Synopsis

Evidence based medicine is analyzed from its inception. The authors take the reader through the early formation of ‘scientific medicine’ that has evolved into the multi-purpose tool it has become today. Early proponents and their intentions that sparked evidence base and outcomes are presented: the work of David Sackett, Brian Haynes, Peter Tugwell, and Victor Neufeld is discussed - how they perceived the need for better clinical outcomes that led to a more formalized evidence based practice. The fundamentals are discussed objectively in detail and potential flaws are presented that guide the reader to deeper comprehension.

Keywords: Evidence-based medicine, Outcomes

OVERVIEW

While counseling his students over 2500 years ago, Hippocrates declared that the physician need to “rely on actual evidence rather than on conclusions resulting solely from reasoning, because arguments in the form of idle words are erroneous and can be easily refuted.”1 Since the early days of medicine, there has been a need for evidence-based inquiries that enable a physician to ascertain and apply the best treatment strategy for each patient. Even during the early era of medicine, physicians understood the importance of using evidence to guide treatment protocols. Although we identify the outcomes movement and evidence based medicine (EBM) as new terms, the ideas that embody these themes are as old as organized medicine itself. Increased government involvement combined with exceedingly detailed and intense patient demands have made the modern outcomes movement and EBM an essential component of research and clinical practice.

Early evidence-based medicine movement

The outcomes movement and EBM were spurred on by many early proponents, some of whom were shunned by their peers in response to the radical new ideas which they imposed. During the 1800s, the celebrated nurse Florence Nightingale used evidence gained from careful record keeping, observation, and statistical measurements to foster health care reform, becoming one of the earliest supporters of EBM.2 Ernest Codman advocated meticulous data collection, patient follow-up, and the analysis and interpretation of patient outcomes to improve care and treatment methods. Although his ideas had practical value, his peers did not share his enthusiasm for the improvement of outcomes, instead preferring to alienate the brilliant surgeon and continue using the dated techniques and treatment methods that they had learned during their medical training.3,4 Archie Cochrane championed the use of rigorously performed randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews, sparking the interest of those who would go on to place them at the top of the research hierarchy.5 Although they did not articulate these efforts in a particular terminology, these early pioneers were instrumental to the implementation of outcomes research and EBM into the field of medicine.

Modern evidence-based medicine movement

The modern outcomes movement in the United States has its roots in the Era of Expansion of the 1950s and 60s that stimulated a massive overhaul of the medical industry. This period was distinguished by a substantial increase in the number of medical facilities and physicians, extraordinary advances in science and medical technology, and for the first time an augmentation of medical insurance coverage into the majority of U.S. households. These changes created a different hospital system, attracting private investors who were looking to increase profit margins. The increased demand for medical services coupled with the high expenses incurred from sophisticated medical technology led to a substantial increase in medical costs. The soaring cost of medical care caused a crisis where patients began to demand lower prices for medical services. Also feeling the burden of high costs, the federal government and employers followed suit and started dictating the costs of health care, paying the hospitals much less than they were charging for the services that were being provided.

At the same time, the American public began to question the quality of the new, high tech, and expensive treatment protocols that were quickly becoming standard practice. The Era of Expansion initially generated a belief that by increasing hospital admittance rates the overall population would be healthier, a belief that was later found invalid. Several investigators have documented the variations in healthcare among different regions and hospitals, and soon established that high admittance rates and medical costs do not always translate to better medical care and a healthier population.6–11 These studies also raised concerns over the impact these substantial variations in health care might have on a population.12–16 Areas with easy access to health care and high admittance rates may have increased rates of unnecessary procedures, which could result in higher rates of preventable complications and increased medical costs. Populations in areas with low admittance rates may experience difficulty obtaining access to care and may not benefit from the advances of modern medicine. Due to the high variability of medical and surgical services among practitioners, hospitals, and regions, the optimal rate of hospital admittance and surgical interventions for different patients and conditions remains to be determined. This research avenue demands continued exploration so that we can contain costs and simultaneously improve healthcare among all populations.

