Abstract

Objectives

To describe (1) the role of illustrated medication instructions in pharmacy practice, (2) the evidence for their use, and (3) our experience with their implementation.

Practice description

PictureRx is applicable to all pharmacy practice settings.

Practice innovation

PictureRx enables pharmacists to rapidly produce evidence-based, illustrated medication instructions that are well-understood by patients of all health literacy levels.

Results

PictureRx has been studied in a number of settings. The tool was successfully deployed at a busy, outpatient pharmacy; in a medical clinic for the underserved; and pilot-tested among elderly, community dwelling Medicare recipients. In each of these settings, PictureRx was received favorably by patients, pharmacists, and other health care providers. It improved patients’ satisfaction with the pharmacy and knowledge about their medications. Ongoing research is assessing whether PictureRx enhances medication management among Latinos.

Conclusion

PictureRx helps pharmacists address challenges related to low health literacy and can be implemented into a broad range of practices environments. Ongoing research will delineate the extent to which PictureRx reduces health disparities.

Keywords: Medication management, health literacy, Latinos, communication, illustrated medication instructions

Introduction

Poor adherence to treatment regimens is a major challenge for American healthcare. Research shows that as many as half of all patients do not adhere to their prescription drug regimens, leading to more than $100 billion in avoidable hospitalizations and 89,000 premature deaths annually.1 Suboptimal adherence also plays a role in perpetuating many health disparities.2 A number of ethnic groups, including Latinos, the fastest growing segment of the United States population, have significantly lower adherence to prescribed medications. 3,4,5 Although there are many reasons why patients do not take all of their medications as prescribed, evidence suggests that health literacy – or the constellation of skills needed to effectively function in the health care environment – plays an important role.6 Research demonstrates that patients with inadequate health literacy skills have greater difficulty identifying and managing their own medications,7 and that they may have lower medication adherence.8–10

According to the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), 14% of adult Americans have below basic health literacy skills and 22% have basic skills.11 Average health literacy levels are lower among certain groups, including adults who have not completed high school, live below the poverty level, or speak English as a second language. Latinos have lower average health literacy scores than any other racial or ethnic group; fully 41% of Latinos scored at the below basic level, and 25% scored at the basic level on the NAAL. In addition to health literacy-related barriers, many Latinos also face language-related difficulties as they attempt to navigate the U.S. health care system. A large percentage of the Latino community speaks only Spanish (19%) or has limited English proficiency (55%).12

Understanding prescription drug information is not only a challenge for the millions of adults with low health literacy or limited English proficiency. The average consumer struggles to understand information typically found on prescription drug labels and information leaflets. Research demonstrates that the quality of prescription drug information is poor, with prescription drug labels,13,14 auxiliary warning labels,15 and other materials, such as consumer medication information leaflets16,17 and FDA medication guides,18 all suffering from poor design and readability, thus limiting their utility. Many patients rely on verbal counseling, but research shows that, unfortunately, this too is often suboptimal and typically does not meet the needs of patients with limited English proficiency or low health literacy.19–21

Patient-centered medication lists and illustrated medication instructions may be able to address some of these challenges.22 Providing patients with clearer instructions, in their preferred language, and supported by illustrations, has great potential to improve patients’ knowledge, satisfaction, and adherence.22,23 Such tools may be particularly valuable for patients who have low health literacy or limited English proficiency, because they are at greater risk for poor communication in clinical encounters.24 Here we describe our experience with PictureRx, a tool for pharmacists and other health care providers to develop illustrated medication instructions.

