Abstract

Objective:

Previous research has shown that perceived social norms are among the strongest predictors of drinking among young adults. Research has also consistently found religiousness to be protective against risk and negative health behaviors. The present research evaluates the extent to which reliance on God, prayer, and religion moderates the association between perceived social norms and drinking.

Method:

Participants (n = 1,124 undergraduate students) completed a cross-sectional survey online, which included measures of perceived norms, religious values, and drinking. Perceived norms were assessed by asking participants their perceptions of typical student drinking. Drinking outcomes included drinks per week, drinking frequency, and typical quantity consumed.

Results:

Regression analyses indicated that religiousness and perceived norms had significant unique associations in opposite directions for all three drinking outcomes. Significant interactions were evident between religiousness and perceived norms in predicting drinks per week, frequency, and typical quantity. In each case, the interactions indicated weaker associations between norms and drinking among those who assigned greater importance to religiousness.

Conclusions:

The extent of the relationship between perceived social norms and drinking was buffered by the degree to which students identified with religiousness. A growing body of literature has shown interventions including personalized feedback regarding social norms to be an effective strategy in reducing drinking among college students. The present research suggests that incorporating religious or spiritual values into student interventions may be a promising direction to pursue.

Social influences are among the most significant predictors of problematic drinking among young adults (Baer, 2002). Among young adults, perceptions of peers' drinking, which often differ from peers' actual drinking, are associated with one's own alcohol use (Borsari and Carey, 2003). Alternatively, religious involvement and commitment have been consistently associated with reduced alcohol consumption (Koenig et al., 2012). The present research was designed to consider whether religious involvement and commitment might moderate peer influences on drinking.

College drinking

The literature on drinking among undergraduates indicates that consuming alcohol in college is common, with a lifetime annual prevalence of 81% among college students (Johnston et al., 2012). Recent findings from the Monitoring the Future study indicate that approximately 36% of college students (43% of men and 32% of women) report having consumed five or more drinks on an occasion at least once in the previous 2 weeks (Johnston et al., 2012). Moreover, research has found that college men have a higher rate of heavy episodic drinking (43%) compared with their female counterparts (32%; Johnston et al., 2012). The behaviors and consequences associated with heavy alcohol use are extensive and range in severity. Alcohol-related problems include criminal behavior, problems related to academics, severe injury, illness, unwanted sexual experiences, sexually transmitted infection, and death (Hingson et al., 2005).

Social norms and alcohol

Social norms have been consistently shown to be a strong predictor of alcohol consumption among college students (Borsari and Carey, 2001, 2003). In fact, social norms have been found to be a stronger predictor of alcohol consumption in college students than other known influences including gender, fraternity or sorority membership, drinking motives, alcohol expectancies, and evaluation of alcohol effects (Neighbors et al., 2007). Descriptive social norms refer to an individual's perception of how others are actually behaving, for example a student's perception of how much the average college student drinks (Neighbors et al., 2004). Specifically, research looking at descriptive college drinking norms has shown that perceptions of other students' drinking are correlated with one's own drinking, although both men and women overestimate the quantity and frequency of drinking of their same-sex peers (Lewis and Neighbors, 2004; Suls and Green, 2003). Further, students who overestimate the amount their peers drink and who perceive their friends and parents as more approving of drinking have more alcohol-related problems because they drink more (Borsari and Carey, 2003; Prentice and Miller, 1993).

Religiousness and alcohol

The association between religiousness and alcohol consumption has been well documented. Alcoholics Anonymous, which is based largely on spiritual principles, has been found to be at least as effective as other approaches (Koenig et al., 2012). Five of the 12 steps of Alcoholics Anonymous include direct references to God or a higher power. The final step assumes the occurrence of a “spiritual awakening” and encourages the practice and sharing of spiritual principles with others.