Evidence-based strategies momentum in the medical community

Although the outcomes movement gathered considerable momentum in the medical research sector, its application has not halted the continued escalation of healthcare costs and the uncertain quality of medical services. Even so, the outcomes movement has played an important role in paving the way for the widespread implementation and acceptance of evidence-based strategies into the medical community. In fact, EBM was specifically designed to address the shortcomings that are apparent in the outcomes movement by focusing simply on the application of outcomes data rather than the scientific rigor of deriving these outcomes data. Physicians David Sackett and Gordon Guyatt would lay the initial groundwork for the development of EBM, and both would go on to provide substantial contributions to the continued evolution of the concept.

While studying ways to improve treatment compliance of hypertension in 1975, Dr. David Sackett discovered a disturbing trend. He and the other investigators found that a determining factor in the prescribing treatment for hypertension was the graduating year of the physician. It appeared that the treating physicians were basing their management of patients on the treatment protocol that was considered acceptable at the time they had completed their medical training, even if the treatment was completely outdated.17 This recurring theme prompted David Sackett, Brian Haynes, Peter Tugwell, and Victor Neufeld to publish a series of articles beginning in 1981 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal highlighting the importance of a physician’s ability to carefully read and comprehend research published in medical journals.18 In this series of articles, the authors emphasize using epidemiology concepts to apply the best available evidence and solve clinical problems. These articles were aimed at helping the busy clinician stay up-to-date with the latest advances in medicine.

The phrase “evidence based medicine” was initially coined in 1990 by Dr. Gordon Guyatt, after an unsuccessful attempt to implement a new strategy he originally defined “Scientific Medicine” into an internal medicine residency program at McMasters University. His “Scientific Medicine” program was designed to enhance clinical treatment with the application of current systematic scientific evidence, modeled after the ideas of his mentor David Sackett. The program was promptly disparaged by his peers who were offended at the implication that current decision-making practices in medicine lacked scientific qualities.19 This persuaded Dr. Guyatt to issue his initiative a new designation: evidence based medicine. With this new name his proposed residency program curriculum was well received, compelling Guyatt to officially publish the term in a 1991 editorial.20 Not long after, a team at McMasters University, including Sackett and Guyatt, continued improving upon the idea of EBM, eventually leading to an international collaboration between Canadian and American academicians to further enhance this novel approach to medicine.

International evidence-based medicine working group

The International EBM Working Group, as it became known, worked to further refine EBM from Sackett’s original critical appraisal articles and Guyatt’s previous concepts. They discovered that, although the critical appraisal articles were helpful in guiding clinicians to better understand the quality of evidence in scientific articles, they lacked instruction on applying the evidence gained from scientific studies to the clinical setting. After addressing potential problems and enhancing the existing components of EBM, an improved version was officially introduced in 1992, promoting the critical appraisal, identification, and application of evidence.21 This was followed by the JAMA User’s Guide to the Medical Literature, a publication initially designed to help physicians better understand the basic concepts of evidence based medicine, and later progressing into a series of 25 articles as the initiative evolved and gained acceptance.

Evidence based medicine bridges the gap between research and practice

At its core, evidence based medicine attempts to bridge the gap between the realms of research and practice. Although seemingly simple, this ideal is exceedingly complicated, plagued by countless arguments concerning effectiveness, a lack of procedural and technical comprehension, a pervasive fear of abuse, and an overabundance of poorly performed studies that hamper the use and quality of data. To account for these challenges and address the opposition to EBM, Sackett et al. published a short explanation titled Evidence Based Medicine: What it is and what it isn’t that highlights the implications and importance of such a system.22 The authors also explain that a good clinician must rely on individual experience and expertise, and incorporate the best available evidence to achieve the best possible outcomes, but that neither of these elements is sufficient in and of itself to provide the best care. Clinical experience is vital, but can quickly become outdated without the support of a good scientific knowledge-base, whereas evidence alone can result in the poor management of a patient when the data are not applied appropriately based on specific patient characteristics and needs. Thus, it is essential that physicians use both clinical experience and the best available evidence to provide the best treatment, a concept that has now been established as a fundamental principle for evidence based practices.

