Synopsis

This paper presents an introduction to economic outcomes for the plastic surgeon investigator. The types of economic outcomes are introduced and the matter of perspective is discussed. Examples from the plastic surgery literature are presented. The current and future importance of economic outcome measures is emphasized.

Keywords: Outcomes, plastic surgery, economic principles, evidence based medicine

Overview

In the 1950s and 1960s, as growing access to medical care led to concerns about increasing costs, research focus turned to the results of interventions.1,2 This new attention toward the end effects of treatment was dubbed the “outcomes movement” and was labeled the “third revolution in healthcare” by then-editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, Arnold Relman.1 Outcomes research strives to understand the results of interventions. These results are any patient experiences, including mortality, complications (or lack thereof), function, or quality of life, and can be reported by the provider, the patient, or by a third party.3 As the movement spread, reporting of outcome became almost cursory. The increased prominence of outcomes led to what some call the fourth revolution in healthcare – evidence-based medicine (EBM).4 EBM seeks to analyze and compare the outcomes, benefits and risks of medical treatments, drugs and devices to guide decision-making by healthcare providers, consumers and payers.5 This is hoped to reduce rapidly growing healthcare spending thought to be caused, partially, by the lack of evidence for the effectiveness of many costly, innovative treatments.6 Lack of evidence is not limited to new innovations, however, 85% of common medical treatments have not been rigorously validated.7

In today’s healthcare marketplace, economic outcomes are increasingly becoming part the assessment of medical interventions. Economic outcomes are indeed outcomes because they are a results of a care encounter,8 although they are not typically considered as such. The rate at which new surgical technique are introduced in plastic surgery make the field especially conducive to the analysis of economic outcomes.9 However, a systematic review of plastic surgery outcomes research from 1998 to 2004 found that only 3% of studies reported economic outcomes.10 Possible reasons for this include unfamiliarity of plastic surgeon investigators with economic outcomes and that for some procedures the costs are borne by patients.9,11 To maintain an position of impact on healthcare policy, plastic surgeons need to include economic outcomes in their research whenever feasible.10 The aim of this paper is to inform plastic surgeon investigators on the basics of economic outcomes and provide examples of their use in the plastic surgery literature.

What are economic outcomes?

The most simple economic outcome is cost, the actual value of the resources consumed or depleted while providing a service.11–13 Costs can be divides into several categories. Direct costs are generally the items one first thinks of when considering costs: supplies, medication, and personnel.11,13 Fixed direct costs are those that remain the same regardless of the number of time the service is provided.11,13 These items, such as facilities, administrative costs, and durable equipment, cost roughly the same amount to own irrespective of frequency of use. Variable costs, likewise, are reliant on the number of times a service is provided. For instance, labor is largely dependent on the availability of work.11,13 Combined with direct costs are indirect costs. These costs are more difficult to quantify and include items like loss wages due to time off of work or decreased work ability.11,13 Even more difficult, or nearly impossible, to calculate are intangible costs, a monetary representation of non-financial outcomes such as pain, suffering, even negative effects on relationships.11,13 The final item in the calculation of total costs is opportunity costs. These costs represent the loss value when resources cannot be used in another manner. For instance, if an operating room is being used for a procedure that brings a hospital little income, it cannot be used for a more lucrative procedure.14 This may be less of an issue for plastic surgery, because the specialty’s hypothetical opportunity costs are low when compared to other surgical specialties.14 To get a complete picture of costs it is important to include all elements.

