Abstract

Following thymic output, αβ+CD4+ T cells become activated in the periphery when they encounter peptide–major histocompatibility complex. A combination of cytokine and co-stimulatory signals instructs the differentiation of T cells into various lineages and subsequent expansion and contraction during an appropriate and protective immune response. Our understanding of the events leading to T-cell lineage commitment has been dominated by a single fate model describing the commitment of T cells to one of several helper (TH), follicular helper (TFH) or regulatory (TREG) phenotypes. Although a single lineage-committed and dedicated T cell may best execute a single function, the view of a single fate for T cells has recently been challenged. A relatively new paradigm in αβ+CD4+ T-cell biology indicates that T cells are much more flexible than previously appreciated, with the ability to change between helper phenotypes, between helper and follicular helper, or, most extremely, between helper and regulatory functions. In this review, we comprehensively summarize the recent literature identifying when TH or TREG cell plasticity occurs, provide potential mechanisms of plasticity and ask if T-cell plasticity is beneficial or detrimental to immunity.

Keywords: T helper cell, T regulatory cell, infection

2. Introduction: T-cell differentiation programmes

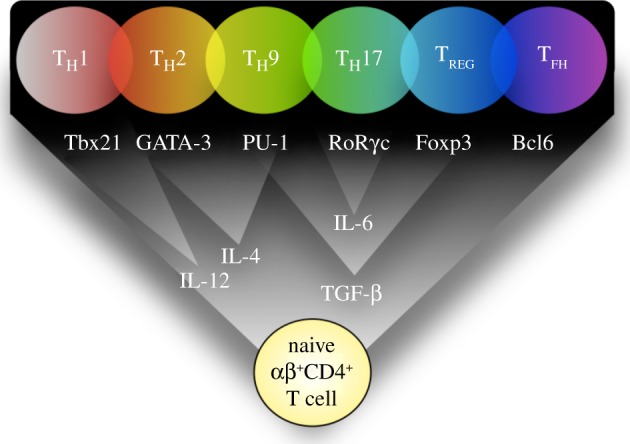

The differentiation of αβ+CD4+ T cells is the result of combined T-cell receptor (TCR) engagement, co-stimulation and distinct cytokine receptor ligation. These three signals, sequential or concurrent, activate and phosphorylate a suite of transcription factors (TFs) that translocate into the nucleus. TFs binding to cis-regulatory elements (promoters, enhancers, insulators and silencers) within gene promoter regions translate extracellular signals to downstream transcriptional programmes. Epigenetic changes to cis-regulatory elements can influence TF binding and the subsequent fate of the cell, adding a level of regulation at this early stage of cell differentiation. Target gene transcription and translation convert naive T cells into mature T cells with distinguishable features, including the expression of specific adhesion molecules and surface receptors, chemokine-producing capacity and activation of often distinguishable metabolic pathways [1]. Differentiated T helper (TH) cells can be defined and distinguished from one another by their primary cytokine-producing capacity, including, but not limited to, interferon (IFN)γ-producing TH1 cells, interleukin (IL)-4-producing TH2 cells, IL-17A-producing TH17 cells and IL-9-secreting TH9 cells. Mature TH cells function to mobilize and activate innate cells, re-enforce TH cell commitment and orchestrate local tissue responses through various lymphokine secretions [2]. In addition to a helper fate for T cells, naive αβ+CD4+ T cells can differentiate into follicular helper T cells (TFH) specialized for B-cell help within marginal zones and germinal centres. In contrast, naive αβ+CD4+ T cells can adopt a regulatory (TREG) function with potent suppressive capacities. Several TREG populations have been described, including Foxp3+ natural TREG (nTREG), which develop in the thymus in response to self-antigen [3], and inducible Foxp3+ (iTREG) cells, which develop in the periphery in response to exogenous antigen and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β [4]. Non-Foxp3-expressing TREG cells have also been identified, including TGF-β-secreting (TH3) [5], IL-10-secreting (TR1) [6] or IL-35-secreting (TR35) TREG [7] cells; however, in this review, we will focus on Foxp3+ TREG cells.

The transcriptional programmes, mediated by a suite of TFs and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) molecules, for the differentiation of TH, TFH or TREG cells are mostly well defined. For example, Tbet, STAT-1 and STAT-4 are required for TH1 differentiation, GATA-3 and STAT-5 for TH2, RORγt and STAT-3 for TH17, PU-1 for TH9 [8], BCL6 for TFH [9] and Foxp3 and STAT-5 for nTREG and iTREG cells. Although Bcl6 and PU-1 are necessary for TFH [9] and TH9 [8] cell differentiation, respectively, they are not sufficient to coordinate the full transcriptional programme, suggesting that other, or additional transcriptional regulators are required. The TF Foxp3 appears to be restricted to TREG cells [10] and is essential for the development, maintenance and function of TREG cells [11–13]. Deficiency in Foxp3 can lead to severe immunopathology with multi-organ lymphoproliferative autoimmune disease identified in spontaneous mutant scurfy mice and in rare cases in humans, known as IPEX syndrome (immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked). For these reasons, Foxp3 has been considered as a master regulator of TREG cell development and function, and is often used as a marker of TREG cells. However, evidence is emerging that Foxp3 alone is not sufficient to regulate the TREG cell phenotype. A combination of computational network inference and proteomics has characterized the highly regulated transcriptional network of co-factors interacting with Foxp3 that are required for TREG cell differentiation [14,15]. Additionally, analysis of genome-wide binding sites and DNAse I sites revealed Foxp3 functions through pre-existing enhancers already bound by co-factors [16], and requires the establishment of a CPG hypomethylation pattern at the Foxp3 binding site [17]. As discussed by others [18], these studies highlight the complexity of signals required for T-cell differentiation, perpetuating the question of adaptation of TREG cells.

Until recently, the doctrine that αβ+CD4+ T cells were restricted to a particular fate (including TH1, TH2, TH9, TH17, TFH or TREG; figure 1) was widely, but not completely, accepted. While the single-fate model is useful, it is often based on in vitro studies, often using supra-physiological stimulation, mitogens, phorbol esters and calcium ionophores or high levels of antigen. Recent studies challenging the single-fate model have highlighted a significant degree of flexibility and plasticity between T-cell destinies in vitro and to a lesser extent in vivo. In this review, we summarize the recent literature reporting T-cell plasticity within and between TH, TFH and TREG cells, describe the current proposed mechanisms, and finally ask whether plasticity within αβ+CD4+ T cells is beneficial or detrimental to immunity.

Figure 1.

T-cell differentiation pathways. Following TCR ligation with appropriate co-stimulation, cytokines activate specific TFs and transcriptional regulators resulting in the differentiation of T cells into various identifiable states. For example IL-4 activates STAT-6 and GATA-3, initiating and repressing a suite of genes characteristic of TH2 cells.

3. The changing profile of helper T cells

3.1. TH17/TH1 conversion

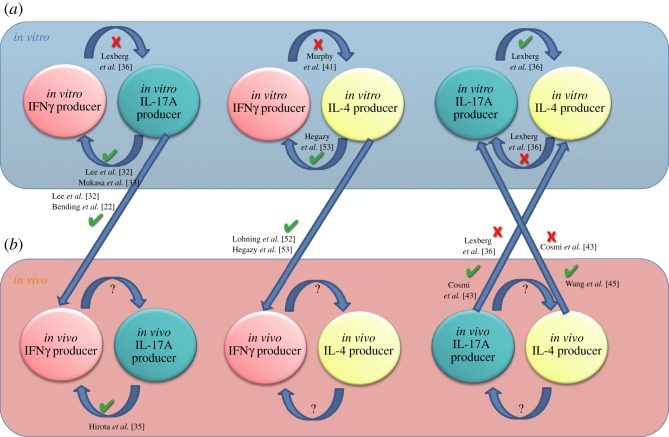

Since the identification of IL-17A-secreting TH17 cells almost a decade ago [19] and the later discovery of the signals required for their development [20,21], TH17 cells have been found to be relatively unstable [22,23], with IL-4 [24], IFNγ [25,26], high-dose TGF-β [21], IL-2 [27] and IL-27 [28] all capable of inhibiting or suppressing TH17 cell differentiation (figure 2). In vitro and ex vivo from mice [29,30] and humans [31], IFNγ and IL-17A co-producing cells were evident, but largely ignored. Addressing this phenomenon in more detail, Lee et al. [32], and later Mukasa et al. [33], reported that cells polarized under TH17 conditions in vitro were capable of producing IFNγ upon secondary culture in TH1 conditions, including IL-12 and blocking antibodies against IL-4. This was not simply an in vitro phenomenon, as in vivo adoptively transferred TH17 cells were able to upregulate and produce IFNγ during colitis [32,34] or in nucleotide oligomerization domain/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mice [22]. Whether TH1, TH17 or an independent pathway gave rise to IFNγ+IL-17A+ cells was unclear. Given that IFNγ can suppress TH17 cells [25,26], it stood to reason that IFNγ+ IL-17A+ cells originated from TH17 cells. Recently, Hirota et al. [35] generated an IL-17A fate reporter mouse allowing the accurate fate-mapping of cells that had transcribed Il17a and thus been through a TH17 programme. Using these fate-mapping mice in a model of multiple sclerosis, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), the authors demonstrated that the majority of pathogenic IFNγ-secreting cells had, at some point, derived from TH17 cells [35], supporting previous studies [22,32,36,37]. In contrast to the EAE model, Hirota et al. [35] further demonstrated that IFNγ-secreting TH1 cells developed independently from TH17 cells following acute cutaneous infection with Candida albicans. It remains unclear whether the difference in conversion reflects a distinction between chronic inflammation (in the EAE model) and acute inflammation (following C. albicans infection), as suggested by the authors, or between autoreactivity and immunity to infection. Feng et al. [34] also identified the conversion of TH17 to TH1 cells in vivo. Mechanistically, the authors identified that IL-17A induced IL-12 secretion from innate cells, facilitating the conversion of TH17 cells to TH1 during experimental colitis. To date, it appears that under appropriate conditions TH17 cells can upregulate TH1 features, including Tbet expression and IFNγ secretion. There is limited evidence to suggest the contrary, that TH1 cells can adopt a TH17 phenotype whether in vitro or in vivo. For example, in vitro studies found that polarized TH1 cells do not readily upregulate RORγt or produce IL-17A when re-cultured in TH17-polarizing cocktails [36]. This may be due to downregulation of the IL-6 receptor on activated T cells [38], a critical component of the TH17-polarizing cytokine cocktail. In vivo, however, this could be overcome through IL-6 presented in trans, bound to IL-6R+ cells, or in complex with soluble IL-6R [39]. Nevertheless, TH1 conversion to a TH17 phenotype does not appear to occur in C57BL/6 mice.

