Abstract

We report a patient who presented to our hospital with unusual symptoms of non-specific complaints and uncontrolled hypertension. Acute cardiac tamponade was suspected from cardiomegaly on routine chest x-ray and confirmed with an echocardiogram. Analysis of the pericardial fluid and other laboratory data ruled out all the common causes except for hypothyroidism as a cause of cardiac tamponade. Tamponade results from increased intrapericardial pressure caused by the accumulation of pericardial fluid. The rapidity of fluid accumulation is a greater factor in the development of tamponade than absolute volume of the effusion. Hypothyroidism is a well-known cause of pericardial effusion. However, tamponade rarely develops owing to a slow rate of accumulation of pericardial fluid. The treatment of hypothyroidic cardiac tamponade is different from other conditions. Thyroxine supplementation is all that is necessary. Rarely, pericardiocentesis is needed in a severely symptomatic patient.

Background

We believe this case is important for several reasons:

Pericardial effusion is common; however, cardiac tamponade rarely occurs as a presenting manifestation of hypothyroidism.

Our patient did not present with typical symptoms of tamponade and severe hypothyroidism (hypotension, bradycardia and hypothermia).

Treatment required pericardiocentesis because of severe symptoms.

Very few cases of hypothyroidic cardiac tamponade have been reported and we believe this will provide a good review of the entity to the clinicians.

Case presentation

A 42-year-old woman, with a medical history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension for 3 years, was admitted to our hospital with chief complaints of generalised weakness, abdominal pain and episodic shortness of breath. She was taking ramipril and hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension and metformin and sitagliptin for diabetes mellitus. She denied chest pain, fever, chills, diaphoresis or palpitations. On admission, her blood pressure was elevated at 202/117 mm Hg and her apical heart rate was 74 beats/min and regular. Family history was non-contributory. She was afebrile and in no distress at the time of admission. Physical examination was remarkable for lethargy. Heart sounds were distant; there was no gallop or heart murmur. Bilateral leg oedema was present over the ankles and pretibial areas.

Investigations

Laboratory data on admission were remarkable for serum glucose of 219 mg/dl; complete blood count, all electrolytes and liver enzymes were within the normal range. Renal function tests were normal with a blood urea nitrogen level of 16 mg/dl and a creatinine level of 0.8 mg/dl. Chest x-ray (CXR) (figure 1) showed cardiomegaly. B-type natriuretic peptide level by radioimmunoassay following cartridge extraction was 42 pg/ml (20–77). Shortly after admission, she developed increasing respiratory distress and required intubation. Her blood pressure dropped to 80 mm Hg systolic after intubation. An emergency echocardiogram (figures 2–4) showed a large pericardial effusion with diastolic collapse of the right atrium, right ventricle, respiratory variation of mitral inflow and concentric left-ventricular hypertrophy with normal systolic function. Needle pericardiocentesis was performed and the pericardial fluid analysis showed glucose 171 mg/dl, red blood cells 125 000/mm3, white blood cells 4750/mm3 with 70% neutrophils, 28% lymphocytes and 2% monocytes; protein 6.2 g/dl. Pericardial fluid gram stain and cultures were negative. Pericardial fluid cultures for tuberculosis were negative. Pericardial fluid cytology was negative for malignant cells. Hypotension resolved after needle pericardiocentesis and she was admitted to the intensive care unit. Subsequent laboratory data showed total serum cholesterol of 273 mg/dl, triglycerides 166 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein 39 mg/dl and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol 201 mg/dl; HbA1C level was 9%; serum antinuclear antibody titres were negative; erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 32 mm/h; a Helper T-cell count was 641/μl and ratio of CD4 over CD8 was 2.63, suggestive of no evidence of HIV/AIDS; thyroid-stimulating-hormone level by chemiluminescence was 69.13 MIU/ml (0.40–5.50); total T4 by immunoassay 3 μg/dl(4.5–12); free T4 by chemiluminescence 0.4 ng/dl (0.8–1.8). Acute myocardial infarction was ruled out with measurements of serial creatine phosphokinase and troponin I levels. The echocardiogram was repeated 1 day later and still showed significant pericardial effusion with right ventricular collapse. The patient underwent surgical drainage of pericardial fluid with a pericardial window. She was placed on l-thyroxine. Her condition improved over the next 2 days. She was extubated and subsequently discharged home on l-thyroxine.

Figure 1.

Chest x-ray showing cardiomegaly.

Figure 2.

Echocardiogram showing diastolic collapse of the right atrium.

