Abstract

Background. Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is transmitted by sand flies. Protection of needle-challenged vaccinated mice was abrogated in vector-initiated cutaneous leishmaniasis, highlighting the importance of developing natural transmission models for VL.

Methods. We used Lutzomyia longipalpis to transmit Leishmania infantum or Leishmania donovani to hamsters. Vector-initiated infections were monitored and compared with intracardiac infections. Body weights were recorded weekly. Organ parasite loads and parasite pick-up by flies were assessed in sick hamsters.

Results. Vector-transmitted L. infantum and L. donovani caused ≥5-fold increase in spleen weight compared with uninfected organs and had geometric mean parasite loads (GMPL) comparable to intracardiac inoculation of 107–108 parasites, although vector-initiated disease progression was slower and weight loss was greater. Only vector-initiated L. infantum infections caused cutaneous lesions at transmission and distal sites. Importantly, 45.6%, 50.0%, and 33.3% of sand flies feeding on ear, mouth, and testicular lesions, respectively, were parasite-positive. Successful transmission was associated with a high mean percent of metacyclics (66%–82%) rather than total GMPL (2.0 × 104–8.0 × 104) per midgut.

Conclusions. This model provides an improved platform to study initial immune events at the bite site, parasite tropism, and pathogenesis and to test drugs and vaccines against naturally acquired VL.

Keywords: visceral leishmaniasis, Leishmania, Lutzomyia longipalpis, sand fly, vector, transmission, bite, intracardiac

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a neglected vector-borne disease causing fever, fatigue, weight loss, anemia, and hepatosplenomegaly in humans. Untreated, VL is almost 100% fatal within 2 years [1]. VL is transmitted by phlebotomine sand flies and is caused by 2 species of Leishmania. Leishmania infantum (=Leishmania chagasi) is prevalent in the Mediterranean Basin and Latin America and has a zoonotic transmission cycle [1–4]. Leishmania donovani is prevalent in the Indian subcontinent, South Asia, and East Africa [1, 5] and is considered mostly anthroponotic [1, 2].

Most VL studies involve intravenous, intracardiac, or intraperitoneal injection of 106–108 parasites into laboratory animals [6–11]. These routes bypass the skin, an immunologically privileged tissue [12] and the natural delivery site of the parasites. Progressive VL in hamsters was also achieved via intradermal injection of 105 parasites, a route closer to natural transmission by sand fly bites [13, 14]. For cutaneous leishmaniasis, natural transmission by vector bites revealed important distinctions in disease initiation, progression, and response to vaccination compared with needle challenge [15–18]. This likely reflects the complexity of transmission by vector bites. Leishmania are delivered into skin together with molecules that modulate the bite site, including salivary proteins and parasite-derived promastigote secretory gel [19–21]. Additionally, an infected sand fly displays modified feeding behavior with prolonged and persistent probing [22]. All the above initiates a rapid influx of immune cells to the bite site, adding to the complexity of parasite delivery following transmission by bite [16]. The dose delivered by sand flies into skin may also be relevant to disease initiation and evolution [23]. Kimblin et al [24], reported that Phlebotomus duboscqi, a natural vector of L. major, transmits 10 to 105 parasites, whereas Phlebotomus perniciosus and Lutzomyia longipalpis, natural vectors of L. infantum, transmit 8 to 4 × 104 parasites and 4 to 104 parasites, respectively [25, 26]. Despite variability in the dose delivered by individual infected flies, it remains significantly lower compared with the inoculum commonly used in needle-injection models, with the majority of sand flies delivering fewer than 600 parasites [24–26].

Because it mimics clinicopathologic features of active human disease, the hamster needle-injection model of experimental VL has been extensively used for studies on disease pathogenesis and immunosuppression [27–30] and to test efficacy of drugs and vaccines [7–10, 30–32]. To date, there are no models of natural transmission by vector-bite for VL. Studies reporting successful transmission of Leishmania parasites by VL vectors [25, 26] address load delivered by bite without further demonstration of disease progression. We report development of reproducible progressive VL in hamsters following transmission of L. infantum and L. donovani by vector bite and describe disease features unique to sand fly transmission and relevant to naturally acquired VL.

METHODS

Animals and Parasites

Male 3- to 6-week-old Golden Syrian hamsters (Hsd Han TM-AURA strains) from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) were used. Animals were housed under pathogen-free conditions at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Twinbrook animal facility in Rockville, Maryland. All animal experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the NIAID Animal Care and Use Committee.

Parasite strains used include 2 recent isolates of L. infantum (MCAN/BR/09/52, MCAN/IT/11/10545) from dogs with advanced canine leishmaniasis from the endemic areas of Natal, Brazil, and Naples, Italy, respectively, and established strains L. infantum (MHOM/BR/00/1669) and L. donovani (MHOM/SD/62/1S). Parasites were maintained in Golden Syrian hamsters. Promastigotes were cultured in Schneider's medium (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l–glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μL/mL streptomycin (complete Schneider's) at 26°C.

Sand Fly Infections

Colony-bred 2- to 4-day-old L. longipalpis females were infected by artificial feeding on defibrinated rabbit blood (Spring Valley Laboratories, Sykesville, MD) containing 5 × 106 amastigotes or first-passage promastigotes and 30 µL penicillin/streptomycin (10 000 units penicillin/10 mg streptomycin) per mL of blood for 3 hours in the dark as described elsewhere [15]. Fully blood-fed flies were separated and maintained at 26°C with 75% humidity and were provided 30% sucrose.

Pretransmission Scoring

L. infantum- and L. donovani-infected sand flies were scored at days 8 and 11, respectively, to assess pretransmission infection status. Flies (7–13) were washed, and each midgut was macerated with a pestle (Kimble Chase, Vineland, NJ) in an Eppendorf tube containing 50 µL of PBS. Parasite loads and percentage of metacyclics per midgut were determined using hemocytometer counts. Metacyclics were distinguished by morphology and motility.

