Abstract

Background. Whether unique human immunodeficiency type 1 (HIV) genotypes occur in the genital tract is important for vaccine development and management of drug resistant viruses. Multiple cross-sectional studies suggest HIV is compartmentalized within the female genital tract. We hypothesize that bursts of HIV replication and/or proliferation of infected cells captured in cross-sectional analyses drive compartmentalization but over time genital-specific viral lineages do not form; rather viruses mix between genital tract and blood.

Methods. Eight women with ongoing HIV replication were studied during a period of 1.5 to 4.5 years. Multiple viral sequences were derived by single-genome amplification of the HIV C2-V5 region of env from genital secretions and blood plasma. Maximum likelihood phylogenies were evaluated for compartmentalization using 4 statistical tests.

Results. In cross-sectional analyses compartmentalization of genital from blood viruses was detected in three of eight women by all tests; this was associated with tissue specific clades containing multiple monotypic sequences. In longitudinal analysis, the tissues-specific clades did not persist to form viral lineages. Rather, across women, HIV lineages were comprised of both genital tract and blood sequences.

Conclusions. The observation of genital-specific HIV clades only in cross-sectional analysis and an absence of genital-specific lineages in longitudinal analyses suggest a dynamic interchange of HIV variants between the female genital tract and blood.

Keywords: HIV, female genital tract, compartmentalization, viral lineages, monotypic HIV, genetic distances, uterine cervix, phylogenetics

Whether human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the female genital tract constitutes a genetically distinct compartment from the blood remains an important question, with both clinical and biologic implications because of the role of the genital tract in mother-to-child and woman-to-man sexual HIV transmission. Therefore, determining if unique viruses develop and persist in the genital tract is important for HIV prophylaxis. Similarly, understanding HIV evolution in tissues that transmit the infection, including the female genital tract, is relevant to vaccine development because vaccine-induced immune responses should target these viral strains.

During acute infection, a single HIV genotype predominates in the blood of approximately 70% of individuals [1–5], with several viral variants detected in the remainder [6]. Because of the poor fidelity of the viral reverse transcriptase, HIV diversifies within the new host [7–9]. The variants within a subject form multiple genetically distinct clades with ongoing replication have time-ordered structure [8, 10, 11].

Factors hypothesized to promote compartmentalization of HIV between the blood and genital tract and potentially lead to tissue-specific clades and lineages include differences in CD4 or coreceptor expression [12–14], HIV-specific immune pressure [11, 14–19], and selective antiretroviral pressure due to poor penetration into the genital tissues [20, 21] and inflammation from trauma [22] or sexually transmitted infections [13–16, 23–25].

Examination of HIV sequences from the genital tract and blood of >100 women across 9 cross-sectional and 2 longitudinal studies [11, 13, 14, 16–19, 23, 26–29] observed compartmentalization of virus in more than half of these women. Longitudinal studies of HIV sequences [11, 16] have examined a relatively small number of women. One study of cloned sequences from 3 women reported increasing compartmentalization between genital and blood virus over time [11]. A second study used a heteroduplex tracking assay and identified distinct genital variants in one-third of 12 women's paired plasma and genital tract specimens [16].

Our previous cross-sectional analyses of genital tract and blood viral sequences derived by single genome amplification (SGA) observed subpopulations of identical sequences in the blood and/or genital tract of most women [28, 29]. Among individuals with active viral replication, the observation of closely related sequences suggested that compartmentalization was largely due to sampling of a dominant replicating virus, whereas in women with viral replication suppressed by antiretroviral therapy, we hypothesized that monotypic (identical) HIV DNA sequences were likely due to proliferation of cells containing proviruses, as we [28–30] and others [19, 31, 32] have previously reported. Compartmentalization of HIV in these individuals was due to the clades of monotypic or low-diversity sequences (<0.5% genetic distance), which suggested to us that cross-sectional sampling would not accurately capture the natural history of HIV evolution within specific tissues or its exchange between tissues.

Given the paucity of longitudinal studies of HIV in the genital tract, we evaluated females with ongoing viral replication in both the genital tract and blood. Multiple viral sequences were derived by SGA from genital and blood specimens collected at several time points to determine whether HIV evolves genital tract–specific lineages. We hypothesized that viruses that predominate in the genital tract at one point in time would not persist to form unique genital-specific lineages over time. Rather, over time genital viruses would comingle with blood variants.

METHODS

Study Design

Women with chronic HIV infection who were not receiving antiretroviral therapy had blood and genital specimens collected in an observational longitudinal study [28, 29]. Specimens were collected quarterly during the first year and at 6-month intervals over the subsequent 4 years, always during the luteal phase of their menstrual cycle [28, 29, 33]. To avoid contamination of vaginal specimens with HIV from semen of sexual partners, women agreed to abstain from sexual intercourse or use condoms within 48 hours of their study visits. Subjects were eligible for the current analysis if approximately equal numbers of viral templates were derived from the genital tract and blood by SGA.

Compartmentalization of viruses was evaluated within each subject. First, sequences from the plasma and cervix were compared at each time point using 4 statistical tests: Slatkin–Maddison [34], branch length (r) correlation coefficient, branch count (rb) correlation coefficient [35], and Hudson's nearest neighbor (Snn) [36]. Second, plasma and genital sequences were compared separately between study visits using the Slatkin–Maddison and Snn tests to evaluate time-ordered structure. Third, sequences across all time points were combined for each subject by tissue source to compare genital tract with blood sequences. Migration events, defined as sequence transitions between tissues, were assessed for each subject across visits [34, 37]. Lastly, because of the impact of monotypic sequences on statistical assessments of compartmentalization, identical sequences in the alignment were collapsed to a single representative sequence for each tissue across time, and compartmentalization was reassessed using the Slatkin–Maddison and Snn tests [34] (Supplementary Table 1) .

