Abstract

Objective. To develop a consensus definition for “advocacy for the profession of pharmacy” and core competencies for doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) graduates to be effective advocates for the profession.

Methods. A 3-round modified Delphi process was conducted using a panel of 9 experts. Participants revised a definition for “advocacy for the profession” and ultimately rated their agreement using a 5-point Likert scale. Competency statements were developed and subsequently rated for importance for being an advocate and importance to address in PharmD curricula.

Results. A consensus-derived definition was developed. Two competency statements achieved consensus for both measures of importance. Four competency statements achieved consensus for only 1 measure and another 4 did not reach consensus for either measure.

Conclusion. A consensus-derived definition was developed describing advocacy for the profession of pharmacy and began laying the groundwork for the knowledge and skills necessary to be an effective advocate for the profession of pharmacy.

Keywords: advocacy, competencies, Delphi, pharmacy

INTRODUCTION

The pharmacy profession has repeatedly summoned itself to advocate for an expanded role in today’s changing health care system. These calls to action are not unique to pharmacy and can be seen in the literature of other health professions, including nursing,1-8 medicine,9-11 dietetics,12 and public health.13,14 Although it is imperative to encourage practicing pharmacists to engage in advocating for the profession, attention must also be directed to incorporating advocacy preparation in pharmacy school curricula. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) standards include several leadership-related emphases but do not specifically comment on incorporating advocacy knowledge and/or skills into pharmacy curricula.15 Since ACPE standards were released in 2007, authors of a white paper for the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Curricular Change Summit16 proposed that curricula of the future foster the development of 5 required abilities in student pharmacists, including “leadership and advocacy.” The authors emphasize that student pharmacists must develop the skills and desire to create positive change in practice and that programmatic outcomes guiding curricula should include the development of such traits.

Advocacy-related instruction is not without its challenges.1,9,11 In a qualitative study17 comparing baccalaureate nursing students’ political competence with that of political science students, nursing students clearly identified their advocacy activities as health promotion, disease prevention, and “improvement of the human condition,” but did not describe their activities as political in nature or intent. Rather, the study participants saw politics as “something other people do” and viewed policy as a barrier to practice rather than a way to facilitate change and empower themselves and others. Even though this was a single group of nursing students, similar comments can likely be heard from many health professionals, including student pharmacists, as their inherent interests are generally rooted in health-related topics rather than policy.

Another challenge comes from confusion around terminology. The textbook definition of the term advocacy is “the act of pleading or arguing in favor of something, such as a cause, idea or policy; active support.”18 Although this definition may seem simple and clear, complexities arise when determining what it is that one is advocating for and for whom. In the health literature, there have been reports on the importance of advocacy for social,11 economic, educational, legislative/political,9,19 policy/public opinion,1,13 and organizational changes.20 Additionally, the audience that is directly impacted by these suggested changes can also vary, for example, overall population health,9,11,13,20 individual patients,2,9,11 programs, and specific interest groups.19 Although the applications of advocacy are broad, as noted above, some student pharmacists may assume that advocacy requires legislative involvement. This assumption may contribute to aversion to participating in advocacy initiatives and training.

Previous reports in the pharmacy education literature about advocacy-related assignments and elective courses have acknowledged that there is little information and direction available regarding incorporating advocacy into pharmacy curricula.21-23 Similar reports of attempts to provide advocacy instruction can be found in the literature of other health professions.1,5,8,10,12,13 While these reports provide good examples of institution-specific initiatives, there is still a lack of consensus regarding the specific goals and desired outcomes of instruction. Some examples of competencies for advocacy instruction exist in the health professions literature. However, the work is directed specifically at legislative advocacy,13,14,20,24 which limits the applicability to general advocacy instruction.

The primary objective of this study was to develop a consensus definition for “advocacy for the profession of pharmacy” with a secondary objective of developing consensus regarding core competencies for PharmD graduates to be effective advocates for the profession.

