Abstract

Background

Temozolomide (TMZ) is widely used for chemotherapy of metastatic melanoma. We hypothesized that epigenetic modulators will reverse chemotherapy resistance, and in this article, we report studies that sought to determine the recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D), safety, and efficacy of decitabine (DAC) combined with TMZ.

Patients and methods

In phase I, DAC was given at two dose levels: 0.075 and 0.15 mg/kg intravenously daily × 5 days/week for 2 weeks, TMZ orally 75 mg/m2 qd for weeks 2–5 of a 6-week cycle. The phase II portion used a two-stage Simon design with a primary end point of objective response rate (ORR).

Results

The RP2D is DAC 0.15 mg/kg and TMZ 75 mg/m2. The phase II portion enrolled 35 patients, 88% had M1c disease; 42% had history of brain metastases. The best responses were 2 complete response (CR), 4 partial response (PR), 14 stable disease (SD), and 13 progressive disease (PD); 18% ORR and 61% clinical benefit rate (CR + PR + SD). The median overall survival (OS) was 12.4 months; the 1-year OS rate was 56%. Grade 3/4 neutropenia was common but lasted >7 days in six patients.

Conclusions

The combination of DAC and TMZ is safe, leads to 18% ORR and 12.4-month median OS, suggesting possible superiority over the historical 1-year OS rate, and warrants further evaluation in a randomized setting.

Keywords: decitabine, melanoma, pharmacokinetic analysis, temozolomide

introduction

Melanoma incidence is rapidly increasing throughout the world. Based on the American Cancer Society estimates, in 2012 there were ∼76 250 new cases of invasive melanoma in the United States resulting in 9180 deaths [1, 2]. The prognosis for patients with metastatic disease remains poor, with a 5-year survival rate of 6% and median overall survival (OS) of ∼6–8 months [3]. The anti-CTLA4 antibody, ipilimumab, was the first agent to improve survival of metastatic melanoma, with the median survival of 10.9 months and the 1-year OS rate of 48%; the objective response rate (ORR) was only 10.9%, as was the increment in survival at 2 years [4, 5]. Small-molecule inhibitors of mutation-activated BRAF have achieved unprecedented response rates exceeding 50% with improved survival as well. However, this benefit is limited to patients whose tumors harbor the BRAFV600E mutation (40%–50% of patients) and is not associated with durable responses (median duration ∼6 months) [6, 7].

Therefore, alkylating agents remain an important therapeutic option particularly relevant for metastatic melanoma with wild-type BRAF and for disease that has progressed on ipilimumab and/or BRAF-directed therapy. Dacarbazine (DTIC) is the only Food and Drug Administration-approved chemotherapeutic agent in current use for the treatment of metastatic melanoma, despite response rates of ∼10% in phase III trials [8–10]. Temozolomide (TMZ) is spontaneously converted to the same active metabolite 3-methyl-(triazen-1-yl)imidazole-4-carboxamide after oral administration and has shown clinical activity at least equivalent to DTIC against melanoma [8].

The O6-methylguanine (O6-MeG) base lesion is responsible for the cytotoxicity of TMZ and directly repaired by the DNA repair protein O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT), leading to cell survival and clinical drug resistance [11]. However, the cytotoxicity of the O6-MeG lesion results only when a functional DNA mismatch repair (MMR) pathway exists to recognize the damage and initiate cell death. MMR deficiency is often induced by epigenetic silencing of key MMR genes, such as MLH1, through hypermethylation of its promoter region and can be reversed with hypomethylating agents [e.g. decitabine (DAC)] [12]. DAC has been utilized as a cytotoxic agent at high doses but ample evidence indicates that doses that are 30-fold lower can exert epigenetic effects in human studies, which is more amenable to combination therapy [13, 14]. We have observed a significant inverse association between MLH1 promoter methylation and clinical antitumor response and OS in a retrospective study including 66 melanoma patients at our institution (unpublished data) [15]. We, therefore, hypothesized that the combination of TMZ and DAC will effect dual modulation of DNA repair through the depletion of MGMT and re-expression of MMR proteins, resulting in improved clinical response. In this article, we report the results of a phase I/II clinical trial of the combination of DAC and extended-schedule TMZ to reverse melanoma resistance to TMZ. To our knowledge, this is the first reported approach to dual DNA repair modulation in the clinic.

patients and methods

study design

The study was a non-randomized open-label phase I/II clinical trial conducted at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI 07–008, NCT00715793 on clinicaltrials.gov) supported by Eisai, Inc. and Schering Plough Research Institute (now Merck, Inc.). Analysis was supported by the Melanoma Program of the UPCI, and a Developmental Project to HT from the Skin Specialized Program in Research Excellence (SPORE) in skin cancer. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board and all patients signed informed consent. The investigators designed, conducted, and analyzed the study independently. Toxicity assessments used CTCAE v3.0 and efficacy assessments with a computed tomography scan carried out every 12 weeks, using RECIST v1.0.

