Abstract

Background

Previous studies have suggested that n‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n‐3 PUFAs) have antiarrhythmic effects on atrial fibrillation (AF). We aimed to assess the effects of therapy with n‐3 PUFAs on the incidence of recurrent AF and on postoperative AF.

Methods and Results

Electronic searches were conducted in Web of Science, Medline, Biological Abstracts, Journal Citation Reports, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases. In addition, data from the recently completed FORωARD and OPERA trials were included. We included randomized controlled trials comparing treatment with n‐3 PUFAs versus control to (1) prevent recurrent AF in patients who underwent reversion of AF or (2) prevent incident postoperative AF after cardiac surgery. Of identified studies, 12.9% (16 of 124) were included, providing data on 4677 patients. Eight studies (1990 patients) evaluated n‐3 PUFA effects on AF recurrence among patients with reverted AF and 8 trials (2687 patients) on postoperative AF. Pooled risk ratios through random‐effects models showed no significant effects on AF recurrence (RR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.79 to 1.13; I2, 72%) or on postoperative AF (0.86; 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.04; I2, 53.1%). A funnel plot suggested publication bias among postoperative trials but not among persistent AF trials. Meta‐regression analysis did not find any relationship between doses and effects (P=0.887 and 0.833 for recurrent and postoperative AF, respectively).

Conclusions

Published clinical trials do not support n‐3 PUFAs as agents aimed at preventing either postoperative or recurrent AF.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO. Unique Identifier: CRD42012002199.

Keywords: arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, fatty acids, meta‐analysis, prevention

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in adults, and its incidence is increasing worldwide.1–2 Classic antiarrhythmic drugs used to preserve normal sinus rhythm in patients with previous AF have shown limited efficacy as well as frequent and serious harmful effects.3–5 For this reason, actively searching for antiarrhythmic agents without the common adverse events of classic antiarrhythmic drugs has become increasingly important.6–9 Although statins and angiotensin II receptor blockers may favorably affect the atrial remodeling associated with AF,6–8 the results of clinical trials have been neutral.9–11 In addition, new antiarrhythmic drugs proved to be neither more effective nor safer than classic therapies.12

N‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) from animal sources have shown antiarrhythmic properties on ventricular arrhythmia in patients with previous myocardial infarction,13–14 although recent findings failed to replicate these results.15–16 Encouraged by previous basic,17–18 epidemiological,19–20 and clinical data 13–14 on ventricular arrhythmias, a body of experimental data has suggested a potential role of these compounds in treating atrial arrhythmias.21–22 Clinical trials have focused their attention on 2 different populations: patients with persistent/paroxysmal AF for whom the principal objective is to preserve normal sinus rhythm after reversion and patients who have undergone cardiac surgery to prevent the onset of new AF. Overall, the results of clinical trials led to conflicting results. Previous systematic reviews failed to provide a definitive answer because the numbers of patients and events were relatively small,23–25 but since their publication, the number of patients available for assessment has more than doubled. Therefore, we have conducted a systematic review and meta‐analysis to evaluate the effects of n‐3 PUFAs on sinus rhythm maintenance after AF reversion and on AF incidence after cardiac surgery.

Methods

The protocol for our study is registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO). Registration number CRD42012002199 (available from http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42012002199). This systemic review is reported following recommendations of the PRISMA statement.26

Eligibility Criteria

To be included in the meta‐analysis, studies had to be randomized controlled trials evaluating any dose and formulation of n‐3 PUFAs, administered as pharmacological preparations and conducted in either of the following settings: sinus rhythm maintenance after spontaneous electrical or pharmacological cardioversion or AF prevention in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Studies could be double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, or unexposed controlled trials. In sinus rhythm maintenance trials, patients could be randomized with AF or in sinus rhythm (ie, before or after reversion).

In cardiac surgery trials, all patients had to be in sinus rhythm at randomization. No restriction criterion on type of surgery was adopted.

We excluded nonrandomized studies, those that did not reported data on atrial fibrillation occurrence during follow up, those with no follow‐up (ie, evaluating the electrophysiological effects of 1 or few doses of n‐3 PUFAs), and those that were reported in languages other than English.

Trials reported as proceeding abstracts were included if other inclusion criteria were met.

Search Strategy

We conducted an electronic search in the Web of Science database, simultaneously searching in the Web of Science database (from 1972 to November 6, 2012), Medline (from 1950 to November 6, 2012), Biological Abstracts (from 1995 to November 6, 2012) and Journal Citation Reports. We also electronically searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials database.

Search terms were “(n‐3 PUFA OR n 3 polyunsaturated OR fatty acids OR fish oil OR docosahexaenoic OR eicosapentaenoic OR polyunsaturated fatty acids) AND (atrial fibrillation OR atrial flutter) AND (random* OR randomised OR randomized),” searched in titles or as topics.

Additional searches included reference lists of relevant articles and reference lists of previous systematic reviews on this topic. Data from the recently released FORωARD (Fish Oil Research with ω‐3 for Atrial fibrillation Recurrence Delaying, Trial Registration Identifier: NCT00402363) trial were also included in the analyses.

Data Collection

Two investigators (J.M. and A.M.) independently collected information from studies retrieved by the initial search in an unblinded fashion. Titles and abstracts were scrutinized to check eligibility, and when inclusion and exclusion criteria were unclear, the full text report was evaluated.

Data abstracted from the included studies were authors, date of publication, design, comparator, dosage and formulation of n‐3 PUFA, loading dose, recurrent/incident AF definition, number of participants, patient characteristics, target population (ie, persistent AF or postoperative AF), type of surgery, and outcomes of interest. Abstracted data were collected in paper form and then entered in a database designed for the study. All discrepancies were solved by consensus with a third investigator (D.F.). No attempt was made to standardize definitions of end points. Quality of the studies was assessed using the score suggested by Jadad et al.27

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the occurrence of AF. For persistent AF studies, this was recurrent AF, and for postoperative studies, incident AF. Secondary outcomes were all‐cause mortality and length of ICU stay (only for postoperative studies).

Statistics

All analyses were conducted separately for trials of persistent AF and postoperative AF. For every study, we computed risk ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for outcomes in the n‐3 PUFA group compared with control/placebo group. Risk ratios from each individual trial were pooled using the random‐effects model approach as described by DerSimonian and Laird.28 For postoperative AF trials, we also computed mean length of ICU stay and pooled all means using weighted mean differences (also with a random‐effects model).

