Abstract

Psychopathy has been associated with increased putamen and striatum volumes. The nucleus accumbens –a key structure in reversal learning, less effective in psychopathy –has not yet received specific attention. Moreover, basal ganglia morphology has never been explored. We examined the morphology of the caudate, putamen and accumbens, manually segmented from magnetic resonance images of 26 offenders (age: 32.5±8.4) with medium-high psychopathy (mean PCL-R=30±5) and 25 healthy controls (age: 34.6±10.8). Local differences were statistically modeled using a surface-based radial distance mapping method (p<0.05; multiple comparisons correction through permutation tests). In psychopathy, the caudate and putamen had normal global volume, but different morphology, significant after correction for multiple comparisons, for the right dorsal putamen (permutation test: p=0.02). The volume of the nucleus accumbens was 13% smaller in psychopathy (p corrected for multiple comparisons <0.006). The atypical morphology consisted of predominant anterior hypotrophy bilaterally (10–30%). Caudate and putamen local morphology displayed negative correlation with the lifestyle factor of the PCL-R (permutation test: p=0.05 and 0.03). From these data, psychopathy appears to be associated with an atypical striatal morphology, with highly significant global and local differences of the accumbens. This is, consistent with the clinical syndrome and with theories of limbic involvement.

Keywords: psychopathy, neuroimaging, basal ganglia, nucleus accumbens, MRI, ASPD

1. Introduction

Psychopathy is a personality disorder characterized by shallow affect, a callous lack of empathy or remorse, and an inclination to a parasitic and impulsive lifestyle, often leading to criminal behavior (Hare & Neumann, 2008). Recent research on brain morphology has detected morphological differences in the brain structures of individuals with psychopathy, although differences in the methods used have led to inconsistent results (Koenigs et al., 2010). Differences have been reported in cortical and subcortical regions (Boccardi et al., 2011; de Oliveira-Souza et al., 2008; Muller et al., 2008; Tiihonen et al., 2008; Yang, Raine, Colletti, Toga, & Narr, 2009). Among these, the basal ganglia are crucial for emotional processing and behavioral planning, particularly via their connections with the amygdala and the frontal lobe, within the limbic circuit (Devinsky, Morrell, & Vogt, 1995; Vogt, Finch, & Olson, 1992). Indeed, the hypothesis that psychopathic behavior may correlate with differences in the limbic structures and connections has been repeatedly corroborated (Craig et al., 2009; Kiehl, 2006; Raine, Lee, Yang, & Colletti, 2010).

Some morphometric studies have found striatal volume alterations in conditions associated with violent behavior. One study found greater global volumes of the putamen in a group of subjects with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) subjects (Barkataki, Kumari, Das, Taylor, & Sharma, 2006), which was interpreted as possibly related to impulsivity and poor behavioral control. A second study (Glenn, Raine, Yaralian, & Yang, 2010) examined the volume of the entire striatum, of the nucleus lenticularis (putamen and pallidus), and of the caudate head and body, in psychopathy. It found a 9.6% increase for the whole striatum, and similar enlargement of the nucleus lenticularis, bilaterally; findings were interpreted as connected to the increased stimulation seeking and impairments in reinforcement learning in psychopathy. A recent voxel-based morphometry (VBM) study detected greater local gray matter volume in the right caudate and in the left accumbens nuclei in offenders with sub-threshold psychopathy scores (Schiffer et al., 2011).

Nonetheless, only global volumes, or local gray matter density in voxel-based analyses, were examined, and information on the actual 3D shape of the basal ganglia is lacking to date. Moreover, the previous studies did not carry out specific region-of-interest analyses for the nucleus accumbens, the critical basal ganglia nucleus connecting to the amygdala and the orbitofrontal cortex within the anterior limbic circuit (Devinsky et al., 1995; Vogt et al., 1992), which is known to be involved in psychopathy (Boccardi et al., 2011; de Oliveira-Souza et al., 2008; Kiehl, 2006; Raine et al., 2010; Yang, Raine, Narr, Colletti, & Toga, 2009). The accumbens is a key structure in reversal learning, i.e., the ability to overwrite on previously learned knowledge as context conditions change. Particularly, individuals need to take experience into account, and update the values that they attributed to stimuli or goals, as well as knowledge about the effects of their own behavior. A goal, or a behavior, that turned out to be good value in the past may not be worth or useful in a different time or context, so the individual must overwrite on prior knowledge in order to engage in more adaptive actions. Considering the limited ability of people with psychopathy to learn from experience, and that many are refractory to different kinds of treatment or correctional contexts, the accumbens is a particularly interesting target for neuroscientific investigation, to assess the neurobiological correlates of the cognitive and volitional capacities generating behavior in psychopathy.

