Abstract

The capacity to monitor spatiotemporal activity of phospholipase C (PLC) isozymes with a PLC-selective sensor would dramatically enhance understanding of the physiological function and disease relevance of these signaling proteins. Previous structural and biochemical studies defined critical roles for several of the functional groups of the endogenous substrate of PLC isozymes, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), indicating that these sites cannot be readily modified without compromising interactions with the lipase active site. However, the role of the 6-hydroxy group of PIP2 for interaction and hydrolysis by PLC has not been explored, possibly due to challenges in synthesizing 6-hydroxy derivatives. Here, we describe an efficient route for the synthesis of novel, fluorescent PIP2 derivatives modified at the 6-hydroxy group. Two of these derivatives were used in assays of PLC activity in which the fluorescent PIP2 substrates were separated from their diacylglycerol products and reaction rates quantified by fluorescence. Both PIP2 analogues effectively function as substrates of PLC-δ1, and the KM and Vmax values obtained with one of these are similar to those observed with native PIP2 substrate. These results indicate that the 6-hydroxy group can be modified to develop functional substrates for PLC isozymes, thereby serving as the foundation for further development of PLC-selective sensors.

The phospholipase C (PLC) family of enzymes catalyze the hydrolysis of membrane-bound phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to form the second messengers, diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3).1 Diacylglycerol activates protein kinase C (PKC) while IP3 activates calcium channels leading to the release of Ca2+ from endothelial reticulum to cytosol.2 In addition, PLC action also regulates local PIP2 pools leading to changes in subcellular localization and/or function of a broad range of PIP2-interacting proteins, including numerous ion channels. Consequently, PLCs are essential signaling proteins that regulate diverse cellular processes, including proliferation3 and differentiation,4 vasculogenesis,5 and fertilization.6 Aberrant regulation of PLCs has been implicated in diseases including cancer,7–13 heart diseases,14 and neuropathic pain.15

The 13 mammalian PLC isozymes are broadly grouped into six families (−β, −γ, −δ, −ε, −ζ, −η) based on their sequence homologies and functions. Various extracellular stimuli activate different PLC isoforms through distinct mechanisms. For example, agonists of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) activate PLC-β isozymes through Gαq- and Gβγ-subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins, while PLC-γ activity is enhanced through phosphorylation promoted by receptor and non-receptor tyrosine kinases. In addition, PLC-ε and certain members of the PLC-β and PLC-γ subclasses of isozymes are activated by Ras,1 Rho,17 and Rac subfamilies of small GTPases.18 However, when, where, and how various PLC isoforms are activated under different extracellular stimuli are still not well understood. This is partly due to the lack of methods to monitor the spatiotemporal activities of cellular PLCs.

Standard, radioisotope-based assays are discontinuous and cannot be used to monitor the real-time dynamics of PLC activity in cells. Cell permeable dyes that increase in fluorescence upon binding calcium are also routinely used as complementary methods to monitor PLC activity. However, although such assays are simple and throughput is high, they are not a direct measure of PLC activity and often generate confounding data since other factors also contribute to intracellular calcium concentration.

With the long-term goal of spatiotemporal monitoring of inositol lipid signaling, we initiated studies to develop small molecule sensors of PLCs. Previous kinetic studies demonstrated that the 2-hydroxy (2-OH) in PIP2 is essential19–21 for its hydrolysis by PLCs and that 3-phosphoinositides are not PLC substrates.22 Similarly, removal of the phosphate group from the 4- or 5-OH positions resulted in derivatives that are poor substrates for PLCs. Furthermore, the stereochemistry of the d-myo-insoitol headgroup, but not the diacylglycerol side chain, was shown to be critical for effective PLC-mediated catalysis.23 Finally, alkyl substitutions at the sn-1 and sn-2 positions resulted in PIP2 molecules that still function as PLC substrates.24 In general, the longer the side chain, the more efficient the corresponding PIP2 derivative was for PLC-promoted hydrolysis.25 These results are supported by the crystal structure26,27 of the catalytic domain of PLC-δ1 in complex with IP3; the 1-, 4-, and 5-phosphates and the 2- and 3-hydroxyls of IP3 interact with PLC-δ1, and mutation of these interacting residues greatly reduced the capacity of PLC-δ1 to hydrolyze PIP2.28 Consequently, modifications of PIP2 to develop new PLC substrates have avoided targeting the inositol headgroup and have instead focused on the diacylglycerol side chain. For example, we29 and others30–33 have developed fluorogenic PLC reporters with modifications at the 1-phosphate to monitor PLC activity in vitro. However, these systems are unlikely to be optimal for studies in live cells since potential spatial information on PLC activity will be lost upon cleavage of the fluorophore from the PIP2 derivative.

