Abstract

Background

We evaluated the efficacy and safety of single-dose fosaprepitant in combination with intravenous granisetron and dexamethasone.

Patients and methods

Patients receiving chemotherapy including cisplatin (≥70 mg/m2) were eligible. A total of 347 patients (21% had received cisplatin with vomiting) were enrolled in this trial to receive the fosaprepitant regimen (fosaprepitant 150 mg, intravenous, on day 1 in combination with granisetron, 40 μg/kg, intravenous, on day 1 and dexamethasone, intravenous, on days 1–3) or the control regimen (placebo plus intravenous granisetron and dexamethasone). The primary end point was the percentage of patients who had a complete response (no emesis and no rescue therapy) over the entire treatment course (0–120 h).

Results

The percentage of patients with a complete response was significantly higher in the fosaprepitant group than in the control group (64% versus 47%, P = 0.0015). The fosaprepitant regimen was more effective than the control regimen in both the acute (0–24 h postchemotherapy) phase (94% versus 81%, P = 0.0006) and the delayed (24–120 h postchemotherapy) phase (65% versus 49%, P = 0.0025).

Conclusions

Single-dose fosaprepitant used in combination with granisetron and dexamethasone was well-tolerated and effective in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving highly emetogenic cancer chemotherapy, including high-dose cisplatin.

Keywords: chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, CYP3A4, fosaprepitant, single-dose, substance P

introduction

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is highly distressing and is a feared adverse event in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. Without adequate antiemetic treatment, >90% of patients experience CINV when given highly emetogenic chemotherapy (including cisplatin) [1]. Until recently, combination therapy with a 5-hydroxytryptamine type-3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonist and corticosteroid was the standard treatment in Japan. With the advent of aprepitant, a neurokinin type-1 (NK1) receptor antagonist, used in combination with the 5-HT3 antagonist and corticosteroid, further improvements in the antiemetic efficacy have been achieved. Current guidelines recommend this three-drug combination for the prevention of CINV in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy [2–4]. In this regimen, aprepitant (per os) is given for 3 days, and dexamethasone is given for 4 days.

Fosaprepitant is a water-soluble phosphoryl prodrug for aprepitant. When administered intravenously, fosaprepitant is rapidly converted to aprepitant [5]. Treatment with fosaprepitant (115 mg) has been initially approved in Western countries as an alternative to oral aprepitant (125 mg) on day 1 of a 3-day antiemetic regimen. Although current guidelines recommend 3-day dosing with aprepitant for the prevention of CINV, previous studies indicated that single-dose aprepitant conferred antiemetic effects for acute and delayed CINV [6, 7]. Recently, a phase 2 study suggested that a single-day regimen consisting of a higher dose of aprepitant plus palonosetron and dexamethasone was feasible and effective for the prevention of CINV in patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy [8]. Up to 150 mg of fosaprepitant can be administered without any significant prevalence of infusion-related adverse events [9]. A randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study comparing intravenous single-dose fosaprepitant with 3-day oral aprepitant, each combined with ondansetron and dexamethasone, was conducted to demonstrate that a single-dose fosaprepitant 150-mg regimen is non-inferior to a 3-day oral aprepitant (125 mg/80 mg/80 mg) regimen [10]. At the time when we decided to evaluate the antiemetic efficacy of fosaprepitant in Japan, aprepitant was not approved for clinical use in Japan. Therefore, we conducted a placebo-controlled, randomised, phase 3 study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of fosaprepitant in combination with granisetron and dexamethasone to prevent CINV in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy containing cisplatin at ≥70 mg/m2.

patients and methods

The study protocol was approved by the ethics review board of each institution. All the patients provided written informed consent to be enrolled in the study.

inclusion criteria

Patients aged ≥20 years who received cancer chemotherapy containing cisplatin (≥70 mg/m2) were included in this study. All patients were required to have an ECOG Performance Status of 0–2 and an estimated life expectancy of ≥3 months. They also had to meet the following criteria based on laboratory analyses: white blood cell count, ≥3000/mm3; neutrophil count, ≥1500/mm3; platelet count, ≥100 000/mm3; aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase, ≤2.5 × the upper limit of the normal range in the institution (ULN); total bilirubin, ≤1.5 × ULN; and creatinine, ≤1.5 × ULN.

