Abstract

Neuroendocrine abnormalities, such as activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, are associated with obesity; however, few large-scale population-based studies have examined HPA axis and markers of obesity. We examined the cross-sectional association of the cortisol awakening response (CAR) and diurnal salivary cortisol curve with obesity. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Stress Study includes 1,002 White, Hispanic, and Black men and women (mean age 65±9.8 years) who collected up to 18 salivary cortisol samples over 3 days. Cortisol profiles were modeled using regression spline models that incorporated random parameters for subject-specific effects. Cortisol curve measures included awakening cortisol, CAR (awakening to 30 minutes post-awakening), early decline (30 minutes to 2 hours post-awakening), late decline (2 hours post-awakening to bedtime), and the corresponding areas under the curve (AUC). Body-mass-index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC) were used to estimate adiposity. For the entire cohort, both BMI and WC were negatively correlated with awakening cortisol (p<0.05), AUC during awakening rise and early decline and positively correlated to the early decline slope (p<0.05) after adjustments for age, race/ethnicity, gender, diabetes status, socioeconomic status, beta blockers, steroids, hormone replacement therapy and smoking status. No heterogeneities of effects were observed by gender, age, and race/ethnicity. Higher BMI and WC are associated with neuroendocrine dysregulation, which is present in a large population sample, and only partially explained by other covariates.

Keywords: adiposity, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, salivary cortisol, diurnal cortisol, cortisol awakening response, epidemiology, obesity, body mass index, waist circumference, epidemiology

HPA axis dysfunction is associated with obesity and the metabolic syndrome(1). Greater adrenocorticotropin hormone responses to stimulatory testing have been observed in subjects with higher waist-to-hip ratios (WHR)(2) or higher body mass index (BMI)(3). Other studies have suggested that higher WHR or abdominal sagittal diameter is associated with blunted dexamethasone suppression of cortisol (4), higher cortisol awakening response (CAR)(5), higher serum cortisol during stress(6), and lower awakening cortisol levels (7-9). Higher BMI has been found to be associated with lower morning cortisol(10); however, higher urine free cortisol (UFC) has been positively associated with WHR(2, 11), subcutaneous adipose tissue(12), BMI(13), visceral fat area by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)(14), and the presence of metabolic syndrome(15). Purnell et al found increased cortisol production rate and free cortisol levels to be associated with higher intraabdominal fat via computed tomography (CT)(16).

In contrast, other studies have reported conflicting results. Some analyses of small studies have described no correlations between UFC and visceral fat as measured by CT (17) and WHR (7, 17, 18). Other studies have shown no association between WHR and dexamethasone suppressed cortisol levels (7, 11), and in one study, higher BMI actually associated with lower dexamethasone suppressed cortisol levels (13).

Studies of the association of the diurnal cortisol profile with anthropometry measures of adiposity have shown mixed results. Higher WHR has been associated with lower diurnal cortisol variability (19, 20), and lower cortisol levels (21). While CAR has been positively associated with WHR (5) and WC (22), others found an inverse association between awakening or morning cortisols and BMI (23, 24). Kumari M et al noted from a large population based study that the most flat diurnal salivary cortisol slopes were observed among individuals with the highest and lowest BMI and WC, possibly explaining the mixed findings in other studies (24). With the exception of two large studies (23, 24), studies to date have been limited by small sample size, single gender, and/or single race/ethnicity. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Stress Study collected diurnal salivary cortisol profiles on a subset of 1,002 ethnically diverse adult men and women and offered a unique opportunity to examine the association of the HPA axis profile with BMI (as a marker of overall adiposity) and WC (as a marker of central adiposity). MESA is unique from other studies in having detailed salivary cortisol collection (8 time points/day over 3 days) to permit examination of multiple components of the diurnal cortisol curve with body fat measures. We were also unique in being able to exploit additional data collected from the main MESA study to examine potential confounders/explanatory factors in these associations. Based on prior reported studies, we hypothesized that lower diurnal cortisol variability, higher CAR, and higher cortisol area under curve (AUC) as a marker of cortisol production would be associated with higher BMI and WC.

METHODS

Study Population

MESA is a multi-center longitudinal cohort study of the prevalence and correlates of subclinical cardiovascular disease and the factors that influence its progression (25). Individuals were not eligible to participate in MESA if they had clinical cardiovascular disease at baseline(25). Between July 2000 and August 2002, 6814 men and women who identified themselves as white, black, Hispanic, or Chinese, and were 45 to 84 years of age were enrolled from six different US communities. Details on the sampling frames and the cohort examination procedures are published (25).

Between July 2004 and November 2006, in conjunction with the second and third follow-up examinations of the full MESA sample, a subsample of 1002 white, Hispanic, and African-American participants from either Los Angeles County, California or Northern Manhattan and the Bronx, New York participated in a sub-study of biological stress markers (the MESA Stress Study), which included repeat assessments of salivary cortisol (26). Enrollment continued until approximately 500 participants were enrolled at each site. Informed consent was obtained from each participant, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each institution.