patients

The eligible patients had non-resectable stage IIIB/C or stage IV metastatic melanoma; either no prior therapy or have progressed despite prior therapies. Prior biological therapy was allowed, and one line of prior chemotherapy was allowed if it did not include TMZ or DTIC. Patients had to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) ≤2, adequate bone marrow, renal, and hepatic function. Patients with treated brain metastases were allowed if stable for >4 weeks or >2 weeks if treated with stereotactic radiosurgery.

chemotherapy regimen

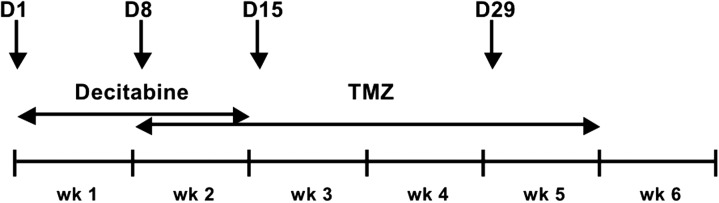

DAC was administered at the specified dose level, intravenously over 30 min, daily for 5 days a week for the first 2 weeks of a 6-week cycle. TMZ was administered orally at 75 mg/m2 daily for 4 weeks (weeks 2–5) of a 6-week cycle (Figure 1). The dose of TMZ was fixed throughout the phase I and phase II portions of the study. In the phase I portion, only two dose levels of DAC were used: 0.075 mg/kg at dose level 1 (DL1) and 0.15 mg/kg at dose level 2 (DL2).

Figure 1.

Treatment administration schedule: decitabine (DAC) is given intravenously at the specified dose level 5 days/week for the first 2 weeks; Temozolomide is given orally at 75 mg/m2 daily starting on day 8 for a total of 4 weeks; week 6 is a rest week. The arrows depict the days on which pharmacokinetic studies were carried out (days 1 and 8) and on which peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) and optional serial tumor biopsies were collected for pharmacodynamic analyses (days 1, 8, 15, and 29).

statistical considerations

Two dose levels were explored in the phase I portion of the study. A modified 3 + 3 ‘up and down’ design was used. Given the knowledge that DAC exhibits its epigenetic effects at 30-fold lower doses than at its maximum-tolerated dose (MTD), we did not intend to escalate DAC to the MTD, but to utilize a dose of 0.15 mg/kg, if determined to be safe, as the recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D) [13, 14]. Patients were considered assessable for toxicity if they received one complete cycle of therapy, or if they did not complete the cycle secondary to toxic effects. Non-assessable patients were replaced. Dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) were defined as grade 4 neutropenia or thrombocytopenia which lasts >7 days; grade 3 or 4 febrile neutropenia; grade 3 or greater non-hematological toxic effects.

A Simon two-stage design was used to evaluate the efficacy of the treatment at RP2D. A response rate of ≥21% was considered worthy of further testing, while a response rate of ≤7% was not. In the first stage, if at least 1 of 14 patients responded, an additional 20 patients would be recruited. A total of five or more responses (out of 34 assessable patients) would lead to the conclusion that the treatment is worth further study. The type I and type II errors were 10% and 15%, respectively. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the OS and the progression-free survival (PFS). PFS was defined as the time from study entry until the documented radiological or symptomatic progression; OS was defined as the time from study entry until the death or date of last contract. To compare the OS and PFS of the patients in the current trial with historical controls, adjusting for important clinical prognostic factors, we used the tables provided by Korn et al. [16] and estimated the expected benchmark 1-year OS and 6-month PFS rates based on the patients' gender, visceral disease status, and brain metastasis status. The observed 1-year OS and 6-month PFS rates were compared with the expected estimates by a one-sided exact binomial test. All statistical analyses were carried out using R (version 2.11.1, http://www.R-project.org).

pharmacokinetic sampling

Samples for pharmacokinetic (PK) analyses were obtained on the first 14 patients. On days 1 and 8, blood samples were collected at 0, 15, and 30 min (just before the end of DAC infusion); and 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 min, 2, 4, 6, and 23 h after the end of DAC infusion. PK analyses were carried out for both DAC and TMZ (please refer to the supplementary data for details, available at Annals of Oncology online).

pharmacodynamic sampling

Pharmacodynamic sampling was carried out on all accrued patients. During cycle 1 on days 1, 8, 15, and 29, whole blood was collected and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated, core tumor biopsies were optional and obtained from six consenting patients with accessible, evaluable disease (please refer to the supplementary data for details, available at Annals of Oncology online).

