Abstract

The spatial distribution of molecular signals within cells is crucial for cellular functions. Here, as a model to study the polarized spatial distribution of molecular activities, we used cells on micro-patterned strips of fibronectin with one end free and the other end contacting a neighboring cell. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and the small GTPase Rac display greater activity at the free end, whereas myosin II light chain (MLC) and actin filaments are enriched near the intercellular junction. PI3K and Rac polarization depend specifically on the N-cadherin-p120ctn complex, whereas MLC and actin filament polarization depend on the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex. Integrins promote high PI3K/Rac activities at the free end, and the N-cadherin–p120ctn complex excludes integrin α5 at the junctions to suppress local PI3K and Rac activity. We hence conclude that N-cadherin couples with distinct effectors to polarize PI3K/Rac and MLC/actin filaments in migrating cells.

Introduction

Directional and collective cell migration in vivo, such as endothelial, immune and fibroblast cells migrating toward ischemic tissues and wounds, is crucial for tissue remodeling and organism survival1. Efficient migration requires cell polarization, with distinct activities at the leading edge and trailing regions2. The major driving forces in migrating single cells are from Rac-dependent actin polymerization at the leading edge and Rho-dependent acto-myosin contraction at the rear. Multiple mechanisms contribute to Rac polarization and the subsequent actin polymerization at the leading edge2,3. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and its lipid product phosphatidyl inositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) are concentrated at the lead edge and recruit Rac guanine-nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) to the plasma membrane to activate Rac4,5. Rac in turn can regulate PI3K activity via both direct binding6 and through downstream pathways, including superoxide5 to establish a positive feedback loop1. A second positive feedback loop involves integrins, which also activate Rac at the leading edge through multiple mechanisms1,7,8, while Rac promotes formation of new adhesion and localization of high-affinity integrins at the leading edge9. At the rear, Rho controls the assembly of acto-myosin to generate contractile force and promote detachment of the cell tail2. The acto-myosin machinery consists of myosin II and actin stress fibers, regulated by the coordination of myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation and Ca2+ at subcellular locations10. Despite these well-established mechanisms, it remains unclear how these processes are integrated temporally and spatially across the cell2.

During collective migration in vivo, neighboring cells remain connected through cadherin-mediated adherens junctions11. The intracellular tail of classic cadherins contains a juxtamembrane domain (JMD) that binds p120catenin (p120ctn) and a C-terminal domain (CBD) that binds β-catenin12. P120ctn regulates cadherin stability13 and Rho GTPases14,15. β-catenin interacts with α-catenin, which can further couple to the actin cytoskeleton12. As such, connected to various signaling molecules, cadherins not only establish junctions but also regulate molecular polarity during migration. For example, N-Cadherin is required for MTOC orientation and directional migration of smooth muscle cells16. Similarly, E-cadherin mediates the effect of the mammalian Scribble (Scrib) polarity protein on directed migration of epithelial Madin-Darby canine kidney cells17. Elegant studies also indicate that N/E-cadherin can regulate cell polarization, including the polarized distribution of centrosome, lamellipodia dynamics, and Rac1 activity18–20. However, the underlying mechanism by which cadherins coordinate and integrate the signaling network to regulate molecular polarity at subcellular levels remains poorly understood.

Integrin-mediated cell-ECM and cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesions jointly regulate many cellular functions21. For example, integrin-dependent actomyosin contraction physically ruptures E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell contacts during the scattering of epithelial cells22. Integrin-mediated activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Src can affect the junction stability through the phosphorylation of cadherin/catenin23. Conversely, perturbing N-cadherin induces translocation of the non-receptor tyrosine kinase Fer from cadherin to the integrin complex and modulates the integrin-mediated adhesions24,25. E-cadherin can regulate Rap1 localization to suppress integrin function26. In contrast, TGFβ-induced loss of E-cadherin promotes the assembly of β1 integrin-dependent focal adhesions26,27. In response to mechanical shear stress stimulation, VE-cadherin, together with PECAM1 and VEGFR2, stimulate activation of integrin αvβ3 in endothelial cells28.

In this study, we combine micro-patterning technology with molecular biosensors for live cell imaging to study the coordination between cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesions in polarizing molecular signals. We found that N-cadherin-mediated adherens junctions promote activation of PI3K and Rac at the cell free end through p120ctn, which suppresses integrins near the junction. Additionally, N-cadherin promotes accumulation of MLC and actin filaments (FA) near the cell-cell junction through β-catenin. In summary, our results revealed a new molecular hierarchy in which N-cadherin regulates the subcellular distributions of different signaling molecules through distinct effectors.

Results

Distinct polarization patterns for PI3K/Rac and MLC/AF

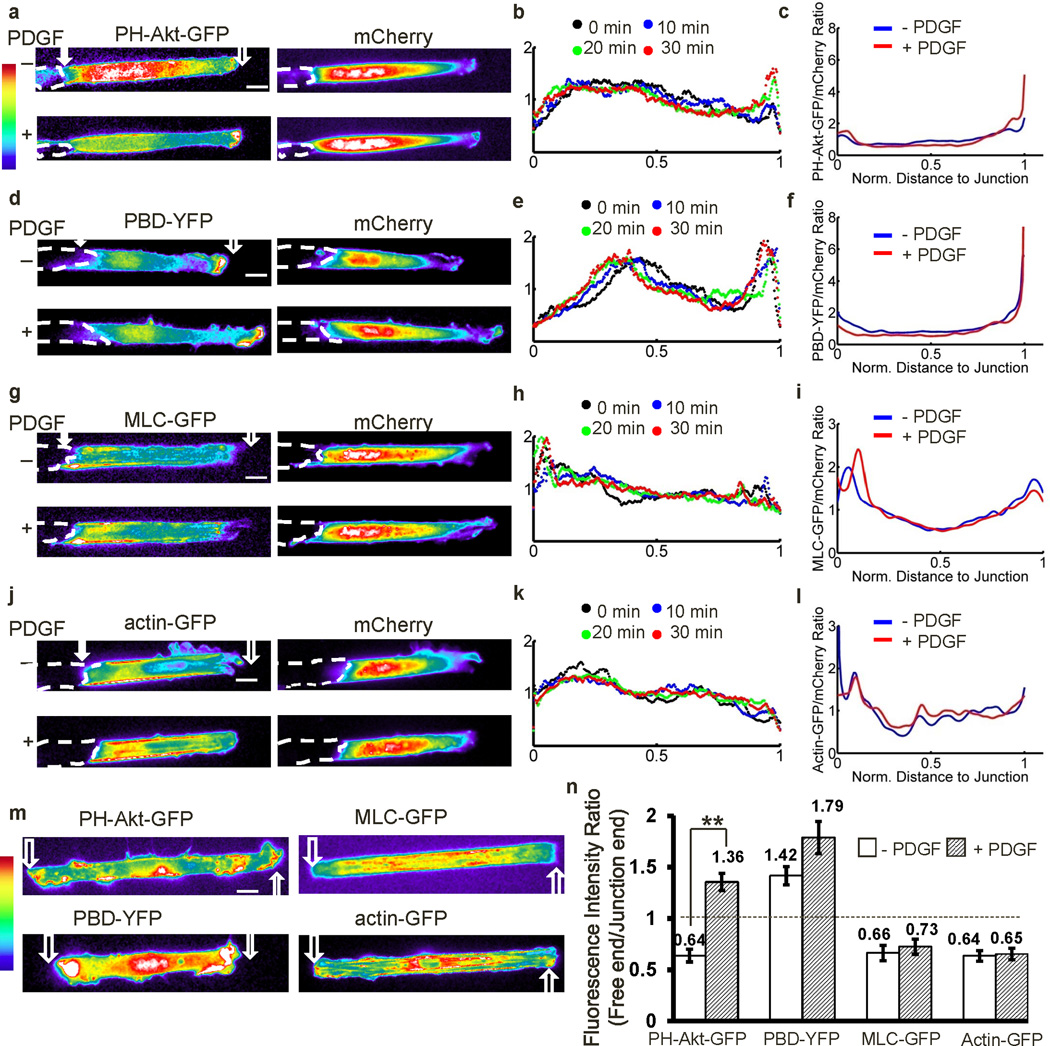

To study the role of cell-cell adhesions in coordinating signaling transduction at subcellular levels, we developed a cell model in which MEFs were seeded on fibronectin-coated strips with one end of the cell free and the other end contacting a neighboring cell (Supplementary Fig. S1a, and Supplementary Movie 1). We first examined the subcellular distribution of PI3K and Rac activities, which regulate leading edge protrusion, and MLC and AF, which mediate cell contraction2. The GFP-fused PH domain of Akt (PH-Akt-GFP), which binds PIP3, was used to visualize the spatial distributions of PI3K activity29. PH-Akt-GFP fluorescence was diffusive in resting cells, but accumulated at the free end upon PDGF stimulation (Fig. 1a, and Supplementary Movie 2 upper panel). PDGF-induced polarization and translocation of PH-Akt-GFP started immediately after PDGF treatment and continued for about 10–20 min to reach stabilization of the polarity (Supplementary Fig. S1b, and Supplementary Movie 3). In contrast, the co-transfected fluorescent protein mCherry in these cells did not significantly translocate to the cell periphery following PDGF (Fig. 1a). Quantification of the fluorescence intensity distribution and GFP/mCherry ratio along the strip direction (Supplementary Fig. S2, quantification procedure detailed in Methods) confirmed the clear accumulation of PH-Akt-GFP but not mCherry at the free end upon PDGF stimulation (Fig. 1b–c and Supplementary Fig. S3a).

