Abstract

We extract the thermodynamics of conformational changes in biomacromolecular complexes from the distributions of the dihedral angles of the macromolecules. These distributions are obtained from the equilibrium configurations generated via all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. The conformational thermodynamics data we obtained for calmodulin-peptide complexes using our methodology corroborate well with the experimentally observed conformational and binding entropies. The conformational free-energy changes and their contributions for different peptide-binding regions of calmodulin are evaluated microscopically.

Introduction

Thermodynamic stability of biomacromolecular complexes is pivotal in biological processes. Proteins are important in this context, for their functional properties quite often depend on their complexation with ions, ligands, and other macromolecules (1). The biomacromolecules, like proteins, are characterized by internal conformational degrees of freedom giving them specific structures. When a protein binds to a binding partner to form a complex in a solution, not only does the surrounding solvent undergo changes (2), but these large molecules themselves also experience structural modifications to stabilize the complex (3). It is not only that these changes take place simultaneously over different binding regions consisting of large number of conformational variables, but also that interactions between different groups of atoms are diverse. A microscopic understanding of biomacromolecular binding at the level of the binding regions, essential for understanding most of the biophysical and biochemical processes in detail, is thus one of the most challenging problems (4,5).

The thermodynamic characterization of the binding regions requires both entropy and free energy contributions. Experimentally, the binding entropy and the binding free energy have been measured by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) (6). However, this macroscopic method cannot yield the information on the changes of individual binding regions. With the advent of NMR relaxation experiments (7–10) to measure the conformational entropy costs in biomolecular complexes, the role of conformational changes in the binding regions has been emphasized.

Computer simulations provide a useful route to extract thermodynamic data (11). The computer simulations (12–15) used to estimate the conformational entropy from the normal modes (16) associated with atomic vibrations or quasiharmonic (QH) analyses (17) have been numerically very challenging, while the approaches based on purely statistical scoring functions from the crystal structure databases (18,19) are devoid of microscopic details. Atomic Cartesian coordinates often are not suitable to capture all possible bond rotations, thus providing poor estimates (20) of conformational entropy. Furthermore, these methods are often limited due to huge collective motional correlations inherent to changes in atomic Cartesian coordinates. Recently, the protein dihedral angles have been widely used as the conformational variables. Multidimensional histograms of the dihedral angle distributions have been constructed to estimate the conformational entropy (21). However, such calculations are computationally demanding, thus limiting the applicability to small systems only. A detailed approach (22) incorporating correlations among the dihedral angles up to different order (pairwise correlations, three-point correlations, and beyond) has shown that ∼80% of the conformational entropy for different small molecules could be recovered by neglecting all sorts of correlations. In biomolecules, the long-ranged dihedral correlations have been found (23,24) to be negligible except for some short-ranged correlations among the side-chain torsions. These observations practically illustrate the importance of completely reduced one-dimensional histograms (25,26) based on a single dihedral angle. A recent Monte Carlo based approach (27) has considered a fixed-backbone implicit solvent model to probe the contributions of side-chain entropies toward the binding entropy for protein-ligand interactions. Their estimates correlate quite well with the ITC data (28) for several Calmodulin-target peptide complexes.

Accurate and efficient estimation of conformational free energy has proved quite challenging to date. The conformational states of a small biomolecule have been explored via UV resonance Raman measurements (29) where the free energy difference between two states has been calculated by the population ratios of those two states. Computational methodologies for calculation of conformational free energies are of two types:

-

1.

Estimating the absolute free energies of a conformational state; and

-

2.

Evaluating the free energy differences between two states.

One recent example of the first type is the reference system method (30). It is an implicit solvent model based on the description of a reference system for a biomolecule using the internal or Cartesian coordinates. Though this method gives good measures of conformational free energies for dipeptides, application to larger systems is computationally very costly. A number of methods belong to the second type; for instance, the confinement method (31), a variation of the normal mode analyses and the deactivated morphing method (32), based on nonphysical transformations between two conformational states where all the interactions are turned off before the change. Nonequilibrium molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (33) have been employed, based on a differential fluctuation theorem (34), to evaluate free energy differences with implicit solvent contributions. Explicit solvent MD simulations (35) have also been used to calculate the free energy differences between two conformational states of a polymer chain, using a path variable connecting two states on the configurational phase space. A common limitation of all these approaches is their inefficiency to study medium-to-large biomolecular systems and focus on individual binding regions.

With this backdrop, it is fair to say that a simple and computationally efficient method to calculate the conformational thermodynamics including both the entropy and free energy is yet lacking. Here we show that the histogram-based methods can yield the desired information simultaneously from a single set of simulations, unlike the existing expensive computation methodologies that provide the entropy and free energy separately. The connection between the underlying thermodynamics and the histogram can be understood as follows: Because the histograms can be treated as the probability of finding the system in a given conformation, they can be interpreted as given by the Boltzmann factors of the corresponding effective free energies, while the entropies are given by the Gibbs formula (27). Here, we extract thermodynamics of the conformational changes from the histograms of the dihedral angles, which can be sampled efficiently from the equilibrium trajectories from all-atom MD simulations of a biomacromolecular complex and its components in their respective free states, all being in an explicit solvent.