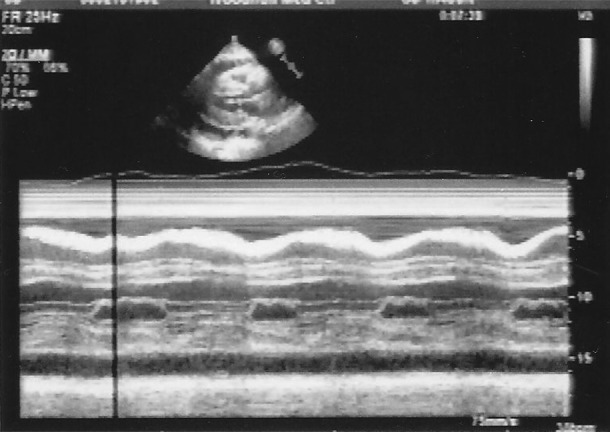

Figure 3.

Echocardiogram showing diastolic collapse of the right ventricle.

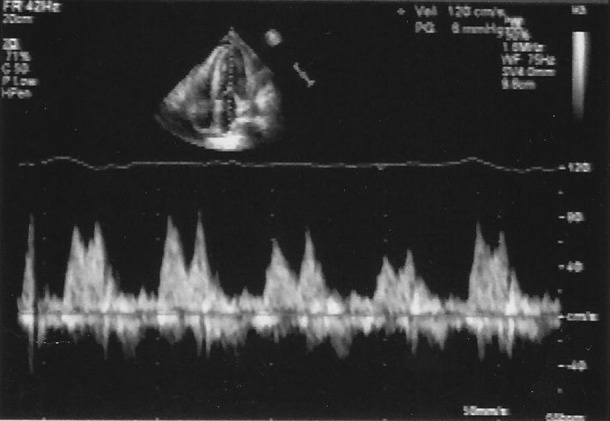

Figure 4.

Pulsus paradoxus.

All the common aetiologies for pericardial effusion such as infection, uraemia, collagen vascular diseases, malignancy, acute myocardial infarction, pericarditis or exposure to potential drugs were ruled out.

We attributed her cardiac tamponade to severe hypothyroidism as the only potential aetiological factor.

Discussion

Pericardial effusion is a well-known complication of hypothyroidism. The incidence was reported to be between 30 and 80%. However, recently, this has been refuted by Kabadi et al.1 In hypothyroidism, the accumulation of fluid in the pericardial space usually occurs very slowly, allowing enough time for the pericardium to stretch and, therefore, cardiac tamponade is extremely rare.

Pericardial effusion due to hypothyroidism was reported as early as 19182 and subsequently in 1925;3 however, cardiac tamponade due to hypothyroidism is very uncommon. Smolar et al,4 in 1976, did an extensive literature review and found only 13 reported cases of cardiac tamponade from hypothyroidism. In one study5 of 39 consecutive hypothyroid patients only 1 patient had a large pericardial effusion and 11 had mild effusions. In another study of 56 patients with cardiac tamponade,6 only 2 patients were found to be hypothyroidic. Only a handful of case reports have been published since then.5–11 Our patient is unique for several reasons. The usual presenting symptoms of cardiac tamponade such as hypotension, distant heart sounds and jugular-vein engorgement (Beck's triad) were absent initially. On the contrary, our patient was noted to be hypertensive which could be explained by profound vasoconstriction as a sympathetic response. Hypotension occurred after intubation which could be explained by decreased venous return and cardiac output from increased intrathoracic pressure related to mechanical ventilation. Also, our patient did not present with marked tachycardia which is usually present in cardiac tamponade. Normal heart rate in our patient could be due to hypothyroidism. Wang et al12 reviewed 36 patients over a 10-year period and reported that usual symptoms of cardiac tamponade may be absent in hypothyroidic cardiac tamponade. We ruled out all other aetiologies of tamponade. Hypothyroidism was the only abnormality that could explain the tamponade in our patient.

Normal pericardium is composed of visceral and parietal layers. Pericardial space is enclosed between these two layers and normally contains up to 50 ml of plasma ultra filtrate. Histologically, the pericardium is composed of compact collagen layers interspersed with elastin fibres. The abundance and orientation of collagen fibres is responsible for mechanical properties of the pericardium. The pericardium and pericardial fluid limit distention of the cardiac chambers and facilitate interaction and coupling of atria and ventricles. The pericardium also influences the qualitative and quantitative aspects of ventricular filling. The thin-walled right atrium and ventricle are affected more than the left. Pericardial fluid acts as a lubricant and prevents excessive friction with surrounding structures. The pericardial influences become significant when pericardial reserve volume (ie, the difference between unstressed pericardial volume and cardiac volume) is exceeded. Chronic stretching of pericardium results in stress relaxation so that slowly developing effusions do not produce tamponade.