Figure 1. The polarization of molecular signals.

MEFs transfected with various fluorescent probes were seeded on Fn-coated strips (10 µm in width), with one end free and the other end contacting a neighboring cell. The broken white lines represent the body contours of neighboring cells physically contacting the cells of interest. The hollow and filled arrows on the images indicate the positions of the free and junction ends respectively. (a–l), the fluorescence intensity distributions of mCherry together with (a–c) PH-Akt-GFP (n=4), (d–f) PBD-YFP (n=5), (g–i) MLC-GFP (n=4), or (j–l) actin-GFP (n=4) before and after PDGF stimulation. (a, d, g and j) The pseudo color images represent the fluorescence intensity of different probes as indicated, with cold and hot colors representing low and high fluorescence intensities, respectively; (b, e, h, and k) The intensity distributions of indicated probes averaged along the strip direction before and after PDGF stimulation for various periods of time as indicated. (c, f, i, l) The averaged intensity ratios between the indicated probe and co-transfected mCherry along the strip direction before and after PDGF stimulation. (m) The fluorescence intensity images of the four probes: PH-Akt-GFP, PBD-YFP, MLC-GFP, and actin-GFP, in micropatterned MEFs without any cell-cell contact. (n) The bar graphs represent the polarity, or intensity ratios between the free and junction end as described in Methods (mean ± SEM, Student’s t-test, * represents P<0.05 and ** P<0.01). – PDGF: before PDGF; + PDGF: after PDGF stimulation. (Scale bars, 10 µm.)

YFP-tagged p21 binding domain of p21-activated kinase (PAK-PBD-YFP), was used to localize active Rac10,30. As shown in Figure 1d–f, active Rac monitored by PAK-PBD-YFP was concentrated at the free end before and after PDGF stimulation (Supplementary Fig. S3b, and Supplementary Movie 2 lower panel). Interestingly, MLC and AF visualized with GFP-tagged MLC (MLC-GFP)31 and GFP-tagged β-actin (actin-GFP) were concentrated near the junction both before and after PDGF stimulation (Fig. 1g–l, Supplementary Fig. S3c–d, and Supplementary Movie 4), possibly promoting the junction stability32. In contrast, cells without a contacting neighbor were not polarized (Fig. 1m, and Supplementary Fig. S3e). We conclude that cell-cell contacts regulate the polarized distribution of these signaling and cytoskeletal molecules/activities.

To further quantify these asymmetric molecular distributions, we calculated the ratio of fluorescence intensities between the free and junctional ends (see the Materials and Methods section and Supplementary Fig. S2). The average ratios of PH-Akt-GFP at the front/rear significantly increased from 0.64 to 1.36 after PDGF stimulation, indicating that PI3K activity polarized toward the free end after PDGF stimulation. Meanwhile, the intensity ratio of PAK-PBD-YFP was 1.42 and 1.79 before and after PDGF stimulation, respectively. This indicates that Rac activity polarization toward the free end that does not require but slightly increases with PDGF. Further, MLC-GFP and actin-GFP had low ratio values before or after PDGF, suggesting that MLC and AF were concentrated proximal to the junction independent of PDGF. Additionally, the polarity indices of all four signals (PI3K/Rac activities, and MLC/actin distributions) from individual cells were averaged from multiple frames within 5 minutes before, or during 20–30 minutes after PDGF stimulation. These temporally averaged polarity indices were compared with the measurements based on randomly selected individual time points. The results indicate that these two methods give very similar results (Supplementary Fig. S4). This result is consistent with the stable intracellular gradients observed after treatment with PDGF.

To exclude an effect of cell morphology on these effects, cells were co-transfected with each one of the probes plus mCherry. The intensity of the probe and mCherry were determined and collectively smoothed in each individual cell with the moving average method. The ratio between the smoothed intensity curves of probe and mCherry was then calculated and averaged from multiple samples (Figs. 1c, f, i, l). These ratios (probe/mCherry) showed similar polarity as the corresponding curves before normalization, with PI3K and Rac higher at the free end, and MLC and F-actin enriched at the junctional end. The observed polarization is therefore not an artifact of effects on cell shape or volume.

As an additional set of controls, we also examined the dependence of the fluorescence probes on relevant molecular activities. The PDGF-induced PH-Akt-GFP accumulation at the free end was abolished by the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, but not by the MLCK inhibitor ML-7 (Supplementary Fig. S5a, and Supplementary Movie 3). Polarization of PAK-PBD-YFP was also significantly inhibited by LY294002 (Supplementary Fig. S5b, and Supplementary Movie 5), confirming that Rac is downstream of PI3K although LY294002 treatment caused cell contraction possibly due to the reduction of actin polymerization and membrane protrusion as well as the destabilization of focal adhesions at the free end after the inhibition of PI3K/Rac activities33,34. PAK-PBD-YFP polarization was also blocked by dominant negative Rac (RacN17), but not by ML-7 (Supplementary Fig. S5b). In contrast, ML-7, but not LY294002, blocked the polarization of MLC-GFP (Supplementary Fig. S5c). Cytochalasin D, but not ML-7 nor LY294002, blocked the actin-GFP polarization (Supplementary Fig. S5d). These results support the specificity of the probes used in these studies, and suggest that PI 3-kinase/Rac and actin/myosin are regulated independently.

N-cadherin regulates the polarity of Rac/PI3K and MLC/AF

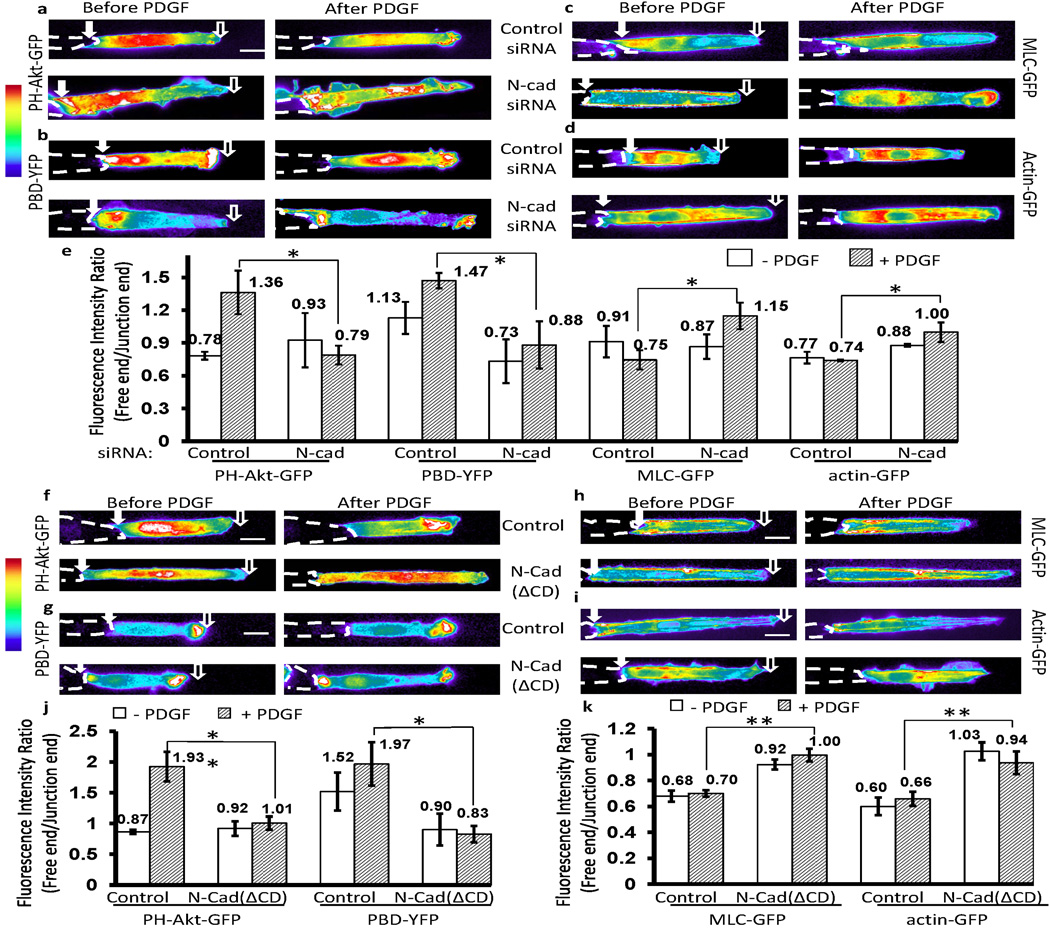

In fibroblasts, the major classical cadherin at cell-cell adherens junctions is N-cadherin35,36. We therefore asked whether N-cadherin regulates the observed polarities in this system. Knockdown of N-cadherin by siRNA in MEFs inhibited polarization of both PI3K/Rac activities and MLC/AF (Fig. 2a–d, and Supplementary Fig. S6a–b; quantified in Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. S6c), although the physical cell-cell contact remained relatively intact (Supplementary Fig. 7). In fact, following knockdown, PI3K and Rac activities were high at both the free and junction ends (Fig. 2a–b). These molecular signals were unpolarized in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells lacking classic endogenous cadherins but re-polairzed when N-cadherin was expressed37 (Supplementary Fig. S8). Thus, N-cadherin mediates the polarization of PI3K/Rac activities and MLC/AF distributions. In support of this notion, the N-cadherin-neutralizing antibody GC-438 inhibited polarization of these components (Supplementary Fig. S9a).