Heterogeneity was assessed through the Cochran Q test, with a P<0.1 indicating statistically significant heterogeneity. To further measure heterogeneity, inconsistency (ie, the I2 statistic) was computed, considering >50% as moderate inconsistency.29 Additional prespecified analyses to explore possible sources of heterogeneity between studies include a repeated pooled analysis excluding studies with less than the median quality score. Other sensitivity analyses by β‐blocker therapy, amiodarone therapy, age (≤ or >median), and sex were conducted. To further explore potential sources of heterogeneity in the estimated effect sizes between studies, we conducted meta‐regression analyses, in which the dependent variable (the [log] risk ratios) was weighted‐regressed against covariates at the study level (n‐3 PUFA dose, AF rate in the control group, quality score, mean age, proportion who were male, rate of β‐blocker and amiodarone use at baseline, left ventricular ejection fraction). Meta‐regression was conducted separately for recurrent AF studies and postoperative AF studies.30 Publication bias was evaluated using visual inspection of the funnel plot and Egger test, with P<0.1 indicating evidence of statistically significant asymmetry in the funnel plot.31

Results

Included Studies

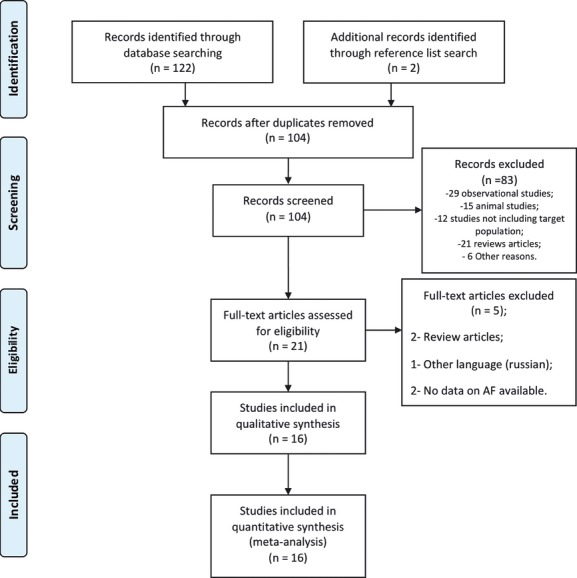

The electronic search identified 122 potentially eligible reports, of which 20 were eliminated as duplicates. After title and abstract assessment of the remaining 102 reports, 83 reports were excluded. Two additional studies were identified in the reference lists of relevant articles, yielding 21 reports that were retrieved for full‐text evaluation. Five additional studies were excluded, leaving 16 for our analysis32–47: 13 studies as journal articles and 3 as proceeding abstracts32–33 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Studies flow.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the studies. Overall, 4712 patients were included in the studies, but 35 patients were excluded from 2 trials,34–35 leaving 4677 patients for analyses. Eight studies (n=1990 patients) evaluated n‐3 PUFA effects on AF recurrence among patients with reverted persistent or paroxysmal AF.32–39 The other 8 trials (n=2687 patients) evaluated the effects on postoperative AF.40–47

Table 1.

Studies' Design and Quality Score

| Study | Year | Design | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Follow‐up | End‐Point Definition | N‐3 PUFA Dose | Ratio EPA/DHA | Assessment of Outcomes | Jadad's Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persistent or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation | ||||||||||

| Erdogan et al32 | 2007 | Triple blind | Persistent AF scheduled for external cardioversion | Cardiac or extracardiac abnormalities causing AF (mitral stenosis, hyperthyroidism) | 12 months | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | — |

| Margos et al33 | 2007 | Open label | Cardioverted persistent AF, euthyroid, and under anticoagulation | LVEF ≤40%, LA >55 mm or at least moderate valvular heart disease | 6 months | Persistent AF | N/A | N/A | 24‐hour Holter at 1 month and ECG at 1, 3, and 6 months | — |

| Kowey et al36 | 2010 | Double blind | Sinus rhythm and ≥1 suspected or documented episode of AF in the last 3 months and ≥1 documented episode of AF in the last 12 months. | Permanent AF, secondary AF, structural cardiac disease, use of antiarrhythmic drugs (class I or III, amiodarone in the last 6 months) | 6 months | Symptomatic recurrence of AF or flutter among paroxysmal AF patients. Symptomatic recurrence of AF or flutter among all patients was a secondary outcome. | 3.4 g/day | 1.24/1 | Transtelephonic monitoring and ECG | 5 |

| Bianconi et al35 | 2011 | Double‐blind | Persistent AF lasting more than 1 month and scheduled for electrical cardioversion | Use of n‐3 PUFA, MI in the last 3 months, uncompensated heart failure | 6 months | AF recurrence | 1.7 g/day | 1.2/1 | Transtelephonic monitoring and ECG | 5 |

| Özaydin et al37 | 2011 | Open‐label | Successful electrical cardioversion for persistent AF | Paroxysmal AF, left atrium >55 mm, moderate‐to‐severe heart valve disease, coronary artery disease, NYHA class III to IV heart failure | 12 months | AF >10 minutes | 0.6 g/d | 1.5/1 | ECG | 1 |

| Nodari et al34 | 2011 | Double blind | Persistent AF lasting ≥1 month, ≥1 relapse after successful previous cardioversion | Left atrium >60 mm, severe heart valve disease, myocardial infarction in previous 6 months | 12 months* | Sinus maintenance | 1.7 g/day | 1.2/1 | ECG and 24‐hour Holter monitoring at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months | 5 |

| Kumar et al38 | 2011 | Open label | Persistent AF, 18 to 85 years, scheduled for electrical cardioversion | Paroxysmal AF, left atrium >60 mm, severe heart valve disease, NYHA class IV heart failure. | 12 months | Persistent AF recurrence | 1.74 g/day | 1.4/1 | ECG | 2 |

| FORωARD39 | 2012 | Double blind | ≥2 Episodes of paroxysmal AF in the last 6 months (last episode within 3 months) or reverted persistent AF (within 3 to 28 days), and ≥65 years or moderate/high risk for stroke | Secondary AF, severe heart valve disease, NYHA classIV heart failure | 12 months | AF recurrence | 1 g/day | 1/1 | ECG | 5 |