Hormonal Measures

MESA Stress Study participants were instructed, by trained staff, to collect six salivary cortisol samples a day (directly upon awakening, 30 minutes after waking, 10:00 am, 12:00 pm or before lunch whichever was earlier, 6:00 pm or before dinner whichever was earlier, and at bedtime). Salivary cortisol measures free as opposed to bound cortisol, thus, it is less prone to variability due to changes in cortisol binding proteins (i.e. corticotrophin binding globulin and albumin) and is the preferred method of measurement for dynamic HPA axis studies (27). This daily collection protocol was repeated on each of three successive week days; thus, each participant provided up to 18 cortisol measures. Participants recorded collection time on special cards; in addition, a time tracking device (Track Caps) automatically registered the time at which cotton swabs were extracted to collect each sample. Participants were told of this time tracking device.

Saliva samples were collected using cotton swabs and stored at −20 C until analysis. Before biochemical analysis, samples were thawed and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 3 minutes to obtain clear saliva with low viscosity. Cortisol levels were determined employing a commercially available chemi-luminescence assay (CLIA) with a high sensitivity of 0.16 ng/ml (IBL-Hamburg; Germany). Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation are below 8%. For our analyses, all cortisol measures at each time over 3 days were treated as repeated measures and not averaged. Awakening cortisol was defined as the salivary cortisol obtained at time zero. Cortisol awakening response (CAR) rise was the cortisol rise from time zero to 30 minutes post-awakening. Early decline in cortisol (CAR decline) was defined as 30 minutes post-awakening to 2 hours post-awakening. Late decline in cortisol was from 2 hours post-awakening to bedtime (26). A few unusually high salivary cortisol values were noted which did not seem physiologically plausible, and 20 such values were excluded based on being inappropriately high compared to other values for that time of day within the same subject.

Assessment of BMI, Waist Circumference, and Obesity

Weight and height were measured using a balanced beam scale and a vertical ruler, respectively, with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes. Height was recorded to the nearest 0.5 cm and weight to the nearest 0.5 lb. Body-mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). BMI categories are as defined by the World Health Organization (1995) as normal (<25 kg/m2), grade 1 overweight (25-30 kg/m2), grade 2 overweight (30-40 kg/m2), and grade 3 overweight (>40 kg/ m2)(28). Waist circumference (WC) was measured at the minimum abdominal girth. All anthropometric measures were taken in duplicate and averaged.

Covariates

Data on age, race/ethnicity, sex, years of education, cigarette smoking, highest level of education achieved, and annual income by self-report using standard protocols previously described (25). Analysis of socioeconomic status was simplified by use of a single wealth-income index variable described by Hajat A et al (29). This wealth-income index is a composite socioeconomic status measure that incorporates annual income and information about assets. Prescription and over-the-counter medications were determined by transcription of medications brought into clinic during each exam (25). Smoking was assessed by self-report and categorized according to current, ever, and never smokers. Because Badrick E et al (30) showed higher salivary cortisol levels in current smokers only and no differences among ex-smokers and never-smokers, we accounted for smoking by current smoking or non-current smoking status. Diabetes status was defined according to the 2003 American Diabetes Association criteria as fasting glucose >7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or use of hypoglycemic medication (oral agents and/or insulin). Impaired fasting glucose was defined as a fasting glucose of 5.5 to 6.9 mmol/L (100 to 125 mg/dL)(31).

Statistical Analysis

Analysis Overview

In each of our analyses, we determined the association of cortisol curve parameters with BMI and WC. For the purpose of our analyses, we have defined our exposure variable as the cortisol measurements and our outcome variables as BMI and WC. Cortisol distribution was log-transformed due to skewed distributions. BMI was maintained as a continuous variable in some analyses and a categorical variable in others. Because only 49 participants met criteria for the grade 3 overweight category, our analyses combined the grade 2 and grade 3 overweight groups. Specific details of our analyses are summarized below but in general, the regression coefficients derived from our linear regression models represent the change in BMI (kg/m2) or WC (cm) per one unit increase in the log of the cortisol variable. In the case of categorical BMI, the regression coefficients represent the mean difference in the log of the cortisol variable in individuals in the overweight categories compared with normal weight individuals (reference category). Because of significant differences seen in cortisol according to diabetes status in prior MESA analyses (32), secondary analyses were performed excluding individuals with diabetes or impaired fasting glucose.

In the base model for these analyses, adjustments were made for age, race/ethnicity, gender, and diabetes status. To explore potential confounding or explanatory factors in our associations, we performed the following additional multivariable adjustments: wealth-income index (socioeconomic status marker), current smoking status, and medications that have the potential to affect cortisol, namely beta-blockers, steroids, and hormone replacement therapy (33). Adjustments for wake up time were made.