exclusion criteria

To minimise confounding effects in the efficacy evaluation, certain patients were excluded from the study as follows: patients who would receive at least moderately emetogenic antitumour agent(s) [11] in combination with cisplatin at any point from 6 days before cisplatin dosing (day –6) to day 6 except for the day of cisplatin dosing; patients who would receive paclitaxel in combination with cisplatin; patients who had previously been treated with cisplatin without vomiting; and patients with a risk of vomiting for other reasons. Concomitant use of the following drugs was prohibited: all antiemetics other than fosaprepitant from 48 h before cisplatin dosing to day 6; CYP3A4 substrates and inhibitors from day –7 to day 15; and CYP3A4 inducers from week –4 to day 6. In addition, certain other patients were excluded from the study as follows: patients with a history of hypersensitivity to granisetron or dexamethasone phosphate; patients who had previously been treated with fosaprepitant or aprepitant; and pregnant (or potentially pregnant) and nursing women.

study design

This was a multicentre, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomised, parallel study conducted in 68 institutions in Japan. In the placebo group, the patients received intravenous administration of placebo, granisetron (40 μg/kg body weight), and dexamethasone phosphate (20 mg) on day 1, and dexamethasone phosphate (8 mg) on days 2 and 3. In the fosaprepitant group, patients received intravenous administration of fosaprepitant (150 mg), granisetron (40 μg/kg), and dexamethasone phosphate (10 mg) on day 1, dexamethasone phosphate (4 mg) on day 2, and dexamethasone phosphate (8 mg) on day 3. Aprepitant (the active form of fosaprepitant and a CYP3A4 inhibitor) is known to increase plasma dexamethasone concentrations when used in combination with dexamethasone (CYP3A4 substrate) [12, 13]. To achieve comparable plasma levels of dexamethasone in the fosaprepitant and placebo groups, the dose of dexamethasone in the fosaprepitant group was half of that in the placebo group on days 1 and 2. On day 1, a single intravenous dose of fosaprepitant or placebo was administered over 20–30 min beginning 1 h before the start of administration of the first moderately emetogenic or highly emetogenic antitumour agent (including cisplatin), and dexamethasone and granisetron were intravenously administered over ≤30 min starting 30 min before the administration of the first emetogenic antitumour agent. On days 2 and 3, dexamethasone was intravenously administered in the morning.

assessments

Patient self-assessment of drug efficacy was constantly evaluated from the start of administration of the first moderately emetogenic or highly emetogenic antitumour agent (including cisplatin) until the morning of day 6 (i.e. 120 h after the start of administration of the emetogenic agent). Vomiting was defined as at least one episode of emesis or retching. One episode of vomiting was distinguished from other episodes if emesis was not observed for ≥1 min. Patients were instructed to record the date and time of vomiting in a symptom diary. For nausea, patients were instructed to assess the most intense bout of nausea during the past 24-h period based on a four-point scale [0, none; 1, mild (food and water can be ingested); 2, moderate (only water can be ingested); 3, severe (neither food nor water can be ingested)]. Self-assessment of nausea was undertaken at around noon on days 2–6 and recorded in a symptom diary. For rescue therapy (defined as treatment with drug therapy to treat nausea/vomiting), the investigator or nurse recorded the date and time of therapy, name and dose of drug, and reason for use. The safety measures were adverse events, drug-related adverse events, general laboratory tests, body weight, vital signs, 12-lead electrocardiogram, and injection-site reaction, and were assessed until day 15. Toxicity grades were assessed using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (v3.0).