Figure 2.

T helper cell plasticity. Several studies have demonstrated the ability of cytokine-producing cells to change their cytokine-producing profile, under various conditions. In vitro generated (a) IL-17A-producing cells can upregulate IFNγ following re-polarization with IL-12, or following adoptive transfer into mice, as indicated. Similarly, cells that have previously activated an Il-17a programme in vivo (b) can upregulate IFNγ during EAE, as indicated. Whether other cytokine-producing cells display similar plasticity in vivo has not been conclusively demonstrated.

3.2. TH17/TH2 conversion

Similar to TH1 and TH17 cells, there is evidence of cross-regulation between TH2 and TH17 subsets, with TH2-derived IL-4 capable of inhibiting initial TH17 differentiation [25] and subsequent IL-17A secretion from committed TH17 cells [24] (figure 2).

Interestingly, cells undergoing repeated rounds of stimulation in TH17-polarizing conditions in vitro become resistant to the suppressive effects of IL-4, indicating that mature TH17 cells become more rigid or stable.

In vitro- or ex vivo-derived TH17 cells, sorted by fluorescence activated cell sorting using an IL-17A cytokine secretion assay, could produce IL-4 upon secondary culture in TH2 conditions, or upon transfer into helminth-infected mice [40], suggesting that IL-4-sensitive TH17 cells can actively convert into IL-4-secreting TH2 cells. A separate study suggested that TH17 cells were more rigid, with IL-17A-producing T cells isolated ex vivo refractory to TH2 conversion when re-stimulated with IL-4 [36]. Whether the stage or maturity of TH17 differentiation, as suggested above [41], antigen exposure and specificity or receptor expression distinguishes these studies was unclear from the reports. The hypothesis that TH17 cells can convert to TH2 cells is further supported by in vivo observations, mainly in the context of lung inflammation [42,43]. IL-13+IL-17A+ CD4+ T cells were observed in the lungs and draining lymph nodes of mice following repeated administration of ovalbumin (OVA)-pulsed dendritic cells. Co-culture of OVA-pulsed dendritic cells with in vitro-polarized TH17, but not TH2, cells led to the development of an IL-17A+IL-13+ TH population, indirectly suggesting that at least in this model TH17 cells could take on a TH2-like phenotype, but that TH2 cells could not adopt a TH17-like phenotype [42].

In vitro observations also support the notion that TH17 cells can be re-programmed into TH2 cells, but not vice versa [36]. The transcriptional repressor growth factor independent 1 (Gfi-1) can partially explain the lack of TH2 to TH17 conversion. Gfi-1 is induced by IL-4, stabilizing TH2 cells. However, Gfi-1-deficient TH2 cells were able to produce IL-17A in secondary TH17 culture conditions [44]. The authors elucidated, through chromatin immunoprecipitation (CHIP) analysis, that Gfi-1 modifies TH17-associated genes, Rorc and Il23r, preventing their transcription. Thus, activation and IL-4-induced Gfi-1 in TH2 cells serves to promote TH2 cell differentiation and prevent TH17-associated gene transcription. IL-17A+IL-4+ double-producing cells have also been observed within the CCR6+CD161+CD4+ population in humans. Notably, IL-17A+IL-4+ cells were increased among patients with chronic asthma. Culturing human memory TH17 cells with IL-4 led to the induction of IL-17A+IL-4+ cells, while culturing TH2 clones with IL-23 and IL-1β did not [43], similar to the murine studies mentioned above. In contrast, one study identified that IL-17A+IL-4+ memory CRTH2+CCR6+CD4+ cells could be generated from ‘TH2’ (CCR6–CRTH2+CD4+) cells in the presence of IL-1β, IL-6 or IL-21 (or most potently, a combination of all three cytokines and not IL-23). If CCR6–CRTH2+CD4+ cells are bona fide TH2 cells, then this study indicates that TH2 cells are capable of adopting a TH17 profile [45]. The overwhelming evidence from both human and murine studies indicates that TH17 cells, either generated in vitro or in vivo, can adopt a TH2 phenotype whether re-cultured in vitro or adoptively transferred in vivo, with less evidence to support TH2 conversion into TH17 cells.

3.3. TH1/TH2 conversion

The relationship between TH1 and TH2 cells has been the subject of a vast amount of research. Notably, there is much evidence to suggest that TH1 and TH2 cells cross-regulate one another (figure 2). For example, in vitro studies show that TH2-associated GATA-3 inhibits TH1-related IFNγ [46] and TH1-associated Tbet inhibits TH2-related GATA-3 [47]. It has also been demonstrated that after repeated rounds of stimulation in vitro, TH1 and TH2 cells lose their ability to interconvert [41]; that is, TH1 and TH2 cells are less plastic following more rounds of cell division [48]. One simple explanation for this is the downregulation of IL-12Rβ expression on TH2 cells that was shown in vitro [49], rendering TH2 cells un-responsive to lL-12; however, this has been later challenged [50].

Furthermore, in vitro cells may be substantially different from in vivo cells, as IFNγ+IL-4+ cells can be readily observed in vivo in mice [51]. As a proof-of-principle using murine transgenic TCR-restricted T cells, in vitro-polarized, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)-specific TH1 or TH2 cells could give rise to comparable frequencies of IFNγ-producing cells following LCMV infection. Interestingly, the TH2-polarized cells gave rise to a substantial population of cells co-expressing IL-4 and IFNγ [52]. The conversion of LCMV-specific TH2 cells required TCR stimulation as well as the presence of type I and type II interferons [53]. The authors also report a substantial population of IFNγ-producing cells developing from in vitro-derived TH2 cells when cultured in secondary conditions containing IL-12, IFNγ and IFNα/β [53]. In these studies, it is possible that not all adoptively transferred in vitro TH2 cells were fully committed TH2 cells and that TCR-restricted T cells do not reflect natural polyclonal T-cell populations. Nevertheless, these data not only highlight the ability of TH2 cells to become IFNγ-secreting cells, but also highlight that factors present in vivo, which are not common constituents of in vitro culture systems, such as type 1 interferons, can clearly contribute to TH plasticity.

3.4. IL-9-secreting T cells (TH9)

In addition to the ability of TH2 cells to co-express IFNγ, two reports independently identified the secretion of IL-9 from TH2 cells and suggested that TH2 cells could be re-programmed to produce IL-9. These reports led to the classification of TH9 cells. These initial studies used IL-4gfp reporter mice to generate TH2 cells in vitro and subsequently identified that TGF-β provided an essential conversion signal to IL-4gfp+ cells. ‘Ex- TH2’ cells downregulated classical TH2 genes (Gata3 and Il4) and upregulated IL-9 [54,55]. The TH2 heritage of IL-9-secreting cells is supported by their requirement for STAT-6 [56,57] and the observation of IL-9-producing T cells in TH2-associated allergic inflammation [58–60]. However, TH9 cells have also been identified in autoimmunity [61] and more recently in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection [62], more commonly associated with TH1/TH17 responses. Whether IL-9-secreting cells are indeed a distinct lineage [63], warranting a ‘TH’ prefix, or simply recently activated TH, as suggested by others [64], or TREG cells [65] remains to be clarified. Candidates for a TH9 ‘master regulator’ have been suggested, however, including PU-1 [8]. Thus, whether IL-9 secretion by TH1, TH2, TH17 or TREG cells constitutes T-cell plasticity or not is unclear at present.

In summary, the ability of TH1, TH2 or TH17 cells to co-express IFNγ, IL-4, IL-17A or IL-9 can be demonstrated in vitro and in more restricted and occasionally contrived situations in vivo. Interestingly, these phenomena have most frequently been observed during hyper-inflammatory disorders, such as autoimmune or allergic pathologies, with the exception of the LCMV studies [52,53]. There is little evidence that TH plasticity is beneficial during immunity to infection, and it could be hypothesized that the occurrence of plasticity contributes to the development of inflammatory disorders.

