Abstract

IL-33 is an IL-1 family cytokine that elicits IL-5-dependent eosinophilia in vivo. We show here that IL-33 promotes minimal eosinophil hematopoiesis via direct interactions with mouse bone marrow progenitors ex vivo and that it antagonizes eosinophil hematopoiesis promoted by IL-5 on SCF and Flt3L primed bone marrow progenitor cells in culture. SCF and Flt3L primed progenitors respond to IL-33 by acquiring an adherent, macrophage-like phenotype, and by releasing macrophage-associated cytokines into the culture medium. IL-33-mediated antagonism of IL-5 was reproduced in part by the addition of GM-CSF and was inhibited by the actions of neutralizing anti-GM-CSF antibody. These findings suggest that the direct actions of IL-33 on bone marrow progenitors primed with SCF and Flt3L are antagonistic to the actions of IL-5 and are mediated in part by GM-CSF.

1. Introduction

Eosinophils represent only a small fraction of the total leukocytes in peripheral blood at homeostasis. Interleukin-5 (IL-5), a cytokine produced by Th2 lymphocytes in response to asthma provocation, in atopic diseases, and during helminth infections elicits eosinophilia (reviewed in [1]). Numerous studies have documented the pivotal role played by IL-5 in promoting differentiation of eosinophils from committed hematopoietic progenitors in the bone marrow, a crucial component of this response [2]. We have used IL-5 in combination with other cytokines to generate eosinophils from bone marrow progenitors; our current protocol uses IL-5 on stem cell factor (SCF) and Flt3 Ligand (Flt3L)-stimulated unselected bone marrow cells to produce virtually pure eosinophils by day 10 to 12 of culture. We have characterized these cells extensively both phenotypically and functionally [3].

The recent identification and characterization of interleukin-33 (IL-33) has added a significant new dimension and complexity to our understanding of mechanisms promoting systemic eosinophilia. IL-33 is a member of the IL-1 cytokine family and has been implicated as a molecule of interest in a number of diseases including asthma, atherosclerosis, arthritis and obesity [4]. IL-33 is expressed in epithelial cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts and adipocytes [5–7]. IL-33 is an alarmin, and modulates Th2-type proinflammatory signals upon its release from necrotic cells and/or via atypical secretory pathways [5,8]. The IL-33 receptor ST2 (also known as IL1RL1) is found primarily on Th2 cells [9], but also on basophils [10], eosinophils [11] and mast cells [12]. Recently, natural helper cell [13], nuocyte [14], and type 2 innate cell [15] responses to IL-33 have also been documented. While the biology of this cytokine remains to be completely elucidated, IL-33 contributes to the synthesis and release of IL-5 from one or more of these numerous target cells, and thereby promotes eosinophilia [16]. In addition to these activities, several direct interactions between IL-33 and eosinophils have been examined and defined. IL-33 induces eosinophil degranulation and production of superoxide [11], elicits cytokine secretion in association with phosphorylation of intracellular signaling molecules ERK and IκB [17], augments expression of CD11b and enhanced adhesion [18], and modulates responsiveness to Siglec 8 [19].

Given these observations, our intent was to explore the direct interactions of IL-33 with bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors in order to determine whether IL-33 might promote eosinophil hematopoiesis ex vivo in a well-characterized bone marrow culture system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Mice

Six to eight-week old wild-type BALB/c mice were purchased from Division of Cancer Technologies (DCT, Rockville, MD). Interleukin-5 deficient (IL-5−/−) [20] and eosinophil-deficient ΔdblGATA mice [21], both on the BALB/c background, are maintained on site. This study was reviewed and all protocols were carried out in accordance with the NIAID Animal Care and Use Committee Guidelines (Animal Study Proposal LAD 7E).