statistical analysis

On the assumption that the percentages of patients with a complete response would be 68% in the fosaprepitant group [calculated as the sample size-weighted mean from the results of a Japanese phase 2 study [14] and phase 3 studies conducted outside of Japan (studies 052 and 054) of aprepitant [15, 16]] and 50% (calculated from the results of the Japanese phase 2 study [14]) in the placebo group, a sample size of 155 patients per group was estimated to be required to provide a power of 90% for detecting a significant difference at a two-sided significance level of 5%, using the χ2 test. On the assumption that ∼10% of patients would be withdrawn or drop out of the study, a target sample size of 170 patients per group (340 patients in total) was selected. The primary end point was the percentage of patients with complete response (no emesis and no rescue therapy) in the overall phase. The percentages of patients with a complete response in the acute and delayed phases were assessed as secondary end points. Other secondary end points were the time to first episode of vomiting as well as the percentages of patients with complete protection (no emesis, no rescue therapy, and nausea of no more than mild severity); total control (no emesis, no rescue therapy, and no nausea); no emesis (including those who used rescue therapy); no rescue therapy; no nausea; and no significant nausea (no more than mild severity). The efficacy analysis was carried out on the modified intention-to-treat (ITT) population. The modified ITT population consisted of all randomised patients who met the main enrolment criteria; were treated with granisetron and dexamethasone phosphate (at least one dose); were treated with fosaprepitant or placebo; and were monitored at least once after treatment with the study drug. To compare the primary and secondary end points (other than the time to first episode of vomiting) between the fosaprepitant and placebo groups, the Mantel–Haenszel test was carried out after stratification for treatment, sex, presence or absence of at least moderately emetogenic antitumour agent used in combination with cisplatin, and presence or absence of previous treatment with cisplatin. For the time to first episode of vomiting, a Kaplan–Meier curve was plotted for each group, and a log-rank test carried out to compare the two groups. The safety analysis was carried out on all randomised patients who were treated with the study drug. For adverse events, drug-related adverse events, and injection-site reactions, the prevalence was calculated for each group, and the χ2 test was carried out for comparisons between the two groups.

results

patients

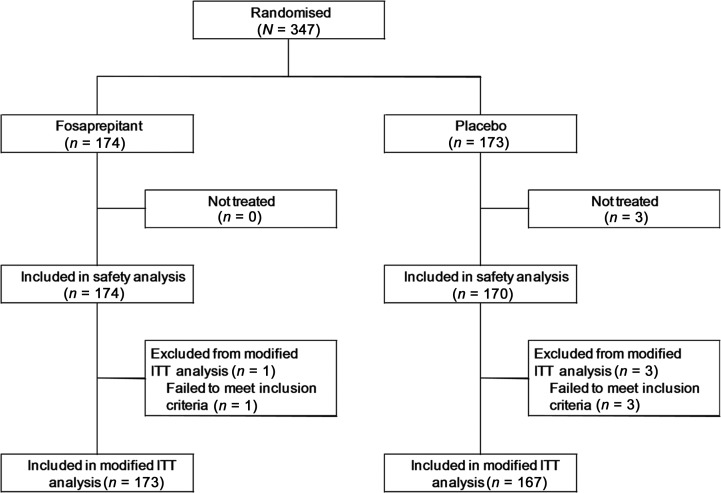

Between August 2009 and December 2009, 347 patients were enrolled in the study, with 173 individuals being randomly assigned to the standard arm and 174 to the fosaprepitant arm (Figure 1). The baseline demographics of the 347 patients are listed in Table 1. None of the demographic parameters differed significantly between the two arms. A total of 71 patients (21%) had received cisplatin before this study. Four patients were subsequently considered to be ineligible and three did not receive the protocol treatment. Therefore, 340 patients (167 in the standard arm and 173 in the fosaprepitant arm) were assessable in the modified ITT analysis, and 344 patients were included in the safety analysis.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of the selection/exclusion and grouping of patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients

| Characteristic | Fosaprepitant (n = 174) |

Placebo (n = 173) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 129 | 74.1 | 128 | 74.0 |