| Postoperative atrial fibrillation | ||||||||||

| Calò et al40 | 2005 | Open label | Elective CABG | Valvular surgery, use of antiarrhythmic drugs (class I or III), history of supraventricular arrhythmias | In‐hospital | AF >5 minutes or requiring intervention | 1.7 g/day | 1:2 | Continuous rhythm monitoring for 2 to 5 days and ECG | 4 |

| Heidt et al41 | 2009 | Double blind | Elective CABG | Valvular surgery, use of antiarrhythmic drugs (class I or III), history of supraventricular arrhythmias | ICU stay | AF >15 minutes | 100 mg/kg per day IV | N/A | Continuous rhythm monitoring and ECG | 3 |

| Heidarsdottir et al42 | 2010 | Double blind | Elective or urgent cardiac surgery | <40 years, history of atrial arrhythmia, use of amiodarone or sotalol | In‐hospital (maximum 2 weeks) | AF >5 minutes | 2.2 g/day | 1.24/1 | Continuous rhythm monitoring | 3 |

| Saravanan et al43 | 2010 | Double blind | Elective isolated CABG on pump | History of atrial arrhythmias, use of antiarrhythmic drugs (class I or III) or n‐3 PUFA | In‐hospital | AF ≥30 seconds | 1.7 g/day | 1.2/2 | Continuous rhythm monitoring for 5 days, ECG thereafter | 4 |

| Sandesara et al44 | 2012 | Double blind | Elective CABG with or without valve surgery | Urgent or emergent surgery, chronic or persistent AF, use of antiarrhythmic drugs (class I or III) | 2 weeks | Documented AF (ECG or rhythm strip) requiring treatment | 1.7 g/day | 1.24/1 | Continuous rhythm monitoring during hospitalization, daily in‐hospital ECG and telephone interview | 4 |

| Sorice et al45 | 2011 | Open‐label | Elective CABG | History of AF, use of antiarrhythmic drugs (class I or III), valvular surgery | In‐hospital | AF >5 minutes | 1.7 g/day | 1.2/1 | Continuous rhythm monitoring for at least 4 days, daily ECG thereafter | 1 |

| Farquharson et al46 | 2011 | Double blind | Elective CABG and/or valve surgery | Previous AF or flutter, use of antiarrhythmic drugs (class I or III), NYHA class III to IV heart failure | In‐hospital (maximum 6 days) | AF or flutter ≥10 minutes or requiring intervention | 4.5 g/day | 1.42/1 | Continuous rhythm monitoring for 3 days, and daily ECG thereafter | 5 |

| OPERA47 | 2012 | Double blind | Cardiac surgery next day of randomization or later | Absence of sinus rhythm, existing or planned cardiac transplant, or use of left ventricular assist device | In‐hospital* | AF ≥30 seconds (ECG or rhythm strip) | 2 g/day | 1.24/1 | Continuous rhythm monitoring for ≥5 days, ECG thereafter | 5 |

PUFA indicates polyunsaturated fatty acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; AF, atrial fibrillation; N/A, not available; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LA, left atrial dimension; ECG, electrocardiogram; NYHA, New York Heart Association; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; ICU, intensive care unit.

Only patients with successful electrical cardioversion or spontaneous reversion entered in the follow‐up.

Follow‐up for mortality of 12 months.

Doses of n‐3 PUFA varied across studies from 0.6 to 4.5 g daily. All but 2 studies used an oral formulation (capsules): 1 study administered n‐3 PUFAs intravenously41 and the other46 as a liquid oil.

Among trials evaluating n‐3 PUFAs to prevent recurrence of AF after reversion, follow‐up ranged from 6 to 12 months. Assessment of outcomes included transtelephonic monitoring in 2 studies, 24‐hour Holter monitoring in 2 studies, and ECG in all studies that reported this information.

Studies evaluating n‐3 PUFAs to prevent AF after cardiac surgery had follow‐up limited to hospitalization: 1 study followed patients up to 14 days through telephone contact and the other up to 30 days.44,47 Methods to assess incident AF consisted of continuous monitoring for 2 to 5 days postsurgery and ECG thereafter in most studies, with only 1 study continuously monitoring patients for the complete hospital stay.42

Median sample size was 186 patients (189 among persistent AF studies and 181 among postoperative AF) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics

| Study | N | Age,* Mean | Male Sex, n (%) | Hypertension, n (%) | Previous MI, n (%) | Diabetes, n (%) | β‐Blockers, n (%) | Amiodarone, n (%) | LA mm*, Mean | LVEF,* % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persistent or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation | ||||||||||

| Erdogan et al32 | 108 | 65.0 | 78 (72.2) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Margos et al33 | 40 | 55.5 | 28 (70) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 23 (57.5) | 44.9 | 57.3 |

| Kowey et al36 | 663* | 60.5 | 373 (56) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 (0) | NA* | NA* |

| Bianconi et al35 | 214* | 69.2 | 129 (70) | 134 (71.7) | 18 (9.6) | 34 (18.2) | 84 (44.9) | 52 (27.8) | 44.9 | 57.7 |

| Özaydin et al37 | 47 | 61.5 | 20 (42.6) | 25 (53.2) | 0 (0) | 8 (17.0) | 12 (25.5) | 47 (100) | 44 | 60.5 |

| Nodari et al34 | 205* | 69.5 | 133 (66.8) | 87 (43.7) | 68 (34.2) | 69 (34.7) | 123 (61.8) | 199 (100) | 46 | 49.5 |

| Kumar et al38 | 182* | 62.0 | 138 (77.5) | 92 (51.7) | 31 (17.4) | 27 (15.2) | NA | 59 (33.2) | 45.8 | 58.4 |

| FORωARD39 | 586 | 66.1 | 321 (54.8) | 524 (91.4) | 67 (11.7) | 74 (12.9) | 353 (60.2) | 372 (63.5) | 29.1* | 60 |

| Postoperative atrial fibrillation | ||||||||||

| Calò et al40 | 160 | 65.6 | 136 (85) | 128 (80) | 84 (52.5) | 52 (32.5) | 92 (57.5) | 0 (0) | 39.7 | 55.8 |

| Heidt et al41 | 102 | 64.4 | 70 (68.6) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 (0) | 40.3 | 52.2 |

| Heidarsdottir et al42 | 168 | 67.0 | 133 (79.2) | 106 (63.1) | 26 (15.5) | 26 (15.5) | 126 (75) | 0 (0) | NA | 60 |