Fundamental principles of evidence based medicine

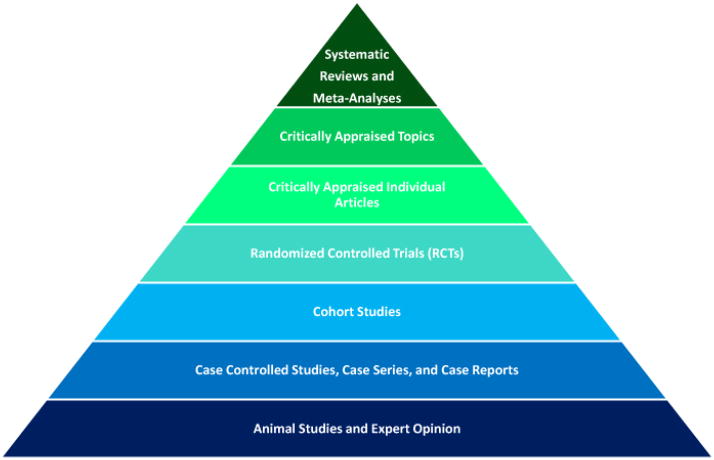

In its current state, the User’s Guide to the Medical Literature highlights not only the appraisal and application of the best available evidence, but also the importance of patient preferences and values in terms of evidence based medicine (Figure 1).23 The second fundamental principle of EBM is just as important as the first rule of collecting and analyzing evidence, and entails that “clinical decisions, recommendations, and practice guidelines must not only attend to the best available evidence, but also to the values and preferences of the informed patient.”24 Despite this property of EBM and its overall prevalence, there is a gap between evidence based medicine and preference based medicine, and as more emphasis is put on patient-centered research and treatment, this gap must be narrowed in order to effectively satisfy patient wants and needs. In 2001, the Institute of Medicine asserted that patient-centered medical care based on the highest level of evidence is a critical aspect of high quality health care.25 It is far too often the case that clinicians and academicians forget or overlook this fundamental ideal of evidence based medicine, but its importance cannot be overstated, especially to the patients who feel the direct effects of medical decisions.

Figure 1.

Evidence based medicine is composed of three main components, the best available evidence, patient preferences and values, and clinical experience and expertise. These three elements must be used concurrently in order to successfully implement the concept of EBM into clinical practice.

One of the primary roles of the clinician is to provide each patient with essential background information about the patient’s condition, including long-term effects with and without intervention, treatment options, and outcomes of therapeutic measures, in a way that is comprehensible to the patient. It is up to the physician to keep the patient and their family adequately informed so that they are capable of making a treatment decision that is most appropriate for the patient, based on the best available evidence as well as the patient’s goals and values. It is not the job of a physician to push a specific treatment on the patient, but to enable the patient to make their own informed decision. As in EBM, there are biases involved during decision-making for the patient, and care must be taken to limit these influences. If the patient is optimistic about a treatment or their potential involvement in a study, the physician must be careful to avoid selection bias by providing accurate information about the associated morbidity, risks, and complications of a particular regimen or procedure. A pessimistic patient must also be presented with accurate information about a treatment, but not in a way that would persuade them to accept the treatment. The physician must remember that, aside from emergency situations, they should only make recommendations, and it is the patient’s decision of what treatment, if any, is to be used.

The paucity of randomized controlled trials in plastic surgery and the inability to perform some of these studies has left the field lacking level 1 evidence for many treatment options. It is quite apparent that this lack of evidence calls for an increase in the amount of research performed in the field of plastic surgery, but also that the evidence gained from this research must be appropriately applied to each individual patient’s wants and needs. The surgical specialty has features that make it difficult to perform RCTs because a very specific set of expertise and systems is required to produce successful treatment results, but this does not mean it cannot be done. In the instance where a surgical treatment is eligible for investigation with an RCT, it is imperative that the treatment be standardized so as to prevent flawed results. For example, if a study were conducted on the different surgical treatment options available for distal radius fractures, each distinct surgical intervention would have to be performed in the same way by each participating surgeon. The field of plastic surgery has encountered a particularly difficult time in fully implementing the principles and practices that guide evidence based medicine. One of the reasons it is hard to incorporate EBM into plastic surgery is that it is not always possible to evaluate the outcomes of a profession that partially relies on artistic creativity. It is clear, however, that plastic surgeons can utilize EBM in many ways, such as overcoming the excitement of using a novel surgical technique or new medical equipment before there are sufficient data to support their use.