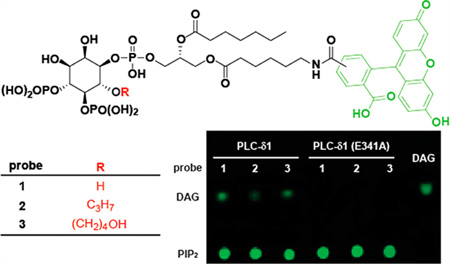

To our knowledge, selective modification of the 6-OH has not been explored despite extensive previous efforts synthesizing PIP2 analogues for novel functions and assays. The structure of PLC-δ1 bound to IP3 highlights a lack of direct interaction between the lipase active site and the 6-OH group, indicating that the 6-OH is solvent exposed and its modification in PIP2 is likely tolerated within the active site of PLCs. Consequently, we designed and synthesized three PIP2 derivatives (Figure 1) and investigated their capacity to be hydrolyzed by PLC-δ1. Probe 1 has a free 6-OH identical to endogenous PIP2 while probes 2 and 3 have modified 6-OH groups, with a propyl modification in 2 and an extended hydroxy in 3. The incorporation of a fluorescent group at the sn-1 position of the DAG side chain provides a sensitive detection of both the substrate and the product by fluorescence, thus avoiding the use of radioactive materials and providing a potential avenue for the use of realtime monitoring of phospholipase activity in cells with high spatiotemporal resolution and high throughput.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the PIP2 derivatives 1–3 as PLC substrates.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Kinetic Studies of Probes 1–3

Enzymatic Reactions

The fluorescent PIP2 derivatives were dissolved in water to make working solutions at 432, 324, 216, 108, 54, 32, 24, or 12 µM. To these solutions (20 µL) were added a 6X buffer (5 µL) that contains HEPES (300 mM, pH 7.2), KCl (420 mM), CaCl2 (17.8 mM), EGTA (18 mM), DTT (12 mM), and 3% cholate. The reaction was initiated by adding a solution (5 µL) that contains purified, full-length PLC-δ1 (0.05 or 0.1 ng/µL, final concentration) and BSA (1 mg/mL), and the reaction mixtures were incubated at 25 °C. At indicated time points, samples were taken out of the reaction mixtures with a multichannel pipet (1 µL) and spotted on TLC plates (Merck, Silica Gel-60). The TLC plates were then developed with CHCl3:MeOH:H2O (100:20:1) and scanned with a Typhoon 9400 Variable Mode Imager (λex/λem = 488 nm/520 nm). The fluorescence of DAG and PIP2 derivatives on the TLC plate was quantified with ImageQuant software (V.5.0).

Fluorescence Calibration and Reaction Rate Calculation

To a set of water solutions (20 µL) containing various concentrations (432, 324, 216, 108, 54, 32, 24, and 12 µM) of PIP2 derivative 1 was added the 6X buffer solution (5 µL) as defined previously and a PLC solution (5 µL) containing purified, full-length PLC-δ1 (10 ng/µL, final concentration) and BSA (1 mg/mL). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 25 °C for 2 h to completely convert probe 1 to DAG. As a control, the reactions were also carried out in the presence of BSA (PLC free). These two sets of reaction mixtures were spotted on TLC plates which were subsequently developed and the fluorescence was quantified. The fluorescence was plotted against concentration for probe 1 or DAG. The slope of the plot for probe 1 was 0.66-fold of that for DAG. Consequently, the amount of DAG that was generated from the reaction was calculated with the formula

where a = fluorescence of DAG and b = fluorescence of PIP2.

Kinetic Studies of Endogenous PIP2

A mixture of PIP2 (Avanti Polar Lipids) and 30 000 cpm of [3H]PIP2 (Perkin-Elmer) was dried under a stream of nitrogen and resuspended in assay buffer that contains HEPES (50 mM, pH 7.2), KCl (70 mM), EGTA (3 mM), DTT (2 mM), CaCl2 (2.96 mM), 0.5% cholate, and BSA (0.2 mg/mL). The resulting lipid stock was diluted to obtain final assay conditions with either 216, 144, 72, 36, 24, 16, 8, or 4 µM PIP2 in assay buffer (50 µL, final volume). Assays were initiated by the addition of purified, full-length PLC-δ1 (0.075 ng) in assay buffer (10 µL). After incubation at 25 °C for 10 min, reactions were stopped by the addition of 10% (v/v) trichloroacetic acid (200 µL) and 10 mg/mL BSA (100 µL) to precipitate proteins and uncleaved lipids. Centrifugation of the reaction mixture isolated soluble [3H] IP3, which was quantified using liquid scintillation counting.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

