Abstract

Leptin is a hormone secreted by adipocytes that plays a pivotal role in regulation of food intake, energy expenditure, and neuroendocrine function. Several lines of evidences indicate that independent of the anorexic effect, leptin regulates glucose and lipid metabolism in peripheral tissues in rodents and humans. It has been shown that leptin improves the diabetes phenotype in lipodystrophic patients and rodents. Moreover, leptin suppresses the development of severe, progressive impairment of glucose metabolism in insulin-deficient diabetes in rodents. We found that leptin increases glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle in rats and mice in vivo. Leptin increases glucose uptake in skeletal muscle via the hypothalamic–sympathetic nervous system axis and β-adrenergic mechanism, while leptin stimulates fatty acid oxidation in muscle via AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). Leptin-induced fatty acid oxidation results in the decrease of lipid accumulation in muscle, which can lead to functional impairments called as “lipotoxicity.” Activation of AMPK occurs by direct action of leptin on muscle and through the medial hypothalamus–sympathetic nervous system and α-adrenergic mechanism. Thus, leptin plays an important role in the regulation of glucose and fatty acid metabolism in skeletal muscle.

Keywords: AMP-activated protein kinase, hypothalamus, leptin, skeletal muscle, sympathetic nervous system

INTRODUCTION

Leptin is secreted by adipocytes and signals nutritional information to regulatory centers in the hypothalamus and other brain regions.[1] Treatment with the hormone in animals suppresses food intake and increases energy expenditure, accompanied by reduction in the amount of adipose tissue and intracellular lipid in skeletal muscle, liver, and pancreatic β-cells.[1–4] Decrease in the amount of lipid in these tissues is evident at doses that do not affect weight, suggesting that the effect of leptin is not only a consequence of its ability to reduce food intake.[5]

Skeletal muscle is a principal site of glucose and fatty acid utilization, and is one of the primary tissues responsible for insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes.[6] Increased lipid stores in nonadipose tissues, such as muscle are linked to functional impairments, called “lipotoxicity,” which lead to insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion.[2] Although the lipid factor that causes “lipotoxicity” is not identified, involvement of fatty acyl-CoA or diacylglycerol, acting through a form of protein kinase C, is suspected.[7] As well as in obesity, insulin resistance appears in lipodystrophy, in which fat tissue is absent.[8,9] In this rare human disorder, excess lipid accumulates in tissues such as the liver and skeletal muscle, and patients suffer from severe insulin-resistant diabetes. Genetically engineered experimental animals show the same pathophysiology.[10,11] It has been demonstrated that treatment with leptin decreases lipid accumulation in nonadipose tissues and improves severe diabetes in lipodystrophy patients as well as rodents.[5,8–10]

Recently, studies indicate that leptin suppresses the development of the impaired glucose metabolism in rodents treated with streptozotocin (STZ) and Akita mice with insulinopenia.[12–20] Hyperleptinemia induced by either pharmacologic leptin administration or with adenoviral infection, fully amieliorates hyperglycemia in those insulin-deficient animals, even in the extremely low plasma insulin levels. While this effect is partly due to the normalization of hyperphagia and circulating levels of glucagon and corticosterone, those cannot fully explain the improvement of STZ-induced diabetes in response to hyperleptinemia. Other regulatory mechanisms are necessary to supply energy and nutrients into skeletal muscle to improve the severe diabetes phenotype in the absence of insulin.

In this review, we focus on the regulatory roles of leptin in glucose and lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle. Our results suggest that leptin stimulates glucose uptake in skeletal muscle via the hypothalamic–sympathetic nervous system and β-adrenergic mechanism.[21–23] Furthermore, we demonstrate that leptin stimulates fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle via AMPK. Activation of AMPK occurs by direct action of leptin on muscle and through the medial hypothalamus-sympathetic nervous system and α-adrenergic mechanism.[24] Leptin-induced fatty acid oxidation results in the decrease of lipid accumulation in muscle, and suppresses functional impairments called as “lipotoxicity,” such as insulin resistance. Thus, leptin plays an important role in the regulation of glucose and fatty acid metabolism in skeletal muscle.

