Abstract

Gastrins, including amidated (Gamide) and glycine-extended (Ggly) forms, function as growth factors for the gastrointestinal mucosa. The p-21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) plays important roles in growth factor signaling networks that control cell motility, proliferation, differentiation, and transformation. PAK1, activated by both Gamide and Ggly, mediates gastrin-stimulated proliferation and migration, and activation of β-catenin, in gastric epithelial cells. The aim of this study was to investigate the role of PAK1 in the regulation by gastrin of proliferation in the normal colorectal mucosa in vivo. Mucosal proliferation was measured in PAK1 knockout (PAK1 KO) mice by immunohistochemistry. The expression of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of the signaling molecules PAK1, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and protein kinase B (AKT), and the expression of β-catenin and its downstream targets c-Myc and cyclin D1, were measured in gastrin knockout (Gas KO) and PAK1 KO mice by Western blotting. The expression and activation of PAK1 are decreased in Gas KO mice, and these decreases are associated with reduced activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin. Proliferation in the colorectal mucosa of PAK1 KO mice is reduced, and the reduction is associated with reduced activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin. In compensation, antral gastrin mRNA and serum gastrin concentrations are increased in PAK1 KO mice. These results indicate that PAK1 mediates the stimulation of colorectal proliferation by gastrins via multiple signaling pathways involving activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin.

Keywords: glycine-extended gastrin, colon

the growth-promoting effects of gastrins, including amidated (Gamide) and glycine-extended (Ggly) forms, in the gastrointestinal mucosa have been well documented (15). Previous studies have demonstrated that gastrins function as autocrine growth factors for colon-derived cell lines in vitro (3, 23) and in the colorectal mucosa in vivo (3, 27, 41). Proliferation in the colonic mucosa was decreased in gastrin knockout (Gas KO) mice but increased in mice overexpressing progastrin or Ggly (27, 28, 41). Similarly, exogenous Ggly stimulated proliferation of the defunctioned rectal mucosa in rats after colostomy (3). Importantly, gastrins have also been implicated in the development of colorectal carcinoma. Mice overexpressing gastrins developed more aberrant crypt foci in response to the chemical carcinogen azoxymethane than their wild-type littermates (12, 36), and the number of aberrant crypt foci in response to azoxymethane was also increased in rats infused with Ggly (3). Although a previous report showing that the transition from a normal to a hyperproliferative colonic epithelium in gastrin-overexpressing mice was associated with upregulation of several signaling molecules, including the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) and extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) (14) in the colonic mucosa (16), it is unclear how gastrins activate these signaling pathways.

The p-21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1), which is the best-characterized downstream effector of the small GTPases Rac and Cdc42 of the Rho family, plays important roles in a variety of signaling pathways involved in cell motility, proliferation, differentiation, and survival (5, 7, 39). In addition to activation by Rac/Cdc42, PAK1 activity can also be stimulated by other signaling molecules, including PI3K (39), 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (26), and AKT (37). PAK1 functions as a node involved in the activation of multiple signaling molecules, including ERK and β-catenin (6, 18, 24, 32, 35, 44), and mediates the effects of many growth factors. For example, heregulin, a member of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) family, stimulated the migration, invasiveness, and anchorage-independent growth of breast cancer cells by enhancing PAK1 activation (1, 2, 40). Hepatocyte growth factor induces epithelial cell scattering and migration through stimulating the phosphorylation and activation of PAK1 (8).

PAK1 also mediates the stimulatory effects of gastrins in gastrointestinal cells. We have shown that both Gamide and Ggly stimulate PAK1 activity in gastric epithelial cells, and PAK1 activation is required for gastrin-stimulated cell proliferation and migration, and activation of β-catenin (19, 20). These findings indicate that PAK1 mediates gastrin-stimulated cell proliferation and migration, and this mediation is in part via activation of the β-catenin pathway. However, the in vivo role of PAK1 in gastrin-regulated proliferation in the colorectal mucosa has not been investigated.

Recently, we have shown that a reduction of PAK1 expression in colon cancer cells decreased cell proliferation and migration/invasion both in vitro and in vivo and that this decrease was associated with reduced activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin (18, 24). Taken together our findings suggest that gastrins stimulate cell proliferation and migration by activation of PAK1, which in turn activates multiple signaling pathways, including ERK, AKT, and β-catenin. Although PAK1 is overexpressed and hyperactivated in gastric and colon cancer (9, 31), in vivo studies on the role of PAK1 in normal colon proliferation and its connection to gastrins have not been reported. The aim of this study was to investigate the role of PAK1 in the regulation by gastrin of the proliferation of colorectal mucosa in mouse models in which gastrin or PAK1 expression had been abrogated. Using Gas KO and PAK1 knockout (PAK1 KO) mice, the activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin, as well as the proliferation of colorectal mucosa, has been determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

All mouse experiments were approved by the Austin Health Animal Research Ethics Committee. Gas KO C57Bl6 and wild-type C57Bl6 mice were sex matched, and 6–10 mice of each experimental group (10–20 wk old) were used in this study. PAK1 KO FVB/N and wild-type FVB/N mice were also sex matched, and 6–10 mice in each group were used. Mice were maintained under standard conditions on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with free access to water and food.

