Abstract

Objective

Innate immunity drives numerous cardiovascular pathologies. Vein bypass grafting procedures are frequently accompanied by low-grade wound contamination. We hypothesized that a peri-graft innate immune challenge, via an outside-in route, augments inflammatory responses, which subsequently drive a component of negative vein graft wall adaptations; moreover, adipose tissue mediates this immune response.

Methods

The inferior vena cava from a donor mouse was implanted into the common carotid artery of a recipient mouse utilizing a validated cuff technique (9-week-old male C57BL/6J mice). Slow-release low-dose (5 μg) lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (n = 9) or vehicle (n = 9) was applied peri-graft; morphologic analysis was completed (day 28). In parallel, vein-grafted mice received peri-graft LPS (n = 12), distant subcutaneous LPS (n = 6), or vehicle (n = 12), then day-1 and -3 harvest of grafts and adipose tissue for cytokines and toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling mRNA expression (qRT-PCR).

Results

All recipient mice survived, and all vein grafts were patent. Acute low-dose local LPS challenge enhanced vein graft lumen loss (P = .04) and tended to augment intimal hyperplasia (P = .06). The surgical trauma of vein grafting universally upregulated key pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators within the day-1 graft wall, but varied on TLR signaling gene expression. Local and distant LPS accentuated these patterns until at least postoperative day 3. LPS challenge enhanced the inflammatory response in adipose tissue (locally > distantly); local LPS upregulated adipose TLR-4 dramatically.

Conclusions

Perivascular and distant inflammatory challenges potentiate the magnitude and duration of inflammatory responses in the early vein graft wall, negatively modulating wall adaptations, and thus, potentially contribute to vein graft failure. Furthermore, surgery activates innate immunity in adipose tissue, which is augmented (regionally > systemically) by LPS. Modulation of these local and distant inflammatory signaling networks stands as a potential strategy to enhance the durability of vascular interventions such as vein grafts. (J Vasc Surg 2013;57:486-92.)

Clinical Relevance

Vein graft failure is traditionally considered as a process driven by luminal hemodynamic forces and endothelial injury. We report that the “outside-in” mechanism of local perivascular and distant inflammatory challenges potentiate the magnitude and duration of inflammatory responses in the early vein graft wall, negatively modulating wall adaptations, and thus potentially contribute to vein graft failure. Modulation of these inflammatory signaling networks (eg, extension of antibiotic administration beyond standard wound prophylaxis regimens) stands as a potential strategy to enhance the durability of vascular interventions such as vein grafts.

Clinical vein graft durability remains limited, and failure mechanisms have historically been attributed to factors such as hemodynamic forces and inflammation acting largely via the luminal surface. The innate immune system evolved to protect the host from invading pathogens, and it participates in the tissue response to injury.1 Its activation in the context of vascular injury has been increasingly associated with cardiovascular pathologies.2 For instance, inflammatory biomarkers of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and serum amyloid A are correlated with the severity of peripheral arterial diseases, and elevated C-reactive protein is associated with increased risk for postoperative vascular events.3 Innate inflammation has been also linked to the pathogenesis and progression of atherosclerosis and thrombosis.4 Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play key roles in innate mediated events, and are associated with intimal hyperplasia in the setting of arterial injury5 and metabolic disorders such as obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus.6-8 Recent evidence specifically suggests that TLR-4 also regulates the adaptive response of vein grafts to arterialization.9

Various host contexts activate innate immunity. Infection, whether chronically in the form of periodontal disease or acutely in the setting of surgical site infection, can prime the host immune response.10 A vein bypass grafting procedure usually takes many hour to perform, and low-grade bacterial contamination likely occurs (as high as 79%11) in most cases. Wound complications/infections have been identified as independent predictors of accelerated vein graft failure.12 Furthermore, vein conduits often lie adjacent to soft tissues such as adipose tissue, which is capable of orchestrating local inflammatory responses.13-16 These example host settings may upregulate vascular inflammation, but direct evidence linking a hyperactive immune response (originating from a perivascular stimulus such as local wound contamination) to vein graft failure remains sparse.

We, thus, hypothesized that a local immune challenge initiated in the perivascular space can lead to an exaggerated inflammatory response that elicits vein graft wall events via an “outside-in” paradigm to drive subsequent negative adaptations. In addition, adipose tissue, being an anatomically dominant component of the peri-graft space, can potentially function as a mediator of this host innate immune response.

