Summary

En route to the neocortex, interneurons migrate around and avoid the developing striatum. This is due to the chemorepulsive cues of class 3 semaphorins (Sema3A and Sema3F) acting through neuropilin and plexin co-receptors expressed in interneurons. In a recent genetic screen aimed at identifying novel components that may play a role in interneuron migration, we identified LIM-kinase 2 (Limk2), a kinase previously shown to be involved in cell movement and in Sema7A-PlexinC1 signalling. Here we show that Limk2 is differentially expressed in interneurons, with a higher expression in the subpallium compared to cortex, suggesting it may play a role in their migration through the subpallium. Chemotactic assays, carried out with small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), revealed that Limk2-siRNA transfected interneurons are less responsive to Sema3A, but respond to Sema3F. Lack of responsiveness to Sema3A resulted in their aberrant invasion of the developing striatum, as demonstrated in brain slice preparations and in in utero electroporated mouse embryos with the same siRNAs. Our results reveal a previously unknown role for Limk2 in interneuron migration and Sema3A signalling.

Key words: Limk2, Interneuron, Migration

Introduction

Interneurons use a plethora of chemotactic cues to migrate along tortuous paths from their origins in the ganglionic eminences (GE) in the subpallium to the developing cortical plate (Métin et al., 2006). Within the subpallium, they migrate around and avoid the developing striatum before entering one of the tangential migratory streams within the neocortex. This is due to the chemorepulsive cues of class 3 semaphorins (Sema3A and Sema3F) acting through neuropilin and plexin receptors expressed in interneurons (Marín et al., 2001; Hernández-Miranda et al., 2011). In a recent genetic screen aimed at identifying novel molecules that may play a role in cortical interneuron migration (Faux et al., 2010), we identified high levels of expression of LIM-kinase 2 (Limk2) in the subpallium. LIM-kinases 1 and 2 are closely related proteins composed of two N-terminal LIM domains and a C-terminal kinase domain (Maekawa et al., 1999; Ohashi et al., 2000). The LIM domains are protein-binding motifs frequently found in cytosolic proteins that interact with the actin cytoskeleton (Bach, 2000). Following ligand binding and activation of the signalling cascade, Limks phosphorylate the actin-depolymerising protein Cofilin, leading to actin cytoskeletal reorganisation (Arber et al., 1998), ultimately resulting in changes in cell movement. In dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons, phosphorylation of Cofilin by Limk1 has been shown to be necessary for Sema3A-induced growth cone collapse (Aizawa et al., 2001). However, to date, no functional role has been proposed for Limk2 in the forebrain.

In the present study, we investigated the potential function of Limk2 in cortical interneuron development, focusing on their migration. We first confirmed that medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) cells express higher levels of Limk2 compared to cortical interneurons. We then performed siRNA knockdown experiments in dissociated MGE cells, in brain slice preparations and in mouse embryos and found that lack of Limk2 renders interneurons insensitive to the repulsive action of Sema3A, resulting in their aberrant migration through the striatum. Further, we established that Limk2 appears to mediate the response of migrating interneurons to Sema3A by interacting with PlexinA1. Our findings reveal a novel role for Limk2 in cortical interneuron migration and in Sema3A signalling.

Results and Discussion

To confirm the expression of Limk2 in interneurons, we first performed in situ hybridisation in coronal sections from E13.5–E15.5 mice. These preparations showed expression of Limk2 in the striatum, mantle zone of the GE, preoptic area and along the paths of migrating interneurons in the cortex (Fig. 1A,C). This pattern of expression matched the presence of Lhx6, a marker of GABAergic cells in the subpallium and pallium (Fig. 1B,D). Then, using immunohistochemistry in dissociated GAD67-GFP MGE cultures at E13.5, we observed extensive co-localisation between Limk2 and GAD67-GFP (Fig. 1F–H). Quantitative analysis of MGE- and cortical cell cultures at E13.5 and E15.5 showed >90% co-expression (Fig. 1I). Previous studies had reported that nearly all cortical interneurons contain high levels of GAD67 (Tanaka et al., 2006), unlike striatal cells that preferentially express GAD65 (Feldblum et al., 1993). To assess whether striatal neurons express Limk2, we co-immunostained dissociated E15.5 striatal cultures for the transcription factor FOXP2, a marker of these cells in embryonic life (Takahashi et al., 2003) and Limk2. These experimental showed the vast majority of striatal neurons do express Limk2 (Fig. 1E). Further, MGE cultures revealed higher levels of Limk2 expression compared to cortical preparations as assessed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1J) and Western blot (Fig. 1K,L), thus confirming our earlier observations (Faux et al., 2010).