METHODS

The Delphi technique was originally developed as a survey approach in 1948 and has since been adopted in social sciences, medical, nursing, and health services research.25-27 The Delphi technique is an iterative multistage process designed to combine the opinions of individual participants, or “experts” into group consensus through administration of a series of structured anonymous questionnaires called rounds. As part of the process, the responses from each questionnaire are provided back in a summarized form to the participants. By using successive questionnaires, opinions are considered in a non-adversarial manner, with the current status of the groups’ collective opinion being repeatedly relayed back to participants.26

This study consisted of a 3-round modified Delphi process using the Web-based survey software program Qualtrics (Qualtrics Labs Inc., Provo, Utah). One modification to the Delphi process involves beginning the first round with 1 or more carefully selected items.28 For this study, an initial definition for the phrase “advocacy for a profession” was used, based on a synthesized review of the literature.

Powell states that “the success of a Delphi study clearly rests on the combined expertise of the participants who make up the expert panel.”29 To that end, Delphi researchers have commented on criteria for expert selection, including competency within the specialized area30 and credibility.29 Heeding this direction, inclusion criteria for this study consisted of appointment to the Annals of Pharmacotherapy Health Care Policy Panel31 (members all are faculty members in colleges or schools of pharmacy) or authorship of an advocacy-related chapter in the textbook APhA Leadership and Advocacy for the Profession.32 This combination of criteria gathered experts who had knowledge in advocacy, as well as some familiarity with teaching advocacy and PharmD curricula.

The optimal number of experts needed for a Delphi is not agreed upon in the literature.29,30,33,34 Delbecq and colleagues suggested that 10 to 15 subjects is a sufficient number if the subjects are homogenous.35 However, Brockhoff has studied the performance of Delphi groups of 5 to 11, concluding that increasing the group size does not necessarily increase group performance.36 After considering the pool of available experts and its homogeneity, a panel size of 6 to 10 was deemed appropriate.

Although a wide variety of recommendations regarding consensus levels for a Delphi study were found in the literature,29 no definitive guidelines could be found.29,34 Loughlin and Moore defined consensus as 51% agreement.37 Typically, agreement is no lower than 55%, and potentially up to 100%.29 For this study, consensus was defined prior to study initiation as 75% of participants agreeing or strongly agreeing with the definition and 75% of participants declaring a competency “very important.” The study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

Round 1

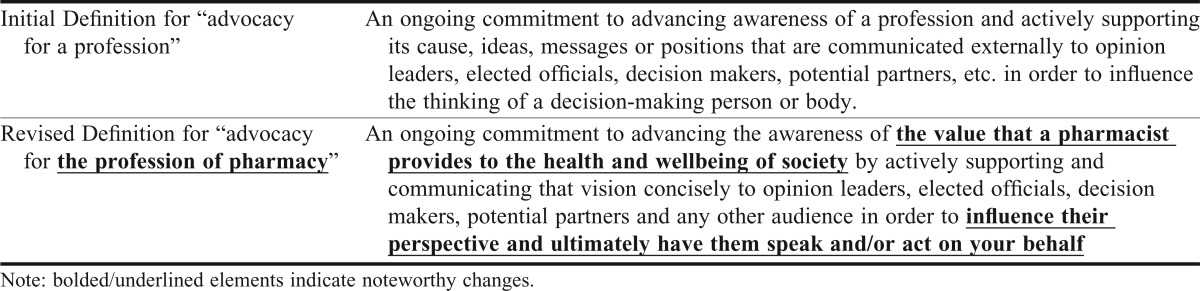

Participants were given a definition of the phrase “advocacy for a profession” (Table 1), which was developed by analyzing each reference to the term advocacy in the text APhA Leadership and Advocacy for the Profession32 for common elements regarding motivation/reason for advocating, actions involved while advocating, factors influencing advocacy, and the result of advocacy. A 5-point Likert scale assessing each participant’s strength of agreement (ie, strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree) followed the definition. Via open text response, participants were asked to provide their opinions regarding aspects of the definition that resonated well, did not fit, and were absent. Beginning the process with refinement of the definition provided the panel participants with context to operate from during the development of the competency statements. Participants were also asked “What activities, actions and/or contributions are required to be an effective advocate for the profession?” and “What characteristics or personal attributes does an advocate generally possess?” These data were reviewed for themes by the authors prior to the second round. A report was created for the Delphi participants that consisted of draft competency statements derived from the themes, with direct quotes from the participants as supporting evidence for the statements.

Table 1.