Isolation of colonic epithelial cells and western blot analysis.

Colonic epithelial cells were isolated as previously described (30). Mice colonic cells were isolated by shaking the entire everted colon and rectum in a buffer containing 2.5 mM EDTA and 0.24 M NaCl at 4°C overnight. Cells were lysed, and lysates were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred to Hybond-C-Extra nitrocellulose (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and blotted with antibodies against either phospho-PAK1, total PAK1, phospho-ERK, total ERK, phospho-AKT, total AKT, β-catenin, c-myc, cyclin D1, or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The anti-phospho-PAK1 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and the remaining antibodies were from Cell Signal (Genesearch, Melbourne, Australia). Band densities were quantified by densitometric analysis using Multigauge software (Fujifilm Medical Systems, Stamford, CT). GAPDH concentrations were used to correct for equal protein loading on gels.

Measurement of colorectal proliferation in the mouse model.

Ten-week-old PAK1 KO and wild-type FVB/N mice were weighed before death and anesthetized by Forthane (isoflurane) inhalation before blood was collected by cardiac puncture. Colons and rectums were harvested, fixed, and paraffin embedded according to standard protocols. Sections of colon tissue were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to visualize the crypts for measurement of crypt height. Proliferation in the colorectal mucosa was also measured by staining for the nuclear protein Ki67 using anti-Ki67 antibody (Dakocytomation, Sydney, Australia).

Gastrin radioimmunoassay.

The concentrations of Gamide and Ggly in serum and tissue extracts from stomach and colon of 10-wk-old PAK1 KO and wild-type FVB/N mice were measured by radioimmunoassay as described previously (11). Region-specific gastrin antisera were used to measure Gamide (antiserum 1296) and Ggly (antiserum 7270). The cross-reactivity of antiserum 7270 for Gamide is 0.07.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

To determine the concentration of gastrin mRNA, the total RNA from the stomach of PAK1 KO and wild-type mice was extracted with TRizol (Invitrogen, Melbourne, Australia) and converted to cDNA using the Superscript III first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen). The resulting cDNA transcripts were used for real-time PCR amplification with the ABI 7700 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Melbourne, Australia) and Taqman chemistry according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primer pairs for gastrin were 5′-CCG CAG TGC TGA AGA TGA G-3′ and 5′-GGA GGT GGC TAG GCT CTG AA-3′ (29). Results were normalized to 18S RNA expression.

Stomach pH.

Mice were fasted overnight before death. The whole mouse stomach was dissected, and the contents were flushed into a 5-ml tube with 2 ml saline. The pH of the stomach contents was measured with a pH meter.

Cell-based assays.

PAK1 knockdown and negative control clones of the human colon cancer cell line DLD1 were obtained as described previously by transfection with plasmid DNAs encoding a short-hairpin RNA sequence to silence the PAK1 gene specifically, or with a scrambled sequence, respectively (24). A simplified nomenclature is used in this paper, such that NC1 = previous NC13; NC2 = previous NC14; PAK1 KD1 = previous IS2.23; and PAK1 KD2 = previous IS2.11. The clones tested negative for mycoplasma and were cultured in RPMI medium or DMEM containing 5% FBS.

Cell proliferation was assayed by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well in growth medium containing 5% FBS, and cultured at 37°C, followed by 24 h serum starvation. The cells were then treated with 10 nM Gamide (Auspep, Melbourne, Australia) or Ggly (Auspep) in RPMI or DMEM containing 1% FBS and 10 μCi/ml [3H-methyl]thymidine for the time indicated in the text, and then collected with a cell harvester (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). The amount of [3H]thymidine incorporated through DNA synthesis was detected with a β-counter (Packard, Meriden, CT).

Cell migration/invasion was determined using a modified Boyden Chamber assay (25). Membranes (8 μm pore; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) were coated with 3 μg human fibronectin on the lower surfaces and placed in a 24-well plate containing 600 μl/well of serum-free RPMI with 0.1% BSA. Cells (2–5 × 104·100 μl−1·chamber−1) were added to the upper chambers and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere with or without gastrins (10 nM). The cells on the upper surface of the membranes were removed by wiping with a cotton swab before the membranes were fixed and stained with Quick-Dip (Fronine, Sydney, Australia). The cells that migrated to the lower surface of the membranes were counted in 24 fields at 20 times magnification using a NIKON Coolscope (Coherent Scientific, Adelaide, Australia).

Statistical analysis.

All statistics were analyzed by t-tests with Bonferroni's correction with the program SigmaStat (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA). The results are expressed as means + SE, and the statistical significance at P < 0.01 and P < 0.05 is indicated.