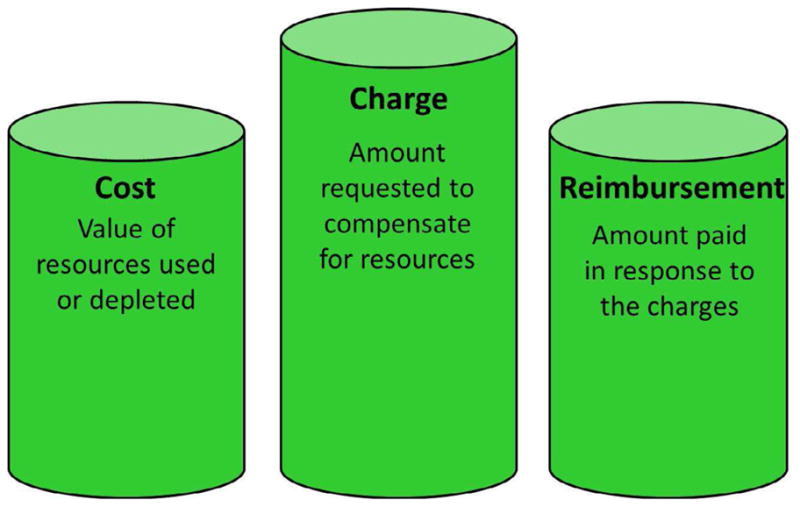

Costs are not the only economic outcome. Charges may also be the outcome of interest. Charges are how much is billed for a service, which may not reflect the actual cost.12,13 Reimbursement, the amount received for in exchange for a service, can be used as an outcome as well. In general, charges are higher than costs, owing to inclusion of profit and protection against uncompensated costs.11–13 Reimbursements vary from $0 to the full amount charged and may be set by a third party, as in the case of Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reimbursement rates.11 The tenuous relationship between these 3 economic outcome measures means that they are not interchangeable. (Figure 1) It is important to know what one is being used when a study is assessed. Likewise when performing a study it is equally important to specify which outcome is being used.

Figure 1.

The relationship between costs, charges, and reimbursements.

Whose Perspective?

When using traditional outcomes measures, it is easy for all parties to come to consensus on what constitutes a good outcome. Patients, providers, and third-party payers can all agree that reduced pain is positive. But matters of finances are less clear. Whereas patients may experience better aesthetic outcomes following more expensive intervention, if the provider is not recouping costs, it is not universally favorable.9 Therefore, it is important for researchers to be explicit about who is benefitting from the intervention under investigation.9 This is important information for readers of published studies because only studies performed from the same perspective can be compared.12

The perspective taken depends upon the research question being asked; there is no standard “best” perspective. Due to the public nature of CMS reimbursement rates, assessing outcomes from a CMS perspective is relatively simple. Because other third-party payers base reimbursement rate on CMS rates, these figures can be extrapolated to third-party payers as a whole. With many plastic surgeons operating private practices, examining economic outcomes from the provider perspective can be enlightening including specific outcomes, such as revenue (the amount earned) or profit (the amount earned after operating costs are subtracted). In the last decade, however, there has been a shift toward patient-rated outcomes, thus there has been an increased interest in the economic ramifications of interventions on patients.15 This is in line with movements to empower patients and encourage their active role in healthcare.16 The patient perspective can be difficult to generalize. For procedures that are covered by third-party payers, patient costs can be negligible, placing more emphasis on indirect costs such as travel costs or loss wages, which are highly variable. The patient perspective is also most likely of all perspectives to include intangible costs as well, which are nearly impossible to quantify. The societal perspective takes into account everyone who is impacted by an intervention, including individuals who are generally not considered, such as tax payers or coworkers who must work extra hours to cover for an ill employee.12 But including all these viewpoints can be exceedingly difficult; to truly represent the perspective of society, members of the general public should provide values.17

Ideally, all costs that result from an encounter should be tallied, includes cost-savings if an intervention avoid a more expensive outcome and difficult to calculate indirect, intangible and opportunity costs.8 But to include every item is impossible. For this reason, economic analyses are often based on variety of assumptions, including estimated costs. Costs can be varied over a range of values to determine the robustness of the estimates to draw conclusions despite difficulty calculating exact costs.12

Examples in plastic surgery literature

Provider perspective

When considering the provider perspective, whether individual surgeon, practice, or institutional, it is important to consider operating costs in addition to revenue. Given the perceived low reimbursement rates for postmastectomy breast reconstruction, Alderman et al., wished to assess the impact of a variety of procedures on an academic plastic surgery practice and on the institution as a whole. Practice costs included physician salary, benefits, CME, malpractice insurance, and taxes, whereas institution costs were composed of fixed costs such as facility costs and variable costs such as nurse salaries and the costs of anesthesia. Also included were indirect costs such as administrators’ salaries. Revenue was in the form of reimbursements, and profit was calculated by subtracting costs from revenue. This analysis illustrates the importance of distinguishing between charges and reimbursements. For both the institution and the practice, reimbursements were markedly less than charges. The institution received 56% of the amount billed, whereas the practice received only 32%.18 Despite this, overall an academic plastic surgery practice collects a profit of 27% for breast reconstruction, whereas the institution collects a 15% profit. To compare procedures, the authors calculated reimbursements by amount of time spent in the OR. Delayed tissue expander plus implant reconstruction brought in the highest reimbursement/OR hour, more than 5 times more than immediate transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap reconstruction, which was reimbursed a the lowest rate.18

Alderman et al., bring to light the issue of perspective, countering low physician and instruction reimbursement with evidence that patients prefer the aesthetic outcomes following TRAM flaps.18 Situations such as this are likely to only grow in number as our healthcare system attempts to balance financial constraints with an engaged public.

