Abstract

This study examined the effect of substitution of a 2.4-megabase pair (Mbp) region of Brown Norway (BN) rat chromosome 1 (RNO1) between 258.8 and 261.2 Mbp onto the genetic background of fawn-hooded hypertensive (FHH) rats on autoregulation of renal blood flow (RBF), myogenic response of renal afferent arterioles (AF-art), K+ channel activity in renal vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and development of proteinuria and renal injury. FHH rats exhibited poor autoregulation of RBF, while FHH.1BN congenic strains with the 2.4-Mbp BN region exhibited nearly perfect autoregulation of RBF. The diameter of AF-art from FHH rats increased in response to pressure but decreased in congenic strains containing the 2.4-Mbp BN region. Protein excretion and glomerular and interstitial damage were significantly higher in FHH rats than in congenic strains containing the 2.4-Mbp BN region. K+ channel current was fivefold greater in VSMCs from renal arterioles of FHH rats than cells obtained from congenic strains containing the 2.4-Mbp region. Sequence analysis of the known and predicted genes in the 2.4-Mbp region of FHH rats revealed amino acid-altering variants in the exons of three genes: Add3, Rbm20, and Soc-2. Quantitative PCR studies indicated that Mxi1 and Rbm20 were differentially expressed in the renal vasculature of FHH and FHH.1BN congenic strain F. These data indicate that transfer of this 2.4-Mbp region from BN to FHH rats restores the myogenic response of AF-art and autoregulation of RBF, decreases K+ current, and slows the progression of proteinuria and renal injury.

Keywords: kidney, glomerulosclerosis, chronic renal failure, renal hemodynamics

the fawn-hooded hypertensive (FHH) rat is a genetic model of hypertension (33) that develops proteinuria, glomerulosclerosis (21, 30, 37, 47), and chronic kidney disease (22, 25–26, 41–42). We have previously reported that the development of proteinuria and glomerular injury in FHH rats is associated with an impaired autoregulation of renal blood flow (RBF), glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and glomerular capillary pressure (Pgc) (24, 40, 43, 48). Genetic cosegregation studies identified five quantitative trait loci (QTLs) linked to the development of proteinuria in F2 crosses of FHH and August-Copenhagen inbred (ACI) rats (4–5, 36). The rat chromosome (RN) regions are Rf-1 and Rf-2 on RNO1, Rf-3 on RNO3, Rf-4 on RNO14, and Rf-5 on RNO17. The Rf-1 QTL is of particular interest in that it lies within a region that is homologous to an area on human chromosome 10 linked to the development of diabetic nephropathy (19) and end-stage renal disease (18). More recent studies identified a G-to-A mutation in the start codon of Rab38, a gene in the Rf-2 QTL that influences protein trafficking and contributes to the development of proteinuria in FHH rats (32). However, the genes in the Rf-1 region that contribute to the development of proteinuria and renal disease in FHH rats and the mechanisms involved are unknown.

We have previously reported that substitution of a 99.4-megabase pair (Mbp) region of RNO1 from Brown Norway (BN) into FHH rats, encompassing the Rf-2 locus from markers D1Rat183 to D1Rat76, along with a 12.9-Mbp region in the Rf-1 region of RNO1 (strain B, see Fig. 1) restored autoregulation of RBF and reduced proteinuria in this FHH.1BN double congenic strain (24). In contrast, autoregulation of RBF was not restored in a congenic strain in which only the 99.4-Mbp region of RNO1 containing the Rf-2 region was introgressed. Subsequently, we developed a subcongenic strain that narrowed the region of interest for autoregulation of RBF from 12.9 to a smaller 4.7-Mbp region of RNO1 (48). However, this region was still too large for positional cloning of the genes involved, and studies using this double congenic strain are open to the criticism that the restoration of the RBF autoregulation phenotype could be due to an interaction of genes in the two independent introgressed regions of BN RNO1. Thus the purpose of the present study was first to narrow the region of interest by creating and phenotyping two new FHH.1BN double congenic strains, D and E (genotypes presented in Fig. 1), and then to create and phenotype a minimal FHH.1BN congenic, strain F, in which only the small region of BN RNO1 near the Rf-1 QTL was introgressed onto the FHH genetic background. We also compared the myogenic response of isolated, perfused afferent arterioles obtained from FHH and the new FHH.1BN congenic strains E and F and performed expression and sequence analysis on all the genes in the region. Finally, as the development of a myogenic response is critically dependent on membrane potential and inhibition of the opening of large-conductance calcium-activated potassium (BKCa) channels, we performed patch-clamp studies to assess K+ channel activity in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) isolated from renal arterioles obtained from FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strains.

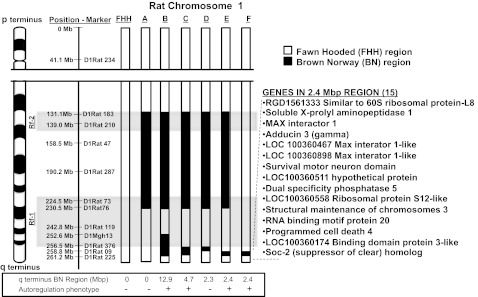

Fig. 1.

Genetic map of regions of Brown Norway (BN) chromosome 1 in FHH.1BN congenic strains. Fawn hooded hypertensive rat (FHH) regions are presented in white, and BN regions are presented in black. The left side of the figure indicates some of the polymorphic markers used to genotype the strains. The limits of the previously reported renal failure QTL regions, Rf-1 and Rf-2, are highlighted in gray. Currently, there are 15 known and predicted genes in the 2.4-Mbp region of interest. The official Rat Genome nomenclature for strains are as follows: strain A = FHH.1BN-(D1rat183-D1rat76), strain B = FHH.1BN-(D1rat183-D1rat76;D1Mgh13-D1Rat89), strain C = FHH.1BN-(D1rat183-D1rat76;D1Rat376-D1Rat225), strain D = FHH.1BN-(D1rat183-D1rat76;D1Rat376-D1Rat09), strain E = FHH.1BN-(D1rat183-D1rat76;D1Rat09-D1Rat225), strain F = FHH.1BN-(D1Rat09-D1Rat225).

METHODS

General

Experiments were performed in ∼200 male FHH and FHH.1BN congenic rats (9–21 wk old) bred and maintained at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, which is fully accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Mississippi Medical Center. The rats had free access to food and water. After weaning, the rats were maintained on purified AIN-76 rodent diet containing 0.4% NaCl (Dyets, Bethlehem, PA).

Protocol 1: Generation of Subcongenic Strains from FHH.1BN Congenic Strain C

In previous studies, we found that autoregulation of RBF is impaired in FHH rats and transfer of a 4.7-Mb region of RNO1 from BN rats in a FHH.1BN double congenic, presented here as strain C in Fig. 1, restored autoregulation (48). The goal of the present study was to create additional double subcongenic strains to narrow the region of interest further so that positional candidate genes could be prioritized by sequencing and expression studies.

Three male FHH.1BN congenic strain C rats were backcrossed with six female rats from the FHH.1BN congenic strain A to generate an F1 generation, heterozygous for the region of interest and homozygous for BN alleles in the RF-2 region and FHH alleles across the remainder of the genome. From this F1 colony, 18 breeding pairs were set up to generate F2 rats. Each of the F2 animals was genotyped by PCR with a set of 30 polymorphic microsatellite markers equally spaced across the 4.7-Mbp region of interest. The genetic distance across the original region was 4.7 Mbp, which corresponds to a 5% recombinant frequency, and ∼700 F2 rats were genotyped to identify the founders for the two new subcongenic lines. The heterozygous founders were backcrossed to FHH.1BN control congenic line A to retain the 99.4-Mbp BN region on RNO1, and the heterozygous progeny were intercrossed to obtain homozygous animals for the two new subcongenic strains D and E.

After narrowing the region of interest by phenotyping strains D and E for autoregulation of RBF relative to the original double congenic strain C and a control FHH.1BN congenic strain A that retains the common 99.4-Mbp region (131.1–230.5 Mbp) of BN RNO1 encompassing the Rf-2 region including the Rab38 gene known to prevent bleeding (8) and restore proximal tubular reabsorption of protein (32), we generated a minimal congenic strain to eliminate the possibility that gene-gene interactions are responsible for the restoration of the RBF autoregulation phenotype. This was accomplished by crossing FHH.1BN congenic strain E with FHH rats. The F1 heterozygous rats were intercrossed, and the F2 population was genotyped to find pairs of animals that reverted to the FHH genotype in the 99.4-Mb Rf-2 region but remained heterozygous for the BN genotype in the 2.4-Mbp region of interest from 258.8 to 261.2 Mbp of RNO1. Pairs of these animals were intercrossed to generate the FHH.1BN strain F.

Genotyping.

Genomic DNA was isolated from a piece of tail or the ear using a Direct PCR lysis reagent (Viagen 102-T) and then subjected to PCR amplification using 5′-fluorescent-labeled primers. The PCR reactions were performed in a 10-μl volume and contained 1 μl 10× buffer, 100 nM forward and reverse primers, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 250 μM dNTPs, 25 nM Taq polymerase, and 20 ng of genomic DNA. The reactions were denatured at 94° C for 3 min and cycled 25 times at 94° C for 1 min, 55° C for 2 min, and 72° C for 3 min. The products were mixed with loading dye (1:1), denatured, loaded on sequencing gels, and read using an ABI 3700 sequencer.

Protocol 2: Autoregulation of RBF in FHH and FHH.1BN Congenic Strains

These experiments were performed in 12-wk-old FHH rats and rats from FHH.1BN congenic strains A, C, D, E, and F (n = 45). The rats were anesthetized with ketamine (30 mg/kg; Phoenix Pharmaceutical, St. Joseph, MO) and Inactin (50 mg/kg; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and a PE-240 cannula was placed in the trachea to facilitate breathing. The femoral artery and vein were cannulated for intravenous (iv) infusions and measurement of arterial pressure, and a clamp was placed on the aorta above the left renal artery for control of renal perfusion pressure (RPP). A 2-mm ultrasonic Doppler flow probe (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY) was placed on the left renal artery to measure RBF. The rats received an iv infusion of 0.9% NaCl solution containing 2% BSA at a rate of 100 μl/min to replace surgical fluid losses. After surgery and a 30-min equilibration period, the rats were acutely volume expanded with a solution of 6% BSA in 0.9% NaCl at a dose of 1 ml/100 g to inhibit tubuloglomerular feedback responsiveness. The celiac and mesenteric arteries were then tied off to raise mean arterial pressure (MAP) to ∼150 mmHg, and RBF was measured as RPP was lowered from 140 to 60 mmHg in 10-mmHg increments by adjusting the clamp on the aorta.