Figure 2. N-cadherin mediates the polarity of PI3K/Rac activities and MLC/AF distributions.

(a–d) MEFs were co-transfected with N-cadherin siRNA (50 nM) or control scramble siRNA (50 nM) together with the fluorescent probes (a) PH-Akt-GFP, (b) PBD-YFP, (c) MLC-GFP, or (d) actin-GFP. The pseudo-colored fluorescence intensity images showed the distributions of these probes in MEFs before and after PDGF stimulation. Representative images were selected generally within 20–40 min after PDGF stimulation. (e) The bar graphs represent different probe ratios (mean ± SEM, n=4, * represents P<0.05) of the fluorescence signal between the free and junction end of cell groups shown in (a–d). (f–i) The intensity images of (f) PH-Akt-GFP, (g) PBD-YFP, (h) MLC-GFP, or (i) actin-YFP before and after PDGF stimulation in MEFs transfected with or without N-cad(ΔCD). (j and k) The bar graphs (mean ± SEM, n for each group was shown on Supplementary Fig. S11a–d, Student’s t-test, * represents P<0.05 and ** P<0.01) show the fluorescence intensity ratio (free/junction) of different probes in cell groups shown in (f–g) and (h–i), respectively. (Scale bars, 10 µm)

To identify the regions of N-cadherin required for the observed molecular polarization, we generated a series of N-cadherin dominant negative mutants: N-Cad(ΔCD), N-Cad(Δp120), or N-Cad(Δβ-catenin), in which the entire cytoplasmic tail or the binding domain for either p120ctn or β-catenin was truncated (Supplementary Fig. S9b)12,14. Similar cadherin truncation mutants were previously used to dissect the cadherin/p120ctn and cadherin/β-catenin pathways39–41. The HA tag at the C-terminus of the cadherin mutants facilitates specific staining for the exogenous proteins (Supplementary Fig. S9b). Co-immunoprecipitation confirmed that N-Cad(ΔCD) failed to bind either p120ctn or β-catenin, whereas N-Cad(Δp120) or N-Cad(Δβ-catenin) had impaired binding of p120ctn or β-catenin only (Supplementary Fig. S9c). Nevertheless, N-Cad(ΔCD), N-Cad(Δp120), or N-Cad(Δβ-catenin), with their extracellular domains intact, still localized to cell-cell junctions (Supplementary Fig. S9d), although N-Cad(ΔCD) displayed less stability at junctions with altered morphology (Supplementary Figs. S9d). We further compared the distribution of the exogenous and endogenous N-cadherins, using HA antibody to recognize the exogenous N-cadherin or an N-cadherin antibody that reacts with the N-cadherin cytoplasmic domain. Thus, N-cad(ΔCD) can only be recognized by the HA antibody, while the endogenous N-cadherin only by the N-cadherin antibody. We observed that both exogenous N-cad(wt) and N-cad(ΔCD) localized at junctions, with N-cad(ΔCD) displacing the endogenous N-cadherin from junctions, as indicated by weaker junctional N-cadherin staining and certain suppression of endogenous N-cadherin expression level by exogenous N-cad(ΔCD) (Supplementary Fig. S10). Immunostaining confirmed that N-Cad(Δp120) or N-Cad(Δβ-catenin) prevented the specific recruitment of endogenous p120ctn or β-catenin at junctions, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S11a). Therefore, the expression of exogenous N-cadherin mutants can dominantly suppress the localization/function of their endogenous counterparts.

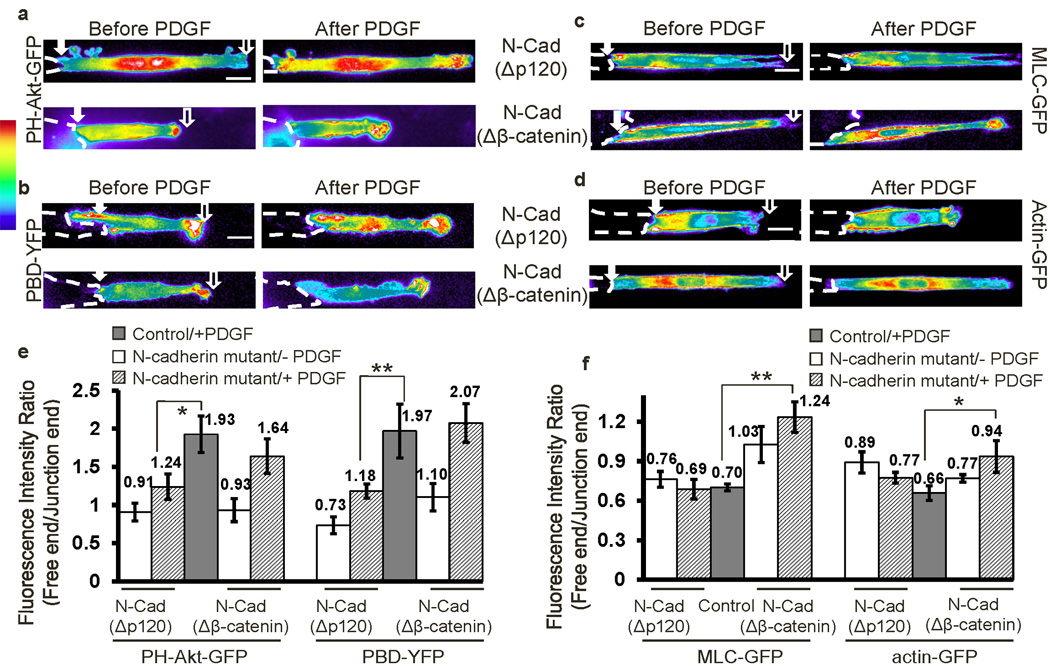

N-Cad(ΔCD), which does not bind p120ctn or β-catenin, clearly abolished polarization of both PI3K/Rac activities and MLC/AF distributions (Fig. 2f–i; quantified in Fig. 2j–k). Interestingly, N-Cad(Δp120) only eliminated polarization of PI3K and Rac activities, resulting in activation at both ends of the cell, but without significant effect on MLC or AF (Fig. 3a–d; Supplementary Movies 6 and 7). In contrast, N-Cad(Δβ-catenin) blocked the polarity of MLC and AF, but not that of PI3K or Rac (Fig. 3a–d, and Supplementary Movie 8). These effects were confirmed by calculating the fluorescence ratios of free/junction ends (Fig. 3e–f) and the averaged curves of fluorescence signals along the strip directions (Supplementary Fig. S12). Expression of N-Cad(Δp120) restored the polarity of MLC/AF but not that of PI3K/Rac activities in CHO cells (Supplementary Fig. S13a), whereas N-Cad(Δβ-catenin) restored the polarization of PI3K/Rac but not MLC/AF (Supplementary Fig. S13b). Thus, distinct regions of the N-cadherin cytoplasmic domain regulate different aspects of the molecular polarity in cells.

Figure 3. P120ctn and β-catenin differentially regulate the polarity of PI3K/Rac and MLC/AF.

The intensity images of (a) PH-Akt-GFP, (b) PBD-YFP, (c) MLC-GFP, or (d) actin-YFP before and after PDGF stimulation in MEFs co-transfected with either N-cad(Δp120) or N-cad(Δβ-catenin) as indicated. (e and f) The bar graphs (mean ± SEM, n for each group was shown on Supplementary Fig. S11a–d, Student’s t-test, * represents P<0.05 and ** P<0.01) represent the fluorescence intensity ratios (free/junction) of different probes in cell groups shown in (a–b) and (c–d), respectively. (Scale bars, 10 µm)