Third-party payer perspective versus patient perspective

Minimally invasive procedures may cost less, may require less operating room time, often fewer staff, and generally shorter hospital stays. For these reasons, minimally invasive procedures are generally preferred by payers and patients alike. But when hospital stays are shortened, there is often more home care involved and these costs may add up as well. Abbott et al., compared the costs to third-party payers as well as non-covered patient costs associated with two treatments for sagittal synostosis: cranial vault remodeling, which is more invasive and requires a long hospital stay, and endoscopically assisted suturectomy, which is associated with shorter hospital stays, but requires the use of an orthotic device and numerous outpatient visits.19 Third-party payer costs included both hospital and physician costs. Hospital costs included costs that could be directly attributed to patients, such as supplies and medication. Overhead costs, like building maintenance and administration, that cannot be attributed to a single patient were included using a formula estimates the proportion of these items used. Physician costs were calculated on a departmental basis by determining a cost-to-charge ratio each speciality involved.19 Non-covered patient costs were indirect costs incurred by patients (or in this case patients’ families) including wages loss for hospitalization and follow-up visits, gas and auto wear and tear associated with driving to the hospital and to appointments. These are, of course, estimates based on patient populations as a whole; naturally, individually costs vary widely.

The authors found that cranial vault remodeling costs almost twice as much as endoscopically assisted suturectomy ($55,121 versus $23,377).19 However, the costs to patients were significantly more following endoscopically assisted suturectomy than following cranial vault remodeling ($3088 versus $2835, p<0.001), owing primarily to cost associated with outpatient follow-up visits.19 This highlights the importance of considering the costs to all parties involved. Treatment that is less costly to the healthcare system may increase costs to individuals. Although the cost difference to patient is minimal in this example, in some cases it may render the “cheaper” option unaffordable.

Beyond Economic Outcomes – Including other types of outcomes

The practice of medicine is primarily about improving the lives of patients, not about saving money. Examples like the previous one often lead to questions about more than costs: Which procedure has better outcomes? Which do patients and their families prefer? These questions require a more in-depth analysis combining economic and other types of outcomes. In such an analysis costs are considered along with outcomes to answer the question, “Are the outcomes worth the resources consumed?”20

Detailed instruction on the performance of an economic analysis has been published previously in this journal and is beyond the scope our discussion.9 Briefly, there are four broad categories of economic analyses: cost-minimization, cost-effectiveness, cost-utility, and cost-benefit.9,12 Unique to plastic surgery, outcomes tend more toward patient satisfaction or improved quality of life than toward mortality or life-years gained.11 This makes cost-utility analyses ideal for the plastic surgery setting. Utility is the preference that one places on a particular health state, measured on a scale from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). Utilities can be elicited from a variety of populations, including patients, providers, and the general public, depending upon the perspective sought. As with costs, it is important to remember that utilities can only be compared if they are obtained from the same perspective.21–23 Utility values can be combined with the time spent in a health state to produce quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), a method to place value on time spent in a disabled state.20 This also allows the calculation of cost/QALY gained. Although the US government does not allow the use of QALYs to create payment thresholds,24 a threshold of $50,000 to $150,000 is generally considered acceptable in most research settings.25

Example in plastic surgery literature

Open fracture of the lower leg is devastating. Amputation and salvage are the two treatment options and regardless of which is pursued, recovery is long and often fraught with complications. Chung et al., examined the 2 year and lifetime costs of amputation and salvage, as well as preference for these treatments. Costs were from the third-party payer perspective and included initial hospitalization, inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation, outpatient doctor visits, and the purchase and maintenance of prosthetics.26 To better estimate lifetime costs, dollar amounts were adjusted for inflation and for the discounted value of money over time.26 Utility was elicited from reconstructive surgeons and physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians using an online survey.

Salvage was the less costly intervention both initially and over a patient’s lifetime.26 Salvage was also more preferred by providers, making it the dominate treatment option. Had amputation been the less costly intervention, further calculations involving QALYs could have determined if the cost savings were “worth it” in the opinion of providers. It is possible that the increased quality of life following salvage may be outweighed by the cost-savings of using amputation.

Bottom Line

Plastic surgery is a field that benefits from an influx of new innovations. Unfortunately, those innovations are frequently more expensive than those that came before them. This underscores the importance of incorporating economic outcomes in plastic surgery research as part of the best available evidence to support the adoption or rejection of interventions. This is complicated, however, by the matter of perspective. Whereas patient, providers, and third-party payers can see eye-to-eye on a number of issues, the inclusion of finances has a way of making matters thornier. The combination of economic outcomes with quality of life data can be an especially powerful tool for balancing competing priorities.9

Currently many analyses focus on the physician perspective, either at the practice or institutional level. But as debate as to who is responsible to pay for healthcare (i.e. private citizens versus the government) continues, interest will be drawn to the patient perspective and to the societal costs of interventions. The current healthcare climate is that of scarce funding. Although it is comforting to believe that healthcare exists in a vacuum where the cost of care and who is paying is not relevant, economic outcomes simply have to be in the conversation.