Protocol 3: Time Course of Development of Hypertension, Proteinuria, and Glomerular Injury in FHH and FHH.1BN Congenic Strains

These experiments were performed in 9- to 21-wk-old FHH, FHH.1BN control congenic strain A that did not autoregulate RBF and FHH.1BN congenic strains C, E, and F that did autoregulate RBF. Proteinuria was measured at 9, 12, 15, 18, and 21 wk using the Bradford method and BSA as the standard (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). At each time point, the rats were placed in metabolic cages overnight for determination of protein excretion. At 11 wk of age, some of the rats in each group were anesthetized with isoflurane and telemetry catheters (model TA11PAC40, Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) were surgically implanted in the femoral artery with transmitters placed under the skin. MAP was recorded between 9 and 12 AM when the rats were 12, 15, 18, and 21 wk of age. At 21 wk, the rats were anesthetized and the kidneys were flushed with 10 ml of 0.9% NaCl via a cannula placed in the aorta. The kidneys were then collected, weighed, and fixed in a 10% buffered formalin solution. Paraffin sections were cut (3 μm) and stained with Masson's trichrome to determine the degree of glomerular injury and renal interstitial fibrosis. Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse 55i microscope with a Nikon DS-Fi1 color camera (Nikon, Melville, NY) and NIS-Elements D 3.0 software. The degree of glomerular damage was assessed on 30–40 glomeruli/section as the percentage of the glomerular capillary area filled with matrix material on a 0–4 scale, with 0 representing no injury, 2 indicating loss of 50% of glomerular capillary area, and 4 representing the complete obstruction of glomerular capillaries. Interstitial fibrosis was analyzed using NIS-Elements automated measurements software after thresholding for determination of the percentage of the image stained blue.

Protocol 4: Myogenic Response in Isolated Afferent Arterioles

The myogenic response was measured in afferent arterioles microdissected from the kidneys of 8- to 10-wk-old FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strains E and F. The rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, and the kidneys were removed and placed in ice-cold MEM (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) containing 5% BSA. Superficial afferent arterioles with an attached glomerulus were microdissected, transferred to a temperature-regulated chamber (37°C) mounted on an inverted microscope (Eclipse Ti; Nikon, Melville, NY), and cannulated with glass pipettes. Afferent arterioles were perfused with MEM from the proximal end. The vessels were imaged using a digital CCD camera (CoolSnap Photometrics, Tucson, AZ), and the images were displayed and vessel diameters were determined using NIS-Elements imaging software (Nikon). Perfusion pressure was set to 60 mmHg, and after a 30-min equilibration period the baseline diameter of the vessel was determined. Perfusion pressure was then increased to 120 mmHg, and after 5 min the diameter of the vessel was redetermined. Additional experiments were performed in afferent arterioles isolated from FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strain F before and after removal of Ca2+ from the bath to determine the degree of myogenic tone. Experiments were also performed in vessels isolated from FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strains E and F before and after treatment with iberiotoxin (100 nM; Anaspec, Fremont, CA) to determine the influence of the large-conductance K+ channel on the myogenic response.

Protocol 5: Patch-Clamp Experiments

These experiments were performed in VSMCs freshly isolated from renal interlobular arteries microdissected from the kidneys of FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strains E and F. These vessels were used as it is difficult to microdissect a sufficient number of afferent arterioles in a limited period of time to isolate VSMCs, and we have previously reported that the myogenic response is impaired in isolated interlobular arteries of FHH rats (43), thereby validating use of interlobular renal vessels as a source to isolate renal VSMCs for patch-clamp experiments. The rats were anesthetized using isoflurane. The kidneys were removed, placed in ice-cold PBS, and renal interlobular arteries were microdissected. After dissection, the arteries were digested in a dissociation solution containing 145 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 0.05 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM glucose for 10 min at room temperature. The undigested vessels were pelleted at 1,000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was removed. The vessels were incubated in fresh dissociation solution also containing papain (22.5 U/ml, Sigma) and dithiothreitol, 1 mg/ml, for 12 min at 37°C and centrifuged at 1,000 RPM for 5 min. The supernatant was removed, and then the vessels were incubated in fresh dissociation solution containing collagenase (250 U/ml; Sigma), trypsin inhibitor (10,000 U/ml), and elastase (2.4 U/ml) and incubated for 12 min at 37°C. Single cells were released by gentle pipetting of the digested tissue. The supernatant containing VSMCs was collected, and the VSMCs were pelleted by centrifugation. They were then resuspended in fresh dissociation solution and held at 4°C until use in a patch-clamp experiment that was performed within 2–4 h after cell isolation.

Whole cell patch-clamp experiments.

K+ currents were recorded from VSMCs using a whole cell patch-clamp mode at room temperature. The bath solution contained (in mM) 130 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4), and the pipettes were filled with a solution containing (in mM) 130 K gluconate, 30 KCl, 10 NaCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). The concentrations of EGTA and Ca2+ in the pipette solution were varied to obtain cytosolic free Ca2+ concentrations of 0.1 or 1 μM. The patch-clamp pipettes were constructed from 1.5-mm borosilicate glass capillaries using a two-stage micropipette puller (model PC-87; Sutter Instruments, San Rafael, CA) and heat-polished using a microforge. The pipettes had tip resistances of 2–8 MΩ. The tip of a pipette was positioned on a cell, a 5- to 20-GΩ seal was formed, and the membrane was ruptured by repeated gentle suction with a glass syringe. An Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) was used to clamp pipette potential and record whole cell currents. The amplifier output signals were filtered at 2 kHz using an eight-pole Bessel filter (Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MA). The currents were digitized at a rate of 10 kHz and stored on the hard disk of a computer for off-line analysis. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using Clampfit software (version 10.0, Axon Instruments). Outward currents were elicited by 20-mV voltage steps (300-ms duration, 5-s intervals) from −60 to +120 mV from a holding potential of −40 mV. Peak current amplitudes were obtained by averaging 5–10 trials. Membrane capacitance was determined by integrating the average capacitance in response to a 5-mV pulse. Peak currents were expressed as current density (pA/pF) to normalize for differences in the size of the VSMCs. In some experiments, the pipette tips were loaded with a control pipette solution and then back-filled with solution containing 300 nmol/l iberiotoxin (Anaspec) so that the BKCa current could be measured before and after blockade of the large-conductance BKCa channel.

Single-channel experiments.

Single-channel BKCa currents were recorded from VSMCs using inside-out patch-clamp mode at room temperature. The bath solution contained (in mM) 145 KCl, 0.37 CaCl2, 1.1 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). The pipettes were filled with a solution containing (in mM) 145 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.1 MgCl2, and 5 HEPES (pH 7.4). Free cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations were adjusted to 0.1 or 1 μM. The pipettes had a tip resistance of 8–10 MΩ. After positioning of the pipette top on the surface of a cell, a GΩ seal (5–20 GΩ) was formed by applying light suction. The inside-out patch configuration was achieved by rupturing the membrane with a sudden upward movement of the pipette. An Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments) was used to clamp pipette potential and record single-channel currents. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using pCLAMP software (version 7.02, Axon Instruments). Open-state probability (NPo) for single-channel currents, expressed as a percentage of the total recording time in which a channel was open, was calculated using the equation NPo = (ΣTj × j)/T; where Tj is the sum of the open time at a given conductance level, j represents multiples of a given conductance, and T is the total recording time. Single-channel current recordings at membrane potentials between −60 and +80 mV and at [Ca2+]i of 0.1 or 1 μM were used to calculate NPo.

Protocol 6: Sequencing and Expression Analysis of Genes in the 2.4-Mb Candidate Region

Sequencing of FHH/EurMcwi genomic DNA was performed using an Illumina HiSeq 2000. Sequence reads were aligned to the BN reference genome and single nucleotide variants (SNVs) were called using the CASAVA v1.8.1 program (Illumina, San Diego, CA). The potential functional consequences of variants identified by 10 or more reads with a variant frequency of >40% were predicted with Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor v2.21. Predicted nonsynonymous variants were further analyzed using the Polyphen program (31) to predict the functional consequence to the protein. To confirm that the predicted sequence variants were also captured in the FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strains in our colonies, two of the functionally interesting positional candidate genes in the region (Dusp5 and Add3) were resequenced by Sanger sequencing as described before (35). PCR primers were designed to amplify all the exons and introns across the coding regions of these genes from genomic DNA. The primers included M13 tails that allow for direct sequencing of the products using a big dye terminator cycle sequencing kit and an ABI model 3730 automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The sequence files were transferred to a UNIX workstation, and base calling sequence assembly and polymorphism detection were performed using a variety of sequence analysis programs, i.e., PHRED, PHRAP, CONSED, and POLYPHRED, looking for stop codons, splice variants, altered start sites, frame shifts, and/or major amino acid substitutions that could alter the function of these proteins.

Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) assays were also performed to determine whether any of the genes in this region are differentially expressed in renal microvessels. Renal microvessels were bulk-isolated from the kidneys of 10-wk-old FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strain F (6 rats/group) using a previously described sieving method (6, 49). The rats were anesthetized with isoflurane. A midline abdominal incision was made, and the abdominal aorta was cannulated. The kidneys were flushed with 5 ml of an ice-cold physiological salt solution followed by 5 ml of a 1% solution of Evans blue to aid in visualizing vessels. The kidneys were removed, and the renal cortex was isolated and pushed through a 150-μm sieve that was autoclaved and treated with RNAlater. Glomeruli and tubules passed through the sieve, leaving intact vascular trees on the screen for collection. We have previously reported that this method for isolation of renal microvessels is very effective at removing glomeruli and tubules, and the vascular preparation is >95% pure with some contamination by adherent proximal tubules. The resulting microvessel preparation was collected in RNAlater and examined under a stereomicroscope for any remaining tubular tissue, which was removed by microdissection before placing of the vessels in TRIzol to isolate the RNA. We previously reported that the residual contamination of bulk isolated microvessels by tubules after microdissection as assessed by measuring expression of the proximal tubular markers, γ-glutamyl transferase, and alkaline phosphatase is negligible (49).

After isolation, the vessels were homogenized using a ground-glass tissue homogenizer in 250 μl TRIzol (Invitrogen), and RNA was isolated. The RNA concentration of the samples was determined using a Synergy 2 plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT), and the concentration was adjusted to 1,000 ng/μl. RNA quality was evaluated using the Experion system (Bio-Rad). RNA was converted to cDNA using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) using 1 μg of input RNA in a 20-μl reverse transcription reaction. Q-PCR reactions were performed using a CFX96 Real-Time System C1000 Thermal Cycle (Bio-Rad) and normalized to the expression of β-actin. The primers used to amplify the various genes in the region are presented in Table 1. Q-PCR contained Fast SYBR Green Master mix (Thermo Scientific), 0.25 ng of the forward/reverse primers, and 4 ng of cDNA in a total of 25 μl. The thermal profile consisted of 95°C for 10 min, then 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 58°C for 30 s, 72°C for 25 s, and a final melt curve was generated from 65 to 95°C in 0.5°C increments. Reactions without template cDNA were performed to assess nonspecific signals. Each sample was assayed in triplicate.