The role of p120ctn and β-catenin

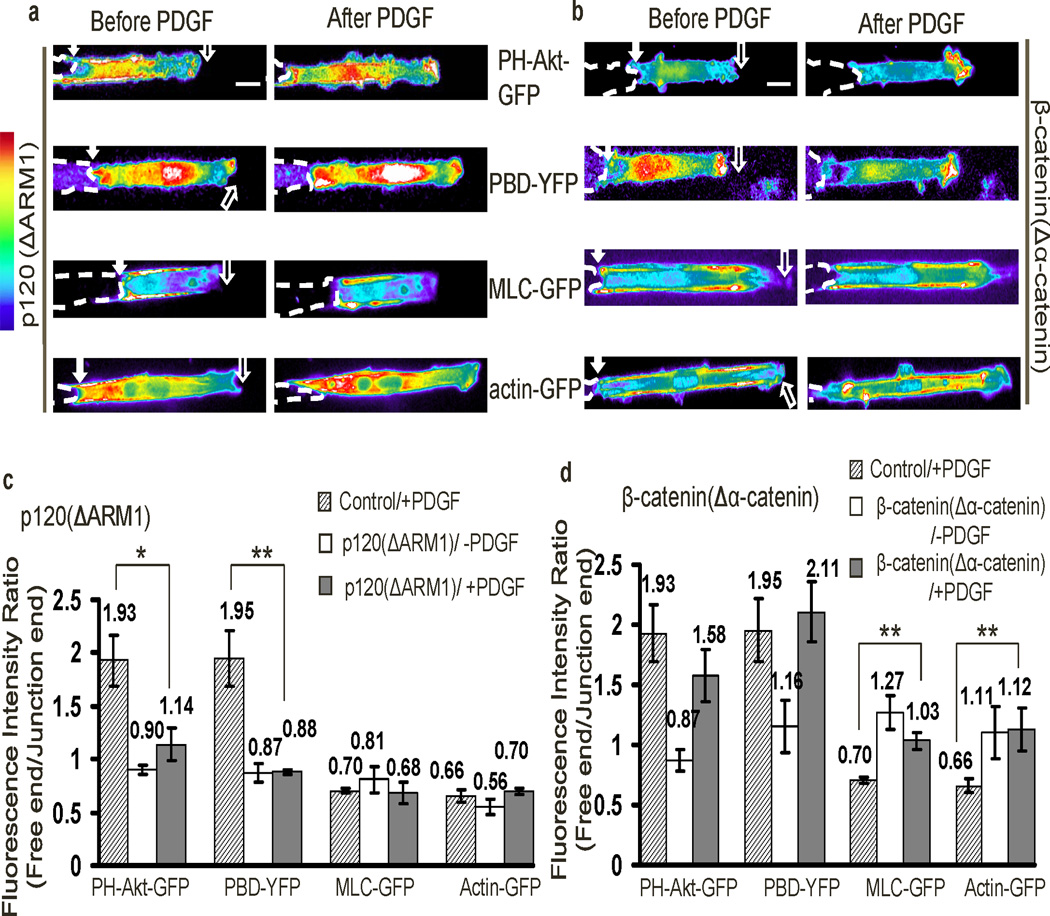

The above results suggested that N-cadherin–p120ctn complexes may suppress junctional PI3K and Rac activities, whereas N-cadherin– β-catenin complexes promote accumulation of MLC and AF near junctions. To further test these hypotheses, we expressed dominant negative mutants of p120ctn and β-catenin12,15. P120(ΔARM1), a mutant of p120ctn that lacks the armadillo repeat necessary for binding to N-cadherin15, impaired the junctional localization of endogenous p120ctn, but not β-catenin (Supplementary Fig. S11b). This construct did not affect MLC or AF, but suppressed polarization of PI3K and Rac, leading to high activity at both ends (Fig. 4a and 4c). We also expressed β-catenin(Δα-catenin), which does not bind to α-catenin12 or affect the junctional localization of p120ctn (Supplementary Fig. S11b). Consistent with the results of N-Cad(Δβ-catenin), β-catenin(Δα-catenin) abolished the polarity of MLC and AF, but not PI3K or Rac activity (Fig. 4b and 4d). Averaging fluorescence intensity along from multiple cells confirmed these effects (Supplementary Fig. S14). We also examined a second β-catenin mutant, β-catenin(ΔN-cad) which does not bind to N-cadherin42. However, expression of this construct blocked N-cadherin localization and all the downstream functions (Supplementary Fig. S15), possibly by suppressing the transcription and expression of N-cadherin42. Together, these results confirmed that the polarization of PI3K/Rac and MLC/AF is mediated by the N-cadherin–p120ctn and N-cadherin–β-catenin complexes, respectively.

Figure 4. The binding of p120ctn and β-catenin to N-cadherin regulates polarity.

(a–b) The intensity images of the fluorescent probes PH-Akt-GFP, PBD-YFP, MLC-GFP, or actin-GFP in MEFs co-transfected with (a) p120(ΔARM1) or (b) β-catenin(Δα-catenin). (c) and (d): The bar graphs (mean ± SEM, n=6, 5, 5, 6 for groups of a, and 5, 6, 5, 6 for groups of b, respectively. Student’s t-test, * represents P<0.05 and ** P<0.01) represent the fluorescence intensity ratios (free/junction) of different probes in cell groups shown in (a) and (b), respectively. (Scale bars, 10 µm)

Integrin signaling mediates the polarity of PI3K and Rac activities

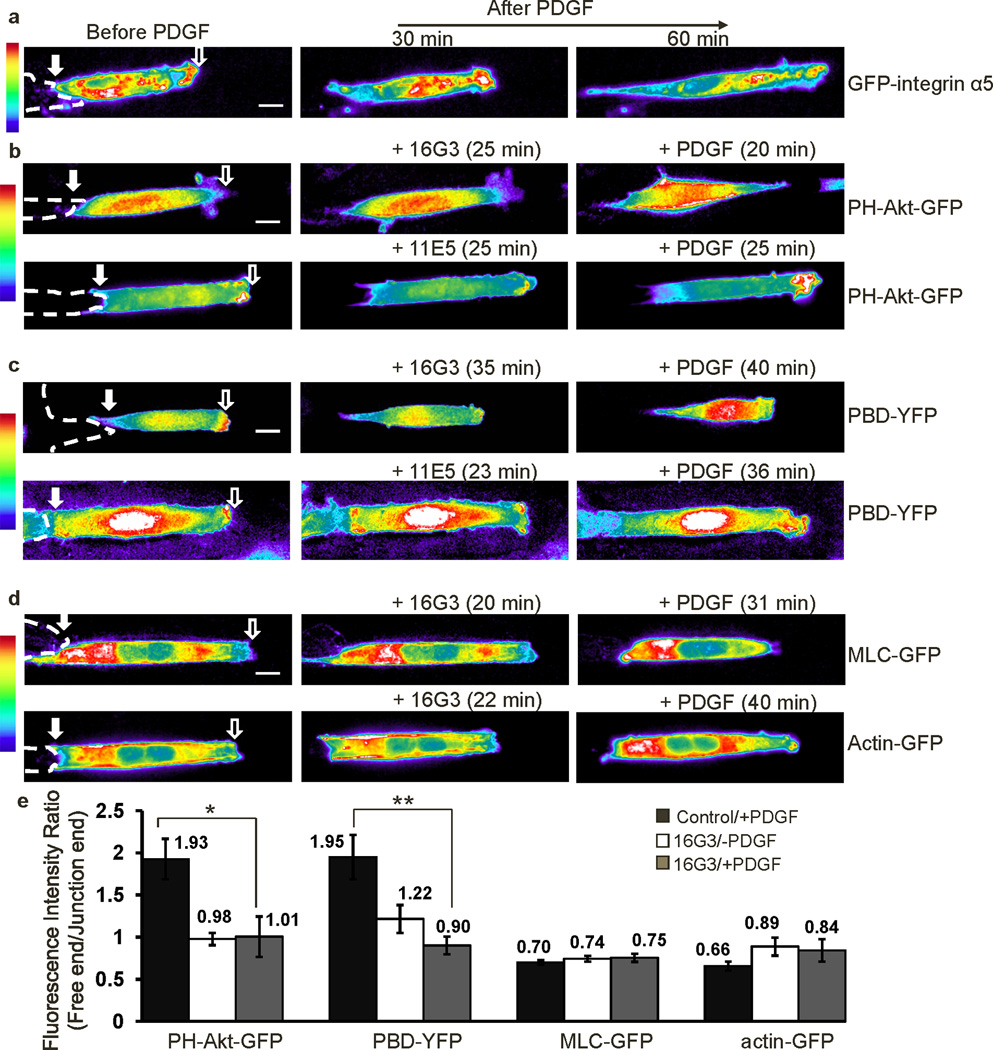

Binding of integrins to their ligands can activate Rac 8,9,43. We therefore examined the role of integrins in our system. GFP-conjugated integrin α5 was clearly polarized before and after PDGF stimulation, with a higher concentration at the free end (Fig. 5a, and Supplementary Movie 9). An antibody, 16G3, that binds fibronectin (Fn) and blocks integrin binding44, completely inhibited the high PI3K and Rac activities at the free end, whereas the non-blocking Fn antibody 11E5 had no effect (Figs. 5b–c, and e). 16G3, however, did not affect MLC or AF (Figs. 5d and e), suggesting that integrin signals specifically regulate PI3K and Rac. We also observed that Rac and PI3K activities were enhanced at the free end upon addition of MnCl2 (Supplementary Fig. S16), which directly activates integrins45. This result is consistent with the polarized integrin localization at the free end (Fig. 5a). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that integrins mediate the polarity of Rac and PI3K activities.

Figure 5. Integrins mediate the polarity of PI3K and Rac activities.

(a) The fluorescence intensity images of GFP-integrin α5 in a micropatterned MEF cell before and after PDGF stimulation. (b–c) The fluorescence intensity images of (b) PH-Akt-GFP or (c) PBD-YFP before and after the treatment with an Fn blocking antibody 16G3 (+16G3) or a control non-blocking antibody 11E5 (+11E5) prior to the PDGF stimulation (+PDGF). (d) The fluorescence intensity images of the probe MLC-GFP or actin-GFP before and after the treatment with an Fn blocking antibody 16G3 prior to the PDGF stimulation. (e) The bar graphs (mean ± SEM, n=4–6, Student’s t-test, * represents P<0.05 and ** P<0.01) show the fluorescence intensity ratios (free/junction) of the indicated probes with or without 16G3 pre-treatment followed by PDGF stimulation. (Scale bars, 10 µm)

Since integrins accumulate at the free end before PDGF stimulation (Fig. 5a) whereas the polarization of PI3K activity occurred mostly after PDGF (Fig. 1a–c), the polarity of PI3K activity may require the synergistic action of PDGFR and integrins. Interestingly, PDGFR also accumulated at the free end only after PDGF stimulation (Supplementary Fig. S17a). The polarized Rac activity in the absence of PDGF, on the contrary, may be directly promoted by the dynamic integrin ligation at the free end (Fig. 1d–f). Indeed, basal Rac polarity was abolished by the fibronectin blocking antibody 16G3, but not by the non-blocking antibody 11E5 (Supplementary Fig. S17b). These results suggest that the activation of PI3K at the free end requires both integrins and PDGFR, whereas Rac can have substantial basal activation by integrins only, which can be further augmented by PDGFR.

