Master and Attending Doctor of Orthopaedics. Department of Orthopaedics, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin, PR China. HYF: Master of Orthopaedics. Department of Orthopaedics, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin, PR China. WDR: Master and Attending Doctor of Orthopaedics. Department of Orthopaedics, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin, PR China.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Heng-Xing Zhou, Email: kevin_zyfllxy@hotmail.com.

Guang-Zhi Ning, Email: ningguangzhi@gmail.com.

Shi-Qing Feng, Email: fengsq321@gmail.com.

Hong-Wei Jia, Email: kevin_zyf@126.com.

Yang Liu, Email: zhpliang0311@163.com.

Hong-Yong Feng, Email: fengyong236@sina.com.

Wen-Dong Ruan, Email: xiangtianfei2008@sina.com.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Radiological Department, the Laboratory Department and the Pathology Department of the Tianjin Medical University for their generous help. And there was no financial support to the work. We have obtained permission to acknowledge from all departments mentioned above.

References

- Henderson HM, Chapman SW. In: A practical approach to infectious disease. 4. Reese RE, Betts RF, editor. Boston: Little, Brown & Company; 1996. Infections due to fungi, actinomyces, and nocardia; pp. 672–675. [Google Scholar]

- Rozenbaum R, Gongalves AJR. Clinical epidemiological study of 171 cases of cryptococcosis. CIin Inf Dis. 1994;18:369–80. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjeh RA, Conn LA, Stephens DS, Baughman W, Hamill R, Graviss E, Pappas PG, Thomas C, Reingold A, Rothrock G, Hutwagner LC, Schuchat A, Brandt ME. Pinner RW; Cryptococcal Active Surveillance Group: Cryptococcosis: population-based multistate active surveillance and risk factors in human immunodeficiency virusinfected persons. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:449–54. doi: 10.1086/314606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idnurm A, Bahn YS, Nielsen K, Lin X, Fraser JA, Heitman J. Deciphering the model pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:753–64. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Chhabra R, Sharma BS, Das A, Khosla VK. Vertebral cryptococcosis simulating tuberculosis. Br J Neurosurg. 2003;17(6):556–571. doi: 10.1080/02688690310001626868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis JN, Harrison TS. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29(2):141–50. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1063853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronstad JW, Attarian R, Cadieux B, Choi J, D’Souza CA, Griffiths EJ, Geddes JM, Hu G, Jung WH, Kretschmer M, Saikia S, Wang J. Expanding fungal pathogenesis: Cryptococcus breaks out of the opportunistic box. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9(3):193–203. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovers M, Hagen F, Boekhout T. Diversity of the Cryptococcus neoformans-Cryptococcus gattii species complex. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2008;25:S4–S12. doi: 10.1016/S1130-1406(08)70019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit A, Sudish K, Pople IK. Primary calvarial cryptococcal osteomyelitis in a patient with idiopathic lymphopenia. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2008;150:713–714. doi: 10.1007/s00701-008-1608-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottebart HC, McGehee RF, Utz JP. Cryptococcus neoformans osteomyelitis: case report of two patients. Sabouraudia. 1974;12(2):127–32. doi: 10.1080/00362177485380181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliner JR, Wilkins EB, Fernald GW. Localized osseous cryptococcosis. J Pediatr. 1979;94(4):597–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(79)80020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chleboun J, Nade S. Skeletal cryptococcosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:509–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freidman GD. The rarity of cryptococcosis in Northern California: the 10 year experience of a large defined population. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117:230–234. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno KM, Farhoomand L, Libman BS, Pappas CN, Landry FJ. Cryptococcal arthritis, tendinitis, tenosynovitis, and carpal tunnel syndrome: report of a case and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:104–108. doi: 10.1002/art1.10249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanelli G, Sansoni A, Ricciardi B, Ciacci C, Cellesi C. Muscular-skeletal cryptococcosis in a patient with idiopathic CD4+ lymphopenia. Mycopathologia. 2001;149:137–139. doi: 10.1023/A:1007271822625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tawfiq JA, Ghandour J. Cryptococcus neoformans abscess and osteomyelitis in an immunocompetent patient with tuberculous lymphadenitis. Infection. 2007;35:377–382. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-6109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WC, Tzao C, Hsu HH, Chang H, Lo CP, Chen CY. Isolated cryptococcal thoracic empyema with osteomyelitis of the rib in an immunocompetent host. J Infect. 