Derivation of Salivary Cortisol Curve Variables

Cortisol secretion has a well-documented circadian pattern typified by a rapid early morning peak within 30 to 45 minutes after waking followed by a decline throughout the remainder of the day (26). To capture all the relevant inflections of the circadian rhythm, we modeled our data utilizing the approach of Ranjit N et al (26). Daily cortisol values were modeled as a function of time since wake up, using linear regression mixed model splines with “knots” located to capture the ascending and descending phases of the CAR and the slower decline over the course of the remainder of the day. Knots were located at 30 and 120 minutes after wake up based on prior MESA analyses (26). The choice of the two knots was confirmed by the LOESS curve on the diurnal cortisol level. The presence of the knots allowed the relationship between time after wake up and cortisol levels (i.e. slope associated with time) to vary over the day.

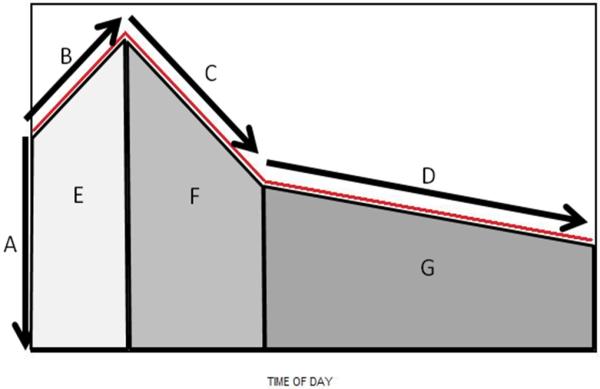

Similar to Ranjit N et al., we obtained the key parameters of the spline models: the intercept (mean cortisol value at time 0 or at wake time, called “awakening cortisol”), the slope in cortisol from wake time to 30 minutes post-awakening (the rapidly changing ascending CAR slope, called CAR), the slope in cortisol from 30 minutes to 120 minutes post-awakening (the rapidly descending CAR slope, called “early decline”), and the slope in cortisol from 120 minutes post-awakening to bedtime, called “late decline” (26). This is depicted in an exaggerated version of a diurnal cortisol curve in Figure 1. By including covariates in the model as main effects and in interaction with the different slope parameters, we were able to estimate how these parameters varied as a function of BMI, after adjusting for other risk factors and/or confounders (26).

Figure 1.

Summary of Diurnal Cortisol Curve Parameters Derived from Mixed Model Linear Regression

Key: A=awakening cortisol at time zero; B=cortisol awakening response (CAR) denoting rise from awakening to 30 minutes post-awakening; C=early decline from 30 minutes post-awakening to 2 hours post-awakening; D=late decline from 2 hours post-awakening to bedtime; E=area under curve (AUC) for CAR; F=AUC for early decline; G=AUC for late decline; the full AUC is the sum E+F+G

We used mixed model linear regression to account for within-subject correlation between repeated measures as well as a variable number of repeated measures within a person and variations in the times of sample collection, as done previously (26). To account for correlations, the intercept and the time slope parameters for each person were treated as random, and an unstructured covariance matrix was used to obtain robust standard errors. All covariates were treated as fixed effects.

We also calculated area under the curve (AUC) summary measures to estimate the total amount of cortisol exposure during the portions of the diurnal cortisol cycle outlined above. Based on the constructed spline model, we calculated several adjusted AUC summary measures by BMI and WC, including the full AUC (awakening to bedtime), CAR AUC (awakening to 30 minutes), early decline AUC (30 minutes to 2 hours), and late decline AUC (2 hours to bedtime) (Figure 1). For the purpose of this analysis, bedtime is defined as 16 hours post-awakening (29).

In all of our analyses, a two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.2.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1 stratified by BMI category. Age and education were inversely associated with weight status, whereas African-American or Hispanic race, female sex, waist circumference, and prevalence of glucose disorders were positively associated with weight status. Income, depressive symptoms, and smoking status were not related to obesity. There were some individuals taking medications that might confound the association between hormonal measures and BMI or WC (33), including 10 on oral steroids, 27 on inhaled steroids, 71 on hormone replacement therapy, and 346 on beta blockers. Among those with normal BMI, there were only 4 individuals with BMI<18 kg/m2.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Population

| Variable | Category | BMI Category | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (n=233) |