The N-cadherin–p120ctn axis suppresses integrins at the junction

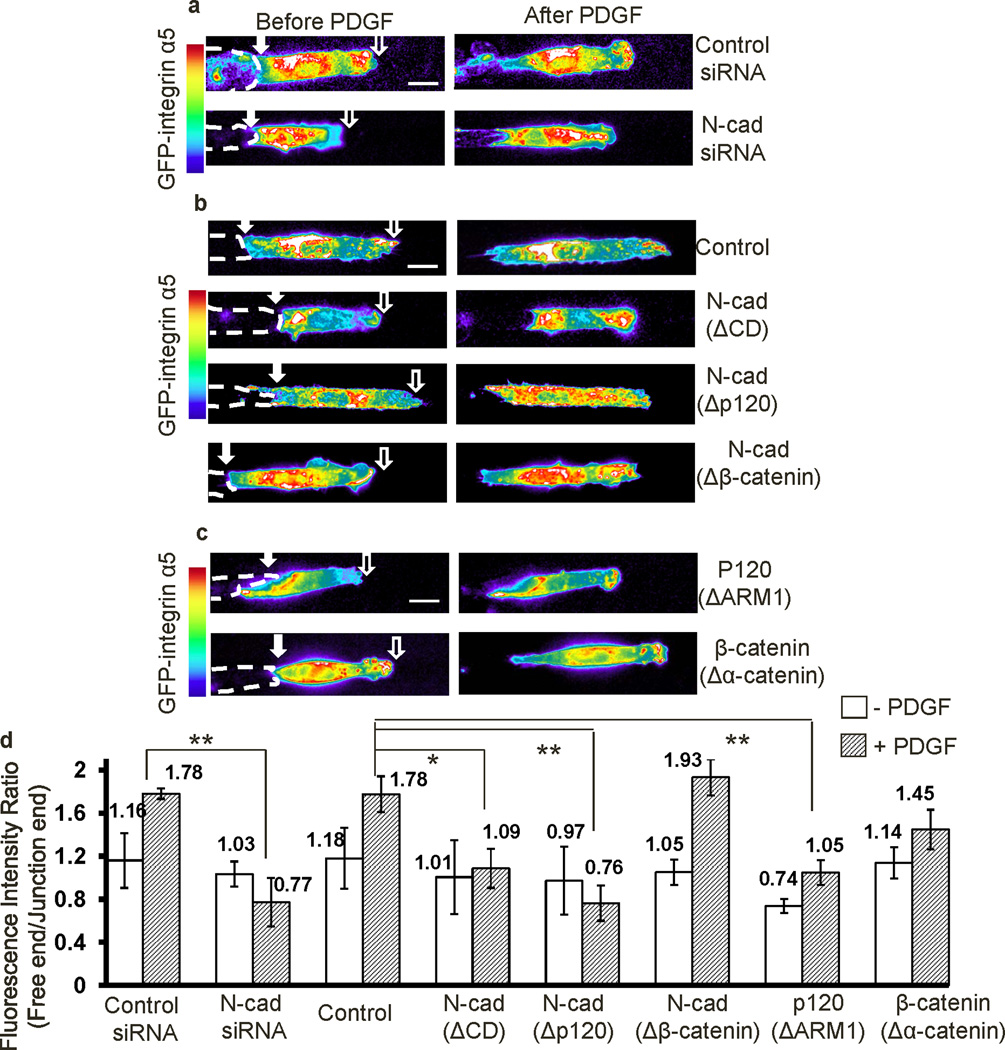

We next asked whether the N-cadherin–p120ctn axis regulates integrins to control the polarization of PI3K/Rac activities. Knockdown of N-cadherin by siRNA or the expression of N-cad(ΔCD) resulted in accumulation of GFP-integrin α5 at both the free and junction ends (Fig. 6a–b). Expression of N-cad(Δp120), but not N-cad(Δβ-catenin), also increased integrin α5 at junctions (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Movie 10). These results suggest that the association of p120ctn with N-cadherin may suppress the activation or trafficking of α5 integrin at cell-cell junctions. Consistent with this idea, GFP-integrin α5 localized at junctions in cells expressing p120(ΔARM1), but not in cells expressing β-catenin(Δα-catenin) (Fig. 6c). The ratio of integrin α5 intensity between the free and junction ends and the averaged curves of integrin α5-GFP fluorescence signal along the cell length confirmed that N-cadherin siRNA, N-cad(ΔCD), N-cad(Δp120), or p120(ΔARM1) induced integrin α5 accumulation at junctions whereas N-cad(Δβ-catenin) and β-catenin(Δα-catenin) had no effect (Fig. 6d, and Supplementary Fig. S18). Multiple independent results therefore support the conclusion that N-cadherin coupling to p120ctn blocks integrin function near cell-cell junctions.

Figure 6. The N-cadherin–p120ctn axis suppresses integrins at the junction.

(a) The fluorescence intensity images of GFP-integrin α5 co-transfected with control siRNA (50 nM) (n=4) or N-cadherin siRNA (50 nM) (n=4) before and after PDGF stimulation. (b–c) The fluorescence intensity images of GFP-integrin α5 in cells co-transfected with empty control vector (n=5), N-cad(ΔCD) (n=5), N-cad(Δp120) (n=4), N-cad(Δβ-catenin) (n=4), p120(ΔARM1) (n=4), or β-catenin(Δα-catenin) (n=5) before and after PDGF stimulation. (d) The bar graphs (mean ± SEM, n=4 or 5, Student’s t-test, * represents P<0.05 and ** P<0.01) show the fluorescence intensity ratios (free/junction) of GFP-integrin α5 in MEFs under the conditions in (a–c). (Scale bars, 10 µm)

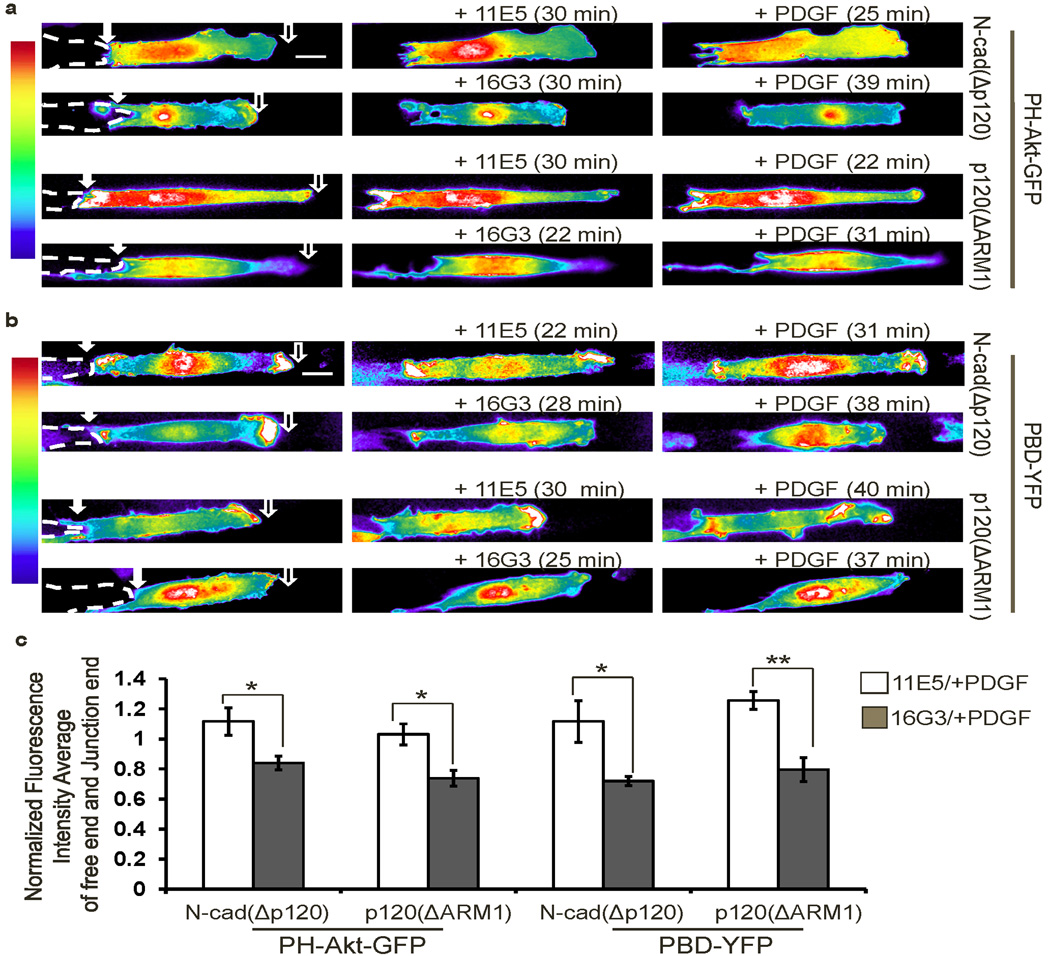

We then investigated whether integrin dynamics control the polarity of PI3K and Rac downstream of N-cadherin/p120ctn. The accumulation of PI3K activity at both the junction and the free end in cells expressing N-cad(Δp120) or p120(ΔARM1) was inhibited by 16G3, but not by 11E5 (Fig. 7a and c). Similarly, 16G3 blocked Rac activation at both ends in cells expressing N-cad(Δp120) or p120(ΔARM1) (Fig. 7b and c). These results confirmed that the N-cadherin-p120ctn axis suppresses integrins at the junction to inhibit PI3K and Rac.