PictureRx Overview

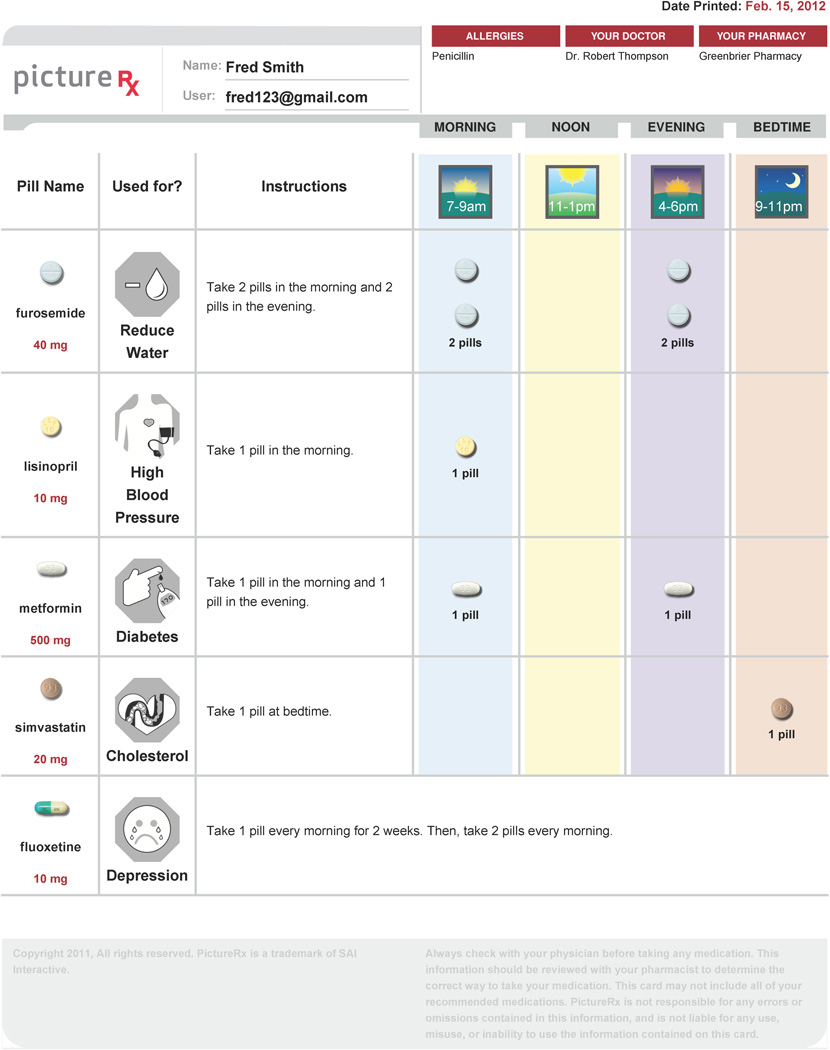

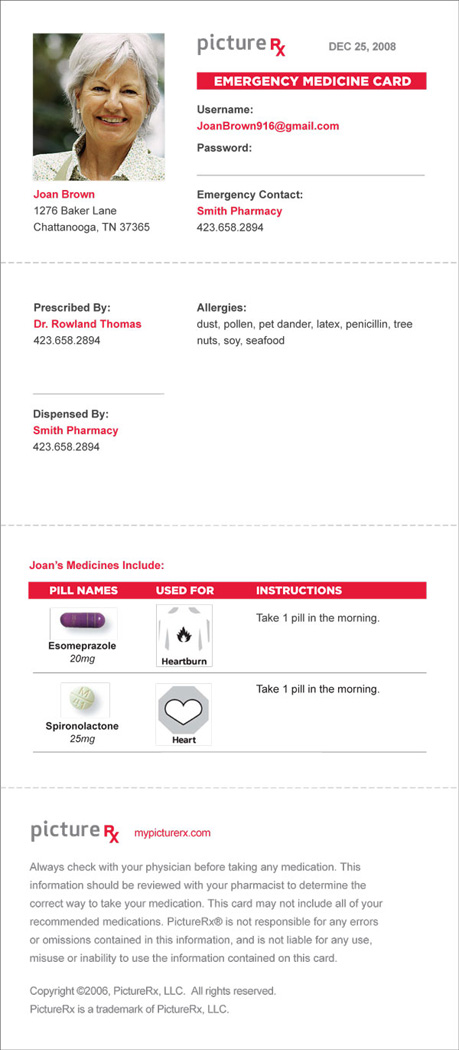

PictureRx is an internet-based technology that generates illustrated, patient-centered medication lists. PictureRx cards convey, in a daily medication schedule, the following essential information that patients should understand about each medication in their regimen: the name, dose/strength, frequency, purpose, and special instructions (Figure 1). The cards intentionally do not provide the full range of information commonly found on package inserts, because research has proven that these are poorly designed and understood.14,17 PictureRx also generates a wallet-sized medication reference card (Figure 2) that can be used in emergency situations or as a personal medication record that patients can carry easily between health care providers to foster clear communication about the medication regimen. The wallet card contains the critical data elements recommended for inclusion in medication lists by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and the panel convened for Continuity of Care in Medication Use Summit.25 This includes elements such as a patient’s name and date of birth; details about allergies and other medicine-related problems; a current list of medicines including the amount used, frequency of use and how each is taken; and information about who prescribed or recommended the medication. Instructions can be printed with both Spanish and English instructions, so that Latinos and their health care providers (respectively) could each understand the medication information.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

From its initial development in 2007, PictureRx was designed to improve medication management among vulnerable populations, with specific attention to patients who have low health literacy. The design of PictureRx cards is evidence-based, drawing on research and best practices for the creation of patient education materials,26–29 as well as the use of illustrations to convey medication instructions and other health-related information.22,23 PictureRx medication instructions use plain language and numerals, and refer to 4 specific times of day (morning, noon, evening, bedtime) when most medications can be taken.30 For example, PictureRx provides the instruction, “Take 1 pill in the morning and 1 pill in the evening” rather than “Take one tablet twice daily”). This approach has been described by others as the Universal Medication Schedule (UMS).30,31 Recent research has proven that this strategy leads to better patient comprehension.31