Determining a Consensus Definition for Advocacy for a Profession

Round 2

Participants received the report from round 1. In addition, they were provided with a revised version of the definition (Table 1). Participants rated their agreement with the definition using the same 5-point Likert scale used in round 1. Recognizing that consensus may not be reached during this round, participants indicating “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” or “neither agree nor disagree” were provided an opportunity to recommend further changes, additions, or removals.

Participants were also given the opportunity to provide feedback for each competency statement regarding what resonated well with them, what did not fit, and what was missing. The study investigators used this feedback to modify the competency statements to propose final statements in round 3.

Round 3

During the final round, participants were provided each modified competency statement with descriptive comments and asked 2 questions for each competency: “How important is this competency for being an effective advocate for the profession of pharmacy?” and “How important is it that this competency be addressed during entry-level PharmD education?” both of which were rated on a 3-point Likert scale (not important, neutral, or very important).

RESULTS

Round 1

Nine subjects elected to participate in the first round, resulting in a panel size within the target range. The initial proposed definition for “advocacy for a profession” (Table 1) achieved 67% agreement with 2 participants indicating strong disagreement. From the responses gathered in the first round for revisions to the definition, 3 removals, 5 modifications, and 8 additions were proposed. In addition, the group recommended 35 characteristics or personal attributes of an advocate and 36 activities, actions, or contributions of an advocate to be considered when developing competency statements.

Round 2

In round 2, the same 9 individuals participated, resulting in 100% retention. After analyzing the feedback provided for the definition in round 1, the definition was modified to place more focus on the profession of pharmacy and to incorporate other recommendations. Noteworthy modifications to the definition are highlighted in bold writing in Table 1. This new definition achieved consensus, with 7 of 9 participants (78%) agreeing or strongly agreeing and no participants indicating strong disagreement.

Four knowledge-based competency statements were drafted based on the input provided in round 1. Upon reviewing these competency statements, participants proposed 5 removals, 3 revisions, and 16 additions. Likewise, the characteristics and personal attributes of an advocate proposed in round 1 were drafted into 5 skills-based competency statements. These statements solicited recommendations for 3 removals, 9 modifications, and 13 additions. Additionally, a tenth competency statement was created based on feedback in round 2 describing a need for advocates to know what communication tools and media sources are available to assist them in their advocacy activities. This statement was separate from and in addition to 1 of the other 9 that addressed advocates’ need to possess a communications skill set.