Fig. 1. Limk2 expression in interneurons.

(A–D) In situ hybridisation on coronal sections from E13.5 (A,B) and E15.5 (C,D) mice with Limk2 (A,C) and Lhx6 (B,D) probes. (E) Limk2 (red) and FOXP2 (Green) co-immunohistochemistry in E15.5 striatal cultures. (F–H) Limk2 immunohistochemistry in E13.5 dissociated GAD67-GFP MGE cultures. (I) Quantification of the extent of co-localisation between GAD67-GFP and Limk2 in E13.5 and E15.5 dissociated cultures. (J) Limk2 immunohistochemistry on FACS E13.5 MGE- and cortical GAD67-GFP cells. (K,L) Immunoblots of Limk2 expression in FACS E13.5 and E15.5 MGE- and cortical GAD67-GFP cells (K) and quantification (L) showing lower level of expression in the latter. Scale bars: A, 200 µm; E,F,J, 25 µm. Cx, cortex; CP, cortical plate; LGE, lateral ganglionic eminence; MGE, medial ganglionic eminence; POA, preoptic area; PPL, preplate layer; Str, striatum; WB, Western blot. **P<0.001.

Loss of Limk2 function modulates interneuron responsiveness to Sema3A

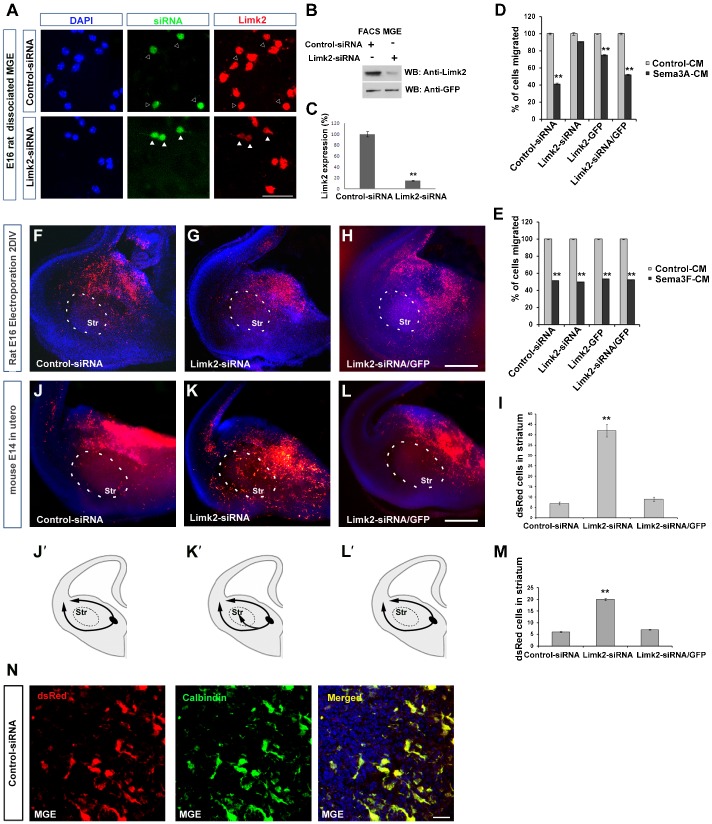

Previous studies have shown roles for Limks in Sema7A-PlexinC1 signalling in human melanocytes (Scott et al., 2009) and in Sema3A-induced growth cone collapse in DRG neurons (Aizawa et al., 2001). Given the high level of expression of Limk2 in MGE derived interneurons and the important roles Sema3A/Sema3F play in their migration through the subpallium (Marín et al., 2001), we wanted to assess its function in this process. To achieve this, we downregulated its expression using small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). We first established that transfection of MGE cells with Limk2-siRNA significantly reduced Limk2 protein levels (Fig. 2A–C). We then transfected MGE cells with siRNAs or the overexpressing construct (Limk2-GFP) and, using the Boyden chamber assay, assessed their response to Sema3A and Sema3F (Fig. 2D,E). Cells transfected with either control-siRNA or Limk2-GFP responded to Sema3A and Sema3F, confirming previous observations (Hernández-Miranda et al., 2011). Interestingly, while Limk2-siRNA transfected cells responded to Sema3F, they were refractory to Sema3A (Fig. 2D,E). To rescue Limk2-siRNA function, we co-transfected with the Limk2 expression construct and observed similar levels of responsiveness to semaphorins as with control-siRNA.

Fig. 2. Lack of responsiveness to Sema3A by Limk2 knockdown in MGE cells.