Creation of PictureRx Cards

PictureRx can been implemented both “automatically” and “manually.” In the automatic implementation, data from a pharmacy management system (PMS) is sent to a PictureRx server. Language processing rules have been developed to “translate” abbreviated medication information into UMS dosing schemes and standardized, patient-friendly language. A drug that might be entered as “1 T PO BID,” for example, would be translated as “Take 1 pill in the morning and 1 pill in the evening.” Pharmacists have the opportunity to subsequently review these instructions, edit them using the PictureRx user interface, and reprint them if necessary. To enhance the text instructions, a color picture of the medication is matched, according to the National Drug Code (NDC).

An alternative approach is for users to create an illustrated PictureRx card by entering basic information about the medication regimen and patient into a secure website. Instructions such as, “Take 1 pill in the morning,” are synthesized from information entered by the user and language processing rules developed by the project team. An interface for selecting pill images shows users the best matches from a comprehensive image library, narrowing the choices based on the amount of drug information entered (e.g., entering “lisinopril” shows all lisinopril images; further specifying 20mg shows only the different 20mg lisinopril tablets).

In both the automated and manual implementations, PictureRx automatically assigns the most common indication for each drug in the patient’s list and a corresponding icon. This mapping is performed through rules developed and reviewed by clinical pharmacists; users may change the drug indication and icon if desired. The icons were developed by a graphic designer in collaboration with the PictureRx team and input from consumers; they have been pilot tested among multiple patient groups to verify they are well-understood.

When drug information entry is complete, the site compiles this information to generate a full-color depiction of the daily medication regimen (Figure 1). Because the interface provides auto-complete functions and default selections to streamline the entry process, creating a PictureRx card typically requires less than 5 minutes in the manual approach, and less than 1 minute in the automated approach.