results

A total of 39 patients were enrolled in the study between July 2008 and September 2010. The phase I part of the study enrolled three patients to DL1; however, one patient did not complete cycle 1 secondary to disease progression and was replaced. No DLTs were observed and dose escalation proceeded to DL2. Six patients were enrolled on DL2 and no DLTs were observed. DL2 was, therefore, declared the RP2D and enrollment to the phase II part started. The six patients treated on DL2 were analyzed with the phase II population. A total of 35 patients were enrolled in the phase II part, of which two were not assessable for tumor response (Table 1). The median number of cycles administered was two, with 20% of patients receiving more than four cycles; the total number of administered cycles was 101. All patients were off-study at the time of data cut-off on 31 December 2011.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| N | Median (range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 39 | 63.3 (36.2–77.4) |

| N | (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 12 | 31 |

| Male | 27 | 69 |

| Stage | ||

| Stage IIIC | 2 | 5 |

| Stage IV-M1a | 4 | 10 |

| Stage IV-M1c | 33 | 85 |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) | ||

| 0 | 10 | 26 |

| 1 | 28 | 71 |

| 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Any prior treatment | ||

| Chemotherapy | 9 | 23 |

| Immunotherapy | 20 | 51 |

| CNS metastases | ||

| Present | 16 | 42 |

| Absent | 23 | 58 |

toxicity

Hematologic toxic effects were common representing most grade 3/4 toxic effects observed. Neutropenia occurred typically at weeks 4 to 5 and the patients recovered in 1–2 weeks. Neutropenic fever occurred in only two instances which was managed successfully with antibiotics and growth factor support. Grade 3/4 neutropenia lasted for more than 7 days in 6 out of 34 patients assessable for toxicity on DL2 for an overall DLT rate of 18%. Dose modifications allowed patients to continue treatment and only two patients ultimately discontinued therapy secondary to toxicity. Growth factor support was only used in patients with neutropenic fever. Common non-hematologic toxic effects were grade 1/2 fatigue (59%) and grade 1 nausea (54%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Grade 2 or higher adverse events and number of patients by worst grade (all cycles)

| Category | Type of adverse event | Grade |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Totala | ||

| Blood/bone marrow | Hemoglobin | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Leukocytes (total WBC) | 8 | 16 | 7 | 0 | 31 | |

| Lymphopenia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Neutrophils/granulocytes | 4 | 9 | 19 | 0 | 32 | |

| Platelets | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| Cardiac general | Hypertension | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Constitutional symptoms | Fatigue (asthenia, lethargy, malaise) | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Fever (in the absence of neutropenia) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Weight loss | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Dermatology/skin | Pruritus/itching | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Rash/desquamation | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Gastrointestinal | Anorexia | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Constipation | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| Diarrhea | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Ileus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mucositis/stomatitis (clinical exam), oral cavity | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Nausea | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| Vomiting | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Infection/febrile neutropenia | Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Infection with normal ANC, skin (cellulitis) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Metabolic/laboratory | Hypoalbuminemia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Creatinine | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Metabolic/laboratory: other | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| hypophosphatemia | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| Neurology | Ataxia (incoordination) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Dizziness | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Neurology:- other (specify, __) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Neuropathy: motor | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Neuropathy: sensory | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Pain | Pain, abdomen NOS | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Pain, back | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Pain, head/headache | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Pulmonary/upper respiratory | Cough | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Vascular | Thrombosis/thrombus/embolism | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

aEach patient is counted at most once within each type of adverse event.

NOS, not otherwise specified.