Flaws of evidence based medicine

Evidence based medicine is an invaluable asset in the pursuit of superior approaches to patient-centered care, but it has flaws. A common argument against evidence based medicine is that it relies too heavily on the RCT as the best available evidence. Renowned physician and epidemiologist Alvan Feinstein argued that EBM has the potential for major abuse, largely due to the fact that the RCT is the foundation for the best available evidence. He stated that RCTs omit many clinical details that are essential in decision making, including “responses to previous therapeutic agents, short-term (24 hour) response to remedial therapy, ease of regulation when the dose must be “titrated,” difficulty in compliance with therapy and reasons for noncompliance, psychic or nonclinical reasons for impaired functional status, the “social support” system available at home and elsewhere, the patient’s expectations and desires for therapeutic accomplishment, and the patient’s psychologic state and preferences.”26 Additionally he commented that a meta-analysis may be flawed if it is based on RCTs that are low quality. This is not a new theme, as even the early proponents of the meta-analysis have voiced their concern over the substantial effect the variable quality of RCTs can have on a pooled set of data.27 Feinstein goes on to say that the studies demonstrating the effectiveness of penicillin and insulin were discovered in single study articles, and by the current standards of evidence based medicine would be overlooked if reported today due to their low level on the research hierarchy. A poor quality study might lead to a type 1 or type 2 error, further complicating the study results.27 It is also apparent that there is not an effective, standardized way to assess RCT quality, and therefore evidence must be carefully measured.28 One review found that half of the studies involving a particular topic did not fulfill the basic methodological standards for a high quality study.29

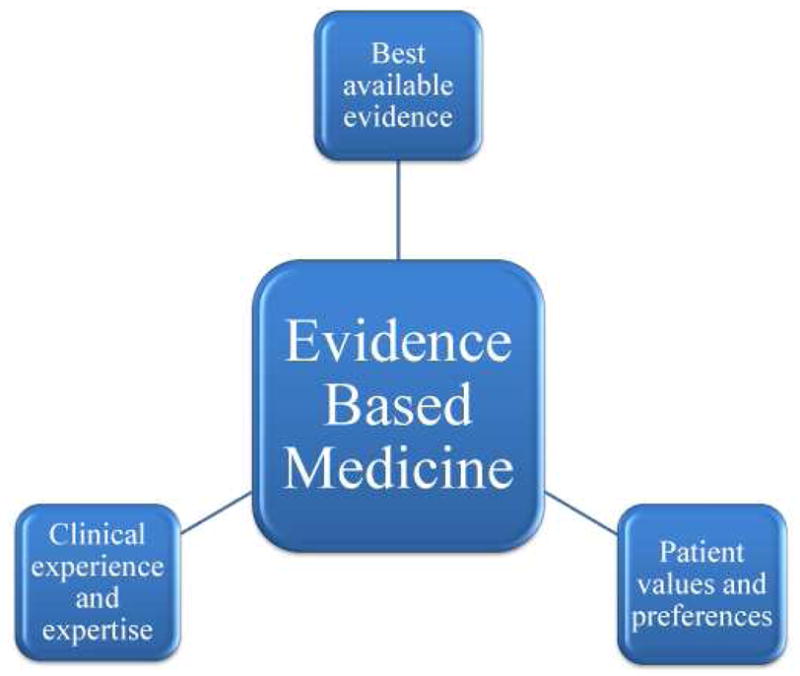

There are other problems inherent with EBM, including the emphasis it places on hierarchies (Figure 2). This dependency might inadvertently influence physicians to make decisions based on underpowered or flawed RCTs and overlook a high quality observational study due to its lower rank in the hierarchy. If EBM is to drive guidelines, it needs to be augmented with rigorously performed and methodologically sound studies that would make it a more valid source of information for decision makers and physicians. Due to the central role of the RCT to evidence based medicine, many of the problems with EBM can be avoided at this stage of the system. One common problem involves the substantial variation in the results of many RCTs, including the fact that these studies often provide contradictory results. Observational studies are known to be applicable in many areas, and Concato et al. found that there was less variability in the results of these studies when compared to RCTs on the same topic.30 A study on the effectiveness of screening mammography documented that observational studies and RCTs yield similar estimates of efficacy, and that the case-control study is a valid source of evidence when the RCT is not feasible to perform.31 Additionally, observational studies can produce similar results as RCTs when using the same criteria in the selection of study subjects. In fact, one study found that between RCTs and observational studies, one does not provide a consistently better effect than the other.32

Figure 2.