LEPTIN STIMULATES GLUCOSE UPTAKE IN SKELETAL MUSCLE VIA THE HYPOTHALAMIC–SYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

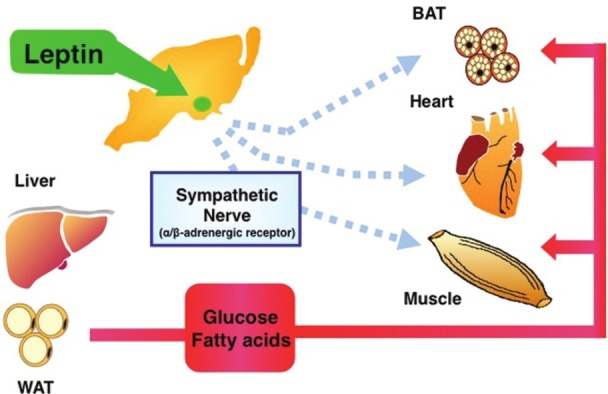

It is now evident that many of the effects of leptin on metabolism, as well as food intake, are exerted in the hypothalamus.[1,6] We and others have shown that injection of leptin into the medial hypothalamus, including ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMN) increases glucose uptake by skeletal muscle, brown adipose tissue (BAT), and heart but not in white adipose tissue (WAT) [Figure 1].[21–23,25] The effect of leptin can be observed acutely (6 h after the injection) and is independent of feeding behavior. In skeletal muscle, the effect of leptin was observed in red type of muscle, such as soleus muscle, rather than white type of muscle. Leptin has little effect on glucose uptake in skeletal muscle ex vivo. Although intracerebroventricular (icv) or intravenous (iv)injection of leptin normalizes blood glucose levels in insulin-deficient diabetic animals,[12–20] the leptin-induced glucose uptake is enhanced with insulin administration.[22] Thus, leptin stimulates glucose uptake in muscle in both insulin-dependent and -independent manner.

Figure 1.

Regulatory roles of hypothalamic leptin in glucose and fatty acid utilization in peripheral tissues. Leptin in the hypothalamus stimulates glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, heart, and BAT via the sympathetic nerve and β-adrenergic mechanism. In addition, leptin also stimulates fatty acid oxidation in those tissues. In skeletal muscle, leptin-induced fatty acid oxidation is activated via the sympathetic nerve-α-adrenergic receptor and muscle AMPK. Muscle AMPK is activated by direct action of leptin on muscle, as well as through the hypothalamus–sympathetic nervous system (see text)

Intravenous and icv injection of leptin stimulates sympathetic nerve activity in peripheral tissues.[26,27] A sympathetic nerve-blocking agent (guanethidine), a β-adrenergic antagonist (propranolol), and surgical sympathetic denervation blunt the leptin's action,[21,22] whereas the effect of leptin injection into the VMN on muscle glucose uptake is not blocked by adrenal demedulation. These results suggest that leptin increases glucose uptake in skeletal muscle via sympathetic nerve and β-adrenergic mechanism. In support of this, we recently reported that injection of a hypothalamic neuropeptide orexin into the VMN stimulates glucose uptake in muscle in mice, similar to that of leptin, via sympathetic nerve and β-adrenergic receptor.[28] The orexin-induced muscle glucose uptake was blunted in β-adrenergic receptors-deficient mice (β-less mice), while the expression of β2-adrenergic receptor in muscle in β-less mice recovered the orexin action in the tissue.

Studies with catecholamine administration have suggested that the sympathetic nervous system inhibits the insulin signaling pathway in peripheral tissues. However, our results show that the preferential stimulation of sympathetic nerves and subsequent signaling of β2-adrenergic receptor, which is a dominant type of β-adrenergic receptor, result in activation of the insulin signaling pathway in skeletal muscle in vivo. The effects of sympathetic nerves on muscle glucose metabolism may differ in some instances from those of catecholamine administration. Consistent with this notion, a β2-adrenergic receptor-specific agonist was previously shown to increase glucose uptake in L6 myocytes via activation of PI3-kinase, with this effect being inhibited by protein kinase A.[29] Thus, leptin increases glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle through the hypothalamic–sympathetic nervous system axis.