Grade 1 overweight (n=413) |

Grade 2&3 overweight (n=355) |

|||

| Age (Mean (std)) | 66.4 (10.4) | 66.0 (10.0) | 63.8 (8.9) | 0.0014a | |

| Adjusted income wealth index(Mean (std)) |

4.13 (2.29) | 3.73 (2.33) | 3.59 (2.27) | 0.020a | |

| Mean waist circumference (cm) (Mean (std)) |

85.4 (7.6) | 96.9 (7.2) | 111.3 (9.2) | <0.0001b | |

| Gender | Male | 48.5% | 54.7% | 38.3% | <0.0001b |

| Female | 51.5% | 45.3% | 61.7% | ||

| Race/ethnicity | Caucasian | 32.2% | 17.9% | 11.0% | <0.0001b |

| African-American | 25.8% | 24.7% | 34.9% | ||

| Hispanic | 42.0% | 57.4% | 54.1% | ||

| Diabetes status | Normal | 78.1% | 62.7% | 49.0% | <0.0001b |

| Impaired fasting glucose | 14.6% | 21.3% | 24.8% | ||

| Diabetes | 7.3% | 16.0% | 26.2% | ||

| Elevated depressive symptom status |

CES-D<16c | 81.9% | 82.1% | 79.4% | 0.595 |

| CES-D>16c | 18.1% | 17.9% | 20.6% | ||

| Education | < High school | 18.9% | 30.8% | 27.6% | 0.013a |

| High school | 20.2% | 18.6% | 22.0% | ||

| ≥ College | 60.9% | 50.6% | 50.4% | ||

| Income | <$16,000 | 21.4% | 24.8% | 25.6% | 0.552 |

| $16,000-$24,999 | 14.3% | 15.6% | 15.2% | ||

| $25,000-$34,999 | 15.6% | 17.6% | 18.7% | ||

| $35,000-$49,999 | 15.6% | 15.6% | 15.2% | ||

| $50,000-$74,999 | 13.8% | 11.2% | 13.8% | ||

| ≥$75,000 | 19.2% | 15.1% | 11.5% | ||

| Beta blocker use | 32.3% | 37.8% | 34.5% | 0.354 | |

| Smoking | Current smoker | 8.2% | 11.7% | 7.7% | 0.131 |

| Inhaled steroid use | 2.2% | 2.7% | 3.2% | 0.793 | |

| Oral steroid use | 0.9% | 0.7% | 1.4% | 0.622 | |

| Hormone replacement therapy since last visit (Female only) |

9.9% | 5.1% | 7.6% | 0.067 | |

NOTE: BMI categories are defined as follows: normal (<25 kg/m2), grade 1 overweight (25-30 kg/m2), grade 2 overweight (30-40 kg/m2), and grade 3 overweight (>40 kg/ m2).

denotes p<0.05

denotes p<0.0001

CES-D denotes Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale

Association of awakening cortisol, CAR, early decline, late decline and AUC with BMI and WC

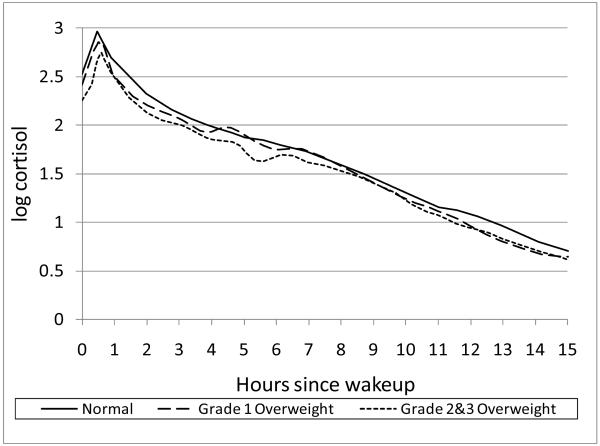

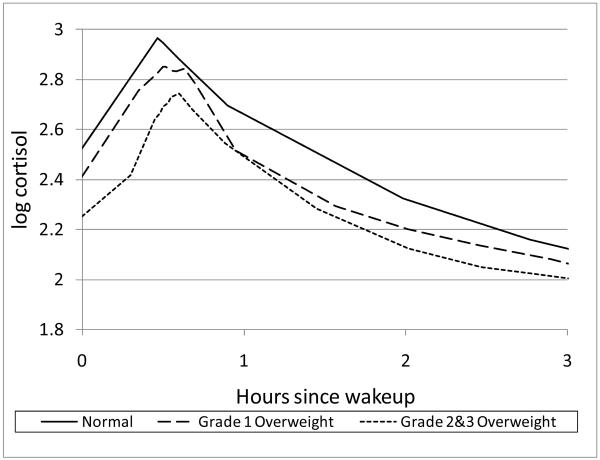

Figure 2 depicts the variation in diurnal cortisol curve from awakening to bedtime based on BMI category with notably lower cortisol values seen in those with higher BMI. This is more visibly apparent in the awakening hours as depicted in Figure 3. Table 2 demonstrates the individual cortisol variables relative to WC and BMI modeled as continuous variables and adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and diabetes status. Both WC and BMI showed a significant negative association with awakening cortisol, AUC awakening rising, and AUC early decline. No statistically significant differences were noted in the awakening rise or late decline; however, the early decline portion of the salivary curve was flattened with a significantly positive association in the slope for both BMI and WC. Following additional adjustments for socioeconomic status, beta blockers, steroid use, HRT use, and current smoking status, these associations persisted, although some associations with total AUC were attenuated. Findings were similar when BMI was modeled as a categorical variable, although BMI category was not significantly associated with the early decline and total AUC (data not shown). Because a prior study suggested a non-linear association between the diurnal cortisol slope and BMI (29), we performed subsidiary analyses in which a quadratic term was included for BMI and WC. The results of these analyses were similar to those from the linear model, suggesting that there was not a non-linear association between cortisol and BMI and WC in our population.