Figure 7. The N-cadherin–p120ctn axis suppresses PI3K and Rac activities via integrins.

The fluorescence intensity images of the probe (a) PH-Akt-GFP or (b) PBD-YFP in MEFs co-transfected with either N-cad(Δp120) or p120(ΔARM1) before and after the treatment with an Fn blocking antibody 16G3 (+16G3) or a control non-blocking antibody 11E5 (+11E5) prior to the PDGF stimulation (+PDGF). (c) The bar graphs (mean ± SEM, n=4–6, Student’s t-test, * represents P<0.05 and ** P<0.01) show the normalized fluorescence intensity averages of free and junction ends of PH-Akt-GFP and PBD-YFP in MEFs after PDGF stimulation, with 11E5 or 16G3 pre-treatment, for experiments shown in a and b (seen Methods for details of quantification). (Scale bars, 10 µm)

Discussion

Subcellular polarity of signaling pathways is crucial for multiple cellular functions, including cell migration, tissue morphogenesis and cancer invasion2. To mimic collective cell migration in vivo, we established a model system, which avoids the damage of cells at the wounded edge and the subsequent release of chemical stimuli, as well as the debris remained in the wounded area. This model system also allows the convenient projection of molecular signals in one dimension, which facilitates statistical analysis and comparison among different cells. The ECM-coated strips constrain cell polarity movement to one dimension, thus facilitating analyses. Similar model systems utilizing micropatterning techniques have been successfully employed to demonstrate that the cell-cell adhesions can cause polarized cell morphology and centrosome distributions 18,19.

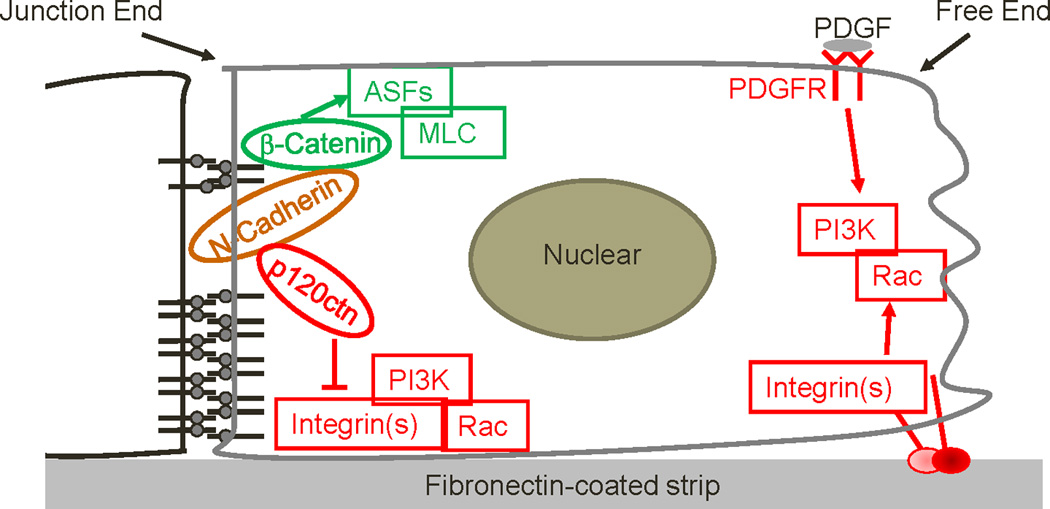

In this model system, the activities of PI3K and Rac concentrated at the free end of the cells, whereas MLC and AF accumulated near the junctional end. Polarity of PI3K and Rac depended on the N-cadherin-p120ctn complex, which acted by suppressing integrin function at the junctional end. By contrast, polarity of MLC and AF required the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex. These results therefore identify an integrated molecular network by which N-cadherin coordinates the subcellular polarity of different signaling molecules/activities through distinct effectors (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Mechanism of adherens junction complex in regulating molecular polarity.

A schematic diagram depicting the mechanism by which the N-cadherin–p120ctn and N-cadherin-β-catenin complexes differentially regulate the polarity of PI3K/Rac activities and MLC/AF distributions. Green indicates pathways that regulate MLC and AF; red indicates pathways that regulate PI3K and Rac.

Although E-cadherin is well known to induce PI3K/Rac activation during the formation of cell-cell junctions46,47, we found that stable N-cadherin junctions inhibited PI3K/Rac. This inhibitory effect of N-cadherin is consistent with previous reports18–20,48,49. We also found that the inhibition is mediated by local suppression of integrins through p120ctn. It has been reported that p120ctn can associate with E-cadherin to prevent the recruitment and activation of Rap1, which is an activator of the integrin functions26. Thus, the N-cadherin-p120ctn complex may also locally inhibit integrin activity through this pathway.

Our data further suggest that high PI3K and Rac activities at the free end involve cooperation between integrins and PDGFR. Activated integrins have been shown to associate and co-localize with PDGFR at the leading edge of migrating cells and to promote PDGFR activation50. Consistent with these results, we found that integrin ligation specifically promoted PDGFR activation at the free end upon PDGF stimulation. Integrin ligation can also directly recruit and activate Rac at membrane lipid rafts9,43 to mediate basal Rac activation and polarization. After addition of PDGF, integrins induce polarized activation of PDGFR, which recruits and activates PI3K to further activate Rac. Polarized integrin activity thereby appears to drive polarized Rac activation through both direct and indirect mechanisms. These “push and pull” effects at the two ends of the cell hence result in the polarity of PI3K and Rac activities upon PDGF stimulation.

MLC and AF concentrated at the two parallel edges near the junction. The arrangement of MLC depends on the acto-myosin contractility (Supplementary Fig. S5)51, likely due to high Rho activity in this region14,15,32,52. Our results show that β-catenin bound to N-cadherin mediates this polarity. To what extent β-catenin physically anchors actin filaments at these sites through α-catenin or other linkers, as opposed to controlling Rho activity through GEFs or GAPs, remains to be determined.

Immunofluorescence with an N-cadherin antibody against its cytosolic tail suggests that exogenous N-cad(ΔCD) expression in cells displaced endogenous N-cadherin from the junctions (Supplementary Fig. S10). Expression of exogenous N-cadherin, p120ctn, or β-catenin mutants specifically impaired the junctional localization of their target catenins but had minimal non-specific effect on other components (Supplementary Fig. S11a–b). Although the β-catenin-binding-domain in the cytoplasmic tail of E-cadherin is reportedly important for functional cell-cell adhesion and junctional localization53,54, other cadherins behave differently. For N-cadherin, the lack of catenin-binding-domain in the cytoplasmic tail does not prohibit the correct localization40. VE-cadherin with a truncated cytoplasmic tail also localized at cell-cell junctions39. Our results that N-cadherin mutants deficient in either p120 or β-catenin binding still localized to junctions (Supplementary Figs. S9d, and S11a) is therefore consistent with several previous reports.

The contours of neighboring cells physically contacting the cell of interest indicate that the knockdown of N-cadherin by siRNA or the expression of N-cadherin/catenin mutants did not significantly affect the contact areas among neighboring MEFs on the micropatterned Fn strips. It is possible that the physical cell-cell contacts between neighboring cells were maintained by other receptors such as JAMs or nectins despite impaired N-cadherin function as cells were constrained on the Fn-coated strips. Therefore, our model system can allow the study of cadherin/catenin functions in regulating molecular polarity without the disruption of physical cell-cell contacts.

In summary, our study presents evidence that cell-cell junctions determine the molecular polarity through a network of downstream effectors that independently control Rac and PI3K at the free edge, and actin and myosin at the junctional side. Surprisingly, the effect on Rac and PI3K is mediated by local control of integrins, which regulate both basal and PDGF-induced activities. These interlocking mechanisms are likely to determine collective cell migration in development, wound healing, cancer and other settings.

Methods

Gene construction and DNA plasmids

The cDNAs of N-cadherin and its truncated mutants were amplified from GFP-fused chicken N-cadherin construct55 and fused with a HA tag (hemagglutinin epitope tag YPYDVPDYA) at the C-terminus by PCR before being cloned into pcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen) for mammalian cell expression (Supplementary Fig. S8b). The full-length N-cadherin cDNA or its mutant N-Cad(ΔCD) with the intracellular tail truncated (aa 1–759) was amplified by PCR with a sense primer containing a NotI site and a Kozak sequence GCCACC before the start codon of ATG, and a reverse primer containing the sequence coding a HA tag, a stop codon, and an XbaI site. For N-cad(Δp120) or N-cad(Δβ-catenin), two cDNA fragments of N-cadherin with amino acid sequences 1–759 and 813–912, or 1–839 and 863–912 were amplified by PCR and fused together via a SphI site, respectively. All these PCR products were then cloned into pcDNA3.1 using the NotI/XbaI sites.