METHODS

The mouse vein graft model

Nine-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Me). Animals were maintained on a 12-hour light-dark cycle, and received water and standard chow ad libitum. All animal experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health Publication No. 85-23, Revised 1996).

Operative procedures were performed aseptically, with general continuous inhalant anesthesia (1%-2% isoflurane mixed with 1 L/min oxygen), using a Zeiss binocular OPMI-MD Surgical Microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc, Oberkochen, Germany).

A mouse vein bypass isograft model was created via interposition of a supradiaphragmatic inferior vena cava (IVC) from a donor mouse into the common carotid artery of a recipient mouse as previously reported.17,18 Briefly, the mouse right common carotid artery was dissected and ligated with 9-0 nylon sutures at the midpoint and divided. After clamping, the ligatures were removed and the proximal and distal artery ends were everted over premade polyetheretherketone cuffs (Zeus Inc, Orangeburg, SC). The IVC was then sleeved over the cuffed arterial ends and secured into position with 9-0 sutures.

Morphologic impact of low-dose perivascular lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge on mouse vein grafts

Experimental groups are shown in Table I. Biologically inert pluronic F-127 gel (# P2443; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo) served as a sustained release vehicle19,20 to deliver LPS (lipopolysaccharide suspended in pluronic F-127 gel [gLPS]; from E coli; # L4391; Sigma Aldrich; n = 9) or control normal saline (gNS; n = 9) on mouse vein grafts. Briefly, pluronic gel powder was sterilized via autoclave, then reconstituted (40% w/v) in filtered 0.9% saline. Low-dose LPS was then combined with the gel to create a suspension that was placed via syringe (5 μg LPS/40 μL, per application) topically on the mid- and distal-graft immediately after vein bypass construction. The proximal vein graft is obscured by the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Table I.

Experimental groups and numbers of (recipient) mice

| Groups | Day 0 | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) gLPS VG | 9 | |||

| (2) gNS VG | 9 | |||

| (3) Normal mice for harvesting IVC and flank SC adipose |

6 | |||

| (4) gNS VG + gNS flank SC adipose |

6 | 6 | ||

| (5) gNS VG + gLPS flank SC adipose |

6 | |||

| (6) gLPS VG + gNS flank SC adipose |

6 | 6 |

LPS, Lipopolysaccharide suspended in pluronic F-127 gel; NS, normal saline suspended in pluronic F-127 gel; IVC, inferior vena cava; SC, subcutaneous; VG, vein graft.

Blood was collected via the retro-orbital technique at days 1 and 7 postoperatively, and plasma was used for systemic cytokine analysis (including tumor necrosis factor-alpha [TNF-α], interleukin [IL]-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-12 p40 and p70, IL-13, and IL-17) by custom-made Luminex multiplex cytokine-detection bead assay platform using a Luminex 200 instrument (Luminex Corp, Austin, Tex).

At postoperative day 28, vein grafts were harvested via whole-body perfusion fixation (10% formalin) under physiological mean arterial pressure (100 mm Hg). After standard tissue processing, paraffin embedding, and sectioning (6 μm), cross-sections for Masson’s trichrome staining were obtained 600 μm and 800 μm (one from each location) from the landmark (distal cuff edge) to avoid artifact from the anastomotic cuffs and to assay the area exposed to the gel.

Digital microscopic images were captured using an Axio A1 microscope (Carl Zeiss). Lumen boundary, internal elastic lamina, and outside boundary of the Masson’s stained vein graft cross sections were determined as described before17,18 (Fig 1, A and B), and planimetry was completed by a blinded researcher using AxioVision Rel 4.7 software (Carl Zeiss). The morphologic calculation methods were previously described.18

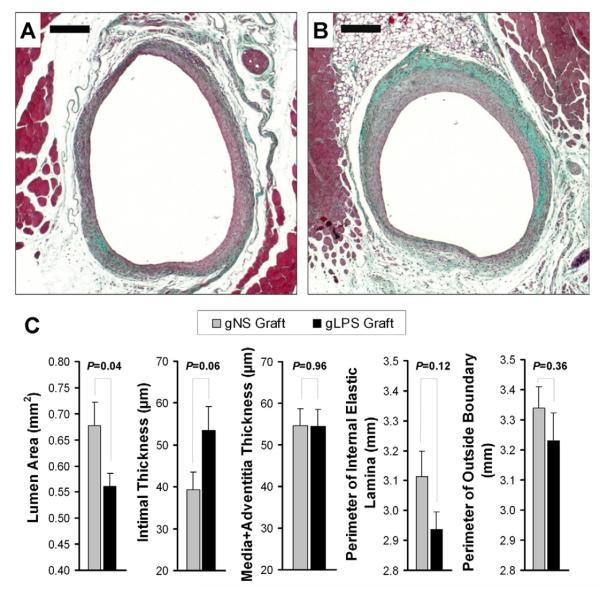

Fig 1.