Table 1.

Forward and reverse primers used in quantitative PCR experiments to compare the expression of genes in renal vessels of the 2.4-Mbp region of interest in FHH/EurMcwi2 vs. BN rats

| Genes in the 2.4-Mbp Region | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| RGD1561333 Similar to 60S ribosomal L8 | gtgggcaccatgcctgaggg | tcaattctgcccccgccagc |

| Soluble X-prolylaminopeptidase 1 | actacgcgccgatccctgaga | gccgtgtcctgttccgtgca |

| MAX interactor 1 | cgtctgtggcgcctcctgtc | gcgcaggtgagctcgtcgatt |

| Adducin 3 (gamma) | gcagccaagcggtgatcac | gccatgatgtagtcggcgatctgc |

| LOC100360467 Max interator 1-like | cgcagggagcgagagtgtga | ctgtgcccggctcaacctcc |

| LOC100360898 Max interator 1-like | aagtggaggccttcgtgccg | gcgcaggtgagctcgtctcaa |

| Survival motor neuron domain | cgaccgaatctcgtcgtggtgg | tcctctgacatcttgggtgggact |

| LOC100360511 Hypothetical protein | agccccgcaccctcacagag | ggcctagtcgggcctcaggg |

| Dual-specificity phosphatase 5 | cgtgctggaccagggcagccg | gag aatgggctttccgcactg |

| LOC100360558 Ribosomal S12-like | ggccgaggaaggcatagctgc | gccatcgtggatgagggcgg |

| Structural maintenance of chromosome 3 | cgcgctgttgcggttctgag | cgaggacctgtaccctcgtgc |

| RNA binding motif protein 20 | ggcccccgagggtaccaagt | gtcccagcctcattctctgccc |

| Programmed cell death 4 | gcccgtgttggcagtgtcct | gcccaccaactgtggtgctct |

| LOC100360174 Binding domain 3-like | gagaagggggagacactgtgcca | tcccccagtctgcgccgtaa |

| Soc-2 (suppressor of clear) homolog | ccctgccgagatcggtgaact | agctcctcaagtgcgctgcat |

| β-Actin | ctatgttgccctagacttcgagc | gatagagccaccaatccacacag |

BN, Brown Norway rats.

Statistical Analysis

Mean values ± SE are presented. The significance of the difference in mean values was determined using SigmaStat software and a paired t-test (2 samples) or a one-way or two-way analysis of variance for repeated measures followed by a Holm-Sidak test for preplanned comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Protocol 1: Generation of Subcongenic Strains from FHH.1BN Congenic Strain C

A genetic map comparing the regions of BN RNO1 introgressed into the various FHH.1BN congenic strains are presented in Fig. 1. We previously reported that transfer of a 99.4-Mb region of rat RNO1 from BN rats from marker D1rat183 to D1rat76 encompassing the Rf-2 locus along with a 12.9-Mb region on the q terminus of the chromosome in the RF1 region (strain B, Fig. 1) restored autoregulation of RBF and reduced proteinuria in FHH.1BN double congenic strain B (24). Subsequently, we developed an additional double congenic strain C and narrowed the region of interest to a 4.7-Mb region on RNO1 (48). In the present study, we created two additional double congenic strains, D and E, that split the 4.7-Mb introgressed BN region on the q terminus of RNO1 in half. Finally, we took strain E in which autoregulation of RBF was restored and backcrossed them with FHH rats and intercrossed the progeny to create a minimal FHH.1BN congenic strain F in which the 99.4-Mb region of BN RNO1 in the Rf-2 region in congenic strains A through E was reverted back to FHH alleles. Overall, a 2.4-Mb region of the BN rat in RNO1, spanning markers D1Rat09 to D1Rat225, was introgressed in FHH.1BN congenic strain F. According to RGD, there are 15 known and predicted genes in this region listed in Fig. 1. Of these, only three genes, i.e., adducin-γ (Add3), dual-specificity phosphatase 5 (Dusp5), and X-prolyl aminopeptidase 1 (Xpnpep1), have any reported influence on cardiovascular function.

Protocol 2: Autoregulation of RBF in FHH and FHH.1BN Congenic Strains

The results of these experiments are presented in Fig. 2. Basal blood pressures measured under Inactin anesthesia were not significantly different between the strains and averaged ∼120 mmHg. Baseline RBF measured at this basal blood pressure was also not significantly different between FHH rats and strains A, C, D, E, and F and averaged 7.8 ± 0.8, 9.0 ± 1.1, 9.9 ± 0.7, 6.5 ± 1.4, 9.9 ± 0.6, and 8.8 ± 0.7 ml·min−1·g kidney wt−1, respectively. Control values of RBF measured at a renal perfusion pressure of 100 mmHg were not significantly different between FHH rats and the congenic strains and averaged 6.7 ± 0.6, 8.2 ± 1.0, 9.8 ± 0.5, 5.8 ± 1.4, 9.8 ± 0.6 and 8.6 ± 0.6 ml·min−1·g kidney wt−1 in FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strains A, C, D, E, and F, respectively.

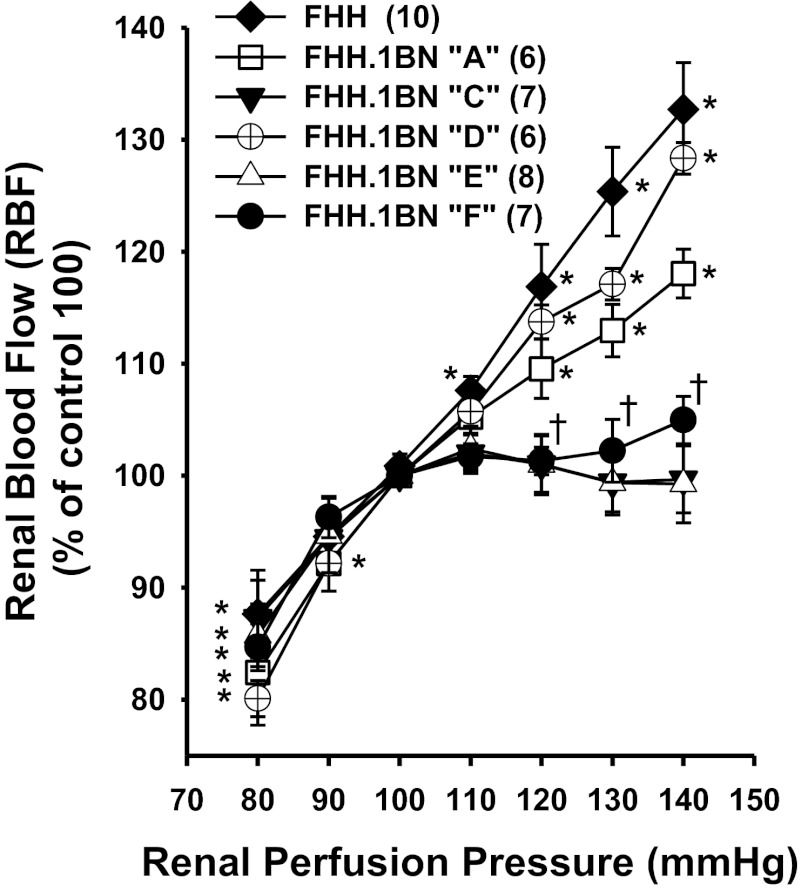

Fig. 2.

Relationship between renal perfusion pressure (RPP) and renal blood flow (RBF) in volume-expanded FHH rats and the FHH.1BN congenic strains. Values are means ± SE. The numbers in parentheses indicate number of animals studied per strain. Control values of RBF measured at a renal perfusion pressure of 100 mmHg were not significantly different between FHH rats and the FHH.1BN congenic strains A, C, D, E, and F and averaged 6.7 ± 0.6, 8.2 ± 1.0, 9.8 ± 0.5, 5.8 ± 1.4, 9.8 ± 0.6 and 8.6 ± 0.6 ml·min−1·g kidney wt−1, respectively. *Significant difference from the control value at 100 mmHg within a strain (P < 0.05). †Significant difference in strains C, E, and F from the corresponding value change in FHH rats (P < 0.05).

Autoregulation of RBF was poor in FHH rats and increased 33% as renal perfusion pressure was increased from 100 to 140 mmHg. Similar results were obtained in rats of FHH.1BN congenic strain D, in which a 2.3-Mb region of BN RNO1 from markers D1Rat376 to D1Rat09 was introgressed onto the FHH background. Autoregulation of RBF was also poor in the FHH.1BN congenic strain A. In contrast, RBF was well autoregulated in FHH.1BN congenic strains C, E, and F, indicating the region of interest that restores autoregulation lies within the 2.4-Mb region of BN RNO1 between markers D1Rat09 and D1Rat225.

Protocol 3: Time Course of Development of Hypertension, Proteinuria, and Glomerular Injury in FHH and FHH.1BN Congenic Strains