4. The changing profile and nature of regulatory T cells

The stability of Foxp3+ TREG cells has been, and continues to be, enthusiastically debated, especially as TREG-based therapies move closer to the clinic [66–68]. Two novel areas of TREG cell biology, TREG specialization and TREG instability, are fuelling the debate on TREG plasticity. In an attempt to reconcile the debate, Miyao et al. [69] developed an innovative Foxp3GFPCreROSA26RFP reporter mouse, which allowed the authors to fate-map cells that had previously expressed Foxp3 (RFP+) in addition to identifying those cells currently transcribing Foxp3 (GFP+). Through a series of adoptive transfer experiments, the authors propose a heterogeneity model identifying populations of both unstable ‘exFoxp3+’ cells which transiently upregulate Foxp3 following activation without adopting suppressor function (Foxp3+ non-TREG cells) and populations of stable Foxp3+ TREG cells. The authors also identify that in the periphery, unstable Foxp3+ cells were CD25– or CD25lo, whereas more stable Foxp3+ TREG cells were CD25hi. Nevertheless, there is substantial evidence that Foxp3+ T cells, whether CD25hi or CD25int, that have lost Foxp3 expression adopt important biological functions, which we summarize below [70]. It is important to note that some of the studies described may be compromised by the use of the Foxp3gfp(Foxp3tm2Ayr) reporter knockin mice. In two separate observations, the EGFP–Foxp3 fusion was shown to disrupt the transcriptional landscape of the TREG cell and therefore affect both the frequency of TREGs and their suppressive properties [71,72]. We indicate, where possible, in the studies mentioned below whether inducible or natural TREG cells were studied; however, in many cases it was not always clear.

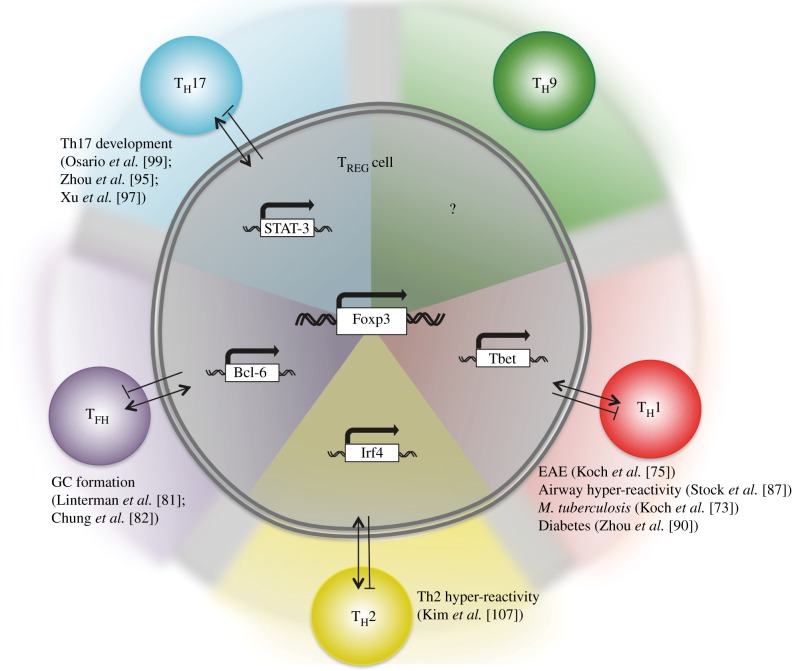

4.1. TREG specialization: co-expression of multiple transcription factors

Recent studies have revealed that multiple TFs are co-expressed in Foxp3+ TREG cells, and essential for TREG function, including several TFs associated with TH cell phenotypes. For example, Koch et al. [73] identified a population of Foxp3+ TREG cells that co-expressed the TH1-associated TF Tbet and the chemokine receptor CXCR3 during M. tuberculosis infection in mice. Functionally, Tbet expression in TREG cells was required for the proliferation of TREG cells in vitro and in vivo. Concordant with this, Tbet-deficient TREG cells transferred into scurfy mice were unable to control TH1 cells. This phenomenon of IFNγ-secreting Foxp3+ cells is further supported and extended in a recent study identifying that IFNγ secretion by Foxp3+ cells was necessary for their regulatory function in a model of graft-versus-host disease [74,75].

Similarly, IRF4, a TF involved in several TH cell subsets, particularly TH2 and TH9 cells [21,76], has been identified in Foxp3+ TREG cells. Significantly, mice lacking Irf4 in Foxp3+ TREG cells failed to control spontaneous TH2-mediated pathologies [77]. Further work from the Rudensky laboratory identified that STAT-3, a TF required for TH17 cells [78], was required for Foxp3+ TREG cells to control TH17 cells in mice [79], confirming previous in vivo observations identifying the requirement of STAT-3 for TREG function [80]. Finally, TFH cells are also regulated by a subset of specialized Foxp3+ TREG cells that co-expressed Bcl6, the same TF required for TFH cell development [81,82] (figure 3). Interestingly, Cipolletta et al. [83] describe a specialized population of Foxp3+ TREG cells resident in visceral adipose tissue (VAT) expressing the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ. These TREG cells play a unique role in suppressing obesity-induced VAT inflammation; however, the mechanism of suppression by these TREG cells is still unclear. Collectively, these studies indicate that TREG cells become functionally specialized to control distinct TH and TFH responses, and perhaps in response to cues from distinct anatomical sites. Secondly, these studies show that TREG cells co-opt similar TF-dependent pathways to the TH cells they regulate. Of note, GATA-3 expression has also been widely reported in Foxp3-expressing cells [84]; however, unlike the focused TH1-, TH2-, TH17- or TFH-controlling Foxp3+ cells described above, GATA-3 was broadly required for stable Foxp3 expression and general TREG function [85,86].

Figure 3.

TREG specialization and plasticity. TREG cells can co-express T helper cell lineage-defining TFs, such as Tbet and Foxp3 (red, lower right segment), during various infectious or inflammatory scenarios. This specialization appears to fine tune TREG cells to more effectively regulate the corresponding effector TH cell. For example Tbet+Foxp3+ TREG cells can potently suppress Tbet+ TH1 cells. Thus, the co-expression of various TFs is required to confer the appropriate and necessary regulatory programme. Whether these hybrid ‘specialized’ TREG cells are intermediate cells in between the TH to TREG conversion (indicated by arrows in figure), or a stable population is unclear. GC, germinal centre.

5. TREG instability: conversion to T effector phenotypes

5.1. TREG/TH1 conversion

The relationship between TH1 and TREG was first described in a study that identified a population of OVA-specific TH1-related Foxp3+ TREG, which produced IL-10 and IFNγ, co-expressed Tbet and Foxp3 and had the capacity to suppress allergen-induced airway hyper-reactivity [87]. The ontogeny of Tbet+Foxp3+ cells in this study, as in others, was unclear. Evidence of Foxp3+ TREG cells converting into IFNγ-producing TH1 cells has been reported in several systems. Firstly, Foxp3 deletion in mature TREG cells in vivo led to the development of pro-inflammatory TH cells secreting IL-2 and IFNγ [88], indicating that Foxp3+ actively represses Tbet and a TH1 programme. Functionally, transfer of these Foxp3-deficient ‘TREG’ cells into lymphopenic hosts led to severe autoimmunity, indicating that these cells acquired pathogenic potential and retained self-antigen specificity [88]. In a separate study, 50 per cent of adoptively transferred natural Foxp3+ TREG cells transferred into lymphopenic mice lost Foxp3 expression and up to 25 per cent started producing tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IFNγ or IL-4 [89]. Similarly, Zhou et al. [90] identified a population of unstable Foxp3+ cells in healthy mice that adopted a TH1-like phenotype and were partially responsible for islet cell destruction and the development of diabetes. Collectively, these studies indicate that during lymphopenia [89], Foxp3 deletion [88] or autoimmunity [90], a fraction of TREG cells could acquire a pro-inflammatory IFNγ-secreting phenotype. Similarly, during lethal enteric Toxoplasma gondii infection, Foxp3+ cells lost their TREG phenotype and converted into pathogenic IFNγ-secreting cells [91]. The conversion of TREG cells into IFNγ+ cells, but not IFNγ+ cells into Foxp3+ cells, is supported by a study by Feng et al. [92] who identified that microbiota antigen-specific inducible Foxp3+ TREG cells could upregulate IFNγ in response to the TH1-polarizing cytokine IL-12 [92]. Furthermore, these IFNγ+Foxp3+ cells retained regulatory properties, before full conversion into pathogenic, non-regulatory, IFNγ+ cells. In both of these studies, IL-12 was identified as a critical component of IFNγ production by Foxp3+ cells.

In humans, although Foxp3 is not an exclusive marker of TREG cells [93], a population of human CD4+CD127loCD25+ T cells, which expressed Foxp3, were found to produce IFNγ. These putative regulatory cells were present at higher levels in patients with type 1 diabetes and possessed mild suppressive properties, although reduced suppressor function compared with IFNγ–TREG cells [94]. Whether Foxp3 expression was only transiently expressed, a feature common to recently activated human TH cells [93], or stably expressed in a TREG cell was unclear in this study. Collectively, these murine and human studies suggest that TREG cells, which maintain peripheral tolerance, can convert into pathogenic TH1-associated cells capable of causing autoimmunity and lethal inflammation. The mechanisms for conversion have not been completely elucidated in these systems. It is not yet clear whether plasticity in various systems relies on common mechanisms or is specific to the local micro-environment. Potential mechanisms of plasticity are discussed later in this review.