We apply our technique to experimentally well-studied Calmodulin-peptide complexes. Calcium (Ca2+) saturated Calmodulin (CaM) is the primary mediator of target protein activities responding to changes in intracellular calcium levels (36). Upon Ca2+-saturation, CaM undergoes subtle conformational changes (37,38), exposing its target-binding hydrophobic faces to preferentially amphiphilic target peptides (6). CaM (Fig. 1 a) has two globular domains linked by a long helix (helix 4, residues 68–92) which gets deformed to wrap around a peptide while binding (Fig. 1 b). The huge variety of proteins containing CaM target sequences include a large number of regulatory enzymes (39,40), e.g., protein kinases, phosphodiesterases, cyclases, etc. Here we consider five such peptides: CaM target sequences of smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase (smMLCK) (41); the neuronal and endothelial nitric oxide synthases (nNOS and eNOS, respectively) (42); the calmodulin kinase I (CaMKI) (6); and the calmodulin kinase kinase (CaMKK) (43). For all these CaM-peptide complexes, the ITC data (6,28,41) and conformational entropy changes (ΔSconf) measured via NMR relaxation experiments are known (28,44–46). Frederick et al. (28) reports the ΔSconf for these CaM-peptide complexes based on the QH treatment of the distributions of the long-axis order-parameters () of the methyl groups. increases from zero to unity as rotation of the methyl group about the long-axis gets restricted indicating lowering of entropy. According to their observation, total changes in conformational entropy () are linearly correlated with the total binding entropy () for the complexes. In a more recent work (44), ΔSconf of the same complexes has been estimated in a model-independent manner from postulating that ΔSconf for CaM and the targets are linearly related to 〈Δ〉, the average changes in residue-weighted . They consider 〈Δ〉 as a general measure of changes in local disorder at any residue. They find much higher ΔSconf compared to Frederick et al. (28), indicating limitations of QH approaches. Significant linear correlation has been observed between ΔSconf for CaM and , while ΔSconf for peptides are nearly uncorrelated.

Figure 1.

Cartoon representations of CaM in (a) Ca2+ saturated state and (b) CaM bound to a target peptide, smMLCK (PDB:1CDL). The protein is in open representation and the peptide is in solid representation. The different helices are marked in both the structures. The methyl order parameters are shown for (c) CaM and (d) peptide in the eNOS complex. Here, the experimental data (exp) are plotted against the theoretical (calc) values. (Solid line) = (calc); (dotted line) (exp) = (calc) + 0.2; (dashed line) (exp) = (calc) − 0.2. Different types of methyls are marked by symbols shown in the figure.

In this article, we calculate the values of the complexes from the simulated trajectories, which agree with the available experimental data (44) reasonably well. Subsequently, we estimate ΔSconf of the complexes and the components correctly and recover the experimental observations. Further, we estimate the conformational free energy cost of binding to predict different contributions of the individual binding regions of CaM. Our calculations show that the deformations in helix 4 to wrap around the peptides cost huge free energy and entropy. The unfavorable changes are outweighed by the favorable changes at different binding regions dominated by the interactions among the charged residues and the hydrophobic residues.

Materials and Methods

Thermodynamics from distribution of conformational variables

For a system with conformational variable set {ξi}, the normalized probability distribution is given by

| (1) |

where kB is the Boltzmann constant; T is the absolute temperature; ({ξi}) is the Hamiltonian; and Z is the partition function of the system. The reduced probability distribution for a given conformational variable ξ can be obtained by integrating over the other variables in Eq. 1

| (2) |

which defines the effective free energy G(ξ) or the potential of mean force (47) associated with ξ.

We consider ξ ≡ (θ, τ) where θ and τ are the dihedral angles for protein p and ligand l, respectively. Subsequently, we use the subscripts p+l, p, and l to indicate quantities associated with the complex, the protein, and the ligand, respectively, while the superscripts c and f denote the bound and free state, respectively. We define the following effective free energies from Eq. 2:

| (3) |

Therefore, the free energy change for ξ due to complexation is

| (4) |

The correlation between any two dihedral angles ξi of ith residue and ξ′j of jth residue is defined as (26)

| (5) |

where the s = |i − j| and the angular brackets denote ensemble average. If correlations are negligibly small, the conformational variables can be considered independent. Then we write

to give us from Eq. 4,

| (6) |

so that the thermodynamics is given separately in terms of the individual dihedrals. If we sum over all the dihedral angles of protein and peptide we get the total conformational free energy change:

| (7) |

We can express differently to illustrate the nature of approximations in our calculations. Let z(ξ) be the partition function corresponding to effective free energy G(ξ) = −kBT ln z(ξ). Therefore, z(ξ) = exp(−G(ξ)/kBT) = P(ξ)Z, from Eq. 3, P(ξ) being the probability distribution for ξ. Defining z(ξ) for the protein variables θ and ligand variables τ in free and complex states we can write

| (8) |

which, using Eq. 7, simplifies to

| (9) |

where and so on. The term in square brackets in Eq. 9 is the conformational contribution to the equilibrium-binding constant. Here we assume that the other degrees of freedom like bond angles and bond vibrations change very little in the complex compared to the free states and they are decoupled from the dihedral angles, thus cancelling out from the ratio in Eq. 9. The ratio of partition functions in Eq. 9 resembles that used earlier (48) to define the standard free energy of binding of a receptor to a ligand. However, we consider here only a restricted set of internal degrees of freedom associated with equilibrium fluctuations of the dihedrals. Because we focus only on the conformational part of the thermodynamics, we do not consider the solvation components; however, the effects of solvent on dihedral distributions have been taken into account through explicit solvent molecules. We also ignore the external contributions to the thermodynamics as in Marlow et al. (44), assuming that they remain unchanged for all the complexes due to the similarities in structures of the complexes and length and binding affinities of the peptides.

The normalized probability distribution of a protein dihedral θ is given by the histograms Hcp(θ) and Hfp(θ) and that for a ligand dihedral by Hcl(τ) and Hfl(τ) in the bound and the free states, respectively. They can be generated from equilibrium trajectories obtained by molecular simulations. The peak of the histogram defines the equilibrium value of the relevant dihedrals. Then the equilibrium conformational free energy cost associated with any protein dihedral θ is

| (10) |

where the subscript max denotes the maximum of histogram. Such a treatment is sufficient because the population at the base of a peak is insignificant (1–10%) compared to that at the maximum for a typical histogram.