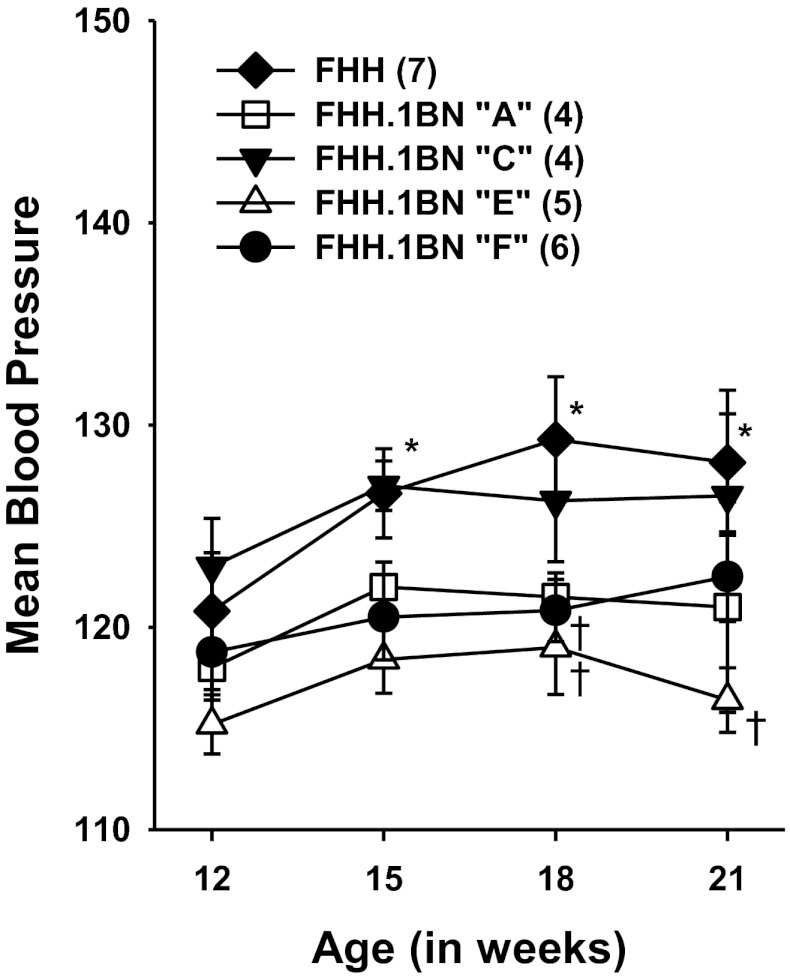

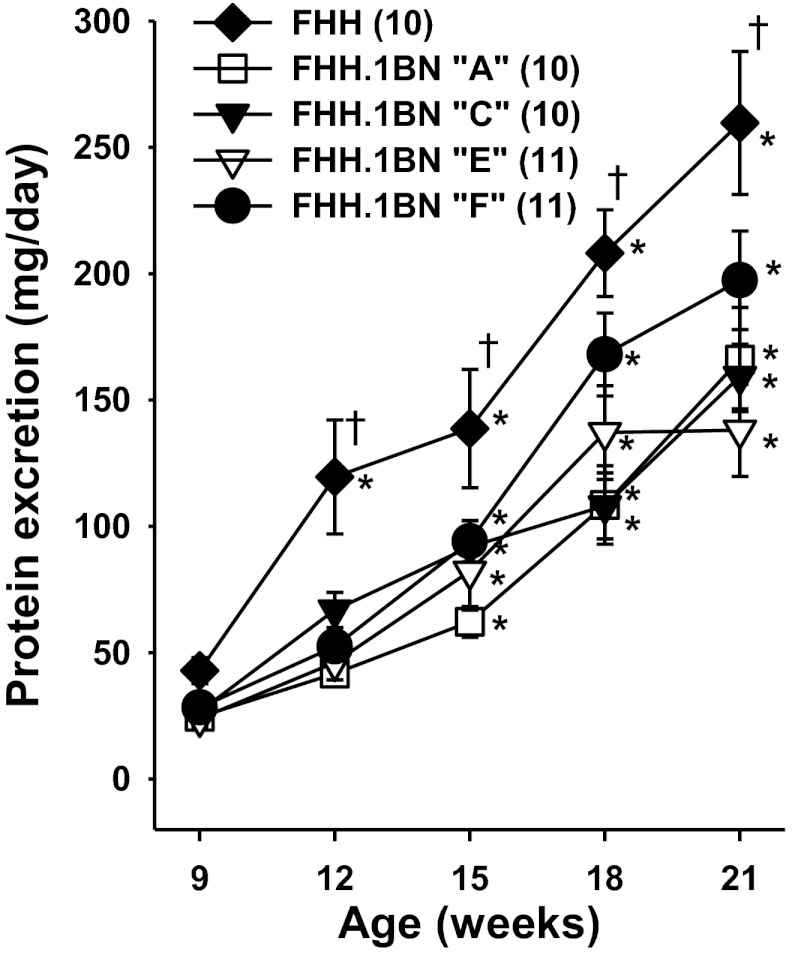

A comparison of the time course of changes in blood pressure and proteinuria are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. There was a small (10 mmHg) but significant increase in MAP in FHH rats over the course of the study, but not in congenic strains A, C, E, and F (Fig. 3). Protein excretion, (Fig. 4) rose from 42 ± 5 to 259 ± 28 mg/day in FHH rats as they aged from 9 to 21 wk of age. Protein excretion rose to a lesser extent in FHH.1BN congenic strain A that did not autoregulate RBF but has BN in the 99.4-Mbp region of RNO1 which replaces the defective FHH Rab38 gene in the Rf-2 QTL which has been previously reported to contribute to the development of proteinuria in FHH rats by impairing the reuptake of filtered protein (32). A reduction in proteinuria was also seen in congenic strains C and E that did autoregulate RBF but also share the same BN genotype in the Rf-2 region as strain A. Finally, protein excretion was significantly reduced in the minimal FHH.1BN congenic strain F that autoregulates RBF, but does not share the BN genotype in the Rf-2 region.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the time course of changes in mean arterial pressure in FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strains. Values are means ± SE. Numbers in parentheses indicate number of animals studied per strain. *Significant difference from the control value at 12 wk of age within a strain (P < 0.05). †Significant difference from the corresponding value in FHH rats (P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the time course of changes in proteinuria in FHH rats and the FHH.1BN congenic strains. Values are means ± SE. Numbers in parentheses indicate number of animals studied per strain. *Significant difference from the control value at 12 wk of age within a strain (P < 0.05). †Significant difference from the corresponding value in FHH rats (P < 0.05).

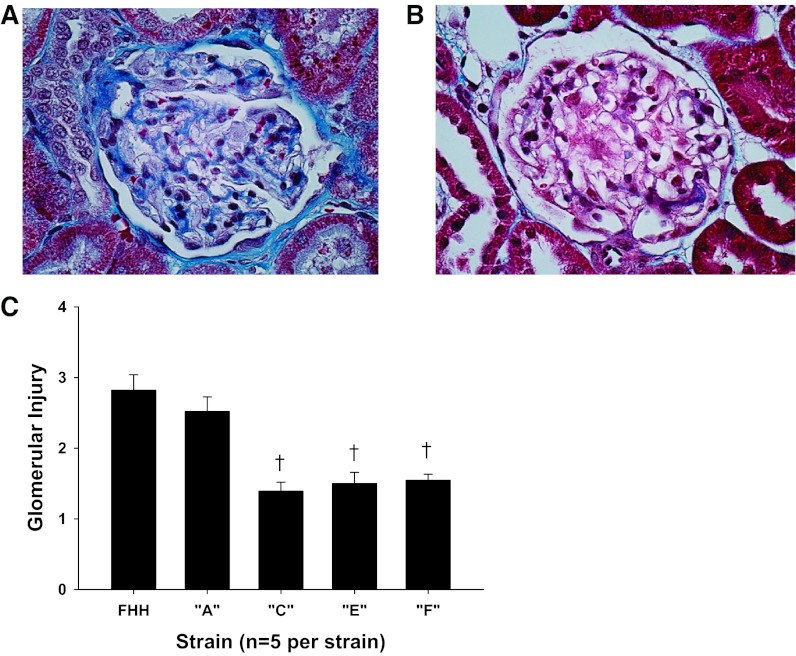

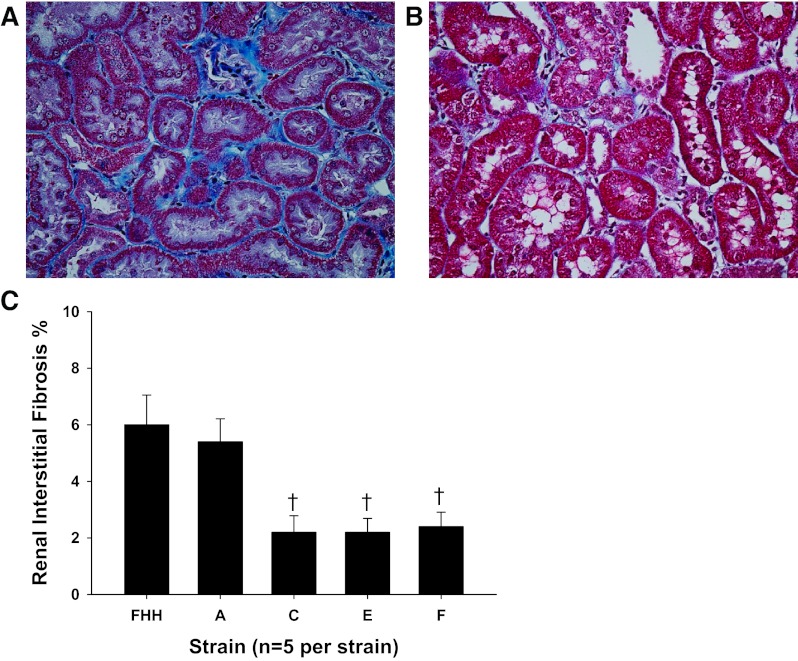

A comparison of the degree of glomerular injury and renal interstitial fibrosis in FHH and the FHH.1BN congenic strains are presented in Figs. 5 and 6. Representative images of a glomerulus from FHH rats (Fig. 5A) and FHH.1BN congenic strain F (Fig. 5B) are presented. The FHH rats exhibit severe glomerulosclerosis with expansion of the mesangial matrix and increased collagen deposition. The glomerular injury score averaged nearly 3 in 21-wk-old FHH rats, indicating that 75% of the capillary filtration area was lost from most of the glomeruli in the kidney. The degree of glomerular injury was significantly reduced in congenic strains C, E, and F (Fig. 5C) relative to the levels seen in FHH rats and congenic strain A, which does not autoregulate RBF.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of glomerular injury in FHH rats and the FHH.1BN congenic strains. A and B: representative examples of the degree of glomerular injury seen in 21-wk-old FHH rats (A) and FHH.1BN congenic strain F (B). C: glomerular injury scores measured in all the strains. Values are means ± SE measured from 150 glomeruli (30 glomeruli/rat from 5 rats/strain). *Significant difference from the corresponding value in FHH rats (P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the degree of renal interstitial fibrosis in FHH rats and the FHH.1BN congenic strains. Shown is representative appearance of the renal cortex of 21-wk-old FHH rats (A) and the FHH.1BN congenic strain F (B). Slides were stained with Masson's trichrome, and the blue color indicates regions of collagen deposition and fibrotic injury. C: renal interstitial fibrosis scores of all strains. Values are means ± SE. Fifteen regions were scored/kidney, and 5 rats/strain were studied. *Significant difference from the corresponding value in FHH rats (P < 0.05).

Representative images presenting the degree of renal interstitial fibrosis in FHH rats and the minimal FHH.1BN congenic strain F are presented in Fig. 6, A and B, respectively. FHH rats exhibited severe interstitial fibrosis and tubular necrosis, whereas very little fibrosis was found in the renal cortex of FHH.1BN congenic strain F that autoregulates RBF. A comparison of the degree of renal interstitial fibrosis in all of the congenic strains is presented in Fig. 6C. The degree of renal interstitial fibrosis was significantly reduced in the FHH.1BN congenic strains C, E, and F that autoregulate RBF relative to the levels seen in FHH rats but not in FHH.1BN congenic strain A, which did not autoregulate RBF.