RESULTS

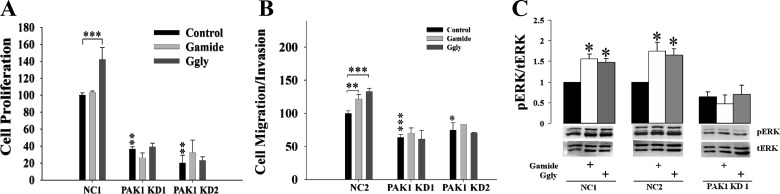

Gas KO mice have reduced proliferation in the colorectal mucosa (28), and hyperproliferation in the colorectal mucosa of mice overexpressing gastrins is associated with upregulation of signaling molecules, including AKT and ERK (16). In gastric epithelial cells, both Gamide and Ggly stimulate PAK1 activity, leading to the activation of β-catenin, and increased cell proliferation and migration (19). PAK1 enhances colon cancer cell growth by activation of multiple signaling molecules, including ERK, AKT, and β-catenin (18, 24). Furthermore, gastrin-stimulated cell proliferation, migration, and ERK activation in the human colorectal cancer cell line DLD1 are blocked by PAK1 knockdown (Fig. 1). These observations suggested the hypothesis that gastrins stimulate the proliferation of the colorectal mucosa by activation of PAK1, which in turn activates multiple signaling molecules.

Fig. 1.

p-21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) knockdown blocked gastrin-stimulated proliferation, migration, and activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in colorectal cancer cells. The human colorectal cancer cell line DLD1 was transfected with PAK1 short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) to knockdown PAK1 protein expression as described in a previous report (24). Both negative control (NC, transfected with a scrambled sequence) and PAK1 knockdown (PAK1 KD) cells were stimulated with or without amidated gastrin [Gamide (10 nM)] or glycine-extended gastrin [Ggly (10 nM)] for 24 h in 1% FBS (for proliferation and ERK activation) or 1% BSA (for migration). Cell proliferation (A) and migration (B) were measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation and Boyden chamber assay, respectively (24). The phosphorylated and active ERK (pERK) and total ERK (tERK) were measured by Western blot (C). Data are summarized from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

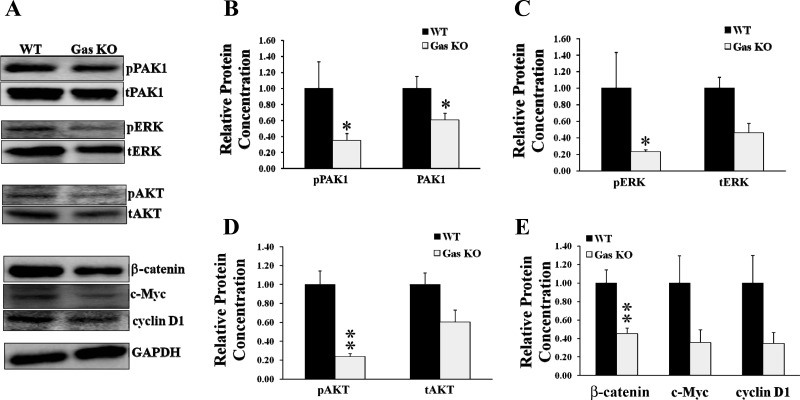

Activation of PAK1, ERK, AKT, and β-catenin is decreased in the colorectal mucosa of Gas KO mice.

To investigate the role of PAK1 in the proliferative effects of gastrins in vivo, the expression and activation of PAK1, ERK, AKT, and β-catenin in the colorectal mucosa of both wild-type (26) and Gas KO mice were determined by Western blotting. Expression was measured with antibodies against the total protein, and activation in the case of PAK1, ERK, and AKT with antibodies against the phosphorylated protein, and in the case of β-catenin with antibodies against the downstream targets c-Myc and cyclin D1. In the colon of Gas KO mice, both activation and expression of PAK1 were decreased to 40 or 60%, respectively, of the value for wild-type mice (Fig. 2, A and B). The activation of ERK and AKT was also decreased in the colon of Gas KO mice (Fig. 2, A, C, and D). The decreased activation of PAK1, ERK, and AKT was likely the result of the reduction in the expression of total PAK1, ERK, and AKT, since the ratios of phosphorylated to total proteins were not changed significantly between wild-type and Gas KO mice (data not shown). The expression of β-catenin in the colon of Gas KO mice was significantly reduced to 40% of the value for wild-type mice (Fig. 2, A and E). The expression of c-Myc and cyclin D1, the downstream targets of activation of β-catenin, was decreased to a similar degree, although additional samples will be needed to reach statistical significance. These results indicate that the decreased proliferation in the colorectal mucosa in Gas KO mice is associated with downregulation of multiple signaling molecules, including PAK1, ERK, AKT, and β-catenin, and hence suggest that gastrins regulate colorectal proliferation via multiple signaling pathways.

Fig. 2.

Activation of PAK1, ERK, protein kinase B (AKT), and β-catenin was reduced in gastrin knockout (Gas KO) mice. Epithelial cells were isolated from the colorectal mucosa of both Gas KO and wild-type (WT) mice, and the activation of PAK1, ERK, AKT, and β-catenin was determined by Western blots as described in materials and methods. Activation of PAK1, ERK, and AKT was measured by Western blotting for phosphorylated PAK1 (pPAK1), ERK (pERK), and AKT (pAKT). Activation of β-catenin was determined by measurement of the expression of β-catenin, c-Myc, and cyclin D. A: representative protein blots. tAKT, total AKT. B–E: data summarized from the blots of samples from 6–8 WT or Gas KO mice. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

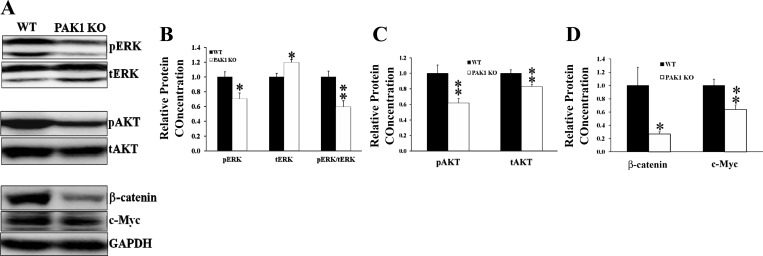

Activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin is decreased in the colorectal mucosa of PAK1 KO mice.