The free energy contributions from the neighborhood of the maximum can be accounted for within a QH expansion about the maximum. We expand a histogram H(θ) about the maximum at θ = θ0 up to the quadratic term,

where H″(θ0) = |C(θ0)|, the curvature near the maximum. Therefore, the effective free energy for θ can be written using Eq. 3 as

| (11) |

Equation 11 can be rearranged to give

where x = θ − θ0 and . For Bx2 ≪ 1, we get

This can be further approximated as to yield

| (12) |

Considering contributions from all x, Eq. 12 can be written as

This integration essentially implies that the contributions around the peak have been taken into account at the QH level. The integration gives the modified free energy

| (13) |

The corresponding free energy difference is then

| (14) |

Similar expressions like Eqs. 10 and 14 can be written for the peptide dihedrals as well.

For multimodal histograms, we compute the free energies by taking an average, weighted by the maximum values of the peaks. For a particular dihedral ξ with multimodal histograms in both free and complex states, the free energy cost is given by

where

representing the free energy cost for transition from ith peak in free state to jth peak in the complex state and

the respective weights.

The conformational entropy for a particular dihedral can be estimated directly using the Gibbs entropy formula, given for a dihedral ξ by

| (15) |

where the sum is taken over the histogram bins i with a nonzero value of Hi(ξ). Therefore, the conformational entropy change for the dihedral is

| (16) |

In the QH limit, the entropy associated with the histogram of any dihedral ξ can be expressed in terms of the entropy of a harmonic oscillator fitted to the peak. The frequency of the oscillator of mass μ and force constant k is given by . Therefore, entropy is given by

with h being the Planck’s constant. If Cf and Cc are the curvatures near maxima for the dihedral-histogram in free and complexed states, respectively, we have

| (17) |

For multipeak histograms, QH entropies are obtained by weighted average over the peaks with finite curvature around the maxima.

The thermodynamics of conformational changes of a given residue are finally obtained by adding all the associated dihedral contributions. ΔGconf and ΔSconf of a given region are computed by adding the contributions of all residues in that region. Similarly, the total changes are calculated by adding all residue contributions.

Simulation details

We perform an all-atom MD simulation of the free protein, free peptide, and the complex in explicit water with counterions to ensure electroneutrality. Simulations are done with the NAMD program (49) at 308 K and 1 atm pressure in isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble under standard protocols (50), using the CHARMM force field (51), periodic boundary conditions, and 1 fs time-step. The initial configurations are chosen from the following Protein Data Bank (PDB) entries: PDB:1CDL (smMLCK); PDB:1NIW (eNOS); PDB:2O60 (nNOS); PDB:2L7L (CaMKI); PDB:1CKK (CaMKK); and PDB:1CLL (free CaM). The peptide coordinates in the complexes are taken as the initial configurations of the free peptide simulations. We keep the number of total particles including water, pressure, and temperature fixed for each case to make the simulated ensembles equivalent. We run 50-ns-long simulations to capture most of the protein motions and peptide motions relevant for binding. The equilibration is ensured in any run by monitoring the root-mean-square deviation of the biomolecules, shown in the Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material. We analyze the data at two levels: First, we consider the trajectories up to 10 ns because the conformational entropy is dominated primarily by subnanosecond side-chain motions (28,44), and calculate the histograms for the dihedral angles from equilibrated configurations sampled beyond 2 ns. Second, we consider the longer 50-ns trajectory and compare data with the shorter run.

Results

We compare our calculated methyl (see Fig. S2) order-parameters (calc) (see Methods in the Supporting Material) to the experimental data (exp) (44) in Fig. 1 c (CaM) and Fig. 1 d (peptide) for a representative case: eNOS-complex. Most of the Ala, Met, Val, and Thr methyls are close to the perfect correlation line ((exp) = (calc)) or within the (exp) = (calc) ± 0.2 region, indicating reasonable agreement between the theoretical and experimental values. There are some overestimations, mostly for the Leu methyls, as expected for force-field based MD simulations (52,53). Results of other complexes are shown in Fig. S3 and Fig. S4.

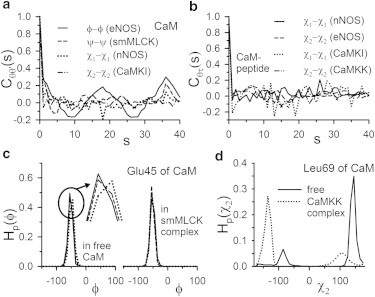

We choose the backbone dihedrals ϕ, ψ and the side-chain dihedrals χ1, χ2, χ3, χ4, and χ5. Fig. 2, a and b, shows the equilibrium correlations (Eq. 5) among different dihedrals. The data shown in Fig. 2 a for different dihedrals of CaM in various complexes and the cross-correlations between CaM and peptide dihedrals shown in Fig. 2 b indicate nearly zero correlations among the dihedrals, which is consistent with the earlier observations (24,26). More dihedral-correlations are shown in Fig. S5. In absence of significant correlations, we consider the histograms of the individual dihedrals for the calculation of thermodynamics. The histograms are calculated over 10 sets of equilibrated configurations each having 1000 samples from different parts of the trajectory. Fig. 2 c shows three such histograms in free and complex states for the dihedral angle ϕ of CaM-residue Glu45 in the smMLCK complex.

Figure 2.