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted at the University of Washington and at the University of Rochester following procedures approved by both institutional review boards. All study participants provided written informed consent.

Evaluation of Sexually Transmitted Infections and Genital Tract Inflammation

Women's genital tracts were evaluated for bacterial vaginosis (BV), Neisseria gonorrhea, Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis, shedding of herpes simplex viruses and cytomegalovirus, and cervical inflammation, as previously described [38].

Specimen Processing and Quantification of HIV RNA

Blood plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated by density centrifugation and stored at −80°C as described [29]. Cervical secretions were wicked using 3 filter paper strips to collect approximately 24 μL of secretions preserved in 500 μL of guanidinium isothiocyanate lysis buffer [33]. Cervicovaginal lavage (CVL) was then performed with 10 mL of 1 × phosphate-buffered saline spiked with lithium chloride (1 mg/mL) to estimate the volume of vaginal secretions retrieved [39].

Nucleic acids were extracted from plasma (500 μL) and CVL (1 mL) and cervical secretions (250 μL) using a silica-based method. HIV RNA in CVL was reverse transcribed and quantified in a 1-step reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) real-time assay, as described [40]. The lithium concentration in CVL was used to calculate the HIV RNA load in vaginal secretions [39] (formula in legend of Table 1). HIV RNA in cervical secretions was quantified by limiting dilution PCR and the software program, “QUALITY” [49].

Table 1.

Virologic and Immunologic Parameters of Subjects

| Subject ID | Study Month | CD4 Lymphocytes/μL Blood | Plasma HIV RNA log10 Copies/mL | Genital Tract HIV RNA log10 Copies/mLa,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1c | 0 | 373 | 5.63 | 5.24a |

| 15 | 97 | 6.00 | 4.54a | |

| 19 | 80 | 4.81 | 4.73a | |

| 2d | 0 | 903e | 2.99 | 5.96b |

| 39 | 785 | 3.03 | 3.47a | |

| 3c | 0 | 599 | 3.55 | 5.21a |

| 24 | 362 | 4.64 | 4.54a | |

| 4c | 0 | 71 | 4.20 | 3.41a |

| 8 | 71e | 4.23 | 4.61a | |

| 25 | 167 | 4.75 | 4.24a | |

| 5d | 0 | 581 | 3.43 | 4.75b |

| 38 | 461 | 4.56 | 4.22b | |

| 53 | 558 | 4.74 | 2.98a | |

| 6c | 0 | 467 | 4.84 | 5.19b |

| 17 | 467e | 4.87 | 5.39b | |

| 7c | 0 | 397 | 5.51 | 5.23a |

| 17 | 239e | 5.51 | 2.37a | |

| 8c | 0 | 302 | 5.00 | 4.22a |

| 22 | 167 | 4.92 | 4.66a |

Abbreviation: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

a Genital viral loads were quantified using cervicovaginal lavage (CVL) of vagina and uterine cervix with 10 mL of saline spiked with lithium chloride (LiCL) at 1 mg/mL. The concentration of LiCL in CVL was used to correct for dilution of genital secretions using the formula Cx = [Li1]/([Li1][Li2]), where Cx is the correction factor, Li1 is the lithium concentration in the stock saline prior to the lavage, and Li2 is the concentration after the sample was collected [46].

b Genital viral loads were quantified from 24 µL of cervical secretions wicked into Sno-strip/TearFlo and stored in 500 µL of guanidinium isothiocyanate by limiting dilution polymerase chain reaction and QUALITY [49], a freely available program. Cervical viral loads ranged between 3.98–6.35 log10 and are presented in Table 1 when the value was 2 log10 greater than those of genital secretions from CVL.

c Subject had a history of antiretroviral therapy and took medication at time points between or preceding study visits when specimens were collected.

d Subject was naive to antiretroviral therapy.

e CD4 counts were not available from date of study visit; value is from nearest available date (ranging 3–17 months).

Derivation of HIV RNA Genomes by SGA

Extracted nucleic acids were reverse transcribed into complementary DNA using SuperScript III and diluted to a concentration of approximately 1 template per 3 PCRs before amplification of the C2-V5 region of HIV env [28, 29]. To determine if HIV DNA was present in the nucleic acid extracts from plasma and genital specimens, 3 extracts were pooled and amplified without reverse transcription [29].

Sequence Analysis and Phylogram Construction

Sequences were assembled and checked for read errors and hypermutation [30]. A maximum likelihood phylogram of all subjects’ sequences was constructed to assess cross-contamination between specimens using PhyML as implemented by DIVEIN, a publicly available program (http://indra.mullins.microbiol.washington.edu/DIVEIN/) [41, 42] and subjected to a BLAST search using ViroBLAST (http://indra.mullins.microbiol.washington.edu/viroblast/viroblast.php). Both subtree pruning and grafting and nearest neighbor interchange were used to generate each subject's trees and evaluate diversity and divergence using general time-reversible parameters with optimized equilibrium frequencies and 4 substitution rate categories. Sequences with 0% pairwise differences were confirmed in alignments as identical and defined as monotypic.