1. Synthesis of the Fluorescent Probes

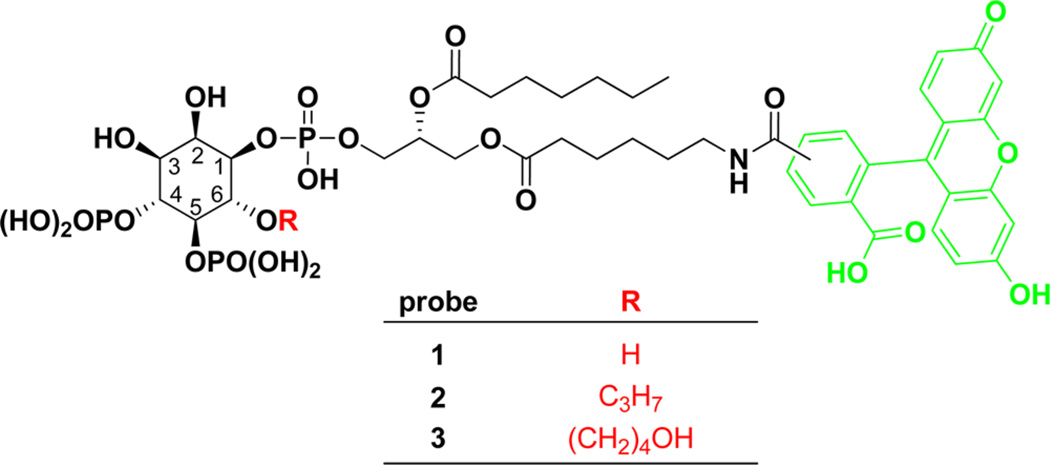

Fluorescent PIP2 derivatives with free 6-OH such as 1 have been used to image cellular PIP2 localization34 and as probes for metabolic enzymes such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K).35 Consequently, the synthesis of 1 follows the literature procedure.36–38 In contrast, PIP2 analogues with 6-OH selectively modified have not been reported and their syntheses are challenging. To synthesize the probe 2 (Scheme 1) with 6-OH group protected as its propyl ether, we started with the known inositol derivative 4. Alkylation of 4 with allyl bromide followed by deacetalization with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) generated 5 in 74% yield. The diol in 5 was subsequently protected as the corresponding methoxymethyl (MOM) ethers. Next, the corresponding methoxymethyl (MOM) ethers. Next, the tetraisopropyldisiloxane (TIPDS) group was removed by treating with hydrofluoride (HF) in CHCl3/CH3CN. The resulting hydroxy groups were phosphorylated to form 7 in a two-step sequence: first reacted with dibenzyl diisopropylphosphoramidite in the presence of tetrazole and then oxidized by 3-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (mCPBA). The tert-butyldiphenylsilyl (TBDPS) protection was removed by tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) to form alcohol 8, which was coupled to the diacylglycerol side chain 9 to form 10 in 90% yield through phosphorylation followed by oxidation with tert-butyl peroxide (t-BuOOH). To remove the MOM protective groups, compound 10 was treated with trimethylsilyl bromide (TMSBr) in CH2Cl2 followed by methanolysis. The benzyl protective groups were also partially removed during this process. Hydrogenolysis completed the deprotection of both benzyl and carbobenzyloxy (Cbz) groups and reduced the allyl to propyl group to form 11. Finally, the terminal amine was acylated with activated fluorescein 12 to generate the fluorescent PIP2 derivative 2 with 6-OH capped as a propyl ether. The overall yield of the synthesis was 37%.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Probe 2