Correlations Cξξ′(s) between dihedral angle ξ of one residue and ξ′ of another residue at separation s between the locations of the residues. (a) Correlations among dihedrals belonging to CaM only, in different complexes. (Solid line) Correlations among ϕ-dihedrals (ξ = ξ′ = ϕ) of CaM in the eNOS complex. Similarly, the other plots are for correlations among ψ-angles in smMLCK-complex (dashed), χ1 angles in nNOS-complex (dotted), and χ2 angles in CaMKI-complex (dash-dot). (b) Cross-correlations among protein and peptide side-chain dihedrals among χ1 angles (ξ = ξ′ = χ1) in nNOS complex (solid), χ2 angles in eNOS complex (dashed), χ1 angles in CaMKI-complex (dotted), and χ2 angles in CaMKK-complex (dash-dot). (c) Representative histograms of ϕ-dihedral of CaM residue Glu45 in free and bound form in smMLCK-complex. (Inset) Near-peak region for the free case. Three convergent histograms are shown (solid, dashed, and dotted lines, respectively) sampled from different parts of the MD trajectory. (d) Multimodal histogram of CaM residue Leu69 in free and bound form in the CaMKK complex.

The similarities of these histograms indicate the convergence of thermodynamic quantities, for instance, conformational entropies, calculated based on them (see Fig. S6). Due to equivalence of the samples, we compute the overall changes in entropy and free energy via a flat average over the entire equilibrium trajectory. All the backbone dihedrals exhibit sharply single-peaked histograms with the maxima around the equilibrium values in the initial configuration (PDB coordinates). Multimodal histograms have been mostly observed for the side-chain dihedrals as shown in Fig. 2 d for χ2 of CaM residue Leu69 indicating different rotameric states. The other examples are Asp118 and Phe65 in CaM (see Fig. S7).

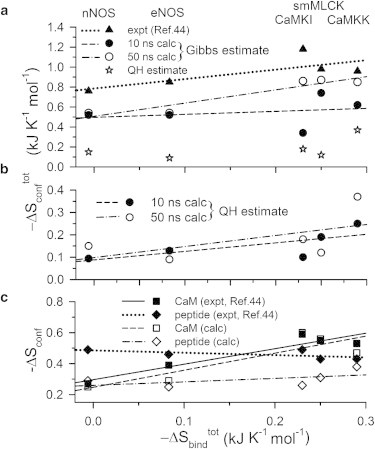

In Fig. 3, we compare our calculated total conformational entropies of the complex with the available experimental results. We consider the results calculated using the Gibbs formula (Eq. 16) (Fig. 3 a). Here we compare the 10-ns and 50-ns data with the experimental (solid triangles) reported in Marlow et al. (44). Both the theoretical and experimental are plotted against the corresponding from ITC (28), showing linear correlations between and . The 10-ns data (solid circles) can account for the experimental trend (solid triangles) except for CaMKI and CaMKK. However, the best-fit correlation line has slope m = 0.3 and linear correlation coefficient R = 0.3, which are far from the experimental data (m = 0.95 and R = 0.75). The 50-ns data (open circles) provide an overall better estimate for all cases where the correlation line (m = 1.3 and R = 0.95) agree quite well with the experimental data. One reason for the underestimation by the 10-ns data for CaMKI and CaMKK could be the fact that the initial configurations for simulations in these two cases are NMR-determined structures. For other complexes, the initial structures are from crystallographic data where the 10-ns and 50-ns data hardly make any difference. NMR data generate an ensemble of structures, unlike the only structure obtained from crystallography. Therefore, equilibration of the solution-NMR structures may not have been completed properly in the 10-ns simulation run. Fig. 3 a further shows that from QH approximation (Eq. 17) (open stars) leads to underestimation, although the linear correlation between and is observed here as well (Fig. 3 b).

Figure 3.

(a and b) Comparison of theoretical and experimental for CaM-peptide binding plotted against the experimental total binding entropy obtained from ITC measurements (28): (a) calculated using the Gibbs formula (Eq. 16) from the 10-ns runs (solid circles), the 50 ns runs (open circles) along with the experimental data from Marlow et al. (44) (solid triangles). (Lines) Best linear fits of the 10 ns (dashed), 50 ns (dash-dot), and the experimental data (dotted). (Stars) 50 ns data in QH limit. (b) Calculated from 10 ns simulations (solid circles) and 50 ns simulations (open circles) using the QH approximation (Eq. 17). The best linear fits are shown for 10 ns (dashed, m = 0.39, R2 = 0.53) and 50 ns (dash-dot, m = 0.47, R2 = 0.32). (c) The conformational entropy contributions of the components from 50-ns run plotted against : CaM contributions (open squares) with the best fit line (dashed) and peptide contributions (open diamonds) with the best fit line (dash-dot). The corresponding experimental data (44) are also shown for CaM contributions (solid squares) with the best fit line (solid) and peptides (solid diamonds) with best fit line (dotted).

The (in kJ K−1 mol−1) for all the side-chain dihedrals in the complexes showing multipeak histograms are −0.43 (nNOS), −0.23 (eNOS), −0.57 (CaMKI), −0.56 (smMLCK), and −0.58 (CaMKK) obtained using the Gibbs formula. Such multimodal histograms contribute >60% of the total conformational entropy stabilizations of the complexes, indicating the importance of the redistributions of populations among various side-chain rotamers in the binding. In Fig. 3 c, we report the contributions of the CaM and peptide separately in the complexes, estimated from the 50-ns runs. The CaM contributions show good agreement between the theoretical (open squares) and the experimental data (solid squares). The best fit theoretical line (dashed, m = 1.1, R = 0.88) almost quantitatively matches the experimental correlation line (solid, m = 1.0, R = 0.94) (44). We find CaM in CaMKI to be entropically most stabilized and least stabilized in nNOS, which supports the same experimental observations (44). In the same line for the peptide, we get similar entropic stabilization for all the cases.