Experience with Implementation

Grady Health System

The initial PictureRx prototype was tested in the PILL study at Grady Memorial Hospital, an inner-city hospital where the prevalence of limited literacy skills is high.32 The PILL study was funded by a task order from AHRQ and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. This investigation evaluated a three-part intervention (PictureRx cards, clear health communication training for pharmacists,33 and automated telephone reminder calls to refill prescriptions34) that was intended to increase patients’ medication understanding and adherence through attention to health literacy. For the study, the project team integrated PictureRx with the Grady pharmacy management (Cerner, Kansas City, MO). When a study participant filled a prescription, a PictureRx card was automatically sent to a color printer, separate from that used to print medication labels and leaflets. Pharmacists used the PictureRx cards to facilitate counseling, and patients took the cards home as an educational aid. The evaluation included pharmacist focus groups, patient interviews and focus groups, and calculation of patients’ adherence to medication refills.

A total of 173 patients were enrolled in the intervention group and 102 patients in the control group. In the intervention group, refill adherence improved by 2 percentage points, while it worsened by 2 percentage points in the control group.35 This difference was not statistically different (p=0.4), though the study was not powered to detect a difference of this small size. In interviews and focus groups, intervention participants provided very positive feedback with regard to the study interventions. For example, patients indicated that PictureRx helped them “a lot” with each of the following aspects of medication management: remembering the appearance of each medicine (81.9%), the purpose of each medicine (81.9%), when to take each medicine (83.1%), and how much to take (83.1%).35 Patients also reported that their overall satisfaction with the pharmacy was affected “a lot” by PictureRx (79.3%).35 Importantly 80.5% of patients reported that PictureRx improved the counseling they received in the pharmacy “a lot,” and an additional 13.4% reported the counseling improved “a little.”35 Qualitative evaluation of focus group comments provided similar findings. Patients found the PictureRx cards to be a good tool for understanding their daily medication regimen, a good reminder to take the medications, and a useful reference that they could show to their health care providers to avoid confusion about what they were taking.36

In interviews with pharmacy staff, some challenges with the implementation were noted, especially early in the study period.36 These were primarily related to bugs in the initial version of the software, which were subsequently corrected. Despite these challenges, pharmacists were pleased overall with the PictureRx software and cards, and most felt that PictureRx served as an important counseling tool for their patients.36

PACE Program

In a subsequent pilot implementation, PictureRx cards were given to 20 older adults in New Orleans participating in the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), for which community-dwelling, Medicare recipients are eligible. Registered nurse case managers and social workers assisted in identifying and recruiting elders who regularly attended the health center, excluding those with severe dementia.

Participants each completed a baseline assessment of health literacy (Newest Vital Sign, NVS),37 medication self-efficacy (Self-Efficacy for Appropriate Medication use Scale, SEAMS),38 and self-reported adherence (Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale, ARMS).39 After each participant’s medications were reconciled by a pharmacist, a research nurse used the PictureRx website to generate PictureRx illustrated medication instructions. The PictureRx cards were printed on letter size paper in color on a laser printer and enclosed in a clear plastic sleeve for protection. Patients were oriented to the card and received brief medication counseling. They were asked to teach-back instructions to confirm comprehension and resolve any misunderstanding.40

Participants used the PictureRx cards for six weeks and completed another assessment of their medication self-efficacy and adherence. Participants also reported their experience in using the PictureRx cards and assessed the usefulness of the PictureRx cards in understanding medication purpose and dosing. Of 20 participants, 70% had a high likelihood of limited health literacy skills according to the NVS. Both self-efficacy and medication adherence significantly improved after provision of the PictureRx cards; (p < .001) and (p < .05), respectively. Participants rated the PictureRx cards as very easy to understand in terms of showing the medication purpose and dosing.41