| Female | 45 | 25.9 | 45 | 26.0 |

| Age, years | ||||

| Median | 62.0 | 63.0 | ||

| Range | 26–86 | 25–85 | ||

| ≥65 | 70 | 40.2 | 84 | 48.6 |

| History of motion sickness | 27 | 15.5 | 17 | 9.8 |

| History of vomiting during pregnancya | 17 | 41.5 | 18 | 45.0 |

| Previous treatment with cisplatinb | 36 | 20.7 | 35 | 20.2 |

| Alcohol intake | ||||

| None | 87 | 50.0 | 111 | 64.2 |

| <5/week | 31 | 17.8 | 17 | 9.8 |

| ≥5/week | 56 | 32.2 | 45 | 26.0 |

| Type of malignancyc | ||||

| Respiratory | 123 | 70.7 | 122 | 70.5 |

| Genitourinary | 17 | 9.8 | 16 | 9.2 |

| Digestive | 15 | 8.6 | 16 | 9.2 |

| Head and neck | 13 | 7.5 | 11 | 6.4 |

| Other | 6 | 3.4 | 9 | 5.2 |

| Cisplatin dosed (mg/m2) | ||||

| Mean | 76.2 | 76.2 | ||

| SD | 5.6 | 4.7 | ||

| Median | 76.0 | 75.4 | ||

| Range | 58.0–126.0 | 67.9–103.4 | ||

aOnly female subjects who had conceived a child were included.

bPatients without a history of vomiting (including dry vomiting) were excluded from the patients who had previous treatment with cisplatin.

cNumber of all subjects in each category.

dThere were four patients with missing data in the placebo group.

efficacy

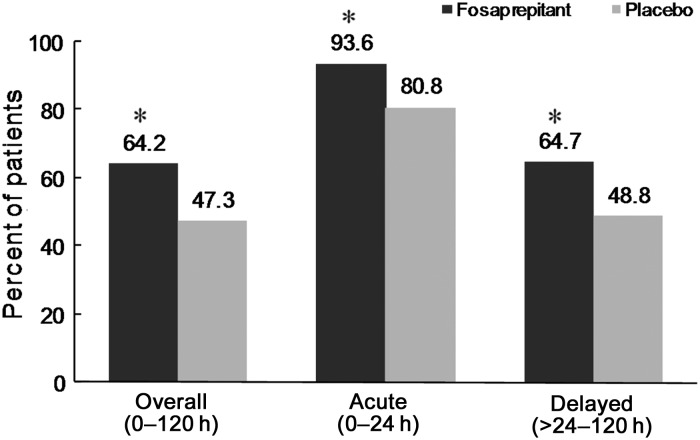

The percentage of patients who achieved a complete response (no emesis and no rescue therapy) in the overall phase (0–120 h) was significantly higher in the fosaprepitant group than in the control group {64% [95% confidence interval (CI) 16–46%] versus 47% [95% CI 10–36%]; P = 0.0015} (Figure 2). Furthermore, in the acute and delayed phases, the percentages of patients with a complete response were significantly higher in the fosaprepitant group than in the control group (acute phase: 94% versus 81%, P = 0.0006; delayed phase: 65% versus 49%, P = 0.0025). Among the patients who had previously been treated with cisplatin and experienced vomiting, the complete response rates in the overall phase were higher in the fosaprepitant group than in the control group (60.0% versus 30.3%).

Figure 2.

Percentages of patients with a complete response (no emesis and no rescue therapy). *P < 0.005 versus placebo group (calculated using the Mantel–Haenszel test after stratification for treatment, sex, presence or absence of at least moderately emetogenic antitumour agent used in combination with cisplatin, and presence or absence of previous treatment with cisplatin). Fosaprepitant group: n = 173; placebo group: n = 167 (overall phase and acute phases), n = 166 (delayed phase).

The results for the other secondary end points are listed in Table 2. The percentages of patients with complete protection (no emesis, no rescue therapy, and no significant nausea) in the overall, acute, and delayed phases, with no emesis in the overall, acute, and delayed phases, and with no rescue therapy in the acute phase were significantly higher in the fosaprepitant group than in the control group. In terms of control of significant nausea and nausea in the overall, acute, and delayed phases, no significant differences were seen. The percentages of patients with no rescue therapy in the overall phase also did not differ significantly.

Table 2.