PAK1 is required for gastrin-stimulated activation of β-catenin (19). PAK1 also activates both ERK and AKT in breast cancer and colorectal cancer cells (4, 24, 32, 35). Therefore, PAK1 could mediate the stimulation of colorectal proliferation by gastrins via multiple signaling molecules, including ERK, AKT, and β-catenin. The decreased colorectal proliferation in Gas KO mice was associated with reduced activation of PAK1, ERK, AKT, and β-catenin. If PAK1 acts upstream of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin, a reduction in PAK1 activity would be expected to cause a reduction in the activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin. Indeed the activation of both ERK (phosphorylated ERK) and AKT (phosphorylated AKT) was significantly decreased in the colorectal mucosa of PAK1 KO mice when compared with their wild-type littermates (Fig. 3, A–C). The ratio of phosphorylated ERK to total ERK was reduced in the colorectal mucosa of PAK1 KO mice (Fig. 3, A and B), although there was an increment in the total amount of ERK possibly as compensation for the decreased activation of ERK. The decreased activation of AKT was the result of the reduced expression of total AKT, since the ratio of phosphorylated to total protein was not changed significantly between wild-type and PAK1 KO mice (data not shown). Similarly, the expression of β-catenin and c-Myc was also reduced significantly in the colorectal mucosa of PAK1 KO mice (Fig. 3, A and D). These data indicate that PAK1 is required for the activation of multiple signaling molecules such as ERK, AKT, and β-catenin, all of which contribute to proliferation in the colorectal mucosa.

Fig. 3.

Activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin was reduced in PAK1 knockout (PAK1 KO) mice. Epithelial cells were isolated from the colorectal mucosa of both PAK1 KO and WT mice, and activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin was determined by Western blotting for pERK and pAKT. Activation of β-catenin was determined by measurement of the expression of β-catenin and c-Myc. A: representative protein blots. B–D: summarized from the blots of samples of 6–8 WT or PAK1 KO mice. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

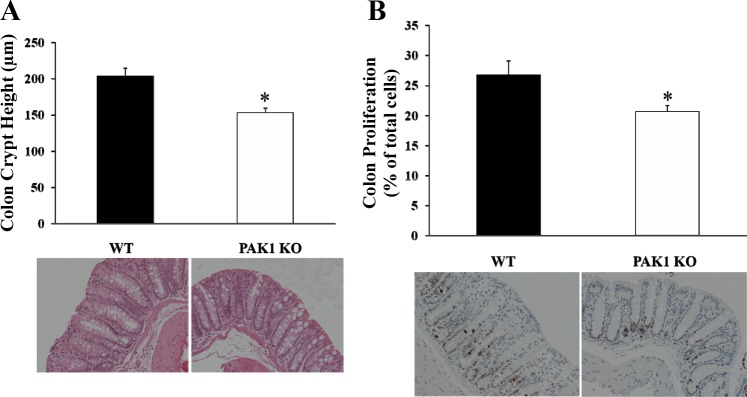

Proliferation of colorectal mucosa was reduced in PAK1 KO mice.

Because PAK1 KO mice had significantly reduced activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin in the colorectal mucosa, proliferation in the colorectal mucosa was investigated. The colons and rectums were dissected from both wild-type and PAK1 KO mice (10 wk old), fixed, and stained as described in materials and methods. Proliferation in the colorectal mucosa was determined by measurement of crypt height and by nuclear staining for the protein Ki67. The colonic crypt height in PAK1 KO mice was reduced to 75% of the value in wild-type littermates (Fig. 4A). Cell proliferation, represented by Ki67 staining, in the colorectal mucosa of PAK1 KO mice was also decreased by ∼25% compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that PAK1 KO reduced proliferation in the colorectal mucosa, most likely by suppressing the activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin.

Fig. 4.

Proliferation in the colorectal mucosa was decreased in PAK1 KO mice. The colons from both WT and PAK1 KO mice were dissected, fixed, and stained as described in materials and methods. Colonic crypts were visualized by hematoxylin and eosin staining, and the crypt height was measured under the microscope at 20 times magnification (A). Proliferation was determined as the ratio of Ki67-stained cells to the total cells counted per field under the microscope (B). Results are summarized from 6–8 WT or PAK1 KO mice. *P < 0.05.

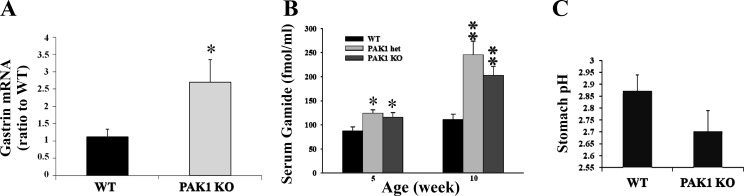

Gastrins were increased in PAK1 KO mice.