Leptin receptor Ob–Rb abundantly expresses in the hypothalamus, especially in the arcuate hypothalamic nucleus (ARC), VMN, and dorsomedial nucleus (DMN), with a lesser amount in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and lateral hypothalamic area (LHA).[1] The ARC contains two of the most well-characterized leptin-sensitive neuronal populations: one is the neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP)-coexpressing neurons, and another is the pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC)-expressing neurons. NPY and AgRP-coexpressing neurons release γ-amino butylic acid (GABA) and inhibit neuronal activity of POMC neurons in the ARC. NPY and AgRP stimulate food intake and inhibit energy expenditure. A product of POMC, α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH), is released in POMC neurons in the ARC and acts on melanocortin receptor (MCR) to suppress food intake and increase energy expenditure. Leptin activates POMC neurons and inhibits the activity of NPY/AgRP neurons in the ARC. It has been reported that leptin signaling in POMC neurons is important in the regulation of glucose metabolism. Expression of leptin receptors in POMC neurons in db/db mice, which lack functional leptin receptors, ameliorates hyperglycemia, hyperglucagonemia and dyslipidemia, whereas it modestly reduces body weight and hyperinsulinemia.[30]

The VMN neurons also play an important role in the leptin's action on glucose metabolism. As mentioned, preferential injection of leptin into the VMN enhances glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, heart, and BAT, but not in WAT.[21–23] Leptin rapidly increases the firing rate of steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1)-containing neurons in the nucleus, whereas selective deletion of leptin receptors of SF-1 neurons results in an obese, insulin-resistance phenotype.[31,32] Both SF-1 in the VMN and POMC in the ARC are necessary for the normal glucose metabolism. Severe insulin resistance occurs in mice that have neither leptin receptor in SF-1 nor POMC neurons.[31] Previous studies revealed that MCR agonist MT-II preferentially increases the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the VMN, whereas a subset of VMN neurons activates POMC neurons in the ARC.[33,34]

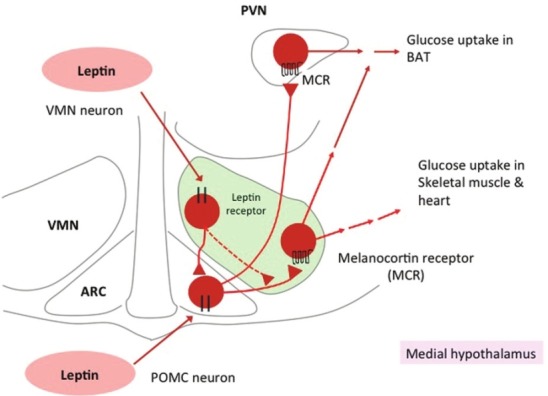

We recently explored the roles of the medial hypothalamic nuclei in leptin-induced glucose uptake in peripheral tissues.[23] Leptin injection into the VMN increased glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, BAT, and heart, whereas that into the ARC increased glucose uptake in BAT but not muscle or heart, and that into the DMN or PVN had no effect [Figure 2]. The icv MCR antagonist SHU9119 abolished the effects of leptin injected into the VMN on glucose uptake in muscle and other peripheral tissues.[23] Furthermore, injection of MCR agonist MT- II either into the VMN or intracerebroventricularly increased glucose uptake in muscle, BAT, and heart, whereas that into the PVN increased glucose uptake in BAT, and that into the DMN or ARC had no effect. Thus, the effect of leptin on muscle glucose uptake is dependent on MCR activation in the VMN, whereas the leptin receptor in the ARC and MCR in the PVN regulate glucose uptake in BAT.

Figure 2.

Distinct roles of the medial hypothalamic nuclei in leptin-induced glucose uptake in peripheral tissues.[23] Leptin activates VMN neurons as well as POMC neurons in the ARC, and then activates MCR in the VMN and PVN. Activation of MCR in the VMN stimulates glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, BAT, and heart, whereas that in the PVN increases glucose uptake in BAT

To identify the direct neuronal circuits whereby MCR regulates peripheral tissues, retrograde tracing studies with pseudorabies virus (PRV) were conducted in combination with in situ hybridization of melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R). Injection of PRV into interscapular BAT or WAT led to PRV co-labeling in MC4R-positive cells within hypothalamic nuclei, including the PVN, LHA, DMN, ARC, and VMN.[35,36] A recent study also used Ob-Rb-GFP reporter mice with muscle-specific injection of RFP-expressing PRV, and reported that PRV labeling is observed within these hypothalamic nuclei.[37] However, the study also indicated that significant number of double-labeled cells with Ob-Rb and PRV is found only in the brainstem nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and the hypothalamic retrochiasmatic area (Rch). Further studies are required to explore the role of NTS and Rch in leptin-induced muscle glucose uptake.