The topology of each subject's maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was reviewed. A clade was defined by a monophyletic group of sequences with a bootstrap value of >70% [43, 44]. Clades comprised only of genital tract or blood sequences were defined as tissue-specific clades. As has been similary done by others [8, 11], viral lineages were defined as a clade(s) with >90% bootstrap with sequences from multiple study visits.

Evaluation of N-linked Glycosolation Sites

Nucleotide alignments were reviewed for the presence or absence of potential N-linked glycosylation sites in MacClade (http://macclade.org/index.html) and further interrogated using the N-Glycosite program at Los Alamos National Laboratory site, (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/GLYCOSITE/glycosite.html).

Statistical Analyses

The compartmental structure of viral sequences from each subject was evaluated as described above by 2 tree-based and 2 distance-based statistical tests [29, 45]. Compartmentalization was defined as having all 4 tests indicate significant restriction in genetic flow. After applying a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, P values of <.008 were considered significant.

The frequency of monotypic sequences in plasma vs. genital tract specimens was assessed across women using generalized estimating equations. Potential N-linked glycosylation sites (pNLG) were compared between the genital tract and plasma of each subject at each study visit using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Migration events between the plasma and genital tract were evaluated using a t test. These tests were two-sided, and a P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

The gene sequences determined in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers JN856490–JN857008.

RESULTS

Clinical Evaluations

Among 54 HIV-infected participants in the parent study conducted in 2003–2008 [38], only 8 had HIV RNA detected in both the plasma and genital secretions at multiple study visits. Sequences were derived from all 8 subjects; 5 subjects contributed samples from 2 study visits, and 3 subjects contributed samples from 3 study visits. The average time between study visits was 9 months (range, 3–48) (Table 1). SGA yielded a median of 14 (range, 9–25) HIV RNA sequences from each tissue at each time point; with a total of 538 sequences analyzed across the 8 women (Supplementary Table 1). The PCR of nucleic acids from plasma and genital secretions performed without reverse transcription were all negative, suggesting that HIV DNA was uncommon. Each subject's sequences clustered together in the all-inclusive tree, revealing no cross-contamination between specimens (Supplementary Figure 1).

All 8 women had either a sexually transmitted infection, evidence of BV, or cervical inflammation at ≥1 study visits (Table 2). BV (14 of 19 [74%] visits) and cervicitis (8 of 19 [42%] visits) were prevalent across study visits. Chlamydia trachomatis (1 of 19 [5%] visits), T. vaginalis (1 of 19 [5%] visits), and herpes simplex virus DNA (2 of 19 [11%] visits) were rarely detected, and N. gonorrhea and cytomegalovirus DNA were not detected (0 of 19 visits).

Table 2.

HIV Compartmentalization by Study Visit and Genital Tract Perturbations

| Subject ID (study month) | Evidence of HIV Compartmentalization (No. of significant tests) | Genital Tract Infections, Perturbations, and Inflammation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (0) | No (0) | Absent: cervicitis, CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: BV | ||

| (15) | Yes (4) | Absenta: CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich |

| Present: BV, yeast | ||

| (19) | No (0) | Absent: BV, CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: cervicitis | ||

| 2 (0) | Yes (4) | Absent: BV, cervicitis, CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: None | ||

| (39) | No (0) | Absenta: CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: BV | ||

| 3 (0) | Yes (2) | Absent: CMV, HPV, HSV, GC, yeast |

| Present: BV, CT, cervicitis, Tric | ||

| (24) | Yes (4) | Absenta: cervicitis, CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: BV | ||

| 4 (0) | Yes (2) | Absent: BV, cervicitis, CMV, CT, HPV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: HSV | ||

| (8) | No (0) | Absent: CMV, HPV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: HSV, CT, BV, cervicitis | ||

| (25) | No (0) | Absent: cervicitis, CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: BV | ||

| 5 (0) | No (0) | Absent: CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich |

| Present: BV, cervicitis, yeast | ||

| (38) | Yes (1) | Absent: BV, cervicitis, CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: None | ||

| (53) | No (0) | Absent: BV, CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: cervicitis | ||

| 6 (0) | Yes (1) | Absent: CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: BV, cervicitis | ||

| (17) | No (0) | Absent: cervicitis, CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: BV | ||

| 7 (0) | No (0) | Absent: CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: BV, cervicitis | ||

| (17) | Yes (2) | Absent: CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: BV, cervicitis | ||

| 8 (0) | No (0) | Absent: cervicitis, CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: BV | ||

| (22) | Yes (1) | Absent: cervicitis, CMV, CT, HPV, HSV, GC, Trich, yeast |

| Present: BV |

Cervicitis was defined as white blood cells >30 per high-powered field.

Abbreviations: BV, bacterial vaginosis; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; GC, Neisseria gonorrhea; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HPV, human papilloma virus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; Trich, Trichomonas vaginalis; yeast, Candida sp.;.

a No data available for cervicitis at this time point.