The observation that Gas KO mice had reduced expression and activation of PAK1 (Fig. 2, A and B) suggested that PAK1 was activated by gastrins. To determine the effect of PAK1 KO on gastrins, gastrin production in PAK1 KO mice was compared with wild-type littermates. The concentration of gastrin mRNA in the stomachs of PAK1 KO mice was 2.5-fold greater than in the stomachs of wild-type mice when measured by real-time PCR as described in materials and methods (Fig. 5A). The serum concentration of Gamide, the predominant regulated form of gastrin in serum, was significantly increased in both heterozygous (PAK1+/−) and homozygous PAK1 KO mice at 5 and 10 wk of age compared with the value for wild-type littermates (Fig. 5B). Hypergastrinemia was not the result of an increase in gastric pH, since the pH of the stomach contents from PAK1 KO mice was not significantly different from the value for their wild-type littermates (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that downregulation of PAK1 was associated with an increase in gastrin expression and secretion.

Fig. 5.

Gastrin production was increased in PAK1 KO mice. Gastrin mRNA from both WT and PAK1 KO stomach tissue was measured by real-time PCR (A). Gamide concentrations in the serum of WT, heterozygous (PAK1 het), and PAK1 KO mice were determined by radioimmunoassay (B). The pH of the stomach contents was measured in 16 WT and 11 PAK1 KO mice (C). Results (A and B) are summarized from 8–10 animals/group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Gastrins play important roles in colorectal proliferation, which is decreased in gastrin KO mice (28) but increased in gastrin-overexpressing mice (27). In this study, the mechanism of the regulation of colorectal proliferation by gastrins has been explored further. Gastrin-stimulated cell proliferation, migration, and ERK activation in the human colorectal cancer cell line DLD1 are blocked by PAK1 knockdown (Fig. 1). The activities of PAK1, ERK, AKT, and β-catenin are decreased in the colorectal mucosa of gastrin KO mice, and PAK1 KO also reduces the activities of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin. These results suggest that PAK1 is activated by gastrins and acts upstream of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin in vivo.

PAK1 mediates the effects of many growth factors on cellular events. Prolactin promotes mammary cell proliferation by activation of cyclin D1 through PAK1-dependent mechanisms (38). EGF stimulates the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer cells by upregulation of PAK1 and other signaling molecules (21). We have shown previously that PAK1 is activated by both Gamide and Ggly in gastric epithelial cells and that the activation of PAK1 is required for the stimulation by gastrins of cell proliferation and migration in vitro (19). Here we have demonstrated that gastrin KO mice had reduced expression and activity of PAK1 in the colorectal mucosa, whereas loss of function of PAK1 in PAK1 KO mice decreased colorectal proliferation. The observation that deletion of the gastrin gene decreased activation of PAK1 in the colorectal mucosa of gastrin KO mice (Fig. 2) indicates that gastrins activate PAK1 in vivo. Activation is required for colorectal proliferation, since knockout of PAK1 reduced proliferation of colorectal mucosa (Fig. 4). Thus we have identified for the first time a role for PAK1 in colorectal proliferation induced by gastrins in vivo.

PAK1, which acts as an oncogene in breast cancer, has previously been reported to coordinately regulate multiple signaling pathways, including RAF-MEK-ERK, leading to malignant transformation (35). PAK1-induced metastasis in gastric cancer involves activation of ERK and JUK (31). In breast cancer PAK1 is also required for growth factor-stimulated phosphorylation and activation of AKT, which contributes to cell survival (34). We have previously reported that PAK1 is required for gastrin-stimulated activation of β-catenin in vitro (19) and that inhibition of PAK1 by small-interfering RNA suppresses colorectal cancer cell growth by downregulation of the activities of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin signaling pathways (18, 24). Taken together these in vitro findings indicate that PAK1, acting as a node, regulates the downstream activation of multiple signaling molecules, such as ERK, AKT, and β-catenin, leading to cell growth and survival. This conclusion is consistent with the in vivo findings reported here that PAK1 acts upstream of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin.