(A) E16 rat MGE cells were transfected with control or Limk2-siRNA (GFP) constructs. In Limk2-siRNA, GFP+ cells showed reduced level of Limk2 protein (Red) (white arrowheads) compared to control cells (black arrowheads). (B) Immunoblots of FACS purified MGE cells transfected with control or Limk2-siRNA showing reduced levels of Limk2 in the latter. (C) Histogram illustrates efficient Limk2 knockdown. (D,E) Quantification of transfected rat E16 MGE cell migration in a Boyden's chamber containing Sema3A (D), Sema3F (E) or control-CM. (F–H) Migration of MGE cells in E16 rat brain slices electroporated with control-siRNA (F), Limk2-siRNA (G) or Limk2-siRNA/Limk2-GFP (H). (J–L) Migration of MGE cells in a mouse embryo electroporated in utero at E14 with control-siRNA (J), Limk2-siRNA (K) or Limk2-siRNA/Limk2-GFP (L). (I,M) Quantification of electroporated cells (dsRed+) entering the striatum following in vitro (I) and in vivo (M) electroporation. (J′–L′) Schematic representation of the migratory routes adopted by MGE cells electroporated with control-siRNA (J′), Limk2-siRNA (K′), and Limk2-siRNA/Limk2-GFP (L′). (N) Co-localisation of dsRed and Calbindin (yellow) in interneurons within the MGE of control-siRNA in utero electroporated embryo. MGE, medial ganglionic eminence (L′). Scale bars: A, 60 µm; H,L, 200 µm; N, 10 µm. Str, striatum; CM, conditioned media. **P<0.001.

The finding that loss of Limk2 function renders MGE cells significantly less responsive to Sema3A, prompted us to hypothesise that neurons lacking this gene would alter their migratory route through the subpallium. To test this hypothesis, we carried out electroporation of siRNA vectors into the MGE of E16 rat brain slices (n = >50 slices). We found that interneurons transfected with control-siRNA migrated for the most part around the striatum; while noticeably more Limk2-siRNA transfected cells appeared to enter this structure (Fig. 2F,G,I). Co-electroporation of Limk2-siRNA and Limk2-GFP rescued Limk2 function, and interneurons migrated around the striatum (Fig. 2H,I). To further confirm these findings, we carried out in utero electroporation of the MGE of E14 mouse embryos (n = 6 each type). Similar to the in vitro experiments, we observed that transfection of MGE cells with either control-siRNA or Limk2-GFP resulted in the vast majority of cells avoiding the striatum, while transfection with Limk2-siRNA alone showed significantly more transfected cells in this structure (Fig. 2J–M). Finally, we established that electroporated MGE cells were indeed interneurons as they all co-labelled with calbindin, a marker of embryonic interneurons (Anderson et al., 1997) (Fig. 2N). Thus, our data are in accordance with earlier findings that support the involvement of Limks in semaphorin signalling events (Aizawa et al., 2001) and, furthermore, point to a role for Limk2 in interneuron migration through the subpallium.