Figure 2.

Diurnal Curve for entire sample set

Figure 3.

Diurnal Curve during awakening hours

TABLE 2.

Mean differences in BMI and log WC for each one log-unit change in Cortisol parameters for entire cohort by age, race/ethnicity, gender, and diabetes status

| BMI1 | Waist circumference1 | BMI2 | Waist circumference2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta coefficient (95% CI) | Beta coefficient (95% CI) | Beta coefficient (95% CI) | Beta coefficient 95% CI) | |

| Awakening (time zero) | −0.0152* (−0.0217, −0.0087) |

−0.0046* (−0.0071, −0.0021) |

−0.0141* (−0.0205, −0.0076) |

−0.0042* (−0.0067, −0.0018) |

| Awakening rise (awakening – 0 hr to peak – 30 minutes) (slope) |

0.0008 (−0.0113, 0.0129) |

−0.0003 (−0.0049, 0.0043) |

−0.0008 (−0.0131, 0.0116) |

−0.0009 (−0.0055, 0.0038) |

| Early decline (peak – 30 minutes to 2 hours) (slope) | 0.0063* (0.0012, 0.0114) |

0.0022* (0.0001, 0.0042) |

0.0064* (0.0012, 0.0115) |

0.0023* (0.0002, 0.0043) |

| Late decline (2 hours to bedtime – 16hour) (slope) | 0.0001 (−0.0006, 0.0008) |

0.0000 (−0.0003, 0.0002) |

0.0001 (−0.0006, 0.0008) |

0.0000 (−0.0003, 0.0002) |

| AUC full range (Waking 0 hr to bedtime – 16 hr) (area) | −0.0857* (−0.1696, −0.0018) |

−0.0284 (−0.0596, 0.0028) |

−0.0782 (−0.1624, 0.006) |

−0.0253 (−0.0565, 0.006) |

| AUC awakening rising (awakening 0 hr to peak – 30 min) (area) |

−0.0075* (−0.0106, −0.0044) |

−0.0023* (−0.0035, −0.0012) |

−0.0071* (−0.0102, −0.0041) |

−0.0022* (−0.0034, −0.0011) |

| AUC early decline (peak – 30 min to 2 hr) (area) | −0.0151* (−0.0233, −0.0069) |

−0.0047* (−0.0076, −0.0017) |

−0.0145* (−0.0227, −0.0064) |

−0.0044* (−0.0074, −0.0015) |

| AUC late decline (2hr to bedtime – 16 hr) (area) | −0.0631 (−0.1399, 0.0136) |

−0.0214 (−0.05, 0.0072) |

−0.0565 (−0.1336, 0.0206) |

−0.0186 (−0.0474, 0.0101) |

denotes p<0.05

NOTE: Beta coefficients reflect relative increase in slope or AUC per unit increase in BMI or WC.

denotes adjusted values for age, race/ethnicity, sex, and diabetes status

denotes additional adjustments for socioeconomic status, beta blockers, steroids, HRT, and current smoking

Because cortisol profiles may vary by sex (34), we determined whether there was effect modification by sex on the association between cortisol curve parameters and BMI and WC. In stratified analyses, the results suggested that the association between awakening cortisol and AUC parameters and BMI was slightly stronger in men than women (awakening cortisol: β=−0.021, 95% CI: −0.031 to −0.011 in men and β=−0.011, 95% CI: −0.019 to −0.002 in women; total AUC: β=−0.16, 95% CI: −0.28 to −0.035 in men and β=−0.044, 95% CI: −0.16 to 0.067 in women). Sex stratified associations were similar for WC (data not shown). There was not, however, evidence of statistical interaction and the direction of association was similar in men and women (p-value=0.094 and 0.079 for sex interaction of cortisol curve measures with BMI and WC, respectively). Measures of cortisol slope (awakening rise, early decline and late decline) were not associated with BMI or waist circumference in either sex (data not shown).

Secondary analysis with exclusion of impaired fasting glucose and diabetes subjects

Table 3 summarizes the association between WC and BMI and cortisol variables among individuals with normal fasting glucose, as the association of diabetes with waist circumference and BMI and HPA measures might confound the observed association. Following multivariable adjustment, higher BMI and waist circumference showed a significant inverse association with awakening cortisol, total AUC, AUC awakening rise, AUC early decline, and AUC late decline. BMI and waist circumference were not associated with awakening rise, early decline, or late decline.