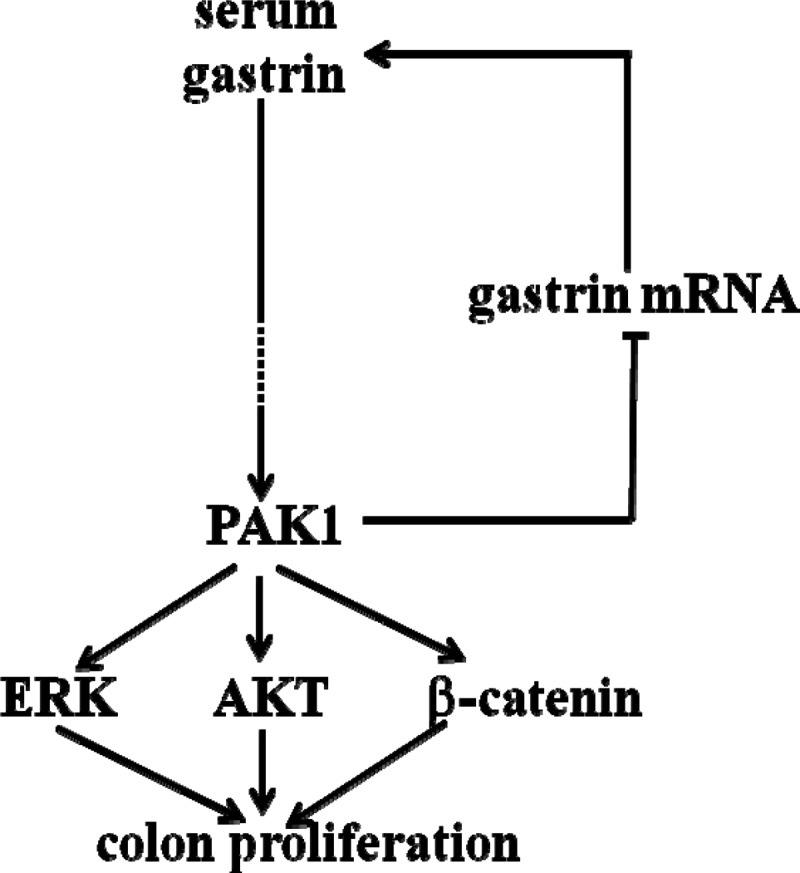

Activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin has been implicated in cell proliferation. In particular, the importance of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK and PI3K-AKT pathways in the stimulation of cell growth by growth factors has been identified by many workers. Platelet-derived growth factor activates both ERK- and AKT-dependent pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma, inducing cell proliferation and causing resistance to anti-cancer treatment (33). The synergetic effects between ERK- and AKT-dependent pathways in colon cancer growth make it necessary to use a combination of inhibitors to suppress both signaling pathways simultaneously (42). Similarly, the coactivation of both the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK and PI3K-AKT pathways in other human cancers and proliferative diseases has profound effects on targeted therapies (10). Activation of multiple signaling pathways, including ERK, AKT, and β-catenin, has been reported in colorectal (18, 24) and hepatocellular (43) carcinoma. PAK1 enhances colorectal cancer cell growth and metastasis by activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin (18, 24). Gastrins, including Gamide and Ggly, promote cell growth through regulation of the activities of PAK1, ERK, AKT, and β-catenin (13, 17, 19, 22). The fact reported here that, in both gastrin and PAK1 KO mice, decreased activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin in the colorectal mucosa was associated with reduced proliferation suggests that activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin is involved in colorectal proliferation in vivo. Taken together our data suggest that gastrins activate PAK1, which in turn enhances colorectal proliferation by regulating the activities of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

PAK1 mediates gastrin-stimulated proliferation in the colorectal mucosa via multiple signaling molecules. Deletion of the gastrin gene resulted in a reduction in colorectal proliferation associated with decreased activation of PAK1, ERK, AKT, and β-catenin. Deletion of the PAK1 gene resulted in reduced colorectal proliferation associated with decreased activities of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin. PAK1 also negatively regulated gastrin production, since PAK1 KO mice had increased gastrin mRNA in the gastric mucosa and were hypergastrinemic. Together these results suggested that gastrins activate PAK1, which in turn enhances the activities of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin, and that the activation of these multiple signaling molecules contributes to proliferation in the colorectal mucosa.

Deletion of the PAK1 gene in PAK1 KO mice stimulated gastrin production. Concentrations of both gastrin mRNA in the stomach (Fig. 5A) and Gamide in the serum (Fig. 5B) were significantly increased in PAK1 KO mice. The increase in gastrin production was not because of modulation of feedback inhibition by gastric acid, since the pH of the stomach contents of PAK1 KO mice was not significantly different from wild-type littermates (Fig. 5C). The increased gastrin production in PAK1 KO mice suggests a feedback loop between PAK1 and gastrin production (Fig. 6), but further study will be needed to elucidate the mechanism involved. Regardless of the pathways involved, the observation that proliferation in the colorectal mucosa was reduced in PAK1 KO mice, even though the circulating concentration of Gamide was increased, indicates that loss of PAK1 function overrides the stimulation by gastrins of colorectal proliferation, and hence confirms that PAK1 is required for the stimulatory effects of gastrins.

In conclusion, both gastrin KO and PAK1 KO mice had decreased proliferation in the colorectal mucosa, and the decrease was associated with downregulation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin. Activation of PAK1 was also decreased in gastrin KO mice. These results indicate that gastrins stimulate PAK1 activity, which in turn enhances the activation of ERK, AKT, and β-catenin, leading to increased proliferation of colorectal mucosa. Identification of the role of PAK1 in the proliferative effects of gastrins in the colorectal mucosa in vivo reveals that the interaction of PAK1 with gastrins is a normal physiological process and that PAK1 may act as a key mediator of the effects of gastrins in colorectal cancer progression.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: N.H., M.Y., and H.H. performed experiments; N.H. and H.H. analyzed data; N.H. and H.H. prepared figures; J.C. and H.H. interpreted results of experiments; J.C., A.S., G.S.B., and H.H. approved final version of manuscript; A.S., G.S.B., and H.H. conception and design of research; A.S., G.S.B., and H.H. edited and revised manuscript; H.H. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Grants 454322 (G. S. Baldwin) and 508908 (H. He) and National Cancer Institute Grant R01 CA58836 (J. Chernoff).