The mouse full-length p120ctn and its mutant p120(ΔARM1) with the ARM1 domain (aa 358–400) truncated were both directly amplified by PCR from the retroviral constructs LZRS-mp120-1A and LZRS-mp120 1A(ΔARM1)56 with a sense primer containing a EcoRI site, a Kozak sequence GCCACC, and a reverse primer containing a sequence coding the c-Myc epitope tag (EQKLISEEDL), a stop codon and a NotI site. The PCR products were cloned into pcDNA3.1 vector using the EcoRI/NotI sites.

The cDNAs of β-catenin and its truncated mutant were amplified by PCR from a GFP-fused Xenopus β-catenin construct kindly provided by Dr. Robert M. Kypta (MRC laboratory for Molecular Cell biology, University College, London) and fused with the c-Myc tag at the C-terminus before being cloned into pcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen). The full-length β-catenin cDNA (aa 1–781) was amplified by PCR with a sense primer containing a BamHI site and a Kozak sequence GCCACC, and a reverse primer containing the sequence coding c-Myc tag, a stop codon, and an NotI site. For β-catenin(Δα-catenin), two cDNA fragments of β-catenin with amino acid sequences 1–117 and 149–781 were amplified by PCR and fused together via a EcoRI site, respectively.

To construct mCherry plasmid, mCherry cDNA was directly digested out from MT1-MMP-mCherry previously described57 by using EcoRI/XhoI sites and ligated back into pcDNA3.1 using the same digestion sites. The construct of PDGFR-GFP is a kind gift from Dr. Hamid Band (Eppley Institute for Research in Cancer and Allied Diseases, University of Nebraska Medical Center). The constructs of PH-Akt-GFP, PAK-PBD-YFP, and N-cadherin-GFP (GFP-fused chicken N-cadherin) were kindly provided by Drs. Tamas Balla (National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health), Klaus Hahn (Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill), and Andre Sobel (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Unité Mixte de Recherche, France).

Microscope, image acquisition, and analysis

Cells expressing various exogenous proteins were starved in cell culture medium with 0.5% FBS for 36–48 hr before being passed on fibronectin-coated micropatterns generated atop cover-glass-bottom dishes (Cell E&G). During imaging, the cells were maintained in CO2-independent medium (Gibco BRL) without serum at 37°C. Images were collected by a Zeiss axiovert inverted microscope equipped with 40x objective and a cooled charge-coupled device camera (Cascade 512B; Photometrics) using the MetaFluor 6.2 software (Universal Imaging). The parameters of dichroic mirrors, excitation and emission filters for different fluorescent proteins were described previously58. Results were highly consistent among different cells, thus, 4–5 cells were analyzed for each condition to provide sufficient data for statistical analysis. The polarized signals were highly stable at 20–40 min after PDGF stimulation, therefore randomly selected representative fluorescent images from this time period were used for the quantification of molecular polarity (Figs. 1a–l and Supplementary Movies 2–4).

For the images analysis and polarity measurement, we have developed an automatic and objective procedure to quantify the polarized localization of fluorescent probes relative to the junction end59. All the fluorescence images were background-subtracted before quantification. The cell shapes were detected by segmenting the fluorescence intensity images using the Otsu’s method60 and converted into binary mask images with values outside the cell set to zero. In order to analyze the data from different cells in a uniform framework, the masks and corresponding cell images were rotated so that the micro-patterned strips were oriented horizontally, with the junction localized at the left side of the cell (Supplementary Fig. S2). The cell lengths were normalized to unity in the x-direction (strip or horizontal direction). For each individual cell, the fluorescence intensity within the cell mask along the x-direction was projected and averaged in the y-direction (perpendicular to the strip direction), and the averaged intensity curve was normalized by the whole-cell intensity and plotted against the normalized distance to the junction end (Supplementary Fig. S2). As such, the normalized intensity curves from different cells can be plotted within a uniform framework to allow the precise comparison between different groups. The averaged intensities in the x-direction from multiple cells with the same experimental condition were calculated and an average curve was then created using MATLAB function smooth (Mathworks; Natick, MA) by filtering with locally quadratic regression utilizing a moving window of size 5 (Supplementary Fig. S3). The overall behavior of each group of multiple cells can then be represented by one single curve.

To quantify the polarity of the fluorescence distribution, individual normalized intensity curves were smoothed using a weighted average within a moving window of 10% cell length (implemented with the MATLAB function ‘smooth’ with the ‘rloess’ option and ‘span = 0.1’) (Supplementary Fig. S2c). Then the ratios of maximum values on the smoothed curve near the free end (between 0.75 and 1) and the junction (between 0 and 0.25) for each individual cell were calculated. Since there was a substantial pool of GFP-integrin α5 accumulated around perinuclear regions, possibly reflecting those stored in the endo/exocytosis recycling route before being transported to the plasma membrane, the maximum intensity values of GFP-integrin α5 were selected on the smooth curves between 0 and 0.1 near the junction and between 0.9 and 1 near the free end to reduce the noise originated from the perinuclear integrin pool. The mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) of the polarity ratio in each group were calculated for comparison and analysis.

To quantify the ratio between the probe and mCherry, the intensity curves were calculated in individual cells and collectively smoothed among all cells with the moving average method as described above. The ratio between the smoothed curve of probe intensity and that of mCherry intensity was then calculated.

To quantify the effect of FN antibodies 11E5 or 16G3 on the accumulation of PI3K or Rac1 activity at both the junction and the free end in cells expressing N-cad(Δp120) or p120(ΔARM1), as shown in Figure 7, the average of maximal values on the smoothed normalized intensity curves near the free end (between 0.9 and 1) and the junction (between 0 and 0.1) for each individual cell were calculated. Note individual intensity curves were already normalized by whole-cell intensity, so this measurement should be independent of the expression level of the fluorescence probe in each cell (Supplementary Fig. S2). Statistics were analyzed with the two-tailed Student’s t-test, with p-values less than 0.05 indicating significance.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Cell culture reagents were obtained from GIBCO BRL. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (from ATCC), Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, and CHO cells expressing exogenous N-cadherin (N-CHO) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 unit/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate in a humidified 95% air, 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C before experiments.

Different DNA plasmids and siRNA were transfected into cells by using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manual protocol (Invitrogen). The co-transfection condition was optimized for MEFs, with 3 µg of DNA for each plasmid in each 35 mm cell culture dish.

Reagents

Recombinant rat platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB, 50 ng/ml), and myosin light chain (MLC) kinase (MLCK) inhibitor ML-7 (5 µM) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; PI3K inhibitor LY 294002 (10 µM) and Src inhibitor PP1 (10 µM) were purchased from Calbiochem and EMD Bioscience, respectively. ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool N-cadherin siRNA (N-cadherin siRNA) and ON-TARGETplus Non-Targeting siRNA (control siRNA) were purchased from Dharmacon RNAi technologies, Thermo Scientific. Anti-fibronectin antibodies 16G3 (20 µg/ml) and 11E5 (20 µg/ml) were previously described44. Mouse monoclonal p120 antibody, mouse monoclonal β-catenin antibody and mouse N-cadherin antibody were purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories. N-Cadherin-neutralizing antibody (GC-4) was from Sigma-Aldrich. Mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody, rabbit anti-c-Myc and anti-HA antibodies, mouse anti-tubulin antibody, and goat anti-NADPH antibody were from Santa Cruz Biotech. Goat FITC-conjugated anti-mouse and TRITC-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch.

Methods for Micropatterning, Immunofluorescence, Immunoprecipitation (IP) and Immunoblotting (IB) can be found in the supplementary information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants NIH HL098472, HL109142, NSF CBET0846429 (Y.W.), and NIH GM47214 (M.A. Schwartz).