efficacy

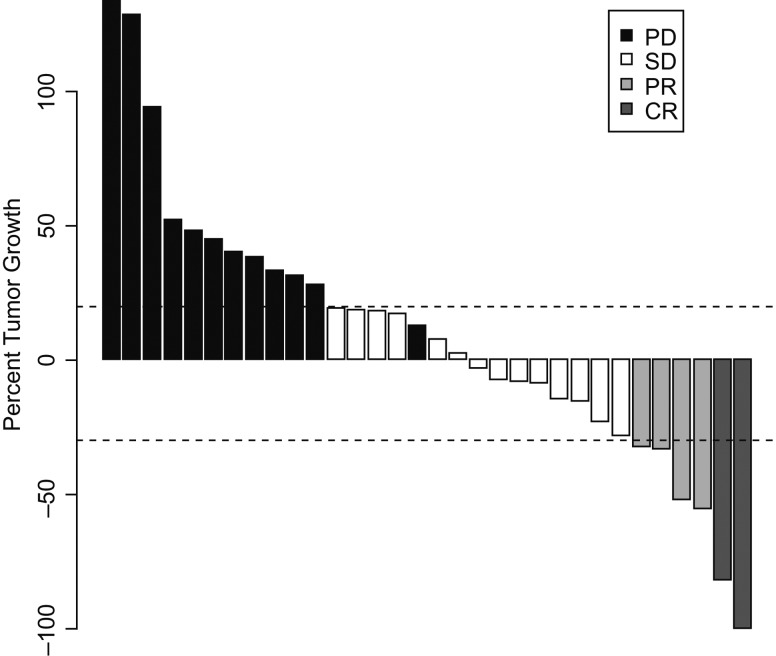

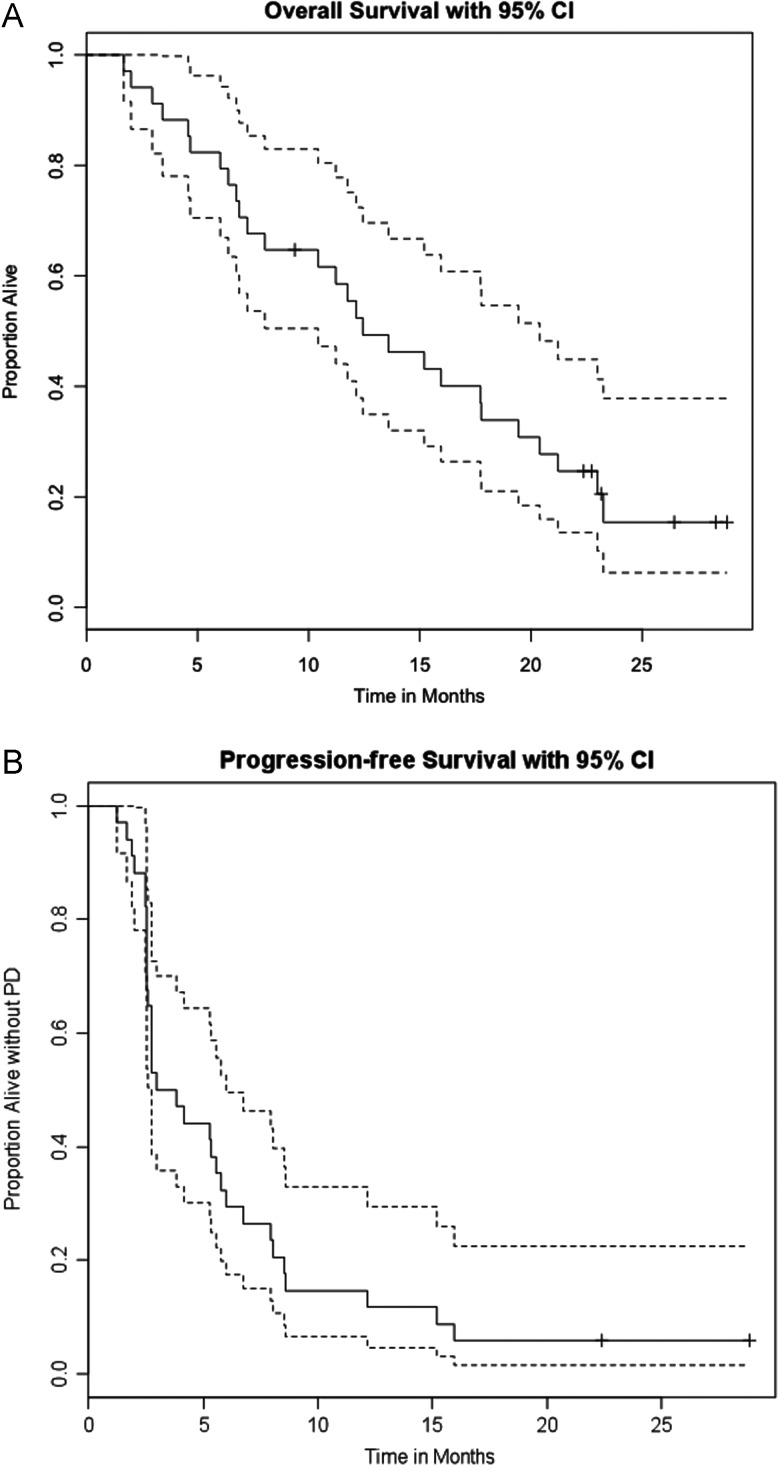

Thirty-three patients were assessable for response on the phase II portion. Of those, two patients had complete responses (CR), four had confirmed partial responses (PR), 14 had stable disease (SD), and 13 had progressive disease (PD). The ORR was 18%. The disease control rate (DCR) comprised of CR + PR + SD was 61% (Figure 2). The median PFS was 3.4 months, and the 6-months PFS rate was 32% [95% CI 20% to 53%] (Figure 3B). The median OS was 12.4 months [95% CI 10.4–20.4 months]. The 1-year OS rate was 56% [95% CI 41% to 75%] (Figure 3a). Eighteen (18) out of the remaining 33 patients survived beyond 1 year, which is significantly higher than the estimated 1-year OS rate of 16.6% for these patients (P < 0.0001, Table 2). Twenty-three (23) out of the 34 patients either progressed or died by 6 months, making the 6-months PFS rate 32.4%, which is significantly higher than the predicted historical 6-month PFS rate of 14% (P = 0.004, Table 2). The mutational status was only available for 13 patients, and of these only 4 had BRAFV600E mutation and there was no association with clinical response or survival.

Figure 2.

Waterfall plot: best response by RECIST 1.0 is depicted as percent change on the y-axis. Every bar represents one patient. The horizontal dotted lines represent the RECIST limits for progression (+20%) or objective response (−30%). Complete response (CR) is represented in dark grey, partial response (PR) in grey, stable disease (SD) in white, and progressive disease (PD) in black. Note that one patient who had SD by RECIST was considered PD (black) as there was evidence of new CNS metastases on evaluation.