LEPTIN STIMULATES FATTY ACID OXIDATION IN SKELETAL MUSCLE BY ACTIVATING AMPK

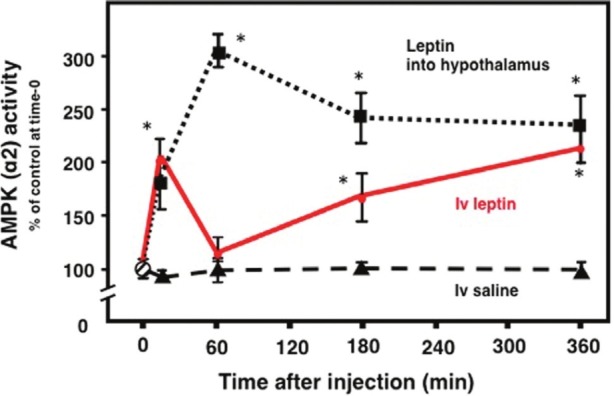

AMPK is a regulator of cellular metabolism in response to changes in the energy status of the cells.[38] It has been demonstrated that activation of AMPK participates in the contraction-induced glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation in muscle at least in part.[39] We examined AMPK activity in skeletal muscle after the medial hypothalamus and intravenous injection of leptin in mice.[24] Injection of leptin into the medial hypothalamus increased the activity of α2 AMPK in red type of skeletal muscle, such as soleus muscle. The effect peaked with a threefold stimulation at 1 h and was sustained for up to 6 h [Figure 3]. In contrast, iv leptin produced a biphasic response in α2 AMPK activity, with a twofold rise at about 15 min, a return to baseline by 60 min, and a second twofold elevation by 6 h. α1 AMPK activity did not change in soleus muscle after iv or ihp injection of leptin.

Figure 3.

Leptin activates α2 AMPK in soleus muscle.[24] α2 AMPK activity in soleus muscle after medial hypothalamic injection of leptin (1 ng) (squares, and dotted line) or intravenous injection of leptin (1 mg/kg) (iv, filled circle) or saline (triangles, and dashed line) in FVB male mice. *P< 0.05 compared with saline injection. (Source: Modifi ed from Minokoshi Y and Kahn BB. Biochem Soc Trans 2003;31:196–201.)

A lower dose of leptin, which is closer to the physiologic range, also stimulated AMPK activity in muscle at both 15 min and 6 h after injection.[24] Notably, db/db mice, which lack the long-form leptin receptor Ob-Rb did not show any stimulation of AMPK, even with high dose of leptin. Similar to the effect of leptin injection into the medial hypothalamus, the effect of iv leptin on the activation of α2 AMPK was more pronounced in red (slow twitch, oxidative) skeletal muscles,[24] which have higher rates of fatty acid oxidation, than in white (fast twitch, glycolytic) muscles. These results indicate that intravenous and medial hypothalamic injection of leptin activate α2 AMPK in red muscle through Ob-Rb.

We explored whether leptin-induced activation of AMPK in muscle is mediated by the sympathetic nervous system, using pharmacologic adrenergic blockade and two kinds of surgical denervation of hindlimb.[24] Denervation of the sciatic nerve, which primarily impairs motor innervation, decreased the total catecholamine content to 62% of the contralateral, intact soleus muscle. Denervation of the sciatic, femoral, and obturator nerves, which block both sympathetic and motor innervation, decreased catecholamine content to 6% of the control content.