Outside of the context of treatment and recovery, a relatively large number of studies have examined associations between religion and alcohol consumption. In a review of 278 quantitative studies examining associations between religiousness and alcohol consumption, 240 (86%) reported a negative association between religiousness and alcohol use (Koenig et al., 2012). The same proportion of prospective studies (42 of 49: 86%) found higher religiousness to be associated with less subsequent alcohol use. A growing body of evidence continues to demonstrate the robust negative association between religion and alcohol consumption among adolescents and college students, particularly for those who identify themselves as being intrinsically religious (e.g., Allport and Ross, 1967; Bahr et al., 1998; Brody et al., 1996; Brown et al., 2008; Button et al., 2010; Galen and Rogers, 2004; Johnson et al., 2008; Luczak et al., 2003; Menagi et al., 2008; Patock-Peckham et al., 1998; Wills et al., 2003). Among adolescents, the effect of religiousness as a protective factor for alcohol and substance use has been shown across gender, age, and socioeconomic status and is not limited to a particular subgroup (Wills et al., 2003). The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health found that public (i.e., religious attendance and affiliation) and private (i.e., private prayer and personal importance of religion) religiousness served as a protective mechanism against substance use (Nonnemaker et al., 2003). Recent research conducted by Brown et al. (2008) found that intrinsic religiousness, defined as motivation for engaging in religious behavior arising out of one's faith (e.g., the practice of loving one's neighbor as oneself) versus utilitarian motives (e.g., going to church to see friends), was associated with less frequent alcohol use, lower quantities of alcohol consumption, and fewer alcohol-related problems. Further, internalization of religious identity, as operationalized by religious commitment and religious coping, has been associated with less drinking among college students (Menagi et al., 2008).

A growing body of literature suggests that at least part of the attenuating effect of religiousness on alcohol consumption appears to be the result of having greater peer influences who are religious (Button et al., 2010; Chawla et al., 2007; Galen and Rogers, 2004; Johnson et al., 2008). Social Identity Theory (Abrams and Hogg, 1999; Terry and Hogg, 1996) suggests that an individual's behavior is governed more greatly by the groups the individual identifies with or refers to in seeking appropriate normative behavior. Consistent with this perspective, recent findings have shown social identity to moderate the influence of perceived norms on drinking (Neighbors et al., 2010; Reed et al., 2007).

Applying this perspective to the relationship between religiousness and drinking, we might expect that the type of support one develops from the influence of religion and religious peers may override or buffer the social influences found across university campuses where heavy drinking episodes are prevalent. The negative association between religiousness and alcohol problems has been attributed to proscriptions in the social network (Button et al., 2010). For example, Johnson et al. (2008) found that religious and spiritual involvement was negatively related to alcohol consumption by means of social influences and negative beliefs toward alcohol. Furthermore, Galen and Rogers (2004) found that religious participants (particularly those in denominations where abstinence is valued) indicated greater endorsement of negative attitudes about alcohol and were less motivated to drink. These authors reported that two key aspects of religiousness's role with regard to alcohol consumption were those of social behavioral proscriptions and indirect discouragement from religious influences and peers.

Present study

The present study builds on this robust literature by examining whether religious values moderate the relationship between social norms and drinking behaviors. Moreover, theory and previous findings suggest that peer influences may differ in quality and magnitude for those who are more religiously involved and committed. Thus, the present analyses were designed to directly evaluate religiousness as a moderator of the association between perceived norms and drinking in a large sample of college students. We expected that the association between perceived norms and drinking would be weaker among students who endorsed stronger religious values.

Method

Participants and procedures

Participants were 1,124 undergraduate students (55.1% female, 44.9% male) recruited from a large northwestern university. A total of 2,113 students were invited to participate 4 days after their 21st birthday. Just more than half of them (n = 1,124; 53%) responded to the invitation and participated in the study. All participants provided informed consent and completed the survey online. Additional details regarding the sample and recruitment are available elsewhere (Neighbors et al., 2011). All participants in the present study were 21 years old. Race representation was 61.8% White, 25.9% Asian, 6.2% multiracial, and 6.1% other. Ethnic representation was 95.9% non-Hispanic and 4.1% Hispanic.

During three academic quarters in 2008, all registered undergraduate students who turned 21 and had their contact information provided by the registrar's office were invited to participate in a confidential online survey about 21st birthday celebrations. Participants were asked to answer questions regarding alcohol use during the previous 3 months and other alcohol-related psychosocial measures. The current research was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board. In accordance with human subjects' protections, participants were instructed that they did not have to answer any items they did not wish to answer. This resulted in a small proportion of missing data, ranging from 8 (0.71%) to 20 (1.77%) missing responses depending on the variable. Participants were compensated $30 for participation in this study.

Measures

Religious values.