Percentages of patients reaching other secondary efficacy end points

| Acute phase |

Delayed phase |

Overall phase |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fosaprepitant (n = 173) | Placebo (n = 167) | Fosaprepitant (n = 173) | Placebo (n = 167) | Fosaprepitant (n = 173) | Placebo (n = 167) | |

| Complete protection | 89.6** | 77.2 | 58.4* | 45.8a | 57.8* | 44.3 |

| Total control | 67.6 | 66.5 | 30.1 | 22.9a | 29.5 | 22.2 |

| No emesis | 93.6*** | 80.8 | 68.8*** | 50.6a | 67.6*** | 49.1 |

| No significant nausea | 90.2 | 84.9a | 66.5 | 58.4a | 65.3 | 58.4a |

| No nausea | 67.6 | 67.5a | 30.6 | 24.7a | 30.1 | 24.1a |

| No rescue therapy | 100.0** | 95.8 | 78.6 | 74.3 | 78.6 | 74.3 |

Complete protection: no emesis, no rescue therapy, and no significant nausea (most severe nausea of mild or less severity).

Total control: no emesis, no rescue therapy, and no nausea.

Overall phase: first moderately emetogenic or highly emetogenic antitumour agent (including cisplatin) at 0–120 h after the start of treatment.

Acute phase: first moderately emetogenic or highly emetogenic antitumour agent (including cisplatin) at 0–24 h after the start of treatment.

Delayed phase: first moderately emetogenic or highly emetogenic antitumour agent (including cisplatin) at 24–120 h after the start of treatment.

an = 166.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (calculated by the Mantel–Haenszel test after stratification for treatment, sex, presence or absence of at least moderately emetogenic antitumour agent used in combination with cisplatin, and presence or absence of previous treatment with cisplatin).

Supplementary Figure S1 (available at Annals of Oncology online) shows Kaplan–Meier curves depicting the proportions of patients who did not experience vomiting with respect to time over the entire study period. During the first 12–16 h, the percentages of patients who experienced vomiting were similar between the two groups. However, the fosaprepitant group had significantly more no-vomiting time than the placebo group (P < 0.0001) during the overall phase.

tolerability

All the patients who received the study drug at least once were included in the safety analysis. Table 3 summarises the adverse events reported within 15 days of the start of treatment with the study drug. The overall prevalences of adverse events did not differ significantly between the fosaprepitant group and the control group (99% versus 100%, P = 0.3222). The overall prevalence of drug-related adverse events also did not differ significantly between the fosaprepitant group and the control group (26% versus 28%, P = 0.8005). With respect to the grade distributions of adverse events and drug-related adverse events, no marked differences were observed between the two groups. There were no significant differences between the fosaprepitant group and the control group in the prevalences of serious adverse events (9.2% versus 11%, P = 0.6652) and serious drug-related adverse events (0.6% versus 0.6%, P = 0.9868). There were no treatment-related deaths in either group.

Table 3.

Adverse events (≥20% in the fosaprepitant group)

| Treatment group |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fosaprepitant (n = 174), n (%) |

Placebo (n = 170), n (%) |

|||||||||

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Total | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Total | |

| Leukopenia | 15 (8.6) | 45 (25.9) | 33 (19.0) | 10 (5.7) | 103 (59.2) | 10 (5.9) | 33 (19.4) | 37 (21.8) | 14 (8.2) | 94 (55.3) |

| Reduced appetite | 36 (20.7) | 41 (23.6) | 13 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | 90 (51.7) | 39 (22.9) | 27 (15.9) | 15 (8.8) | 0 (0.0) | 81 (47.6) |

| Neutropenia | 2 (1.1) | 20 (11.5) | 32 (18.4) | 34 (19.5) | 88 (50.6) | 1 (0.6) | 16 (9.4) | 35 (20.6) | 39 (22.9) | 91 (53.5) |

| Nauseaa | 38 (21.8) | 34 (19.5) | 4 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 76 (43.7) | 33 (19.4) | 34 (20.0) | 8 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 75 (44.1) |