Here we aimed to quantify the global volume of the caudate, putamen and accumbens nuclei, and to map local morphological differences using the radial distance mapping algorithm. We examined a sample of criminal offenders with psychopathy as defined by the Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R), lacking disorders in the schizophrenia spectrum, which are associated with independent brain alterations in individuals with violent behavior (Narayan et al., 2007).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Subjects

Study subjects with psychopathy, already described in detail (Boccardi et al., 2010; Boccardi et al., 2011; Tiihonen et al., 2008), included 26 habitually violent male offenders, consecutively admitted to a university forensic psychiatric hospital for pre-trial assessment, and currently charged with a violent offence. They fulfilled criteria for DSM-IV ASPD and ICD-10 dissocial personality, had no history or current diagnosis of psychosis or schizotypal personality disorder, had additional cluster B personality disorders and met criteria for substance abuse.

The PCL-R was used to assess psychopathy (Hare, 2003) by a certified psychiatrist.

Twenty-five healthy men volunteers of similar age, free from current or past substance abuse, were recruited among students, hospital staff and skilled workers, after giving informed consent (Boccardi et al., 2010; Tiihonen et al., 2008). The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and case record files of the offenders were obtained retrospectively from hospital files, after approval by the ethics committee of the Kuopio University Hospital.

2.2 Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRIs were acquired on a 1.0 T Impact scanner (Siemens; Erlangen, Germany) using a standard head coil and a tilted T1-weighted coronal 3D gradient echo sequence (magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo: TR 10 ms, TE 4 ms, TI 250 ms, flip angle 12!, FOV 250 mm, matrix 256"192, 1 acquisition). The three-dimensional spatial resolution was 2.0 mm × 1.3 mm × 0.97 mm.

2.3 Image processing

The 3D images were re-sampled to an isotropic voxel size of 1 mm, reoriented along the AC-PC line, and voxels below the cerebellum were manually removed with MRIcro (http://www.sph.sc.edu/comd/rorden/mricro.html). The anterior commissure was manually set as the origin of the spatial coordinates for an anatomical normalization algorithm implemented as part of Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM2) software package (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm2/). A 12-parameter affine transformation was used to spatially normalize each image to a customized template in stereotaxic space, created from the MRI scans of all study subjects.

2.4 Manual segmentation

The putamen, caudate and accumbens of offenders and controls were manually traced by a single tracer (Martina Bocchetta), blind to diagnosis, following an optimized protocol based on the selection of landmarks and criteria from three validated protocols (Gunning-Dixon, et al., 1998; Hokama et al., 1995; Makris et al., 1999). Criteria were chosen if they: 1) included more of the selected region of interest (ROI), 2) were better defined, or 3) were the most often used. Intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) were previously obtained on an independent sample of 10 controls from a local dataset (Galluzzi et al., 2009), scanned with a machine of the same magnet strength as that used for the sample of psychopathic and healthy subjects examined here,. The intra-rater reliability measures were 0.92 for the accumbens and caudate, 0.98 for the putamen; the reference for the computation of inter-rater reliability consisted in the segmentation of the basal ganglia of the same subjects by another tracer, expert of cerebral anatomy (Enrica Cavedo). Inter-rater measures were 0.83 for the accumbens, 0.89 for the putamen and 0.91 for the caudate.