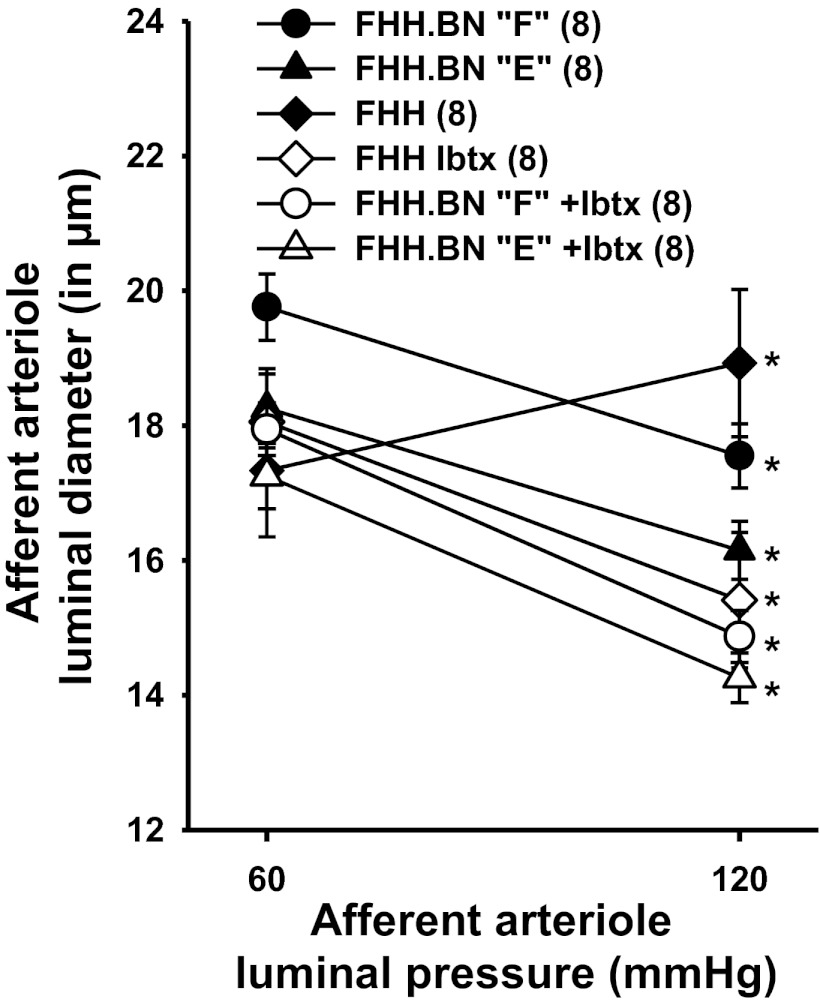

Protocol 4: Myogenic Response in Isolated Afferent Arterioles

A comparison of the myogenic response of isolated perfused afferent arterioles of FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strains E and F is presented in Fig. 7. The myogenic response of the afferent arterioles of FHH rats was impaired, and the diameter of these vessels increased significantly when transmural pressure was increased from 60 to 120 mmHg. In contrast, the diameter of afferent arterioles microdissected from the kidneys of FHH.1BN congenic strains E and F decreased significantly when transmural pressure was elevated. Blockade of BKCa channels with iberiotoxin (100 nM) restored the myogenic response of the afferent arterioles isolated from FHH rats, but it had no effect on vessels isolated from congenic strains E and F.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of the myogenic response of afferent arterioles obtained from FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strains E and F before and after addition of 100 nM iberiotoxin (Ibtx) to the bath. Values are means ± SE. Numbers in parentheses indicate number of animals studied per strain. *Significant difference from the corresponding value at 60 mmHg within a strain (P < 0.05).

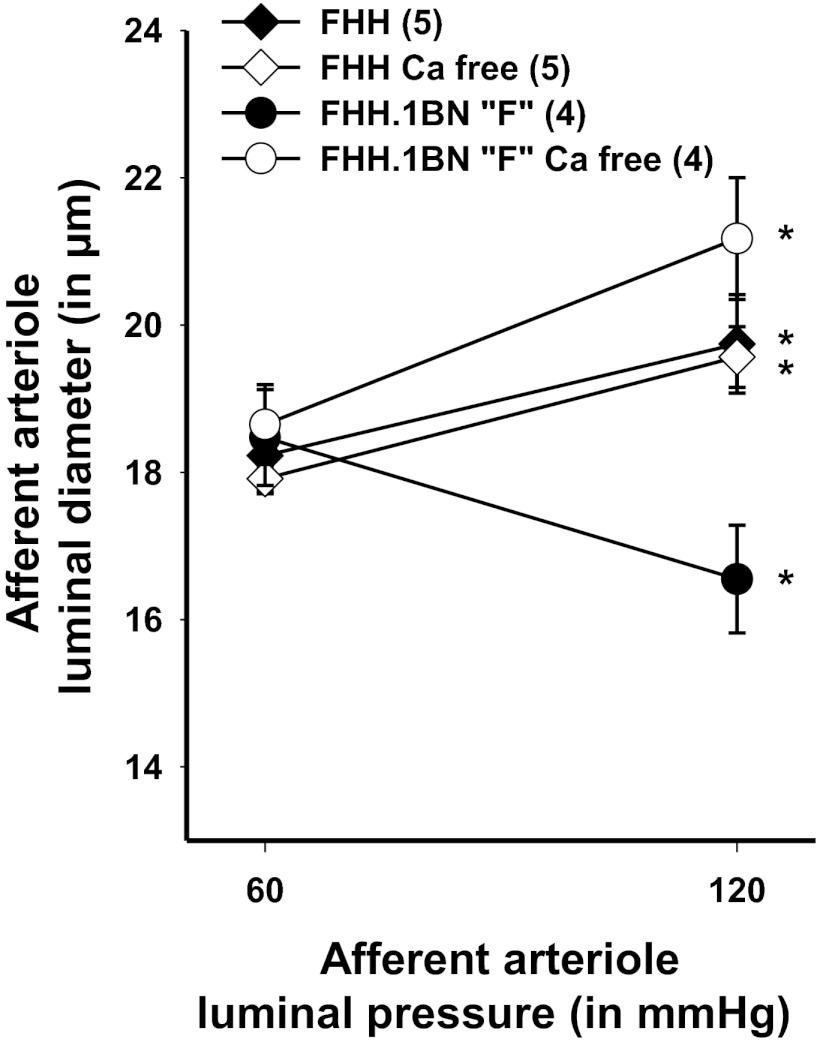

The results of experiments to determine the degree of myogenic tone in FHH rats vs. the FHH.1BN congenic strain F are presented in Fig. 8. Afferent arterioles from FHH.1BN congenic strain F constricted in response to an increase in transmural pressure, but the vessel dilated in response to the same stimulus after removal of calcium from the bath, indicating development of substantial myogenic tone. In contrast, the afferent arterioles of FHH rats failed to constrict in response to an increase in transmural pressure, and removal of calcium from the bath had no effect on the response, indicating these vessels fail to develop any myogenic tone.

Fig. 8.

Comparison of the myogenic response of afferent arterioles obtained from FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strain F with before and after removal of calcium (Ca2+) from the bath. Values are means ± SE. Numbers in parentheses indicate number of animals studied per strain. *Significant difference from the corresponding value at 60 mmHg within a strain (P < 0.05).

Protocol 5: Patch-Clamp Experiments

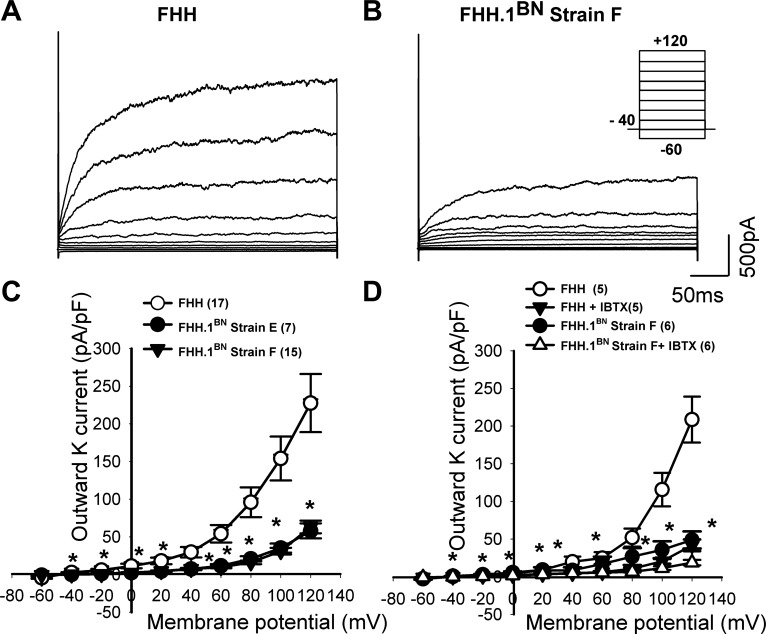

Whole cell studies.

A representative tracing of whole cell K+ channel currents recorded from VSMCs isolated from renal arterioles of FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strain F are presented in Fig. 9, A and B. Membrane K+ currents were elicited by a series of 20-mV depolarizing steps (−60 to +120 mV) from a holding potential of −40 mV (Fig. 9B, inset protocol). Cell capacitance was not significantly different among three groups and averaged 16.7 ± 1.5, 15.3 ± 0.83, and 16.5 ± 1 pF in VSMCs isolated from FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strains E and F, respectively. K+ channel current was significantly increased at depolarized potentials in renal VSMCs isolated from FHH rats (+40 mV; 19.4 ± 5 pA/pF) by 2.9- and 3.6-fold relative to the currents recorded from VSMCs isolated from FHH.1BN congenic strains E and F (Fig. 9C), respectively. Administration of iberiotoxin (300 nM), a selective BKCa channel blocker, reduced K+ current to a greater extent in VSMCs isolated from FHH rats than that seen in the congenic strain F (Fig. 9D), indicating that increased activity of BKCa channels is primarily responsible for the increased K+ current in VSMCs isolated from FHH rats (FHH rats: +40 mV; before iberiotoxin 19.2 ± 6.2 pA/pF, after iberiotoxin 4.9 ± 1.9 pA/pF; FHH.1BN strain F; +40 mV; before iberiotoxin 4.5 ± 0.6 pA/pF and after iberiotoxin 4.2 ± 01 pA/pF).

Fig. 9.

Comparison of whole cell K+ channel currents recorded from vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) isolated from renal interlobular arteries obtained from FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strains E and F. Shown are representative outward K+ membrane current traces elicited in FHH rats (A) and FHH.1BN strain F (B) by a series of 20-mV depolarizing steps (−60 to +120 mV) from a holding potential of −40 mV (inset protocol in B) at 1 μM free cytosolic calcium (Ca2+)i.. C: summary of the current-voltage curves of total outward K+ channel currents in VSMCs isolated from FHH and FHH.1BN strains E and F. D: summary of current-voltage curves of outward K+ channel currents in the presence and absence of iberiotoxin (IBTX) to selectively block BKCa channels in VSMCs isolated from FHH and FHH.1BN strain F. Values are means ± SE. *Significant difference from the corresponding value in FHH rats (P < 0.05).