| Constipation | 46 (26.4) | 20 (11.5) | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 69 (39.7) | 37 (21.8) | 19 (11.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 56 (32.9) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 31 (17.8) | 15 (8.6) | 8 (4.6) | 4 (2.3) | 58 (33.3) | 25 (14.7) | 14 (8.2) | 18 (10.6) | 5 (2.9) | 62 (36.5) |

| Hiccups | 40 (23.0) | 12 (6.9) | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 55 (31.6) | 30 (17.6) | 27 (15.9) | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 59 (34.7) |

| Malaise | 44 (25.3) | 7 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 51 (29.3) | 40 (23.5) | 4 (2.4) | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 46 (27.1) |

| Anaemiab | 22 (12.6) | 15 (8.6) | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) | 42 (24.1) | 10 (5.9) | 20 (11.8) | 10 (5.9) | 3 (1.8) | 43 (25.3) |

| Increased blood ureab | 32 (18.4) | 7 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 39 (22.4) | 26 (15.3) | 6 (3.5) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 33 (19.4) |

Adverse events reported by the investigator were coded using MedDRA/J Version 12.1. None of the adverse events listed in the table was of grade 5.

aNausea reported outside of the evaluation period for efficacy (0–120 h) was assessed and counted as an adverse event.

bThese events are not listed in the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (v3.0) and were therefore graded as follows: 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe; 4, life-threatening or disabling; and 5, fatal.

Table 4 summarises the infusion-related adverse events, of which the overall prevalence was significantly higher in the fosaprepitant group than in the control group (24% versus 12%, P = 0.0068). In terms of the severity of infusion-related adverse events, severe events were not observed. The prevalence of moderate-grade adverse events was greater in the fosaprepitant group than in the control group (3.4% versus 1.8%, P = 0.3280). The remaining infusion-related adverse events were of only mild severity.

Table 4.

Summary of injection-site reactions

| Percentage of patients with adverse events at the injection site | Treatment group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fosaprepitant (n = 174) |

Placebo (n = 170) |

|||

| n | Percentage | n | Percentage | |

| Overall | 41 | 23.6 | 21 | 12.4 |

| Erythema | 9 | 5.2 | 9 | 5.3 |

| Induration | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Pain | 27 | 15.5 | 11 | 6.5 |

| Swelling | 6 | 3.4 | 5 | 2.9 |

| Phlebitis | 4 | 2.3 | 4 | 2.4 |

| Pruritus | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Reaction | 1 | 0.6 | 2 | 1.2 |

| Extravasation | 3 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Discolouration | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

Adverse events reported by the investigator were coded using MedDRA/J Version 12.1.

In addition to ‘infusion-site pain’, ‘infusion-site erythema’, ‘infusion-site induration’, and ‘thrombophlebitis’ defined in the protocol, adverse events observed at the infusion site and in blood vessels at the infusion site are listed.

Overall, 76 of 174 subjects (44%) in the fosaprepitant group and 62 of 170 subjects (37%) in the control group concomitantly received antitumour agents metabolised by CYP3A4. The prevalences of chemotherapy-related haematological toxicity [febrile neutropenia (fosaprepitant, 1.7%; placebo, 3.5%), neutropenia (fosaprepitant, 51%; placebo, 54%), anaemia (fosaprepitant, 24%; placebo, 25%), and thrombocytopenia (fosaprepitant, 33%; placebo, 37%)] were generally similar between the fosaprepitant and control groups.