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: Y.W., M.A.S, M.O., S.L., D.E.L, designed research; M.O., T.K., J.S. performed experiments; S.L. developed programs for data quantification; S.L., C-E.C., M.O. analyzed data; D.E.L., F.W., A.B.R. contributed additional reagents; Y.W., M.O., M.A.S., S.L., D.E.L., wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Moissoglu K, Schwartz MA. Integrin signalling in directed cell migration. Biol Cell. 2006;98:547–555. doi: 10.1042/BC20060025. doi:BC20060025 [pii] 10.1042/BC20060025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ridley AJ, et al. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302:1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. doi:10.1126/science.1092053 302/5651/1704 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raftopoulou M, Hall A. Cell migration: Rho GTPases lead the way. Dev Biol. 2004;265:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.06.003. doi:S001216060300544X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han J, et al. Role of substrates and products of PI 3-kinase in regulating activation of Rac-related guanosine triphosphatases by Vav. Science. 1998;279:558–560. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michiels F, et al. Regulated membrane localization of Tiam1, mediated by the NH2-terminal pleckstrin homology domain, is required for Rac-dependent membrane ruffling and C-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:387–398. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bokoch GM, Vlahos CJ, Wang Y, Knaus UG, Traynor-Kaplan AE. Rac GTPase interacts specifically with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. The Biochemical journal. 1996;315(Pt 3):775–779. doi: 10.1042/bj3150775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balasubramanian N, Scott DW, Castle JD, Casanova JE, Schwartz MA. Arf6 and microtubules in adhesion-dependent trafficking of lipid rafts. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1381–1391. doi: 10.1038/ncb1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishiya N, Kiosses WB, Han J, Ginsberg MH. An alpha4 integrin-paxillin-Arf-GAP complex restricts Rac activation to the leading edge of migrating cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:343–352. doi: 10.1038/ncb1234. doi:ncb1234 [pii] 10.1038/ncb1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.del Pozo MA, et al. Integrins regulate Rac targeting by internalization of membrane domains. Science. 2004;303:839–842. doi: 10.1126/science.1092571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu J, et al. Divergent signals and cytoskeletal assemblies regulate self-organizing polarity in neutrophils. Cell. 2003;114:201–214. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00555-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ilina O, Friedl P. Mechanisms of collective cell migration at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3203–3208. doi: 10.1242/jcs.036525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pokutta S, Weis WI. Structure and mechanism of cadherins and catenins in cell-cell contacts. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:237–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104241. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anastasiadis PZ, Reynolds AB. Regulation of Rho GTPases by p120-catenin. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:604–610. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noren NK, Liu BP, Burridge K, Kreft B. p120 catenin regulates the actin cytoskeleton via Rho family GTPases. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:567–580. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wildenberg GA, et al. p120-catenin and p190RhoGAP regulate cell-cell adhesion by coordinating antagonism between Rac and Rho. Cell. 2006;127:1027–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabatini PJ, Zhang M, Silverman-Gavrila R, Bendeck MP, Langille BL. Homotypic and endothelial cell adhesions via N-cadherin determine polarity and regulate migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2008;103:405–412. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qin Y, Capaldo C, Gumbiner BM, Macara IG. The mammalian Scribble polarity protein regulates epithelial cell adhesion and migration through E-cadherin. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:1061–1071. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506094. doi:jcb.200506094 [pii] 10.1083/jcb.200506094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desai RA, Gao L, Raghavan S, Liu WF, Chen CS. Cell polarity triggered by cell-cell adhesion via E-cadherin. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:905–911. doi: 10.1242/jcs.028183. doi:10.1242/jcs.028183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupin I, Camand E, Etienne-Manneville S. Classical cadherins control nucleus and centrosome position and cell polarity. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:779–786. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200812034. doi:10.1083/jcb.200812034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Theveneau E, et al. Collective chemotaxis requires contact-dependent cell polarity. Developmental cell. 2010;19:39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.012. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, et al. Integrins regulate VE-cadherin and catenins: dependence of this regulation on Src, but not on Ras. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1774–1779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510774103. doi:0510774103 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0510774103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Rooij J, Kerstens A, Danuser G, Schwartz MA, Waterman-Storer CM. Integrin-dependent actomyosin contraction regulates epithelial cell scattering. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:153–164. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Gumbiner BM. Crosstalk between different adhesion molecules. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.07.002. doi:S0955-0674(06)00110-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arregui C, Pathre P, Lilien J, Balsamo J. The nonreceptor tyrosine kinase fer mediates cross-talk between N-cadherin and beta1-integrins. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1263–1274. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.6.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lilien J, Arregui C, Li H, Balsamo J. The juxtamembrane domain of cadherin regulates integrin-mediated adhesion and neurite outgrowth. J Neurosci Res. 1999;58:727–734. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19991215)58:6<727::aid-jnr1>3.0.co;2-7. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19991215)58:6<727::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balzac F, et al. E-cadherin endocytosis regulates the activity of Rap1: a traffic light GTPase at the crossroads between cadherin and integrin function. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4765–4783. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lehembre F, et al. NCAM-induced focal adhesion assembly: a functional switch upon loss of E-cadherin. EMBO J. 2008;27:2603–2615. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.178. doi:emboj2008178 [pii] 10.1038/emboj.2008.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tzima E, et al. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature. 2005;437:426–431. doi: 10.1038/nature03952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balla T, Varnai P. Visualizing cellular phosphoinositide pools with GFP-fused protein-modules. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:pl3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.125.pl3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srinivasan S, et al. Rac and Cdc42 play distinct roles in regulating PI(3,4,5)P3 and polarity during neutrophil chemotaxis. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:375–385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208179. doi:10.1083/jcb.200208179 jcb.200208179 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ward Y, et al. The GTP binding proteins Gem and Rad are negative regulators of the Rho-Rho kinase pathway. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:291–302. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamada S, Nelson WJ. Localized zones of Rho and Rac activities drive initiation and expansion of epithelial cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:517–527. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nobes CD, Hall A. Rho, rac, and cdc42 GTPases regulate the assembly of multimolecular focal complexes associated with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia, and filopodia. Cell. 1995;81:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rullo J, et al. Actin polymerization stabilizes alpha4beta1 integrin anchors that mediate monocyte adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:115–129. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201107140. doi:10.1083/jcb.201107140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agiostratidou G, Hulit J, Phillips GR, Hazan RB. Differential cadherin expression: potential markers for epithelial to mesenchymal transformation during tumor progression. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia. 2007;12:127–133. doi: 10.1007/s10911-007-9044-6. doi:10.1007/s10911-007-9044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El Sayegh TY, et al. Cortactin associates with N-cadherin adhesions and mediates intercellular adhesion strengthening in fibroblasts. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5117–5131. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01385. doi:10.1242/jcs.01385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levenberg S, Yarden A, Kam Z, Geiger B. p27 is involved in N-cadherin-mediated contact inhibition of cell growth and S-phase entry. Oncogene. 1999;18:869–876. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goncharova EJ, Kam Z, Geiger B. The involvement of adherens junction components in myofibrillogenesis in cultured cardiac myocytes. Development. 1992;114:173–183. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kametani Y, Takeichi M. Basal-to-apical cadherin flow at cell junctions. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:92–98. doi: 10.1038/ncb1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kintner C. Regulation of embryonic cell adhesion by the cadherin cytoplasmic domain. Cell. 1992;69:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90404-z. doi:0092-8674(92)90404-Z [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sadot E, Simcha I, Shtutman M, Ben-Ze'ev A, Geiger B. Inhibition of beta-catenin-mediated transactivation by cadherin derivatives. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15339–15344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huber AH, Nelson WJ, Weis WI. Three-dimensional structure of the armadillo repeat region of beta-catenin. Cell. 1997;90:871–882. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80352-9. doi:S0092-8674(00)80352-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galbraith CG, Yamada KM, Sheetz MP. The relationship between force and focal complex development. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:695–705. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204153. doi:10.1083/jcb.200204153 jcb.200204153 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tzima E, del Pozo MA, Shattil SJ, Chien S, Schwartz MA. Activation of integrins in endothelial cells by fluid shear stress mediates Rho-dependent cytoskeletal alignment. EMBO J. 2001;20:4639–4647. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen J, Salas A, Springer TA. Bistable regulation of integrin adhesiveness by a bipolar metal ion cluster. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:995–1001. doi: 10.1038/nsb1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takaishi K, Sasaki T, Kotani H, Nishioka H, Takai Y. Regulation of cell-cell adhesion by rac and rho small G proteins in MDCK cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1047–1059. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.4.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rivard N. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase: a key regulator in adherens junction formation and function. Front Biosci. 2009;14:510–522. doi: 10.2741/3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Charrasse S, Meriane M, Comunale F, Blangy A, Gauthier-Rouviere C. N-cadherin-dependent cell-cell contact regulates Rho GTPases and beta-catenin localization in mouse C2C12 myoblasts. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:953–965. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hay E, Nouraud A, Marie PJ. N-cadherin negatively regulates osteoblast proliferation and survival by antagonizing Wnt, ERK and PI3K/Akt signalling. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schneller M, Vuori K, Ruoslahti E. Alphavbeta3 integrin associates with activated insulin and PDGFbeta receptors and potentiates the biological activity of PDGF. EMBO J. 1997;16:5600–5607. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smutny M, et al. Myosin II isoforms identify distinct functional modules that support integrity of the epithelial zonula adherens. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:696–702. doi: 10.1038/ncb2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeMali KA, Wennerberg K, Burridge K. Integrin signaling to the actin cytoskeleton. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:572–582. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nagafuchi A, Takeichi M. Cell binding function of E-cadherin is regulated by the cytoplasmic domain. EMBO J. 1988;7:3679–3684. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nagafuchi A, Takeichi M. Transmembrane control of cadherin-mediated cell adhesion: a 94 kDa protein functionally associated with a specific region of the cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin. Cell Regul. 1989;1:37–44. doi: 10.1091/mbc.1.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thoumine O, Lambert M, Mege RM, Choquet D. Regulation of N-cadherin dynamics at neuronal contacts by ligand binding and cytoskeletal coupling. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:862–875. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0335. doi:E05-04-0335 [pii] 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ireton RC, et al. A novel role for p120 catenin in E-cadherin function. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:465–476. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205115. doi:10.1083/jcb.200205115 jcb.200205115 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ouyang M, et al. Visualization of polarized membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase activity in live cells by fluorescence resonance energy transfer imaging. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17740–17748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709872200. doi:M709872200 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M709872200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ouyang M, Sun J, Chien S, Wang Y. Determination of hierarchical relationship of Src and Rac at subcellular locations with FRET biosensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14353–14358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807537105. doi:0807537105 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0807537105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu S, et al. Computational analysis of the spatiotemporal coordination of polarized PI3K and Rac1 activities in micro-patterned live cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021293. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Otsu N. A Threshold Selection Method from Gray-Level Histograms. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, Cybernetics. 1979;9:62–66. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.