Figure 3.

(A) Overall survival with 95% CI. (B) Progression-free survival (PFS) with 95% CI.

pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses

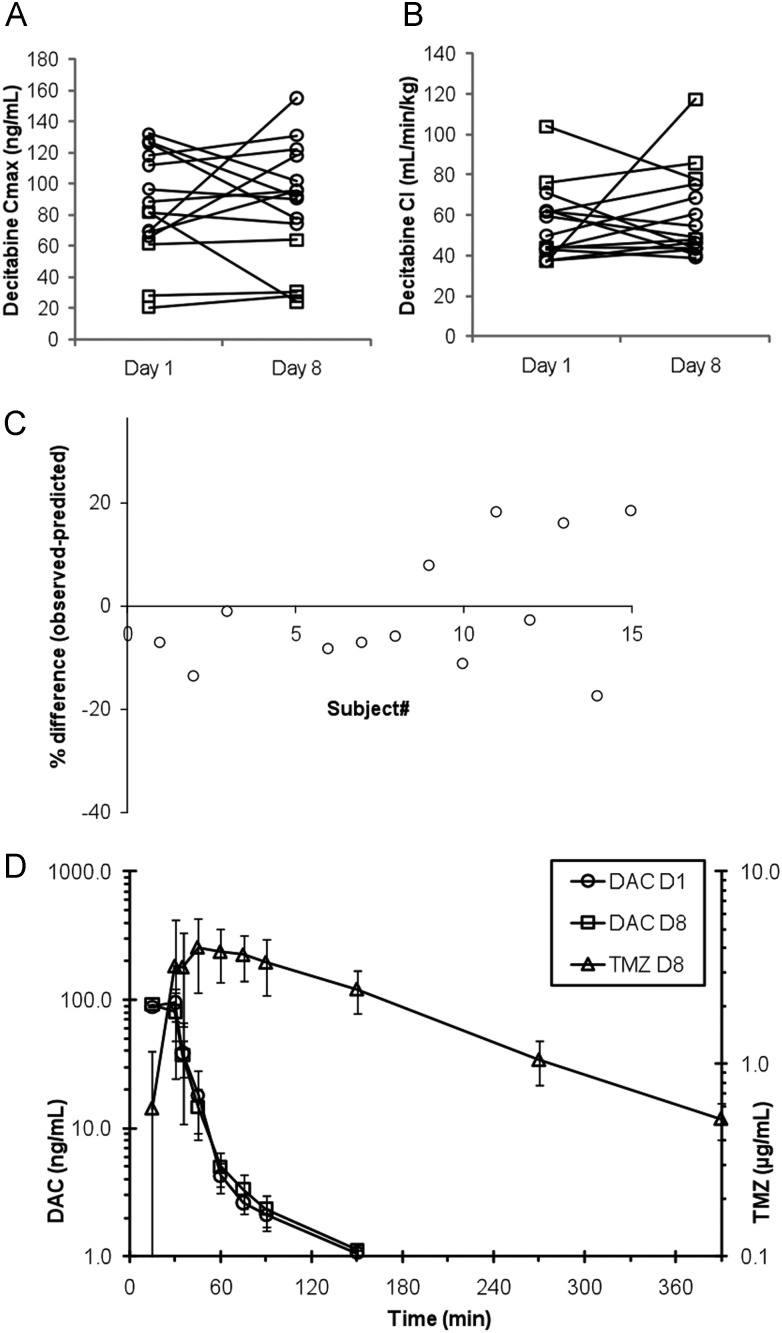

Pharmacokinetic data were available for DAC in 15 patients and for TMZ in 14 patients. We did not observe statistically significant changes in DAC pharmacokinetic parameters between day 1 and day 8 (Figures 4A and B, and supplementary Table 3S, available at Annals of Oncology online). Likewise, we did not observe statistically significant differences between observed apparent clearance and predicted apparent clearance for TMZ (Figure 4C, and supplementary Table 2S, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 4.

(A) Intra-individual changes in decitabine (DAC) Cmax between day 1 (DAC alone) and day 8 (DAC with temozolomide); dose level 1 (squares) and dose level 2 (circles); P = 0.847. (B) Intra-individual changes in DAC clearance between day 1 and (DAC alone) and day 8 (DAC with temozolomide); dose level 1 (squares) and dose level 2 (circles); P = 0.639. (C) Difference between predicted and observed temozolomide plasma exposure (AUC0-inf). The average difference was 1.6%, P = 0.855. (D) Concentration versus time profile based on the average (±SD) concentration data of 14 patients receiving 75 mg/m2 temozolomide (TMZ) PO with DAC.