Cardiac tamponade is a haemodynamic condition characterised by equal elevation of atrial and pericardial pressures, an exaggerated inspiratory decrease in arterial systolic pressure (pulsus paradoxus) and arterial hypotension. Occasionally, a heightened sympathoadrenal state produces systemic hypertension. Although the absolute intracardiac pressures are elevated, the transmural pressure (ie, cavitary diastolic pressure minus pericardial pressure) is zero or even negative. This results in diastolic collapse of the right atrium. The resultant decreased venous return is responsible for a severe drop in cardiac output. Hypotension develops when compensatory mechanisms are exhausted.

Aetiology of cardiac tamponade is similar to pericardial effusion. Common causes include infection, malignancy, metabolic factors, hypoalbuminaemia, collagen vascular disease, tuberculosis, traumatic, drug-induced, acute haemorrhage and postcardiac surgery. Clinical features depend on the rapidity of accumulation of fluid in the pericardial space and include shortness of breath, chest pain and dizziness. Venous pressure is elevated and arterial pressure is depressed. Pulsus paradoxus may be absent if severe hypotension is present. Classic findings include Beck's triad, that is, raised venous pressure, arterial hypotension and distant heart sounds.

ECG findings include low voltage in all leads and electrical alternans. CXR shows cardiomegaly. Echocardiography has been shown to be the best diagnostic test. In one study of 39 consecutive patients with hypothyroidism,5 4 patients with effusion showed no cardiomegaly on CXR; however, 12 patients with significant cardiomegaly on CXR showed no effusion on the echocardiogram. In another study of 33 patients,13 5 out of 13 patients with cardiomegaly on CXR did not show pericardial effusion on echocardiogram.

Treatment of cardiac tamponade depends on the haemodynamic state of the patient. Removal of even a small amount of pericardial fluid (about 50 ml) produces considerable haemodynamic and symptomatic improvement because of the steep pericardial pressure–volume relationship. Early tamponade with only mild haemodynamic compromise may be treated conservatively with close observation, fluid restriction and therapy aimed at the underlying cause. The majority of the cases will require a surgical drainage procedure. Catheter pericardiocentesis followed by surgical drainage with creation of a pericardial window, if effusion recurs, is a reasonable approach. Therapeutic measures that reduce venous filling pressures or effective cardiac output should be avoided as reported by Alsever et al.14 In pericardial effusions and tamponade due to hypothyroidism, various authors have noted recurrence of effusion after needle drainage of pericardial fluid8 11 and these should be anticipated. Thyroid replacement therapy is imperative and is often all that is needed in a large majority of these patients.

Learning points.

Although rare, pericardial effusion from hypothyroidism may present with tamponade.

Thyroxine supplementation is usually sufficient for treatment. In rare cases, a pericardial window is required for severe symptoms.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kabadi UM, Kumar SP. Pericardial effusion in primary hypothyroidism. Am Heart J 1990;120(6 pt 1):1393–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zondek H. Das myxodemherz (Article in German). Munch Med Wschr 1918;65:1180–3 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fahr G. Myxedema heart. J Am Med Assoc 1925;84:345–9 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smolar EN, Rubin JE, Avramides A, et al. Cardiac tamponade in primary myxedema and review of literature. Am J Med Sc 1976;272:345–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardisty CA, Naik DR, Munro DS. Pericradial effusion in hypothyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1980;13:349–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guberman BA, Fowler NO, Engel PJ, et al. Cardiac tamponade in medical patients. Circulation 1981;64:633–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Retnam VJ, Chichgar JA, Patkar LA, et al. Myxedema and pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade (a case report). J Postgrad Med 1983;29:188–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auguet T, Vazquez A, Nolla J, et al. Cardiac tamponade and hypothyroidism. Int Care Med 1993;19:241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma N, Jain S, Kumari S, et al. Hypothyroidism—an unusual case of cardiac tamponade. Aust NZ J Med 2000;30:731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rachid A, Caum LC, Trentini AP, et al. Pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade as a form of presentation of primary hypothyroidism. Arq Bras Cardio 2002;78:583–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karu AK, Khalife WI, Houser R, et al. Impending cardiac tamponade as a primary presentation of hypothyroidism: case report and review of literature. Endocr Pract 2005;11:265–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JL, Hsieh MJ, Lee CH, et al. Hypothyroid cardiac tamponade: clinical features, electrocardiography, pericardial fluid and management. Am J Med Sci 2010;340:276–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerber RE, Sherman B. Echocardiographic evaluation of pericardial effusion in myxedema; incidence and biochemical and clinical correlations. Circulation 1975;52:823–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alsever R, Stjernholm M. Cardiac tamponade in myxedema. Am J Med Sc 1975;269:117–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]