Religious values were assessed using Jessor's Value on Religion Scale (Jessor and Jessor, 1977), comprised of four items on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 = not at all important to 3 = very important (Wills et al., 2003). Participants were asked to rate how important it is “to believe in God,” “to be able to rely on religious teaching when you have a problem,” “to be able to turn to prayer when facing a personal problem,” and “to rely on your religious beliefs as a guide for day-to-day living.” The score for religious values was computed by taking the mean of the four items. The reliability coefficient (Cronbach's α) for these four items was .96. This measure was chosen versus a large number of measures available of religiousness and is conceptually similar to Allport and Ross's (1967) construct of intrinsic religiousness. We selected this measure based on its brevity, previous association with substance use, and previous demonstration as a moderator of other factors associated with substance use (Wills et al., 2003).

Perceived norms.

The Drinking Norms Rating Form (Baer et al., 1991) was used to evaluate perceived descriptive norms. Perceived norms were assessed by asking participants about their perceptions of typical student alcohol consumption. Students were asked to estimate the amount of alcohol consumed by a typical student each day of the week. The instructions were presented as follows: “Consider a typical week during the three months. How much alcohol, on average (measured in number of drinks), does a typical [University Name] student drink on each day of a typical week?” Participants entered their responses on a calendar grid that provided seven blanks, one for each day of the week. The scores reflect the sum of the seven responses and thus indicate the perceived number of drinks consumed per week by the typical student. This measure has been shown to significantly correlate with measures of drinking (Baer et al., 1991; Borsari and Carey, 2000; Neighbors et al., 2004).

Drinking outcomes.

Drinks per week, drinking frequency, and typical quantity consumed were evaluated as drinking outcomes. The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins et al., 1985) was used to measure number of drinks per week. Participants filled in the average number of standard drinks consumed and the time period of consumption for every day of the week over the past 3 months. The instructions were presented as follows: “Consider a typical week during the past three months. How much alcohol, on average (measured in number of drinks), did you drink on each day of a typical week?” Participants entered seven responses in a calendar grid format, one for each day of the week. The scores reflect the sum of the seven responses and thus indicate the average number of drinks consumed per week during the past 3 months.

The Quantity/Frequency/Peak Alcohol Use Index (Dimeff et al., 1999) was also used to identify typical drinking patterns over the past month. This measure includes a single item assessing frequency of drinking over the previous month. Participants responded on a 12-point scale (0 = I do not drink at all; 1 = about once per month; 2 = once per month; 3 = two times per month; 4 = three times per month; 5 = once a week; 6 = twice a week; 7 = three times a week; 8 =four times a week; 9 =five times a week; 10 = six times a week; 11= every day). This measure also includes a single item assessing average quantity of alcohol consumed on a typical occasion in the previous month. Participants responded with how much alcohol they typically drank on a given weekend evening during the past month, from 0 to 25 or more drinks.

Results

Analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, skewness values, and zero-order correlations among all major study variables. All variables exhibited some degree of positive skew (i.e., importance of religion = 0.46; perceived norms = 2.10; drinks per week = 2.98; drinking frequency = 0.19; typical quantity = 1.56). Only one of the outcomes, drinks per week, exhibited skew large enough to be considered extreme (Kline, 2011). For this outcome, we performed a log+1 transformation, which reduced the skewness value to 0.30. Analyses of drinks per week were conducted using the transformed and untransformed variable and produced identical conclusions. Results are therefore presented using the untransformed variable.

Table 1.

Zero-order correlations among variables

| Measure | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. |

| 1. Importance of religion | – | ||||

| 2. Perceived norms | .08** | – | |||

| 3. Drinks per week | -.17*** | .31*** | – | ||

| 4. Drinking frequency | -.25*** | .11*** | .66*** | – | |

| 5. Typical quantity | -.18*** | .24*** | .70*** | .60*** | – |

| M | 1.17 | 16.44 | 6.52 | 3.39 | 2.87 |

| SD | 1.13 | 10.80 | 10.06 | 2.60 | 2.64 |

| Skewness | 0.46 | 2.10 | 2.98 | 0.19 | 1.56 |

Note: ns ranged from 1,096 to 1,116 depending on missing responses.

p < .01;

p < .001.

Overall, religious values were negatively associated with all three drinking outcomes (i.e., drinks per week, frequency of drinking, and typical quantity consumed). Using Cohen's (1992) criteria, the magnitudes of these associations were in the small (r = .10) to medium (r = .30) range. There was a small positive association between religious values and perceived drinking norms. Perceived norms were positively associated with all three drinking outcomes, with correlations in the small to medium range.