| Saravanan et al43 | 103 | 66.0 | 82 (79.6) | 33 (32) | 26 (25.2) | 15 (14.6) | 88 (85.4) | 0 (0) | NA* | NA* |

| Sandesara et al44 | 243 | 62.8 | 196 (80.7) | 215 (88.5) | 101 (41.6) | 88 (36.2) | 194 (80.0) | 0 (0) | 39.0 | 52.7 |

| Sorice et al45 | 201 | 63.2 | 164 (81.6) | 129 (64.2) | NA | 85 (42.3) | 121 (60.2) | 0 (0) | 40.6 | 52.5 |

| Farquharson et al46 | 194 | 64.0 | 142 (73.2) | 151 (77.8) | 68 (35) | 61 (31.4) | 80 (41.2) | 0 (0) | NA | 64.5 |

| OPERA47 | 1516 | 63.7 | 1094 (72.2) | 1135 (74.9) | 366 (24.1) | 393 (25.9) | 877 (57.9) | 58 (3.8) | 42.2 | 56.7 |

LA indicates left atrial dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Weighted means for medians across study level groups.

Six hundred forty‐five patients analyzed with available data in the modified intention‐to‐treat population.

LVEF <40% and LA >50 mm were exclusion criteria.

One hundred eighty‐seven patients in sinus rhythm included in the analyses of AF recurrence and 204 patients included in baseline descriptives, among 214 randomized in the trial.

One hundred ninety‐nine patients were analyzed among 205 originally randomized (6 patients refused cardioversion and were excluded from analyses).

Four patients had electrical cardioversion cancelled and were excluded from analyses.

Left atrial area.

LVEF ≤55% in 8.3% (n=9) of patients, LA ≥2.3 cm/m2 in 4.9% (n=5) of patients.

Median Jadad's score was 4 points, with 3 reports having <3 points.37–38,45 Studies evaluating n‐3 PUFAs to prevent recurrent AF had higher scores than postoperative studies (median, 5 versus 4 points, respectively).

Patients

Table 2 shows demographic, clinical, and echocardiographic characteristics of study participants. Most patients were male, and the mean age ranged between 55.5 and 69.5 years. There was high prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and previous myocardial infarction or coronary artery disease. Concomitant therapy with β‐blockers ranged from 25.5% to 84.5%. Use of amiodarone was an exclusion criterion in 8 studies and mandatory in 2 and varied from 3.8% to 63% in the remaining studies (1 study, reported as proceeding abstract, did not report this information). Mean left atrial dimension (or area) was mildly dilated in most studies, and mean left ventricular ejection fraction was in the normal range.

Outcomes

Maintenance of sinus rhythm after AF reversion studies

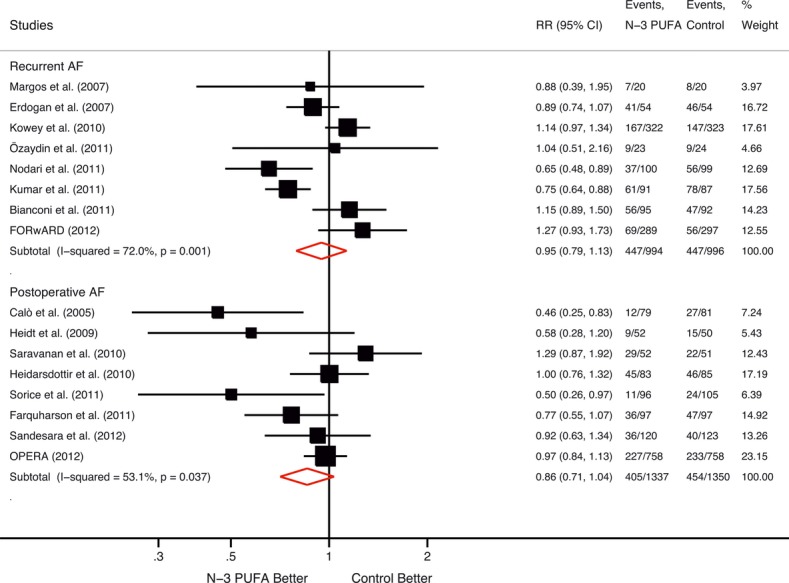

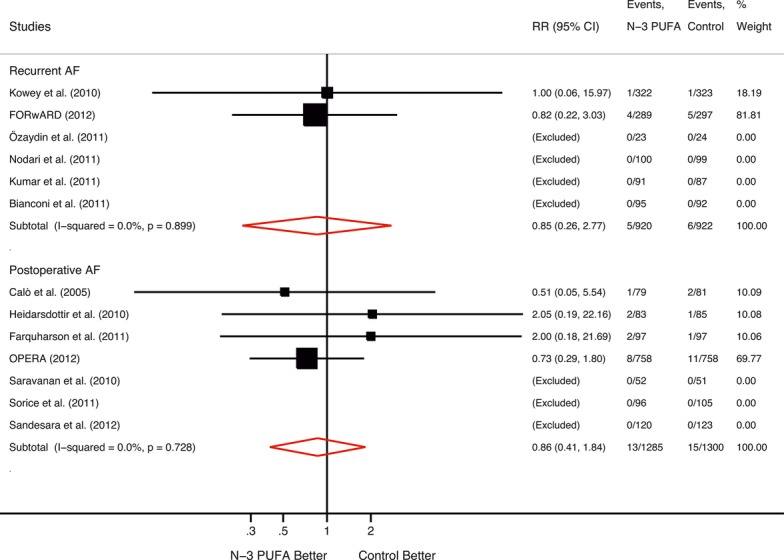

Figure 2 shows the cumulative results of n‐3 PUFAs on AF. Treatment had no effect on AF recurrence (RR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.79 to 1.13), with moderate inconsistency across trials (I2, 72.0%). Overall death rates were low among the 5 studies that reported this information, and there was no effect of n‐3 PUFAs on mortality (RR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.26 to 2.77; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Effects of n‐3 PUFA on AF. PUFA indicates polyunsaturated fatty acid; AF, atrial fibrillation; RR, relative risk.

Figure 3.

Effects of n‐3 PUFA on mortality. PUFA indicates polyunsaturated fatty acid; AF, atrial fibrillation; RR, relative risk.