2.2 Intraperitoneal injections, tissue collection and cell counts

IL-33 (R&D Systems) was administered via intraperitoneal injection at 0.1 μg per mouse per day for 7 consecutive days, after which serum samples were collected from individual mice on day 8 and tissues harvested on day 9. Cell recruitment in response to IL-33 was determined by flushing the peritoneal cavity of each mouse with 10 – 12 mL of 1% BSA in PBS; the total cell number was determined by hemacytometer counts, and 50,000 cells in 100 μL of 0.1% BSA in PBS were placed in a cytofunnel (Thermo Scientific) and centrifuged in a Shandon Cytospin 4 at 500 g for 5 minutes. The cytospin slides were stained with Diff Quik (Siemens, Newark, DE) as described [22]. Each slide was counted under a 64x oil immersion objective and eosinophils were reported as percent of total cells. Bone marrow cell suspensions were prepared from total cells from femurs and tibias flushed with RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA); red blood cells were subjected to hypotonic lysis, and the remaining cells were suspended in 0.1% BSA in PBS prior to determination of total cell number and preparation of cytospin slides. Single cell suspensions from spleen were obtained by cutting the tissue into small pieces in Hanks’ Buffered saline solution supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Lonza Bio Whittaker, Walkersville, MD) and 10 mM HEPES (Invitrogen). Fragments were passed through a 70 μm strainer followed by a 40 μm strainer. The red blood cells were subjected to hypotonic lysis, and the remaining cells were suspended in 0.1% BSA in PBS prior to determination of total cell number and preparation of cytospin slides.

2.3 Cytokines in serum and cell culture supernatants

Bone marrow eosinophil culture supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C prior to use. Macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) were evaluated by ELISA (R&D). Mouse cytokines evaluated by multibead assay (Bio-Rad) included: IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, -3, -4, -5, -6, -9, and -10, IL-12(p40), IL-12(p70), IL-13, IL-17A, eotaxin-1/CCL11, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFNγ, KC, MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES/CCL5 and TNFα.

2.4 In vitro culture of eosinophils

The method for eosinophil culture from unselected bone marrow progenitors was as previously described [3]. Briefly, the femur and tibia were flushed with RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), the red blood cells were lysed, and the remaining cells were suspended RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen). The cells were seeded at 106/mL in 10 – 15 mL media containing RPMI 1640 with 20% FBS (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ), 100 IU/mL penicillin and 10 μg/mL streptomycin (Cellgro Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA), 2 mM glutamine (Invitrogen), 25 mM HEPES, 1x non-essential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen) and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), supplemented with 100 ng/mL stem-cell factor (SCF; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and 100 ng/mL Flt3L (PeproTech); cells were maintained in this medium from day 0 to day 4. On day 4, the medium containing SCF and Flt3L was replaced with fresh medium containing 10 ng/mL recombinant mouse interleukin-5 (IL-5), 10 ng/mL recombinant mouse interleukin-33 (IL-33) or a combination of the two cytokines (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). One-half of the media was replaced with fresh cytokine-containing media every other day. On day 8 the flask containing the cells was changed. In experiments in which IL-5 was supplemented with M-CSF or GM-CSF (R&D), these cytokines were used at 1 ng/ml. In experiments involving the neutralizing rat monoclonal anti-M-CSF or anti-GM-CSF antibodies and isotype controls (R&D), these reagents were added to a final concentration of 5μg/ml from day 4 of culture onward. The total cell number and percent eosinophils was determined in both suspension and adherent cultures as indicated.

2.5 Flow cytometric analysis

Bone marrow cells were suspended in 0.1% BSA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in PBS and probed with fluorescent-tagged antibody or isotype control. Each antibody was used in the presence of 0.5 μg blocking antibody, anti-CD16/CD32 (clone 2.4G2, BD Pharmingen) and Live-Dead stain (Invitrogen) and incubated for 1 hour at 4°C in the dark. After washing in 0.1% BSA in PBS, 100,000 events were collected on a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and the data was analyzed in FlowJo 7.5 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). Compensation was performed in FlowJo post-collection. All analyses were performed on cells within the live gate and the data are reported as percentage of live cells. Antibodies recognizing Siglec F (BD Pharmingen #552126) and recommended isotype control (rat IgG2aK #553930) were used.

2.6 Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Each dataset was examined by ANOVA followed by either Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison post-test or as indicated in the figure legends.