REFERENCES

- 1. Adam L, Vadlamudi R, Kondapaka SB, Chernoff J, Mendelsohn J, Kumar R. Heregulin regulates cytoskeletal reorganization and cell migration through the p21-activated kinase-1 via phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase. J Biol Chem 273: 28238–28246, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adam L, Vadlamudi R, Mandal M, Chernoff J, Kumar R. Regulation of microfilament reorganization and invasiveness of breast cancer cells by kinase dead p21-activated kinase-1. J Biol Chem 275: 12041–12050, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aly A, Shulkes A, Baldwin GS. Short term infusion of glycine-extended gastrin(17) stimulates both proliferation and formation of aberrant crypt foci in rat colonic mucosa. Int J Cancer 94: 307–313, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arias-Romero LE, Chernoff J. p21-activated kinases in Erbb2-positive breast cancer: a new therapeutic target? Small Gtpases 1: 124–128, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arias-Romero LE, Chernoff J. A tale of two Paks. Biol Cell 100: 97–108, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arias-Romero LE, Villamar-Cruz O, Pacheco A, Kosoff R, Huang M, Muthuswamy SK, Chernoff J. A Rac-Pak signaling pathway is essential for ErbB2-mediated transformation of human breast epithelial cancer cells. Oncogene 29: 5839–5849, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bokoch GM. Biology of the p21-activated kinases. Annu Rev Biochem 72: 743–781, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bright MD, Garner AP, Ridley AJ. PAK1 and PAK2 have different roles in HGF-induced morphological responses. Cell Signal 21: 1738–1747, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carter JH, Douglass LE, Deddens JA, Colligan BM, Bhatt TR, Pemberton JO, Konicek S, Hom J, Marshall M, Graff JR. Pak-1 expression increases with progression of colorectal carcinomas to metastasis. Clin Cancer Res 10: 3448–3456, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chappell WH, Steelman LS, Long JM, Kempf RC, Abrams SL, Franklin RA, Basecke J, Stivala F, Donia M, Fagone P, Malaponte G, Mazzarino MC, Nicoletti F, Libra M, Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Mijatovic S, Montalto G, Cervello M, Laidler P, Milella M, Tafuri A, Bonati A, Evangelisti C, Cocco L, Martelli AM, McCubrey JA. Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR inhibitors: rationale and importance to inhibiting these pathways in human health. Oncotarget 2: 135–164, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ciccotosto GD, McLeish A, Hardy KJ, Shulkes A. Expression, processing, and secretion of gastrin in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterology 109: 1142–1153, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cobb S, Wood T, Ceci J, Varro A, Velasco M, Singh P. Intestinal expression of mutant and wild-type progastrin significantly increases colon carcinogenesis in response to azoxymethane in transgenic mice. Cancer 100: 1311–1323, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Daulhac L, Kowalski-Chauvel A, Pradayrol L, Vaysse N, Seva C. Ca2+ and protein kinase C-dependent mechanisms involved in gastrin-induced Shc/Grb2 complex formation and P44-mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. Biochem J 325: 383–389, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dehez S, Bierkamp C, Kowalski-Chauvel A, Daulhac L, Escrieut C, Susini C, Pradayrol L, Fourmy D, Seva C. c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase pathway in growth-promoting effect of the G protein-coupled receptor cholecystokinin B receptor: a protein kinase C/Src-dependent-mechanism. Cell Growth Differ 13: 375–385, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dockray GJ, Varro A, Dimaline R, Wang T. The gastrins: their production and biological activities. Annu Rev Physiol 63: 119–139, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ferrand A, Bertrand C, Portolan G, Cui G, Carlson J, Pradayrol L, Fourmy D, Dufresne M, Wang TC, Seva C. Signaling pathways associated with colonic mucosa hyperproliferation in mice overexpressing gastrin precursors. Cancer Res 65: 2770–2777, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferrand A, Kowalski-Chauvel A, Bertrand C, Pradayrol L, Fourmy D, Dufresne M, Seva C. Involvement of JAK2 upstream of the PI 3-kinase in cell-cell adhesion regulation by gastrin. Exp Cell Res 301: 128–138, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. He H, Huynh N, Liu KH, Malcontenti-Wilson C, Zhu J, Christophi C, Shulkes A, Baldwin GS. P-21 activated kinase 1 knockdown inhibits beta-catenin signalling and blocks colorectal cancer growth. Cancer Lett 317: 65–71, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. He H, Shulkes A, Baldwin GS. PAK1 interacts with beta-catenin and is required for the regulation of the beta-catenin signalling pathway by gastrins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1783: 1943–1954, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. He H, Yim M, Liu KH, Cody SC, Shulkes A, Baldwin GS. Involvement of G proteins of the Rho family in the regulation of Bcl-2-like protein expression and caspase 3 activation by Gastrins. Cell Signal 20: 83–93, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hipp S, Walch A, Schuster T, Losko S, Laux H, Bolton T, Hofler H, Becker KF. Activation of epidermal growth factor receptor results in snail protein but not mRNA overexpression in endometrial cancer. J Cell Mol Med 13: 3858–3867, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hollande F, Choquet A, Blanc EM, Lee DJ, Bali JP, Baldwin GS. Involvement of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinases in glycine-extended gastrin-induced dissociation and migration