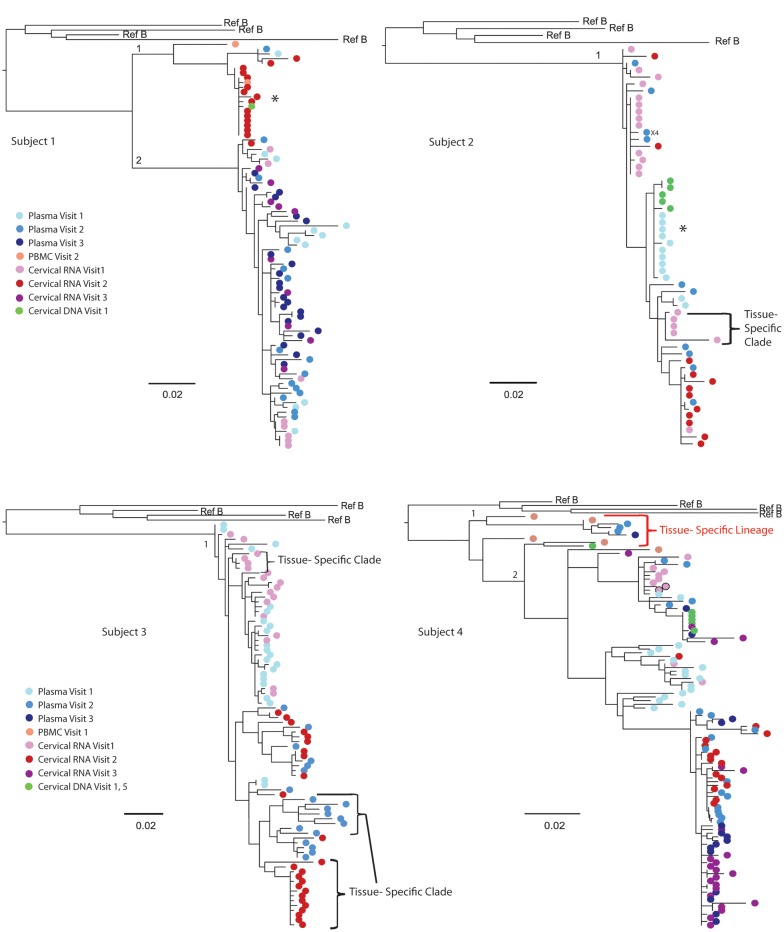

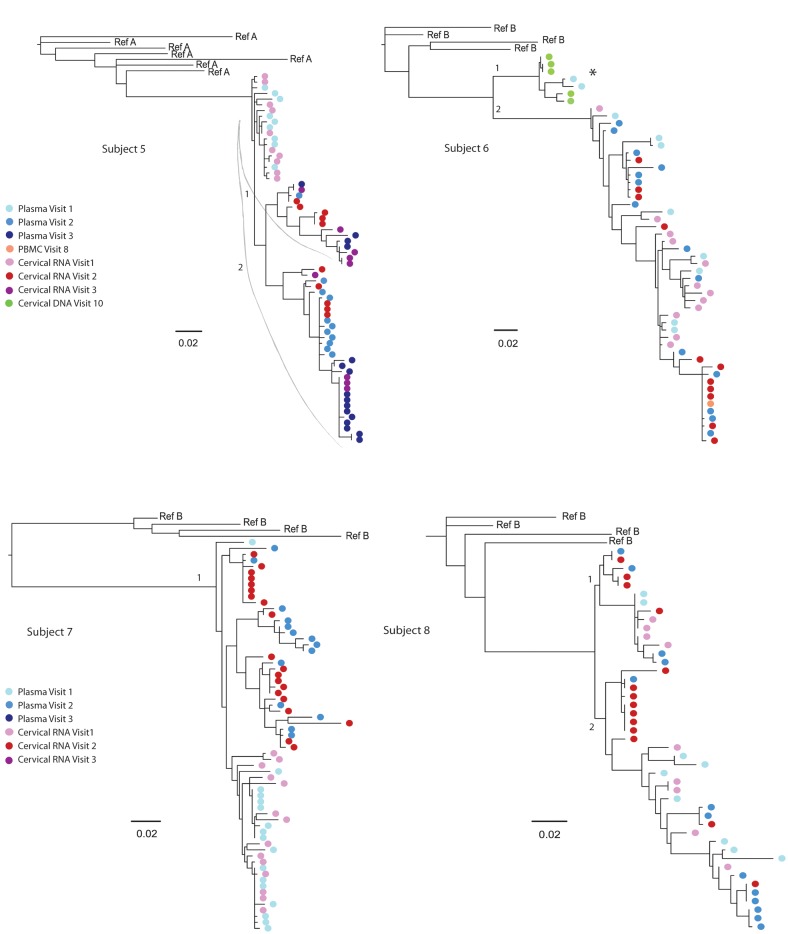

Cross-sectional Evaluation of HIV Compartmentalization

All subjects had compartmentalization of genital tract and blood sequences by at least 1 test at ≥1 study visits (9 of 19 [47%] visits), and 3 of 8 women had compartmentalization by all 4 tests at 3 of 19 (16%) study visits (Table 3, subjects 1–3). In the three subjects with compartmentalization by all 4 tests, viral sequences clustered in a unique tissue-specific clade with low genetic diversity (<0.005%), consisting primarily of monotypic sequences (Figure 1). Across women, monotypic sequences were proportionally greater in cervical secretions than in plasma (P = .049) (data not shown). Monotypic sequences occurred in women with less compartmentalization of HIV (Table 2 and Figure 1, subjects 4–8); however, their monotypic clades included both genital and blood sequences.