3. Results

3.1. Systemic interleukin-33 (IL-33) elicits eosinophilia in vivo

Previous studies focused on IL-33 and its receptor, ST2/IL1RL1 documented a role for this cytokine-signaling pathway in promoting synthesis and release of Th2 cytokines, resulting in blood and tissue eosinophilia [16,23]. Systemic administration of IL-33 (0.1 μg IL-33 per BALB/c mouse per day for 7 days) resulted in increased serum levels of the Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 (Figure 1A). Total cells in the bone marrow increased from 2.3 to 4.0 × 107 cells/mouse (Figure 1B) in association with a dramatic increase in percent eosinophils (5% to nearly 80%), identified with Diff-Quik stain (Figure 1C) and by flow cytometry with anti-Siglec F antibody (Figure 1D). Profound eosinophil accumulation was also noted in the peritoneal cavity and in the spleen (data not shown). IL-33 was unable to circumvent eosinophil deficiency secondary to the ΔdblGATA deletion (Figure 1C and 1D), although previous studies indicate that there are conditions under which this is possible [24]. IL-33 was also unable to induce eosinophilia in IL-5−/− mice (Figure 1C and 1D) confirming the IL-5 dependence of this response.

Figure 1. Administration of IL-33 alters Th2 serum cytokine levels in mice and promotes bone marrow eosinophilia.

Mice received IL-33 (0.1 μg/day for 7 days) via intraperitoneal injection (closed symbols) or were left untreated (open symbols); serum was collected from individual BALB/c mice on day 8; bone marrow was collected on day 9 from wild-type BALB/c, eosinophil-deficient ΔdblGATA, and interleukin-5 gene-deleted mice. (A) Serum levels of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13; n = 5 – 14 mice per group. Groups were compared with the Mann-Whitney test, **p < 0.01. (B) Total number of bone marrow cells recovered from each mouse; (C) Percent eosinophils were determined by counting of Diff-Quik stained cells recovered from the bone marrow; (D) Cell surface expression of Siglec F was evaluated by flow cytometry. Each symbol represents data derived from a single mouse. Groups were compared with ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post-test, *** p < 0.001.

3.2. IL-33 antagonizes IL-5-mediated eosinophil differentiation

Our protocol for generating phenotypically and functionally mature eosinophils ex vivo depends directly on the actions of IL-5 [3]. As shown in Figure 2, IL-33 initially promotes proliferation of the SCF and Flt3L-stimulated progenitors, but ultimately redirects IL-5-mediated eosinophil differentiation. Cells cultured in IL-33 alone or in IL-33 together with IL-5 from day 4 forward proliferate dramatically up to day 8, after which the population of cells in suspension undergoes rapid decline (Figure 2A). IL-33 alone does not support the differentiation of progenitors into eosinophils, and actually antagonizes the effects of IL-5 (Figure 2B). While the cells cultured with IL-5 alone remain predominantly in suspension and acquire eosinophilic characteristics (Figure 2C), there are relatively few eosinophils among the cells in suspension that include IL-33. Most of cells in cultures that include IL-33 become adherent, and acquire a macrophage-like phenotype (Figure 2D and 2E). The percent eosinophils in suspension and among the adherent cell populations in each culture condition (measured as Siglec F+ cells) are as indicated in Figure 2F; very few (< 5%) are Siglec F+, and most are F4/80+ (data not shown) as would be anticipated for bone marrow-derived macrophages. Even at peak cell population (day 8, Fig. 2A), cultures that include IL-33 alone generate comparatively few total eosinophils (Table 1, Supplemental Figure 1). Cultures that include both IL5 and IL-33 generate 3-fold fewer total eosinophils than cultures with IL-5 alone, documenting clearly both the antagonistic effect and the dominance of IL-33 in this culture system.

Figure 2. IL-33 antagonizes IL-5-mediated eosinophil hematopoiesis ex vivo.