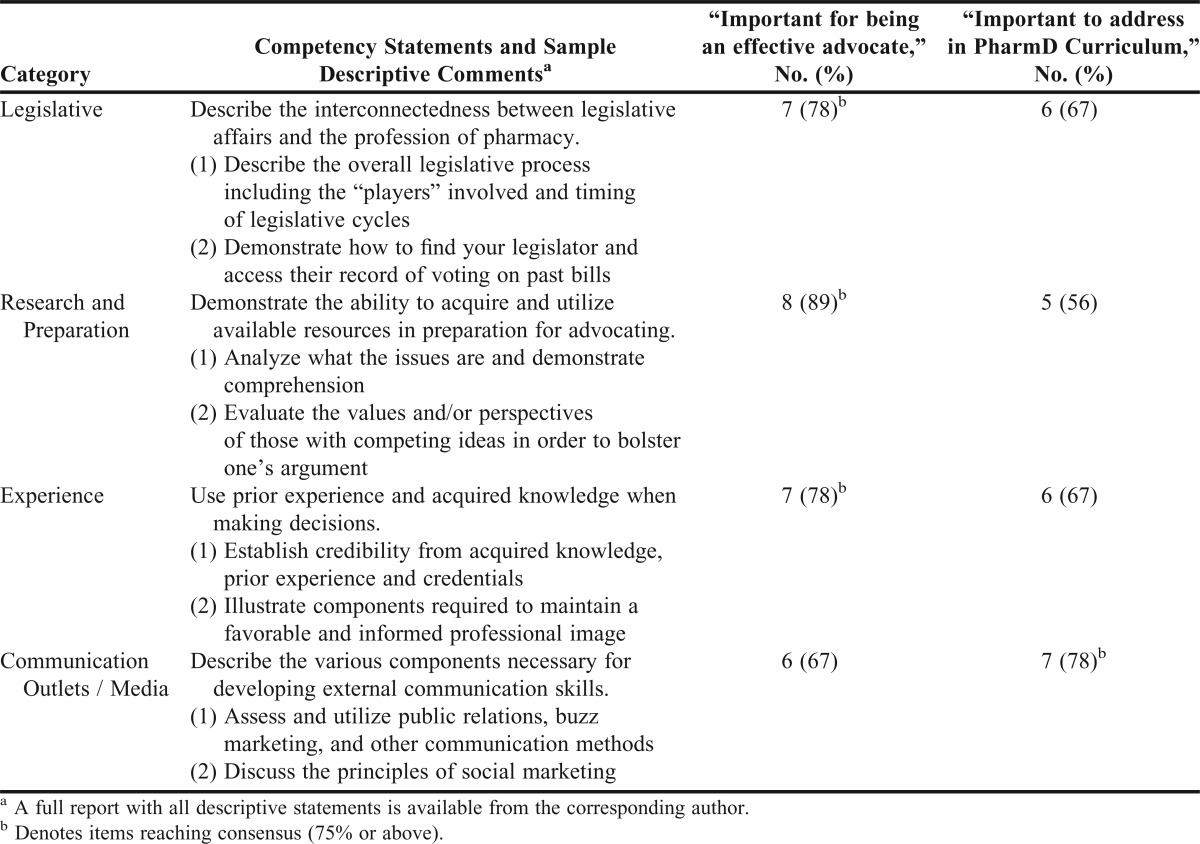

Round 3

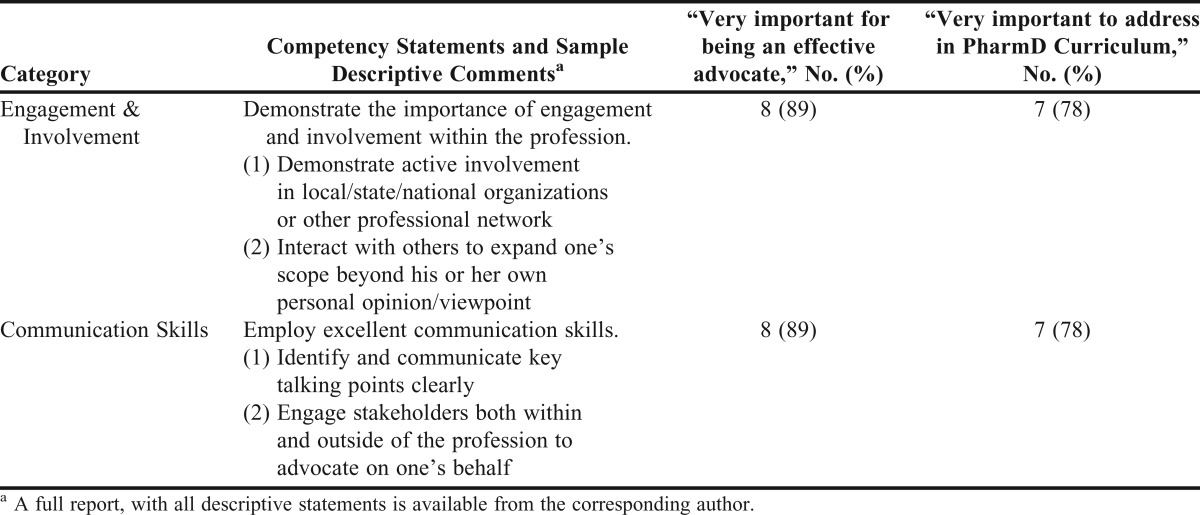

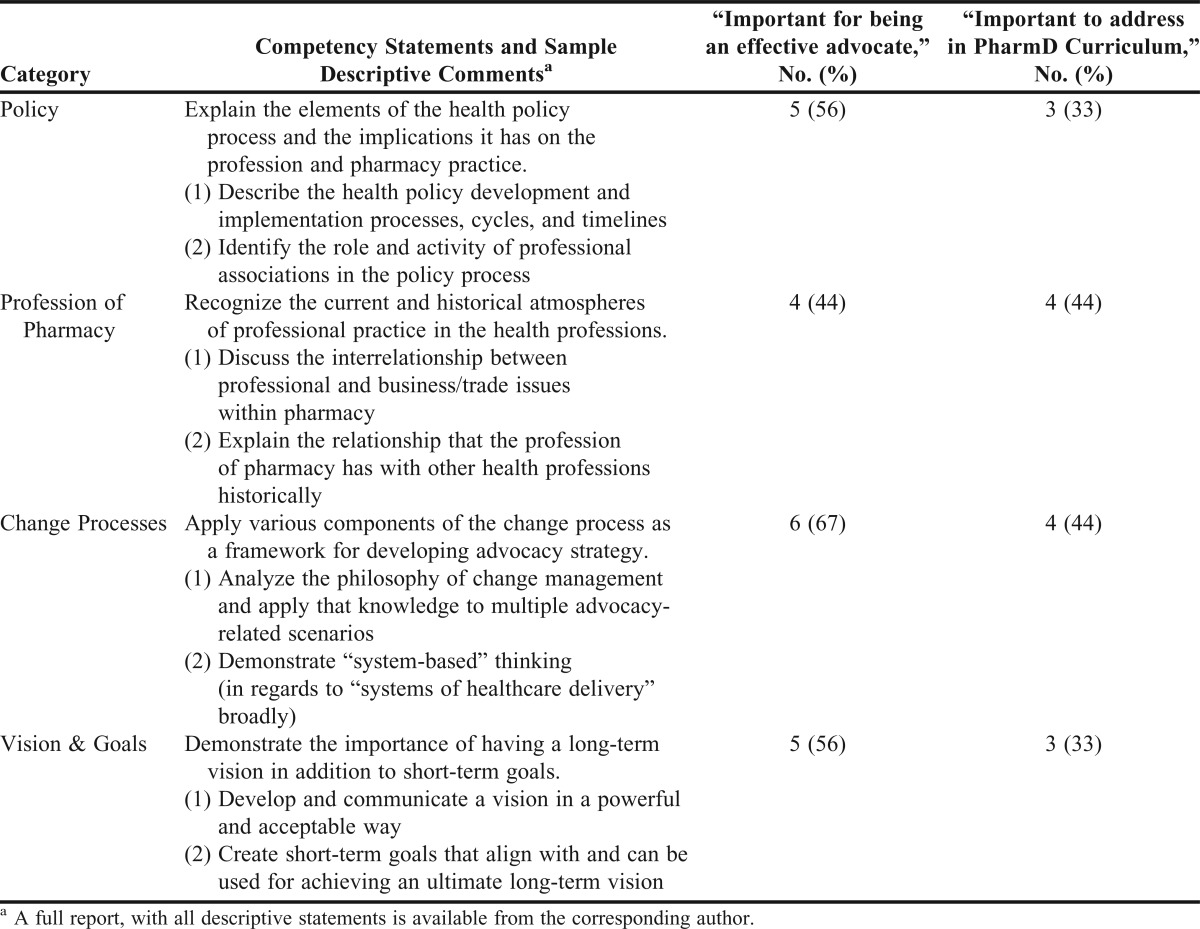

In round 3, the same 9 individuals participated, maintaining the 100% retention rate. This round was used to determine the degree of agreement with the amended competency statements among members of the group. Of the 10 proposed competency statements, 2 statements achieved a consensus for importance for being an effective advocate (8/9 or 89% for both) and the importance of addressing the competency in PharmD education (7/9 or 78% for both) (Table 2). Additionally, 3 competency statements achieved consensus for the importance of being an effective advocate, but not for the importance of addressing these competencies in the PharmD curriculum. Conversely, 1 statement did not reach consensus on the importance of being an effective advocate, but did on the importance for including in the PharmD curriculum (Table 3). Finally, 4 competency statements did not reach consensus for their importance to either advocacy or inclusion in the curricula (Table 4).

Table 2.

Competency Statements Achieving Consensus for Both Importance for Being an Advocate and Importance to Address in PharmD Curricula (N = 9)

Table 3.

Competency Statements Achieving Consensus in Either Importance for Being an Advocate or Importance to Address in PharmD Curricula (N = 9)

Table 4.