Morphologic analysis of day 28 mouse vein grafts. A-B, Representative Masson’s trichrome stained images. A, Normal saline suspended in pluronic F-127 gel (NS) vein graft. B, Lipopolysaccharide suspended in pluronic F-127 gel (LPS) vein graft. Scale bar = 200 μm. C, The comparison of vein graft lumen area, intimal thickness, media + adventitia thickness, the perimeter of internal elastic lamina, and the perimeter of outside boundary, based on Masson’s stained images. Values are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean.

Leukocyte immunohistochemical staining was completed using rat anti-mouse CD45 (1:50; # 550539; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif) as the primary antibody, biotin conjugated anti-rat IgG2b (1:100; # 550327; BD Pharmingen) as the secondary antibody, and with antigen retrieval technique (citrate buffer, pH = 6.0). Positive cells were counted per defined area of the vein graft wall.

Early vein graft inflammation/adipose signaling events

Separate experiments were performed to investigate early vein graft wall inflammatory changes, as well as to determine the impact of local vs distant innate immune challenges with LPS. Carotid interposition isografts were performed in C57BL/6J mice as described above. gLPS was applied at peri-graft space or injected into distant (flank) subcutaneous adipose tissue with the same dose as stated above; control animals received gNS vehicle. Vein grafts and adipose tissue at the distant injection site were harvested at days 1 and 3 postoperatively and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. IVC and flank subcutaneous adipose tissue from normal mice were also collected as baseline samples (Table I).

Total RNA was isolated from vein grafts and adipose tissue using RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN Inc, Valencia, Calif) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Temporal expression patterns of key pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators (CCL2, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and TNFAIP3) as well as components of the TLR pathway (TLR-4, TLR-2, CD14, Myd88, IKBKB, and MAP3K1) were determined by qRT-PCR using Mouse Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathway PCR Array (# PAMM-018; SABiosciences, QIAGEN Inc) per manufacturer’s instructions (interrogated genes shown in Table II). Relative mRNA expression levels were indexed using Hprt1 (Hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase) and Hsp90ab1 (Heat shock protein 90 alpha cytosolic class B) as housekeeping genes and the 2[−ΔΔC(T)] method.

Table II.

Interrogated mediators

| CCL2 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (MCP-1) |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| TNFAIP3 | Tumor necrosis factor, alpha-induced protein 3 |

| TLR-4 | Toll-like receptor-4 |

| TLR-2 | Toll-like receptor-2 |

| CD14 | CD14 molecule |

| Myd88 | Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 |

| IKBKB | Inhibitor of kappa B kinase beta |

| MAP3K1 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1 |

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean. Comparison of more than two groups was performed via one-way analysis of variance; comparison of two groups was performed via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. Statistical tests were completed with SigmaPlot v 11.0 (SYSTAT Software Inc, San Jose, Calif) or Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Wash). A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

All recipient mice survived until harvest, and all vein grafts were patent. One gNS vein graft specimen was microscopically uninterpretable and excluded from subsequent analysis.

Acute local LPS challenge enhances negative wall remodeling and intimal hyperplasia in day-28 vein grafts

Acute local innate immune challenge during the early stages of vein grafting led to significant vein graft lumen area loss (0.56 ± 0.03 mm2 gLPS vs 0.68 ± 0.04 mm2 gNS; P = .04), with trends toward exaggeration of intimal thickness (53.5 ± 5.6 μm gLPS vs 39.2 ± 4.4 μm gNS; P = .06) and inward remodeling (internal elastic lamina length) (2.94 ± 0.06 mm gLPS vs 3.11 ± 0.09 mm gNS; P = .12) in peri-graft-gLPS mice (Fig 1). No significant difference between two groups in leukocyte localization was observed on CD45 stained cross sections (Supplementary Fig, online only). Systemic plasma levels of inflammatory mediators demonstrated no significant difference between LPS and saline treatment at postoperative days 1 and 7 (Supplementary Table, online only), suggesting largely paracrine instead of endocrine effects.