Postoperative studies

Among studies evaluating the effects of n‐3 PUFAs to prevent postoperative AF, treatment resulted in nonsignificant reduction of AF during hospitalization (RR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.04), with moderate inconsistency (I2, 53.1%) (Figure 2). There were no effects on in‐hospital death across the 6 studies that reported this outcome (RR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.41 to 1.84; Figure 3).

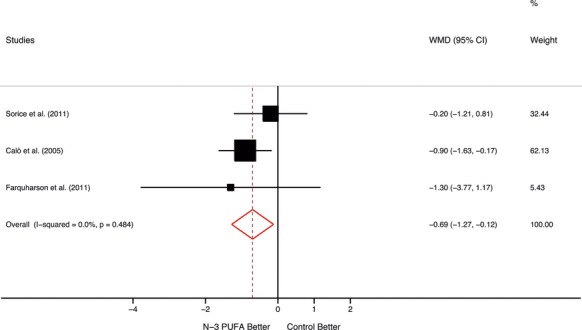

Three studies reported information on ICU length of stay. Treatment with n‐3 PUFAs resulted in significantly shorter stay compared with the control (weighted mean difference, −0.69; 95% CI, −1.27 to −0.12), with low inconsistency across trials (I2, 0.0%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of n‐3 PUFA on length of stay among postoperative AF trials. PUFA indicates polyunsaturated fatty acid; AF, atrial fibrillation; WMD, weighted mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

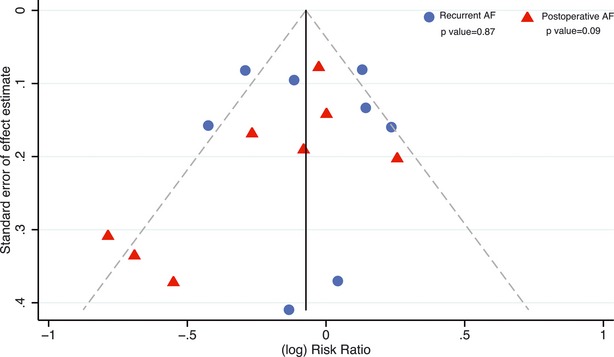

Publication Bias

Figure 5 shows a funnel plot. Formal testing of publication bias showed no evidence of bias among studies evaluating n‐3 PUFAs to prevent recurrent AF (P=0.87). Visual inspection of the funnel plot and formal testing of its asymmetry showed evidence of publication bias among studies assessing effects of n‐3 PUFAs to prevent postoperative AF (P=0.09).

Figure 5.

Publication bias assessment. AF indicates atrial fibrillation.

Sensitivity Analyses

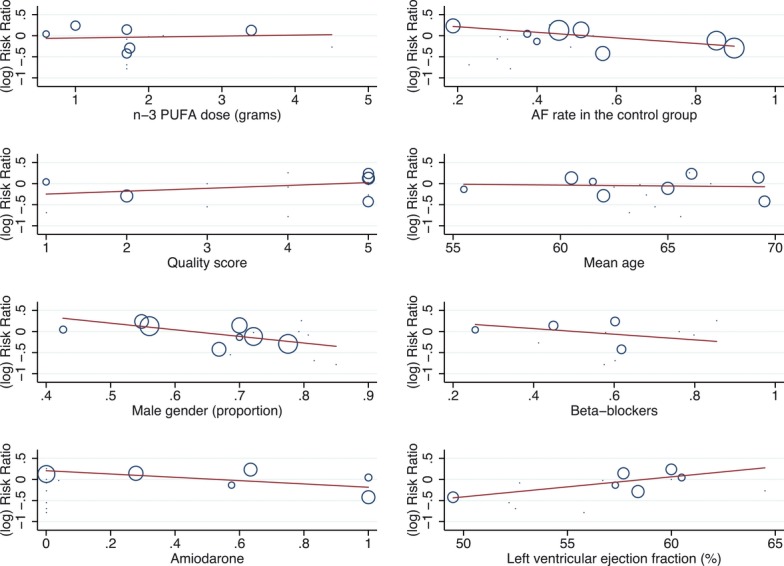

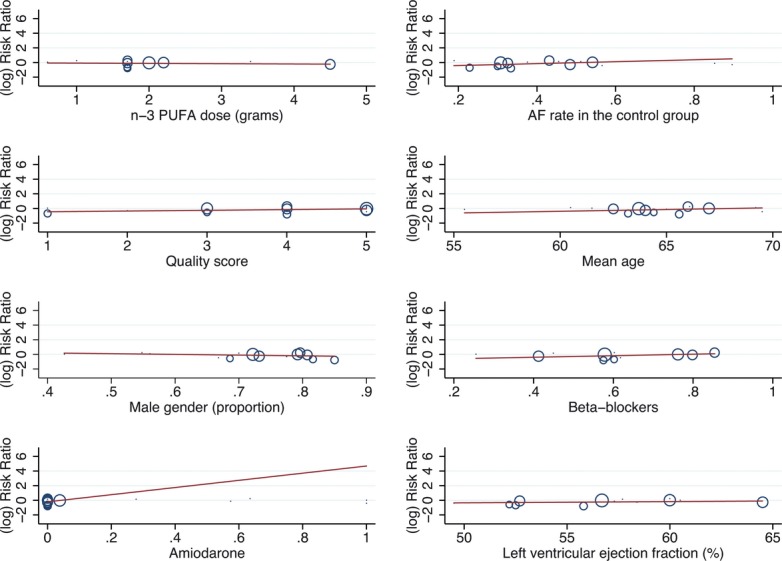

Repeated analyses excluding studies with a quality score lower than the median did not materially change the results. For AF recurrence studies, the risk ratio was 0.99 (95% CI, 0.83 to 1.20), and for postoperative AF, it was 0.89 (95% CI, 0.71 to 1.12). Other sensitivity analyses, including previous/concomitant use of β‐blockers, amiodarone, age, and sex did not provide different results (Table 3). Meta‐regression analyses suggested that the dose of n‐3 PUFAs did not influenced their effects (for recurrent AF, P=0.887; for postoperative AF, P=0.833). Additional meta‐regression analyses did not find associations between several study‐level covariates and the effect‐size estimates (Table 4 and Figures 6 and 7).

Table 3.