Competency Statements Not Achieving Consensus in Either Importance for Being an Advocate or Importance to Address in PharmD Curricula (N = 9)

DISCUSSION

This investigation sought to determine a consensus definition for “advocacy for the profession of pharmacy” and the competencies necessary to effectively advocate. Achieving a consensus definition is an important milestone. Without a common focal point (definition) and goals (desired competencies), it is impossible to provide consistent and effective learning experiences on a national and international level to student pharmacists at different colleges and schools of pharmacy.

Definition

The initial definition emphasized many broad aspects along the entire spectrum of advocacy including the motivation/reason for advocating, actions involved while advocating, factors influencing advocacy, and the result of advocacy. A broad definition allows recognition and inclusion of the many different opportunities to advocate for pharmacy beyond legislative advocacy. For example, pharmacists may advocate to administrators at a practice site for expanded clinical pharmacy services, specific patients regarding the importance of having a pharmacist involved in his or her health care, and insurance companies regarding clinical pharmacy services coverage. Having a definition for advocacy that applies to all of these instances ensures that student pharmacists are learning highly transferable knowledge and skills that are relevant in many settings and situations.

Even though the initial definition achieved 67% agreement, that was below the predefined consensus level and 2 participants strongly disagreed, which indicated that more revisions were needed. From the initial definition, reported elements that resonated well were the concepts of “ongoing commitment,” “advancing awareness,” “active support,” and “persuasion/influence.” Many of the suggested removals were related to word and phrase selection, such as the terms “externally,” “influence the thinking,” and “cause.” A few notable conceptual changes that were suggested were to incorporate terminology specifically referencing pharmacy, to focus more broadly from an interprofessional perspective on the health/well-being of society, and to acknowledge that advocacy can affect any audience, not just a decision-making body (Table 1). Many of the suggested additions to the definition were personal attributes (eg, effective communicator, good interpersonal skills) or acquired knowledge of the advocate (eg, use of high-quality evidence and continuous reflective quality improvement, well-informed). These were incorporated into the draft competency statements.

Competency Statements

The “engagement & involvement” and “communication skills” competencies were the only statements that achieved consensus for importance in being an effective advocate and importance in the PharmD curriculum (Table 2). Several participants commented on the importance of being involved in professional organizations as a student to develop a broader awareness of the profession beyond the classroom and personal work experiences. This is consistent with the recommendation from the authors of the AACP Curricular Reform Summit white paper15 who noted that student professional organizations should be geared towards providing students with leadership and professional advocacy opportunities rather than social networking opportunities. To convey a compelling message, communication skills (including written, verbal, and interpersonal) are also frequently noted as essential for advocacy.14,24 Several pharmacy advocacy courses have exercised these skills by using debates in their course activities.21,23

The competency statement regarding “Legislative Affairs” received mixed responses (Table 3). Participants made comments such as “most critical,” “we must recognize that practice is influenced by legislation, politics, and thought leaders,” and “this is important ‘baseline’ information that is fairly straightforward.” However, opposing comments downplayed the importance of competency in legislative affairs stating, “…it is not as important as the policy and advocacy process.” Another respondent attempted to put the competency in context, stating “the broad definition implies that advocacy is not limited to a legislative audience but this [competency] focus[es] on the legislative process.” These opposing perspectives demonstrate the lack of consensus that currently exists regarding the scope of advocacy and further reinforce the need for a consensus definition. Additional discussion is needed to assist the academy in articulating the desired competencies related to the advocacy process and in defining the role of legislative-related competencies in the PharmD curricula.

The competency statements in the “research and preparation” and “experience” categories achieved consensus for importance in being an effective advocate, but not for importance for the PharmD curriculum (Table 3). Comments described the statements as “generic,” “vague,” and “too simplistic.” Further discussion may be needed to refine the initial competencies to be focused, specific, and measurable enough to guide instruction. It may not be possible or ideal to introduce these competencies into the PharmD curricula. For instance, simply practicing as a licensed pharmacist, getting “real-world experience,” might help establish the credibility needed in the “Experience” category. These competencies may be better achieved through postgraduate training in the form of residencies, fellowships, or graduate studies, or through involvement in professional associations. For example, a required objective within the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) PGY1 Residency Outcomes, Goals and Objectives addresses some of the comments, including “using knowledge of the principles of an organization’s political and decision-making structure to influence accomplishing a practice area goal.”38