In six patients, tumor tissues and PBMCs were available from pre- and post-treatment (supplementary Table 5S, available at Annals of Oncology online). We investigated the changes in promoter methylation and gene expression of all DNA repair genes including MGMT and MMR genes but did not identify significant changes. Interestingly, DAC seemed to induce hypomethylation of p16 and HgF promoter regions associated with increased gene expression in five of six cases (83%). Both the genes have been implicated in response to DAC in patients with MDS, AML, and sickle cell disease [17–19].

discussion

In this phase I/II study, we have determined that DAC can be safely added to extended-schedule TMZ and leads to improvement in response rates as well as progression-free and OS rates for patients with metastatic melanoma.

Alkylating agents continue to have a role in the treatment of metastatic melanoma, limited chiefly by the development of chemotherapy resistance. Modulation of DNA repair mechanisms has the potential to reverse chemotherapy resistance and improve the efficacy of alkylators [20].

The MGMT levels are associated with alkylator resistance and the MGMT promoter methylation status has served as a predictor of response to alkylator-based therapy in glioblastoma multiforme. Unlike other DNA repair mechanisms, MGMT does not activate a pathway, but is a single protein that recognizes and repairs DNA damage through its specificity for O6- substituted purines [21]. O6-MeG analogs were developed with the goal of depleting MGMT by presenting it with decoy base lesions that are themselves devoid of toxicity. However, extensive experience with IV O6-benzyl guanine (O6-BeG) and the oral O6-(4-bromothenyl)-guanine (lomeguatrib) confirmed that O6-MeG analogs lead to increased myelosuppression that is not paralleled by an increase in the efficacy of chemotherapy in several malignancies including melanoma [22–31].

A low-dose extended-schedule administration of TMZ offers more sustained MGMT inhibition, while the total delivered dose of the alkylating agent exceeds the standard 5-day regimen [32]. In a large EORTC randomized phase III trial, TMZ given on a ‘week on-week off’ schedule showed a minor increase in response rates (10% versus 14%, P = 0.05), although it did not impart any survival benefit over DTIC [33].

The lack of clinical efficacy observed with the single-pathway inhibition of MGMT could be, in part, due to the dependence of this pathway on a functional MMR system for cytotoxicity to occur [15]. MGMT provides an efficient mechanism of repair for O6-MeG, while MMR transforms it into a lethal lesion by initiating apoptosis. In the absence of MMR, O6-MeG persists without leading to apoptosis and the affected cell survives. MMR deficiency occurs primarily through epigenetic silencing of the key MMR genes by promoter methylation, which can be reversed using epigenetic modulators such as DAC [34]. We have identified the promoter methylation of MLH1 to be strongly associated with decreased clinical response and survival in a retrospective cohort of melanoma patients (unpublished data) [15]. Treatment with DAC has been reported to lead to re-expression of MLH1 resulting in a proficient MMR system and sensitizing cancer cells to the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy [13, 35].

DAC induces hypomethylation in tumor xenografts associated with increased sensitivity to carboplatin [35]. A phase I clinical trial of DAC in combination with carboplatin (Bristol Myers Squibb, New York, NY) determined the MTD to be DAC IV at 90 mg/m2 (day 1) followed by carboplatin IV at area under the curve 6 (AUC 6, day 8) every 28 days. DAC produced a reduction in DNA methylation similar to that observed in the xenograft model [36]. For an individual with an average body surface area of ∼1.7 m2 and 75 kg in weight, this would amount to 0.2 mg/kg given daily IV for 10 days. This is roughly equivalent to the dose used in our study. Also, the dose and schedule of DAC we used are comparable with a dosage of 13 mg/m2 as administered on the standard MDS schedule (20 mg/m2 given for 5 days) and to the dose tested in a phase I trial combined with high-dose interleukin-2 that led to significant hypomethylation in patients with metastatic melanoma [14, 37]. In the current study, DAC at 0.15 mg/kg was well tolerated and led to the expected incidence of grade 4 neutropenia. Neutropenia lasted >7 days in only 18% of patients, and was associated with neutropenic fever in two patients. In general, neutropenia was asymptomatic and reversible without the use of growth factors. Full doses of TMZ were administered, dose modifications were infrequent, and allowed most patients to complete therapy safely.

The combination of DAC and TMZ was associated with improved antitumor efficacy and the trial reached the pre-specified primary end point for efficacy based on an OR rate of 18% [90% CI 8% to 33%]. The median PFS was 3.4 months and the 6-month PFS rate of 32% was also modestly improved over that of TMZ in the standard schedule (Middleton et al. [8],18%, P < 0.0001) and in an extended schedule (EORTC [33], 21% P < 0.0001). Most promising was the improvement we observed in OS here. Specifically, the observed median OS in the current study was 12.4 months and was significantly higher than 7.9 months in the Middleton study (one sample log-rank test, P value = 0.003), and 9.2 months observed in the more contemporary EORTC trial (P = 0.02). This OS benefit is unlikely to be due to post-protocol therapy, since only two patients in this cohort ever received ipilimumab after completing 9 months of TMZ in the present study and none received vemurafenib. In order to account for this, we examined the 1-year OS rate: this was significantly higher at 54.5% compared with the landmark of 25% derived from the Korn meta-analysis of prior phase II trials [16].