5.2. TREG/TH17 conversion

The reciprocal relationship between IL-17A-secreting RORγt+ cells and inducible Foxp3+ TREG cells has been widely reported. For example, TGF-β promotes the expression of both Foxp3 and RORγt . However, Foxp3 directly inhibits RORγt in vitro leading to a regulatory T-cell phenotype [95]. The initial observation that innate cell-derived IL-6 could block TGF-β-mediated iTREG induction and iTREG-mediated suppression [76] raised the possibility that iTREG cell development or function could be interrupted by inflammatory cytokines. Several years later, two independent groups [20,21] identified that IL-6 and TGF-β induced TH17 differentiation, providing a divergent molecular mechanism of iTREG and TH17 development. Thus, TGF-β in the presence or absence of IL-6 [96] can act as a critical tipping point directing the development of TH17 or TREG cells, respectively. The balance between iTREG and TH17 cells may be intricately regulated as Foxp3+ TREG cell-derived TGF-β [97] and TREG-induced IL-6 from mast cells [58] can promote de novo TH17 differentiation in naive T cells.

Several reports have identified cells in vivo co-expressing RORγt and Foxp3 [95,98] with the ability to differentiate into pathogenic RORγt+Foxp3+IL-17A+ [99] or regulatory RORγt+Foxp3+IL-10+ [98] cells. The developmental crossroads may be regulated by IL-6 or other innate cytokines as rIL-6-exposed Foxp3+ TREG cells can upregulate IL-17A in vitro [97]. Whether in vivo Foxp3+ TREG cells are similarly responsive to IL-6, and IL-12 as described above [57] remains to be demonstrated. The clearest description of IL-17A-producing T cells developing from a Foxp3+ source was identified using fate-mapping Foxp3Cre mice, labelling cells that had previously transcribed Foxp3. In this study, 22 per cent of IL-17A-producing cells in the small intestine had expressed Foxp3 at some point in their development [90].

In addition to IL-6, which can function as a molecular switch between iTREG and TH17 cell differentiation, as described above, Sharma et al. [100] identified that indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) [101], a tryptophan-catabolizing enzyme produced by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and potentially other cells, maintains the TREG/TH17 balance in tumour-draining lymph nodes by regulating IL-6 production. Inhibition of IDO led to increased IL-6 and the conversion of Foxp3+ TREG cells into polyfunctional IL-2, TNF-α, IL-22 and IL-17A-secreting cells. Similar TREG to TH17 conversions have been observed in human T cells, with TREG cells cultured in vitro with IL-2 and IL-15 losing Foxp3 expression and secreting IL-17A, IL-22, IFNγ and IL-21 [59]. Using TREG cell clones, Beriou et al. [102] were able to further demonstrate that Foxp3+ IL-17A+ TREG cells retained the capacity to suppress or secrete IL-17A, depending upon the stimulation. Foxp3+ IL-17A+ clones stimulated with IL-1β and IL-6 produced IL-17A, whereas Foxp3+IL-17A+ clones treated with IL-2 were potent suppressive cells [102], suggesting a dynamic switch between regulatory and effector functions in response to environmental cytokines.

Foxp3+CD25+CD45RA+CCR6+ cells that co-express RORγt, with the capacity to secrete IL-17A following re-stimulation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate/ionomycin or pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-2, IL-21 and IL-23 have also been identified in the peripheral blood [103] and tonsils [104] of healthy donors. These cells were also able to suppress CD4+ T cells via cell contact-dependent mechanisms. Given the close developmental relationship between iTREG and TH17 cells [95] and the intimate cross-regulation by RORγt and Foxp3, the conversion between TH17 and TREG cells may not be too surprising. However, the opposing function of these cell types would require tightly regulated mechanisms, critical to preventing regulators of autoimmunity converting into effectors. Whether a breakdown in these regulatory pathways, such as the IDO/IL-6 pathway described above [100], underpins the development of autoreactivity, in addition to tumour immunosurveillance, is unclear.

5.3. TREG/TH2 conversion

The ability of TREG cells to convert into IL-4-secreting TH2 cells has also been reported. The Foxp3IRES-luciferase-IRES-eGFP (FILIG) mouse, which has a 5–10% reduction in Foxp3 expression in CD4+ T cells, develops an aggressive autoimmune disorder and wasting disease. Interestingly, cells from FILIG mice that had reduced Foxp3 expression lost their suppressive activity and started producing TH2 cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-13, and to a lesser extent IL-2, IFNγ and IL-17A [105], similar to Foxp3-ablated TREG cells [88]. More conclusively, adoptive transfer of FILIG TREG cells, with attenuated levels of Foxp3, into TCRα–/– or RAG2–/– mice preferentially differentiated into TH2 cells and produced IL-4 [106]. Mechanistically, TREG to TH2 cell conversion was dependent on GATA-3 and independent of STAT-6 signalling. However, for stable IL-4 production by ‘exFoxp3’ cells an IL-4/STAT-6/GATA-3 loop was required [85,106]. There may be a dynamic relationship between TH2 and TREG cells, as TH2 cells stimulated with TGF-β, retinoic acid and antibodies to IL-4 and IFNγ in vitro downregulated TH2 signature genes, lost production of IL-4 and IL-13 and adopted a Foxp3+ regulatory phenotype [107]. Furthermore, these converted TH2-derived memory Foxp3+ T cells could suppress TH2-mediated airway hyper-reactivity when adoptively transferred in vivo, suggesting that the converted ex-TH2 cells could gain not only Foxp3 expression but also suppressive function [107].

5.4. TREG/TFH conversion

Finally, the plasticity or transient nature of Foxp3 expression in some TREG cells permitted the conversion of TREG cells to TFH cells. Under lymphopenic conditions, adoptively transferred Foxp3+ TREG cells downregulated Foxp3 expression in the Peyer's patches clustered around germinal centres and expressed TFH cell-associated markers CXCR5, IL-21 and Bcl6 [108]. As described above, specialized TREG cells that upregulated Bcl6 and CXCR5 acquired the ability to preferentially regulate TFH cells [81,82]. Whether some TFH cells retain plasticity, with the ability to self-regulate by upregulating Foxp3, or whether all three populations (TFH, TREG and TFH/TREG) develop independently is unclear.

In summary, it is clear that some, possibly CD25– or CD25lo Foxp3+, cells [69] display elements of plasticity; losing Foxp3 expression and adopting helper or follicular helper phenotypes with distinct cytokine-producing capacity. In the light of the recent study by Miyao et al. [69], whether exFoxp3 cells described above originate from peripheral Foxp3+CD25– or Foxp3+CD25lo populations, with variable IL-2-responsiveness, or not is unclear. These data would imply that IL-2 signalling in TREG cells is not only required to maintain TREG stability, but also to prevent plasticity and TH cell conversion. In keeping with this, in vivo IL-2 blockade resulted in a loss of peripheral Foxp3+ cells and the development of autoimmune gastritis [109]. Whether the pathogenic T cells, which caused gastritis in this model, originated from a Foxp3+ population upon IL-2 depletion was unclear.

6. Potential mechanisms of T-cell plasticity

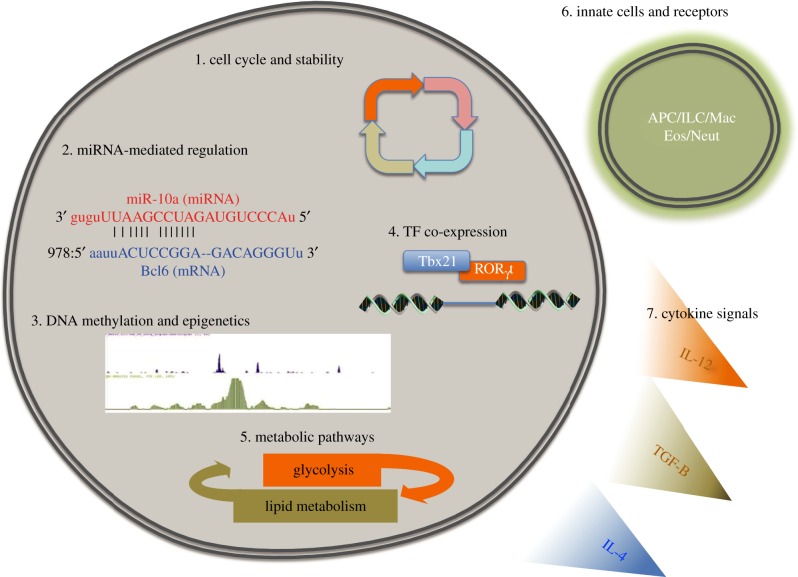

From the studies mentioned above, the ability of CD4+ T cells to change their phenotype is clear. Whether there is progression from a less stable to a more stable state, as suggested by others [110], or whether the T-cell phenotype is simply a reflection of the transient micro-environment has yet to be determined. Although not directly tested in any of the studies mentioned throughout this review, whether the genetic background of mice used contributes to plasticity or not is unclear and yet to be tested. With the advent of well-defined genetic tools, such as the international Collaborative Cross [111], dissecting genetic determinants of T-cell responsiveness will now be much easier. However, to date, several mechanisms that influence T-cell plasticity have been proposed, generally separable into extrinsic and intrinsic pathways (see figure 4).

Figure 4.