Denervation of all three nerves blocked the ability of hypothalamic injection of leptin or iv leptin 6 h after injection to stimulate α2 AMPK in soleus muscle.[24] But AMPK activation at 15 min after iv leptin remained intact in denervated muscle. By contrast, denervation of the sciatic nerve alone did not block leptin-induced activation of AMPK in soleus, despite a complete loss of motor function.[24] Thus leptin's effect on AMPK is independent of motor nerve activity. These findings indicate that AMPK activation at 6 h after both iv leptin and hypothalamic injection of leptin may be mediated by the sympathetic nerves that innervate muscle. In support of the mechanism, peripheral leptin injection increases sympathetic nerve activity that innervates hindlimbs, with a time course that is consistent with the late activation of α2 AMPK in muscle after iv leptin.[27] In contrast, activation at 15 min after iv leptin does not involve the sympathetic nervous system and may be direct. Consistent with this, leptin increased α2 AMPK activity in soleus muscle ex vivo.[24] Thus, the early effect of iv leptin may be direct, but the latter effect depends on the sympathetic nerve innervating the muscle [Figures 3 and 4].

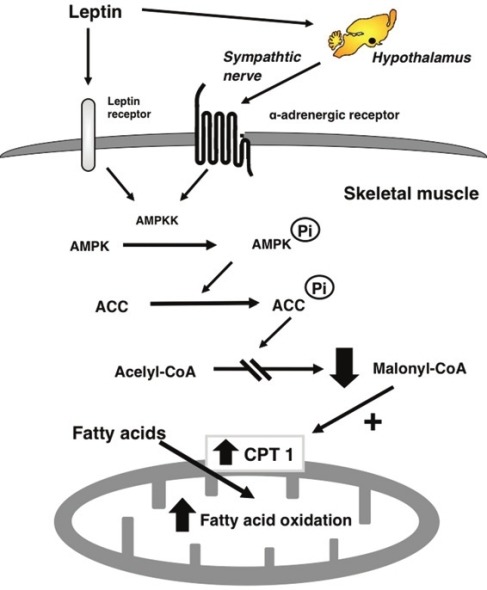

Figure 4.

Model for the stimulatory effect of leptin on fatty acid oxidation in muscle. Leptin activates AMPKK/AMPK in muscle through two distinct mechanisms: a direct effect of leptin and the hypothalamic–sympathetic nervous system and α-adrenergic receptor. Activation of AMPK phosphorylates and inhibits ACC activity. Leptin then inhibits malonyl CoA synthesis, activating CPT1, thereby increasing mitochondria import and fatty acid oxidation in muscle. (Source: Minokoshi Y and Kahn BB. Modified from Biochem Soc Trans 2003;31:196–201.)

Interestingly, our results revealed that the α-adrenergic receptor, but not β-adrenergic receptor, is involved in the sympathetic nerve-mediated effect of leptin on AMPK.[24] AMPK can be activated by the stimulation of Gq-coupled receptors, including α-adrenergic receptors.[40] Gq-coupled receptors stimulate intracellular calcium signaling and activate an AMPK kinase, calcium-/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase (CaMKK).[38] The involvement of CaMKK in the activation of muscle AMPK is suggested by the recent study showing that adiponectin activates AMPK in skeletal muscle via CaMKK by increasing cytosolic Ca2+-level.[41] Thus, AMPK activation is mediated by the α-adrenergic mechanism, whereas glucose uptake is mediated by β-adrenergic receptor. Similar to that of leptin-induced glucose uptake, MCR in the brain also involves the hypothalamic effect of leptin on muscle α2 AMPK. The icv MT-II injection activated muscle AMPK, whereas MCR antagonist blunted the leptin's effect.[42]

Acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) carboxylase (ACC), which is a target of AMPK, provides a pivotal step in fuel metabolism, as it links fatty acid and glucose metabolism through the shared intermediate acetyl-CoA [Figure 4].[43] Phosphorylation of ACC by AMPK leads to the inhibition of ACC activity, a fall in malonyl-CoA content, and a subsequent increase in fatty acid oxidation by disinhibiting carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) in skeletal muscle.[38,39,43] To determine whether AMPK activation mediates leptin's effects on fatty acid metabolism, we examined the activity of ACC.[24] Intravenous and hypothalamic injection of leptin suppressed ACC activity in soleus muscle.[24] These effects are probably caused by phosphorylation of ACC by AMPK, as ACC phosphorylation in soleus muscle increased after iv leptin, whereas concentrations of ACC protein did not change. ACC phosphorylation 6 h after iv leptin was blocked by surgical denervation of the sciatic, femoral, and obturator nerves. In db/db mice, leptin did not stimulate phosphorylation of AMPK or ACC. Moreover, leptin-induced ACC phosphorylation in cultured muscle cells expressing Ob-Rb, whereas the effect is suppressed with the expression of dominant-negative AMPK.