TABLE 3.

Mean differences in BMI and log WC for each one log-unit change in Cortisol parameters for individuals with normal fasting glucose, adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, gender, and diabetes status, socioeconomic status, beta blockers, steroids, HRT, and current smoking

| BMI | Waist circumference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta coefficient | 95% CI | Beta coefficient | 95% CI | |

| Awakening (time zero) | −0.0205* | (−0.029, −0.012) | −0.0065* | (−0.0099, −0.0032) |

| Awakening rise (awakening – 0 hr to peak – 30 minutes) (slope) | 0.0016 | (−0.016, 0.019) | −0.0001 | (−0.0065, 0.0062) |

| Early decline (peak – 30 minutes to 2 hours) (slope) | 0.0063 | (−0.001, 0.013) | 0.0026 | (−0.0002, 0.0054) |

| Late decline (2 hours to bedtime – 16hour) (slope) | −0.0002 | (−0.001, 0.001) | −0.0001 | (−0.0005, 0.0002) |

| AUC full range (Waking 0 hr to bedtime – 16 hr) (area) | −0.1963* | (−0.297, −0.096) | −0.0627* | (−0.1007, −0.0247) |

| AUC awakening rising (awakening 0 hr to peak – 30 min) (area) | −0.0101* | (−0.014, −0.006) | −0.0033* | (−0.0049, −0.0017) |

| AUC early decline (peak – 30 min to 2 hr) (area) | −0.0225* | (−0.033, −0.012) | −0.0070* | (−0.011, −0.0031) |

| AUC late decline (2hr to bedtime – 16 hr) (area) | −0.1638* | (−0.256, −0.072) | −0.0524* | (−0.0869, −0.0179) |

denotes p<0.05

NOTE: Beta coefficients reflect relative increase in slope or AUC per unit increase in BMI or WC.

DISCUSSION

In this study we found a cross-sectional association of the diurnal cortisol profile with markers of overall and abdominal obesity. These findings were independent of demographics, socioeconomic status, medications, and smoking. We noted a significant negative association of BMI and WC with awakening cortisol and early decline, as well as the respective AUCs.

Studies to date analyzing cortisol levels in relation to obesity markers have yielded mixed results. Our findings of an inverse association of BMI and WC with morning cortisol levels are consistent with those of three other studies (8, 20, 35), all of which were fairly large population-based samples, although they were more limited in age range and/or race/ethnicity. A few studies have noted a positive correlation between urinary cortisols and WHR (2, 11), subcutaneous adipose tissue (12), and BMI (13). As suggested by Walker et al, this paradox may be due to enhanced peripheral metabolic clearance of cortisol in obesity or altered central HPA control (8). Bjorntorp et al have also noted that urinary collections have their own inherent weaknesses including lack of information on the kinetics of HPA axis regulation (20).

The physiology of cortisol metabolism may explain these findings. 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 (11β-HSD1) is an enzyme that converts hormonally active glucocorticoids like cortisol into inactive metabolites like cortisone; its expression is thought to cause higher intradipose tissue cortisol levels in obese subjects, perhaps through its reverse reductase action (1). Rask et al found that higher BMI was associated with higher 11β-HSD1 by adipose tissue biopsy, which would be difficult to detect in serum and salivary samples (13). They also suggest that perhaps the reductase activity is impaired at the level of the liver, yielding lower serum levels. This may imply that in obesity there may be tissue specific alterations in cortisol metabolism (13). Travison et al found among 999 subjects followed over 2 separate visits that there was a negative correlation between changes in serum cortisol levels collected within 4 hours of waking and increases in BMI over time (9). They also suggest that perhaps overexpression of 11β-HSD1 in adipose tissue may cause local regeneration of cortisol, but with minimal effect on circulating levels.

Long-term activation of HPA axis is associated with decreased diurnal variability of cortisol (36). It has been noted in men with “burned-out” diurnal cortisol secretion (including lower awakening cortisol and flatter slope) that there is a negative correlation with waist-to-hip ratio (37). Total cortisol secretion was lower in this group with a flatter diurnal cortisol curve compared to men with a more normal high variability diurnal curve (37). Thus, low daily cortisol variability may reflect a prior over-stimulated HPA axis and previously high cortisol levels may have stimulated visceral fat accumulation (3). Because our study was cross-sectional, we cannot confirm a temporal sequence.

Our study has several strengths. First, this is one of the largest population-based studies to date reporting the association of awakening and diurnal salivary cortisol with markers of overall and central obesity. Second, salivary cortisol sample collection included the use of track caps for recording sample times to increase compliance in sample collection. Third, salivary cortisol sample collection occurred over 3 days, which has not been done in prior studies, allowing a more accurate determination of each participant’s diurnal cortisol pattern. Finally, we were able to adjust for smoking, many medications, and other potentially confounding variables using data collected in MESA.