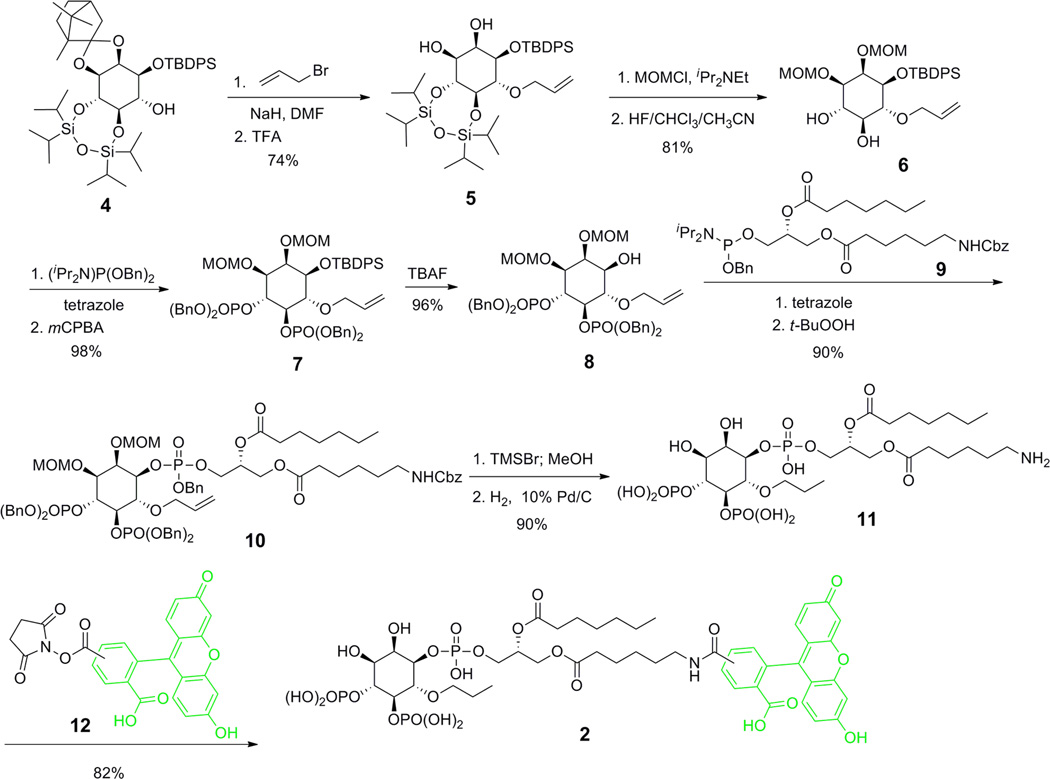

To synthesize the probe 3 (Scheme 2), olefin metathesis of 6 with MOM-protected allylic alcohol was carried out. We did not attempt to quantify the E/Z ratio although the formed double bond had predominantly the E configuration as judged by NMR. Instead, the olefin was directly subjected to hydrogenation to form 13. In a sequence that is analogous to the synthesis of probe 2, the diol 13 was used to generate probe 3. The overall yield of this sequence was 15%.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Probe 3

2. Thin-Layer Chromatography Coupled with Fluorescence Scanning as a New Assay for PLC Activity

The classical in-vitro assay of PLC activity requires the use of radioactive PIP2, particularly tritium-labeled PIP2, as the PLC substrate. To avoid the use of radioactive PIP2, 31P NMR has been used to monitor PLC-catalyzed reactions.39 However, the concentration of PIP2 has to be high (>0.5 mM) to obtain accurate measurement, and these techniques are not amenable to large numbers of samples. Existing fluorogenic 31,32 and luminescence-based33 reporters have the advantage of continuous monitoring of PLC activity with high sensitivity. However, these reporters typically replace the diacylglycerol unit connected to the 1-phosphate in PIP2, thereby limiting their utility to faithfully recapitulate intracellular events. In contrast, 6-OH analogues provide unexplored potential to produce useful biosensors of PLC activity in cells.