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic analyses of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) RNA env C2-V5 from longitudinal specimens collected from the genital tract and blood of female subjects. HIV sequences were derived by single-genome amplification of complementary DNA derived from plasma (visit 1, light blue color; visit 2, darker blue; visit 3, darkest blue) and uterine cervical secretions (visit 1, light pink color; visit, 2 red; visit 3, fuschia). Sequences derived from CVL are indicated by light pink with a black circle (subject 4) but yielded significantly fewer sequences. Cell-associated sequences from PBMCs; (orange) or from cervical biopsies (green) are included from other visits in subjects 1, 2, 4, and 6 to demonstrate the lack of tissue-specific lineages but were not included in the analysis of compartmentalization. Tissue-specific lineages were limited to one subject: Subject 4, with a tissue-specific lineage in the peripheral blood. Tissue-specific clades are identified by brackets for subjects 1, 2, and 6; an * indicates tissue-specific HIV RNA clades before the addition of cell-associated sequences. The sequence predicted to encode X4 tropic virus is indicated by “X4.” The scale bar (horizontal line) indicates the branch length corresponding to 2 substitutions per 100 base pairs. Tissue-specific HIV env clades were composed of monotypic or of low-diversity sequences and were observed in all 8 subjects but were more pronounced in subjects 1–3, who had significant compartmentalization. The addition of cell-associated sequences to subjects 1, 2, and 6 demonstrated these clades were not restricted to 1 tissue and did not persist over time to form a “lineage” [29]. Genetically divergent sequences (>8% genetic distance) were noted in 3 women (subjects 1, 4, and 6) and were considered to possibly be due to intravaginal semen containing HIV or superinfection or significant evolution over time. Given the duration of these women's HIV infection (diagnosed 8, 17, and 12 years prior) and that HIV DNA from cervical biopsies or PBMCs from other study visits grouped in these clades, the latter 2 seem more likely.

None of the clinical or genital parameters examined were associated with HIV compartmentalization. Sexually transmitted infections were prevalent in women with and without compartmentalization (Table 2). At the time points with significant compartmentalization by all 4 tests, 2 subjects had BV and/or yeast (subjects 1 and 3 at visit 2), but the third subject was negative for cervicitis, BV, and sexually transmitted infections (Table 2) [46]. Similarly, cervicitis and BV were observed in 5 of 8 women without marked compartmentalization.

Predicted HIV Coreceptor Usage and Potential N-Linked Glycosylation Sites

HIV env regions that encode predicted pNLG sites or coreceptor usage [46] or include deletions or insertions can distinctly segregate sequences in a phylogenetic tree. Only 1 subject in our study had a sequence predicted to use the CXCR4 coreceptor (Figure 1, subject 2). pNLG sites in env were more frequent (P < .05) in genital sequences than in the plasma sequences from 6 of 8 women (Supplementary Table 2, subjects 1–4, 6, and 7). However, exclusion of the pNLG sites from the sequences analyses did not change the clustering of monotypic or low-diversity virus clades, indicating that the pNLG sequence motifs did not cause the compartmentalization.

Evaluation of Genital-Specific HIV Lineages and Migration Events

Time-ordered clustering of sequences in both plasma (10 of 14 comparisons; P < .001) and genital tract (12 of 14; P < .001) was detected within each subject's plasma or genital tract sequences using Slatkin–Maddison and Snn tests (data not shown).

The within-subject across-visit analysis of compartmentalization between genital and blood sequences detected signal from the monotypic and low-diversity sequences previously noted in cross-sectional analyses (Table 3). When the monotypic sequences were collapsed in subjects 1 and 2, compartmentalization was no longer detected (Table 4). Because subject 3's tissue-specific clade was low diversity viruses rather than monotypic (Figure 1), it was not analyzed further.

Table 3.

Cross-sectional Analyses of Compartmentalization of HIV env Between Genital Tract Secretions vs Blood Plasma by Four Methodsa,b,c

| Subject ID | Study Month | Tests of Compartmentalization |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM | Snn | rb | r | ||

| 1 | 0 | .22 | .13 | .74 | .16 |

| 15 | <.001 | <.001 | .001 | .001 | |

| 19 | .37 | .03 | .52 | .24 | |

| 2 | 0 | <.001 | .001 | .007 | .002 |

| 39 | .05 | .04 | .02 | .02 | |

| 3 | 0 | .008 | .007 | .06 | .04 |

| 24 | .005 | <.001 | .005 | .004 | |

| 4 | 0 | .22 | .17 | .004 | .001 |

| 8 | .01 | .11 | .11 | .01 | |

| 25 | .78 | .29 | .44 | .15 | |

| 5 | 0 | .45 | .18 | .48 | .70 |

| 38 | .01 | .15 | .02 | .005 | |

| 53 | .82 | .61 | .06 | .20 | |

| 6 | 0 | .05 | .17 | .005 | .03 |

| 17 | .96 | .78 | .40 | .52 | |

| 7 | 0 | .50 | .21 | .13 | .91 |

| 17 | .04 | .13 | .001 | .002 | |

| 8 | 0 | .57 | .17 | .40 | .55 |

| 22 | .09 | .004 | .01 | .01 | |

a Tests: Slatkin–Maddison (SM) [34]; Hudson nearest neighbor (Snn) [36]; branch count correlation coefficient (rb); branch length (r) correlation coefficient [35].

b P ≤ .008 is considered statistically significant after a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Significantly compartmentalized tests are shown in bold.

c Monotypic sequences were not collapsed in this analysis because of insufficient numbers of sequences.

Table 4.