Sensitivity Analyses

| Characteristics | Recurrent AF | Postoperative AF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/Events | Pooled RR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | n/Events | Pooled RR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | |

| Quality score | ||||||

| <4 | 225/157 | 0.76 (0.65 to 0.89) | 0.0 | 471/150 | 0.72 (0.44 to 1.17) | 59.1 |

| ≥4 | 1765/743 | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.20) | 65.9 | 2206/709 | 0.89 (0.71 to 1.12) | 58.6 |

| Age, y | ||||||

| <64.2 | 910/486 | 0.93 (0.68 to 1.28) | 77.7 | 2154/654 | 0.86 (0.70 to 1.06) | 39.7 |

| ≥64.2 | 1080/408 | 0.96 (0.74 to 1.24) | 73.8 | 533/205 | 0.83 (0.54 to 1.26) | 69.7 |

| Male sex | ||||||

| <72% | 1704/668 | 1.03 (0.83 to 1.27) | 58.5 | 102/24 | 0.58 (0.28 to 1.20) | * |

| ≥72% | 286/226 | 0.81 (0.68 to 0.96) | 48.8 | 2585/835 | 0.88 (0.72 to 1.06) | 55.0 |

| β‐Blockers | ||||||

| <60% | 234/121 | 1.14 (0.89 to 1.46) | 0.0 | 1870/582 | 0.77 (0.54 to 1.09) | 70.6 |

| ≥60% | 1756/773 | 0.91 (0.74 to 1.12) | 77.4 | 817/277 | 0.90 (0.68 to 1.19) | 49.4 |

| Amiodarone | ||||||

| <58% | 872/432 | 1.13 (0.99 to 1.30) | 0.0 | 2687/859 | 0.86 (0.71 to 1.04) | 53.1 |

| ≥58% | 1117/462 | 0.86 (0.70 to 1.06) | 66.2 | — | — | — |

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

Only 1 study in the stratum.

Table 4.

Meta‐regression Analyses

| Covariates | Recurrent AF | Postoperative AF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI)* | P Value | Residual I2 (%) | Coefficient (95% CI)* | P Value | Residual I2 (%) | |

| n‐3 PUFA dose | 1.02 (0.67 to 1.57) | 0.891 | 80.7 | 0.96 (0.68 to 1.36) | 0.782 | 59.4 |

| AF rate in control group | 0.53 (0.31 to 1.04) | 0.070 | 40.2 | 3.73 (0.23 to 60.60) | 0.292 | 58.5 |

| Quality score | 1.07 (0.86 to 1.33) | 0.433 | 69.7 | 1.10 (0.85 to 1.43) | 0.385 | 56.4 |

| Mean age | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.06) | 0.877 | 75.8 | 1.05 (0.86 to 1.28) | 0.572 | 58.4 |

| Male sex* | 0.21 (0.04 to 1.25) | 0.075 | 44.6 | 0.38 (0.01 to 260.19) | 0.727 | 58.7 |

| β‐Blockers* | 0.51 (0.01 to 294.11) | 0.695 | 77.5 | 2.85 (0.44 to 18.50) | 0.209 | 51.4 |

| Amiodarone* | 0.68 (0.35 to 1.30) | 0.173 | 39.4 | 134.10 (0.01 to 510.10) | 0.566 | 56.4 |

| LVEF | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.15) | 0.222 | 68.0 | 1.02 (0.95 to 1.09) | 0.578 | 57.6 |

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Coefficients express the change in the (log) risk ratios for every increase in 1 unit in the value of the covariates.

Proportions in every study.

Figure 6.

Meta‐regression of recurrent AF studies. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid.

Figure 7.

Meta‐regression of postoperative AF studies. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid.

Discussion

The present systematic review was sufficiently powered (93% of power at the conventional type I error level of 0.05 to detect a 20% reduction in recurrent AF and 88% to detect a 15% reduction; these numbers for postoperative AF were 96% and 80%, to detect 20% and 15% reductions, respectively) to close the uncertainty that existed regarding potential effects of n‐3 PUFAs for the prevention of AF.

The data obtained with >4500 patients and 1753 events regarding the efficacy of n‐3 PUFAs in preventing recurrent AF showed that the effect of pharmacological supplementation with these compounds resulted in no benefit. That these results were obtained evaluating studies that included patients who were receiving amiodarone or β‐blockers and others that excluded these treatments and across a wide range of doses of n‐3 PUFA strengthen the main finding.

In the setting of secondary prevention of AF and beyond the heterogeneity observed in clinical trial designs, the number of patients and events collected in this meta‐analysis allows confidence in the main conclusion of neutral effects of n‐3 PUFAs for this clinical indication. Moreover—and for reasons that remain unclear—the 2 most recent trials conducted, which contributed a large number of patients and events,36,39 showed an excess accumulation of AF among patients randomized to n‐3 PUFAs compared with those assigned to placebo. When separately considering the results of individual clinical trials, it seemed appropriate to propose a large, “definitive” randomized trial, but this meta‐analysis would call for caution. The economic and logistic effort to conduct such a trial would be substantial, and the cumulative results seem to be confirmatory of no benefit.

Similarly, results obtained for the prevention of postoperative AF have also been disproved according to this analysis. The incorporation of a large and well‐conducted clinical trial47 provided strength to this systematic review, a characteristic that was not present in previous meta‐analyses.23–25

Other systematic reviews had appraised the evidence on the effects of n‐3 PUFAs to prevent AF23–25,48 with no definitive results, but our analysis, which more than doubled the number of patients and events, precludes any beneficial effects of n‐3 PUFAs for the prevention of secondary and postoperative AF.

Trials had different designs, and this resulted in an important degree of heterogeneity. Of note, the doses of n‐3 PUFAs varied nearly 10‐fold across studies. The present analysis also explored whether the effects of n‐3 PUFAs on AF prevention would vary with the dose used in different trials. The result of the meta‐regression does not support the hypothesis, as no relationship was observed between dose and effect. However, it also should be noted that the studies were too few to draw any definitive conclusion regarding the dose effect.

Besides AF prevention, cumulative results also failed to demonstrate any benefit of n‐3 PUFA supplementation on other relevant end points, including mortality, although all trials were underpowered to detect differences on this end point.

It is important to note that these trials were restricted to a particularly high‐risk population (ie, those under secondary prevention and those undergoing cardiovascular surgery), and these results should not be extrapolated to a potential beneficial effect of these compounds in the context of primary prevention of AF.