Transmission of Leishmania to Hamsters via Sand Fly Bites

Hamsters were anesthetized intraperitoneally with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Ointment was applied to the eyes to prevent corneal dryness. Flies (20–30) with mature infections were applied to both ears of each hamster through a meshed surface of vials held in place by custom-made clamps. The flies were allowed to feed for 1–2 hours in the dark. Hamsters were monitored daily for appearance, activity, swelling, pain, and ulceration during the course of infection, and their body weights were recorded weekly. The end point for this study was reached when hamsters exhibited any of the following criteria: a 20% weight loss; inability to eat or drink; or becoming nonresponsive to external stimuli.

Posttransmission Scoring

The number of blood-fed flies was determined posttransmission. Where the infection status was established, all blood-fed flies were dissected and examined. Flies were assigned a “transmissible infection” status when a mature infection contained numerous active metacyclic promastigotes.

Infection of Hamsters by Intracardiac Injection

Hamsters were infected by intracardiac injection with 108 amastigotes of L. infantum (MHOM/BR/00/1669) or 107 stationary-phase promastigotes of L. donovani (MHOM/SD/62/1S). Hamsters were monitored as described above.

Transmissibility From Sick Hamsters to Sand Flies

Prior to euthanasia, sick hamsters were exposed to 10 uninfected sand flies per site for 1 hour in the dark. For vector-initiated infections, sand flies were placed against hamster ears (the original site of transmission) and at any observed skin lesions. For intracardiac-injected hamsters, flies were placed against ears and unbroken (normal) abdominal skin. Two days after exposure, blood-fed flies were dissected and examined for presence of live Leishmania parasites.

Processing of Hamsters

Hamsters were euthanized by intraperitoneal anesthesia with a mixture of 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine followed by CO2 inhalation. The spleen and liver from each hamster were removed aseptically and weighed. Impression smears from spleen, liver, and skin lesions were stained with Diff-Quick (Astral Diagnostics, Paulsboro, NJ) and examined for parasites. Aspirates from mouth, paw, and testicular lesions were cultured in complete Schneider's medium for 2 weeks at 26°C and examined for growth of Leishmania parasites.

Parasite Load

Parasite load was quantified by limiting dilution assay as described elsewhere [33, 34]. Briefly, whole organs were macerated aseptically through 70-μm cell strainers in 5–20 mL complete Schneider's medium. Homogenates (50–200 µL) were diluted serially (1:4 or 1:5) in 96-well plates containing biphasic medium prepared using 50 µL NNN medium with 10% defibrinated rabbit blood overlaid with complete Schneider's. Parasite load was determined from the highest dilution at which Leishmania promastigotes could be grown after 15 days of incubation at 26°C. Parasite loads exceeding 1015 are considered approximate.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the unpaired two-tailed Student t test or 2-tailed Mann-Whitney test using 4.0 Prism Software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). P values < .05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

L. infantum Infection Parameters in Lu Longipalpis Sand Flies

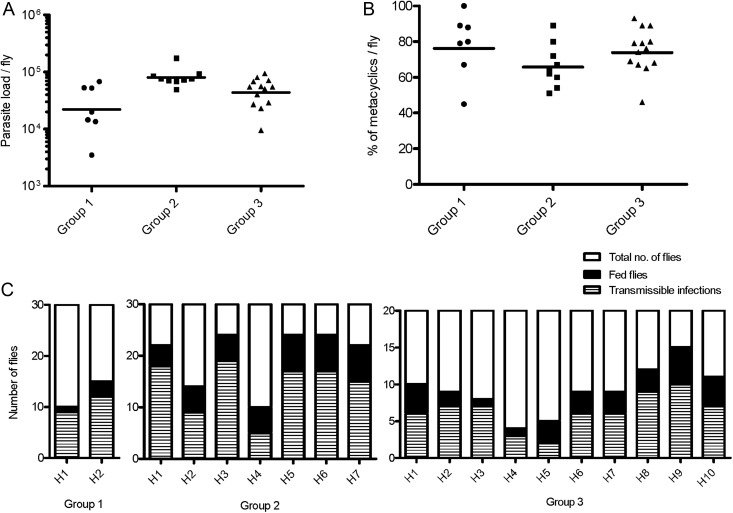

For sand fly groups infected with L. infantum (MCAN/BR/09/52), 7, 9, and 13 flies were examined to determine the geometric mean parasite load (GMPL) per midgut prior to transmission (Figure 1A). GMPL was 2 × 104, 8 × 104, and 4 × 104 for groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively (Figure 1A). Importantly, the mean percent of metacyclics per midgut ranged from 66% to 76% (Figure 1B). Blood-feeding and infection statuses of flies that took a blood meal (fed flies) were evaluated immediately following exposure. In 3 independent experiments, the average percent of fed flies was 42%, 67%, and 46% for groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Notably, within these fed-fly groups, the percent that harbored transmissible infections was high at an overall average of 85% (range, 80%–90%), 69% (50%–82%), and 68% (40%–88%) in group 1, 2, and 3, respectively (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Pre- and posttransmission status of Lutzomyia longipalpis sand flies infected with Leishmania infantum. (A) Total number of promastigotes per fly prior to transmission. Bars represent the geometric means. (B) Percent metacyclic promastigotes per fly. The parasite load and percent metacyclics per fly were assessed 8 days after sand fly infections. (C) Post transmission feeding score (black bars) and infection status of fed flies (striped bars) from 20–30 total sand flies (white bars) exposed to both ears of each hamster (H represents an individual hamster). Data from 3 independent experiments (groups 1–3) are shown.

Similar infection parameters were observed in flies infected with another strain of L. infantum (MCAN/IT/11/10545) from Italy (Supplementary data and Supplementary Figure 1A).