2005;51:e117–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PP. Successful treatment of cryptococcal osteomyelitis and paraspinous abscess with fluconazole and flucytosine. South Med J. 2001;94:936–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildstein MS, Martin SM Jr, Glaser JA. Cryptococcal osteomyelitis in a 20-year-old male with sarcoidosis. Spine J. 2005;5:467–70. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldshteyn N, Zanchi A, Cooke K, Agha R. Cryptococcal osteomyelitis of the humeral head initially diagnosed as avascular necrosis. South Med J. 2006;99:1140–1141. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000224744.75040.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins C, Flaherty JP. Cryptococcal Osteomyelitis of the Finger Complicated by Meningitis. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2007;15:345–347. doi: 10.1097/IPC.0b013e3180315170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed MU, Dacuycuy MA, Kennedy DJ. Cryptococcal Epidural Abscess with Bone Involvement: Case Report and Review of Literature. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2009;17:193–195. doi: 10.1097/IPC.0b013e3181812c14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burton R, Gogela N, Rebe K, McNally M, Meintjes G. Cryptococcal immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome presenting with erosive bone lesions, arthritis and subcutaneous abscesses. AIDS. 2009;23:2371–2373. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328330975f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller DS, Pope JB, Thornhill BA, Dorfman HD. Cryptococcal pyarthrosis and sarcoidosis. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38:721–727. doi: 10.1007/s00256-009-0691-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiertiburanakul S, Wirojtananugoon S, Pracharktam R, Sungkanuparph S. Cryptococcosis in human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10(1):72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang YM, Ho YC, Chang HT, Yu CJ, Yang PC, Hsueh PR. Disseminated cryptococcosis in HIV-uninfected patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27(4):307–310. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, Neal JJ, Holmberg SD. Unexplained opportunistic infections and CD4+ T-lymphocytopenia without HIV infection. An investigation of Cases in the United States. N Eng J Med. 1993;328:373–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302113280601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Shun L, Christopher H, Mody. Cryptococcus. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:186–196. doi: 10.1513/pats.200907-063AL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons CW. Saprophytic sources of Cryptococcus neoformans associated with the pigeon (Columba livia) Am J Hyg. 1955;62:227–232. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a119775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escandón P, Sánchez A, Martínez M, Meyer W, Castañeda E. Molecular epidemiology of clinical and environmental isolates of the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex reveals a high genetic diversity and the presence of the molecular type VGII mating type a in Colombia. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:625–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta K, Bartlett KH, Baer R, Byrnes E, Galanis E, Heitman J, Hoang L, Leslie MJ, MacDougall L, Magill SS, Morshed MG, Marr KA. Cryptococcus gattii Working Group of the Pacific Northwest: Spread of Cryptococcus gattii into Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1185–1191. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.081384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser JA, Giles SS, Wenink EC, Geunes-Boyer SG, Wright JR, Diezmann S, Allen A, Stajich JE, Dietrich FS, Perfect JR, Heitman J. Same-sex mating and the origin of the Vancouver Island Cryptococcus gattii outbreak. Nature. 2005;437:1360–1364. doi: 10.1038/nature04220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTaggart L, Richardson SE, Seah C, Hoang L, Fothergill A, Zhang SX. Rapid identification of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii, C. neoformans var. neoformans, and C. gattii by use of rapid biochemical tests, differential media, and DNA sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(7):2522–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00502-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevitz O, Goldschmied-Reuven A, Block C, Kopolovic J, Farfel Z, Hassin D. Cryptococcus neoformans vertebral osteomyelitis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32:315–318. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier DD, Campbell DR, Garvey TA, Wiesel S, Bohlman HH, Eismont FJ. Fungal Infections of the Spine: Report of Eleven Patients with Long-Term Follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:560–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickie JB, Walker T. Cryptococcosis (torulosis): Some problems in diagnosis and management. Australas Ann Med. 1964;13:229–39. doi: 10.1111/imj.1964.13.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saag MS, Graybill RJ, Larsen RA, Pappas PG, Perfect JR, Powderly WG, Sobel JD, Dismukes WE. Practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:710–718. doi: 10.1086/313757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]