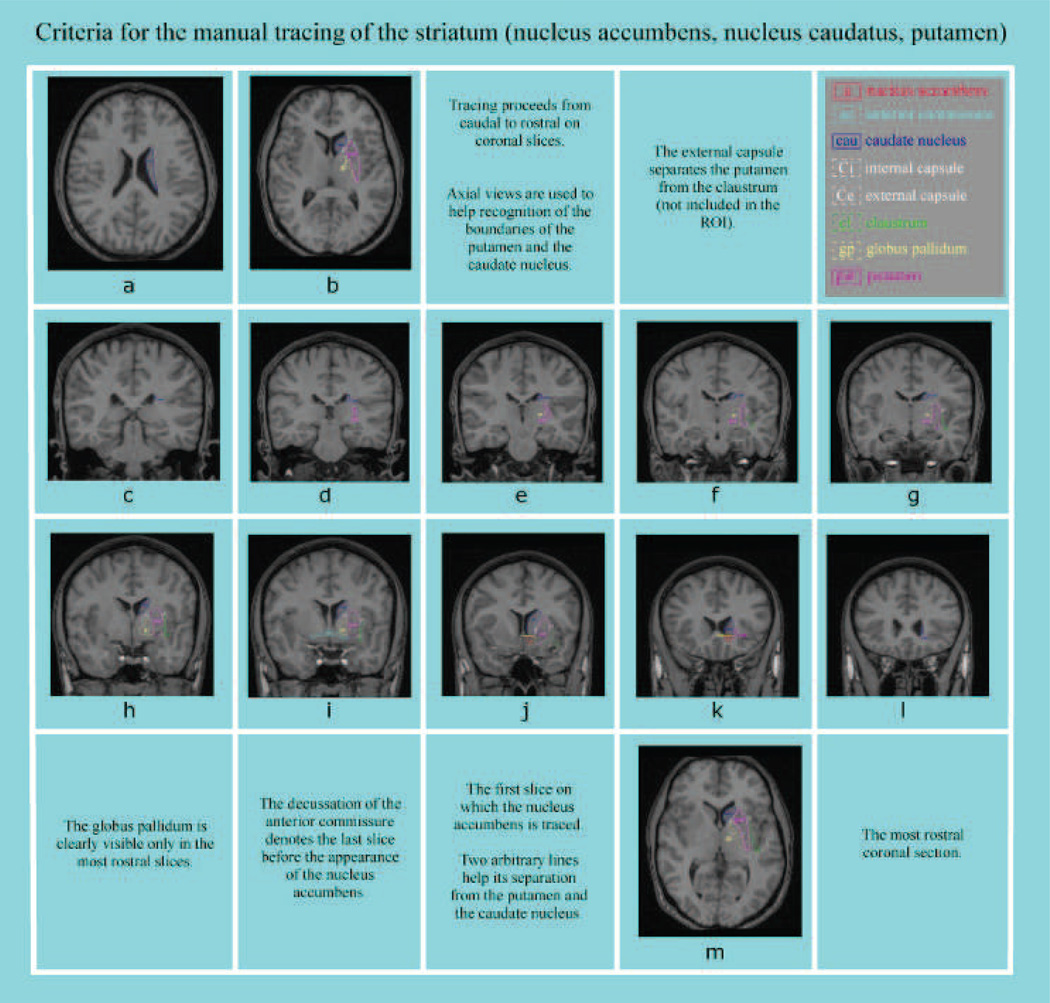

2.4.1 Criteria for manual segmentation of the nucleus accumbens, caudate nucleus and putamen from magnetic resonance images

Tracing proceeds on contiguous coronal brain sections from caudal to rostral. For a slice thickness of 1 mm, approximately 15 slices include the accumbens, 60 the caudatus, 50 the putamen.

Accumbens

Tracing starts (Figure 1, j) on the section rostral to the slice where the anterior commissure decussates (Figure 1, i), and stops (Figure 1, k) when the putamen is no longer visible in the coronal section, as confirmed by the axial view. The separation of the accumbens from the putamen and the caudate is helped by the tracing of two arbitrary lines. A horizontal line tangent the inferiormost tip of the lateral ventricle distinguishes any superior gray matter, characterized by a lighter gray than the accumbens, as belonging to the caudate (yellow line in the Figure 1, j–k); a vertical line drawn from the most inferior point of the internal capsule, upwards to the caudatus, discriminates any lateral gray matter as belonging to the ventral putamen (green line in the Figure, j–k) (Makris et al., 1999).

Figure 1.

Segmentation protocol for the striatum.

Caudate

The tracing of the caudate includes the head, the body, and the tail, as long as it is adjacent to the lateral ventricle, and excludes the caudal portion curving in the anteroventral direction (Hokama et al., 1995). The tracing starts on the most caudal slice (Figure 1, c) on which the tail is adjacent to the lateral ventricle, as also visible on the axial plane (Figure 1, a). The head is traced until it is no longer visible, on the most rostral section on which the nucleus is usually adjacent to the lateral ventricle (Figure 1, l), as confirmed on the axial view (Figure 1, m). The caudate is bordered medially by the lateral ventricle, laterally by the internal capsule and dorsally by lobar white matter (Figure 1, c–l).

Putamen

The putamen is traced in all slices where it is visible (Figure 1, d–k), starting on the coronal section where it appears as a thin mass of gray matter located infero-laterally to the caudatus (Figure 1, d). On the most caudal slices the identification of the nucleus is helped by the axial view: here the putamen is visible as a comma-shaped gray nucleus (Figure 1, b–m). Laterally (in coronal slices), it is demarcated by the external capsule, which separates it from the claustrum (not included in the tracing), which first appears when the putamen tends to curve into the temporal lobe (Figure 1, f). The dorsal boundary consists of the white matter of the internal capsule. In the caudal and central slices the medial border is drawn along the hyperintense region corresponding to the external medullar lamina and adjacent pallidum (Figure 1, d–i). From the first slice after the decussation of the anterior commissure (which is ventral to the putamen) to rostral, the internal capsule and the nucleus accumbens demarcate the medial boundary (Gunning-Dixon et al., 1998) (Figure 1, j–k). The tracing stops when the putamen is no longer visible, as it can easily be confirmed by 3D navigation.

2.5 Radial distance mapping (RDM)

Three-dimensional parametric surface mesh models were generated for each of the manually segmented structures in each subject (Narr et al., 2004; Thompson et al., 2004). Slices were re-sampled and re-sliced to obtain 150 uniformly spaced levels that allow the computational matching of points in a standard mesh model. Mathematical details for interpolating the striatal shape between image slices are presented elsewhere (Thompson, Schwartz, & Toga, 1996). On each re-sampled slice, the radial directions were defined at each surface point as its shortest distance to a centerline threading down the centroid of the structure in each slice. These procedures allow measurements at corresponding surface locations across subjects and statistical comparisons between groups (Thompson et al., 1996).