discussion

In this randomised phase 3 trial, we have demonstrated the superiority of single-dose fosaprepitant in combination with granisetron and dexamethasone over placebo plus granisetron and dexamethasone for preventing CINV in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin. In previous double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomised phase 3 studies that evaluated aprepitant in combination with ondansetron and dexamethasone, the percentages of patients with a complete response in the overall phase ranged from 63% to 73% [15–17]. The prevalence of a complete response in the present study (64%) was within the range of the previous studies. Casopitant is another NK1 receptor antagonist. A randomised phase 3 study evaluating two schedules of casopitant (single-dose 150-mg regimen and 3-day dose 90-mg/50-mg/50-mg regimen) in combination with ondansetron and dexamethasone for the prevention of CINV reported that the casopitant arms were superior to a combination of ondansetron and dexamethasone alone in preventing nausea and vomiting [18]. Furthermore, administering casopitant on days 2 and 3 did not confer additional efficacy over the single dose of casopitant. On the basis of these two studies, single higher doses of fosaprepitant and casopitant appear to be effective in preventing CINV in patients receiving chemotherapy containing cisplatin. However, casopitant was withdrawn for safety issues. Very recently, Grunberg et al. [10]. conducted a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study to compare intravenous single-dose fosaprepitant with 3-day oral aprepitant, each combined with ondansetron and dexamethasone, for relief from CINV. They demonstrated that a single-dose fosaprepitant 150-mg regimen was non-inferior to a 3-day oral aprepitant (125 mg/80 mg/80 mg) regimen [10]. Single-dose fosaprepitant could be used as an alternative to 3-day aprepitant for the prevention of CINV. Administration of single-dose fosaprepitant may improve adherence and convenience for physicians and patients, resulting in better control of CINV.

In the present phase 3 trial, the complete response rates in the acute and delayed phases were significantly higher in the fosaprepitant group than in the control group (acute phase: 94% versus 81%, P = 0.0006; delayed phase: 65% versus 49%, P = 0.0025). Furthermore, although the prevalence of a complete response was decreased in the delayed phase, the difference in the prevalence of a complete response between the two groups was higher in the delayed phase than in the acute phase (16% versus 13%). This finding suggests that single administration of fosaprepitant (150 mg) is effective for the prevention of emesis in the delayed phase. In addition, in terms of complete protection and no emesis, the fosaprepitant group was statistically superior to the control group.

Currently, control of nausea is more difficult than control of vomiting [19]. In the present study, the two groups did not differ significantly in the control of significant nausea and nausea. Of the three previous randomised phase 3 studies comparing aprepitant plus 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone versus 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy, none found significant differences in the percentages of patients with no significant nausea [15–17]. In terms of control of nausea, the study by Hesketh et al. [15] showed no difference between the arms, while the study by Poli-Bigelli et al. [16] reported superior control for the aprepitant arm. However, a combined analysis of the Hesketh et al. trial and the Poli-Bigelli et al. trial [20] showed a statistically significant difference in nausea and significant nausea. Our results are compatible with a much more modest effect on nausea than vomiting reflected by inconsistent results in the literature.

The major adverse events observed in both arms were mostly related to the chemotherapeutic agents. Fosaprepitant and the equivalent placebo were given intravenously in this study. As expected, the number of infusion-related adverse events was higher in the fosaprepitant group than in the standard arm group. However, these events were mild-to-moderate and clinically manageable. Furthermore, these events did not result in a delay of administration of cancer chemotherapy. Except for injection-site reactions, there were no marked differences in the prevalence and severity of adverse events between the fosaprepitant and placebo groups. Fosaprepitant is a moderate inhibitor of CYP3A4, and drug–drug interactions with several chemotherapeutic agents (including vinca alkaloids, taxanes, and etoposide), which may cause increases in chemotherapy-related haematological toxicity, have been a concern. However, a recent review indicated that aprepitant does not significantly affect the pharmacokinetics of co-administered chemotherapeutic agents that are substrates of CYP3A4 [21]. In the present study, the prevalences of febrile neutropenia, neutropenia, anaemia, and thrombocytopenia in the fosaprepitant group were similar to those in the control group.