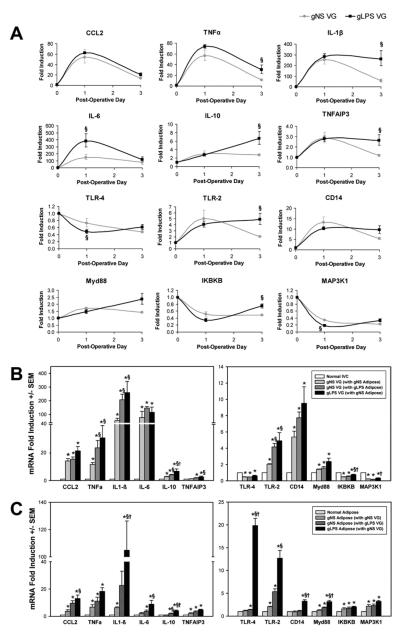

Local and distant LPS challenges induce an exaggerated inflammation response of early vein graft wall

Surgical trauma of vein bypass grafting universally upregulated key pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators (CCL2, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and TNFAIP3) within the vein graft wall at the immediate postoperative time (day 1). However, there were subtle differences in the magnitude of the inflammatory response between the treatment groups: IL-6 cytokine expression appeared significantly higher in gLPS-graft animals (2.6-fold higher increase relative to elevated response seen in gNS vein grafts) (Fig 2, A). At 3 days, inflammation within the vein graft wall began to subside as inflammatory mediator gene expression was dampened. gLPS-graft mice, however, exhibited sustained up-regulation of IL-1β, IL-10, and TNFAIP3, as well as higher levels of TNF-α (Fig 2, A and B).

Fig 2.

mRNA expression of inflammatory mediators. Data are shown as fold induction ± standard error of the mean. A, Vein graft (VG) wall at baseline day 0, and postoperative days 1 and 3. §Relative to normal saline suspended in pluronic F-127 gel (gNS) VG at the same time point, P < .05. B, VG wall at postoperative day 3. *Relative to normal inferior vena cava (IVC), P <.05; §Relative to gNS VG (with gNS adipose), P < .05; †Relative to gNS VG (with lipopolysaccharide suspended in pluronic F-127 gel [LPS] adipose), P < .05. C, Distant (flank) adipose tissue at postoperative day 3. *Relative to normal adipose, P < .05; §Relative to gNS adipose (with gNS VG), P < .05; †Relative to gNS adipose (with gLPS VG), P < .05. IL, Interleukin; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

Concurrent with the rise in pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine expression within the vein graft wall in this early time frame is an upregulation of TLR-2, CD14, and Myd88. TLR-4 and key upstream inflammatory mediators IKBKB and MAP3K1 were downregulated at both days 1 and 3 (Fig 2, A and B).

Distant subcutaneous LPS challenge (essentially mimicking a remote bacterial contamination/infection) also contributed to the inflammatory changes within the vein graft wall in a similar pattern. The overall magnitude is albeit less than local LPS challenge (Fig 2, B).

Adipose tissue contribution to inflammation

Inflammatory changes also occurred in distant subcutaneous adipose tissue of animals undergoing surgical trauma of vein grafting. There were significant increases in CCL2, TNF-α, IL-1β, and TNFAIP3 expression in the early postoperative period from baseline. LPS challenge enhanced this inflammatory response in adipose tissue (locally > distantly); there were sustained upregulation of CCL2, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and TNFAIP3 at day 3 postoperatively. Distinctive from the inflammatory response seen within the vein graft wall, LPS-challenged adipose tissue also exhibited increased TLR-4, IKBKB, and MAP3K1 expression in addition to upregulation of TLR-2, CD14, and Myd88 (Fig 2, C).

DISCUSSION

Vein grafts morphologically adapt to their new arterialized environment through myofibroblast proliferation and wall thickening, and innate immunity has been implicated as playing a role in this early adaptive response via endogenous signals.9 Ongoing vascular inflammation initiated via tissue traumatic injury from vein grafting and exacerbated by host biological and hemodynamic factors can theoretically accelerate intimal hyperplasia, progressive lumen loss and graft failure.21-27 The current study provides direct evidence that exacerbation of abluminal host immunity can enhance inflammation and vein graft lumen loss. While efforts are made to avoid operation in clinically infected patients, the data point out that low-grade wound contamination can drive nonvascular wall inflammation that can drive revascularization failure. One can speculate that antibiotics beyond those utilized for surgical wound prophylaxis, or anti-inflammatory strategies directed at tissues beyond the vein graft wall (eg, adipose) around the time of operation might enhance revascularization durability.