Multiple regression analyses were used to assess the possibility of a buffering effect of importance of religious values in the association between perceived norms and drinks per week, frequency of drinking, and typical quantity consumed. Perceived norms, importance of religious values, and the two-way interaction term were included as predictors. Predictors were mean centered (Aiken and West, 1991). Table 2 presents the results of this regression analysis for each of the respective outcome variables.

Table 2.

Regression results for drinking as a function of religion and perceived norms

| Criterion | Predictor | B | SE(B) | β | t |

| Drinks per week | Religion | -1.72 | 0.25 | -.19 | -6.90*** |

| Perceived norms | 0.31 | 0.03 | .33 | 11.87*** | |

| Religion × Perceived Norms | -0.13 | 0.02 | -.15 | -5.27*** | |

| Drinking frequency | Religion | -0.62 | 0.07 | -.27 | -9.30*** |

| Perceived norms | 0.04 | 0.01 | .15 | 5.06*** | |

| Religion × Perceived Norms | -0.02 | 0.01 | -.09 | -3.23** | |

| Typical quantity | Religion | -0.48 | 0.07 | -.20 | -7.04*** |

| Perceived norms | 0.06 | 0.01 | .26 | 8.92*** | |

| Religion × Perceived Norms | -0.02 | 0.01 | -.07 | -2.39* |

p < .05;

p< .01;

p< .001.

Results indicated that religious values and perceived norms were significantly and uniquely associated with all three drinking outcomes, in opposite directions. Specifically, as hypothesized, endorsing religious values predicted lower drinking outcomes, and greater perception of other students' drinking predicted higher drinking outcomes.