Potential mechanisms of T-cell plasticity. Various mechanisms of T-cell plasticity have been tested, suggested and loosely implied. Intrinsic mechanisms, (1) including the stage of TH cell maturation may be inversely correlated to plasticity. (2) Post-transcriptional regulation by small RNA molecules, including miRNAs, can dramatically alter the T-cell phenotype. (3 and 4) Changing TF expression and activation with permissive epigenetic marks at TF binding sites can re-programme entire gene programmes. (5) A change in nutrient availability may trigger changes in intracellular metabolic pathways and the resultant T-cell phenotype and function. (6 and 7) Extracellular influences, including interactions with innate cell receptors or triggering of cytokine signalling pathways may dynamically alter cytokine receptor expression on T cells, making them permissive to subsequent re-programming signals. APC, antigen-presenting cell; Eos, eosinophil; ILC, innate-like helper cells; Mac, macrophage; Neut, neutrophil.

7. Cell extrinsic mechanisms of T-cell conversion

7.1. Accessory innate cells and innate receptors

Although often bypassed using in vitro T-cell assays, antigen-presenting cells (APCs) displaying various co-stimulatory molecules on their surface translate innate antigen recognition signals into the appropriate instructions for T cells. It has been well documented that high antigen doses, and higher affinity peptides, polarize responding naive T cells into TH1 cells, while low antigen doses, and lower affinity peptides, favour TH2 polarization [112,113]. It is therefore conceivable that the TH cell response may transition from a pro-inflammatory TH1-, and possibly TH17-, dominant phenotype during antigen abundance, or high pathogen load in the case of infection, when cells are also potentially refractory to TREG-mediated suppression [114], into a TH2 phenotype as the antigen is reduced. Beyond TCR–major histocompatibility complex II–peptide interactions, co-stimulatory molecules on APCs, particularly the B7 family members, which greatly influence T-cell differentiation [112,115,116], may also have the potential to transform and re-polarize differentiated TH cells by modulating cytokine responsiveness [117]. Through germline encoded receptors, including toll-like (TLR) and NOD-like receptors, APCs can influence the resultant T-cell response. Ligation of specific TLRs on various innate cells elicits divergent co-stimulatory molecule expression and cytokine secretion. This feature of highly responsive innate receptors on APCs is currently being therapeutically targeted to deviate adaptive immune responses during cancer, and infectious and allergic diseases (reviewed by Kanzler et al. [118]). For example, treatment of allergen-sensitive mice, which have TH2-polarized TH cells, with CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides that stimulate TLR9, downregulated B7.2 (CD86) in lung tissue and deviated TH2 responses towards TH1 responses [119]. Whether TLR9 ligation on APCs relayed a signal to convert TH2 cells into TH1 cells was not explored. Furthermore, T cells themselves possess the same germline-encoded innate recognition receptors as innate cells. In vitro TLR4 ligation on TH cells during T-cell differentiation did not preferentially alter TH1, TH2, TH17 or iTREG cytokine responses, but prolonged survival and expansion, suggesting a common TLR4-driven signalling pathway in TH cell subsets [120]. However, in vivo experiments highlighted the requirement of TLR4 ligation for TH1 and TH17-mediated disease. Disruption of TLR signalling, by deleting the essential downstream adaptor MyD88 in T cells, compromised protective TH1-mediated immunity to T. gondii [121]. Using an EAE model and TLR4 [120] or TLR2-deficient [122] CD4 T cells, TH17 and TH1-dependent disease was also significantly abrogated. Further support for TLR4 signalling in T cells has been reported in a model of colitis [123], where TLR4/IL-10-deficient T cells were more pathogenic, compared with IL-10-deficent cells. Although the extent of TLR signalling on T-cell stability and plasticity has not been reported, given the requirement for TLR4-mediated signals for TH17 and TH1 responses, TLR signalling could be an influential trigger in T-cell phenotype decisions.

Other innate cells, including IL-4-secreting basophils, neutrophils in various stages of apoptosis and inducible nitric oxide-producing macrophages, can promote TH2 [124,125], TH17 [126] or TH1 [127] differentiation, respectively, and may also contribute to T-cell plasticity. Finally, the emerging field of innate-like helper cells (ILCs), which appear to mirror TH cell subsets [128], can influence naive T-cell differentiation [129], and potentially differentiate T cells promoting plasticity. The high levels of IFNγ, IL-17A and IL-22 or IL-5 and IL-13 secreted by the three main populations of ILCs have the potential to deviate T-cell and non-T-cell responses.

7.2. Cytokine micro-environment and cytokine receptor regulation

The cytokine micro-environment can activate, inhibit and directly modify differentiated TH cells. With respect to T-cell plasticity, type-1 IFNs can induce the expression of IL-12R on TH2 cells, allowing the necessary IL-12 signals to induce Tbet and IFNγ secretion [53] and subsequent TH2 to TH1 conversion. This mechanism of type-1 IFN-mediated TH2 to TH1 conversion via cytokine receptor regulation supports observations made over 10 years ago identifying that IFNγ and IFNα mediate the decay of IL-4R [130]. Regulation of IL-12R and sensitivity to the potent effects of IL-12 [131] and IL-18 [132] has long been appreciated in the differentiation of TH1 and TH2 cells [49]. Initial studies demonstrated that TH2 cells downregulate IL-12R, leaving cells refractory to IL-12, while TH1 cells operate positive re-enforcement with IFNγ-mediated STAT-1 activating Tbet and up-regulating IL-12R expression [133]. In our unpublished observations, and reported by others [50], downregulation of IL-12R did not completely abrogate IL-12 signalling in TH2 cells. IL-2, an important T-cell growth factor for all other T cells, downregulates IL-7R [134] and IL-6R, and upregulates IL-4R and IL-12Rβ2, inhibiting TH17 generation [27] but facilitating TH1 and TH2 differentiation [135]. Furthermore, IL-2 is tightly regulated in TH17 cells by Aiolos, a member of the Ikaros family of TFs [136], preventing IL-2 production and the potential for IL-2 to antagonize TH17 development. Similarly, many studies have identified the ability of IL-27 to antagonize TH17 differentiation and effector function in a STAT-1-dependent manner [28,137–141] and increase responsiveness to IL-12 [142]. The combined ability of IL-12 signalling to re-direct TGF-β-orchestrated TREG or TH17 programmes [131], coupled with multiple pathways regulating IL-12 receptor expression and responsiveness, may explain why TH1 cells may be more stable. Thus, the conversion of TH17 cells into TH1, TH2 or TREG cells may involve an IL-2–STAT-5 signal, facilitated by IL-27–STAT-1 signals for conversion into TH1 cells. Whether canonical cytokine signalling pathways are required for TH cell conversion, such as IL-4, IL-12 and IL-6 for TH2, TH1 and TH17 responses, respectively, is unclear. In the absence of IL-4 and IL-13, TH1 cells converted into TH2 cells during hookworm infection [40], suggesting that a non-canonical pathway may exist at least for TH1 to TH2 conversion. Collectively, these studies indicate that the local cytokine environment can modify the expression and responsiveness of various cytokine receptors, rendering differentiated T cells susceptible to alternative differentiation pathways.

7.3. Nutrient availability and metabolic pathways

Throughout T-cell development, differentiation and function, metabolic needs are intimately linked [1]. Following activation, helper T cells rapidly upregulate glucose uptake and glycolysis [143,144]. In contrast, regulatory T cells upregulate lipid oxidative metabolism [145], with less glucose uptake and glycolysis. Inhibition of either of these pathways prevents activation, proliferation, cytokine secretion and cellular function [146]. Furthermore, the metabolic needs and pathways of different TH cells diverge, providing another environmental cue that may influence TH cell phenotype switching. For example, distinct phosphoinositide 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways [147], via two mTOR complexes, mTORC1 or mTORC2, are employed by TH1 and TH17 or TH2 cells, respectively [148]. Additionally, small concentrations of the small molecule halofuginone, which induces an amino acid starvation response, can limit TH17 but not TH1, TH2 or iTREG polarization in vitro [149]. Hypoxia-induced factor (HIF)1α and cMyc, two TFs that regulate glycolysis [150], can also modulate the balance between TH17 and TREG differentiation by controlling glycolytic metabolism [151]. Concordantly, mice with HIF1α-deficient T cells, with subsequently compromised glycolysis, have increased TREG cells and are protected from T-cell-mediated autoimmunity [152]. Thus, at the simplest level, shuttling between glycolysis and lipid oxidation pathways can favour T-cell differentiation pathways between TH and TREG cells. It is clear that the T cells have specific metabolic requirements and that these requirements differ between TH and TREG subsets; it is yet undetermined whether these metabolic pathways are important for T-cell plasticity in vivo.

8. Potential cell-intrinsic mechanisms of T-cell conversion

8.1. Cell cycle and phenotype stability

Soon after the description of the TH1 and TH2 lineages, it was reported that T cells gradually become more fixed in their phenotype after several rounds of differentiation and lose their ability to acquire other TH phenotypes [41,48]. This observation holds true with recent reports identifying that mature TH17 cells, compared with immature TH17 cells, became less responsive to IL-4 [24]. Together, these studies imply that cytokine positive, early differentiating cells are more plastic than their mature counterparts. Indeed, memory TH17 cells were shown to have a stable phenotype [36]. Nevertheless, it has been reported that some antigen-specific memory CD4 cells show substantial plasticity between TH1 and TH2 phenotypes [153]. Thus, TH plasticity may be intimately linked to not only cell cycle, but also memory status.