Bone marrow cells were cultured for 4 days in stem cell factor (SCF) and Flt3 ligand (Flt3L), then transferred into media containing IL-5, IL-33 or the combination of IL-5 + IL-33. (A) Total number of cells in suspension at various time points, day 4 and onward, n = 3 – 6 cultures from individual mice per time point. (B) Percentage eosinophils at each time point; groups were compared by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post-test, *** p < 0.001, representative experiment from a total of 4. (C – E) Cells fixed and stained with Diff-Quik; shown are cells in suspension (Su) from cultures transferred to IL-5; those in suspension from cultures transferred to IL-33; and cells adherent to the culture flask from cultures transferred to IL-33, all at day 8. Original magnification was 63x. (F) Expression of Siglec F at day 8 on suspension cells (Su) and adherent cells (Ad) as indicated. Groups compared with ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post-test, **** p<0.0001.

Table 1. IL-33 antagonizes eosinophil hematopoiesis promoted by IL-5.

The total and percent eosinophils among cells in suspension and adherent to the culture flask at day 8 of culture were determined by Diff-Quik stain.

| Cultures Differentiated with: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-5 | IL-33 | IL-5 + IL-33 | |

| # cells in suspension (× 106) | 2.83 ± 0.3 | 7.6 ± 0.2 | 8.9 ± 0.7 |

| % eosinophils | 41.7 ± 1.8 | 0.95 ± 0.39 | 3.92 ± 1.02 |

| Total eosinophils in suspension (× 106) | 1.16 ± 4.6** | 0.07 ± 0.29 | 0.34 ± 1.4 |

| # adherent cells (× 106) | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 1.34 ± 0.16 | 1.25 ± 0.25 |

| % eosinophils | 4.0 ± 1.6 | 0.5 ± 0.29 | 1.08 ± 0.47 |

| Total adherent eosinophils (× 106) | 0.01 ± .01 | 0.01 ± .01 | 0.01 ± .01 |

| Total eosinophils in culture (× 106) | 1.17 ± .17** | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.35 ± .09 |

| Fold reduction in total eosinophils | - | 14.6 | 3.3 |

p < 0.01 by 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post-test.

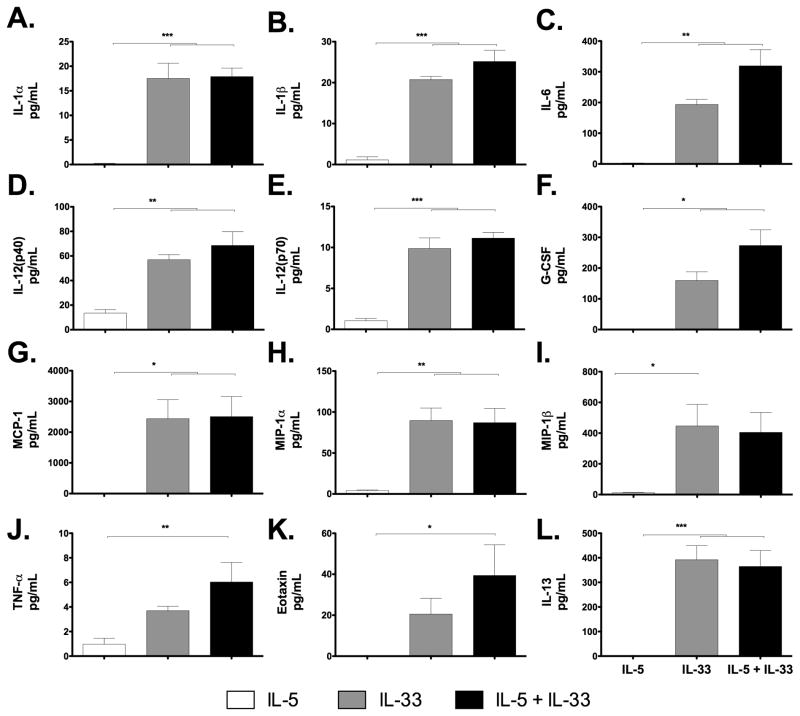

3.3. Cytokines Detected in Bone Marrow Culture

Numerous cytokines were detected in SCF and FLt3L-primed bone marrow progenitor cultures differentiated with IL-33 either alone or IL-33 with IL-5 (Figure 3). Interestingly, many of these cytokines are among those characterized as products of monocytes and macrophages [25–28]. However, none of these are unique lineage markers, and several are also eosinophil secretory mediators [3,29]. IL-10 and RANTES were the only mediators on the panel that were detected under all conditions utilized (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 3. Detection of cytokines in bone marrow progenitor cultures.