Reduced levels of PlexinA1 in Limk2 knockdown cells

The finding of aberrant migration of interneurons through the striatum following elimination of Limk2 is reminiscent of the effect resulting from knockdown of neuropilin receptors in this system (Marín et al., 2001). Thus, we examined Neuropilin/Plexin receptor levels in cells transfected with Limk2-siRNA and control vectors. We found that transfection of MGE cells with Limk2-siRNA resulted in a significant decrease in the levels of mRNA and protein for PlexinA1, but not neuropilins compared to controls (Fig. 3A–C).

Fig. 3. Reciprocal effects on expression levels of Limk2 and PlexinA1 knockdown.

(A) QPCR analysis of rat E16 MGE cells transfected with Limk2-siRNA, PlexinA1-siRNA or control constructs; PCR products are shown on the left. (B,C) Immunoblots of MGE cells transfected with Limk2-siRNA and PlexinA1-siRNA showed reduced levels of Limk2 and PlexinA1, but not neuropilins compared to controls. (D,E) Migration of MGE cells in an E14 mouse embryo electroporated in utero with control-siRNA (D) or PlexinA1-siRNA (E). (F) Quantification of electroporated cells (dsRed+) entering the striatum. (D′,E′) Schematic representation of the migratory routes adopted by MGE cells electroporated with control-siRNA (D′) and PlexinA1-siRNA (E′). Scale bar: E, 200 µm. Str, striatum; WB, Western blot. **P<0.001.

This observation suggests that Limk2 interacts with PlexinA1 in mediating its effect in semaphorin signalling. To assess whether the effect is reciprocal, we transfected MGE cells with PlexinA1-siRNA and observed a significant decrease in the levels of PlexinA1 and Limk2, with little or no effect in neuropilin levels (Fig. 3A–C). This is consistent with a recent study which demonstrated that silencing of PlexinC1 resulted in reduced levels of Limk2 in human melanocytes (Scott et al., 2009).

To assess whether PlexinA1 knockdown affects migration in vivo, we carried out in utero electroporation of the MGE of E14 mouse embryos with control-siRNA and PlexinA1-siRNA (n = 4 each group) (Fig. 3D–F). Similar to Limk2 knockdown experiments, we observed more electroporated cells in the striatum following silencing of PlexinA1 compared to control. These findings together indicate that there exists a direct and reciprocal interaction between Limk2 and PlexinA1. Downregulation of either molecule renders cells unresponsive to the chemorepulsion of Sema3A.

Morphology of migrating interneurons after inactivation of Limk2

Inhibition of Limk1/Limk2 activity was previously shown to reduce actin filament assembly in the peripheral region of the growth cone of chick DRG neurons, resulting in altered neurite extension (Endo et al., 2007). To determine whether interneuron morphology was affected by Limk2- or PlexinA1 knockdown, we quantitatively assessed morphological parameters of control- (n = 72), Limk2- (n = 77), PlexinA1-siRNA (n = 73) in utero transfected interneurons, and Limk2 rescue (n = 70) cells. This analysis revealed that knockdown of Limk2 and PlexinA1 significantly affected the morphology of MGE cells, as they displayed more neurites, but significantly reduced neurite lengths compared to control cells (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Altered morphology of migrating interneurons electroporated with Limk2- or PlexinA1-siRNA.

(A–D) Morphology of MGE cells in an E14 mouse embryo electroporated in utero with control-siRNA (A), Limk2-siRNA (B), Limk2-siRNA/Limk2-GFP (C) or with PlexinA1-siRNA (D). (E–G) Histograms representing morphological parameters of electroporated MGE cells. Scale bar: A, 50 µm. *P<0.01.