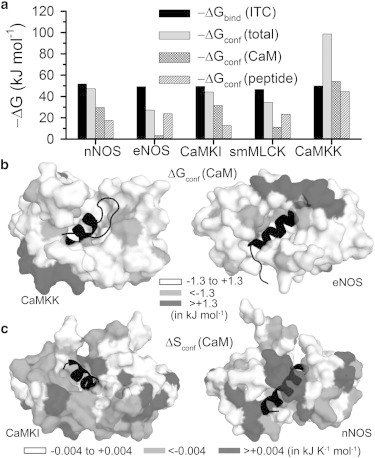

The total conformational free energy changes calculated from histogram maxima (Eq. 10) and the contributions of the components are shown in Fig. 4 a along with the experimental total binding free energy cost (28). The values fall in a very narrow window (45–52 kJ mol−1). Our estimated also lie in a similar range (27–47 kJ mol−1) for four complexes except CaMKK, where the extent of stabilization is nearly double. This separates out CaMKK from the others, which may be a signature of its opposite binding orientation compared to the other four: While binding to CaM, the N-terminal of four of the peptides interact with the C-terminal of CaM, except CaMKK, for which C-terminal of the peptide interacts with the C-terminal of the protein, and so on (43). We also estimate the contributions to due to finite width of the histograms using Eq. 14, to be only 1–5% of the estimate from histogram maxima for all the complexes except smMLCK for which this difference is ∼15%. Although it seems from data that all the peptides exhibit similar affinity to CaM, the conformational contributions of the components bring out a different picture. The protein is conformationally most stabilized in the CaMKK complex, while least stabilized in the eNOS complex. The peptide, on the other hand, is stabilized similarly in all the cases except in the CaMKK complex.

Figure 4.

(a) Calculated along with the individual protein and peptide contributions shown using a bar-graph. The experimental is also shown. Surface representations of CaM-peptide complexes showing the residuewise (b) ΔGconf of CaM for the cases where the protein is most stabilized (CaMKK) and least stabilized (eNOS); (c) ΔSconf of CaM in most ordered (CaMKI) and disordered (nNOS) complexes. The residues stabilized by ΔGconf < −1.3 kJ mol−1 and ordered by ΔSconf < −0.004 kJ K−1 mol−1 are light-shaded and those with ΔGconf > +1.3 kJ mol−1 or ΔSconf > +0.004 kJ K−1 mol−1 are dark-shaded. The residues undergoing minor changes are in open representation. Peptide is in solid cartoon representation.

The thermodynamic changes at each protein residue are shown by surface representations in Fig. 4, b and c, for the most and least stabilized complexes, both free energetically and entropically. In Fig. 4 b, CaMKK and eNOS complexes are shown, where the light-shaded residues are stabilized, the dark-shaded residues are destabilized, and the open residues undergo a marginal change in conformational free energy. In Fig. 4 c, we show the entropy changes for CaMKI and nNOS complexes where the light-shaded residues are ordered while the dark-shaded residues are disordered in the bound protein compared to the free state.

Next, we examine closely the changes in the peptide binding regions (PBR) of CaM. If any atom of a protein residue comes within a distance of 5 Å of a peptide atom, we consider the corresponding residue to be part of the PBR. The thermodynamic contribution of a PBR is obtained by summing over the contributions of the residues that are part of the PBR. Different PBRs show different degree of thermodynamic stabilizations. The residues in helix 4 responsible for the wrapping of the peptide constitute the most destabilized PBRs. The deformation of helix 4 occurs for different peptides at slightly different locations where a coiled region is formed due to loss of a secondary structure element. For instance, in the nNOS complex, the coil is produced over the residues 77–83 (ΔGconf = +19.8 kJ mol−1 and ΔSconf = +0.07 kJ K−1mol−1), whereas it is 73–76 for smMLCK (ΔGconf = +11.7 kJ mol−1 and ΔSconf = 0.0 kJ K−1 mol−1) and 76–81 for CaMKK (ΔGconf = +20.6 kJ mol−1 and ΔSconf = +0.08 kJ K−1 mol−1). For the other two complexes, these regions are residues 77–83 with the changes being for eNOS (ΔGconf = +15.6 kJ mol−1 and ΔSconf = +0.08 kJ K−1 mol−1) and CaMKI (ΔGconf = +12.8 kJ mol−1 and ΔSconf = +0.12 kJ K−1 mol−1).

The huge free energy cost at the destabilized PBR is compensated by the favorable changes at the other PBRs and the peptides. The changes at the most stabilized PBRs for different complexes are shown in Table 1. Furthermore, CaM being an acidic protein interacting with all these peptides rich with basic residues, the electrostatic contributions are also expected to play an important role. We analyze from our calculations the contributions of these protein-peptide interactions in some highly stabilized PBRs. It is quite apparent from Table 1 that the charged and polar residue contributions dominate in all the cases, for both conformational free energy as well as entropy. The highly stabilized common binding regions in all the complexes are CaM-residues 11–19 (EFKEAFSLF); 36–41 (MRSLGQ); 42–50 (NPTEAELQD); 52–55 (INEV); 84–92 (EIREAFRVF); and 105–116 (LRHVMHNLGEKL). Evidently, these PBRs are rich in charged (E, D, R, K, H) and polar (S, Q, N, T) residues, making them the dominating stabilizing factor in CaM-peptide complexes. Table 1 also shows that there are stabilized residues with hydrophobic side chains (F, A, L, I, V, M) undergoing substantial conformational stability in the binding, as pointed out earlier from structural analyses (6) and recent NMR studies (45).

Table 1.