We selected LPS as a strategic research tool to prime the host innate immune system and exaggerate the inflammatory response associated with surgical trauma in the early stages of vein graft adaptation. This traditional immune challenge enhanced lumen loss and neointimal proliferation, as seen on the morphologic analyses of the vein graft walls after 28 days. The lack of difference in CD45 staining within the day-28 vein graft wall of two groups suggests that the diverse events elicited may occur at an early time points.

Supporting prior reports,23,24,28 longitudinal investigation of this early window of vein graft inflammatory dynamics revealed an elevation of proinflammatory cytokines in the immediate postoperative period, followed by resolution of inflammation over time as anti-inflammatory mechanisms are activated. In local gLPS challenged mice, there was a higher initial surge in IL-6 expression, followed by more sustained up-regulation of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, and TNFAIP3, suggesting ongoing inflammation within the vein graft wall. These downstream changes were associated with TLR-2 and Myd88 stimulation, and concurrent increase in CD14 marker suggesting macrophage participation. However, TLR-4 was downregulated, along with key upstream mediators IKBKB and MAP3K1. While TLR-4 is often classically associated with LPS challenge, preferential stimulation of TLR-2 over TLR-4 may be related to the tissue specific response of vein grafts, as well as the particular variant of LPS used.10,29-33 Downregulation of upstream mediators IKBKB and MAP3K1 kinase in spite of persistent inflammatory cytokine expression may be related to suppression from negative feedback mechanisms at the particular time points sampled. Persistent inflammatory cytokine expression may also be elicited by alternative inflammatory pathways, or may reflect a complex network of cellular interactions and contributions from perivascular environment.

Indeed, the inflammatory dynamics from subcutaneous adipose tissue in response to LPS challenge is distinct from that seen in vein graft. LPS induced pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine expression is directly related to upregulation of TLR-4, TLR-2, CD14, and Myd88, even at 3 days postoperatively. In addition, simple stress from surgical trauma elicited adipose tissue inflammation that may contribute via paracrine and endocrine fashion to the overall vascular inflammatory response.

While no significant difference in plasma cytokine levels between gLPS-graft and saline-graft animals existed during this early time frame, distant LPS challenge does contribute to the overall inflammatory response seen in vein graft as well as adipose tissue. These changes may be related to a primed systemic cellular response that can intravascularly home to sites of active injury. The effect from local LPS induced immunity remains more pronounced than distant systemic contributions, and this highlights the important contribution of outside-in mechanisms of vascular inflammation to vein graft failure.

The current study is limited to the use of a known potent innate immune activator (LPS) to elicit the host innate immune response. The single, relatively low dose (5 μg) of LPS was selected based upon the literature and preliminary studies indicating that it elicited inflammation without causing overt local wound complications or acute illness in the animals. Immune challenge with live microbial organisms would potentially lead to lack of experimental reproducibility due to inoculum success variation. Furthermore, the impact of gram-positive bacterial components such as lipoteichoic acid has not been explored, although they have been shown to mechanistically activate similar TLR pathways to initiate inflammation. We built the experiments on short-term RNA dynamics at a time point when the biological response to vein grafting tends to be high.23,24 Confirmatory protein quantifications and information on the cellular mediators are not offered, and this is limited by the tissue amounts available in these small vein graft samples in the early postoperative period. Finally, it is certainly acknowledged that perivascular immune events are just one of a host of factors (luminally mediated, hemodynamic, etc) that drive negative vein graft wall remodeling and intimal hyperplasia. However, these experiments directly bring to light this previously underappreciated but clinically relevant factor in this complex orchestra of events.