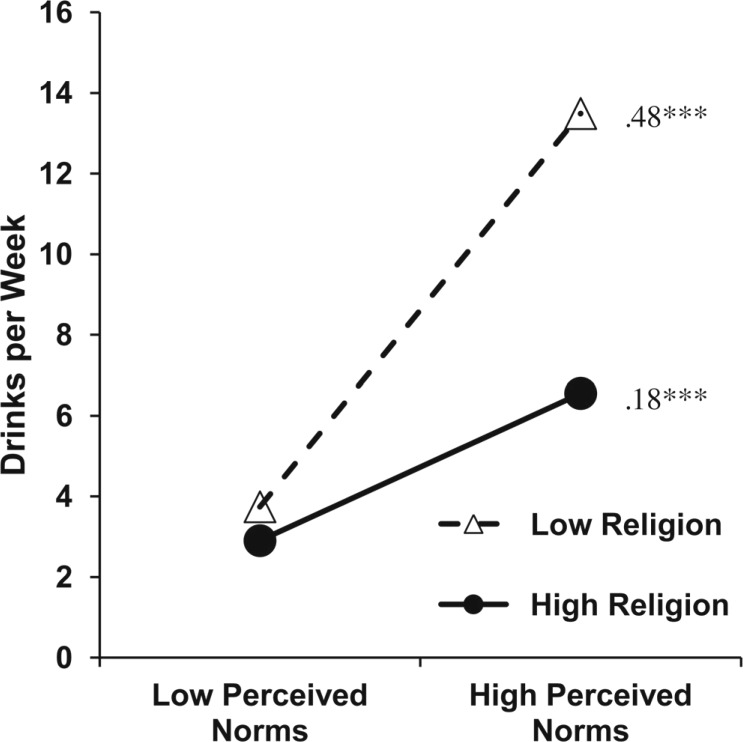

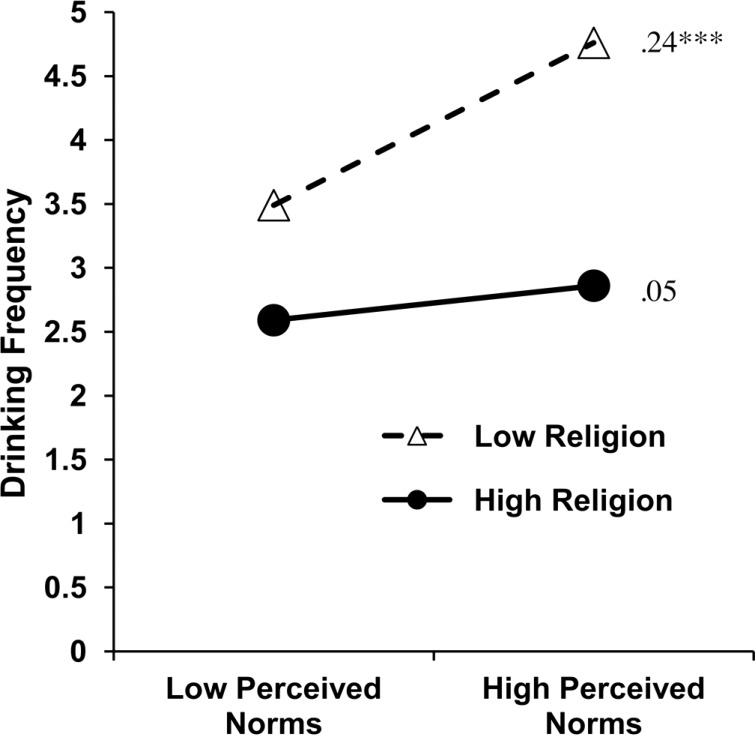

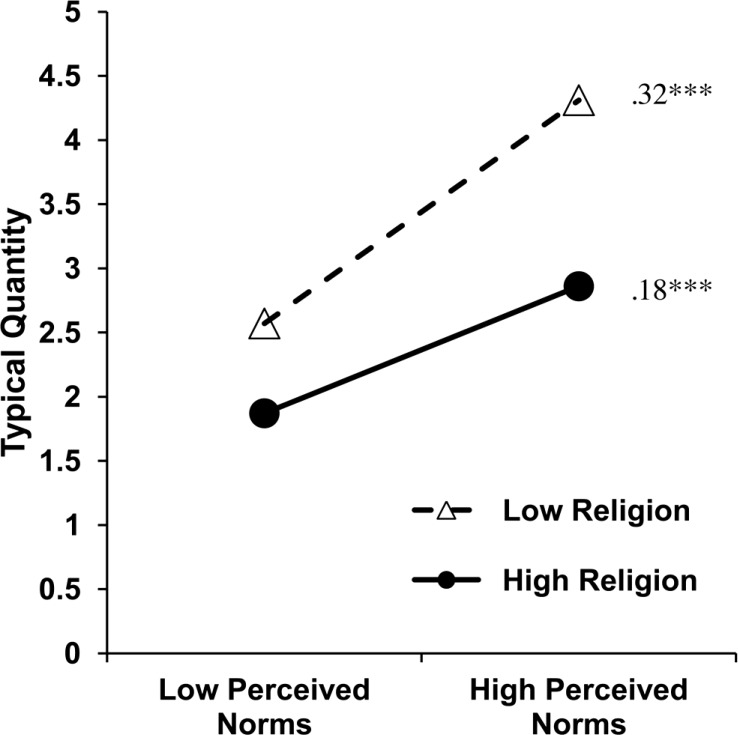

As expected, although those with greater perceived norms generally reported more drinking, this effect was moderated by religious values. Significant interactions were evident between religious values and perceived norms in predicting drinks per week, typical frequency, and typical quantity. Figures 1–3 present the predicted cell means, derived from the regression equation, with higher and lower values displayed as one standard deviation above and below the respective centered means (Aiken and West, 1991; Cohen et al., 2003). Specifically, the association between perceived norms and drinking outcomes was weaker for those who assigned greater importance to religious values.

Figure 1.

Drinks per week as a function of perceived norms and religious values

***p < .001.

Figure 3.

Frequency of drinking as a function of perceived norms and religious values

***p<.001.

Figure 2.

Typical quantity of alcohol consumed as a function of perceived norms and religious values

***p<.001.

Tests of simple slopes were performed on each of the three drinking outcomes. The parameter estimates and associated probability values can also be seen in the figures. Analyses revealed that although perceived norms were significantly and positively associated with drinks per week for those with lower (-1 SD) religious values (β = .48, p < .001), the relationship was significantly weaker for those with higher (+1 SD) religious values (β = .18, p < .001.) A similar pattern emerged for typical quantity consumed such that although perceived norms were significantly and positively associated with drinking for those with lower (-1 SD) religious values (β = .32, p < .001), this relationship was significantly weaker for those with higher (+1 SD) religious values (β = .18, p <.001). Finally, simple slopes analyses revealed that whereas perceived norms were significantly and positively associated with drinking frequency for those with lower (-1 SD) religious values (β = .24, p < .001), perceived norms were not significantly associated with drinking frequency for those with higher (+1 SD) religious values (β = .05, n.s.). Conclusions were unchanged when gender and ethnicity were entered as covariates in the analyses.