Complete consensus was almost achieved for the “communication outlets/media” category (Table 3) upon initial introduction to the respondents in round 3. As indicated by the results, a majority of participants felt the competency was important to address in the PharmD curriculum (78%), yet slightly fewer felt it was necessary for being an advocate (67%). One explanation might be that knowledge of communication and media outlets may be valuable for a pharmacist in daily practice regardless of his or her advocacy interests, eg, in advertising pharmacy services or health promotion activities. In fact, media resources are broadly available through several professional associations including the American Pharmacists Association (APhA)39 and the ASHP.40

“Policy,” “profession of pharmacy,” “change processes,” and “vision & goals” did not achieve consensus after 3 rounds of the Delphi process (Table 4). For each of these competency statements, there was little disagreement (ie, no more than 1 participant thought that the competency was “not important to be an effective advocate”). However, most participants reported a neutral opinion. Notably, a majority of participants strongly indicated a preference to include pharmacy-specific terminology in the definition (which was incorporated), yet less than half felt a competency related to knowledge of the profession of pharmacy was important. Additionally, several participants commented that there might not be room in the pharmacy curriculum for each competency. The concerns for space and time may have hindered opinions of importance and led to the large amount of neutrality. Further exploration of these areas is needed.

Limitations of this study include the number of rounds. Having only 3 rounds to determine consensus on competency statements that have not been heavily discussed and debated was ambitious. In particular, additional discussion and debate around the competency areas highlighted in Table 4 may yield refinements to the statements that are agreeable to the academy.

Biased perspectives may also be a concern. This group was called upon because of their focus in advocacy work. Indeed, such a group may be more inclined to incorporate advocacy-related competencies into a curriculum than faculty members and administrators without an interest in this content area. However, consensus was only achieved for 2 competencies, which did not appear to be inappropriately heavy.

This work represents the perspectives of an expert panel. Their work is noteworthy but requires more discussion and debate by wider audiences. Additional perspectives, such as those of students, practicing pharmacists, and organization leaders, would enrich the discussion of advocacy competencies. In addition, the reliance on advocacy experts from within pharmacy can also be viewed as a limitation. Effective advocacy is present in other health professions and would inform our advocacy efforts, as well as advocacy instruction. Future research should obtain this input.

Future research should include further refinement of these competency statements, particularly those for which a consensus was not reached. Methods for achieving the competencies within both classroom and experiential learning will also require investigation, as well as assessment methods. As the discussions regarding advocacy for the profession continue, future work could attempt to define competencies to be achieved through electives, which would be beyond the core competencies for all students.

CONCLUSIONS

This study laid some of the groundwork to determine the knowledge and skills necessary to be an effective advocate for the profession of pharmacy. Using this consensus-derived definition describing advocacy for the profession of pharmacy, subsequent discussions and research can continue to focus more on the competencies of successful advocates and the ideal placement for associated learning experiences. Two competency statements attained consensus as very important for the PharmD curriculum: engagement/involvement and communication skills.