Clinicopathology of Progressive VL in Hamsters Following Bites of L. infantum-infected Lu. longipalpis Sand Flies

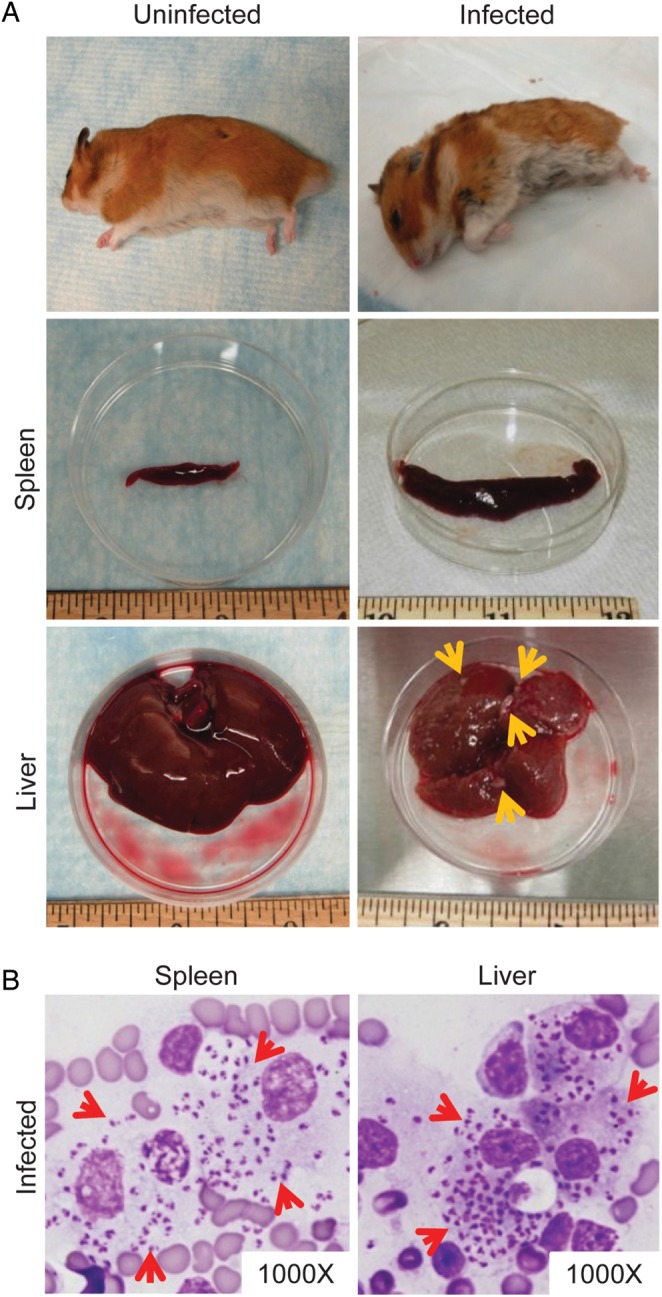

Following vector transmission with 20–30 flies, hamsters were followed for a maximum of 9 months or were euthanized upon reaching the study endpoint. All hamsters acquired visceralizing infections following transmission with L. infantum (MCAN/BR/09/52). Most hamsters (17 of 19; 89.5%) reached the study endpoint 4–9 months posttransmission and exhibited severe splenomegaly; the remaining 2 animals did not show external signs of disease but had moderate splenomegaly upon examination. Of the 19 infected hamsters, 73.7% presented an aggravated weight loss accompanied by dehydration and a hunched posture (Figure 2A); none developed ascites. The liver in the 17 hamsters was fibrotic, containing slightly raised white foci, and changed color from red to pale yellowish-brown (Figure 2A). Numerous L. infantum amastigotes were observed in smears from spleen and liver tissue of all hamsters (Figure 2B). Hamsters infected via vector bites with L. infantum (MCAN/IT/11/10545) showed similar clinical symptoms (Supplementary data and Supplementary Figure 1C and D).

Figure 2.

Clinicopathologic features of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) in hamsters following a vector-initiated infection with Leishmania infantum. (A) Macroscopic features of VL in a representative sick hamster (infected) compared with a healthy animal (uninfected). The infected hamster is hunched, scruffy, and thin, exhibiting dramatic weight loss (top row). The infected spleen (middle row) is enlarged, and the liver (bottom row) is fibrotic, containing multiple raised white foci (yellow arrows). The liver tissue also changes color from dark red to a brownish hue. (B) Heavy parasite burden in visceral organs of a representative infected hamster. Tissue impression smear of the spleen and liver stained with Diff-Quick shows macrophages heavily infected with L. infantum amastigotes (red arrows).