Patient selection in a non-randomized phase II trial limits the extrapolation of results; however, our patient population exhibited multiple features expected to result in poorer outcomes. For instance, both the UK and EORTC trials excluded patients with CNS metastases; yet 42% of the phase II patients in this study had prior CNS metastases. In the Korn meta-analysis, visceral disease (M1c) and compromised ECOG PS >0 have been established as adverse prognostic factors. Visceral disease was present in 88% of our patients and 70% had PS = 1. A reconstructed historical control survival analysis based on the Korn data showed an expected 1-year OS rate of only 16% for our patient population, with significant improvement in OS observed in our study (two-sided P value = 0.003, Table 2). This may be an underestimation for patients with brain metastases treated with modern stereotactic radiation approaches, but is still substantially lower than the survival observed in our study [38].

We have considered the theoretical consideration that DAC may potentially lead to hypomethylation of the MGMT promoter, increased MGMT levels, and ultimately affect the chemotherapy outcomes adversely. However, MGMT protein levels have been shown to be suppressed by >70% with only 2 weeks of low-dose daily TMZ, and therefore 4 weeks of continuous administration would make the contribution of any potential MGMT expression induced by DAC rather negligible. It should be noted that low MGMT levels have been reported to manifest clinically as neutropenia, while higher MGMT levels are likely to be protective from myelosuppression. While MGMT levels were not assessed in our study, they are unlikely to have been elevated given the observed neutropenia and the greatly improved clinical outcome.

The TMZ plasma exposures observed in this study concord with the literature [39]. The observed volumes of distribution differed from those predicted, and the half-life calculated from the clearance and volume of distribution was altered from the expected. However, the differences were small, and do not affect the total exposure and the observed statistical difference is, therefore, not considered relevant. The clearance and distribution volumes for DAC observed in this study were also similar to the values reported in the literature [40]. Based on the PK analysis, there is no indication that DAC increased exposure to TMZ and therefore, this benefit cannot be ascribed to higher alkylator effect.

Our hypothesis that the improvement in TMZ efficacy is mediated by an effect upon DNA repair genes was not substantiated by the PD data with the caveat that the sample size for PD analysis was limited. This limits our ability to conclude that the combination exerted this favorable effect through dual DNA repair modulation, as we hypothesized. Other mechanisms can also be involved including immune-mediated mechanisms as the patterns of response and clinical benefit are reminiscent of immune therapy with ipilimumab. There is emerging evidence that chemotherapy with agents such as TMZ may improve chemokine expression and increase lymphocyte infiltration into tumors [41]. DAC has been recognized for its ability to re-express cancer testis antigens (CTA) and the combination may have synergized at that level [42].

conclusion

We have conducted a phase I/II clinical trial with DAC combined with extended-schedule TMZ for patients with metastatic melanoma. This is, to our knowledge, the first reported dual DNA repair inhibition that has been reported in the clinic. A recommended phase II dose in combination has been associated with improved clinical outcomes: response rate, clinical benefit rate, median PFS, and median OS were all improved. The results of this trial warrant further exploration and confirmation in a randomized multicenter setting.

funding

The clinical study was jointly supported by Merck, Inc. and Eisai, Inc.; analysis was supported by the Developmental Research Project to HT from the Skin Specialized Program in Research Excellence (SPORE) P50-CA121973 and both HT and JHB through P30-CA47904 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Nancy Davidson, Robert Branch, Roger Day, and Mark Unruh, all at the University of Pittsburgh, for their input and support; as well as the Merrill Egorin Writing Group at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute for their help with the manuscript.