On their way to the neocortex, interneurons migrate around and avoid the developing striatum. This is due to the chemorepulsive cues of Sema3A and Sema3F acting through neuropilin and plexin co-receptors expressed in these cells. We have shown here, using chemotactic assays and in vitro and in vivo electroporation experiments, that Limk2 is involved in semaphorin signalling and, consequently, has a role in interneuron migration. Thus, the present work reveals a new component in the Sema3A signalling pathway, and provides a novel insight into the involvement of Limk2 in interneuron migration.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and institutional guidelines. Wild-type animals were C57BL/6J mice obtained from Charles River Ltd GAD67-GFP (Δneo) mice (Tamamaki et al., 2003) used in this study were maintained in C57BL/6J background. The day the vaginal plug was found was considered as embryonic day (E) 0.5. Time-mated pregnant Sprague Dawley albino rats, obtained from University College London Biological Services Unit, were also used in this study.

In situ hybridisation

These experiments were performed as described previously (Antypa et al., 2011).

siRNA constructs

Limk2 and PlexinA1 siRNA knockdown and control scrambled sequence constructs were generated by annealing two pairs of oligonucleotides: Limk2-knockdown sense, 5′-ACCGACGCACCTTACGCAAGAGTCTTCCTGTCAACTCTTGCGTAAGGT-GCGTTTTTC-3′; antisense, 5′-TGCAGAAAAACGCACCTTACGCAAGAGTTG-ACAGGAAGACTCTTGCGTAAGGTGCGT-3′; Limk2 control-scrambled sense, 5′-ACCGTCAGTACCCCGGATACGAACTTCCTGTCATTCGTATCCGGGGTACTGATTTTC-3′; antisense, 5′-TGCAGAAAATCAGTACCCCGGATACGAATGACA-GGAAGTTCGTATCCGGGGTACTGA-3′; PlexinA1-knockdown sense, 5′-TCTCGTGCCTTGGCTGCTCAACAACTTCCTGTCATTGTTGAGCAGCCAAG-CACCT-3′; anti-sense, 5′-CTGCAGGTGCCTTGGCTGCTCAACAATGACAGGA-AGTTGTTGAGCAGCCAAGGCAC-3′ and PlexinA1 control-scrambled sense, 5′-TCTCGTGCCTTGGATGCTCAACAACTTCCTGTCATTGTTGAGCATCCAAGGCACCT-3′; anti-sense, 5′-CTGCAGGTGCCTTGGATGCTCAACAATGACAGG-AAGTTGTTGAGCATCCAAGGCA-3′ together and cloning into the siSTRIKEU6HAIRPIN-HMGFP vector according to manufacturer's instructions (Promega).

In vitro focal electroporation

These experiments were performed as described previously (Friocourt et al., 2007).

In utero electroporation

In utero electroporation to the MGE was performed as described recently (Wu et al., 2011). Briefly, timed pregnant C57/BL6 mice at E14 were anaesthetised, their abdomen opened and the uterus exposed. DNA vectors (1 µg/µl, 2 µl; ratio 2:1 siRNA:DsRed; 2:2:1 Limk2-siRNA:Limk2-GFP:DsRed) were injected into the third ventricle of embryos through a glass micropipette and introduced into the ventricular zone of the MGE by delivering electric pulses (40 V, 50 ms, 4 Hz) through the uterus. The uterus was repositioned in the abdominal cavity, and the abdominal wall and skin were sewn up with surgical sutures. The embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at E16.