Conformational thermodynamics of different highly stabilized peptide binding regions of CaM in the complexes

| Peptide | CaM residues | ΔGconf (kJ mol−1) |

ΔSconf (kJ K−1 mol−1) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | CPRC (%) | HRC (%) | Total | CPRC (%) | HRC (%) | ||

| nNOS | 11–19, 36–41, 42–50, 84–92 | −18.2 | 43 | 24 | −0.1 | 31 | 29 |

| eNOS | 11–19, 117–123 | −6.5 | 64 | 14 | −0.05 | 76 | 4 |

| CaMKI | 7–10, 36–41, 42–50, 52–55, 71–76, 84–92, 105–116 | −32.9 | 57 | 26 | −0.44 | 68 | 15 |

| smMLCK | 11–19, 36–41, 52–55, 84–92, 105–116, 117–123 | −9.0 | 59 | 14 | −0.27 | 65 | 12 |

| CaMKK | 7–10, 11–19, 36–41, 42–50, 52–55, 84–92, 105–116, 124–128 | −41.3 | 49 | 27 | −0.24 | 49 | 22 |

| DAPK2 | 11–19, 35, 36–41, 42–50,124–128 | −17.9 | 64 | 15 | −0.24 | 55 | 23 |

The residue numbers according to the PDB indices are listed. The conformational free energy and entropy contributions of these binding regions are shown along with their percentages of charged and polar residue contributions (CPRC) and hydrophobic residue contributions (HRC).

Discussion

The agreement between our results on ΔSconf and those of Marlow et al. (44) has a strong implication. Marlow et al. (44) connects the NMR data on 〈Δ〉, the average changes of residue-weighted , to ΔSconf for several CaM-peptide complexes. By definition,

where nCaM and npep are the numbers of residues in CaM and peptide, respectively,

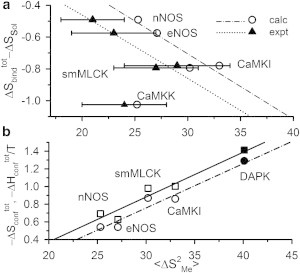

where the average is taken over the available methyl groups in the respective system. The underlying assumption is that 〈Δ〉 is a measure of conformational disorder at any residue so that is a dynamical proxy for conformational entropy. This identification heavily relies on the linearity of ( − ΔSsol) with experimental 〈Δ〉 (ΔSsol being the calculated solvent contribution (44)) as shown in Fig. 5 a (dotted line, m = −0.039) that leads to linear dependence of on 〈Δ〉 with the same slope.

Figure 5.

(a) ( − ΔSsol), taken from Marlow et al. (44), plotted against experimental values (44) (triangles with error bars) and our calculated (open circles) values of 〈Δ〉. CaMKK is an outlier to the experimental best fit line (dotted, m = −0.039, R = 0.97) as well as the best fit through the calculated data (dash-dot, m = −0.042, R = 0.98). (b) Plot of − (circles) and −/T (squares) versus 〈Δ〉 from our calculations excluding CaMKK. Both the best fit lines (dash-dot for −, and solid for −/T) have m = 0.05. (Solid symbols) Data for the CaM-DAPK2 complex.

We calculate 〈Δ〉 from our simulation data on to check whether we could recover the experimentally observed linearity between ( − ΔSsol) and 〈Δ〉. The estimation of 〈Δ〉 from simulation is somewhat tricky. Although and remain very similar over the entire equilibrium trajectory, and converge slowly with convergence achieved typically beyond 12 ns (see Fig. S8). Such slow convergence is probably due to the presence of fewer methyl groups than in protein. The convergence for smMLCK is the poorest, for it has the least number (8) of methyl groups. This slow convergence for peptides leads to pronounced variations in 〈Δ〉 arising due to large multiplicative factors (nCaM = 148 and npep ∼ 20). Therefore, we consider only the long-time part of the trajectory to estimate 〈Δ〉. The ( − ΔSsol) from Marlow et al. (44) is linear with our calculated 〈Δ〉 (dash-dot line in Fig. 5 a; m = −0.042) excluding the data for CaMKK, which is an outlier in the experimental plot as well.

A microscopic justification for the use of as a dynamical proxy of conformational entropy in Marlow et al. (44) is provided by Fig. 5 b showing the linearity between our estimated (open circles) from dihedral distributions and simulated 〈Δ〉 (dash-dot line) with very similar slope (m = −0.050). Because our calculated values are very similar for different complexes except CaMKK, the conformational enthalpy changes ( = + ) should also have the same linearity with 〈Δ〉 as for thermodynamic consistency. We find this indeed is the case in Fig. 5 b, also showing the plot of /T values (open squares) of the complexes, excluding the outlier CaMKK.

Efficiency of any computational method depends on the simulation length to generate convergent thermodynamics. Our method is highly advantageous from that point of view, as indicated by the convergence of the histograms and conformational entropy (see Fig. S6) obtained from different parts of trajectory. The convergence has been achieved with shorter runs (10 ns) where initial configurations are taken from available crystal structures, while longer runs (50 ns) are required for the solution-NMR derived initial structures. The reduced histograms can also be generated from suitable model initial structures in the absence of PDB structure. However, the equilibration may depend on how the initial conditions are constructed.

As far as the efficiency of the method used to extract ΔSconf from the histograms is concerned, both the Gibbs formula and QH approximation are computationally comparable when the dihedrals are uncorrelated. Although the Gibbs formula is more accurate, the QH approximation is often used for its simplicity and as a benchmark tool for analyses with probability distributions of conformational variables. However, the QH approximation underestimates ΔSconf in our studies. It may be stressed that we use the QH approximation to incorporate the free energy contributions for conformations away from the equilibrium value marked by histogram maxima. Such treatment is meaningful due to the low weight of those conformations compared to the equilibrium conformation.

Experimentally, large-amplitude rigid-body domain motions have been observed for CaM in timescales much longer than 50 ns (54). Due to high conservation of the compact structures among all the complexes, these domain motions are not expected to vary much from one to another. Such motions of timescale of approximately milliseconds (54), in both free and complex states, would be decoupled from the subnanosecond, highly localized side-chain motions (44) that control the conformational thermodynamics. Even if we consider the entropy change associated with such motions, given by the logarithm of the ratio of two high frequencies in free and complex states, the contribution would be insignificant.