How Pharmacists Can Implement PictureRx

As described previously PictureRx can be implemented both “automatically” and “manually.” Automatic implementation offers ease of use and standardization across all patients. However, this must be balanced by significant increases in cost and potential technical challenges given the range of pharmacy dispensing software. An alternative approach is “manual” implementation where patients can provide selected patients with a PictureRx card. Our previous experience suggests that patients who are elderly, take > 5 medications or who do not speak English are likely to benefit. In such an implementation, pharmacy staff identify patients who might benefit from the card and re-enter prescription information into a secure website after it has been filled. Although this creates redundancy in workflow, our experiences suggests that time to add a single medication is less than 30 seconds and information for each patient is stored so that the time required to create a card on subsequent fills is greatly reduced. In addition, this requires a systematic approach to identifying patients who may benefit or risk overlooking them. This can be easily done through several potential mechanisms ranging from simple reminders posted at the pharmacy workstations to “flags” that are programmed into pharmacy management systems so that when any patients meeting certain criteria arrive, the staff is notified.

The costs of automatic implementation depend on the difficulty of the software integration. Manual use of PictureRx is affordable and is generally less than $10 per patient per year with discounts available depending on patient volume. More information about both options is available at www.mypicturerx.com/info or by contacting the authors. Although patients can print illustrated medication instructions from MyMedSchedule (www.mymedschedule.com), to the best of our knowledge, PictureRx is the only system that is available to providers to produce evidence-based, illustrated medication instructions that utilize the Universal Medication Schedule. This includes features such as HIPAA compliance, advanced security, multi-user administrative interface, and a quick medication entry screen for “power users.”

Future features

Improvement of Icons

We are currently conducting several NIH-funded studies to test PictureRx among Latinos, as well as develop additional features and complementary features. One area of ongoing development and testing is the library of icons used to illustrate the drug indication. Published studies support the use of icons (together with text) to enhance understanding and recall of instructions.22,23 Much of the prior research has involved narrowly selected populations, a single icon, or a small group of icons.22 There are currently 93 indications and 80 associated icons used by PictureRx. Many of these images had previously been tested through focus groups with Latino and non-Latino patients to ensure to be sure they are well-understood cross culturally. Our present research in this area includes further testing of icons for 20 drug indications among Latinos and non-Latinos that were identified by the project team as critical (e.g. high burden of illness) or that may not be well-understood.

Development of Medication Labels

An additional area of ongoing work is the development of a multilingual, patient-centered, evidence-based prescription drug label. Following recent research which showed that traditional prescription drug labels are poorly understood by consumers,42–44 experts have recommended changes to the phrasing of instructions, formatting, and typography45 of labels. The PictureRx label design incorporates these recommendations, including plain language instructions (e.g., “Take 1 pill in the morning” instead of “Take once daily.”) and a 4-time-of-day format for medication instructions (Universal Medication Schedule). The label also includes an image of the medication and an icon for the drug indication. It can be printed in English only, or in both Spanish and English. We developed several versions of the label prototype, which we tested among focus groups of Latino and non-Latino patients, as well as pharmacists, to arrive at a final patient-centered design. The next step in this work is to conduct a randomized trial to assess the effect of this enhanced label on comprehension of prescription drug information.

Emerging Regulation

Regulatory agencies are taking steps to promote greater clarity in patient-provider communication. In 2010, the Joint Commission required that hospitals identify patients’ oral and written communication needs, including their preferred language, and communicate with patients in a way that meets those needs.46 More recently, the State of California enacted legislation that requires a standardized, patient-centered prescription drug label for all prescription drugs dispensed to patients in California.47 Similarly, the United States Pharmacopeia recently issued guidelines that describe prescription container label standards to promote patient understanding.48 These regulations require that pharmacists and healthcare organizations be increasingly aware of how effectively they communicate with patients and adopt new, patient-centered, evidence-based approaches. The use of PictureRx or comparable tools can help pharmacists meet these emerging regulations.