Quantification of electroporated cells in striatum

Rat brain slices and in utero electroporated mouse brains were embedded and cut at 20 µm with a Cryostat All electroporated cells present within the striatum of each section (n = 4 per electroporated rat-slice/mouse brain) were counted.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was carried out using a conventional protocol (Hernández-Miranda et al., 2011). Briefly, MGE and striatal cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes, and washed in PBS. MGE cells and coronal cryosections were blocked in a solution of 5% Normal Goat Serum (Vector Laboratories) (v/v) and 0.5% Triton X-100 (v/v) (Sigma) in PBS at room temperature for 2 hours. All antibodies used were obtained from Santa-Cruz Biotechnology unless stated otherwise. Subsequently, they were incubated in primary rabbit anti-Limk2 antibody (1:200), rabbit anti-calbindin (1:1500; Swant), rabbit anti-Forkhead box protein P2 (FOXP2) (1:700; Abcam), or rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000; Invitrogen) at room temperature for 2 hours or overnight. Sections were washed and incubated in goat anti-rabbit Alexa-Flour-594 (1:200; Invitrogen) or goat anti-rabbit Alexa-Flour-488 (1:200; Invitrogen) for 2 hours. They were then washed and incubated with 4′-6-Diamidino-2-Phenyllindole (DAPI, 1:20,000; Sigma).

Production of semaphorin conditioned media

Production of media was carried out as described previously (Hernández-Miranda et al., 2011).

Dissociated cell cultures

Cell cultures were prepared as described previously (Hernández-Miranda et al., 2011).

Chemotaxis assays

Chemotactic assays using the Boyden chamber were performed as described previously (Hernández-Miranda et al., 2011).

Fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS)

FACS was performed as described previously (Hernández-Miranda et al., 2011).

Quantitative real-time PCR (QPCR)

Quantitative PCR experiments were performed as described recently (Hernández-Miranda et al., 2011). Primers for QPCR were designed by SigmaGenosys as follows: β-actin (forward GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG; reverse CCAGTTGGTAACAA-TGCCATGT); Gapdh (forward ATGACATCAAGAAGGTGGTG, reverse CATACCAGGAAATGAGCTTG); Limk2 (forward GGATGCAATAAAGCAGAC-AAGC, reverse GTGTCCCCTCCTGATTCTCCT); Nrp1 (forward GGATGGATT-CCCTGAAGTTG; reverse TGGATAGAACGCCTGAAGAG); Nrp2 (forward GCTGGCTACATCACTTCCCC, reverse CAATCCACTCACAGTTCTGGTG); PlexinA1 (forward CAGCACAGACAACGTCAACAA, reverse GCTTGAAG-AGATCGTCCAACC).

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed as described previously (Hernández-Miranda et al., 2011). To assess the protein levels of GFP, Limk2, Nrp1, Nrp2, PlexinA1 and β-actin proteins, membranes were incubated with polyclonal antibodies: GFP (1:1000); Limk2 (1:1000); Nrp1 (1:1000); Nrp2 (1:1000); PlexinA1 (1:1000); and monoclonal β-actin antibody (1:500; Sigma) in 5% BSA-TBST, washed with TBST, and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000; Vector Laboratories). After intensive washing, the proteins were visualised with ECL detection reagent (GE Healthcare).