Culture supernatants were collected at day 8 and evaluated for the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Cultures with IL-5 only open bar; with IL-33 only, grey bars; with IL-5 + IL-33, black bars. Cytokines detected include: (A) IL-1α, (B) IL-1β, (C) IL-6, (D) IL-12p40, (E) IL-12p70, (F) G-CSF, (G) MCP-1, (H) MIP-1α, (I) MIP-1β (J) TNF-α (K) eotaxin-1 and (L) IL-13. Groups were compared by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, *** p<0.001; Data pooled from two experiments, n = 7 mice per data point.

3.4 GM-CSF contributes to the IL-33-mediated antagonism of IL-5

In order to explore the mechanisms via which IL-33 antagonizes IL-5 and induces macrophage development, we first examined the expression of macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in culture media collected from bone marrow cells differentiated in the presence of IL-5 and IL-33. We found that both M-CSF (Figure 4A) and GM-CSF (Figure 4B) could be detected in supernatants from cells in culture with IL-33. Expression of GM-CSF was low (< 10 pg/ml) and transient while the expression of M-CSF was more robust and sustained. We found that supplementation of SCF and Flt3L-primed progenitors grown in IL-5 with 1 ng/ml GM-CSF resulted in a drop in the percentage of eosinophils (from 97% to 24% when evaluated on day 12) although not to the level detected when cells were cultured in IL-5 and IL-33 (Figure 4C). In contrast, addition of M-CSF (1 ng/mL) to SCF and Flt3L-primed progenitors grown in IL-5 (with or without GM-CSF) had no effect on percentage eosinophils achieved. These results suggest that M-CSF was not contributing to the IL-33-mediated inhibition of eosinophil differentiation. Likewise, antibody-mediated neutralization of GM-CSF in cultures differentiated with both IL-5 and IL-33 resulted in a partial recovery of eosinophil hematopoiesis when compared to cultures provided with an equivalent amount of isotype control (Figure 4D). Neutralizing antibody directed against M-CSF had no impact on eosinophil hematopoiesis in these experiments.

Figure 4. GM-CSF but not M-CSF partially mediates the antagonistic effects of IL-33 on IL-5 dependent eosinophil differentiation.

Cells were cultured as indicated and cell supernatants were collected and assayed by ELISA for the presence of: (A) M-CSF or (B) GM-CSF. (C) IL-5 (10 ng/ml) was supplemented with IL-33, M-CSF or GM-CSF or the combination of M-CSF and GM-CSF; percent eosinophils was determined on day 12 of culture. (D) Antibodies (5 μg/ml) directed against either M-CSF or GM-CSF or isotype controls (IgG2a for anti-GM-CSF antibody and IgG2b for anti-M-CSF antibody) were added to IL5 + IL-33 supplemented cultures and the percent eosinophils was determined on day 11 of culture. Groups were compared with unpaired t-test, ns = not significant; *** p<0.001, n = 4 – 7 mice per group.

4. Discussion

Among our findings, we confirmed that IL-33 administered systemically elicited profound IL-5-dependent eosinophilia [16]. Recent studies indicate that IL-33 elicits IL-5 production from sources other than traditional Th2 lymphocytes. Among these, Neill and colleagues [14] have described nuocytes, distinct non-T non-B innate effector cells. Likewise, Ikutani and colleagues [30] have defined a distinct population of innate non-T IL-5 producing cells that are crucial for promoting eosinophil recruitment to the lung tissue specifically in response to IL-33.