In conclusion, fosaprepitant in combination with granisetron and dexamethasone was well-tolerated and more effective than a combination of granisetron and dexamethasone in preventing CINV in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin.

funding

This study was funded by Ono Pharmaceuticals (Osaka, Japan) and has been registered at www.clinicaltrials.jp as JapicCTI-090829.

disclosure

Regarding the work under consideration, HS received honoraria and research funding from Ono Pharmaceuticals; HY received honoraria and research funding from Ono Pharmaceuticals; NK received payment from Ono Pharmaceuticals in relation to consultant or advisory roles, and received honoraria from Ono Pharmaceuticals; MK received payment from Ono Pharmaceuticals in relation to consultant or advisory roles, and received honoraria from Ono Pharmaceuticals; KE received honoraria and research funding from Ono Pharmaceuticals; all other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors thank Tetsu Shinkai, Koichi Goto, and Shinzo Kudo for their contributions to the design and conduct of the clinical study, and all the clinical investigators, patients, nurses, and site staff who participated in the study.

references

- 1.Hesketh PJ. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2482–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basch E, Prestrud AA, Hesketh PJ, et al. Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4189–4198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roila F, Herrstedt J, Aapro M, et al. ESMO/MASCC Guidelines Working Group. Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl. 5):232–243. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology™. Antiemesis V.1. 2012.

- 5.Hale JJ, Mills SG, MacCoss M, et al. Phosphorylated morpholine acetal human neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists as water-soluble prodrugs. J Med Chem. 2000;43:1234–1241. doi: 10.1021/jm990617v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navari RM, Reinhardt RR, Gralla RJ, et al. Reduction of cisplatin-induced emesis by a selective neurokinin-1-receptor antagonist. L-754030 Antiemetic Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:190–195. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901213400304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herrington JD, Jaskiewicz AD, Song J. Randomized, placebo-controlled, pilot study evaluating aprepitant single dose plus palonosetron and dexamethasone for the prevention of acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer. 2008;112:2080–2087. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grunberg SM, Dugan M, Muss H, et al. Effectiveness of a single-day three-drug regimen of dexamethasone, palonosetron, and aprepitant for the prevention of acute and delayed nausea and vomiting caused by moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:589–594. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0535-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lasseter KC, Gambale J, Jin B, et al. Tolerability of fosaprepitant and bioequivalency to aprepitant in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47:834–840. doi: 10.1177/0091270007301800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grunberg S, Chua D, Maru A, et al. Single-dose fosaprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with cisplatin therapy: randomized, double-blind study protocol – EASE. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1495–1501. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.7859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kris MG, Hesketh PJ, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Guideline for Antiemetics in Oncology: Update 2006. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2932–2947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9591. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 5341–5342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCrea JB, Majumdar AK, Goldberg MR, et al. Effects of the neurokinin1 receptor antagonist aprepitant on the pharmacokinetics of dexamethasone and methylprednisolone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:17–24. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marbury TC, Ngo PL, Shadle CR, et al. Pharmacokinetics of oral dexamethasone and midazolam when administered with single-dose intravenous 150 mg fosaprepitant in healthy adult subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51: 1712–1720. doi: 10.1177/0091270010387792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi T, Hoshi E, Takagi M, et al. Multicenter, phase II, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized study of aprepitant in Japanese patients receiving high-dose cisplatin. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:2455–2461. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hesketh PJ, Grunberg SM, Gralla RJ, et al. The oral neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin – the Aprepitant Protocol 052 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4112–4119. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poli-Bigelli S, Rodrigues-Pereira J, Carides AD, et al. Addition of the neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist aprepitant to standard antiemetic therapy improves control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Latin America. Cancer. 2003;97:3090–3098. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmoll HJ, Aapro MS, Poli-Bigelli S, et al. Comparison of an aprepitant regimen with a multiple-day ondansetron regimen, both with dexamethasone, for antiemetic efficacy in high-dose cisplatin treatment. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1000–1006. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grunberg SM, Rolski J, Strausz J, et al. Efficacy and safety of casopitant mesylate, a neurokinin 1 (NK1)-receptor antagonist, in prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving cisplatin-based highly emetogenic chemotherapy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:549–558. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grunberg SM, Deuson RR, Mavros P, et al. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis after modern antiemetics. Cancer. 2004;100:2261–2268. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warr DG, Grunberg SM, Gralla RJ, et al. The oral NK1 antagonist aprepitant for the prevention of acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: pooled data from 2 randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trials. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1278–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aapro MS, Walko CM. Aprepitant: drug-drug interactions in perspective. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2316–2323. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.