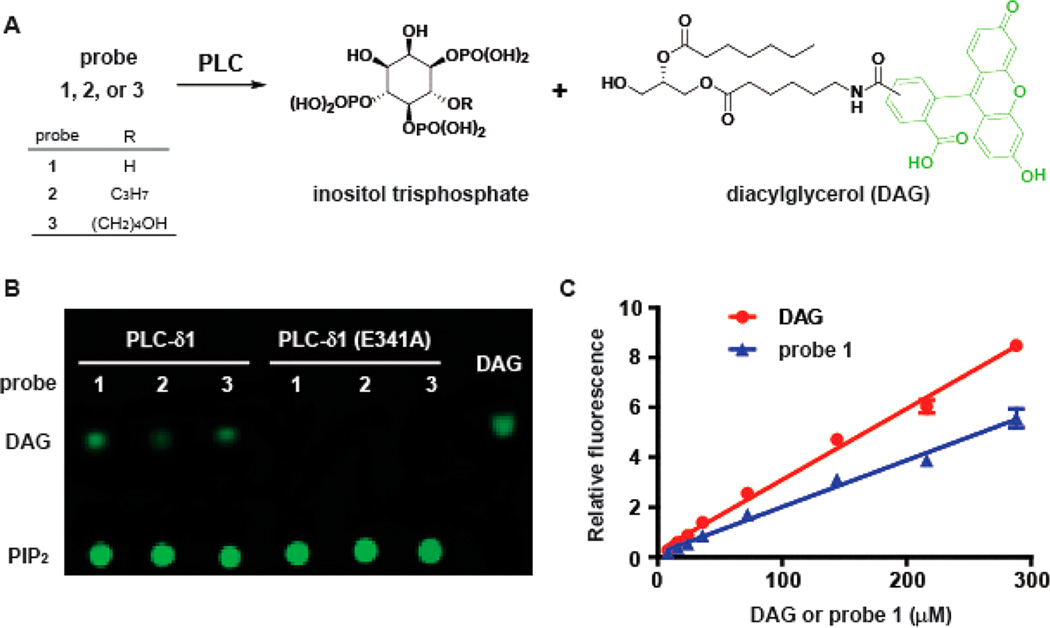

The fluorescent PIP2 derivative 1 has key structural features of endogenous PIP2 including an identical inositol phosphate headgroup and a diacylglycerol side chain. Derivative 1 and its expected PLC-dependent hydrolysis products (Figure 2A) are predicted to be readily separable by either TLC or column chromatography, and subsequent detection by fluorescence should provide a new assay for PLC activity. To validate this format, purified PLC-δ1 was used to hydrolyze probe 1. Based on sequence and structural similarities, the catalytic domain of PLC-δ1 is representative of the entire family of PLC isozymes. The enzymology of PLC-δ1 has also been extensively studied20,26,28,40–42, benefits from the unique structure of PLC-δ1 bound to IP3 within its active site. The purified enzyme was incubated with probe 1 at room temperature for 10 min, and the mixture was separated on TLC and detected by fluorescence. Fluorescence at the origin of application represents probe 1 and a second fluorescent component appeared as a function of increasing amounts of time during the initial incubation (Figure 2B). This new component was confirmed by LC-MS analysis to be the diacylglycerol derivatives predicted to be generated upon hydrolysis of probe 1 by PLC-δ1. When probe 1 was incubated with catalytically inactive PLC-δ1 (E341A),28 no new fluorescent components were formed (Figure 2B), indicating that the hydrolysis of 1 is dependent on the lipase activity of PLC-δ1.

Figure 2.

Validation of the TLC-fluorescence assay. (A) Probes 1–3 are cleaved by PLC-δ1 to form inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol (DAG) derivatives. (B) The separation of PIP2 derivatives 1–3 and their corresponding DAGs on thin-layer chromatography (TLC). The reaction mixture (1 µL) was spotted on the TLC plate and separated by CHCl3:MeOH:H2O (100:20:1). The fluorescent compounds were detected by a Typhoon 9400 variable mode imager (λex/λem = 488 nm/520 nm). (C) Plot of fluorescence versus concentration of DAG or probe 1.

Conditions were established to quantify the fluorescent DAG derivative formed during the reaction. Briefly, the linear plots of the fluorescence versus concentration for both 1 and the corresponding DAG product are shown in Figure 2C. The ratio of the slopes was used as the coefficient to normalize fluorescence readings for quantifications. Accordingly, 8% of probe 1 was converted to product in Figure 2B. Under identical conditions, 3% and 5% of probes 2 and 3 were converted to product, respectively. Like probe 1, probes 2 and 3 were not cleaved by catalytically inactive PLC-δ1 (E341A) suggesting that both are selective substrates for PLC-δ1.