The decrease of ACC activity by leptin suggests that malonyl-CoA production is suppressed, leading to stimulation of fatty acid oxidation by disinhibition of carnitine palmitoyl transferase (CPT1). To elucidate this, we measured fatty acid utilization and oxidation in muscle after iv injection of leptin in vivo, by assessing the incorporation of [3H]-(R)-2-bromopalmitic acid and [14C]palmitic acid.[24] 2-(R)- bromopalmitic acid, as well as palmitic acid, is incorporated into cells, and converted to bromopalmitoyl-CoA, but it cannot be metabolized further. In contrast, palmitic acid is metabolized; it is partly accumulated into lipids and the rest is exported from cells through the process of oxidation. Thus, accumulation of 2-(R)-bromopalmitic acid and palmitic acid in tissues reflects the rate of fatty acid utilization and fatty acid incorporation into lipids, respectively. The difference between the accumulated amount of 2-(R)-bromopalmitic acid and palmitic acid indicates the rate of fatty acid oxidation. Intravenous leptin increased fatty acid oxidation in red skeletal muscles[24] as well as heart and BAT (unpublished data) at 6 h after the injection [Figures 1 and 4]. This effect was abolished by denervation of the sciatic, femoral, and obturator nerves, but not by denervation of the sciatic nerve alone.[24] It has been reported that leptin stimulates lipolysis in WAT.[44] Thus, leptin increases fatty acid oxidation in red muscle, coordinately enhancing lipolysis in WAT.

Recently, we and others revealed that leptin regulates food intake via changing hypothalamic AMPK activity.[45,46] In contrast to the effect on skeletal muscle, leptin inhibits AMPK in the ARC and PVN.[45,46] Constitutively active and dominant-negative AMPK are sufficient to change food intake, respectively. The decrease of AMPK activity in the hypothalamus is essential for the anorexic effect of leptin. Other anorexic factors, such as insulin and glucose, also suppress AMPK activity in the hypothalamus, whereas orexigenic hormone ghrelin activates the AMPK.[45,46] Although it is still unclear whether hypothalamic AMPK affects peripheral metabolism, it has been shown that direct modulation of fatty acid metabolism in the hypothalamus, which is a downstream of AMPK, regulates fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial function in muscle.[47]

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Leptin administration significantly improves impaired glucose metabolism in lipodystrophy and insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus. However, the mechanism still remains elusive. Our findings indicate that leptin stimulates muscle glucose uptake via the hypothalamic–sympathetic nervous system and β-adrenergic mechanism. Both VMN neurons and POMC neurons involve the leptin's action. Furthermore, leptin stimulates fatty acid oxidation in muscle via AMPK. The activation of muscle AMPK is mediated by two distinct mechanisms: one is a direct effect of leptin and another is mediated by the hypothalamic–sympathetic nervous system and a-adrenergic mechanism. Activation of AMPK by leptin phosphorylates and inhibits ACC, and results in potent stimulation of fatty acid oxidation in muscle. Although leptin likely has many functional roles in central and peripheral tissues, a physiologic role of leptin in muscle may play an important role in the regulation of glucose and fatty acid metabolism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Our work in this paper was partly supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (19390059, 21390067, to Y.M.), a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (17790634, 19790653 and 22790875, to T.S.; 23790282, to C.T.), and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (22126005, to Y.M.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan as well as by The Specific Research Fund of the National Institutes for Natural Sciences (to Y.M.).