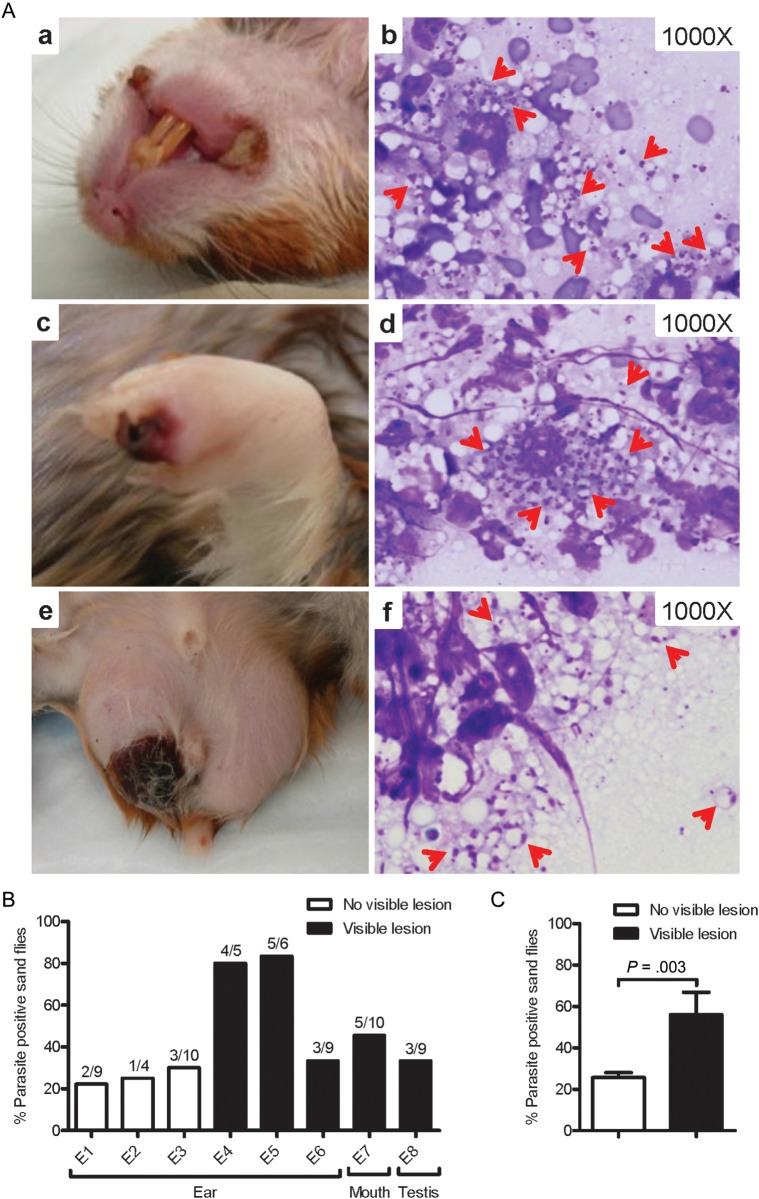

Interestingly, 21% of infected hamsters developed large scabs/sores on both corners of their mouth, 10.5% displayed red swollen paws with scabby lesions, and 15.8% had swollen testicles with large scabby wounds (Figure 3A, a, c, and e). Amastigotes were observed in tissue smears (Figure 3A, b, d, and f), and live parasites were cultured from samples from these lesions. Skin involvement was also observed in hamsters following vector-transmission of L. infantum (MCAN/IT/11/10545) (Supplementary data).

Figure 3.

Skin lesions and parasite transmissibility to sand flies in sick hamsters infected via vector-transmission of Leishmania infantum. (A) Large scabs/sores on both corners of the mouth (a), paw (c), and testis (e) from a representative infected hamster. Diff-Quick stained skin smears from mouth (b), paw (d), and testis (f) lesions showing L. infantum amastigotes (red arrows). (B) Transmissibility to sand flies from ears (original site of vector-transmission) and distal mouth and testis lesions 6–9 months following infection. Data from 8 independent exposures (E1–E8) are shown. (C) Overall success of parasite pick-up following exposure to sites with or without visible lesions. Black bars represent sites with skin lesions where sand flies were placed; white bars represent sites with no visible lesions. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Infectivity of skin lesions of sick hamsters to sand flies was evaluated immediately before euthanasia. The overall efficiency of parasite pick-up from the original site of transmission in ears was 45.6% (Figure 3B). This decreased to 25.7% in the absence of a lesion and increased to 65.5% when there were visible lesions. Additionally, sand flies efficiently picked up parasites from skin lesions distal to the site of bites, where 50% and 33.3% of flies fed on mouth and testicular lesions, respectively, were positive (Figure 3B). As predicted, overall success of parasite pick-up was significantly higher in the presence of lesions (Figure 3C; P = .003). Notably, when we exposed 50 uninfected flies to sick hamsters that had reached the endpoint following intracardiac injection, none of the fed flies picked up parasites (data not shown).

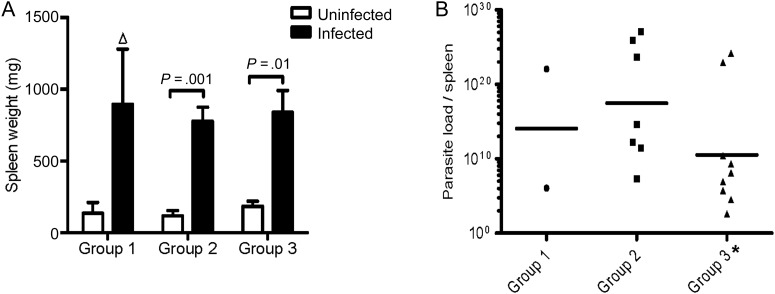

Reproducibility of Progressive VL Following Transmission of L. infantum by Bite

All 19 hamsters exposed to infected sand flies (SFi-exposed) from 3 independent experiments showed enlarged spleens whose mean weight ranged from 5- to 7-fold above that of uninfected hamster spleens (Figure 4A). There was no difference in liver weights between naive and infected hamsters (data not shown). GMPL per spleen for all SFi-exposed hamsters (excluding one that expired before euthanasia) was 4.0 × 1013 (Figure 4B). Significantly, spleen weight and GMPL per spleen were comparable between the 3 independently SFi-exposed groups. Similar results were obtained following vector-transmission of VL using L. infantum (MCAN/IT/11/10545) parasites from Italy (Supplementary data and Supplementary Figure 1E and F).

Figure 4.