Additional analyses were conducted to evaluate whether specific aspects of religiousness were responsible for the reduced influence of perceived norms on drinking. Thus, we examined each item of the religiousness composite separately to determine whether believing in God, relying on religious teachings, praying in response to personal problems, or relying on religious beliefs as a guide for daily living moderated associations between perceived norms and drinking. Results revealed significant interactions between each aspect of religiousness and perceived norms for all three drinking outcomes, which mirrored the composite religiousness results presented in Figures 1–3. All interactions were significant except for the interaction between relying on religious beliefs as a guide for daily living and perceived norms in predicting typical quantity, where p = .054.

Discussion

The present study hypothesized that religious values would buffer the relationship between perceived norms and drinking. Our findings indicate, consistent with the hypothesis, that the relationship between alcohol consumption and perceived norms is moderated by religious involvement and commitment. As with previous studies (e.g., Brown et al., 2008; Galen and Rogers, 2004; Wills et al., 2003), we found religiousness to be negatively associated with alcohol use, even among college students, a group known to have high levels of alcohol consumption.

The positive relationship we found between normative influences and alcohol consumption is consistent with literature suggesting that peers are a prominent social influence regarding collegiate alcohol consumption (Chawla et al., 2007; Perkins, 2002). However, factors such as particular social networks, values, attitudes, coping processes, and the purpose and meaning in life may exacerbate or attenuate this association. For example, it may be that students who ascribe a high level of importance to religiousness maintain friendships with others who also hold religiousness in high regard, creating a circle of influence that is different from those students whose close peers do not hold religiousness as important. Chawla et al. (2007) found religiousness to be more negatively associated with perceived approval of drinking of friends and family members than of other college students. Students who place high importance on religion do consume less alcohol despite being in an environment where drinking is a normative behavior (i.e., undergraduate college attendance; O'Malley and Johnston, 2002), suggesting that not only do these students identify with different peers, but they also hold the opinions and injunctive norms of those peers as a source of reference.

In addition, Galen and Rogers (2004) suggest that religion reduces alcohol consumption via cognitive beliefs about alcohol. By instilling negative expectancies toward alcohol use, religion indirectly diminishes the motivation to drink. It is important to note that variance in religious institutions' attitudes toward alcohol use exists, with some requiring strict abstinence (e.g., Mormon, Islam, and more conservative Protestant denominations) and others having no restrictions but promoting healthy and controlled behaviors (e.g., Catholicism and Eastern religions). It is also possible that particular characteristics of these various religious perspectives may contribute to differences in the relationship among perceived norms, religiousness, and alcohol consumption.

The present research was framed around the question of whether religiousness might moderate the association between perceived norms and drinking. But, given the symmetry of the interactions, our results could equally support a model wherein perceived norms function as a moderator of the association between religiousness and drinking. If interpreted this way, the results would suggest that the negative association between religiousness and drinking is stronger when accompanied by higher perceived norms. In other words, the protective effect of religiousness on drinking appears to be particularly evident when individuals perceive drinking to be more prevalent among their peers. This might suggest that religiousness is more relevant and protective in the face of temptation or contexts that promote risky behavior.

Koenig and colleagues (Koenig, 2008; Koenig et al., 2012) present a model of the association between religion and health suggesting several functions of religion with respect to health. Three of these seem directly relevant to the present results. First, religion provides specific directions regarding behavior. As noted, most religions have specific prohibitions against excessive drinking. Second, religious involvement is associated with social connections that offer greater quantity and quality of social support, which would likely increase one's ability to resist engaging in prohibited behavior. Third, religion is a major source of coping, providing meaning, and offering hope and comfort, especially when dealing with difficult circumstances or temptations.