The correspondence of the 3D parametric mesh models of each individual’s nuclei was automatically computed by matching homologous uniformly spaced points on the surface contour. To assess striatal morphology, a medial curve was automatically defined as the 3D curve traced out by the centroid of the each striatal structure’s boundary in each image slice. The radial size of each nucleus, at each boundary point, was assessed by measuring the length of the radial directions (shortest lines connecting each surface point to the centroid of the slice). Shorter and longer radial distances were used as an index of relative atrophy or enlargement, respectively, and analyzed to estimate systematic differences in morphology between offenders and controls. These differences were finally mapped in color code at the corresponding surface points (Thompson et al., 1996; Thompson et al., 2004).

Global volumes of each structure, already normalized for cranial size due to the previous spatial normalization, were also computed from the same tracings.

2.6 Statistical analysis

For all variables, Levene’s test for the homogeneity of variance and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for the normality of data distribution were carried out, to determine whether parametric testing was appropriate. Student’s t-tests and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare demographic, clinical and global volume data in cases versus controls. To keep into account the number of comparisons carried out to examine the global volume of the striatal nuclei (three nuclei by side, for a total of six comparisons) we used a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, and divided the p threshold of 0.05 by 6 (number of comparisons each experiment). We thus accepted as statistically significant a p value of 0.008 for the global volume analyses.

T-tests were used to evaluate local significant differences at each point in the RDM procedure, in the comparison between offenders and controls, and in subgroup comparisons (i.e., high psychopathy versus medium psychopathy, medium psychopathy versus controls, high psychopathy versus controls). PCL-R total and subfactor scores were used as covariates to generate 3-D maps of Pearson’s R, and to show significant correlations with striatum morphology in the offenders. P values were computed for the maps at the surface level, and a pointwise significance threshold was set to p<0.05. Maps of pointwise significance levels and percent differences were visualized using a color code on 3D models of the structure. Furthermore, a permutation method was applied to all maps to provide an overall p value for the effects, that was corrected for multiple comparisons (Thompson et al., 2003).

Permutation methods basically measure the probability that the observed distribution of a given feature (e.g., the number of vertices with statistics below p<0.05 in the entire map) would occur by accident if the subjects were randomly assigned to groups. The effect observed in the random assignments was then compared to that observed in the true experiment. This calculation was made by computing the number of times that an effect with a similar or greater magnitude occurred in the random assignments compared to the true assignments, over the total number of “random” experiments run. This ratio represents the empirical probability that the observed pattern occurred by accident, and it provides an overall significance value for reliability of the map, corrected for multiple comparisons (Thompson et al., 2003). More specifically, 10,000 permutations of the assignments for subjects to groups were computed, while keeping the total number of subjects in each group the same, in order to carry out 10,000 random experiments. In each of these experiments, instead of assigning 0 to cases and 1 to controls, as in the true experiment, the assignments of 0 and 1 to cases and controls was randomly scrambled (permuted). For each of these 10,000 permutations, the p-map of the differences for the “cases” (all individuals randomly assigned to group 0) versus “controls” (all individuals randomly assigned to group 1) was generated point by point along the whole 3D hippocampal mesh model, and a new p-map was obtained for each random experiment. Subsequently, the number of supra-threshold (i.e., significant) voxels was computed and compared between each random experiment and the true experiment. In the whole set of the 10,000 experiments, the total number of times that the supra-threshold count was equal or higher than that observed in the true experiment was divided by 10.000 (i.e., the number of random experiments carried out), and this estimated the probability that a map, with an amount of significant local differences greater than or equal to that observed in the true experiment, could be obtained by chance.

We note that the this use of the supra-threshold volume of statistics is analogous to set-level inference in functional imaging (Frackowiak et al., 2003). Other types of permutation tests are possible, examining the distribution of the size of the largest supra-threshold cluster, or the peak height (maximum statistic), etc. In general, we choose the supra-threshold volume statistic as it allows the detection of diffuse effects that occur weakly across the surface of a structure so long as they are present at larger number of voxels that would be expected by chance alone. This is very similar to analyses that control the false discovery rate (Hochberg and Benjamini, 1990; Genovese et al., 2002), where the supra-threshold counts are analyzed using a histogram.

Throughout this paper, we thus refer to different kinds of p values. The p values reported in the figures are those resulting from the direct comparisons of cases and controls. These p values are those related to the specific effect size and power of our experiment. We then provide additional p values denoting the survival of such results in the permutation test for correcting for multiple comparisons. When this p value at permutation testing is significant, the original p values can also be considered as “corrected” p values. In both cases, the threshold for significance was 0.05.