references

- 1.American Cancer Society. 2012. http://www.cancer.org/

- 2.Jemal A, Saraiya M, Patel P, et al. Recent trends in cutaneous melanoma incidence and death rates in the United States, 1992–2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:S17–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.032. e11–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barth A, Wanek LA, Morton DL. Prognostic factors in 1521 melanoma patients with distant metastases. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809–819. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Middleton MR, Grob JJ, Aaronson N, et al. Randomized phase III study of temozolomide versus dacarbazine in the treatment of patients with advanced metastatic malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:158–166. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bedikian AY, Millward M, Pehamberger H, et al. Bcl-2 antisense (oblimersen sodium) plus dacarbazine in patients with advanced melanoma: the Oblimersen Melanoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4738–4745. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schadendorf D, Ugurel S, Schuler-Thurner B, et al. Dacarbazine (DTIC) versus vaccination with autologous peptide-pulsed dendritic cells (DC) in first-line treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: a randomized phase III trial of the DC study group of the DeCOG. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:563–570. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu L, Gerson SL. Targeted modulation of MGMT: clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:328–331. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barvaux VA, Ranson M, Brown R, et al. Dual repair modulation reverses temozolomide resistance in vitro. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Issa JP, Garcia-Manero G, Giles FJ, et al. Phase 1 study of low-dose prolonged exposure schedules of the hypomethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine) in hematopoietic malignancies. Blood. 2004;103:1635–1640. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gollob JA, Sciambi CJ, Peterson BL, et al. Phase I trial of sequential low-dose 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine plus high-dose intravenous bolus interleukin-2 in patients with melanoma or renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4619–4627. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobol RW, Tawbi H, Jukic D, et al. Mismatch repair (MMR) and base excision repair (BER) protein expression correlates with clinical response to dacarbazine (DTIC)/temozolomide (TMZ) therapy of patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:8015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korn EL, Liu PY, Lee SJ, et al. Meta-analysis of phase II cooperative group trials in metastatic stage IV melanoma to determine progression-free and overall survival benchmarks for future phase II trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:527–534. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart DJ, Issa JP, Kurzrock R, et al. Decitabine effect on tumor global DNA methylation and other parameters in a phase I trial in refractory solid tumors and lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3881–3888. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schrump DS, Fischette MR, Nguyen DM, et al. Phase I study of decitabine-mediated gene expression in patients with cancers involving the lungs, esophagus, or pleura. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5777–5785. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koshy M, Dorn L, Bressler L, et al. 2-deoxy 5-azacytidine and fetal hemoglobin induction in sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2000;96:2379–2384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tawbi HA, Buch SC. Chemotherapy resistance abrogation in metastatic melanoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2010;8:259–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerson SL. MGMT: its role in cancer aetiology and cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:296–307. doi: 10.1038/nrc1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson AJ, Middleton MR, McGown G, et al. O(6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase depletion and DNA damage in patients with melanoma treated with temozolomide alone or with lomeguatrib. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1250–1256. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tawbi HA, Villaruz L, Tarhini A, et al. Inhibition of DNA repair with MGMT pseudosubstrates: phase I study of lomeguatrib in combination with dacarbazine in patients with advanced melanoma and other solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:773–777. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kefford RF, Thomas NP, Corrie PG, et al. A phase I study of extended dosing with lomeguatrib with temozolomide in patients with advanced melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1245–1249. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gajewski TF, Sosman J, Gerson SL, et al. Phase II trial of the O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase inhibitor O6-benzylguanine and 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea in advanced melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7861–7865. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spiro TP, Gerson SL, Liu L, et al. O6-benzylguanine: a clinical trial establishing the biochemical modulatory dose in tumor tissue for alkyltransferase-directed DNA repair. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2402–2410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schilsky RL, Dolan ME, Bertucci D, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacological study of O6-benzylguanine followed by carmustine in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3025–3031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quinn JA, Desjardins A, Weingart J, et al. Phase I trial of temozolomide plus O6-benzylguanine for patients with recurrent or progressive malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7178–7187. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinn JA, Jiang SX, Reardon DA, et al. Phase II trial of temozolomide plus o6-benzylguanine in adults with recurrent, temozolomide-resistant malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1262–1267. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan CW, Dolan ME, Brockstein BB, et al. A phase II trial of O6-benzylguanine and carmustine in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;58:634–639. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ranson M, Hersey P, Thompson D, et al. Randomized trial of the combination of lomeguatrib and temozolomide compared with temozolomide alone in chemotherapy naive patients with metastatic cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2540–2545. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tolcher AW, Gerson SL, Denis L, et al. Marked inactivation of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase activity with protracted temozolomide schedules. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:1004–1011. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel PM, Suciu S, Mortier L, et al. Extended schedule, escalated dose temozolomide versus dacarbazine in stage IV melanoma: final results of a randomised phase III study (EORTC 18032) Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1476–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Decitabine (Dacogen) for myelodysplastic syndromes. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2006;48:91–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plumb JA, Strathdee G, Sludden J, et al. Reversal of drug resistance in human tumor xenografts by 2′-deoxy-5-azacytidine-induced demethylation of the hMLH1 gene promoter. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6039–6044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Appleton K, Mackay HJ, Judson I, et al. Phase I and pharmacodynamic trial of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor decitabine and carboplatin in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4603–4609. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kantarjian H, Oki Y, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Results of a randomized study of 3 schedules of low-dose decitabine in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:52–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liew DN, Kano H, Kondziolka D, et al. Outcome predictors of gamma knife surgery for melanoma brain metastases. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:769–779. doi: 10.3171/2010.5.JNS1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostermann S, Csajka C, Buclin T, et al. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid population pharmacokinetics of temozolomide in malignant glioma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3728–3736. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cashen AF, Shah AK, Todt L, et al. Pharmacokinetics of decitabine administered as a 3-h infusion to patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:759–766. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0531-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hong M, Puaux AL, Huang C, et al. Chemotherapy induces intratumoral expression of chemokines in cutaneous melanoma, favoring T-cell infiltration and tumor control. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6997–7009. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fratta E, Sigalotti L, Colizzi F, et al. Epigenetically regulated clonal heritability of CTA expression profiles in human melanoma. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:352–358. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.