Longitudinal Analyses of Compartmentalization of HIV env Sequences

| Subject ID | SMa,b | SM Monotypic Virus Collapsed to a Single Sequencec | Snna,b | Snn Monotypic Virus Collapsed to a Single Sequencec | Total Migrationd Events | Migration Events From Plasma to Cervix (%)d | Migration Events From Cervix to Plasma (%)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <.001 | .04 | .002 | .90 | 15 | 13 (87) | 2 (13) |

| 2 | <.001 | .09 | <.001 | .07 | 10 | 4 (40) | 6 (60) |

| 3 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .03 | 17 | 13 (76) | 4 (24) |

| 4 | .03 | NA | .31 | NA | 28 | 25 (89) | 3 (11) |

| 5 | .03 | NA | .74 | NA | 17 | 9 (53) | 8 (47) |

| 6 | .37 | NA | .03 | NA | 15 | 13 (87) | 2 (13) |

| 7 | .14 | NA | .31 | NA | 19 | 14 (74) | 5 (26) |

| 8 | .07e | NA | .007 | .59 | 12 | 7 (58) | 5 (42) |

Derived from plasma vs genital secretions.

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NA, not applicable; SM, Slatkin–Maddison test; Snn, Hudson nearest neighbor test.

b P ≤ .008 is considered statistically significant after a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Significantly compartmentalized tests are shown in bold type.

c Monotypic sequences in subjects with significant compartmentalization were collapsed into a single sequence then evaluated for compartmentalization using SM and Snn.

d Migration events and direction were calculated by the SM test as implemented in HyPhy [37].

f SM test for this person did not show significant compartmentalization by SM, and therefore we did not collapse the monotypic sequences to a single sequence.

Review of the phylogenetic trees identified 6 tissue-specific clades (Figure 1); 3 clades consisted of genital tract sequences, and 3 consisted of plasma sequences. However, none of these tissue-specific clades persisted over time as viral lineages. Across all 8 subjects, 16 viral lineages were identified. Of these, 15 of 16 (94%) were comprised of a mixture of genital tract and blood sequences (Figure 1). Subject 4 had a plasma lineage (Figure 1). No genital tract–specific lineages were observed.

A total of 133 migration events between the 2 tissues were detected across the 8 women. A greater number of migration events were observed from plasma to cervix (mean, 13; range, 4–25) compared with cervix to plasma (mean, 5; range, 2–8; P < .02) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Our primary finding is that although HIV was markedly compartmentalized between the genital tract and blood in cross-sectional analyses of approximately half the women studied, over time these viruses did not evolve to form genital tract–specific HIV lineages. The compartmentalization detected at single time points appears driven by identical and low-diversity sequences, and their transient nature suggests that they are produced by bursts of viral replication. The absence of genital-specific lineages suggests that viruses do not commonly replicate within the genital tract in isolation from variants in the blood and that HIV traffics between these tissues. Viral migration was predominately from the plasma to the cervix in our subjects, a pattern consistent with T-cell migration from the periphery into genital tissues.

Across 9 cross-sectional studies, HIV env sequences were compartmentalized between the female genital tract and blood in 33 of 65 (51%) subjects [13, 14, 18, 19, 23, 26–29]. Coreceptor usage has been associated with compartmentalization [14, 23, 47] but could not be assessed in our study because only 1 subject had a single env sequence predicted to have an X4 phenotype. Viruses with a higher number of pNLG were detected predominantly in the genital tract of our subjects, as observed by others [12, 14, 23], suggesting greater immune pressures in the genital tract. Fluctuations in the menstrual cycle could impact compartmentalization but was not examined in this study because women were consistently sampled during their luteal phase [33]. Sexually transmitted infections and inflammatory conditions of the genital tract did not appear related to compartmentalization in this small population of women.

Monotypic sequences contributed substantially to compartmentalization of viruses in our study. Monotypic viruses have been identified in our and others’ cross-sectional studies [13, 14, 18, 19, 26–29] and from 1 longitudinal study [11]. However, monotypic viruses have not previously been described as a factor that drives compartmentalization of HIV [13, 14, 18, 26]. In others’ studies, monotypic viruses derived by cloning the amplicon of a single PCR were appropriately excluded from phylogenetic analysis because of the possibility that these sequences may have resulted from resampling of the amplicon [11, 13]. Of note, even after the exclusion of monotypic sequences [11, 13], low-diversity viral variants (<1% genetic distance) [11, 13, 14, 18, 19] likely from ongoing viral replication, appear to drive compartmentalization in 18 of 33 (54%) of subjects in previous studies [14, 18, 19].

In the majority of women we studied, monotypic sequences were more frequently derived from the genital secretions than the blood, even in women without compartmentalization, as we previously noted with cell-associated HIV [28, 29]. The propensity to detect monotypic variants in the genital tract could result from differences in immune proliferative responses at mucosal sites compared with the blood or in immune selection between the 2 sites, as suggested by the pNLG data. The sampling of small volumes of genital secretions that do not circulate like blood could capture monotypic viruses in the genital tract produced from relatively few cells. In addition, the plasma likely includes viral variants from multiple tissues that may vary in selective pressures on the virus.

The 2 published longitudinal studies examined genital and blood sequences from a combined total of 15 women. One study of cell-free and cell-associated HIV env sequences from 3 acutely HIV-infected women [11] had a preponderance of blood sequences (278 of 355, 78%), which increased the likelihood that genital viruses would be absent from some viral lineages. The genetic distance of approximately 10% in 1 of 2 lineages of 1 subject suggests a dual or super-infection, which was fairly common in this Kenyan cohort that included sex workers [11, 48]. Importantly, similar to our study of chronically infected women, genital tract–specific HIV lineages were not noted in these 3 acutely infected women [11].