The RDM technique, reconstructing 3D mesh models from the manual segmentations, generates for each structure a “dorsal” and a “ventral” map that separately undergo statistical investigation. P values at permutation testing are computed for both the dorsal and ventral maps of each of the examined structures, independently. Whenever both the dorsal and ventral maps were significant at permutation testing, a single value (consisting in a mean value among the two) was provided to simplify reading. If only one map was significant, this is explicitly reported, along with the correspondent original corrected p value. The distinct dorsal and ventral maps separately tested on permutation testing can be easily recognized in the Figures, being demarcated by longitudinal seem-like lines that interrupt the continuity of the surface, and that indeed separate a dorsal aspect from a ventral aspect. It should be noticed that this separation is not linked to any kind of anatomical landmark, but only relates to the features of the algorithm reconstructing the 3D mesh models of the anatomical structure. In the case of the caudate nucleus, the separation between a “dorsal” and a “ventral” aspect is less straightforward: the “dorsal” map corresponds to the dorsomedial aspect (all the region located dorsomedially to the seem-like longitudinal line), and the “ventral” map corresponds to the ventrolateral aspect.

3. Results

Offenders scored highly on the PCL-R evaluation; the mean group score was 29.9±5.2. When subjects were divided into those above and below a score of 30 on the PCL-R, the 14 subjects scoring lower than 30 still had a PCL-R mean score of 25.9 (±2), compatible with medium severity of psychopathy. The 12 subjects with high psychopathy differed significantly from the 14 with medium psychopathy on Factor 1 (Interpersonal), Factor 2 (Affective), and Factor 4 (Antisocial, please see Table 1). Polysubstance abuse was also significantly more prevalent in the high psychopathy subgroup (Table 1). Offenders and controls (all men) had similar age.

Table.

Sociodemographic, clinical and basal ganglia volumetric features in 26 offenders with psychopathy and 25 controls. P values of volumetric basal ganglia, significant after correction for multiple comparisons are reported in bold.

| Controls (N = 25) |

Violent offenders (N = 26) |

P-value (Controls vs Offenders) |

High PCL-R (N=12) |

Medium PCL-R (N=14) |

P-value (High vs Medium) |

P-value (High vs Controls) |

P-value (Medium vs Contrl) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 34.6 ± 10.8 | 32.5 ± 8.4 | 0.438 | 33.0 ± 8.6 | 32.1 ± 8.5 | 0.800 | --- | --- |

| Alcohol dependence, % | 0 | 100% | --- | 100% | 100% | --- | --- | --- |

| Age onset of alcohol abuse | --- | 13.6 ± 2.9 | --- | 13.3 ± 2.71 | 13.79 ± 3.09 | 0.697 | --- | --- |

| Polysubstance abuse, % | 0 | 77% | --- | 100% | 57% | 0.017 | --- | --- |

| Duration of alcohol abuse, years | --- | 18.93 ± 9.2 | --- | 19.6 ± 10.0 | 18.3 ± 8.9 | 0.725 | --- | --- |

| Amphetamine use, % | 0 | 58% | --- | 75% | 43% | 0.130 | --- | --- |

| Current psychotropic medication, % | 0 | 58% | --- | 67% | 50% | 0.453 | --- | --- |

| Total intracranial volume (cm3) | 1,707 ± 117 | 1,654 ± 108 | 0.102 | 1,659 ± 86.6 | 1,649 ± 127.2 | 0.81 | --- | --- |

| Nucleus Accumbens (cm3) right | 1.41 ± 0.22 | 1.22 ± 0.23 | 0.006 | 1.23 ± 0.29 | 1.22 ± 0.18 | 0.903 | 0.046 | 0.010 |

| left | 1.34 ± 0.21 | 1.16 ± 0.19 | 0.003 | 1.18 ± 0.22 | 1.15 ± 0.17 | 0.668 | 0.040 | 0.006 |

| Caudate Nucleus (cm3) right | 4.95 ± 0.78 | 5.16 ± 0.47 | 0.251 | 5.14 ± 0.51 | 5.18 ± 0.46 | 0.825 | 0.458 | 0.325 |

| left | 5.07 ± 0.80 | 5.31 ± 0.47 | 0.188 | 5.28 ± 0.50 | 5.34 ± 0.46 | 0.738 | 0.412 | 0.250 |

| Putamen (cm3) right | 6.79 ± 0.65 | 6.83 ± 0.70 | 0.858 | 6.72 ± 0.76 | 6.92 ± 0.65 | 0.484 | 0.767 | 0.568 |

| left | 6.73 ± 0.62 | 6.77 ± 0.72 | 0.816 | 6.68 ± 0.73 | 6.85 ± 0.72 | 0.566 | 0.845 | 0.586 |

| IQ | --- | 91.5 ± 9.0 | --- | 94.7 ± 8.6 | 88.7 ± 8.8 | 0.095 | --- | --- |

| Mean score PCL-R total | --- | 29.9 ± 5.2 | --- | 34.6 ± 3.1 | 25.9 ± 2.8 | < 0.001 | --- | --- |

| Hare’s Factor 1 | --- | 3.8 ± 2.5 | --- | 6.0 ±1.8 | 1.9 ±1.1 | < 0.001 | --- | --- |

| Hare’s Factor 2 | --- | 6.9 ± 1.2 | --- | 7.8±0.6 | 6.1 ±1.1 | < 0.001 | --- | --- |

| Hare’s Factor 3 | --- | 9.7 ± 0.8 | --- | 9.7 ± 1.2 | 9.7 ± 0.5 | 0.889 | --- | --- |

| Hare’s Factor 4 | --- | 8.4 ± 1.8 | --- | 9.6 ± 0.8 | 7.5 ± 1.9 | 0.002 | --- | --- |