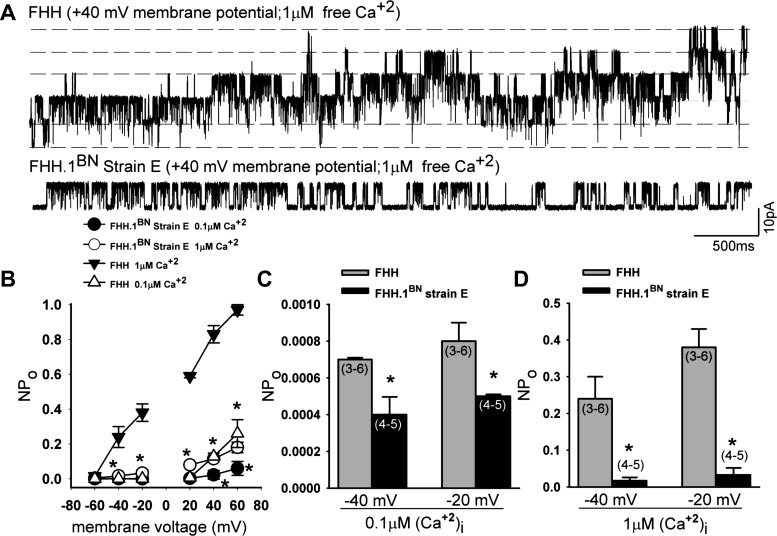

Single-channel studies.

Figure 10A presents representative BKCa single-channel currents recorded from FHH rats and FHH.1BN strain E rats at +40 mV membrane potential and 1 μM free calcium in the bath solution. Single-channel current amplitude plotted as a function of membrane potential is not altered in either strain at 0.1 and 1 μM Ca2+ (data not shown). BKCa channels exhibited an enhanced NPo in response to membrane depolarization or increasing intracellular Ca2+ levels in both FHH and FHH.1BN strain E (Fig. 10B). The NPo of the BKCa channel was markedly elevated at all membrane potentials in FHH rats relative to the congenic strain E when channel activity was recorded at a maximal intracellular Ca2+ concentration of 1,000 nM. This difference was even apparent at physiological membrane potentials of −40 mV (Fig. 10D). NPo was also significantly greater in VSMCs isolated from FHH rats than in FHH.1BN rats as recorded at physiological membrane potentials of −40 mV in the presence of normal resting intracellular Ca2+ concentrations of 100 nM (Fig. 10C).

Fig. 10.

Comparison of BKCa single-channel currents recorded from inside-out patch clamp of VSMCs isolated from FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strain E. A: representative BKCa single-channel currents recorded from FHH and FHH.1BN congenic strain E rats at +40-mV membrane potential and 1 μM free calcium in the bath solution. Single-channel current amplitude plotted as a function of membrane potential is not altered in either strain at 0.1 and 1 μM (Ca2+)i (data not shown). B: open-state probability (NPo) plotted as a function of membrane voltage (mV) is higher in FHH rats compared with the values obtained in FHH.1BN congenic strain E rats at 0.1 and 1 μM (Ca2+)i; FHH: n = 3–6 patches/data point at 0.1 and 1 μM free calcium; FHH.1BN: n = 4–5 patches/data point at 0.1 and 1 μM free calcium. C and D: summary graphs of NPo at −40- and −20-mV membrane potential in FHH and FHH.1BN strain E rats at 0.1 and 1 μM Ca2+. Values are means ± SE. *Significant difference from the corresponding value in FHH rats (P < 0.05).

Protocol 6: Sequencing and Expression Analysis of Genes in the 2.4-Mb Candidate Region

Examination of the Rat Genome Database (39) and other sites indicated that there are currently 15 known and predicted genes that map to the 2.4-Mbp region of interest on rat RNO1 (Fig. 1). The results of our comparative sequence analysis identified 3,469 SNVs in FHH/EurMcwi rats vs. the reference BN sequence with a sequence depth of 10 reads or greater and a frequency of 40% or greater. Of the 3,469 variants identified, 791 are located in 11 of 15 genes of the 2.4-Mbp region of interest, and 20 of these SNVs were found in coding regions of these genes (Table 2). Four genes had no sequence coverage, RGD1561333, Mxi1, LOC100360467, and LOC100360898. The nonsynonymous variants (nsSNVs) found in the coding regions of the Add3 and Soc-2 homolog (Shoc2) genes are predicted to be possibly damaging by Polyphen, while nsSNVs in RNA binding motif protein 20 (Rbm20) are predicted to be benign. Of these, two nsSNVs located in Add3 result in a substitution of threonine to serine in exon 2 and lysine to glutamine in exon 13. More than 700 SNVs were identified in the introns of three genes (Xpnpep1, Add3, and Rbm20), suggesting a high degree of genetic diversity between FHH and BN rats in these genes, but the functional significance of these sequence variants in the intronic regions remain to be further investigated.

Table 2.

Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) of genes in the 2.4-Mbp region of interest in FHH/EurMcwi2 vs. BN rat

| Symbol | Gene | No. of SNVs | No of SNVs in Exons | No. of Changes in Amino Acid | Polyphen Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGD1561333 | RGD1561333 Similar to 60S ribosomal L8 | N/A | |||

| Xpnpep1 | Soluble X-prolylaminopeptidase 1 | 187 | 3 | 0 | |

| Mxi1 | MAX interactor 1 | N/A | |||

| Add3 | Adducin 3 (gamma) | 231 | 7 | 2 | Possibly damaging |

| LOC100360467 | LOC100360467 Max interactor 1-like | N/A | |||

| LOC100360898 | LOC100360898 Max interactor 1-like | N/A | |||

| Smndc1 | Survival motor neuron domain | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| LOC100360511 | Hypothetical protein | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Dusp5 | Dual-specificity phosphatase 5 | 14 | 2 | 0 | |

| LOC100360558 | LOC100360558 Ribosomal protein S12-like | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Smc3 | Structural maintenance of chromosome 3 | 19 | 3 | 0 | |

| Rbm20 | RNA binding motif protein 20 | 327 | 4 | 2 | Benign |

| Pdcd4 | Programmed cell death 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| LOC100360174 | LOC100360174 Binding domain 3-like | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Shoc2 | Soc-2 (suppressor of clear) homolog | 7 | 1 | 1 | Possibly damaging |

N/A, sequence not available.

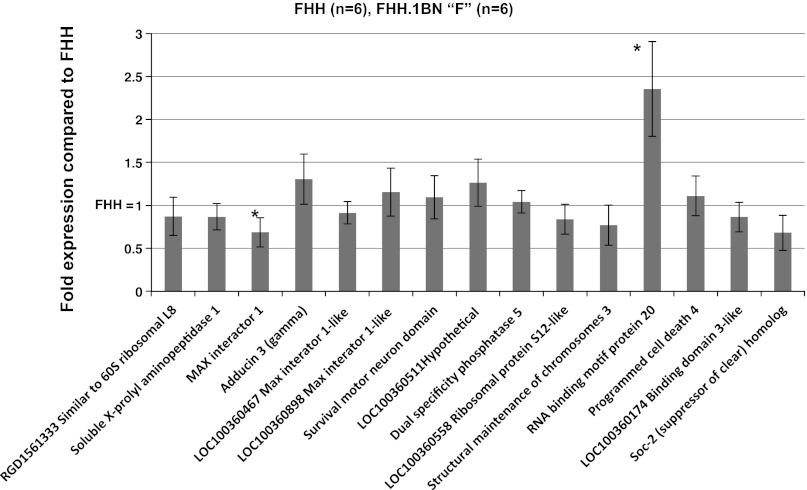

Because of the large number of sequence variants identified in introns and the noncoding regions of many of the genes in the region, we also compared the expression of all 15 genes in renal microvessels isolated from 10-wk-old FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strain F (Fig. 11). Only the “Max interactor 1” (Mxi1) and Rbm20 genes were differentially expressed. However, the expression levels of both of these genes are extremely low, with only 0.27 copies of the Mxi1 gene expressed per 1,000 copies of β-actin in strain “F” vs. 0.39 per 1,000 copies of β-actin in FHH. Similarly, 2.52 copies of the Rbm20 gene were expressed per 1,000 copies of β-actin in strain “F” vs. 1.07 copies per 1,000 copies of β-actin in FHH rats.

Fig. 11.

Comparison of the expression of the 15 genes in the 2.4-Mb region of interest in renal microvessels isolated from FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strain F. Data are expressed as the ratio of CT of the target gene/CT of B actin and were normalized to the expression level seen in FHH rats. Values are means ± SE from vessels isolated from 6 rats/strain. *Significant difference from the corresponding value in FHH rats (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The FHH rat is a genetic model that develops mild hypertension, proteinuria and glomerular disease (21, 30, 37, 47) (22, 25–26, 41–42). We have previously reported that the development of proteinuria and glomerular injury in FHH rats is associated with an impaired autoregulation of RBF, GFR, and Pgc (24, 40, 43, 48). More recently, we reported that transfer of 4.7-Mbp region of RNO1 (48) from BN rats into the FHH genetic background restored autoregulation of RBF and attenuated the development of glomerular disease but the mechanism and genes involved are unknown. The purpose of the present study was to narrow the region of interest for the impaired autoregulation of RBF by creating and phenotyping additional FHH.1BN congenic strains and to determine whether the impaired autoregulation of RBF in FHH rats is due to a lack of a myogenic response in the afferent arterioles secondary to an increase in K+ channel activity.

The results of the present study confirm our previous findings that autoregulation of RBF is impaired in FHH rats and it is fully restored in a dual congenic strain, C, which contains the 99.4-Mbp region of RNO1 from marker D1rat183 to D1rat76 along with a 4.7-Mbp region between markers D1rat376 and D1rat225 (48). To narrow the region further, two new double congenic strains, D and E, were created that cut the 4.7-Mbp region of interest in half. The phenotyping of these strains indicated that the gene(s) responsible for restoration of autoregulation of RBF in FHH.1BN rats is located in the 2.4-Mbp region closer to the q terminus of RNO1 that is introgressed in strain E. To exclude the possibility that the restoration of RBF autoregulation in strain E requires an interaction of BN genes in the two introgressed regions, we created and phenotyped a minimal congenic strain F in which the 2.4-Mbp region of interest alone was introgressed in the FHH genetic background. The results indicate that autoregulation of RBF is also fully restored in the FHH.1BN congenic strain F. This indicates that the gene of interest lies within the 2.4-Mbp interval that contains the 15 genes presented in Fig. 1.