As IL-33 elicits eosinophilia, albeit indirectly via IL-5, and serves to activate peripheral blood eosinophils [11], our initial intent was to examine eosinophil hematopoiesis in direct response to IL-33. Stolarski and colleagues [31] examined this question, and found that c-kit (CD117, also known as the SCF receptor) - positive mouse bone marrow progenitors generated 10% eosinophils by day 5 in culture in response to either IL-5 or IL-33 alone. In contrast, we found that unselected bone marrow progenitors initially primed with SCF and Flt3L responded somewhat differently, with IL-33 antagonizing eosinophil-hematopoiesis promoted by IL-5. We include Flt3L and SCF in our culture system, as they are factors that sustain murine progenitors and promote hematopoiesis. SCF-mediated signaling through c-Kit/CD117 is absolutely crucial for normal hematopoiesis [32] and Flt3L, while dispensable for maintaining progenitors pre-transplantation [33], synergizes with SCF and promotes the growth of murine stem cells ex vivo [34]. As a result, we typically achieve 100 % eosinophils from SCF and Flt3L primed unselected progenitors from BALB/c mice cultured with IL-5 in conjunction with a 3 -10 fold increase in total cell number. In contrast, Ishihara and colleagues [35] found that IL-5 alone without SCF and Flt3L generated eosinophils from rat bone marrow progenitors ex vivo, but the cultures sustained an overall four-fold drop in cell number.

We were initially surprised to find that the addition of IL-33 to primed progenitors generated predominantly a macrophage-like phenotype, and even more so, that IL-33 would antagonize the IL-5 dependent eosinophil hematopoiesis. Several groups have reported IL-33-dependent differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors into other myeloid lineages [12,36] including dendritic cells (DCs [37]). Interestingly, IL-33-mediated generation of CD11c+ DCs was completely blocked by anti-GM-CSF, and was associated with no detectable levels of IL-12p70, in contrast to the findings presented here (Figure 3). In other studies, IL-33 has been implicated prominently as a factor promoting M1/M2 polarization and augmented inflammatory capacity [38–42]. At current writing, nuocytes are the only cells known to require IL-33 for development from progenitors in vitro [43].

5. Conclusions

In summary, we note a profound distinction between the outcome of IL-33 administration in vivo and the actions of IL-33 directed at SCF and Flt3L-primed bone marrow progenitors in culture. In vivo, IL-33 elicits the production of IL-5 leading to systemic eosinophilia. In contrast, IL-33 does not serve as a strong promoter of eosinophil growth and differentiation in an IL-5-dependent bone marrow culture system, but instead antagonizes the growth and differentiation of progenitors promoted, at least in part, via the actions of GM-CSF.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

IL-33 mediated eosinophil hematopoiesis is IL-5 dependent in vivo

IL-33 antagonizes the effects of IL-5 in vitro and inhibits IL-5 dependent eosinophil differentiation

The autocrine release of GM-CSF in IL-33 treated cultures mediates, in part, the IL-33 inhibition of IL-5 dependent eosinophil differentiation

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Paul S. Foster, University of Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia, for providing the IL-5 gene-deleted mice on the BALB/c background, Dr. Ricardo Dreyfuss for preparing the photomicrographs, and Dr. Alfonso Gozalo (CMB/NIAID) and his staff at the 14BS animal facility for care of the mice used in this work. This work is supported by NIAID DIR funding #AI000941 to HFR.

Footnotes

Authorship and Conflict of Interest Statements

Kimberly D. Dyer conceived and performed the experiments and prepared the manuscript. KDD declares that there are no competing financial interests.

Caroline M. Percopo provided technical assistance and provided editorial advice on final draft of paper. CMP declares that there are no competing financial interests.