Global volumetric analyses of the caudate, putamen and accumbens showed distinct patterns of differences, consisting in volume reduction for the accumbens, and in a non significant increase of volume for the other two nuclei, but particularly for the caudate. In particular, bilateral tissue deficit of 13% was observed in the accumbens nuclei of offenders versus controls. This difference was significant after correction for multiple comparisons for both sides (right: p=0.006; left: p=0.003; significance threshold for p corrected for multiple comparisons: p=0.008; Table 1). The less powerful subgroup comparisons denoted a tendency to significant tissue difference in the separate comparisons of the high and of medium psychopathy subgroups versus controls, the left accumbens displaying significant smaller volume (p=0.006) in medium psychopathy (Table 1) even after correction for multiple comparisons. The mean volume of the caudate nucleus was 4–5% greater in offenders than controls, while the volume of the putamen was identical in the two groups (Table 1). These differences were not statistically significant.

3.1 Local analyses

3.1.1 Accumbens

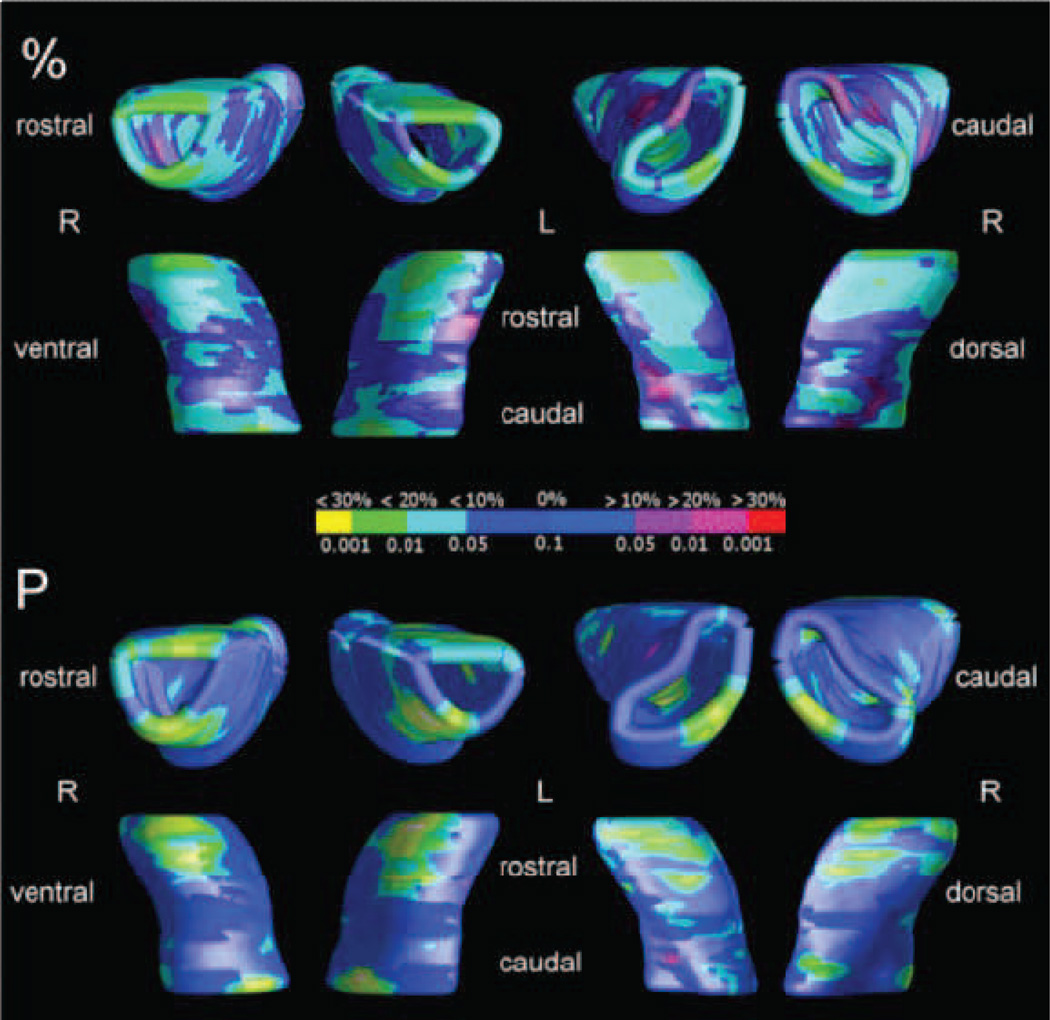

Analyses of local differences showed a symmetrical pattern of reduction and enlargement effects. Tissue reductions amounted to over 20% difference versus controls, and located mainly on the rostral part of the accumbens, on both the dorsal and ventral aspects. A 10% midline reduction and 10–20% caudal deficit could also be observed (Figure 2, upper panel). Alongside the midline reduction, small hypertrophic regions, exceeding from 10 to 30% the controls’ radial distances, characterized the atypical shape of the accumbens, that, for psychopathy, results in a more rounded shape than in controls at this