Several limitations should be kept in mind, however, in interpreting our data. First, this is a cross-sectional study so we are unable to determine whether hormonal dysfunction preceded or occurred after developing higher levels of obesity. Second, many medications can theoretically affect salivary cortisol (33), and our study only had data on a subset of these. Third, we did not have data to more objectively assess visceral fat content via abdominal imaging. Associations of metabolic risk factors have been noted to be less pronounced in peripheral obesity rather than central obesity (37); however, we found similar patterns of association using our estimate of overall obesity (BMI) and our estimate of central adiposity (WC). Fourth, we did not have data on specific subgroups of obese individuals who have been shown to have flattened diurnal cortisol profiles, including those with atypical depression(38) and sleep apnea(39); therefore, we could examine these factors as potential mediators and/or effect modifiers of our observed associations. Fifth, while we found significant associations between cortisol curve parameters and BMI and WC, they were small and their clinical significance uncertain; however, our associations are of similar magnitude to that observed in other studies. For example, the unadjusted correlation coefficient between waking cortisol and BMI and WC were −0.15 (p<0.0001) and −0.11 (p<0.0001), respectively, in our population. Other studies have found correlations of −0.09 to −0.26 between morning cortisol and BMI (12, 14, 24, 28). And finally, this study lacked data concerning sex steroid and growth hormone levels, which may have been potential confounders in the association as they may affect cortisol and body fat levels (20).

Our population-based study comprehensively examined components of the diurnal cortisol curve in relation to obesity markers. The long-term effects of dysregulation of the neuroendocrine stress system (i.e. allostatic load) is thought to be one potential mechanism through which individuals are predisposed to metabolic disorders (40). Longitudinal studies to assess neuroendocrine tone over time as adiposity develops are necessary to further delineate the role of the HPA axis in development of obesity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by contracts N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. MESA was supported by contracts NO1-HC-95159 through NO1-HC-95165 and NO1-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org. MESA Stress Study was supported by RO1 HL101161-01A1 (PI: Dr. Diez-Roux). Dr. Golden was supported by a Patient-Oriented Mentored Scientist Award through the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD (5 K23 DK071565). Dr. Champaneri was supported by a training grant (T32 Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award). We thank Dr. Gary Wand for his thoughtful review of our analyses and manuscript.

Grants/fellowships: MESA was supported by contracts NO1-HC-95159 through NO1-HC-95165 and NO1-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. MESA Stress Study was supported by RO1 HL10161-01A1 (PI: Dr. Diez-Roux). Dr. Golden was supported by a Patient-Oriented Mentored Scientist Award through the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD (5 K23 DK071565). Dr. Champaneri was supported by a training grant (T32 Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award).