Conclusion

PictureRx was developed to more clearly communicate medication instructions to all consumers, particularly those with low health literacy. Our experience suggests that PictureRx can increase patient satisfaction, understanding of medication instructions, self-efficacy to take medications correctly, and self-reported adherence. PictureRx cards can be integrated into pharmacy practice in a way that minimizes disruptions to clinical workflow. The cards serve as a useful counseling tool by allowing pharmacists to review a patient’s full medication regimen, rather than having the information spread out across multiple bottles. Patients can subsequently take the card home and to medical appointments where it serves as a reminder and easy-to-read reference. PictureRx meets recently and emerging regulations which require pharmacies to provide drug information that is more easily understood by consumers. More widespread use of such strategies will be an important step toward fostering safe and effective medication use.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of United Neighborhood Health Services, Saint Thomas Family Health Centers, and Grady Memorial Hospital where much of the work presented here was done; and Elise Davidson and Jennie Mashburn, who provided assistance in preparation of this manuscript.

Funding Support:

PictureRx acknowledges research support through a National Center for Minority and Health Disparities SBIR Award R43 MD005805-01.

Footnotes

Disclosure:

Drs. Mohan, Boyington, and Kripalani are consultants to and hold equity in PictureRx, LLC. Mr. Riley is a paid employee of PictureRx, LLC.

References

- 1.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005 Aug 4;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2007 National Healthcare Disparities Report. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Feb 2008, AHRQ Pub. No. 08-0041; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gellad WF, Haas JS, Safran DG. Race/ethnicity and nonadherence to prescription medications among seniors: results of a national study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1572–1578. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0385-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raji MA, Kuo YF, Salazar JA, Satish S, Goodwin JS. Ethnic differences in antihypertensive medication use in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(2):209–214. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine. Health Literacy. A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kripalani S, Henderson LE, Chiu EY, Robertson R, Kolm P, Jacobson TA. Predictors of medication self-management skill in a low-literacy population. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(8):852–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gazmararian J, Kripalani S, Miller MJ, et al. Factors associated with medication refill adherence in cardiovascular-related diseases: a focus on health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:1215–1221. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Flum DR, Cornia PB, Koepsell TD. The impact of low health literacy on surgical practice. Am J Surg. 2004;188(3):250–253. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.04.005. 188(3):250-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalichman S, Ramachandran B, Catz S. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapies in HIV patients of low health literacy. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1999;14:267–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The Health Literacy of America's Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006-483) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed April 17, 2005];American FactFinder. Available at http://factfinder.census.gov.