level. This morphological difference was highly significant in group comparisons, local p values being below 0.001, and maps surviving the permutation tests (p=0.003 on the left; p=0.006 on the right; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Significance maps of shorter (light blue to yellow color range) and larger (red color range) radial distances in the nucleus accumbens of 26 offenders with psychopathy compared to 25 controls. Maps were significant at correction for multiple comparisons (permutation test, left: p<0.003, right: p<0.006).

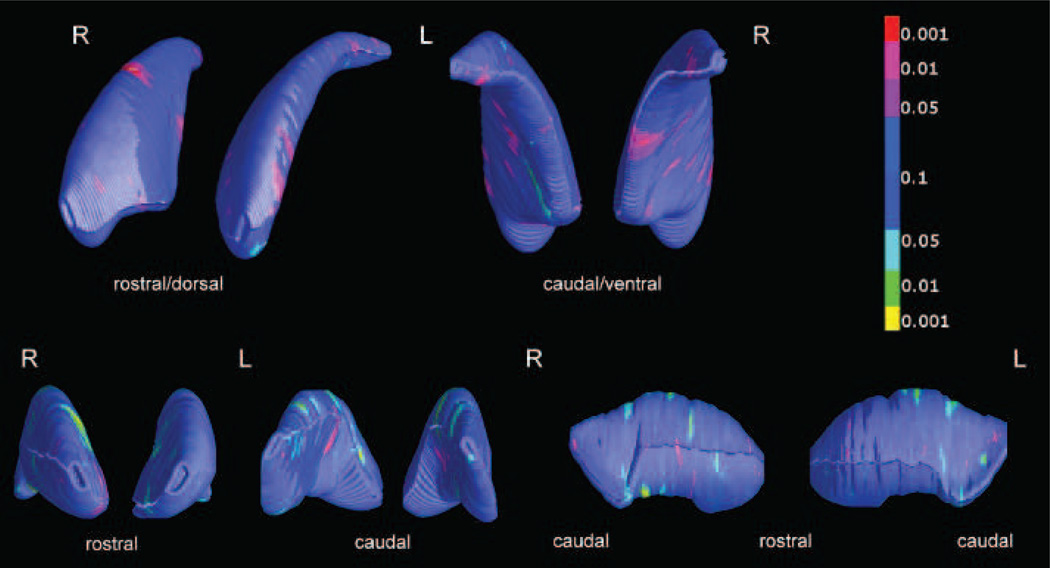

3.1.2 Caudate

The global non-significant volumetric enlargement of the caudate nucleus was accompanied by a pattern of local reduction and enlargement effects. Hypotrophic regions mapped to the right antero-ventral aspect, while the prevalent hypertrophic regions were scattered across the rest of the surface. The pattern of enlargements was roughly symmetrical across the two nuclei. P values for the observed differences were below 0.001 (Figure 3), but the p value at permutation test only approached significance for the right ventral aspect (p=0.06).

Figure 3.

Significance maps of shorter (light blue to yellow color range) and larger (red color range) radial distances in the nucleus caudatus (top panel) and putamen (bottom panel) of 26 offenders with psychopathy compared to 25 controls.

The ventral map of the right caudatus approached significance at the permutation test (p=0.06), while the dorsal map of the right putamen was significant at the permutation test (p=0.02).

3.1.3 Putamen

The putamen displayed a complex pattern of local enlargements (p<0.01) and reductions (p<0.001) on shape analysis, mapping mainly to the right (Figure 4). The right dorsal map survived permutation testing (p=0.02).