Key Points.

Economic outcomes are gaining stature as healthcare funding dwindles

The complex mix of payer in the specialty of plastic surgery makes collecting economic outcomes more difficult, but more important

When creating or assessing an analysis including economic outcomes, it is essential that the perspective is clearly stated

In order to maintain a position of national policy relevance, plastic surgeons must include economic outcomes in analyses

In today’s healthcare climate of scarcity of funding it is prudent to include economic outcomes in competitive effective research whenever feasible.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Aging and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01 AR062066) and from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (2R01 AR047328-06) and a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AR053120) (to Dr. Kevin C. Chung).

Abbreviations: Applying Economic Principles to Outcomes Analysis

- CMS

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- QALYs

quality-adjusted life years

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Relman AS. Assessment and accountability: the third revolution in medical care. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1220–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811033191810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung KC, Burns PB, Davis Sears E. Outcomes research in hand surgery: where have we been and where should we go? J Hand Surg. 2006;31A:1373–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Outcomes research fact sheet. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung KC, Ram AN. Evidence-based medicine: the fourth revolution in American medicine? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:389–98. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181934742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.What is comparative effectiveness research? Agency for Health Care Research and Quality; US Department of Health and Human Services; [Accessed March 21, 2012]. at http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/index.cfm/what-is-comparative-effectiveness-research1/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pear R. The New York Times 2009. Feb 16, 2009. US to Compare Medical Treatments. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kocher MS, Henley MB. It is money that matters: decision analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003:106–16. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000079326.41006.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan JM. Understanding economic outcomes in critical care. Curr Opin Critical C. 2006;12:399–404. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000244117.08753.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thoma A, Strumas N, Rockwell G, McKnight L. The use of cost-effectiveness analysis in plastic surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 2008:285–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis Sears E, Burns PB, Chung KC. The outcomes of outcome studies in plastic surgery: a systematic review of 17 years of plastic surgery research. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:2059–65. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000287385.91868.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kezirian EJ, Yueh B. Introduction of cost analysis in facial plastic surgery. Facial Plast Surg. 2002;18:95–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotsis SV, Chung KC. Fundamental principles of conducting a surgery economic analysis study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:727–35. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181c91501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiba N, Gralnek IM, Moayyedi P, et al. A glossary of economic terms. Eur J Gastr Hep. 2004;16:563–5. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200406000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatterjee A, Payette MJ, Demas CP, Finlayson SRG. Opportunity cost: a systemtic application to surgery. Surgery. 2009;146:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bindra RR, Dias JJ, Heras-Palau C, Amadio PC, Chung KC, Burke FD. Assessing outcome after hand surgery: the current state. J Hand Surg. 2003;28B:289–94. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(03)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alderman AK, Chung KC. Measuring outcomes in hand surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 2008;35:239–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wimo A. Clinical and economic outcomes - friend of foe? Int Psychogeriatrics. 2007;19:497–507. doi: 10.1017/S1041610207004930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alderman AK, Storey AF, Nair NS, Chung KC. Financial impact of breast reconstruction on an academic surgocal practice. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1408–13. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a0722d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abbott MM, Rogers GF, Proctor MR, Busa K, Meara JG. Cost of treating sagittal synostosis in the first year of life. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:88–93. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318240f965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drummond MF, Richardson WS, O’Brien BJ, Levine M, Heyland D. Users’ guides to the medical literature. XIII. How to use an article on economic analysis of clinical practice. A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1997;277:1552–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.19.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnold D, Girling A, Stevens A, Lilford R. Comparison of direct and indirect methods of estimating health state utilities for resource allocation: review and empirical analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2688. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLernon DJ, Dillon J, Donnan PT. Health-state utilities in liver disease: a systematic review. Med Decis Making. 2008;28:582–92. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08315240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mortimer D, Segal L. Comparing the incomparable? A systematic review of competing techniques for converting descriptive measures of health status into QALY-weights. Med Decis Making. 2008;28:66–89. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07309642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. HR 3590 - 111th Congress; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudolph SH, Levine SR. Telestroke, QALYs, and current health care policy: the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. Neurology. 2011;77:1584–5. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823433aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung KC, Saddawi-Konefka D, Haase SC, Kaul G. A cost-utility analysis of amputation versus salvage for Gustilo type IIIB and IIIC open tibial fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1965–73. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181bcf156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]