- 13.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Shrank W, et al. To err is human: patient misinterpretations of prescription drug label instructions. Patient Educ Couns. 2007 Aug;67(3):293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shrank WH, Agnew-Blais J, Choudhry NK, et al. The variability and quality of medication container labels. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Sep 10;167(16):1760–1765. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Tilson HH, Bass PF, 3rd, Parker RM. Misunderstanding of prescription drug warning labels among patients with low literacy. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2006;63(11):1048–1055. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimberlin CL, Winterstein AG. [Accessed February 15, 2009];Expert and Consumer Evaluation of Consumer Medication Information-2008. Final Report to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Food and Drug Administration. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/CDER/news/CMI/default.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shrank WH, Avorn J. Educating patients about their medications: the potential and limitations of written drug information. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2007;26(3):731–740. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Shrank WH, Neuberger M, Parker RM. A critical review of FDA-approved Medication Guides. Patient Educ Couns. 2006 Sep;62(3):316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris LA, Tabak ER, Gondek K. Counseling patients about prescribed medication, 12-year trends. Medical Care. 1997;35(10):996–1007. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Praska JL, Kripalani S, Seright AL, Jacobson TA. Identifying and assisting low-literacy patients with medication use: a survey of community pharmacies. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;33(5):531–440. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G094. 39(9)1441-1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarn DM, Heritage J, Paterniti DA, et al. Physician communication when prescribing new medications. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166(17):1855–1862. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz MG, Kripalani S, Weiss BD. Use of pictorial aids in medication instructions: a review of the literature. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2006;63:2391–2397. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Houts PS, Doak CC, Doak LG, Loscalzo MJ. The role of pictures in improving health communication: A review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Education & Counseling. 2006;61(2):173–190. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arthur SA, Geiser HR, Arriola KR, Kripalani S. Health literacy and control in the medical encounter: a mixed-methods analysis. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009 Jul;101(7):677–683. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30976-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Executive summary of the Continuity of Care in Medication Use Summit. Am. J. Health. Syst. Pharm. 2008;65:e3–e9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Office of Communication. Simply Put. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Co.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kripalani S. The write stuff. Simple guidelines can help you write and design effective patient education materials. Texas Med. 1995;91:40–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arditi A. [Accessed February 9, 2009];Making Text Legible: Designing for People with Partial Sight. Available at: http://www.lighthouse.org/accessibility/legible. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolf MS, Curtis LM, Waite K, et al. Helping patients simplify and safely use complex prescription regimens. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Feb 28;171(4):300–305. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Curtis LM, et al. Effect of standardized, patient-centered label instructions to improve comprehension of prescription drug use. Med Care. 2011 Jan;49(1):96–100. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f38174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams MV, Parker RM, Baker DW, et al. Inadequate functional health literacy among patients at two public hospitals. JAMA. 1995;274(21):1677–1682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kripalani S, Jacobson KL. (Curriculum guide prepared under contract No. 290-00-0011 T07.) AHRQ publication No. 07(08)-0051-1-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. Oct, Strategies to improve communication between pharmacy staff and patients. A training program for pharmacy staff. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/pharmlit/pharmtrain.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobson KL, Gazmararian JA, McMorris KJ, Kripalani S. Automated telephone reminders: a tool to help refill medicines on time. AHRQ Publication No. 08-M017-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Feb, Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/callscript.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gazmararian J, Jacobson KL, Pan Y, Schmotzer B, Kripalani S. Effect of a pharmacy-based health literacy intervention and patient characteristics on medication refill adherence in an urban health system. Ann Pharmacother. 2010 Jan;44(1):80–87. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blake SC, McMorris K, Jacobson KL, Gazmararian JA, Kripalani S. A qualitative evaluation of a health literacy intervention to improve medication adherence for underserved pharmacy patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(2):559–567. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005 Nov-Dec;3(6):514–522. doi: 10.1370/afm.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Risser J, Jacobson TA, Kripalani S. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Self-efficacy for Appropriate Medication Use Scale (SEAMS) in low-literacy patients with chronic disease. J Nurs Meas. 2007;15(3):203–219. doi: 10.1891/106137407783095757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kripalani S, Risser J, Gatti ME, Jacobson TA. Development and evaluation of the Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS) among low-literacy patients with chronic disease. Value Health. 2009 Jan-Feb;12(1):118–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, et al. Closing the loop. Physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):83–90. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin D. Paper presented at: Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing, Xi-Psi Chapter-At Large, Research Day; November 18, 2010. New Orleans: Loyola University; 2010. Health Literacy Medication Education Quality Improvement Project. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Curtis LM, et al. Effect of standardized, patient-centered label instructions to improve comprehension of prescription drug use. Med Care. 2011 Jan;49(1):96–100. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f38174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, 3rd, et al. Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(8):847–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, III, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med. December 19, 2006. 2006;145(12):887–894. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Medicine Io. Standardizing Medication Labels: Confusing Patients Less. Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: Institute of Medcicine of the National Academies; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Organizations JCoAoH. Approved: New and Revised Hospital EPs to Improve Communication. Joint Commission Persepctives. 2010;30(1):5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herold V. Order of Adoption: Specific Language to Add to Section 1707.5. In: Pharmacy Bo., editor. Vol Section 1707.5, Article 2, Division 17, TItle 16. Sacramento, CA: California Code of Regulations; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Becker S. Prescription Container Labeling. Pharmacopeial Forum. 2011;37(1):2–7. [Google Scholar]