The research hierarchy was originally designed to rank the various research methods so that it would be easier for the physician to translate the most relevant and valid data into the clinical setting. Although this hierarchy is a good representation of the levels of evidence for the different research methods, it should only be used as a guideline because evidence always needs to be independently evaluated before it is used to guide clinical decisions.

We must be careful how we analyze studies before they are used to guide clinical decision making policies. Physicians are becoming increasingly aware that the RCT is not the only form of valid study, and it is becoming clear that these studies must be performed in conjunction with observational studies to find the best evidence. Merkow and Ko highlight the importance of using observational studies in a recent editorial and how these types of studies may provide answers to clinical questions that the RCT is not able to ascertain.33 They looked specifically at a recent study by Giuliano et al. that established an association between survival rates and metastases detected through the immunochemical staining of sentinel lymph nodes and bone marrow specimens from early-stage breast cancer patients.34 The study was conducted to help resolve discrepancies in the variable evidence available from previously performed large retrospective studies on occult metastases treatment, recurrence, survival rates, and recommendations. Using a series of statistical analyses, the authors concluded that there is no valid clinical support of immunocytochemical examinations of bone marrow and immunohistochemical examinations of hematoxylin-eosin-negative sentinel lymph nodes for women with early-stage breast cancer. This study is a great example of a rigorously standardized prospective cohort study that provides accurate and relevant evidence in cancer research for a subject that an RCT is not equipped to investigate.

Another major problem with the randomized controlled trial is that by nature it excludes subjects in areas that are clinically relevant. RCTs often exclude complex multi-faceted cases, or patients with a comordibity that may have significant clinical importance. An RCT may also enroll a specific regulated population that is anticipated to be responsive to a particular type of treatment. In this situation, it might be difficult for a physician to use this evidence and apply it to any patient that is not part of the group included in the study. For example, a potential RCT on breast reconstructive procedures after mastectomy may need to exclude patients who had prior radiation therapy because of the potential soft tissue complications associated with implant-based reconstruction. Therefore, this exclusion criteria will not illuminate the outcomes of implant-based reconstruction for this common subset of patients who may benefit from a less extensive form of reconstructive technique. To combat the problems associated with evidence based medicine, we must educate medical professionals in the use of EBM, including what is considered credible and applicable evidence, how to properly conduct and analyze a systematic review and meta-analysis, and how to apply evidence in a relevant way to the clinical environment.

Conclusion

The current state of health care reform calls for enhanced quality and decreased costs, and evidence based medicine will be used to accomplish this goal. No matter the opinion of the individual physician on EBM, it will increasingly dictate healthcare policy in the coming years. In fact, a recent poll in the British Medical Journal selected EBM as one of the 15 greatest milestones in medicine since 1840, alongside medical advances such as antibiotics and vaccines. Additionally, the recent enacted Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act will attempt to improve medical care by implementing “activities to improve patient safety and reduce medical errors through the appropriate use of best clinical practices, evidence based medicine, and health information technology.”35 Despite its nearly universal acceptance and approval by numerous authorities, clinicians and academicians must remain diligent to prevent the abuse of EBM, because as Alvan Feinstein said, “the threat of official, corporate, or private abuse will always remain.”26 As evidence based medicine becomes a more important aspect of the medical industry, it is important that all physicians learn how to properly conduct and utilize this novel approach to improving the quality of healthcare.

Key Points.

At its core, evidence based medicine attempts to bridge the gap between the realms of research and practice.

A recent poll in the British Medical Journal selected EBM as one of the 15 greatest milestones in medicine since 1840, alongside medical advances such as antibiotics and vaccines.

Despite its nearly universal acceptance and approval by numerous authorities, clinicians and academicians must remain diligent to prevent the abuse of EBM.

Although the outcomes movement gathered considerable momentum in the medical research sector, its application has not halted the continued escalation of healthcare costs and the uncertain quality of medical services.