Implications

The results of the present study highlight the importance of understanding the protective factors of religiousness with regard to peer influences toward drinking. Perceived norms represent one type of peer influence and additional work is needed to evaluate whether discrepancies between perceived norms and actual norms may vary as a function of religiousness. In addition, peer selection, reference group goals and values, personal attitudes and expectations, and the purpose of life should be explored in greater detail when developing problem-drinking intervention and reduction strategies. Understanding these aspects of religion may help identify those who are at greater risk for problem drinking and who are more susceptible to peer influences.

Most empirically supported strategies for intervening with heavy drinking college students have incorporated feedback about social norms (Carey et al., 2007; Larimer and Cronce, 2007; Walters and Neighbors, 2005) and this component has been shown to mediate efficacy of multicomponent interventions (e.g., Borsari and Carey, 2000). Personalized normative feedback alone has also been shown to measurably reduce drinking among heavy drinkers for up to 2 years (Neighbors et al., 2004, 2010). Group-based live interactive norms feedback has also been effective in reducing group-specific normative misperceptions and subsequent drinking (Killos et al., 2010; LaBrie et al., 2008). The present results suggest that incorporation of content related to religious values may be a useful addition to existing intervention approaches, particularly with individuals whose current drinking behavior is discrepant from their religious values. For example, feedback regarding religious values might be provided and discussed in the context of their protective effects on problematic drinking (e.g., “You mentioned that it is very important to you to believe in God and to rely on religious teaching when you have a problem. These values have been consistently associated with lower likelihood of abusing alcohol.”). Alternatively, or in addition, feedback about religious values might be discussed in the context of norms feedback and reducing social influences on drinking (e.g., “You mentioned that it is very important to you to believe in God and to rely on religious teaching when you have a problem. These values have been associated with a greater ability to resist peer influences on drinking. Why do you think that might be?”). Furthermore, for interventions in which alcohol-free activities are discussed in the context of reducing drinking, emphasizing religious activities may be particularly useful.

Limitations and future directions

The findings of this study should be considered in the light of several limitations. First and foremost, the cross-sectional design of the study limits inferences regarding causal direction. In this study, the relatively small association between religiousness and perceived norms and their independent associations with drinking do not suggest a strong causal relationship between them, making causal direction less of a point of debate. However, the direction of potential causal associations between religiousness and drinking and between perceived norms and drinking are unclear. With regard to the former, previous longitudinal research suggests evidence for prospective associations between religiousness and subsequent drinking (Koenig et al., 2012). With respect to the latter, both causal directions have received previous support in longitudinal research, with perceived norms predicting subsequent drinking and drinking predicting subsequent perceived norms (Neighbors et al., 2006). In sum, additional longitudinal research is needed to more clearly establish temporal precedence of religiousness, perceived norms, and drinking.

The measures used in this research were also limited. Two of the drinking outcomes were assessed with single items. In addition, religious values were measured with a single four-item scale. Religiousness is extremely complex and multifaceted as demonstrated by the Hill and Hood (1999) compendium of 126 measures of religiousness (see also Fetzer Institute, 1999). Even in the health domain, Hill and Pargament (2003) identified multiple constructs related to religiousness including closeness to God, religion and spirituality as orienting and motivating forces, religious support, and religious and spiritual struggle. The measure used in the present study is conceptually similar to Allport and Ross' (1967) construct of intrinsic religiousness. Future studies should use multidimensional models of religiousness including the type of motivation for religious involvement.

Another limitation is that we did not assess religious affiliation. We were primarily interested in religious values per se, without respect to a specific religion or denomination. In retrospect, we recognize that there may be important differences across specific religions and denominations. For example, some religions/denominations explicitly prohibit alcohol use. To better understand the effect religion has as a moderator of alcohol use and perceived norms, religious affiliation should also be addressed in the future. Specifically, future studies should examine the differences and similarities found across religions and denominations. For example, previous research examining denominational differences has found that Catholics drink the most, Jews drink the least, and Muslims drink less than Christians or Hindus (Koenig et al., 2012). Perceived drinking norms might also vary by denomination. In addition, we might expect that the moderating effect of religiousness on the association between perceived norms and drinking would be more evident in some denominations than others. Exclusive reliance on self-report is another limitation that creates possible social desirability bias. Further, the sample consisted of college students who just turned 21 and were from one large university in the Northwest, which may limit the generalizability. Religious beliefs among college students might vary by geographical region. It would be useful to examine whether these findings hold in more regions of the country with higher levels of religious values. Finally, the large sample size resulted in even small associations being significant and small associations might represent type I errors.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the literature on the protective influence religiousness exerts on alcohol use and peer influences. Future studies may elucidate this relationship by further operationalizing the construct of religiousness, and by pairing the participant to his/her family's religiousness and behaviors concerning alcohol use. Longitudinal studies focusing on pre- and post-college drinking and on transitional behaviors in relation to religiousness and spirituality could further enhance our understanding of the relationship between the importance of religion and drinking behavior across adulthood.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R01AA016099, R01AA014576, and F31AA020442.