8.2. microRNA-mediated control of T-cell phenotype

microRNAs (miRNAs) are a family of small non-coding RNAs that provide post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. There is accumulating evidence that miRNAs are critical in regulating the expression of key molecules in TH and TREG subsets. CD4 T cells deficient in dicer, an enzyme required for miRNA biogenesis, had dysregulated cytokine production following in vitro culture, including the co-expression of IFNγ and IL-4 in TH2 culture conditions [154]. Deletion of another component of the miRNA machinery, drosha, specifically in Foxp3-expressing cells resulted in autoimmunity and overexpression of IFNγ and IL-4 [155]. Specific miRNAs that regulate CD4 T-cell phenotypes have also been identified. For example, miR-29, which targets Tbet, Eomesodermin and Ifnγ [156,157], critically controls TH1 cell development. miR-10a regulates Bcl-6 in TREG cells, preventing the development of a TFH cell phenotype from TREG cells [158]. Finally, miR-326 promotes TH17 differentiation, with miR-326 expression correlating with disease severity in multiple sclerosis patients [159]. Thus, it is clear that miRNAs are key regulators of T-cell differentiation, and it is likely that miRNAs could regulate both upstream pathways (cytokine receptor, signalling pathways and TF expression) and downstream (effector cytokine production) features of T cells contributing to lineage stability and plasticity, as indicated with miR-10a in TREG cells [158].

8.3. Transcription factor dosing and dominance

For TFs to maintain activated and repressed gene programmes, the continuous activation, phosphorylation and presence of TFs in the nucleus is often required. For example in the case of TREG cells, ablation of Foxp3 in TREG cells results in the loss of Foxp3-driven suppressor function [88]. Furthermore, decreased Foxp3 expression converts TREG cells into pathogenic effector cells [105], suggesting that a significant function of Foxp3 is to repress the development of TH cell-associated responses. TFs can also function to reinforce TH phenotypes, as in TH1 cells where IFNγ promotes Tbet via STAT-1, which in turn promotes the expression of the IL-12 receptor [132,133]. The importance of TF activation in T-cell phenotypes is supported by forced/ectopic expression experiments. Ectopic expression of Foxp3 in CD4+ non-TREG cells leads to acquisition of suppressive function [10,12,160]. Similarly, forced expression of STAT-6 [161], Tbet [162] or RORγt [29] results in TH2, TH1 or TH17 cell development, respectively. Ectopic expression of Tbet in TH2 cells results in IFNγ production [101,133], suggesting that Tbet can override the transcriptional programme in TH2 cells. Furthermore, there is considerable cross-regulation between TFs in T-cell subsets. For example, Foxp3 can inhibit RORγt function [95], Tbet negatively regulates GATA-3 [47] and GATA-3 downregulates STAT-4 [163]. STAT-5 can also repress the TFH phenotype by suppressing the expression of Bcl-6, among others [164,165]. Thus, a hierarchy of TF expression and activation may ultimately dictate the resultant T-cell phenotype. From these ectopic expression experiments, if sufficient signals induce and activate TFs, then the phenotype of the cell can be re-programmed. It is conceivable, therefore, that modifications of TF expression could be intimately linked with T-cell plasticity. Indeed, it has been shown that in polarized TH1 cells, Tbet forms a complex with Bcl-6, preventing its function. Upon limiting IL-2 conditions, the amount of Bcl-6 in the TH1 cells increases and the cells are able to express TFH-associated genes [166]. Similarly, as described above, expression of Gfi-1 in TH2 cells prevents the development of a TH17 phenotype; deletion of Gfi-1 allowed TH2 cells to adopt a TH17 phenotype [44].

The existence of cells co-expressing Foxp3 along with TH cell-associated TFs, including Tbet, GATA-3 or RORγt (described in previous sections), calls into question whether there is a regulated balance between TFs (TF dosage) resulting in either effector, effector/regulatory or regulatory function. Furthermore, the ontogeny of these cells remains to be conclusively clarified, whether dual TF-expressing cells derive from TH or TREG progeny, or independently. If dual TF-expressing TREG cells derive from TH cells, the upregulation of Foxp3 may represent a late stage in TH cell differentiation. In this scenario, ‘ex-TH’ cells would retain characteristics of their TH cell past, including antigen-specificity and appropriate homing receptors. The alternative, that dual TF expressing cells originate from a Foxp3+ TREG past, is also plausible and has been reported in several experimental systems.

8.4. Epigenetic modifications

Recent studies have combined gene expression profiling with ChIP-Seq and high-throughput sequencing to investigate the chromatin state in resting and effector T cells [167,168]. These studies have revealed important insights into the mechanisms of T-cell plasticity and stability. For example, the proximal promoter of Ifnγ has permissive methylation marks in TH1 cells, but repressive marks in TH2 and TH17 cells, indicating that specific effector functions may be regulated through epigenetics. Interestingly, in various TH cells, bivalent marks allowing enhancement or repression were found at TF genes, including bivalent marks at Tbet and Gata3 in TH17 cells, at Gata3 in TH1 cells, at Tbet in TH2 cells, and at Tbet, Gata3, and Rorc in TREG cells. This suggests the potential for substantial reversibility at the TF level [32,168]. TH subsets also show positive marks on the Bcl-6 locus, providing the possibility for TH cells to take on a TFH phenotype [169]. In addition, studies using both wild-type and STAT-4 or STAT-6 knockout T cells have revealed that these transcriptional regulators have effects on epigenetic modifications in T cells [170]. Given the bivalent marks at TF genes in TH cells, epigenetic modifications of effector genes, such as Ifnγ, Il17a or Il5 in T cells may be critical regulators of T-cell effector cytokine production. Although epigenetic modifications influence TH cell gene expression, how epigenetic modifications are regulated in T cells is unclear, and therefore how this mechanism would directly contribute to T-cell plasticity is uncertain.

Multiple overlapping mechanisms may all contribute to T-cell plasticity, including epigenetic modifications, post-transcriptional regulation by miRNAs, changes in metabolic activity and activation of TFs.

9. T-cell plasticity in immunity: beneficial or detrimental?

As suggested by others [171], the rapid conversion between TREG and TH cell and within TH cell populations could be a very useful feature of the adaptive immune system. Such dexterity could retain antigen-specificity and subsequent memory, preserve the appropriate tropism and rapidly respond to the changing demands and needs of the local environment. With respect to immunity to infection, we have previously reported that increased resistance to the helminth parasite Schistosoma mansoni following drug treatment and IL-10R blockade led to elevated antigen-specific IFNγ, IL-5 and IL-17A production [172]. Similarly, lethal infection of IL-10-deficient mice with the intestinal whipworm parasite Trichuris muris led to increased parasite-antigen-induced IFNγ and IL-17A [173]. Whether elevated T-cell-derived IFNγ and IL-17A secretions were from TH2 cells (i.e. polyfunctional) or from converted TH2 cells (i.e. plasticity) is yet to be determined. Also, the precise involvement of IL-10 in regulating these responses was not investigated. In highly regulated environments such as the gut and airways, an effector response must be able to mature in response to infection and overcome local regulatory mechanisms. Indeed, the ability to mount a rapid and lethal TH1 response following oral T. gondii infection was due to T-cell plasticity, where Foxp3+ cells converted into pathogenic IFNγ-secreting cells [91]. If plasticity contributed to the observed phenotypes following S. mansoni, T. muris and T. gondii infection, then despite providing superior pathogen control, significant immunopathology developed. However, the plasticity of TH cells without severe consequences has also been observed in several infection models [40,51,53,153], indicating that plasticity, when absolutely necessary, can provide T-cell-mediated immunity. It remains unclear when plasticity is required to combat infection, under physiological conditions. Studies in infectious disease models, however, provide ideal systems to probe T-cell plasticity throughout induction, expansion and resolution of the T-cell response. Several studies have identified the plasticity of T cells during autoimmunity [22,35,94] and allergy [42,45,107]. Whether T-cell plasticity contributes to the pathogenesis or resolution of these immunopathologies is too early to tell. Nevertheless, strategies to deviate T-cell responses in allergy are being pursued, as described above [118].

Currently, there is limited evidence showing TH plasticity occurring in vivo as part of an effective immune response. Over the coming years, as we move beyond phenomenology, there is a need to ask what proficient T cells do, in addition to what T cells can do when forced in vitro. Similarly, the use of a single primary cytokine for fully differentiated and committed TH cells may have over-simplified the complexity and flexibility of T cells. The differences noted between in vitro and in vivo systems in this review emphasize the importance of understanding the limitations of experimental systems. New and improved technical approaches will be essential in future research, especially with regard to identifying mechanisms of plasticity. It is, as yet, unclear which mechanisms contribute to plasticity and whether there are common triggers of plasticity among experimental systems or even between subsets. Undoubtedly, further research in this area will help us comprehend not just the extreme capabilities of the immune system but how the immune response functions best and how this can be harnessed.

10. Acknowledgements

S.M.C., V.S.P. and M.S.W. are funded by the MRC (MRC File Reference number MC_UP_A253_1028) and a Lady TATA foundation grant awarded to M.S.W. We would also like to thank Isobel Okoye, Yashaswini Kannan and Stephanie Czieso for helpful discussions. We apologize to our many colleagues whose important work we did not mention in this review due to space limitations.