3. Kinetic Studies of Probes 1–3 with PLC-δ1

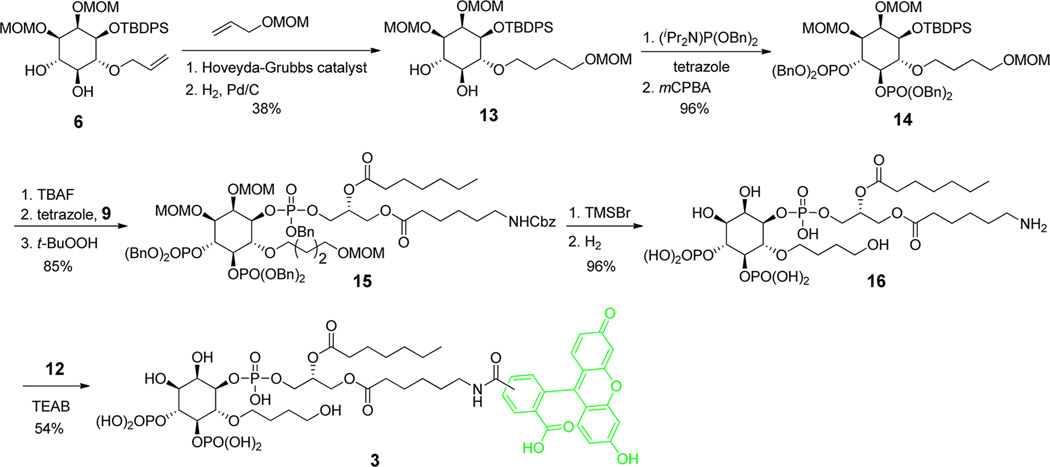

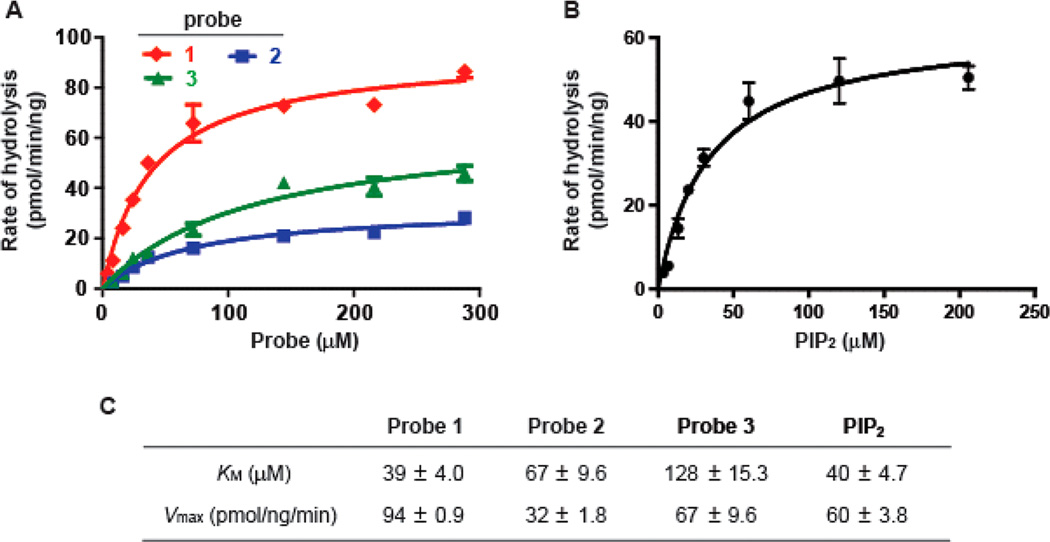

As highlighted in Figure 2B, probes 1–3 were cleaved by PLC-δ1 with different efficiencies. To further define these probes as PLC substrates for future development of PLC sensors, we carried out detailed kinetic studies to measure KM and Vmax of these probes in PLC-catalyzed reactions. For comparison, enzyme kinetics using PIP2 as the substrate were quantified as previously described43 by varying the bulk concentration of [3H]PIP2-containing vesicles.

To increase the efficiency and accuracy of the kinetic measurements, we carried out the experiments with probes 1–3 in a 96-well plate (Figure S1). At the indicated time, the samples were taken from reaction mixtures with a multichannel pipet and loaded directly onto the TLC plates. The fluorescent components in the reaction mixture were then separated and quantified by fluorescence. All the measurements were under initial rate conditions (Figures S2). KM and Vmax were then calculated by fitting the data to the Michaelis—Menten equation (Figure 3A,c,). The KM for probe 1 was 39 ± 4.0 µM with a Vmax of 94 ± 0.9 pmol/(ng min) while the KM for probe 2 was 67 ± 9.6 µM with a Vmax of 32 ± 1.8 pmol/(ng min). Capping of the 6-OH with a propyl group decreased Vmax and increased KM, suggesting that the modification at 6-OH might interfere with the key interactions of other substitutions in the inositol headgroup with PLC-δ1. In addition, the propyl group may increase the steric hindrance around the 1-phosphate, making the PLC-catalyzed nucleophilic addition of the 2-OH to the 1-phosphate a slower process. Interestingly, relative to probe 2, probe 3 further increased KM (128 ± 15.3 µM) while having a less detrimental effect on Vmax (67 ± 9.6 pmol/(ng min)), suggesting that increasing the length of the substitution at the 6-OH disrupts interactions with PLC-δ1 while the terminal hydroxy of the substitution may participate in substrate-assisted catalysis to facilitate phospholipase activity. In both cases, the KM and Vmax of 2 and 3 are within a 3-fold range of equivalent values for probe 1, which are similar to those for the endogenous PIP2 (Figure 3B,C). Consequently, modifying the 6-OH generate functional PIP2 derivatives that potentially can be applied to monitor PLC activity spatiotemporally.

Figure 3.

Kinetic studies of probes 1–3 or endogenous PIP2 with PLC-δ1. (A) The initial velocities of hydrolysis of 1, 2, or 3 at various concentrations were fitted to the Michaelis—Menten equation. (B) Hydrolysis rates of PIP2 at various concentrations were fitted to the Michaelis—Menten equation. (C) KM and Vmax of probes 1–3 and endogenous PIP2 with PLC-δ1.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we have developed an efficient synthesis to prepare PIP2 derivatives modified at the 6-hydroxy group, making it possible to explore the role of the 6-OH in PIP2 for PLC-catalyzed hydrolysis. Several of these derivatives have been characterized in a new TLC-based assay that features straightforward separation of products from the reaction mixture and sensitive detection for their capacity as substrates of PLC-δ1. These modifications at the 6-OH group result in derivatives that are excellent PLC substrates with marginally lower Vmax and higher KM values compared to the unmodified parent PIP2 derivative and endogenous PIP2. These results demonstrate that the 6-OH group can be modified for new functions, setting the stage for further development of sensors selective for PLC isozymes and useful for monitoring the spatiotemporal dynamics of these enzymes in living cells.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Stephanie Hicks for providing purified PLC-δ1 and Dr. Weigang Huang for helpful discussions.

Funding

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health (GM098894 and GM057391).