References

- Abrams D, Hogg MA. Social identity and social cognition. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW, Ross JM. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1967;5:432–443. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.5.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Student factors: Understanding individual variation in college drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14(Supplement):40–53. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr SJ, Maughan SL, Marcos AC, Li B. Family, religiosity, and the risk of adolescent drug use. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1998;60:979–992. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Stoneman Z, Flor D. Parental religiosity, family processes, and youth competence in rural, two-parent African American families. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:696–706. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TL, Salsman JM, Brechting EH, Carlson CR. Religiousness, spirituality, and social support: How are they related to underage drinking among college students? Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2008;17:15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Button TMM, Hewitt JK, Rhee SH, Corley RP, Stallings MC. The moderating effect of religiosity on the genetic variance of problem alcohol use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1619–1624. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla N, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Larimer ME. Attitudes and perceived approval of drinking as mediators of the relationship between the importance of religion and alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:410–418. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute. Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/ spirituality for use in health research: A report of the Fetzer Institute/ National Institute on Aging working group, with additional psychometric data. Kalamazoo, MI: Author; 1999. Retrieved from http://www.fetzer.org/resources/multidimensional-measurement-religiousnessspirituality-use-health-research. [Google Scholar]

- Galen LW, Rogers WM. Religiosity, alcohol expectancies, drinking motives and their interaction in the prediction of drinking among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:469–476. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Hood RW., Jr . Measures of religiosity. Birmingham, AL: Religious Education Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Pargament KI. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality. Implications for physical and mental health research. The American Psychologist. 2003;58:64–74. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TJ, Sheets VL, Kristeller JL. Identifying mediators of the relationship between religiousness/spirituality and alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:160–170. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2011. Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–50. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Killos LF, Hancock LC, Wattenmaker McGann A, Keller AE. Do “Clicker” educational sessions enhance the effectiveness of a social norms marketing campaign? Journal of American College Health. 2010;59:228–230. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.497830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Medicine, religion, and health: Where science and spirituality meet. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, King DE, Carson VB. Handbook of religion and health. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, Pedersen ER. Live interactive group-specific normative feedback reduces misperceptions and drinking in college students: A randomized cluster trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:141–148. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Gender-specific misperceptions of college student drinking norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:334–339. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczak SE, Corbett K, Oh C, Carr LG, Wall TL. Religious influences on heavy episodic drinking in Chinese-American and Korean-American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:467–471. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menagi FS, Harrell ZAT, June LN. Religiousness and college student alcohol use: Examining the role of social support. Journal of Religion and Health. 2008;47:217–226. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Atkins DC, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Kaysen D, Mittmann A, Rodriguez LM. Event-specific drinking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:702–707. doi: 10.1037/a0024051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Neil TA. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:290–299. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Desai S, Larimer ME. Group identification as a moderator of the relationship between perceived social norms and alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:522–528. doi: 10.1037/a0019944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonnemaker JM, McNeely CA, Blum RW. Public and private domains of religiosity and adolescent health risk behaviors: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57:2049–2054. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Hutchinson GT, Cheong J, Nagoshi CT. Effect of religion and religiosity on alcohol use in a college student sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;49:81–88. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice DA, Miller DT. Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:243–256. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MB, Lange JE, Ketchie JM, Clapp JD. The relationship between social identity, normative information, and college student drinking. Social Influence. 2007;2:269–294. [Google Scholar]

- Suls J, Green P. Pluralistic ignorance and college student perceptions of gender-specific alcohol norms. Health Psychology. 2003;22:479–486. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry DJ, Hogg MA. Group norms and the attitude-behavior relationship: A role for group identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22:776–793. [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Neighbors C. Feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: What, why and for whom? Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1168–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Yaeger AM, Sandy JM. Buffering effect of religiosity for adolescent substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:24–31. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]