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395:763–70. doi: 10.1038/27376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unger RH, Zhou Y-T, Orci L. Regulation of fatty acid homeostasis in cells: Novel role of leptin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2327–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimabukuro M, Koyama K, Chen G, Wang MY, Trieu F, Lee Y, et al. Direct antidiabetic effect of leptin through triglyceride depletion of tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4637–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimabukuro M, Zhou YT, Levi M, Unger RH. Fatty acid-induced beta cell apoptosis: A link between obesity and diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2498–502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimomura I, Hammer RE, Ikemoto S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Leptin reverses insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus in mice with congenital lipodystrophy. Nature. 1999;401:73–6. doi: 10.1038/43448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahn BB, Flier JS. Obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:473–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI10842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savage DB, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Disordered lipid metabolism and the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:507–20. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oral EA, Shima V, Ruiz E, Andewelt A, Premkumar A, Snell P, et al. Leptin-replacement therapy for lipodystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:570–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen KF, Oral EA, Dufour S, Befroy D, Ariyan C, Yu C, et al. Leptin reverses insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in patients with severe lipodystrophy. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1345–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI15001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moitra J, Mason MM, Olive M, Krylov D, Gavrilova O, Marcus-Samuels B, et al. Life without white fat: A transgenic mouse. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3168–81. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimomura I, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Ikemoto S, Bashmakov Y, Goldstein JL, et al. Insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus in transgenic mice expressing nuclear SREBP-1c in adipose tissue: Model for congenital generalized lipodystrophy. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3182–94. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chinookoswong N, Wang JL, Shi ZQ. Leptin restores euglycemia and normalizes glucose turnover in insulin-deficient diabetes in the rat. Diabetes. 1999;48:1487–92. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.7.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu X, Park B-H, Wang M-Y, Wang ZV, Roger H, Unger RH. Making insulin-deficient type 1 diabetic rodents thrive without insulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;95:2498–502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806993105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kojima S, Asakawa A, Amitani H, Sakoguchi T, Ueno N, Inui A, et al. Central leptin gene therapy, a substitute for insulin therapy to ameliorate hyperglycemia and hyperphagia, and promote survival in insulin-deficient diabetic mice. Peptides. 2009;30:962–6. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang M-Y, Chen L, Clark GO, Lee Y, Stevens RD, Ilkayeva OR, et al. Leptin therapy in insulin-deficient type I diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4813–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909422107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujikawa T, Chuang J-C, Sakata I, Ramadori G, Coppari R. Leptin therapy improves insulin-deficient type 1 diabetes by CNS-dependent mechanisms in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17391–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008025107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.German JP, Thaler JP, Wisse BE, Oh-IS, Sarruf DA, Matsen ME, et al. Leptin activates a novel CNS mechanism for insulin-independent normalization of severe diabetic hyperglycemia. Endocrinology. 2011;152:394–404. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denroche HC, Levi J, Wideman RD, Sequeira RM, Huynh FK, Covey SD, et al. Leptin therapy reverses hyperglycemia in mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes, independent of hepatic leptin signaling. Diabetes. 2011;60:1414–23. doi: 10.2337/db10-0958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ueno N, Inui A, Karla PS, Kalra SP. Leptin transgene expression in the hypothalamus enforces euglycemia in diabetic, insulin-deficient nonobese Akita mice and leptin-deficient obese ob/ob mice. Peptides. 2006;27:2332–42. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalra SP. Central leptin gene therapy ameliorates diabetes type 1 and 2 through two independent hypothalamic relays; a benefit beyond weight and appetite regulation. Peptides. 2009;30:1957–63. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minokoshi Y, Haque MS, Shimazu T. Microinjection of leptin into the ventromedial hypothalamus increases glucose uptake in peripheral tissues in rats. Diabetes. 1999;48:287–91. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haque MS, Minokoshi Y, Hamai M, Iwai M, Horiuchi M, Shimazu T. Role of the sympathetic nervous system and insulin in enhancing glucose uptake in peripheral tissues after intrahypothalamic injection of leptin in rats. Diabetes. 1999;48:1706–12. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.9.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toda C, Shiuchi T, Lee S, Yamato-Esaki M, Fujino Y, Suzuki A, et al. Distinct effects of leptin and a melanocortin receptor agonist injected into medial hypothalamic nuclei on glucose uptake in peripheral tissues. Diabetes. 2009;58:2757–65. doi: 10.2337/db09-0638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minokoshi Y, Kim YB, Peroni OD, Fryer LG, Müller C, Carling D, et al. Leptin stimulates fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nature. 