The uncorrelated dihedral angles reduce the computation cost enormously. However, when the correlations of the conformational variables cannot be neglected, the correlation matrix can be diagonalized to obtain the uncorrelated basis and used for the calculations. For any two conformational variables ξi and ξj, the covariance matrix is symmetric because Cij = Cji. Therefore, one can determine a set of uncorrelated variables by diagonalizing the covariance matrix,

where [λij] is the transformation matrix found by the eigenvalues. The maximum of a sharp histogram of a given variable is essentially equal to its mean and the curvature given by the variance. The mean of the transformed variable,

and the variance,

We apply our approach to make predictions on the conformational thermodynamics of binding of a target peptide from death-associated protein kinase (DAPK2) (55) to CaM. Here, the S308D mutant of DAPK2 has been considered with a high-resolution crystal structure (PDB:1ZUZ) and known ITC data (= −39.5 kJ mol−1 and = −0.28 kJ K−1 mol−1 at 300 K) (55). However, nothing is known regarding the conformational entropies of this system to the best of our knowledge. We perform 20-ns runs for this complex and the free peptide as we have seen earlier that shorter runs are sufficient to capture the conformational thermodynamics if crystal structures are employed as starting configurations. The residuewise data are given in Fig. S9. We find = −1.29 kJ K−1 mol−1 using the Gibbs formula where the CaM and peptide contributions are −0.98 and −0.31 kJ K−1 mol−1, respectively. The values follow the same linear scaling with 〈Δ〉 as the other complexes, as shown by the solid circle in Fig. 5 b. We get = −38.1 kJ mol−1 with CaM and peptide contributions being −15.4 and −22.7 kJ mol−1, respectively. These free energy values are very similar to the case of smMLCK. The calculated (solid square) falls, just like , on the line drawn for other complexes in Fig. 5 b. Residues 77–83 constitute the maximum destabilized PBR in DAPK2 complex with very similar changes as earlier: ΔGconf = +21.2 kJ mol−1 and ΔSconf = +0.02 kJ K−1 mol−1. The changes of highly stabilized PBRs are listed in Table 1 along with the associated contributions of charged and hydrophobic residues.

Conclusion

To summarize, we have shown that the thermodynamic changes in biomacromolecular conformations can be extracted from the distributions of the dihedral angles. We reproduce the experimentally observed correlation between the conformational and binding entropies and quantify the thermodynamic contributions of different binding regions for a number of CaM-peptide complexes. The histograms would be sensitive to any quantity that undergoes changes upon binding. Hence, our analysis can be suitably extended to calculate thermodynamic changes in the solvent and any other macromolecular complex like protein-protein, protein-DNA, or protein-ligand complexes. The detailed thermodynamic information of the binding regions would enable us to identify the prime spots of binding, facilitating the manipulation of the macromolecules required for various applications such as drug design, drug delivery, and so forth.

Acknowledgments

A.D. thanks the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India for a research Fellowship.