Autoregulation of RBF is mediated by the myogenic response of the afferent arterioles acting in concert with tubuloglomerular feedback. Previous studies by Verseput et al. (44) suggested that TGF feedback responses are intact in FHH rats, which led to the current hypothesis that the impaired autoregulation of RBF might be due to alterations in the myogenic response of the afferent arterioles. To test this hypothesis, we studied whether the myogenic response of the afferent arterioles is altered in FHH rats and restored in FHH.1BN congenic strains. The results indicate that the myogenic response of the afferent arterioles was absent in FHH rats, and the diameter of the afferent arterioles increased in response to elevations in transmural pressure. In contrast, the myogenic response was restored in congenic strains E and F, and the afferent arterioles of these rats constricted in response to the same stimulus. The lack of a myogenic response of the afferent arterioles in FHH rats was not due to elevated vascular resistance or myogenic tone since removal of calcium from the bath had no effect on the diameter of the afferent arterioles in this strain. Nor was the impaired myogenic response secondary to structural changes, since the passive pressure-diameter relationships of the afferent arterioles were identical in FHH rats and the FHH.1BN congenic strain F in Ca2+-free media.

Previous studies by our laboratory and others indicate that the myogenic response of renal and cerebral arteries is associated with depolarization and inhibition of BKCa channel activity (9, 12). Therefore, patch-clamp studies were performed to further explore the mechanism of the impaired myogenic response in FHH rats. The results of these experiments revealed that whole cell K+ currents are elevated in VSMCs isolated from preglomerular arterioles of FHH rats relative to FHH.1BN congenic strains E and F. Single-channel analysis indicated that the elevated K+ current in FHH rats is associated with a marked increase in the open probability of the BKCa channels compared with those seen in the FHH.1BN congenic strain E. These strain differences were readily apparent when the cells were studied using high intracellular Ca2+ concentrations and maximally depolarized potentials to determine whether there was a difference in the Ca2+ or voltage sensitivity of the channels between the strains. The results indicate that the BKCa channels in renal VSMCs isolated from both FHH rats and the congenic strains are activated in response to membrane depolarization and elevations in intracellular Ca2+ concentration. However, BKCa channel activity was still significantly higher in VSMCs isolated from FHH rats vs. the congenic strain when studied under more physiological conditions using 100 nM intracellular Ca2+ concentration and −40-mV membrane potential. One could argue that baseline BKCa channel activity is very low under these conditions, so it is unlikely to hyperpolarize membrane potential and reduce opening of L-type Ca2+ channels. However, previous studies have indicated that since the BKCa channel has a very high conductance and the input resistance of VSMCs is so large (38), opening of a very small number of BKCa channels is sufficient to hyperpolarize the membrane potential. Thus in FHH rats the increase in BKCa channel function following elevations in transmural pressure may prevent the VSMC membrane from becoming sufficiently depolarized to increase calcium influx via voltage-gated calcium channels and thus impair the myogenic response. This mechanism is further supported by our observation that blockade of BKCa channels with iberiotoxin normalized the elevated K+ currents in renal VSMCs of FHH rats and restored the ability of afferent arterioles of FHH rats to constrict in response to elevations in transmural pressure. It has much less effect on K+ channel activity, and the myogenic response in the FHH.1BN congenic strains in which BKCa channel activity is not elevated. Overall, the results of the renal hemodynamic and patch-clamp studies indicate that the gene responsible for the impaired autoregulation of RBF in FHH rats acts by inhibiting the myogenic response of the afferent arterioles via a mechanism that enhances the activity of BKCa channels.

We previously suggested that impaired autoregulation of RBF in FHH may trigger the development of proteinuria and glomerular disease by elevating Pgc (48). Thus in the present study we compared the development of proteinuria and glomerular disease in FHH and the congenic strains in which autoregulation of RBF was restored. The present finding that proteinuria was significantly reduced in the FHH.1BN double congenic strains C and E relative to FHH between 9 and 21 wk of age is entirely consistent with this hypothesis. These double congenic strains also exhibited less glomerular injury and renal fibrosis than FHH rats. We also found that FHH.1BN congenic strain A which did not autoregulate RBF was not protected from the development of glomerulosclerosis or renal fibrosis. However, proteinuria was reduced, suggesting other genes and mechanisms may contribute to the protection from the development of proteinuria, but not glomerular injury in this strain. In this regard, the Rab38 gene is located within the 99.4-Mbp region of BN RNO1 introgressed in congenic strains A, B, C, D, and E. We have previously reported that there is a single base pair mutation of the ATG start site of transcription in FHH rats, and they do not express the Rab38 protein (32). Rab38 is involved in membrane trafficking, and loss of this protein mediates the coat color and bleeding disorder phenotype in FHH rats (8) and is thought to increase protein excretion by impairing reuptake and processing of filtered protein in the proximal tubule. Thus replacement of the defective FHH Rab38 gene with the BN wild-type allele likely explains why protein excretion is reduced in FHH.1BN strain A relative to FHH rats even though they do not autoregulate RBF and are not protected from glomerular injury. Correction of the mutated FHH Rab38 allele may also help explain the difference in protein excretion in FHH.1BN congenic strains C and E compared with strain F. Even though they all autoregulate RBF and are all similarly partially protected from the development of glomerular injury, only strain F has been reverted to the defective FHH Rab38 gene. Overall, the present findings are consistent with the view that the development of proteinuria and renal damage in FHH is a result of at least two interacting genetic defects on RNO1, i.e., the defect in the myogenic response resulting in increased transmittal of pressure to the glomerular capillaries to promote glomerular injury and increased filtration of protein acting in conjunction with knockout of the Rab38 gene in FHH rats, which is thought to decrease reuptake and processing of filtered protein in the proximal tubules.

BN rats were chosen as the donor strain for the creation of the consomic and congenic strains as they are the most genetically divergent strain relative to FHH rats with polymorphisms in ∼70% of markers across the genome. This facilitated the fine mapping of the genome in regions of interest in our congenic strains. However, the BN rat may have not been the best choice for the substitution since very little is known about steady-state autoregulation of RBF and or the myogenic behavior of renal arterioles of BN rats. Previous investigators have reported that BN rats exhibit impaired high-frequency dynamic autoregulation of RBF relative to spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) (46), suggesting a reduced myogenic responsiveness. BN kidneys are also more susceptible to hypertension-induced renal injury when transplanted into SHR (7). On the other hand, BN rats are resistant to renal disease and have an extended life span (27). Mattson et al. (26) have previously done a strain comparison of BN and FHH renal parameters and reported that BN rats are more resistant to the development of proteinuria and renal injury than FHH rats and that substitution of chromosome 1 from BN to FHH rats ameliorates renal injury in FHH.1BN consomic rats. Similarly, a study comparing BN to 10 other normotensive and hypertensive rat strains found that albumin and protein excretion, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and plasma creatinine are significantly lower in BN than in FHH and Dahl S rats (23). Moreover, the BN rat was simply used as a donor strain for the 2.4-Mbp region of interest on RNO1. Transfer of this region improved the myogenic response and corrected autoregulation of RBF in FHH rats. This simply means that other regions of the genome must be responsible for the differences in autoregulation of RBF previously reported in BN rats relative to SHR.

The results of the present study have established that the gene responsible for altering the myogenic response lies within the 2.4-Mb region of interest of RNO1 containing the 15 known and predicted genes listed in Fig. 1. Of these, only three genes, i.e., Xpnpep1, Add3, or Dusp5, have been reported to affect cardiovascular function and could be considered as potential candidate genes.

Ultimately, the identification of a causal gene requires evidence of a sequence variant that alters the expression or function of protein. Thus comparative sequence analysis was performed in FHH vs. BN rats to determine which of the positional candidate genes might contribute to the impaired myogenic response in FHH rats. More than 700 SNVs in 11 of the 15 genes in the 2.4-Mbp region were identified in FHH/EurMcwi rats vs. the BN reference sequence. However, only five of these SNVs were predicted to alter amino acids in the coding regions of three genes, Add3, Rbm20, and Shoc2.

Add3 is a membrane cytoskeletal protein that binds calmodulin (16) and is involved in the spectrin/actin network assembly. It serves as a substrate for PKC and Rho kinase (20). There are three forms of adducin; α, β, and γ, or Add1, 2, and 3, which are encoded on separate genes. Adducin proteins must form heterodimers or tetramers to function (14), and it has been shown that Add3 dimerizes with Add1 in the kidney (11). Rbm20 is reported to regulate splicing of titin, which is a sarcomeric protein that determines structure and biomechanical properties of striated muscle (17). Shoc2 is a RAS- and RAF-interacting scaffold protein that positively regulates signaling to ERK1/2 (15).

No studies have yet examined the direct involvement of Add3, Shoc2, or Rbm20 in renal myogenic response or K+ channel activity. Add3 has been reported to play a role in NaCl cotransporter (NCC) activity in luminal cells of the distal convoluted tubule by binding to phosphorylation sites on the NCC channel to stimulate NCC activity (10). Knockout of Add3 in mice (34) had no effect on blood pressure or red blood cell (RBC) and platelet function. Mutations in Add1 and 2 have been reported to cosegregate with hypertension (1–3, 13) and renal disease (28–29, 45) in patient populations. However, all of the work on the function of the Add family of proteins has focused on its role in the modulation of Na- K-ATPase activity and Na transport in the kidney and in regulation of the size and shape of blood cells rather than on the control of vascular function.

A comparison of the expression of the 15 genes and predicted genes in the region in the renal vasculature of FHH rats and the FHH.1BN congenic strain F indicated only two genes, Mxi1 and Rbm20, were differentially expressed in FHH compared with FHH.1BN strain F at 10 wk of age, although neither gene has any known action on vascular function. In addition, the expression of both of these genes was very low in the renal vasculature,<2.5 copies/1,000 β-actin copies, making it less likely that either of these genes is responsible for the impaired myogenic response of FHH rats.

Perspective

This study indicates that substitution of a 2.4-Mbp region of BN RNO1 restores the myogenic response in FHH.1BN congenic rats and that the mechanism of the impaired vascular reactivity in FHH is associated with an increase in BKCa activity in afferent arterioles. Three of the 15 genes in this region have sequence variants that could potentially alter the function of the proteins (Add3, Shoc2, and Rbm20), and two (Mxi1 and Rbm20) are differentially expressed in renal vessels isolated from FHH vs. that seen in congenic strain F. While mutations in the Add3 gene appear the most interesting at this time, further work is needed to determine which of these genes is responsible for altering the myogenic response in FHH rats and the mechanisms involved.