Digital image acquisition and processing

Images were collected using a Leica light microscope (DM5000B) or a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope. They were reconstructed and digitised with Photoshop CS4 software (Adobe Systems Incorporated).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed by GraphPad3 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). All data were reported as mean and standard error of the mean (SEM). The statistical significance between group means was tested by one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test (for multiple comparison tests). Significance was set at P≤0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Rahman for technical support and Drs Y. Yanagawa and K. Obata for the GAD67-GFP transgenic mice. This work was funded by Wellcome Trust Programme Grant 089775.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Aizawa H., Wakatsuki S., Ishii A., Moriyama K., Sasaki Y., Ohashi K., Sekine–Aizawa Y., Sehara–Fujisawa A., Mizuno K., Goshima Y.et al. (2001). Phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase is necessary for semaphorin 3A-induced growth cone collapse. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 367–373 10.1038/86011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S. A., Eisenstat D. D., Shi L., Rubenstein J. L. (1997). Interneuron migration from basal forebrain to neocortex: dependence on Dlx genes. Science 278, 474–476 10.1126/science.278.5337.474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antypa M., Faux C., Eichele G., Parnavelas J. G., Andrews W. D. (2011). Differential gene expression in migratory streams of cortical interneurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 34, 1584–1594 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07896.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber S., Barbayannis F. A., Hanser H., Schneider C., Stanyon C. A., Bernard O., Caroni P. (1998). Regulation of actin dynamics through phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase. Nature 393, 805–809 10.1038/31729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach I. (2000). The LIM domain: regulation by association. Mech. Dev. 91, 5–17 10.1016/S0925-4773(99)00314-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M., Ohashi K., Mizuno K. (2007). LIM kinase and slingshot are critical for neurite extension. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13692–13702 10.1074/jbc.M610873200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faux C., Rakic S., Andrews W., Yanagawa Y., Obata K., Parnavelas J. G. (2010). Differential gene expression in migrating cortical interneurons during mouse forebrain development. J. Comp. Neurol. 518, 1232–1248 10.1002/cne.22271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldblum S., Erlander M. G., Tobin A. J. (1993). Different distributions of GAD65 and GAD67 mRNAs suggest that the two glutamate decarboxylases play distinctive functional roles. J. Neurosci. Res. 34, 689–706 10.1002/jnr.490340612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friocourt G., Liu J. S., Antypa M., Rakic S., Walsh C. A., Parnavelas J. G. (2007). Both doublecortin and doublecortin-like kinase play a role in cortical interneuron migration. J. Neurosci. 27, 3875–3883 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4530-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández–Miranda L. R., Cariboni A., Faux C., Ruhrberg C., Cho J. H., Cloutier J. F., Eickholt B. J., Parnavelas J. G., Andrews W. D. (2011). Robo1 regulates semaphorin signaling to guide the migration of cortical interneurons through the ventral forebrain. J. Neurosci. 31, 6174–6187 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5464-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa M., Ishizaki T., Boku S., Watanabe N., Fujita A., Iwamatsu A., Obinata T., Ohashi K., Mizuno K., Narumiya S. (1999). Signaling from Rho to the actin cytoskeleton through protein kinases ROCK and LIM-kinase. Science 285, 895–898 10.1126/science.285.5429.895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín O., Yaron A., Bagri A., Tessier–Lavigne M., Rubenstein J. L. (2001). Sorting of striatal and cortical interneurons regulated by semaphorin-neuropilin interactions. Science 293, 872–875 10.1126/science.1061891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Métin C., Baudoin J. P., Rakić S., Parnavelas J. G. (2006). Cell and molecular mechanisms involved in the migration of cortical interneurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 894–900 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04630.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi K., Nagata K., Maekawa M., Ishizaki T., Narumiya S., Mizuno K. (2000). Rho-associated kinase ROCK activates LIM-kinase 1 by phosphorylation at threonine 508 within the activation loop. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 3577–3582 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott G. A., McClelland L. A., Fricke A. F., Fender A. (2009). Plexin C1, a receptor for semaphorin 7a, inactivates cofilin and is a potential tumor suppressor for melanoma progression. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 954–963 10.1038/jid.2008.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K., Liu F. C., Hirokawa K., Takahashi H. (2003). Expression of Foxp2, a gene involved in speech and language, in the developing and adult striatum. J. Neurosci. Res. 73, 61–72 10.1002/jnr.10638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamaki N., Yanagawa Y., Tomioka R., Miyazaki J., Obata K., Kaneko T. (2003). Green fluorescent protein expression and colocalization with calretinin, parvalbumin, and somatostatin in the GAD67-GFP knock-in mouse. J. Comp. Neurol. 467, 60–79 10.1002/cne.10905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka D. H., Maekawa K., Yanagawa Y., Obata K., Murakami F. (2006). Multidirectional and multizonal tangential migration of GABAergic interneurons in the developing cerebral cortex. Development 133, 2167–2176 10.1242/dev.02382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Esumi S., Watanabe K., Chen J., Nakamura K. C., Nakamura K., Kometani K., Minato N., Yanagawa Y., Akashi K.et al. (2011). Tangential migration and proliferation of intermediate progenitors of GABAergic neurons in the mouse telencephalon. Development 138, 2499–2509 10.1242/dev.063032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]