The second longitudinal study used heteroduplex tracking assay and identified unique genital tract viral sequences that persisted over time [16]. Heteroduplex tracking assay depends on the mobility of DNA duplexes and segregates amplicons based on the tertiary structure of DNA duplexes rather than the genetic relatedness of viral sequences. Therefore, heteroduplex tracking assay does not evaluate genetic evolution and cannot detect viral lineages.

Limitations of our study include that genital sequences were primarily derived from the cervical os secretions. Sampling this small anatomic region may limit our ability to detect viral lineages. Although SGA of CVL was performed, the sequence yield was sparse, and those generated clustered with sequences from the cervical os (Figure 1, subject 4). An additional limitation is that only 8 subjects were studied, and genital tract lineages may occur in a minor subset of individuals that we did not capture in this cohort.

In summary, viral compartmentalization of HIV env genital tract and blood sequences was detected in cross-sectional analysis due to monotypic sequences likely produced from bursts of viral replication. Importantly, compartmentalization of HIV variants was a transient phenomenon in our study because the monotypic variants did not persist over time to form genital tract–specific lineages. HIV variants migrated between the tissues, primarily from the blood into the genital tract viral population, which likely impeded the evolution of genital tract–specific viral lineages.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgements. The authors would like to acknowledge the women who participated in the Women's HIV Interdisciplinary Network study and the work of the clinical personnel (Lauren Asaba, Jane Reid, and Norma Nunez).

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (PO1 HD 40540–01 to R. W. C.; R56AI091550 to L. M. F.; R01 AI071212 to L. M. F.; R01 AI091550 to L. M. F.); by the the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) STD/AIDS Fellowship (AI 07140 to MEB); and by the University of Washington CFAR, an NIH-funded program (P30 AI027757), which is supported by the following NIH institutes: NIAID, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Child Health and Development, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, and National Institute on Aging (to J. I. M., R. W. C., and S. E. H.).