Helene F. Rosenberg provided oversight on the design and execution of the project and preparation of manuscript. HFR declares that there are no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Takatsu K, Nakajima H. IL-5 and eosinophilia. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roboz GJ, Rafii S. Interleukin-5 and the regulation of eosinophil production. Curr Opin Hematol. 1999;6:164–168. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199905000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyer KD, Moser JM, Czapiga M, Siegel SJ, Percopo CM, Rosenberg HF. Functionally competent eosinophils differentiated ex vivo in high purity from normal mouse bone marrow. Journal of Immunology. 2008;181:4004–4009. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurowska-Stolarska M, Hueber A, Stolarski B, McInnes IB. Interleukin-33: a novel mediator with a role in distinct disease pathologies. J Intern Med. 2011;269:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moussion C, Ortega N, Girard JP. The IL-1-like cytokine IL-33 is constitutively expressed in the nucleus of endothelial cells and epithelial cells in vivo: a novel ‘alarmin’? PLoS One. 2008;3:e3331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanada S, Hakuno D, Higgins LJ, Schreiter ER, McKenzie AN, Lee RT. IL-33 and ST2 comprise a critical biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1538–1549. doi: 10.1172/JCI30634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood IS, Wang B, Trayhurn P. IL-33, a recently identified interleukin-1 gene family member, is expressed in human adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;384:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kouzaki H, Iijima K, Kobayashi T, O’Grady SM, Kita H. The danger signal, extracellular ATP, is a sensor for an airborne allergen and triggers IL-33 release and innate Th2-type responses. J Immunol. 2011;186:4375–4387. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurowska-Stolarska M, Kewin P, Murphy G, Russo RC, Stolarski B, Garcia CC, et al. IL-33 induces antigen-specific IL-5+ T cells and promotes allergic-induced airway inflammation independent of IL-4. J Immunol. 2008;181:4780–4790. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzukawa M, Iikura M, Koketsu R, Nagase H, Tamura C, Komiya A, et al. An IL-1 cytokine member, IL-33, induces human basophil activation via its ST2 receptor. Journal of Immunology. 2008;181:5981–5989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherry WB, Yoon J, Bartemes KR, Iijima K, Kita H. A novel IL-1 family cytokine, IL-33, potently activates human eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1484–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allakhverdi Z, Smith DE, Comeau MR, Delespesse G. Cutting edge: The ST2 ligand IL-33 potently activates and drives maturation of human mast cells. Journal of Immunology. 2007;179:2051–2054. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moro K, Yamada T, Tanabe M, Takeuchi T, Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, et al. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature. 2010;463:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TK, et al. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367–1370. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brickshawana A, Shapiro VS, Kita H, Pease LR. Lineage-Sca1+c-Kit-CD25+ Cells Are IL-33-Responsive Type 2 Innate Cells in the Mouse Bone Marrow. Journal of Immunology. 2011;187:5795–5804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow JY, Wong CK, Cheung PF, Lam CW. Intracellular signaling mechanisms regulating the activation of human eosinophils by the novel Th2 cytokine IL-33: implications for allergic inflammation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2010;7:26–34. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzukawa M, Koketsu R, Iikura M, Nakae S, Matsumoto K, Nagase H, et al. Interleukin-33 enhances adhesion, CD11b expression and survival in human eosinophils. Lab Invest. 2008;88:1245–1253. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Na HJ, Hudson SA, Bochner BS. IL-33 enhances Siglec-8 mediated apoptosis of human eosinophils. Cytokine. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kopf M, Brombacher F, Hodgkin PD, Ramsay AJ, Milbourne EA, Dai WJ, et al. IL-5-deficient mice have a developmental defect in CD5+ B-1 cells and lack eosinophilia but have normal antibody and cytotoxic T cell responses. Immunity. 1996;4:15–24. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu C, Cantor AB, Yang H, Browne C, Wells RA, Fujiwara Y, et al. Targeted deletion of a high-affinity GATA-binding site in the GATA-1 promoter leads to selective loss of the eosinophil lineage in vivo. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1387–1395. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dyer KD, Garcia-Crespo KE, Killoran KE, Rosenberg HF. Antigen profiles for the quantitative assessment of eosinophils in mouse tissues by flow cytometry. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2011;369:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohto-Ozaki H, Kuroiwa K, Mato N, Matsuyama Y, Hayakawa M, Tamemoto H, et al. Characterization of ST2 transgenic mice with resistance to IL-33. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2632–2642. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyer KD, Czapiga M, Foster B, Foster PS, Kang EM, Lappas CM, et al. Eosinophils from lineage-ablated Delta dblGATA bone marrow progenitors: the dblGATA enhancer in the promoter of GATA-1 is not essential for differentiation ex vivo. Journal of Immunology. 2007;179:1693–1699. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavaillon JM. Cytokines and macrophages. Biomed Pharmacother. 1994;48:445–453. doi: 10.1016/0753-3322(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menten P, Wuyts A, Van Damme J. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2002;13:455–481. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(02)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Netea MG, Demacker PN, Kullberg BJ, Boerman OC, Verschueren I, Stalenhoef AF, et al. Increased interleukin-1alpha and interleukin-1beta production by macrophages of low-density lipoprotein receptor knock-out mice stimulated with lipopolysaccharide is CD11c/CD18-receptor mediated. Immunology. 1998;95:466–472. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soehnlein O, Lindbom L. Phagocyte partnership during the onset and resolution of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:427–439. doi: 10.1038/nri2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg HF, Dyer KD, Foster PS. Eosinophils: changing perspectives in health and disease. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nri3341. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikutani M, Yanagibashi T, Ogasawara M, Tsuneyama K, Yamamoto S, Hattori Y, et al. Identification of Innate IL-5-Producing Cells and Their Role in Lung Eosinophil Regulation and Antitumor Immunity. Journal of Immunology. 2012;188:703–713. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stolarski B, Kurowska-Stolarska M, Kewin P, Xu D, Liew FY. IL-33 exacerbates eosinophil-mediated airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;185:3472–3480. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edling CE, Hallberg B. c-Kit--a hematopoietic cell essential receptor tyrosine kinase. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2007;39:1995–1998. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buza-Vidas N, Cheng M, Duarte S, Charoudeh HN, Jacobsen SE, Sitnicka E. FLT3 receptor and ligand are dispensable for maintenance and posttransplantation expansion of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2009;113:3453–3460. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hudak S, Hunte B, Culpepper J, Menon S, Hannum C, Thompson-Snipes L, et al. FLT3/FLK2 ligand promotes the growth of murine stem cells and the expansion of colony-forming cells and spleen colony-forming units. Blood. 1995;85:2747–2755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishihara K, Satoh I, Mue S, Ohuchi K. Generation of rat eosinophils by recombinant rat interleukin-5 in vitro and in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1501:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider E, Petit-Bertron AF, Bricard R, Levasseur M, Ramadan A, Girard JP, et al. IL-33 activates unprimed murine basophils directly in vitro and induces their in vivo expansion indirectly by promoting hematopoietic growth factor production. J Immunol. 2009;183:3591–3597. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayuzumi N, Matsushima H, Takashima A. IL-33 promotes DC development in BM culture by triggering GM-CSF production. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:3331–3342. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Espinassous Q, Garcia-de-Paco E, Garcia-Verdugo I, Synguelakis M, von Aulock S, Sallenave JM, et al. IL-33 enhances lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory cytokine production from mouse macrophages by regulating lipopolysaccharide receptor complex. J Immunol. 2009;183:1446–1455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joshi AD, Oak SR, Hartigan AJ, Finn WG, Kunkel SL, Duffy KE, et al. Interleukin-33 contributes to both M1 and M2 chemokine marker expression in human macrophages. BMC Immunol. 2010;11:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-11-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurowska-Stolarska M, Stolarski B, Kewin P, Murphy G, Corrigan CJ, Ying S, et al. IL-33 amplifies the polarization of alternatively activated macrophages that contribute to airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;183:6469–6477. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohno T, Oboki K, Morita H, Kajiwara N, Arae K, Tanaka S, et al. Paracrine IL-33 stimulation enhances lipopolysaccharide-mediated macrophage activation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zaiss MM, Kurowska-Stolarska M, Bohm C, Gary R, Scholtysek C, Stolarski B, et al. IL-33 shifts the balance from osteoclast to alternatively activated macrophage differentiation and protects from TNF-alpha-mediated bone loss. J Immunol. 2011;186:6097–6105. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barlow JL, Bellosi A, Hardman CS, Drynan LF, Wong SH, Cruickshank JP, et al. Innate IL-13-producing nuocytes arise during allergic lung inflammation and contribute to airways hyperreactivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.