2002;415:339–43. doi: 10.1038/415339a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamohara S, Burcelin R, Halaas JL, Friedman JM, Charron MJ. Acute stimulation of glucose metabolism in mice by leptin treatment. Nature. 1997;389:374–7. doi: 10.1038/38717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunbar JC, Hu Y, Lu H. Intracerebroventricular leptin increases lumbar and renal sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in normal rats. Diabetes. 1997;46:2040–3. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.12.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haynes WG, Morgan DA, Walsh SA, Mark AL, Sivitz WI. Receptor-mediated regional sympathetic nerve activation by leptin. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:270–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI119532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiuchi T, Haque MS, Okamoto S, Inoue T, Kageyama H, Lee S, et al. Hypothalamic orexin stimulates feeding-associated glucose utilization in skeletal muscle via sympathetic nervous system. Cell Metab. 2009;10:466–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nevzorova J, Evans BA, Bengtsson T, Summers RJ. Multiple signalling pathways involved in β2-adrenoceptor-mediated glucose uptake in rat skeletal muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:446–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huo L, Gamber K, Greeley S, Silva J, Huntoon N, Leng XH, et al. Leptin-dependent control of glucose balance and locomotor activity by POMC neurons. Cell Metab. 2009;9:537–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhillon H, Zigman JM, Ye C, Lee CE, McGovern RA, Tang V, et al. Leptin directly activates SF1 neurons in the VMH, and this action by leptin is required for normal body-weight homeostasis. Neuron. 2006;49:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bingham NC, Anderson KK, Reuter AL, Stallings NR, Parker KL. Selective loss of leptin receptors in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus results in increased adiposity and a metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2138–48. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu B, Goulding EH, Zang K, Cepoi D, Cone RD, Jones KR, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates energy balance downstream of melanocortin-4 receptor. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:736–42. doi: 10.1038/nn1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sternson SM, Shepherd GM, Friedman JM. Topographic mapping of VMH --> arcuate nucleus microcircuits and their reorganization by fasting. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1356–63. doi: 10.1038/nn1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song CK, Jackson RM, Harris RB, Richard D, Bartness TJ. Melanocortin-4 receptor mRNA is expressed in sympathetic nervous system outflow neurons to white adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1467–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00348.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song CK, Vaughan CH, Keen-Rhinehart E, Harris RB, Richard D, Bartness TJ. Melanocortin-4 receptor mRNA expressed in sympathetic outflow neurons to brown adipose tissue: Neuroanatomical and functional evidence. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R417–28. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00174.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Babic T, Purpera MN, Banfield BW, Berthoud HR, Morrison CD. Innervation of skeletal muscle by leptin receptor-containing neurons. Brain Res. 2010;1345:146–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hardie DG. AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinases: Conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:774–85. doi: 10.1038/nrm2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winder WW, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase, a metabolic master switch: Possible roles in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E1–10. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.1.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kishi K, Yuasa T, Minami A, Yamada M, Hagi A, Hayashi H, et al. AMP-Activated protein kinase is activated by the stimulations of G(q)-coupled receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:16–22. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iwabu M, Yamauchi T, Okada-Iwabu M, Sato K, Nakagawa T, Funata M, et al. Adiponectin and AdipoR1 regulate PGC-1α and mitochondria by Ca2+ and AMPK/SIRT1. Nature. 2010;464:1313–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka T, Masuzaki H, Yasue S, Ebihara K, Shiuchi T, Ishii T, et al. Central melanocortin signaling restores skeletal muscle AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell Metab. 2007;5:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abu-Elheiga L, Matzuk MM, Abo-Hashema KAH, Wakil SJ. Continuous fatty acid oxidation and reduced fat storage in mice lacking acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2. Science. 2001;291:2613–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1056843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tajima D, Masaki T, Hidaka S, Kakuma T, Sakata T, Yoshimatsu H. Acute central infusion of leptin modulates fatty acid mobilization by affecting lipolysis and mRNA expression for uncoupling proteins. Exp Biol Med. 2005;230:200–6. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minokoshi Y, Alquier T, Furukawa N, Kim YB, Lee A, Xue B, et al. AMP-kinase regulates food intake by responding to hormonal and nutrient signals in the hypothalamus. Nature. 2004;428:569–74. doi: 10.1038/nature02440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Minokoshi Y, Shiuchi T, Lee S, Suzuki A, Okamoto S. Role of hypothalamic AMP-kinase in food intake regulation. Nutrition. 2008;24:786–90. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cha SH, Rodgers JT, Puigserver P, Chohnan S, Lane MD. Hypothalamic malonyl-CoA triggers mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative gene expression in skeletal muscle: Role of PGC-1α. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15410–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607334103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]