In addition, the trials had an inherent short duration. It could be the case that n‐3 PUFA supplementation would require a more prolonged duration of exposure to see a potential benefit.

In conclusion, the present meta‐analysis provides confident evidence of the lack of usefulness of oral supplementation of n‐3 PUFAs for the secondary prevention of AF and for the incidence of new AF in patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery.

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Magnani JW, Rienstra M, Lin H, Sinner MF, Lubitz SA, McManus DD, Dupuis J, Ellinor PT, Benjamin EJ. Atrial fibrillation: current knowledge and future directions in epidemiology and genomics. Circulation. 2011; 124:1982-1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heeringa J, van der Kuip DA, Hofman A, Kors JA, van Herpen G, Stricker BH, Stijnen T, Lip GY, Witteman JC. Prevalence, incidence and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27:949-953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lafuente‐Lafuente C, Mouly S, Longas‐Tejero MA, Bergmann JF. Antiarrhythmics for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD005049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connolly SJ, Camm AJ, Halperin JL, Joyner C, Alings M, Amerena J, Atar D, Avezum Á, Blomström P, Borggrefe M, Budaj A, Chen SA, Ching CK, Commerford P, Dans A, Davy JM, Delacrétaz E, Di Pasquale G, Diaz R, Dorian P, Flaker G, Golitsyn S, Gonzalez‐Hermosillo A, Granger CB, Heidbüchel H, Kautzner J, Kim JS, Lanas F, Lewis BS, Merino JL, Morillo C, Murin J, Narasimhan C, Paolasso E, Parkhomenko A, Peters NS, Sim KH, Stiles MK, Tanomsup S, Toivonen L, Tomcsányi J, Torp‐Pedersen C, Tse HF, Vardas P, Vinereanu D, Xavier D, Zhu J, Zhu JR, Baret‐Cormel L, Weinling E, Staiger C, Yusuf S, Chrolavicius S, Afzal R, Hohnloser SHPALLAS Investigators Dronedarone in high‐risk permanent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:2268-2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vassallo P, Trohman RG. Prescribing amiodarone: an evidence‐based review of clinical indications. JAMA. 2007; 298:1312-1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maggioni AP, Fabbri G, Lucci D, Marchioli R, Franzosi MG, Latini R, Nicolosi GL, Porcu M, Cosmi F, Stefanelli S, Tognoni G, Tavazzi LGISSI‐HF Investigators Effects of rosuvastatin on atrial fibrillation occurrence: ancillary results of the GISSI‐HF trial. Eur Heart J. 2009; 30:2327-2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pellegrini CN, Vittinghoff E, Lin F, Hulley SB, Marcus GM. Statin use is associated with lower risk of atrial fibrillation in women with coronary disease: the HERS trial. Heart. 2009; 95:704-708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maggioni AP, Latini R, Carson PE, Singh SN, Barlera S, Glazer R, Masson S, Cerè E, Tognoni G, Cohn JNVal‐HeFT Investigators Valsartan reduces the incidence of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure: results from the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val‐HeFT). Am Heart J. 2005; 149:548-557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GISSI‐AF Investigators Disertori M, Latini R, Barlera S, Franzosi MG, Staszewsky L, Maggioni AP, Lucci D, Di Pasquale G, Tognoni G. Valsartan for prevention of recurrent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:1606-1617N Engl J Med [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ACTIVE I Investigators Yusuf S, Healey JS, Pogue J, Chrolavicius S, Flather M, Hart RG, Hohnloser SH, Joyner CD, Pfeffer MA, Connolly SJ. Irbesartan in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:928-938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahimi K, Emberson J, McGale P, Majoni W, Merhi A, Asselbergs FW, Krane V, Macfarlane PWPROSPER Executive Effect of statins on atrial fibrillation: collaborative meta‐analysis of published and unpublished evidence from randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011; 342:d125010.1136/bmj.d1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobrev D, Nattel S. New antiarrhythmic drugs for treatment of atrial fibrillation. Lancet. 2010; 375:1212-1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dietary supplementation with n‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E after myocardial infarction: results of the GISSI‐Prevenzione trial. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell'Infarto miocardico. Lancet. 1999; 354:447-455LancetLancet [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchioli R, Barzi F, Bomba E, Chieffo C, Di Gregorio D, Di Mascio R, Franzosi MG, Geraci E, Levantesi G, Maggioni AP, Mantini L, Marfisi RM, Mastrogiuseppe G, Mininni N, Nicolosi GL, Santini M, Schweiger C, Tavazzi L, Tognoni G, Tucci C, Valagussa FGISSI‐Prevenzione Investigators Early protection against sudden death by n‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids after myocardial infarction: time‐course analysis of the results of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell'Infarto Miocardico (GISSI)‐Prevenzione. Circulation. 2002; 105:1897-1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yokoyama M, Origasa H, Matsuzaki M, Matsuzawa Y, Saito Y, Ishikawa Y, Oikawa S, Sasaki J, Hishida H, Itakura H, Kita T, Kitabatake A, Nakaya N, Sakata T, Shimada K, Shirato KJapan EPA Lipid Intervention Study (JELIS) Investigators Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomised open‐label, blinded endpoint analysis. Lancet. 2007; 369:1090-1098Lancet [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rauch B, Schiele R, Schneider S, Diller F, Victor N, Gohlke H, Gottwik M, Steinbeck G, Del Castillo U, Sack R, Worth H, Katus H, Spitzer W, Sabin G, Senges JOMEGA Study Group OMEGA, a randomized, placebo‐controlled trial to test the effect of highly purified omega‐3 fatty acids on top of modern guideline‐adjusted therapy after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2010; 122:2152-2159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao YF, Sigg DC, Leaf A. The antiarrhythmic effect of n‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: modulation of cardiac ion channels as a potential mechanism. J Membr Biol. 2005; 206:141-154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leaf A, Kang JX, Xiao YF, Billman GE. Clinical prevention of sudden cardiac death by n‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and mechanism of prevention of arrhythmias by n‐3 fish oils. Circulation. 2003; 107:2646-2652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kromhout D, Bosschieter EB, de Lezenne Coulander C. The inverse relation between fish consumption and 20‐year mortality from coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1985; 312:1205-1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He K, Song Y, Daviglus ML, Liu K, Van Horn L, Dyer AR, Greenland P. Accumulated evidence on fish consumption and coronary heart disease mortality: a meta‐analysis of cohort studies. Circulation. 