In conclusion, we found that a single early perivascular inflammatory challenge negatively modulates subsequent vein graft adaptations. Furthermore, surgery also activates innate immune pathways in the vein graft wall and adipose tissue that are augmented (regionally > systemically) by LPS. Thus, mechanistic studies into vascular adaptations to acute physical interventions should look beyond the vascular wall into the surrounding local tissues such as adipose tissue since they can contribute to the overall vascular adaptation. Recognizing the settings of activated host immunity and mitigating overexpression especially in the critical early phases of vein graft adaptation may lead to viable therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig (online only). CD45 immunohistochemical analysis of day 28 mouse vein grafts. A, Representative image of normal saline suspended in pluronic F-127 gel (NS)-treated vein graft. B, Representative image of lipopolysaccharide suspended in pluronic F-127 gel (LPS)-treated vein graft. The hand-digitally drawn yellow lines delineate the internal elastic laminas of vein graft walls. Red arrows show the representative positive cells. Scale bar = 50 μm. C, Quantitative analysis based on CD45 immunohistochemical images. Values are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean. There is no statistical difference between two groups for the various vascular wall layers.

Supplementary Table (online only). Mouse plasma levels of cytokines after vein graft implantation (mean ± standard error of the mean; pg/mL)

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL079135, 1R01HL079135-06S1, and T32HL007734), the American Heart Association (12GRNT9510001), and the Carl and Ruth Shapiro Family Foundation.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS Conception and design: BN, CO Analysis and interpretation: BN, PY, MT, SH, TJ, CO Data collection: BN, PY, MT, SH, TJ Writing the article: BN, PY, CO Critical revision of the article: BN, PY, MT, SH, TJ, CO Final approval of the article: BN, PY, MT, SH, TJ, CO Statistical analysis: BN, PY, MT, SH, TJ, CO Obtained funding: CO, BN Overall responsibility: CO BN and PY contributed equally to this article.

Author conflict of interest: none.