ABBREVIATIONS

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bi-sphosphate

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- DAG

diacylgly-cerol

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Experimental procedures and NMR spectra of key compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gresset A, Sondek J, Harden TK. The phospholipase C isozymes and their regulation. Subcell. Biochem. 2012;58:61–94. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-3012-0_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harden TK, Waldo GL, Hicks SN, Sondek J. Mechanism of activation and inactivation of Gq/phospholipase C-beta signaling nodes. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:6120–6129. doi: 10.1021/cr200209p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamura Y, Fukami K. Roles of phospholipase C isozymes in organogenesis and embryonic development. Physiology Bethesda. 2009;24:332–341. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00031.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cocco L, Faenza I, Follo MY, Billi AM, Ramazzotti G, Papa V, Martelli AM, Manzoli L. Nuclear inositides: PI-PLC signaling in cell growth, differentiation and pathology. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 2009;49:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao HJ, Kume T, McKay C, Xu MJ, Ihle JN, Carpenter G. Absence of erythrogenesis and vasculogenesis in Plcg1-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:933S–9341. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saunders CM, Swann K, Lai FA. PLCzeta, a sperm-specific PLC and its potential role in fertilization. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 2007:23–36. doi: 10.1042/BSS0740023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sala G, Dituri F, Raimondi C, Previdi S, Maffucci T, Mazzoletti M, Rossi C, Iezzi M, Lattanzio R, Piantelli M, Iacobelli S, Broggini M, Falasca M. Phospholipase Cgamma1 is required for metastasis development and progression. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10187–10196. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary JR, Angenendt P, Mankoo P, Carter H, Siu IM, Gallia GL, Olivi A, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Keir S, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, Busam DA, Tekleab H, Diaz LA, Jr, Hartigan J, Smith DR, Strausberg RL, Marie SK, Shinjo SM, Yan H, Riggins GJ, Bigner DD, Karchin R, Papadopoulos N, Parmigiani G, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikuta S, Edamatsu H, Li M, Hu L, Kataoka T. Crucial role of phospholipase C epsilon in skin inflammation induced by tumor-promoting phorbol ester. Cancer Res. 2008;68:64–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shepard CR, Kassis J, Whaley DL, Kim HG, Wells A. PLC gamma contributes to metastasis of in situ-occurring mammary and prostate tumors. Oncogene. 2007;26:3020–3026. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertagnolo V, Benedusi M, Brugnoli F, Lanuti P, Marchisio M, Querzoli P, Capitani S. Phospholipase C-beta 2 promotes mitosis and migration of human breast cancer-derived cells. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1638–1645. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cocco L, Manzoli L, Palka G, Martelli AM. Nuclear phospholipase C beta1, regulation of the cell cycle and progression of acute myeloid leukemia. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 2005;45:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bai Y, Edamatsu H, Maeda S, Saito H, Suzuki N, Satoh T, Kataoka T. Crucial role of phospholipase Cepsilon in chemical carcinogen-induced skin tumor development. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8808–8810. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinkes B, Wiggins RC, Gbadegesin R, Vlangos CN, Seelow D, Nurnberg G, Garg P, Verma R, Chaib H, Hoskins BE, Ashraf S, Becker C, Hennies HC, Goyal M, Wharram BL, Schachter AD, Mudumana S, Drummond I, Kerjaschki D, Waldherr R, Dietrich A, Ozaltin F, Bakkaloglu A, Cleper R, Basel-Vanagaite L, Pohl M, Griebel M, Tsygin AN, Soylu A, Muller D, Sorli CS, Bunney TD, Katan M, Liu J, Attanasio M, O'Toole JF, Hasselbacher K, Mucha B, Otto EA, Airik R, Kispert A, Kelley GG, Smrcka AV, Gudermann T, Holzman LB, Nurnberg P, Hildebrandt F. Positional cloning uncovers mutations in PLCE1 responsible for a nephrotic syndrome variant that may be reversible. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1397–1405. doi: 10.1038/ng1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi TJ, Liu SX, Hammarberg H, Watanabe M, Xu ZQ, Hokfelt T. Phospholipase C{beta}3 in mouse and human dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord is a possible target for treatment of neuropathic pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. SciUSA. 2008;105:20004–20008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810899105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harden TK, Hicks SN, Sondek J. Phospholipase C isozymes as effectors of Ras superfamily GTPases. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S243–S248. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800045-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seifert JP, Zhou Y, Hicks SN, Sondek J, Harden TK. Dual activation of phospholipase C-epsilon by Rho and Ras GTPases. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:29690–29698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805038200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harden TK, Sondek J. Regulation of phospholipase C isozymes by ras superfamily GTPases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2006;46:355–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Y, Perisic O, Williams RL, Katan M, Roberts MF. Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C delta1 activity toward micellar substrates, inositol 1,2-cyclic phosphate, and other water-soluble substrates: a sequential mechanism and allosteric activation. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11223–11233. doi: 10.1021/bi971039s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Essen LO, Perisic O, Katan M, Wu Y, Roberts MF, Williams RL. Structural mapping of the catalytic mechanism for a mammalian phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Bio chemistry. 