2004; 109:2705-2711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jahangiri A, Leifert WR, Patten GS, McMurchie EJ. Termination of asynchronous contractile activity in rat atrial myocytes by n‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000; 206:33-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mozaffarian D, Psaty BM, Rimm EB, Lemaitre RN, Burke GL, Lyles MF, Lefkowitz D, Siscovick DS. Fish intake and risk of incident atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2004; 110:368-373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu T, Korantzopoulos P, Shehata M, Li G, Wang X, Kaul S. Prevention of atrial fibrillation with omega‐3 fatty acids: a meta‐analysis of randomised clinical trials. Heart. 2011; 97:1034-1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khawaja O, Gaziano JM, Djoussé L. A meta‐analysis of omega‐3 fatty acids and incidence of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Nutr. 2012; 31:4-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He Z, Yang L, Tian J, Yang K, Wu J, Yao Y. Efficacy and safety of omega‐3 fatty acids for the prevention of atrial fibrillation: a meta‐analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2013; 29:196-203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DGPRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009; 339:b253510.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996; 17:1-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986; 7:177-188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ. 2003; 327:557-560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson SG, Higgins JP. How should meta‐regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med. 2002; 21:1559-1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997; 315:629-634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erdogan A, Bayer M, Kollath D, Greiss H, Voss R, Neumann T, Franzen W, Most A, Mayer K, Tillmanns H. OMEGA AF Study: polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) for prevention of atrial fibrillation relapse after successful external cardioversion. Heart Rhythm. 2007; 4:S185-S186 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Margos P, Leftheriotis D, Katsouras G, Livanis EG, Kremastinos DT. Influence of n‐3 fatty acids intake on secondary prevention after cardioversion of persistent atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm. Europace. 2007; 9:iii51 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nodari S, Triggiani M, Campia U, Manerba A, Milesi G, Cesana BM, Gheorghiade M, Dei Cas L. n‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the prevention of atrial fibrillation recurrences after electrical cardioversion: a prospective, randomized study. Circulation. 2011; 124:1100-1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bianconi L, Calò L, Mennuni M, Santini L, Morosetti P, Azzolini P, Barbato G, Biscione F, Romano P, Santini M. n‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids for the prevention of arrhythmia recurrence after electrical cardioversion of chronic persistent atrial fibrillation: a randomized, double‐blind, multicentre study. Europace. 2011; 13:174-181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kowey PR, Reiffel JA, Ellenbogen KA, Naccarelli GV, Pratt CM. Efficacy and safety of prescription omega‐3 fatty acids for the prevention of recurrent symptomatic atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010; 304:2363-2372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozaydın M, Erdoğan D, Tayyar S, Uysal BA, Doğan A, Içli A, Ozkan E, Varol E, Türker Y, Arslan A. N‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids administration does not reduce the recurrence rates of atrial fibrillation and inflammation after electrical cardioversion: a prospective randomized study. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2011; 11:305-30910.5152/akd.2011.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar S, Sutherland F, Morton JB, Lee G, Morgan J, Wong J, Eccleston DE, Voukelatos J, Garg ML, Sparks PB. Long‐term omega‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation reduces the recurrence of persistent atrial fibrillation after electrical cardioversion. Heart Rhythm. 2012; 9:483-491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macchia A, Grancelli H, Varini S, Nul D, Laffaye N, Mariani J, Ferrante D, Badra R, Figal J, Ramos S, Tognoni G, Doval HC. GESICA Investigators. Omega‐3 Fatty Acids for the Prevention of Recurrent Symptomatic Atrial Fibrillation: Results of the FORWARD (Randomized Trial to Assess Efficacy of PUFA for the Maintenance of Sinus Rhythm in Persistent Atrial Fibrillation) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61:463-468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calò L, Bianconi L, Colivicchi F, Lamberti F, Loricchio ML, de Ruvo E, Meo A, Pandozi C, Staibano M, Santini M. N‐3 Fatty acids for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 45:1723-1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heidt MC, Vician M, Stracke SK, Stadlbauer T, Grebe MT, Boening A, Vogt PR, Erdogan A. Beneficial effects of intravenously administered N‐3 fatty acids for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery: a prospective randomized study. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009; 57:276-280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heidarsdottir R, Arnar DO, Skuladottir GV, Torfason B, Edvardsson V, Gottskalksson G, Palsson R, Indridason OS. Does treatment with n‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids prevent atrial fibrillation after open heart surgery? Europace. 2010; 12:356-363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saravanan P, Bridgewater B, West AL, O'Neill SC, Calder PC, Davidson NC. Omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation does not reduce risk of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010; 3:46-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sandesara CM, Chung M, Van Wagoner D, Barringer T, Allen K, Ismail H, Zimmerman B, Olshansky BFISH Trial Investigators A Randomized, Placebo‐Controlled Trial of Omega‐3 Fatty Acids for Inhibition of Supraventricular Arrhythmias After Cardiac Surgery: The FISH Trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012; 1:e00054710.1161/JAHA.111.000547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sorice M, Tritto FP, Sordelli C, Gregorio R, Piazza L. N‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids reduces post‐operative atrial fibrillation incidence in patients undergoing “on‐pump” coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2011; 76:93-98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farquharson AL, Metcalf RG, Sanders P, Stuklis R, Edwards JR, Gibson RA, Cleland LG, Sullivan TR, James MJ, Young GD. Effect of dietary fish oil on atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2011; 108:851-856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mozaffarian D, Marchioli R, Macchia A, Silletta MG, Ferrazzi P, Gardner TJ, Latini R, Libby P, Lombardi F, O'Gara PT, Page RL, Tavazzi L, Tognoni GOPERA Investigators Fish oil and postoperative atrial fibrillation: the omega‐3 fatty acids for prevention of post‐operative atrial fibrillation (OPERA) RANDOMIZED Trial. JAMA. 2012; 308:2001-201110.1001/jama.2012.28733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cao H, Wang X, Huang H, Ying SZ, Gu YW, Wang T, Huang CX. Omega‐3 fatty acids in the prevention of atrial fibrillation recurrences after cardioversion: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Intern Med. 2012; 51:2503-2508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]