As the AACP, the ACPE, other professional organizations, and the profession of pharmacy as a whole continue to encourage current and future pharmacists to be involved in advocacy activities, the profession must come together to further define the competencies required. Ultimately, advocacy-related competencies will need to be incorporated where appropriate (eg, core PharmD curricula, electives, PGY1 residency training, graduate programs) to ensure all future pharmacists have relevant training in advocacy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gehrke PM. Civic engagement and nursing education. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2008;31(1):52–66. doi: 10.1097/01.ANS.0000311529.73564.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wade GH. Professional nurse autonomy: concept analysis and application to nursing education. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30(2):310–318. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacDonnell JA. Fostering nurse’s political knowledges and practices: education and political activation in relation to lesbian health. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2009;31(2):158–172. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181a3ddd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sgro S, Happell B. Politicize or perish! the importance of policy for Australian psychiatric-mental health nurses. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2006;7(2):136–141. doi: 10.1177/1527154406288274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrington C, Crider MC, Benner PE, Malone RE. Advanced nursing training in health policy: designing and implementing a program. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2005;6(2):99–108. doi: 10.1177/1527154405276070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borthwick C, Galbally R. Nursing leadership and health sector reform. Nurs Inq. 2001;8(2):75–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1800.2001.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorensen R, Iedema R, Severinsson E. Beyond profession: nursing leadership in contemporary health care. J Nurs Manag. 2008;16(5):535–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reutter L, Williamson DL. Advocating healthy public policy: implications for baccalaureate nursing education. J Nurs Educ. 2000;39(1):21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huddle TS. Medical professionalism and medical education should not involve commitments to political advocacy. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):378–383. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086efe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobsohn V, DeArman M, Moran P, et al. Changing hospital policy from the wards: an introduction to health policy education. Acad Med. 2008;(83):352–356. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181667d6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Perspective: physician advocacy: what is it and how do we do it? Acad Med. 2010;85(1):63–67. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c40d40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilboy MR, Harris J, Lazarow HL. Public policy in undergraduate dietetics education: challenges and recommendations. Top Clin Nutr. 2010;25(2):109–117. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hearne SA. Practice-based teaching for health policy action and advocacy. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 2):65–70. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allegrante JP, Moon RW, Auld ME, Gebbie KM. Continuing-education needs of the currently employed public health education workforce. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(8):1230–1234. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ACPE. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education; January 23, 2011. Adopted . [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jungnickel PW, Kelley KW, Hammer DP, Haines ST, Marlowe KF. Addressing competencies for the future in the professional curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article 156. doi: 10.5688/aj7308156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rains JW, Barton-Kriese P. Developing political competence: a comparative study across disciplines. Public Health Nurs. 2001;18(4):219–224. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Advocacy [definition] Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. 11th ed. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shore MF. Beyond self-interest: professional advocacy and the integration of theory, research and practice. Am Psychol. 1998;53(4):474–479. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.4.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galer-Unti RA, Tappe MK, Lachenmayr S. Advocacy 101: getting started in health education advocacy. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5(3):280–288. doi: 10.1177/1524839903257697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyle CJ, Beardsley RS, Hayes M. Effective leadership and advocacy: amplifying professional citizenship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3):Article 63. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith K, Hazlet TK, Hammer DP, Williams DH. “Fix the law” project: an innovation in students’ learning to affect change. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1):Article 18. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blake EW, Powell PH. A pharmacy political advocacy elective course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(7):Article 137. doi: 10.5688/ajpe757137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waterston T. Teaching and learning about advocacy. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2009;94(1):24–28. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.141762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKenna HP. The Delphi technique: a worthwhile research approach for nursing? J Adv Nurs. 1994;19(6):1221–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penciner R, Langhan T, Lee R, Mcewen J, Woods RA, Bandiera G. Using a Delphi process to establish consensus on emergency medicine clerkship competencies. Med Teach. 2011;33(6):e333–e339. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.575903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Custer RL, Scarcella JA, Stewart BR. The modified Delphi technique – a rational modification. J Vocat Tech Educ. 1999;15(2) http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/JVTE/v15n2/custer.html. Accessed November 4, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powell C. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(4):376–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu C-C, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12(10):1–8. http://pareonline.net/pdf/v12n10.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matzke GR. Health-care policy 2011: implications for pharmacists. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(3):412–413. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyle CJ, Beardsley RS, Holdford DA, editors. Leadership and Advocacy for Pharmacy. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams PL, Webb C. The Delphi technique: a methodological discussion. J Adv Nurs. 1994;19(1):180–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. Consulting the oracle: ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(2):205–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delbecq AL, Van de Ven AH, Gustafson DH. Group Techniques for Program Planning: A Guide to Nominal Group and Delphi Processes. Vol. 10. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman, and Co.; 1975. p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brockhoff K. The performance of forecasting groups in computer dialogue and face-to-face discussion. In: Linstone HA, Turoff M, editors. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; 2002. pp. 285–311. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loughlin K, Moore L. Using Delphi to achieve congruent objectives and activities in a pediatrics department. J Med Educ. 1979;54(2):101–106. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197902000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Required and Elective Educational Outcomes, Goals, Objectives, and Instructional Objectives for Postgraduate Year One (PGY1) Pharmacy Residency Programs. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Pharmacists Association. American pharmacists month. http://www.pharmacist.com/american-pharmacists-month-2012. Accessed August 3, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. National hospital and health-system pharmacy week. http://www.ashp.org/pharmweek. Accessed July 21, 2012. [Google Scholar]