References

- 1.Gerriets VA, Rathmell JC. 2012. Metabolic pathways in T cell fate and function. Trends Immunol. 33, 168–173 10.1016/j.it.2012.01.010 (doi:10.1016/j.it.2012.01.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okoye IS, Wilson MS. 2011. CD4+ T helper 2 cells: microbial triggers, differentiation requirements and effector functions. Immunology 134, 368–377 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03497.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03497.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. 1995. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 155, 1151–1164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bluestone JA, Abbas AK. 2003. Natural versus adaptive regulatory T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 253–257 10.1038/nri1032 (doi:10.1038/nri1032) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Kuchroo V, Inobe J, Hafler D, Weiner H. 1994. Regulatory T cell clones induced by oral tolerance: suppression of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Science 265, 1237–1240 10.1126/science.7520605 (doi:10.1126/science.7520605) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groux H, O'Garra A, Bigler M, Rouleau M, Antonenko S, de Vries JE, Roncarolo MG. 1997. A CD4+ T-cell subset inhibits antigen-specific T-cell responses and prevents colitis. Nature 389, 737–742 10.1038/39614 (doi:10.1038/39614) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collison LW, et al. 2007. The inhibitory cytokine IL-35 contributes to regulatory T-cell function. Nature 450, 566–569 10.1038/nature06306 (doi:10.1038/nature06306) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang HC, et al. 2010. The transcription factor PU.1 is required for the development of IL-9-producing T cells and allergic inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 11, 527–534 10.1038/ni.1867 (doi:10.1038/ni.1867) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu D, et al. 2009. The transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 directs T follicular helper cell lineage commitment. Immunity 31, 457–468 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.002 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. 2003. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science 299, 1057–1061 10.1126/science.1079490 (doi:10.1126/science.1079490) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng Y, Rudensky AY. 2007. Foxp3 in control of the regulatory T cell lineage. Nat. Immunol. 8, 457–462 10.1038/ni1455 (doi:10.1038/ni1455) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. 2003. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 4, 330–336 10.1038/ni904 (doi:10.1038/ni904) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko SA, Ramsdell F. 2003. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat. Immunol. 4, 337–342 10.1038/ni909 (doi:10.1038/ni909) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudra D, et al. 2012. Transcription factor Foxp3 and its protein partners form a complex regulatory network. Nat. Immunol. 13, 1010–1019 10.1038/ni.2402 (doi:10.1038/ni.2402) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu W, et al. 2012. A multiply redundant genetic switch ‘locks in’ the transcriptional signature of regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 13, 972–980 10.1038/ni.2420 (doi:10.1038/ni.2420) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samstein RM, et al. 2012. Foxp3 exploits a pre-existent enhancer landscape for regulatory T cell lineage specification. Cell 151, 153–166 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.053 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.053) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohkura N, et al. 2012. T cell receptor stimulation-induced epigenetic changes and Foxp3 expression are independent and complementary events required for Treg cell development. Immunity 37, 785–799 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.010 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hori S. 2012. The Foxp3 interactome: a network perspective of T(reg) cells. Nat. Immunol. 13, 943–945 10.1038/ni.2424 (doi:10.1038/ni.2424) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy CA, Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein W, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA, Sedgwick JD, Cua DJ. 2003. Divergent pro- and antiinflammatory roles for IL-23 and IL-12 in joint autoimmune inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 198, 1951–1957 10.1084/jem.20030896 (doi:10.1084/jem.20030896) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. 2006. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 441, 235–238 10.1038/nature04753 (doi:10.1038/nature04753) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. 2006. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity 24, 179–189 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bending D, De la Pena H, Veldhoen M, Phillips JM, Uyttenhove C, Stockinger B, Cooke A. 2009. Highly purified Th17 cells from BDC2.5NOD mice convert into Th1-like cells in NOD/SCID recipient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 565–572 10.1172/JCI37865 (doi:10.1172/JCI37865) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathur AN, Chang HC, Zisoulis DG, Kapur R, Belladonna ML, Kansas GS, Kaplan MH. 2006. T-bet is a critical determinant in the instability of the IL-17-secreting T-helper phenotype. Blood 108, 1595–1601 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015016 (doi:10.1182/blood-2006-04-015016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooney LA, Towery K, Endres J, Fox DA. 2011. Sensitivity and resistance to regulation by IL-4 during Th17 maturation. J. Immunol. 187, 4440–4450 10.4049/jimmunol.1002860 (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1002860) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Turner H, Murphy TL, Murphy KM, Weaver CT. 2005. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat. Immunol. 6, 1123–1132 10.1038/ni1254 (doi:10.1038/ni1254) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park H, et al. 2005. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat. Immunol. 6, 1133–1141 10.1038/ni1261 (doi:10.1038/ni1261) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laurence A, et al. 2007. Interleukin-2 signaling via STAT5 constrains T helper 17 cell generation. Immunity 26, 371–381 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.009 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amadi-Obi A, Yu CR, Liu X, Mahdi RM, Clarke GL, Nussenblatt RB, Gery I, Lee YS, Egwuagu CE. 2007. TH17 cells contribute to uveitis and scleritis and are expanded by IL-2 and inhibited by IL-27/STAT1. Nat. Med. 13, 711–718 10.1038/nm1585 (doi:10.1038/nm1585) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ, Littman DR. 2006. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell 126, 1121–1133 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luger D, et al. 2008. Either a Th17 or a Th1 effector response can drive autoimmunity: conditions of disease induction affect dominant effector category. J. Exp. Med. 205, 799–810 10.1084/jem.20071258 (doi:10.1084/jem.20071258) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Rivino L, Geginat J, Jarrossay D, Gattorno M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F, Napolitani G. 2007. Surface phenotype and antigenic specificity of human interleukin 17-producing T helper memory cells. Nat. Immunol. 8, 639–646 10.1038/ni1467 (doi:10.1038/ni1467) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee YK, Turner H, Maynard CL, Oliver JR, Chen D, Elson CO, Weaver CT. 2009. Late developmental plasticity in the T helper 17 lineage. Immunity 30, 92–107 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.005 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mukasa R, Balasubramani A, Lee YK, Whitley SK, Weaver BT, Shibata Y, Crawford GE, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. 2010. Epigenetic instability of cytokine and transcription factor gene loci underlies plasticity of the T helper 17 cell lineage. Immunity 32, 616–627 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.016 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng T, Qin H, Wang L, Benveniste EN, Elson CO, Cong Y. 2011. Th17 cells induce colitis and promote Th1 cell responses through IL-17 induction of innate IL-12 and IL-23 production. J. Immunol. 186, 6313–6318 10.4049/jimmunol.1001454 (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1001454) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirota K, et al. 2011. Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat. Immunol. 12, 255–263 10.1038/ni.1993 (doi:10.1038/ni.1993) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lexberg MH, Taubner A, Forster A, Albrecht I, Richter A, Kamradt T, Radbruch A, Chang HD. 2008. Th memory for interleukin-17 expression is stable in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 2654–2664 10.1002/eji.200838541 (doi:10.1002/eji.200838541) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurschus FC, Croxford AL, Heinen AP, Wortge S, Ielo D, Waisman A. 2010. Genetic proof for the transient nature of the Th17 phenotype. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 3336–3346 10.1002/eji.201040755 (doi:10.1002/eji.201040755) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones GW, et al. 2010. Loss of CD4+ T cell IL-6R expression during inflammation underlines a role for IL-6 trans signaling in the local maintenance of Th17 cells. J. Immunol. 184, 2130–2139 10.4049/jimmunol.0901528 (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0901528) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Briso EM, Dienz O, Rincon M. 2008. Cutting edge: soluble IL-6R is produced by IL-6R ectodomain shedding in activated CD4 T cells. J. Immunol. 180, 7102–7106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Panzer M, Sitte S, Wirth S, Drexler I, Sparwasser T, Voehringer D. 2012. Rapid in vivo conversion of effector T cells into Th2 cells during helminth infection. J. Immunol. 188, 615–623 10.4049/jimmunol.1101164 (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1101164) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy E, Shibuya K, Hosken N, Openshaw P, Maino V, Davis K, Murphy K, O'Garra A. 1996. Reversibility of T helper 1 and 2 populations is lost after long-term stimulation. J. Exp. Med. 183, 901–913 10.1084/jem.183.3.901 (doi:10.1084/jem.183.3.901) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raymond M, Van VQ, Wakahara K, Rubio M, Sarfati M. 2011. Lung dendritic cells induce T(H)17 cells that produce T(H)2 cytokines, express GATA-3, and promote airway inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 128, 192–201 e6 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.029 (doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cosmi L, et al. 2010. Identification of a novel subset of human circulating memory CD4+ T cells that produce both IL-17A and IL-4. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 125, 222–230 e4 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.012 (doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu J, et al. 2009. Down-regulation of Gfi-1 expression by TGF-β is important for differentiation of Th17 and CD103+ inducible regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 206, 329–341 10.1084/jem.20081666 (doi:10.1084/jem.20081666) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang YH, Voo KS, Liu B, Chen CY, Uygungil B, Spoede W, Bernstein JA, Huston DP, Liu YJ. 2010. A novel subset of CD4+ TH2 memory/effector cells that produce inflammatory IL-17 cytokine and promote the exacerbation of chronic allergic asthma. J. Exp. Med. 207, 2479–2491 10.1084/jem.20101376 (doi:10.1084/jem.20101376) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu J, et al. 2004. Conditional deletion of Gata3 shows its essential function in TH1–TH2 responses. Nat. Immunol. 