Additional material for this article may be found online at www.jvascsurg.org.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the JVS policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sabroe I, Parker LC, Dower SK, Whyte MK. The role of TLR activation in inflammation. J Pathol. 2008;214:126–35. doi: 10.1002/path.2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ridker PM, Silvertown JD. Inflammation, C-reactive protein, and atherothrombosis. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1544–51. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owens CD, Ridker PM, Belkin M, Hamdan AD, Pomposelli F, Logerfo F, et al. Elevated C-reactive protein levels are associated with postoperative events in patients undergoing lower extremity vein bypass surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.08.048. discussion: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vink A, Schoneveld AH, Meer JJ, van Middelaar BJ, Sluijter JP, Smeets MB, et al. In vivo evidence for a role of Toll-like receptor 4 in the development of intimal lesions. Circulation. 2002;106:1985–90. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000032146.75113.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creely SJ, McTernan PG, Kusminski CM, Fisher M, Da Silva NF, Khanolkar M, et al. Lipopolysaccharide activates an innate immune system response in human adipose tissue in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E740–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00302.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim F, Pham M, Luttrell I, Bannerman DD, Tupper J, Thaler J, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates vascular inflammation and insulin resistance in diet-induced obesity. Circ Res. 2007;100:1589–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.142851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischetti F, Candido R, Toffoli B, Durigutto P, Bernardi S, Carretta R, et al. Innate immunity, through late complement components activation, contributes to the development of early vascular inflammation and morphologic alterations in experimental diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2011;216:83–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karper JC, de Vries MR, van den Brand BT, Hoefer IE, Fischer JW, Jukema JW, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in human and mouse vein graft remodeling, and local gene silencing reduces vein graft disease in hypercholesterolemic APOE*3Leiden mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1033–40. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.223271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayashi C, Madrigal AG, Liu X, Ukai T, Goswami S, Gudino CV, et al. Pathogen-mediated inflammatory atherosclerosis is mediated in part via Toll-like receptor 2-induced inflammatory responses. J Innate Immun. 2010;2:334–43. doi: 10.1159/000314686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaebnick HW, Bandyk DF, Bergamini TW, Towne JB. The microbiology of explanted vascular prostheses. Surgery. 1987;102:756–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giles KA, Hamdan AD, Pomposelli FB, Wyers MC, Siracuse JJ, Schermerhorn ML. Body mass index: surgical site infections and mortality after lower extremity bypass from the national surgical. Quality Improvement Program 2005-2007. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takaoka M, Nagata D, Kihara S, Shimomura I, Kimura Y, Tabata Y, et al. Periadventitial adipose tissue plays a critical role in vascular remodeling. Circ Res. 2009;105:906–11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatterjee TK, Stoll LL, Denning GM, Harrelson A, Blomkalns AL, Idelman G, et al. Proinflammatory phenotype of perivascular adipocytes: influence of high-fat feeding. Circ Res. 2009;104:541–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun K, Kusminski CM, Scherer PE. Adipose tissue remodeling and obesity. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2094–101. doi: 10.1172/JCI45887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aghamohammadzadeh R, Withers S, Lynch F, Greenstein A, Malik R, Heagerty A. Perivascular adipose tissue from human systemic and coronary vessels: the emergence of a new pharmacotherapeutic target. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:670–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu P, Nguyen BT, Tao M, Campagna C, Ozaki CK. Rationale and practical techniques for mouse models of early vein graft adaptations. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:444–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu P, Nguyen BT, Tao M, Bai Y, Ozaki CK. Mouse vein graft hemodynamic manipulations to enhance experimental utility. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:2910–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piascik MT, Hrometz SL, Edelmann SE, Guarino RD, Hadley RW, Brown RD. Immunocytochemical localization of the alpha-1B adrenergic receptor and the contribution of this and the other subtypes to vascular smooth muscle contraction: analysis with selective ligands and antisense oligonucleotides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:854–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwaiberger AV, Heiss EH, Cabaravdic M, Oberan T, Zaujec J, Schachner D, et al. Indirubin-3′-monoxime blocks vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by inhibition of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling and reduces neointima formation in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:2475–81. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.212654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoch JR, Stark VK, Hullett DA, Turnipseed WD. Vein graft intimal hyperplasia: leukocytes and cytokine gene expression. Surgery. 1994;116:463–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoch JR, Stark VK, van Rooijen N, Kim JL, Nutt MP, Warner TF. Macrophage depletion alters vein graft intimal hyperplasia. Surgery. 1999;126:428–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang Z, Berceli SA, Pfahnl CL, Wu L, Goldman D, Tao M, et al. Wall shear modulation of cytokines in early vein grafts. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:345–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang Z, Shukla A, Miller BL, Espino DR, Tao M, Berceli SA, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and the early vein graft. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:169–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozaki CK. Cytokines and the early vein graft: strategies to enhance durability. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(Suppl A):A92–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang Z, Yu P, Tao M, Ifantides C, Ozaki CK, Berceli SA. Interplay of CCR2 signaling and local shear force determines vein graft neointimal hyperplasia in vivo. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3536–40. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muto A, Model L, Ziegler K, Eghbalieh SD, Dardik A. Mechanisms of vein graft adaptation to the arterial circulation: insights into the neointimal algorithm and management strategies. Circ J. 2010;74:1501–12. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faries PL, Marin ML, Veith FJ, Ramirez JA, Suggs WD, Parsons RE, et al. Immunolocalization and temporal distribution of cytokine expression during the development of vein graft intimal hyperplasia in an experimental model. J Vasc Surg. 1996;24:463–71. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(96)70203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuguchi T, Musikacharoen T, Ogawa T, Yoshikai Y. Gene expressions of Toll-like receptor 2, but not Toll-like receptor 4, is induced by LPS and inflammatory cytokines in mouse macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;165:5767–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin M, Katz J, Vogel SN, Michalek SM. Differential induction of endotoxin tolerance by lipopolysaccharides derived from Porphyromonas gingivalis and Escherichia coli. J Immunol. 2001;167:5278–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X, Coriolan D, Murthy V, Schultz K, Golenbock DT, Beasley D. Proinflammatory phenotype of vascular smooth muscle cells: role of efficient Toll-like receptor 4 signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1069–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00143.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin FY, Chen YH, Tasi JS, Chen JW, Yang TL, Wang HJ, et al. Endotoxin induces Toll-like receptor 4 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells via NADPH oxidase activation and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2630–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000247259.01257.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pryshchep O, Ma-Krupa W, Younge BR, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Vessel-specific Toll-like receptor profiles in human medium and large arteries. Circulation. 2008;118:1276–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.789172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig (online only). CD45 immunohistochemical analysis of day 28 mouse vein grafts. A, Representative image of normal saline suspended in pluronic F-127 gel (NS)-treated vein graft. B, Representative image of lipopolysaccharide suspended in pluronic F-127 gel (LPS)-treated vein graft. The hand-digitally drawn yellow lines delineate the internal elastic laminas of vein graft walls. Red arrows show the representative positive cells. Scale bar = 50 μm. C, Quantitative analysis based on CD45 immunohistochemical images. Values are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean. There is no statistical difference between two groups for the various vascular wall layers.

Supplementary Table (online only). Mouse plasma levels of cytokines after vein graft implantation (mean ± standard error of the mean; pg/mL)