Reproducibility of vector-initiated infections with Leishmania infantum in hamsters. (A) Spleen weight of infected sand fly (SFi)-exposed (black bars) and uninfected (white bars) hamsters. Error bars represent mean ± SEM Δ, Statistics not provided due to low number of animals. (B) Geometric mean parasite load per spleen for SFi-exposed hamsters. A total of 2, 7, and 10 hamsters were used in groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively. *One hamster from group 3 expired and was not processed. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

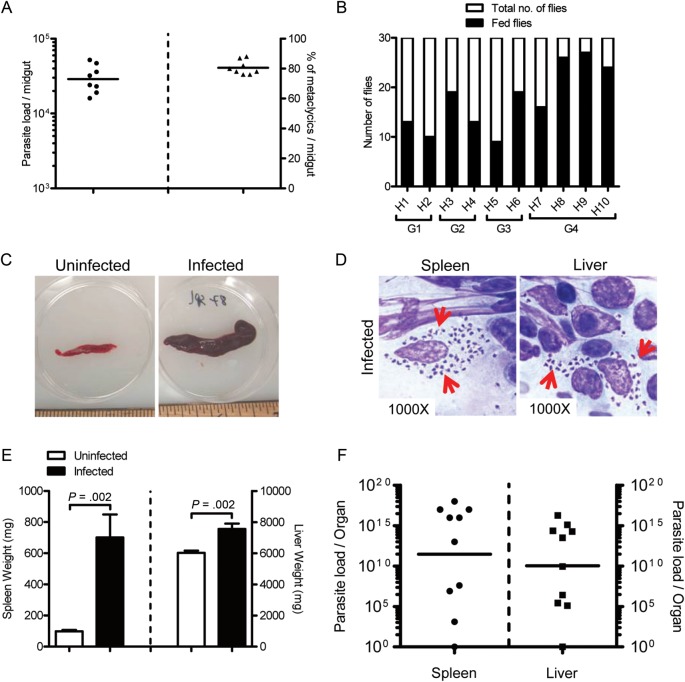

Progressive VL Following Vector Transmission With L. donovani

We also investigated the outcome of VL following vector-transmission of L. donovani (MHOM/SD/62/1S). Figure 5A shows pretransmission GMPL (2.9 × 104) and mean percent of metacyclics (80.5%) for a representative group of flies used to transmit L. donovani to hamsters (Figure 5A). The mean number of flies fed per hamster was 18 of a total of 30 (Figure 5B). Ten SFi-exposed hamsters from 4 independent experiments were followed for 9 months posttransmission. Nine of the 10 SFi-exposed hamsters developed splenohepatomegaly, which was severe in 6 of the 9 animals. Figure 5C shows a representative spleen from a sick hamster compared with one from an uninfected animal. Numerous L. donovani amastigotes were observed in impression smears from spleen and liver (Figure 5D). Contrary to vector-initiated infections with L. infantum, a significant increase was observed in the weight of infected livers of L. donovani SFi-exposed hamsters (P = .002; Figure 5E). GMPL per organ in SFi-exposed hamsters was 2.8 × 1011 for the spleen and 1.1 × 1010 for the liver (Figure 5F). Notably, one hamster remained uninfected throughout the experiment, probably due to poor transmission. Cutaneous involvement was not noted in any L. donovani-infected hamsters following vector transmission.

Figure 5.

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) in hamsters following a vector-initiated infection with Leishmania donovani. (A and B) Parameters of infected sand flies used for transmission. (A) Pretransmission status in a representative group of L. donovani-infected Lutzomyia longipalpis sand flies. Parasite load (circles) and percent metacyclics per fly (triangles) 10 days post sand fly infection are shown. Lines represent geometric means. (B) Posttransmission feeding score (black bars) of 30 infected flies (white bar) exposed to both ears of 10 hamsters (H1–H10) from 4 independent experiments (G1–G4). (C) Spleen from an uninfected (left) and a representative infected (right) hamster. (D) Tissue impression smear stained with Diff-Quick from the spleen (left) and liver (right) of a representative infected hamster showing numerous amastigotes within parasitized macrophages (red arrows). (E and F) Cumulative data of 4 independent experiments are shown. (E) Spleen (left bars) and liver weights (right bars) of infected sandy fly (SFi)-exposed (black bars) hamsters compared with a group of 8 uninfected (white bars) hamsters. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. (F) Parasite load per organ for the spleen (circles) and liver (squares) in SFi-exposed hamsters determined by limiting dilution assay. Bars represent the geometric means. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