1997;36:1704–1718. doi: 10.1021/bi962512p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruzik KS, Tsai MD. Toward the mechanism of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipases C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1994;2:49–72. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)82002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serunian LA, Haber MT, Fukui T, Kim JW, Rhee SG, Lowenstein JM, Cantley LC. Polyphosphoinositides produced by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase are poor substrates for phospholipases C from rat liver and bovine brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:17809–17815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruzik KS, Hakeem AA, Tsai MD. Are D- and L-chiro-phosphoinositides substrates of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C? Biochemistry. 1994;33:8367–8374. doi: 10.1021/bi00193a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rebecchi MJ, Eberhardt R, Delaney T, Ali S, Bittman R. Hydrolysis of short acyl chain inositol lipids by phospholipase C-delta 1. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:1735–1741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Mihai C, Kubiak RJ, Rebecchi M, Bruzik KS. Phosphorothiolate analogues of phosphatidylinositols as assay substrates for phospholipase C. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:1430–1439. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Essen LO, Perisic O, Cheung R, Katan M, Williams RL. Crystal structure of a mammalian phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C delta. Nature. 1996;380:595–602. doi: 10.1038/380595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams RL, Katan M. Structural views of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C: signalling the way ahead. Structure. 1996;4:1387–1394. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellis MV, James SR, Perisic O, Downes CP, Williams RL, Katan M. Catalytic domain of phosphoinositide- specific phospholipase C (PLC). Mutational analysis of residues within the active site and hydrophobic ridge of plcdelta1. J Biol. Chem. 1998;273:11650–11659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang W, Hicks SN, Sondek J, Zhang Q. A fluorogenic, small molecule reporter for mammalian phospholipase C isozymes. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011;6:223–228. doi: 10.1021/cb100308n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rose TM, Prestwich GD. Synthesis and evaluation of fluorogenic substrates for phospholipase D and phospholipase C. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2575–2578. doi: 10.1021/ol060773d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zaikova TO, Rukavishnikov AV, Birrell GB, Griffith OH, Keana JF. Synthesis of fluorogenic substrates for continuous assay of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. Bioconjugate Chem. 2001;12:307–313. doi: 10.1021/bc0001138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rukavishnikov AV, Zaikova TO, Birrell GB, Keana JF, Griffith OH. Synthesis of a new fluorogenic substrate for the continuous assay of mammalian phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:1133–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan M, Huang JC, Griffith OH, Keana JF, Volwerk JJ. A chemiluminescent substrate for the detection of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. Anal. Biochem. 1993;214:548–556. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozaki S, DeWald DB, Shope JC, Chen J, Prestwich GD. Intracellular delivery of phosphoinositides and inositol phosphates using polyamine carriers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:11286–11291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.210197897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang W, Jiang D, Wang X, Wang K, Sims CE, Allbritton NL, Zhang Q. Kinetic analysis of PI3K reactions with fluorescent PIP2 derivatives. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011;401:1881–1888. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5257-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen J, Profit AA, Prestwich GD. Synthesis of Photoactivatable 1,2-O-Diacyl-sn-glycerol Derivatives of 1-L-Phospha- tidyl-D-myo-inositol 4,5-Bisphosphate (PtdInsP(2)). and 3,4,5-Tri-sphosphate (PtdInsP(3)) J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:630S–6312. doi: 10.1021/jo960895r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kubiak RJ, Bruzik KS. Comprehensive and uniform synthesis of all naturally occurring phosphorylated phospha-tidylinositols. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:960–968. doi: 10.1021/jo0206418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bruzik KS, Tsai MD. Efficient and Systematic Syntheses of Enantiomerically Pure and Regiospecifically Protected Myoinositols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:6361–6374. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts MF, Redfield AG. High-resolution 31p field cycling NMR as a probe of phospholipid dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13765–13777. doi: 10.1021/ja046658k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng HF, Jiang MJ, Chen CL, Liu SM, Wong LP, Lomasney JW, King K. Cloning and identification of amino acid residues of human phospholipase C delta 1 essential for catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:5495–5505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lomasney JW, Cheng HF, Wang LP, Kuan Y, Liu S, Fesik SW, King K. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate binding to the pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C-delta1 enhances enzyme activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:25316–25326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yagisawa H, Sakuma K, Paterson HF, Cheung R, Allen V, Hirata H, Watanabe Y, Hirata M, Williams RL, Katan M. Replacements of single basic amino acids in the pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C-delta1 alter the ligand binding, phospholipase activity, and interaction with the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:417–424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Y, Sondek J, Harden TK. Activation of human phospholipase C-eta2 by Gbetagamma. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4410–4417. doi: 10.1021/bi800044n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.