Physicians are increasingly aware that the randomized control trial is not the only form of valid study, and it is becoming clear that these studies must be performed in conjunction with observational studies to find the best evidence.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Aging and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01 AR062066) and from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (2R01 AR047328-06) and a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AR053120) (to Dr. Kevin C. Chung).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mountokalakis TD. Hippocrates and the Essence of Evidence Based Medicine. Hospital Chronicles. 2006;1:7–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravind M, Chung KC. Evidence-based medicine and hospital reform: tracing origins back to Florence Nightingale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:403–9. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181c2bb89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaska SC, Weinstein JN. Historical perspective. Ernest Amory Codman, 1869–1940. A pioneer of evidence-based medicine: the end result idea. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:629–33. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199803010-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greene AK, May JW., Jr Ernest Amory Codman, M.D (1869 to 1940): the influence of the End Result Idea on plastic and reconstructive surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:1606–9. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000258529.62886.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah HM, Chung KC. Archie Cochrane and his vision for evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:982–8. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b03928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chassin MR, Brook RH, Park RE, et al. Variations in the use of medical and surgical services by the Medicare population. New England Journal of Medicine. 1986;314:285–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198601303140505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wennberg J, Gittelsohn Small area variations in health care delivery. Science. 1973;182:1102–8. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4117.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stockwell H, Vayda E. Variations in surgery in Ontario. Med Care. 1979;17:390–6. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197904000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vayda E. A comparison of surgical rates in Canada and in England and Wales. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:1224–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197312062892305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roos NP, Roos LL. High and low surgical rates: risk factors for area residents. Am J Public Health. 1981;71:591–600. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.6.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Stewart AK, Koenig RJ, Birkmeyer JD, Griggs JJ. Use of radioactive iodine for thyroid cancer. JAMA. 2011;306:721–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roos NP, Roos LL., Jr Surgical rate variations: do they reflect the health or socioeconomic characteristics of the population? Med Care. 1982;20:945–58. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roos NP, Roos LL, Jr, Henteleff PD. Elective surgical rates--do high rates mean lower standards? Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in Manitoba. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:360–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197708182970705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LoGerfo JP. Variation in surgical rates: fact vs. fantasy. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:387–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197708182970711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roos NP, Henteleff PD, Roos LL., Jr A new audit prodecure applied to an old question: Is the frequency of T&A justified? Medical care. 1977;15:1–18. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197701000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lembcke PA. Measuring the quality of medical care through vital statistics based on hospital service areas; I. Comparative study of appendectomy rates. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1952;42:276–86. doi: 10.2105/ajph.42.3.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Gibson ES, et al. Randomised clinical trial of strategies for improving medication compliance in primary hypertension. Lancet. 1975;1:1205–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.How to read clinical journals: I why to read them and how to start reading them critically. Can Med Assoc J. 1981;124:555–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sur RL, Dahm P. History of evidence-based medicine. Indian J Urol. 2011;27:487–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.91438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guyatt G. Evidence-Based Medicine. ACP J Club (Ann Intern Med) 1991;114(suppl 2):A-16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268:2420–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490170092032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ (Clinical research ed ) 1996;312:71–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, et al. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: XXV. Evidence-based medicine: principles for applying the Users’ Guides to patient care. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1290–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.10.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montori VM, Guyatt GH. Progress in evidence-based medicine. JAMA. 2008;300:1814–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America IoM. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feinstein AR, Horwitz RI. Problems in the “evidence” of “evidence-based medicine”. Am J Med. 1997;103:529–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Detsky AS, Naylor CD, O’Rourke K, McGeer AJ, L’Abbe KA. Incorporating variations in the quality of individual randomized trials into meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:255–65. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moher D, Jadad AR, Nichol G, Penman M, Tugwell P, Walsh S. Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials: an annotated bibliography of scales and checklists. Control Clin Trials. 1995;16:62–73. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(94)00031-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid MC, Lachs MS, Feinstein AR. Use of methodological standards in diagnostic test research. Getting better but still not good. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;274:645–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1887–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demissie K, Mills OF, Rhoads GG. Empirical comparison of the results of randomized controlled trials and case-control studies in evaluating the effectiveness of screening mammography. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKee M, Britton A, Black N, McPherson K, Sanderson C, Bain C. Methods in health services research. Interpreting the evidence: choosing between randomised and non-randomised studies. BMJ. 1999;319:312–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7205.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merkow RP, Ko CY. Evidence-based medicine in surgery: the importance of both experimental and observational study designs. JAMA. 2011;306:436–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giuliano AE, Hawes D, Ballman KV, et al. Association of occult metastases in sentinel lymph nodes and bone marrow with survival among women with early-stage invasive breast cancer. JAMA. 2011;306:385–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 2009. pp. 1–2409. [Google Scholar]