Contributor Information

J. Chakrabarti, Email: jaydeb@bose.res.in.

Mahua Ghosh, Email: mahuaghosh@bose.res.in.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Dudev T., Lim C. Metal binding affinity and selectivity in metalloproteins: insights from computational studies. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:97–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jayaram B., McConnell K.J., Beveridge D.L. Free energy analysis of protein-DNA binding: the EcoRI endonuclease-DNA complex. J. Comput. Phys. 1999;151:333–357. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh M., Meiss G., Pedersen L.C. The nuclease a-inhibitor complex is characterized by a novel metal ion bridge. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:5682–5690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605986200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wereszczynski J., McCammon J.A. Statistical mechanics and molecular dynamics in evaluating thermodynamic properties of biomolecular recognition. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2012;45:1–25. doi: 10.1017/S0033583511000096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jorgensen W.L. Drug discovery: pulled from a protein’s embrace. Nature. 2010;466:42–43. doi: 10.1038/466042a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brokx R.D., Lopez M.M., Makhatadze G.I. Energetics of target peptide binding by calmodulin reveals different modes of binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:14083–14091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akke M., Bruschweiler R., Palmer A.G. NMR order parameters and free energy: an analytical approach and its application to cooperative Ca2+ binding by calbindin D9k. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:9832–9833. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang D., Kay L.E. Contributions to conformational entropy arising from bond vector fluctuations measured from NMR-derived order parameters: application to protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;263:369–382. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z., Raychaudhuri S., Wand A.J. Insights into the local residual entropy of proteins provided by NMR relaxation. Protein Sci. 1996;5:2647–2650. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Igumenova T.I., Frederick K.K., Wand A.J. Characterization of the fast dynamics of protein amino acid side chains using NMR relaxation in solution. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:1672–1699. doi: 10.1021/cr040422h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meirovitch H. Recent developments in methodologies for calculating the entropy and free energy of biological systems by computer simulation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007;17:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prompers J.J., Bruschweiler R. Thermodynamic interpretation of NMR relaxation parameters in proteins in the presence of motional correlations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:11416–11424. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schafer H., Mark A.E., van Gunsteren W.F. Absolute entropies from molecular dynamics simulation trajectories. J. Chem. Phys. 2000;113:7809–7817. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baron R., Hünenberger P.H., McCammon J.A. Absolute single-molecule entropies from quasi-harmonic analysis of microsecond molecular dynamics: correction terms and convergence properties. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009;5:3150–3160. doi: 10.1021/ct900373z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suarez E., Díaz N., Suarez D. Entropy calculations of single molecules by combining the rigid rotor and harmonic-oscillator approximations with conformational entropy estimations from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:2638–2653. doi: 10.1021/ct200216n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks B., Karplus M. Harmonic dynamics of proteins: normal modes and fluctuations in bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:6571–6575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.21.6571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karplus M., Kushick J.N. Method for estimating the configurational entropy of macromolecules. Macromolecules. 1981;14:325–332. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gromiha M.M., Fukui K. Scoring function based approach for locating binding sites and understanding recognition mechanism of protein-DNA complexes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:721–729. doi: 10.1021/ci1003703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samanta S., Chakrabarti J., Bhattacharyya D. Changes in thermodynamic properties of DNA base pairs in protein-DNA recognition. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2010;27:429–442. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2010.10507328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang C.-E., Chen W., Gilson M.K. Evaluating the accuracy of the quasiharmonic approximation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005;1:1017–1028. doi: 10.1021/ct0500904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trbovic N., Cho J.-H., Palmer A.G., 3rd Protein side-chain dynamics and residual conformational entropy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:615–622. doi: 10.1021/ja806475k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Killian B.J., Yundenfreund Kravitz J., Gilson M.K. Extraction of configurational entropy from molecular simulations via an expansion approximation. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;127:024107. doi: 10.1063/1.2746329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendez R., Bastolla U. Torsional network model: normal modes in torsion angle space better correlate with conformation changes in proteins. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;104:228103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.228103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li D.-W., Meng D., Brüschweiler R. Short-range coherence of internal protein dynamics revealed by high-precision in silico study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:14610–14611. doi: 10.1021/ja905340s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li D.-W., Brüschweiler R. In silico relationship between configurational entropy and soft degrees of freedom in proteins and peptides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:118108. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.118108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li D.-W., Showalter S.A., Brüschweiler R. Entropy localization in proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:16036–16044. doi: 10.1021/jp109908u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DuBay K.H., Geissler P.L. Calculation of proteins’ total side-chain torsional entropy and its influence on protein-ligand interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;391:484–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frederick K.K., Marlow M.S., Wand A.J. Conformational entropy in molecular recognition by proteins. Nature. 2007;448:325–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma L., Ahmed Z., Asher S.A. UV resonance Raman measurements of poly-L-lysine’s conformational energy landscapes: dependence on perchlorate concentration and temperature. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7675–7680. doi: 10.1021/jp0703758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ytreberg F.M., Zuckerman D.M. Simple estimation of absolute free energies for biomolecules. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;124:104105. doi: 10.1063/1.2174008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cecchini M., Krivov S.V., Karplus M. Calculation of free-energy differences by confinement simulations. Application to peptide conformers. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:9728–9740. doi: 10.1021/jp9020646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park S., Lau A.Y., Roux B. Computing conformational free energy by deactivated morphing. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;129:134102. doi: 10.1063/1.2982170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spichty M., Cecchini M., Karplus M. Conformational free-energy difference of a miniprotein from nonequilibrium simulations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:1922–1926. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maragakis P., Spichty M., Karplus M. A differential fluctuation theorem. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:6168–6174. doi: 10.1021/jp077037r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhuravlev P.I., Wu S., Papoian G.A. Computing free energies of protein conformations from explicit solvent simulations. Methods. 2010;52:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babu Y.S., Sack J.S., Cook W.J. Three-dimensional structure of calmodulin. Nature. 1985;315:37–40. doi: 10.1038/315037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuboniwa H., Tjandra N., Bax A. Solution structure of calcium-free calmodulin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1995;2:768–776. doi: 10.1038/nsb0995-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang M., Tanaka T., Ikura M. Calcium-induced conformational transition revealed by the solution structure of apo calmodulin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1995;2:758–767. doi: 10.1038/nsb0995-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Neil K.T., Wolfe H.R., Jr., DeGrado W.F. Fluorescence properties of calmodulin-binding peptides reflect α-helical periodicity. Science. 1987;236:1454–1456. doi: 10.1126/science.3589665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kahl C.R., Means A.R. Regulation of cell cycle progression by calcium/calmodulin-dependent pathways. Endocr. Rev. 2003;24:719–736. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wintrode P.L., Privalov P.L. Energetics of target peptide recognition by calmodulin: a calorimetric study. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;266:1050–1062. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang M., Vogel H.J. Characterization of the calmodulin-binding domain of rat cerebellar nitric oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:981–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Osawa M., Tokumitsu H., Ikura M. A novel target recognition revealed by calmodulin in complex with Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:819–824. doi: 10.1038/12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marlow M.S., Dogan J., Wand A.J. The role of conformational entropy in molecular recognition by calmodulin. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:352–358. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gifford J.L., Ishida H., Vogel H.J. Fast methionine-based solution structure determination of calcium-calmodulin complexes. J. Biomol. NMR. 2011;50:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee A.L., Kinnear S.A., Wand A.J. Redistribution and loss of side chain entropy upon formation of a calmodulin-peptide complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:72–77. doi: 10.1038/71280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hansen J.P., McDonald I.R. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2006. Theory of Simple Liquids. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gilson M.K., Given J.A., McCammon J.A. The statistical-thermodynamic basis for computation of binding affinities: a critical review. Biophys. J. 1997;72:1047–1069. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78756-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brooks B.R., Brooks C.L., III, Karplus M. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comp. Chem. 2009;30:1545–1615. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krishnan M., Smith J.C. Reconstruction of protein side-chain conformational free energy surfaces from NMR-derived methyl axis order parameters. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:4124–4133. doi: 10.1021/jp2104853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Best R.B., Clarke J., Karplus M. What contributions to protein side-chain dynamics are probed by NMR experiments? A molecular dynamics simulation analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;349:185–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anthis N.J., Doucleff M., Clore G.M. Transient, sparsely populated compact states of apo and calcium-loaded calmodulin probed by paramagnetic relaxation enhancement: interplay of conformational selection and induced fit. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18966–18974. doi: 10.1021/ja2082813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuczera K., Kursula P. Interactions of calmodulin with death-associated protein kinase peptides: experimental and modeling studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2012;30:45–61. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2012.674221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.