Potential conflict of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed

References

- 1.Keele BF, Giorgi EE, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, et al. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7552–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottlieb GS, Heath L, Nickle DC, et al. HIV-1 variation before seroconversion in men who have sex with men: analysis of acute/early HIV infection in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1011–5. doi: 10.1086/529206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Keele BF, et al. Genetic identity, biological phenotype, and evolutionary pathways of transmitted/founder viruses in acute and early HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1273–89. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kearney M, Maldarelli F, Shao W, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 population genetics and adaptation in newly infected individuals. J Virol. 2009;83:2715–27. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01960-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer W, Ganusov VV, Giorgi EE, et al. Transmission of single HIV-1 genomes and dynamics of early immune escape revealed by ultra-deep sequencing. PLoS One. 5:e12303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H, Bar KJ, Wang S, et al. High multiplicity infection by HIV-1 in men who have sex with men. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000890. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Taylor ME, et al. Genetic variation in HTLV-III/LAV over time in patients with AIDS or at risk for AIDS. Science. 1986;232:1548–53. doi: 10.1126/science.3012778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes EC, Zhang LQ, Simmonds P, Ludlam CA, Brown AJ. Convergent and divergent sequence evolution in the surface envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 within a single infected patient. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4835–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.4835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korber BT, Kunstman KJ, Patterson BK, et al. Genetic differences between blood- and brain-derived viral sequences from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients: evidence of conserved elements in the V3 region of the envelope protein of brain-derived sequences. J Virol. 1994;68:7467–81. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7467-7481.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shankarappa R, Margolick JB, Gange SJ, et al. Consistent viral evolutionary changes associated with the progression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1999;73:10489–502. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10489-10502.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poss M, Rodrigo AG, Gosink JJ, et al. Evolution of envelope sequences from the genital tract and peripheral blood of women infected with clade A human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:8240–51. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8240-8251.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haaland RE, Sullivan ST, Evans-Strickfaden T, Lennox JL, Hart CE. Female genital tract shedding of CXCR4-tropic HIV type 1 is associated with a majority population of CXCR4-tropic HIV type 1 in blood and declining CD4(+) cell counts. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2012;11:1524–32. doi: 10.1089/AID.2012.0004. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2524.2003.00440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andreoletti L, Skrabal K, Perrin V, et al. Genetic and phenotypic features of blood and genital viral populations of clinically asymptomatic and antiretroviral-treatment-naive clade a human immunodeficiency virus type 1–infected women. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1838–42. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00113-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kemal KS, Foley B, Burger H, et al. HIV-1 in genital tract and plasma of women: compartmentalization of viral sequences, coreceptor usage, and glycosylation. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12972–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134064100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goulston C, McFarland W, Katzenstein D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA shedding in the female genital tract. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1100–3. doi: 10.1086/517404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan ST, Mandava U, Evans-Strickfaden T, Lennox JL, Ellerbrock TV, Hart CE. Diversity, divergence, and evolution of cell-free human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in vaginal secretions and blood of chronically infected women: associations with immune status. J Virol. 2005;79:9799–809. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9799-9809.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chomont N, Hocini H, Gresenguet G, et al. Early archives of genetically-restricted proviral DNA in the female genital tract after heterosexual transmission of HIV-1. AIDS (London) 2007;21:153–62. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328011f94b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Philpott S, Burger H, Tsoukas C, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomic RNA sequences in the female genital tract and blood: compartmentalization and intrapatient recombination. J Virol. 2005;79:353–63. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.353-363.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaudhary S, Noel RJ, Rodriguez N, et al. Correlation between CD4 T cell counts and virus compartmentalization in genital and systemic compartments of HIV-infected females. Virology. 2011;417:320–6. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Si-Mohamed A, Kazatchkine MD, Heard I, et al. Selection of drug-resistant variants in the female genital tract of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected women receiving antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:112–22. doi: 10.1086/315679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Min SS, Corbett AH, Rezk N, et al. Protease inhibitor and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor concentrations in the genital tract of HIV-1-infected women. J Acq Immun Def Synd (1999) 2004;37:1577–80. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200412150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawn SD, Subbarao S, Wright TC, Jr., et al. Correlation between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA levels in the female genital tract and immune activation associated with ulceration of the cervix. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1950–6. doi: 10.1086/315514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellerbrock TV, Lennox JL, Clancy KA, et al. Cellular replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 occurs in vaginal secretions. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:28–36. doi: 10.1086/321000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovacs A, Wasserman SS, Burns D, et al. Determinants of HIV-1 shedding in the genital tract of women. Lancet. 2001;358:1593–601. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06653-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panther LA, Tucker L, Xu C, Tuomala RE, Mullins JI, Anderson DJ. Genital tract human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) shedding and inflammation and HIV-1 env diversity in perinatal HIV-1 transmission. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:555–63. doi: 10.1086/315230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poss M, Martin HL, Kreiss JK, et al. Diversity in virus populations from genital secretions and peripheral blood from women recently infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1995;69:8118–22. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.8118-8122.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adal M, Ayele W, Wolday D, et al. Evidence of genetic variability of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in plasma and cervicovaginal lavage in Ethiopian women seeking care for sexually transmitted infections. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2005;21:649–53. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bull M, Learn G, Genowati I, et al. Compartmentalization of HIV-1 within the female genital tract is due to monotypic and low-diversity variants not distinct viral populations. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bull ME, Learn GH, McElhone S, et al. Monotypic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genotypes across the uterine cervix and in blood suggest proliferation of cells with provirus. J Virol. 2009;83:6020–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02664-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tobin NH, Learn GH, Holte SE, et al. Evidence that low-level viremias during effective highly active antiretroviral therapy result from two processes: expression of archival virus and replication of virus. J Virol. 2005;79:9625–34. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9625-9634.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bailey JR, Sedaghat AR, Kieffer T, et al. Residual human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viremia in some patients on antiretroviral therapy is dominated by a small number of invariant clones rarely found in circulating CD4+ T cells. J Virol. 2006;80:6441–57. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00591-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brennan TP, Woods JO, Sedaghat AR, Siliciano JD, Siliciano RF, Wilke CO. Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viremia and provirus in resting CD4+ T cells reveals a novel source of residual viremia in patients on antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 2009;83:8470–81. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02568-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reichelderfer PS, Coombs RW, Wright DJ, et al. Effect of menstrual cycle on HIV-1 levels in the peripheral blood and genital tract. WHS 001 Study Team. AIDS (London) 2000;14:2101–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200009290-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slatkin M, Maddison WP. A cladistic measure of gene flow inferred from the phylogenies of alleles. Genetics. 1989;123:603–13. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.3.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Critchlow DEL, Shuying L, Nourijelyani K, Pearl DK. Some statistical methods for phylogenetic trees with application to HIV fisease. Math Comp Model. 2000;32:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hudson RR. A new statistic for detecting genetic differentiation. Genetics. 2000;155:2011–4. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.4.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pond SL, Frost SD, Muse SV. HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:676–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitchell CM, Balkus J, Agnew KJ, et al. Bacterial vaginosis, not HIV, is primarily responsible for increased vaginal concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2008;24:667–71. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchell C, Paul K, Agnew K, Gaussman R, Coombs RW, Hitti J. Estimating volume of cervicovaginal secretions in cervicovaginal lavage fluid collected for measurement of genital HIV-1 RNA levels in women. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:735–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00991-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zuckerman RA, Whittington WL, Celum CL, et al. Higher concentration of HIV RNA in rectal mucosa secretions than in blood and seminal plasma, among men who have sex with men, independent of antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:156–61. doi: 10.1086/421246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guindon S, Lethiec F, Duroux P, Gascuel O. PHYML Online—a web server for fast maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic inference. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W557–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deng W, Maust BS, Nickle DC, et al. DIVEIN: a web server to analyze phylogenies, sequence divergence, diversity, and informative sites. Biotechniques. 2010;48:405–8. doi: 10.2144/000113370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holmes EC, Zhang LQ, Simmonds P, Ludlam CA, Leigh Brown AJ. Convergent and divergent sequence evolution in the surface envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 within a single infected patient. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4835–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.4835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Page RDM, Holmes EC. Molecular evolution: a phylogenetic approach. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zarate S, Pond SL, Shapshak P, Frost SD. Comparative study of methods for detecting sequence compartmentalization in human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2007;81:6643–51. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02268-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell C, Hitti J, Paul K, et al. Cervicovaginal shedding of HIV type 1 is related to genital tract inflammation independent of changes in vaginal microbiota. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2011;27:35–9. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Delwart EL, Mullins JI, Gupta P, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 populations in blood and semen. J Virol. 1998;72:617–23. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.617-623.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin HL, Jr, Nyange PM, Richardson BA, et al. Hormonal contraception, sexually transmitted diseases, and risk of heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1053–9. doi: 10.1086/515654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodrigo AG, Goracke PC, Rowhanian K, Mullins JI. Quantitation of target molecules from polymerase chain reaction-based limiting dilution assays. AIDS AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 1997;13:737–42. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.