GRANTS

This work was funded in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants HL-036279 and DK-079306. M. Burke was supported by predoctoral training grant NIH 1T32HL105324 and predoctoral awards from the American Heart Association (11PRE7840002) and the NIH/NIA (1F31AG040000-01).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: M.B., J.M.W., and R.J.R. provided conception and design of research; M.B., M.R.P., F.F., Y.G., R.L., J.M.W., and J.L. performed experiments; M.B., M.R.P., A.B.S., J.L., and H.J.J. analyzed data; M.B. and R.J.R. interpreted results of experiments; M.B. and M.R.P. prepared figures; M.B. drafted manuscript; M.B., H.J.J., and R.J.R. edited and revised manuscript; R.J.R. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barlassina C, Citterio L, Bernardi L, Buzzi L, D'Amico M, Sciarrone T, Bianchi G. Genetics of renal mechanisms of primary hypertension: the role of adducin. J Hypertens 15: 1567–1571, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi G, Cusi D. The alpha-adducin polymorphism: a paradigm to analyse the genetics of primary hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant 10: 763–766, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bianchi G, Tripodi G, Casari G, Salardi S, Barber BR, Garcia R, Leoni P, Torielli L, Cusi D, Ferrandi M, Pinna LA, Baralle FE, Ferrari P. Two point mutations within the adducin genes are involved in blood pressure variation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 3999–4003, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DM, Provoost AP, Daly MJ, Lander ES, Jacob HJ. Renal disease susceptibility and hypertension are under independent genetic control in the fawn-hooded rat. Nat Genet 12: 44–51, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown DM, Van Dokkum RP, Korte MR, McLauglin MG, Shiozawa M, Jacob HJ, Provoost AP. Genetic control of susceptibility for renal damage in hypertensive fawn-hooded rats. Ren Fail 20: 407–411, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhari A, Kirschenbaum MA. A rapid method for isolating rabbit renal microvessels. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 254: F291–F296, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Churchill PC, Churchill MC, Bidani AK, Griffin KA, Picken M, Pravenec M, Kren V, St Lezin E, Wang JM, Wang N, Kurtz TW. Genetic susceptibility to hypertension-induced renal damage in the rat. Evidence based on kidney-specific genome transfer. J Clin Invest 100: 1373–1382, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Datta YH, Wu FC, Dumas PC, Rangel-Filho A, Datta MW, Ning G, Cooley BC, Majewski RR, Provoost AP, Jacob HJ. Genetic mapping and characterization of the bleeding disorder in the fawn-hooded hypertensive rat. Thromb Haemost 89: 1031–1042, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis MJ, Hill MA. Signaling mechanisms underlying the vascular myogenic response. Physiol Rev 79: 387–423, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimke H, San-Cristobal P, de Graaf M, Lenders JW, Deinum J, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. gamma-Adducin stimulates the thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransporter. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 508–517, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong L, Chapline C, Mousseau B, Fowler L, Ramsay K, Stevens JL, Jaken S. 35H, a sequence isolated as a protein kinase C binding protein, is a novel member of the adducin family. J Biol Chem 270: 25534–25540, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Regulation of the cerebral circulation: role of endothelium and potassium channels. Physiol Rev 78: 53–97, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrandi M, Salardi S, Tripodi G, Barassi P, Rivera R, Manunta P, Goldshleger R, Ferrari P, Bianchi G, Karlish SJ. Evidence for an interaction between adducin and Na+-K+-ATPase: relation to genetic hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H1338–H1349, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fowler VM. Identification and purification of a novel Mr 43,000 tropomyosin-binding protein from human erythrocyte membranes. J Biol Chem 262: 12792–12800, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galperin E, Abdelmoti L, Sorkin A. Shoc2 is targeted to late endosomes and required for Erk1/2 activation in EGF-stimulated cells. PLoS One 7: e36469, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner K, Bennett V. A new erythrocyte membrane-associated protein with calmodulin binding activity. Identification and purification. J Biol Chem 261: 1339–1348, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo W, Schafer S, Greaser ML, Radke MH, Liss M, Govindarajan T, Maatz H, Schulz H, Li S, Parrish AM, Dauksaite V, Vakeel P, Klaassen S, Gerull B, Thierfelder L, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Hacker TA, Saupe KW, Dec GW, Ellinor PT, MacRae CA, Spallek B, Fischer R, Perrot A, Ozcelik C, Saar K, Hubner N, Gotthardt M. RBM20, a gene for hereditary cardiomyopathy, regulates titin splicing. Nat Med 18: 766–773, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt SC, Hasstedt SJ, Coon H, Camp NJ, Cawthon RM, Wu LL, Hopkins PN. Linkage of creatinine clearance to chromosome 10 in Utah pedigrees replicates a locus for end-stage renal disease in humans and renal failure in the fawn-hooded rat. Kidney Int 62: 1143–1148, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iyengar SK, Fox KA, Schachere M, Manzoor F, Slaughter ME, Covic AM, Orloff SM, Hayden PS, Olson JM, Schelling JR, Sedor JR. Linkage analysis of candidate loci for end-stage renal disease due to diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: S195–S201, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshi R, Bennett V. Mapping the domain structure of human erythrocyte adducin. J Biol Chem 265: 13130–13136, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreisberg JI, Karnovsky MJ. Focal glomerular sclerosis in the fawn-hooded rat. Am J Pathol 92: 637–652, 1978 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuijpers MH, Gruys E. Spontaneous hypertension and hypertensive renal disease in the fawn-hooded rat. Br J Exp Pathol 65: 181–190, 1984 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwitek AE, Jacob HJ, Baker JE, Dwinell MR, Forster HV, Greene AS, Kunert MP, Lombard JH, Mattson DL, Pritchard KA, Jr, Roman RJ, Tonellato PJ, Cowley AW., Jr BN phenome: detailed characterization of the cardiovascular, renal, and pulmonary systems of the sequenced rat. Physiol Genomics 25: 303–313, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez B, Ryan RP, Moreno C, Sarkis A, Lazar J, Provoost AP, Jacob HJ, Roman RJ. Identification of a QTL on chromosome 1 for impaired autoregulation of RBF in fawn-hooded hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1213–F1221, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mattson DL, Dwinell MR, Greene AS, Kwitek AE, Roman RJ, Cowley AW, Jr, Jacob HJ. Chromosomal mapping of the genetic basis of hypertension and renal disease in FHH rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1905–F1914, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mattson DL, Kunert MP, Roman RJ, Jacob HJ, Cowley AW., Jr Substitution of chromosome 1 ameliorates l-NAME hypertension and renal disease in the fawn-hooded hypertensive rat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F1015–F1022, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mos J, Hollander CF. Analysis of survival data on aging rat cohorts: pitfalls and some practical considerations. Mech Ageing Dev 38: 89–105, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narita I, Goto S, Saito N, Song J, Ajiro J, Sato F, Saga D, Kondo D, Akazawa K, Sakatsume M, Gejyo F. Interaction between ACE and ADD1 gene polymorphisms in the progression of IgA nephropathy in Japanese patients. Hypertension 42: 304–309, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicod J, Frey BM, Frey FJ, Ferrari P. Role of the alpha-adducin genotype on renal disease progression. Kidney Int 61: 1270–1275, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Provoost AP. Spontaneous glomerulosclerosis: insights from the fawn-hooded rat. Kidney Int Suppl 45: S2–S5, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramensky V, Bork P, Sunyaev S. Human non-synonymous SNPs: server and survey. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 3894–3900, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rangel-Filho A, Sharma M, Datta YH, Moreno C, Roman RJ, Iwamoto Y, Provoost AP, Lazar J, Jacob HJ. RF-2 gene modulates proteinuria and albuminuria independently of changes in glomerular permeability in the fawn-hooded hypertensive rat. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 852–856, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudofsky UH, Magro AM. Spontaneous hypertension in fawn-hooded rats. Lab Anim Sci 32: 389–391, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sahr KE, Lambert AJ, Ciciotte SL, Mohandas N, Peters LL. Targeted deletion of the gamma-adducin gene (Add3) in mice reveals differences in alpha-adducin interactions in erythroid and nonerythroid cells. Am J Hematol 84: 354–361, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlick NE, Jensen-Seaman MI, Orlebeke K, Kwitek AE, Jacob HJ, Lazar J. Sequence analysis of the complete mitochondrial DNA in 10 commonly used inbred rat strains. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C1183–C1192, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiozawa M, Provoost AP, van Dokkum RP, Majewski RR, Jacob HJ. Evidence of gene-gene interactions in the genetic susceptibility to renal impairment after unilateral nephrectomy. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 2068–2078, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simons JL, Provoost AP, Anderson S, Troy JL, Rennke HG, Sandstrom DJ, Brenner BM. Pathogenesis of glomerular injury in the fawn-hooded rat: early glomerular capillary hypertension predicts glomerular sclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1775–1782, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toro L, Vaca L, Stefani E. Calcium-activated potassium channels from coronary smooth muscle reconstituted in lipid bilayers. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 260: H1779–H1789, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Twigger SN, Shimoyama M, Bromberg S, Kwitek AE, Jacob HJ. The Rat Genome Database, update 2007—easing the path from disease to data and back again. Nucleic Acids Res 35: D658–D662, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Dokkum RP, Alonso-Galicia M, Provoost AP, Jacob HJ, Roman RJ. Impaired autoregulation of renal blood flow in the fawn-hooded rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 276: R189–R196, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Dokkum RP, Jacob HJ, Provoost AP. Blood pressure and the susceptibility to renal damage after unilateral nephrectomy and l-NAME-induced hypertension in rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant 15: 1337–1343, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Dokkum RP, Jacob HJ, Provoost AP. Difference in susceptibility of developing renal damage in normotensive fawn-hooded (FHL) and August x Copenhagen Irish (ACI) rats after N(omega)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester induced hypertension. Am J Hypertens 10: 1109–1116, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Dokkum RP, Sun CW, Provoost AP, Jacob HJ, Roman RJ. Altered renal hemodynamics and impaired myogenic responses in the fawn-hooded rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 276: R855–R863, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verseput GH, Braam B, Provoost AP, Koomans HA. Tubuloglomerular feedback and prolonged ACE-inhibitor treatment in the hypertensive fawn-hooded rat. Nephrol Dial Transplant 13: 893–899, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang JG, Staessen JA, Tizzoni L, Brand E, Birkenhager WH, Fagard R, Herrmann SM, Bianchi G. Renal function in relation to three candidate genes. Am J Kidney Dis 38: 1158–1168, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, Ajikobi DO, Salevsky FC, Cupples WA. Impaired myogenic autoregulation in kidneys of Brown Norway rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F962–F969, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weichert W, Paliege A, Provoost AP, Bachmann S. Upregulation of juxtaglomerular NOS1 and COX-2 precedes glomerulosclerosis in fawn-hooded hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F706–F714, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams JM, Burke M, Lazar J, Jacob HJ, Roman RJ. Temporal characterization of the development of renal injury in FHH rats and FHH.1BN congenic strains. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F330–F338, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zou AP, Imig JD, Kaldunski M, Ortiz de Montellano PR, Sui Z, Roman RJ. Inhibition of renal vascular 20-HETE production impairs autoregulation of renal blood flow. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 266: F275–F282, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]