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: SC, XX, MC, AB, TS, AD, and SS have nothing to declare. ADR is funded by a research grant from NIH. SHG is funded by NIH and NHLBI contracts which support MESA and MESA stress.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anagnostis P, Athyros VG, Tziomalos K, Karagiannis A, Mikhailidis DP. Clinical review: The pathogenetic role of cortisol in the metabolic syndrome: a hypothesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(8):2692–701. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasquali R, Cantobelli S, Casimirri F, et al. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in obese women with different patterns of body fat distribution [see comments] J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77(2):341–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.2.8393881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weaver JU, Kopelman PG, McLoughlin L, Forsling ML, Grossman A. Hyperactivity of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in obesity: a study of ACTH, AVP, beta-lipotrophin and cortisol responses to insulin-induced hypoglycaemia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1993;39(3):345–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1993.tb02375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasquali R, Ambrosi B, Armanini D, et al. Cortisol and ACTH response to oral dexamethasone in obesity and effects of sex, body fat distribution, and dexamethasone concentrations: a dose-response study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(1):166–75. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.1.8158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallerius S, Rosmond R, Ljung T, Holm G, Bjorntorp P. Rise in morning saliva cortisol is associated with abdominal obesity in men: a preliminary report. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26(7):616–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03347017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epel ES, McEwen B, Seeman T, et al. Stress and body shape: stress-induced cortisol secretion is consistently greater among women with central fat. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):623–32. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duclos M, Marquez PP, Barat P, Gatta B, Roger P. Increased cortisol bioavailability, abdominal obesity, and the metabolic syndrome in obese women. Obes Res. 2005;13(7):1157–66. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker BR, Soderberg S, Lindahl B, Olsson T. Independent effects of obesity and cortisol in predicting cardiovascular risk factors in men and women. J Intern Med. 2000;247(2):198–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travison TG, O’Donnell AB, Araujo AB, Matsumoto AM, McKinlay JB. Cortisol levels and measures of body composition in middle-aged and older men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;67(1):71–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward AM, Fall CH, Stein CE, et al. Cortisol and the metabolic syndrome in South Asians. Clin Endocrinol. 2003;58(4):500–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marin P, Darin N, Amemiya T, Andersson B, Jern S, Bjorntorp P. Cortisol secretion in relation to body fat distribution in obese premenopausal women. Metabolism. 1992;41(8):882–6. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(92)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Misra M, Bredella MA, Tsai P, Mendes N, Miller KK, Klibanski A. Lower growth hormone and higher cortisol are associated with greater visceral adiposity, intramyocellular lipids, and insulin resistance in overweight girls. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295(2):E385–E392. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00052.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rask E, Olsson T, Soderberg S, et al. Tissue-specific dysregulation of cortisol metabolism in human obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(3):1418–21. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marniemi J, Kronholm E, Aunola S, et al. Visceral fat and psychosocial stress in identical twins discordant for obesity. J Intern Med. 2002;251(1):35–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunner EJ, Hemingway H, Walker BR, et al. Adrenocortical, autonomic, and inflammatory causes of the metabolic syndrome: nested case-control study. Circulation. 2002;106(21):2659–65. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038364.26310.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purnell JQ, Kahn SE, Samuels MH, Brandon D, Loriaux DL, Brunzell JD. Enhanced cortisol production rates, free cortisol, and 11beta-HSD-1 expression correlate with visceral fat and insulin resistance in men: effect of weight loss. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296(2):E351–E357. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90769.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zamboni M, Armellini F, Turcato E, et al. Relationship between visceral fat, steroid hormones and insulin sensitivity in premenopausal obese women. J Intern Med. 1994;236(5):521–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1994.tb00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hautanen A, Raikkonen K, Adlercreutz H. Associations between pituitary-adrenocortical function and abdominal obesity, hyperinsulinaemia and dyslipidaemia in normotensive males. J Intern Med. 1997;241(6):451–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1997.tb00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosmond R, Dallman MF, Bjorntorp P. Stress-related cortisol secretion in men: relationships with abdominal obesity and endocrine, metabolic and hemodynamic abnormalities. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(6):1853–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.6.4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjorntorp P, Holm G, Rosmond R. Hypothalamic arousal, insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes mellitus [see comments] Diabet Med. 1999;16(5):373–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Power C, Li L, Hertzman C. Associations of early growth and adult adiposity with patterns of salivary cortisol in adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(11):4264–70. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Therrien F, Drapeau V, Lalonde J, et al. Awakening cortisol response in lean, obese, and reduced obese individuals: effect of gender and fat distribution. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(2):377–85. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyle SH, Surwit RS, Georgiades A, et al. Depressive symptoms, race, and glucose concentrations: the role of cortisol as mediator. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(10):2484–8. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumari M, Chandola T, Brunner E, Kivimaki M. A nonlinear relationship of generalized and central obesity with diurnal cortisol secretion in the Whitehall II study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(9):4415–23. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, et al. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(9):871–81. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranjit N, Diez-Roux AV, Sanchez B, et al. Association of salivary cortisol circadian pattern with cynical hostility: multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(7):748–55. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181ad23e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derr RL, Cameron SJ, Golden SH. Pre-analytic considerations for the proper assessment of hormones of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis in epidemiological research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21(3):217–26. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-0011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization . Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry: report of a WHO Expert Committee. Vol. 854. World Health Organization; 1995. pp. 1–452. World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hajat A, Diez-Roux A, Franklin TG, et al. Socioeconomic and race/ethnic differences in daily salivary cortisol profiles: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(6):932–43. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Badrick E, Kirschbaum C, Kumari M. The relationship between smoking status and cortisol secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(3):819–24. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Supplement 1):S62–S69. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Champaneri S, Xu X, Carnethon MR, Bertoni AG, Seeman T, Diez Roux A, Golden SH. Diurnal Salivary Cortisol and Urinary Catecholamines Are Associated with Diabetes Mellitus: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Metabolism. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.11.006. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Granger DA, Hibel LC, Fortunato CK, Kapelewski CH. Medication effects on salivary cortisol: tactics and strategy to minimize impact in behavioral and developmental science. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(10):1437–48. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uhart M, Chong RY, Oswald L, Lin PI, Wand GS. Gender differences in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(5):642–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varma VK, Rushing JT, Ettinger WH., Jr High density lipoprotein cholesterol is associated with serum cortisol in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(12):1345–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kyrou I, Chrousos GP, Tsigos C. Stress, visceral obesity, and metabolic complications. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1083:77–110. doi: 10.1196/annals.1367.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bjorntorp P. Visceral obesity: a “civilization syndrome”. Obes Res. 1993;1(3):206–22. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1993.tb00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gold PW, Chrousos GP. Organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in melancholic and atypical depression: high vs low CRH/NE states. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7(3):254–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vgontzas AN, Pejovic S, Zoumakis E, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in obese men with and without sleep apnea: effects of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(11):4199–207. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(3):171–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]