5, 1157–1165 10.1038/ni1128 (doi:10.1038/ni1128) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Usui T, Preiss JC, Kanno Y, Yao ZJ, Bream JH, O'Shea JJ, Strober W. 2006. T-bet regulates Th1 responses through essential effects on GATA-3 function rather than on IFNG gene acetylation and transcription. J. Exp. Med. 203, 755–766 10.1084/jem.20052165 (doi:10.1084/jem.20052165) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grogan JL, Mohrs M, Harmon B, Lacy DA, Sedat JW, Locksley RM. 2001. Early transcription and silencing of cytokine genes underlie polarization of T helper cell subsets. Immunity 14, 205–215 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00103-0 (doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00103-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Szabo SJ, Dighe AS, Gubler U, Murphy KM. 1997. Regulation of the interleukin (IL)-12R beta 2 subunit expression in developing T helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 cells. J. Exp. Med. 185, 817–824 10.1084/jem.185.5.817 (doi:10.1084/jem.185.5.817) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smits HH, van Rietschoten JG, Hilkens CM, Sayilir R, Stiekema F, Kapsenberg ML, Wierenga EA. 2001. IL-12-induced reversal of human Th2 cells is accompanied by full restoration of IL-12 responsiveness and loss of GATA-3 expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 31, 1055–1065 (doi:10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1055::AID-IMMU1055>3.0.CO;2-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krawczyk CM, Shen H, Pearce EJ. 2007. Functional plasticity in memory T helper cell responses. J. Immunol. 178, 4080–4088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lohning M, Hegazy AN, Pinschewer DD, Busse D, Lang KS, Hofer T, Radbruch A, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. 2008. Long-lived virus-reactive memory T cells generated from purified cytokine-secreting T helper type 1 and type 2 effectors. J. Exp. Med. 205, 53–61 10.1084/jem.20071855 (doi:10.1084/jem.20071855) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hegazy AN, et al. 2010. Interferons direct Th2 cell reprogramming to generate a stable GATA-3+T-bet+ cell subset with combined Th2 and Th1 cell functions. Immunity 32, 116–128 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.004 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Veldhoen M, Uyttenhove C, van Snick J, Helmby H, Westendorf A, Buer J, Martin B, Wilhelm C, Stockinger B. 2008. Transforming growth factor-beta ‘reprograms’ the differentiation of T helper 2 cells and promotes an interleukin 9-producing subset. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1341–1346 10.1038/ni.1659 (doi:10.1038/ni.1659) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dardalhon V, et al. 2008. IL-4 inhibits TGF-β-induced Foxp3+ T cells and, together with TGF-β, generates IL-9+ IL-10+ Foxp3(-) effector T cells. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1347–1355 10.1038/ni.1677 (doi:10.1038/ni.1677) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lohoff M, et al. 2002. Dysregulated T helper cell differentiation in the absence of interferon regulatory factor 4. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 11 808–11 812 10.1073/pnas.182425099 (doi:10.1073/pnas.182425099) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goswami R, Jabeen R, Yagi R, Pham D, Zhu J, Goenka S, Kaplan MH. 2012. STAT6-dependent regulation of Th9 development. J. Immunol. 188, 968–975 10.4049/jimmunol.1102840 (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1102840) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ganeshan K, Bryce PJ. 2012. Regulatory T cells enhance mast cell production of IL-6 via surface-bound TGF-beta. J. Immunol. 188, 594–603 10.4049/jimmunol.1102389 (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1102389) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koenen HJ, Smeets RL, Vink PM, van Rijssen E, Boots AM, Joosten I. 2008. Human CD25highFoxp3pos regulatory T cells differentiate into IL-17-producing cells. Blood 112, 2340–2352 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133967 (doi:10.1182/blood-2008-01-133967) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xing J, Wu Y, Ni B. 2011. Th9: a new player in asthma pathogenesis? J. Asthma 48, 115–125 10.3109/02770903.2011.554944 (doi:10.3109/02770903.2011.554944) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jager A, Dardalhon V, Sobel RA, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. 2009. Th1, Th17, and Th9 effector cells induce experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with different pathological phenotypes. J. Immunol. 183, 7169–7177 10.4049/jimmunol.0901906 (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0901906) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Staudt V, et al. 2010. Interferon-regulatory factor 4 is essential for the developmental program of T helper 9 cells. Immunity 33, 192–202 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.014 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tan C, Gery I. 2012. The unique features of Th9 cells and their products. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 32, 1–10 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v32.i1.10 (doi:10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v32.i1.10) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Locksley RM. 2009. Nine lives: plasticity among T helper cell subsets. J. Exp. Med. 206, 1643–1646 10.1084/jem.20091442 (doi:10.1084/jem.20091442) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eller K, Wolf D, Huber JM, Metz M, Mayer G, McKenzie AN, Maurer M, Rosenkranz AR, Wolf AM. 2011. IL-9 production by regulatory T cells recruits mast cells that are essential for regulatory T cell-induced immune suppression. J. Immunol. 186, 83–91 10.4049/jimmunol.1001183 (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1001183) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rubtsov YP, Niec RE, Josefowicz S, Li L, Darce J, Mathis D, Benoist C, Rudensky AY. 2010. Stability of the regulatory T cell lineage in vivo. Science 329, 1667–1671 10.1126/science.1191996 (doi:10.1126/science.1191996) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Komatsu N, Mariotti-Ferrandiz ME, Wang Y, Malissen B, Waldmann H, Hori S. 2009. Heterogeneity of natural Foxp3+ T cells: a committed regulatory T-cell lineage and an uncommitted minor population retaining plasticity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 1903–1908 10.1073/pnas.0811556106 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0811556106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bailey-Bucktrout SL, Bluestone JA. 2011. Regulatory T cells: stability revisited. Trends Immunol. 32, 301–306 10.1016/j.it.2011.04.002 (doi:10.1016/j.it.2011.04.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miyao T, Floess S, Setoguchi R, Luche H, Fehling HJ, Waldmann H, Huehn J, Hori S. 2012. Plasticity of Foxp3+ T cells reflects promiscuous Foxp3 expression in conventional T cells but not reprogramming of regulatory T cells. Immunity 36, 262–275 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.012 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou X, Bailey-Bucktrout S, Jeker LT, Bluestone JA. 2009. Plasticity of CD4+ FoxP3+ T cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 21, 281–285 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.007 (doi:10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Darce J, Rudra D, Li L, Nishio J, Cipolletta D, Rudensky AY, Mathis D, Benoist C. 2012. An N-terminal mutation of the Foxp3 transcription factor alleviates arthritis but exacerbates diabetes. Immunity 36, 731–741 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.007 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bettini ML, et al. 2012. Loss of epigenetic modification driven by the Foxp3 transcription factor leads to regulatory T cell insufficiency. Immunity 36, 717–730 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.020 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koch MA, Tucker-Heard G, Perdue NR, Killebrew JR, Urdahl KB, Campbell DJ. 2009. The transcription factor T-bet controls regulatory T cell homeostasis and function during type 1 inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 10, 595–602 10.1038/ni.1731 (doi:10.1038/ni.1731) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koenecke C, et al. 2012. IFN-gamma production by allogeneic Foxp3+ regulatory T cells is essential for preventing experimental graft-versus-host disease. J. Immunol. 189, 2890–2896 10.4049/jimmunol.1200413 (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1200413) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Koch MA, Thomas KR, Perdue NR, Smigiel KS, Srivastava S, Campbell DJ. 2012. T-bet+ Treg cells undergo abortive Th1 cell differentiation due to impaired expression of IL-12 receptor beta2. Immunity 37, 501–510 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.031 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.031) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. 2003. Toll pathway-dependent blockade of CD4+CD25+ T cell-mediated suppression by dendritic cells. Science 299, 1033–1036 10.1126/science.1078231 (doi:10.1126/science.1078231) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zheng Y, et al. 2009. Regulatory T-cell suppressor program co-opts transcription factor IRF4 to control TH2 responses. Nature 458, 351–356 10.1038/nature07674 (doi:10.1038/nature07674) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Soroosh P, Doherty TA. 2009. Th9 and allergic disease. Immunology 127, 450–458 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03114.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03114.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chaudhry A, Rudra D, Treuting P, Samstein RM, Liang Y, Kas A, Rudensky AY. 2009. CD4+ regulatory T cells control TH17 responses in a Stat3-dependent manner. Science 326, 986–991 10.1126/science.1172702 (doi:10.1126/science.1172702) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pallandre JR, et al. 2007. Role of STAT3 in CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory lymphocyte generation: implications in graft-versus-host disease and antitumor immunity. J. Immunol. 179, 7593–7604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Linterman MA, et al. 2011. Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nat. Med. 17, 975–982 10.1038/nm.2425 (doi:10.1038/nm.2425) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chung Y, et al. 2011. Follicular regulatory T cells expressing Foxp3 and Bcl-6 suppress germinal center reactions. Nat. Med. 17, 983–988 10.1038/nm.2426 (doi:10.1038/nm.2426) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cipolletta D, Feuerer M, Li A, Kamei N, Lee J, Shoelson SE, Benoist C, Mathis D. 2012. PPAR-gamma is a major driver of the accumulation and phenotype of adipose tissue Treg cells. Nature 486, 549–553 10.1038/nature11132 (doi:10.1038/nature11132) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hansmann L, Schmidl C, Kett J, Steger L, Andreesen R, Hoffmann P, Rehli M, Edinger M. 2012. Dominant Th2 differentiation of human regulatory T cells upon loss of FOXP3 expression. J. Immunol. 188, 1275–1282 10.4049/jimmunol.1102288 (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1102288) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang Y, Su MA, Wan YY. 2011. An essential role of the transcription factor GATA-3 for the function of regulatory T cells. Immunity 35, 337–348 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.012 (doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wohlfert EA, et al. 2011. GATA3 controls Foxp3+ regulatory T cell fate during inflammation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4503–4515 10.1172/JCI57456 (doi:10.1172/JCI57456) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]