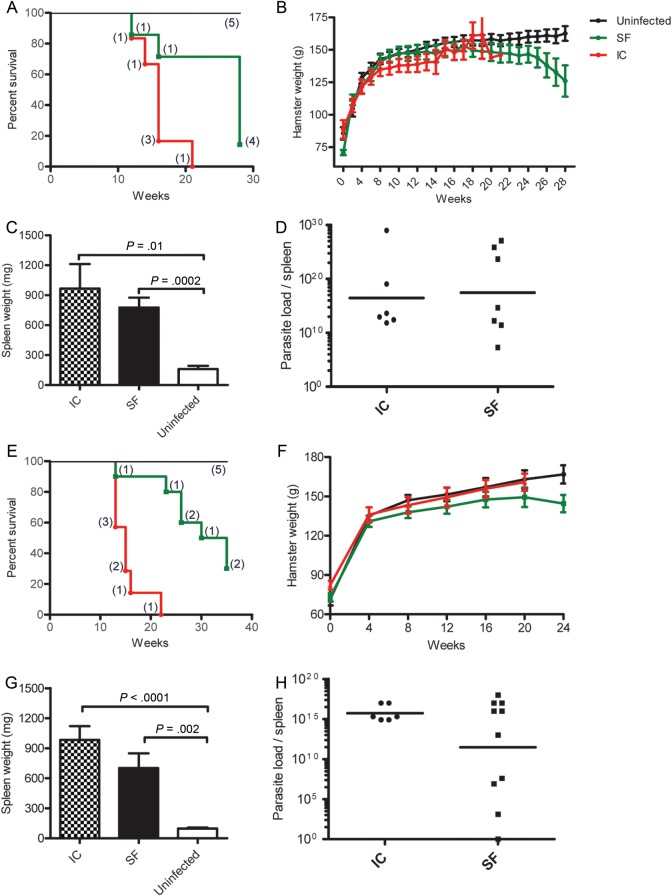

Comparison of Vector Transmission and Intracardiac-injection Models

Progression of VL following vector transmission to hamsters via bites of L. longipalpis infected with either L. infantum (MCAN/BR/09/52) or L. donovani (MHOM/SD/62/1S) were compared with those of hamsters injected intracardiacally with either 108 L. infantum (MHOM/BR/00/1669) amastigotes freshly isolated from a hamster spleen or 107 stationary-phase L. donovani (MHOM/SD/62/1S) promastigotes. Survival of 7 hamsters following vector transmission of L. infantum (group 2; Figures 1 and 4) was compared with that of 5 uninfected and 6 intracardiac-infected hamsters (Figure 6A). All 6 intracardiac -infected and 6 of 7 SFi-exposed hamsters reached the study endpoint and were euthanized (Figure 6A). Despite comparable mortality in hamsters infected by the 2 inoculation methods, SFi-exposed hamsters succumbed more slowly to disease compared with intracardiac-infected hamsters (Figure 6A). Furthermore, SFi-exposed hamsters did not develop ascites and showed progressive weight loss beginning at 18 weeks postinfection (Figure 6B). This is distinct from intracardiac-infected hamsters, in which production of ascites masked the weight loss of the animals (Figure 6B). Importantly, the spleen weight and parasite load per spleen were comparable in SFi-exposed and intracardiac-infected hamsters (Figure 6C and D), showing that the virulence of vector-transmission parallels that of a direct injection of 108 L. infantum (MHOM/BR/00/1669) parasites into the heart. Similar findings were observed in hamsters following vector-transmission of L. donovani. Survival of the 10 SFi-exposed hamsters was compared with that of 5 uninfected and 7 intracardiac-infected hamsters (Figure 6E). All 7 intracardiac-infected hamsters reached the study endpoint and required euthanasia within 22 weeks postinfection (Figure 6E). In comparison, 70% of the 10 SFi-exposed hamsters reached the study endpoint 35 weeks postinfection (Figure 6E). In contrast to naive hamsters that gained weight steadily over time, SFi-exposed animals—except one—did not develop ascites and began to lose weight 5 months postinfection (Figure 6F). Notably, weight lost by intracardiac-infected hamsters was not evident, probably due to weight gained from ascites (Figure 6F). Despite the lower rate of mortality of SFi-exposed hamsters, the animals displayed an increase in spleen weight and a high parasite load per spleen comparable to that in intracardiac-infected hamsters (Figure 6G and H).

Figure 6.

Comparative clinicopathology of VL in hamsters infected by intracardiac injection or sand fly bites. (A–D) Hamsters infected via intracardiac injection with 108 Leishmania infantum (MHOM/BR/00/1669, Li) amastigotes were compared with animals exposed to 20–30 L. infantum (MCAN/BR/09/52)-infected sand fly (SFi) bites. (E–H) Hamsters were infected via intracardiac -injection with 107 Leishmania donovani (MHOM/SD/62/1S, Ld) amastigotes or through 30 (SFi) bites. (A and E) Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing representative groups of intracardiac -infected hamsters (red lines; n = 6, Li; n = 7, Ld) and SFi-exposed hamsters (green lines; n = 7, Li; n = 10, Ld) compared with a group of uninfected hamsters (black lines; n = 5 for each). (B and F) Body weight fluctuation over time in uninfected hamsters (black lines), intracardiac -infected hamsters (red lines), and SFi hamsters (green lines). (C and G) Spleen weight in intracardiac -infected (checkered bars) and SFi-exposed (black bars) groups compared with uninfected (white bars) hamsters. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. (D and H) Parasite load per spleen in intracardiac -infected (circles) and SFi-exposed (squares) hamsters. Splenic tissue was harvested at the endpoint, and parasite load was quantified by limiting dilution assay. Bars represent the geometric means. P < .05 is considered statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

A vector-challenge model for cutaneous leishmaniasis induced an immune response distinct from needle challenge [15–17]. Additionally, vector-initiated infections are significantly more virulent compared with needle injection of culture-generated parasites [16, 20]. This has several implications, most important being its influence on the outcome of infection following vaccination. Studies using L. major and Leishmania mexicana demonstrated that vaccination protected mice against needle challenge but failed against vector challenge [17, 35]. This clearly demonstrates that a vector-initiated infection is crucial for studies aimed at understanding pathogenesis, immunity, and vaccine evaluation for leishmaniasis. Early animal models for the study of VL necessitated inoculation of Golden Syrian hamsters with a large number of parasites via intracardiac or intraperitoneal routes to reproduce similar clinicopathologic features of human VL [6, 27]. This needle-injection model represents a valuable tool for the study of pathogenesis, immunosuppression, and response to drugs and vaccine candidates [7–10, 28–31]. Nevertheless, it differs from a natural infection initiated by sand fly bites and does not reflect the complexity of parasite delivery at the bite site. Establishing a model of vector-transmitted VL will provide the opportunity to address issues such as parasite tropism and characterization of early immune events at the bite site that precede—and may regulate—dissemination to internal organs. Furthermore, this model will permit a comparison of the immunopathogenesis of VL after vector and needle challenges.

We achieved effective transmission to hamsters using sand flies with a GMPL that varied from 22 000 to 80 000 for L. infantum (MCAN/BR/09/52) and was 29 000 for L. donovani. This broad range of midgut parasite loads is similar to those reported by others for L. longipalpis infected with L. infantum [25, 26]. Of note, both studies used these infected sand fly groups in successful transmissions. In particular, Secundino et al [26], demonstrated successful transmission in groups of flies with parasites loads <20 000. This suggests that a high midgut parasite load may not be a prerequisite for successful transmission of visceralizing strains of Leishmania. Instead, what was noteworthy in the sand fly groups used in successful transmissions in this study was their high mean percent of metacyclics of 66%–82%. This is substantially higher than has been reported for L. major-infected P. duboscqi sand flies, where the mean percent metacyclics was 30.7% for high-dose transmitters and 16.2% for the low-dose transmitters [24].