of gastric epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 276: 40402–40410, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hollande F, Imdahl A, Mantamadiotis T, Ciccotosto GD, Shulkes A, Baldwin GS. Glycine-extended gastrin acts as an autocrine growth factor in a nontransformed colon cell line. Gastroenterology 113: 1576–1588, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huynh N, Liu KH, Baldwin GS, He H. P21-activated kinase 1 stimulates colon cancer cell growth and migration/invasion via ERK- and AKT-dependent pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta 1803: 1106–1113, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishizu K, Sunose N, Yamazaki K, Tsuruo T, Sadahiro S, Makuuchi H, Yamori T. Development and characterization of a model of liver metastasis using human colon cancer HCT-116 cells. Biol Pharm Bull 30: 1779–1783, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. King CC, Gardiner EM, Zenke FT, Bohl BP, Newton AC, Hemmings BA, Bokoch GM. p21-activated kinase (PAK1) is phosphorylated and activated by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1). J Biol Chem 275: 41201–41209, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koh TJ, Dockray GJ, Varro A, Cahill RJ, Dangler CA, Fox JG, Wang TC. Overexpression of glycine-extended gastrin in transgenic mice results in increased colonic proliferation. J Clin Invest 103: 1119–1126, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koh TJ, Goldenring JR, Ito S, Mashimo H, Kopin AS, Varro A, Dockray GJ, Wang TC. Gastrin deficiency results in altered gastric differentiation and decreased colonic proliferation in mice. Gastroenterology 113: 1015–1025, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kovac S, Xiao L, Shulkes A, Patel O, Baldwin GS. Gastrin increases its own synthesis in gastrointestinal cancer cells via the CCK2 receptor. FEBS Lett 584: 4413–4418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Laburthe M, Chenut B, Rouyer-Fessard C, Tatemoto K, Couvineau A, Servin A, Amiranoff B. Interaction of peptide YY with rat intestinal epithelial plasma membranes: binding of the radioiodinated peptide. Endocrinology 118: 1910–1917, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li LH, Luo Q, Zheng MH, Pan C, Wu GY, Lu YZ, Feng B, Chen XH, Liu BY. P21-activated protein kinase 1 is overexpressed in gastric cancer and induces cancer metastasis. Oncol Rep 27: 1435–1442, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li LH, Zheng MH, Luo Q, Ye Q, Feng B, Lu AG, Wang ML, Chen XH, Su LP, Liu BY. P21-activated protein kinase 1 induces colorectal cancer metastasis involving ERK activation and phosphorylation of FAK at Ser-910. Int J Oncol 37: 951–962, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li QL, Gu FM, Wang Z, Jiang JH, Yao LQ, Tan CJ, Huang XY, Ke AW, Dai Z, Fan J, Zhou J. Activation of PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathway through a pdgfrbeta-dependent feedback loop is involved in rapamycin resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One 7: e33379, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Riaz A, Zeller KS, Johansson S. Receptor-specific mechanisms regulate phosphorylation of akt at ser473: role of rictor in beta1 integrin-mediated cell survival. PLoS One 7: e32081, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shrestha Y, Schafer EJ, Boehm JS, Thomas SR, He F, Du J, Wang S, Barretina J, Weir BA, Zhao JJ, Polyak K, Golub TR, Beroukhim R, Hahn WC. PAK1 is a breast cancer oncogene that coordinately activates MAPK and MET signaling. Oncogene 31: 3397–3408, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Singh P, Velasco M, Given R, Varro A, Wang TC. Progastrin expression predisposes mice to colon carcinomas and adenomas in response to a chemical carcinogen. Gastroenterology 119: 162–171, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tang Y, Zhou H, Chen A, Pittman RN, Field J. The Akt proto-oncogene links Ras to Pak and cell survival signals. J Biol Chem 275: 9106–9109, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tao J, Oladimeji P, Rider L, Diakonova M. PAK1-Nck regulates cyclin D1 promoter activity in response to prolactin. Mol Endocrinol 25: 1565–1578, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tsakiridis T, Taha C, Grinstein S, Klip A. Insulin activates a p21-activated kinase in muscle cells via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem 271: 19664–19667, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vadlamudi RK, Adam L, Wang RA, Mandal M, Nguyen D, Sahin A, Chernoff J, Hung MC, Kumar R. Regulatable expression of p21-activated kinase-1 promotes anchorage-independent growth and abnormal organization of mitotic spindles in human epithelial breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 275: 36238–36244, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang TC, Koh TJ, Varro A, Cahill RJ, Dangler CA, Fox JG, Dockray GJ. Processing and proliferative effects of human progastrin in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest 98: 1918–1929, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wee S, Jagani Z, Xiang KX, Loo A, Dorsch M, Yao YM, Sellers WR, Lengauer C, Stegmeier F. PI3K pathway activation mediates resistance to MEK inhibitors in KRAS mutant cancers. Cancer Res 69: 4286–4293, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Whittaker S, Marais R, Zhu AX. The role of signaling pathways in the development and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 29: 4989–5005, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhu G, Wang Y, Huang B, Liang J, Ding Y, Xu A, Wu W. A Rac1/PAK1 cascade controls beta-catenin activation in colon cancer cells. Oncogene 31: 1001–1012, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]