None of the studies of the parasite dose delivered by VL vectors addressed onset of disease or clinical manifestations of VL following natural transmission by infected sand fly bites. We present the first account to our knowledge of clinicopathologic features of a vector-transmitted model of VL. Vector-initiated infections successfully generated clinically patent VL comparable with traditional needle-injection models and resulted in a significant increase in weight and parasite load of affected organs and in fatal progressive disease; however, hamsters infected by sand fly bites presented a significant weight loss but did not develop ascites, a prominent feature of needle-initiated infections. Vector transmission also generated a slower progression of VL that better resembled the chronicity of the disease following natural transmission in the field. The slower progression of disease may be relevant to evolution of immunity to infection and to pathogenesis. In low-dose models, L. major infection generated different disease profiles compared with those seen in high-dose models. Generally, low-dose infections resulted in a silent phase of parasite growth and lower acute pathology but showed a higher parasite titer in the chronic phase [23, 24]. Therefore, the slow progression of vector-initiated VL may be more appropriate for studies of early immune events, parasite establishment, and screening of drugs and vaccines.

One significant observation pertaining to vector-initiated infections was the distinct difference in the dissemination pattern of L. infantum compared with L. donovani parasites that is not commonly observed with traditional needle-injection models. Beginning at 15 weeks postinfection, L. infantum manifested cutaneous lesions distal to the site of original transmission with relatively high frequency (42%). This feature mimics the evolution of cutaneous lesions observed in most dogs. Furthermore, humans manifest cutaneous lesions at the bite site following infection with dermotropic L. infantum. Of note, sick hamsters presenting with infected cutaneous areas with or without visible lesions represented a rich source of parasites for infection of sand flies, suggesting that this feature is an important epidemiologic aspect of L. infantum transmission in nature. In contrast, none of the hamsters infected with L. donovani by vector bites developed skin lesions, suggesting inherent differences in these parasites that appropriately reflect their natural epidemiology. Furthermore, the use of L. longipalpis—a permissive vector species [36]—to transmit both L. infantum and L. donovani indicates that vector components are likely not responsible for the observed differential tropism of the 2 parasite species.

Our model of vector-initiated VL is reproducible, as demonstrated by the success of multiple independent transmissions of 2 strains of L. infantum and of L. donovani. Use of virulent parasite strains was vital for generating reproducible progressive VL infections. Here we infected flies with recent field isolates of L. infantum obtained from sick dogs that were passaged only twice in culture or once in hamsters. In the case of L. donovani, transmissible sand fly infections were obtained only with parasites freshly isolated from hamster spleens and passaged only once in culture. We also established a stringent protocol for evaluation of vector parameters. Apart from pretransmission scoring of fly groups for infections containing a mean percent of metacyclics over 50%, we added posttransmission assessment of blood-fed flies. This permits elimination of animals where there is a reasonable suspicion that transmission may have failed (see Supplemental data, Supplementary Figure 1B). Therefore, we recommend posttransmission assessment of the infection status of blood-fed flies as an additional criterion to assess successful transmission. Overall, our results show that hamsters can be reproducibly infected with either L. infantum or L. donovani following vector-transmission where animals develop progressive VL within 9 months on the condition that they receive bites from sand flies harboring transmissible infections.

In conclusion, availability of a model of vector-initiated progressive VL provides the opportunity to address previously elusive issues pertaining to early events of parasite establishment in the host including conundrums of tissue tropism between different Leishmania species. Moreover, it provides an improved platform to test experimental drugs and potential vaccines using a model of naturally acquired leishmaniasis.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Elvin Morales and Anika T. Haque for their help with sand fly colonization. We acknowledge the assistance and advice of Dr Daniel R. Paré, Twinbrook 3 facility veterinarian, NIAID. We thank Drs Robert Gwadz and Thomas Wellems for continuous support, and Brenda Rae Marshall and Meredith Shaffer, DPSS, NIAID, for editing. We also thank Adila Lorena Morais from the Center for Zoonosis in Natal for her help in identifying VL dogs from Natal. We also extend our thanks to Dr Mary Wilson, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa, for supplying us with amastigotes of Leishmania infantum (MHOM/BR/00/1669).

Financial support. The study was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health and by the Intramural Research Program of the Office of Blood Research and Review, Center for Biologics Research and Review, US Food and Drug Administration. Because R. D., R. C. D., H. L. N., J. G. V., and S. K. are government employees and this is government work, the work is in the public domain in the United States. Notwithstanding any other agreements, the NIH reserves the right to provide the work to PubMed Central for display and use by the public, and PubMed Central may tag or modify the work consistent with its customary practices. You can establish rights outside of the U.S. subject to a government use license.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Control of the leishmaniasis: report of a meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on the Control of Leishmaniases. Geneva: WHO; TRS N°949 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bern C, Maguire JH, Alvar J. Complexities of assessing the disease burden attributable to leishmaniasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ready PD. Leishmaniasis emergence in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romero GA, Boelaert M. Control of visceral leishmaniasis in Latin America—a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamjoom MB, Ashford RW, Bates PA, et al. Leishmania donovani is the only cause of visceral leishmaniasis in East Africa; previous descriptions of L. infantum and "L. archibaldi" from this region are a consequence of convergent evolution in the isoenzyme data. Parasitology. 2004;129:399–409. doi: 10.1017/s0031182004005955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garg R, Dube A. Animal models for vaccine studies for visceral leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:439–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kushawaha PK, Gupta R, Sundar S, Sahasrabuddhe AA, Dube A. Elongation factor-2, a Th1 stimulatory protein of Leishmania donovani, generates strong IFN-γ and IL-12 response in cured Leishmania-infected patients/hamsters and protects hamsters against Leishmania challenge. J Immunol. 2011;187:6417–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prajapati VK, Awasthi K, Gautam S, et al. Targeted killing of Leishmania donovani in vivo and in vitro with amphotericin B attached to functionalized carbon nanotubes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:874–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selvapandiyan A, Dey R, Nylen S, Duncan R, Sacks D, Nakhasi HL. Intracellular replication-deficient Leishmania donovani induces long lasting protective immunity against visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 2009;183:1813–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samant M, Gupta R, Kumari S, et al. Immunization with the DNA-encoding N-terminal domain of proteophosphoglycan of Leishmania donovani generates Th1-type immunoprotective response against experimental visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 2009;183:470–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nieto A, Dominguez-Bernal G, Orden JA, De La Fuente R, Madrid-Elena N, Carrion J. Mechanisms of resistance and susceptibility to experimental visceral leishmaniasis: BALB/c mouse versus Syrian hamster model. Vet Res. 2011;42:39. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-42-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters N, Sacks D. Immune privilege in sites of chronic infection: Leishmania and regulatory T cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;213:159–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomes R, Teixeira C, Teixeira MJ, et al. Immunity to a salivary protein of a sand fly vector protects against the fatal outcome of visceral leishmaniasis in a hamster model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7845–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712153105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.da Silva RA, Tavares NM, Costa D, et al. DNA vaccination with KMP11 and Lutzomyia longipalpis salivary protein protects hamsters against visceral leishmaniasis. Acta Trop. 2011;120:185–90. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamhawi S, Belkaid Y, Modi G, Rowton E, Sacks D. Protection against cutaneous leishmaniasis resulting from bites of uninfected sand flies. Science. 2000;290:1351–4. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5495.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters NC, Egen JG, Secundino N, et al. In vivo imaging reveals an essential role for neutrophils in leishmaniasis transmitted by sand flies. Science. 2008;321:970–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1159194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters NC, Kimblin N, Secundino N, Kamhawi S, Lawyer P, Sacks DL. Vector transmission of Leishmania abrogates vaccine-induced protective immunity. PloS Pathog. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000484. e1000484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomes R, Teixeira C, Oliveira F, et al. KSAC, a defined Leishmania antigen, plus adjuvant protects against the virulence of L. major transmitted by its natural vector Phlebotomus duboscqi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ribeiro JM, Mans BJ, Arca B. An insight into the sialome of blood-feeding Nematocera. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;40:767–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers ME, Ilg T, Nikolaev AV, Ferguson MA, Bates PA. Transmission of cutaneous leishmaniasis by sand flies is enhanced by regurgitation of fPPG. Nature. 2004;430:463–7. doi: 10.1038/nature02675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bethony JM, Cole RN, Guo X, et al. Vaccines to combat the neglected tropical diseases. Immunol Rev. 2011;239:237–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00976.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers ME, Bates PA. Leishmania manipulation of sand fly feeding behavior results in enhanced transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e91. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belkaid Y, Mendez S, Lira R, Kadambi N, Milon G, Sacks D. A natural model of Leishmania major infection reveals a prolonged "silent" phase of parasite amplification in the skin before the onset of lesion formation and immunity. J Immunol. 2000;165:969–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimblin N, Peters N, Debrabant A, et al. Quantification of the infectious dose of Leishmania major transmitted to the skin by single sand flies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10125–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802331105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maia C, Seblova V, Sadlova J, Votypka J, Volf P. Experimental transmission of Leishmania infantum by two major vectors: a comparison between a viscerotropic and a dermotropic strain. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Secundino NF, de Freitas VC, Monteiro CC, Pires AC, David BA, Pimenta PF. The transmission of Leishmania infantum chagasi by the bite of the Lutzomyia longipalpis to two different vertebrates. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:20. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melby PC, Chandrasekar B, Zhao WG, Coe JE. The hamster as a model of human visceral leishmaniasis: progressive disease and impaired generation of nitric oxide in the face of a prominent Th1-like cytokine response. J Immunol. 2001;166:1912–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mookerjee A, Sen PC, Ghose AC. Immunosuppression in hamsters with progressive visceral leishmaniasis is associated with an impairment of protein kinase C activity in their lymphocytes that can be partially reversed by okadaic acid or anti-transforming growth factor β antibody. Infect Immun. 2003;71:2439–46. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2439-2446.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goto H, Lindoso JA. Immunity and immunosuppression in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:615–23. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000400020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osorio EY, Zhao W, Espitia C, et al. Progressive visceral leishmaniasis is driven by dominant parasite-induced STAT6 activation and STAT6-dependent host arginase 1 expression. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002417. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banerjee S, Ghosh J, Sen S, et al. Designing therapies against experimental visceral leishmaniasis by modulating the membrane fluidity of antigen-presenting cells. Infect Immun. 2009;77:2330–42. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00057-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selvapandiyan A, Dey R, Gannavaram S, et al. Immunity to visceral leishmaniasis using genetically defined live-attenuated parasites. J Trop Med. 2012;2012:631460. doi: 10.1155/2012/631460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Titus RG, Marchand M, Boon T, Louis JA. A limiting dilution assay for quantifying Leishmania major in tissues of infected mice. Parasite Immunol. 1985;7:545–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1985.tb00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belkaid Y, Kamhawi S, Modi G, et al. Development of a natural model of cutaneous leishmaniasis: powerful effects of vector saliva and saliva preexposure on the long-term outcome of Leishmania major infection in the mouse ear dermis. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1941–53. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.10.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rogers ME, Sizova OV, Ferguson MAJ, Nikolaev AV, Bates PA. Synthetic glycovaccine protects against the bite of Leishmania-infected sand flies. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:512–8. doi: 10.1086/505584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamhawi S. Phlebotomine sand flies and Leishmania parasites: friends or foes? Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:439–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.