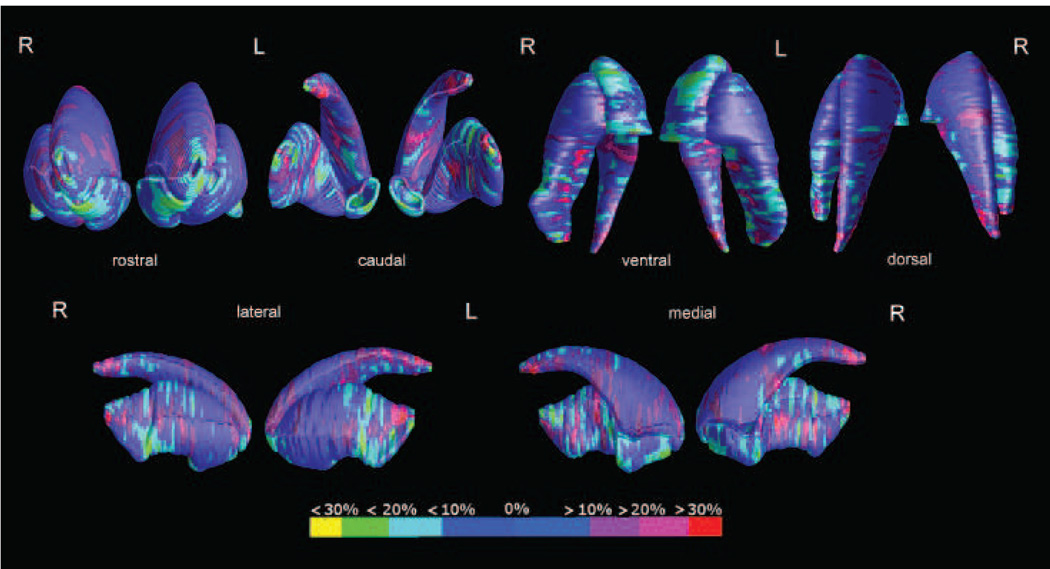

Figure 4.

Maps of local percent difference in the accumbens, caudate and putamen of the 26 psychopathy subjects compared to the 25 controls, compound in their reciprocal spatial positions. The global model allows to appreciate the entire morphology of the whole striatum in psychopathy.

3.2 Supplementary analyses

Supplementary analyses were aimed to further investigate morphological features in the subgroups of high and medium psychopathy, to examine the relationship of morphology with the clinical phenotype as quantified at the PCL-R evaluation, and to try to discern whether the findings reported so far could be a consequence of substance abuse. Results of these analyses are available as Supplementary Online Material at: www.centroalzheimer.it/public/MB/psycho/BasalGangliaPsychos_SupplFigs.pdf.

3.2.1 Subgroups comparisons

The pattern of differences found in the main analyses was replicated also after disaggregating offenders into those with high and medium PCL-R. Regions with highly significant reduction (p<0.001) and some with significant increase of tissue (p<0.01) were observed in the nuclei accumbens of both the high and medium psychopathy subgroups, and survived permutation testing (see Supplementary Figures S-1a, S-1b). Local analyses comparing medium versus high psychopathy were not significant at permutation test (Figure S-1c). Subgroup comparisons of the caudate confirmed the prevalence of local enlargements in both high and medium psychopathy, which was significant at p<0.01, but did not survive correction for multiple comparisons (Figures S-2a to S-2c).

The complex pattern of the putamen, consisting of local enlargement and reduction effects was also replicated in the subgroups of high and medium psychopathy versus controls (Figures S-3a and S-3b), and survived correction for multiple comparisons for the right dorsal aspect in the high psychopathy subgroup (Figure S-3a).

3.2.2 Correlation analyses

Within the offender group, correlation analyses of morphology with total PCL-R scores showed both positive and negative correlations with local tissue morphology, but these were not significant on the permutation test (see Figures S-4a to S-4c in Supplementary Online Material). Factor 3 (Lifestyle), instead, displayed significant correlation patterns, surviving permutation testing in the ventral map of the right caudate (corrected p=0.05) and in the right putamen (corrected p=0.03; see Figures S-5a and S-5b) (please note that in the caudate, the “ventral map” corresponds to the ventrolateral aspect, as demarcated by the longitudinal seem-like lines visible along the structure; Figure S-5a, right panel).

As to the caudate, regions of both positive and negative correlations were scattered along its length. Positive Pearson’s R values were below 0.6; instead, negative correlations exceeded R=−0.6 in the rostral pole of the right ventrolateral caudatus (see Figure S-5a, right panel). Positive correlation had a statistical significance between 0.05 and 0.01, while negative correlations had p values <0.001 (yellow spots in Figure S-5a, right bottom panel). As to the putamen, the morphology of the whole right structure was significantly correlated with Factor 3, both the dorsal and ventral maps surviving at correction for multiple comparisons, due to a similarly scattered pattern of both positive and negative correlations. Both positive and negative correlations achieved very high Pearson’s R values (see, for example, the medial and caudal yellow spots in Figure S-5b, denoting negative correlations over −0.9, and the red caudal spots indicating positive correlations of similar amount).

3.2.3 Check for substance abuse

Statistical check for substance abuse were carried out by comparing users and non-users of polysubstance (any substance besides alcohol) versus controls, amphetamine users and non users versus controls, and through direct comparisons of polysubstance users versus polysubstance non users. In the comparisons of these subgroups versus controls, the same pattern observed in the main comparisons was observed. This consisted of the same anterior and posterior hypotrophy of the accumbens on both the dorsal and ventral aspects, and of the same midline hypotrophy with regions of tissue increase alongside, and significant statistically at permutation test in the most powerful experiment of 20 subjects (polysubstance users). These data suggest that the observed alterations are not specific to substance abuse (Figures S-6a to S-8b). The same analyses were also run to account for amphetamine use (amphetamine users versus controls; amphetamine non users versus controls), and achieved the same results.

Finally, direct comparisons of polysubstance users versus non users (subjects with only alcohol abuse) denoted negative results (See Figures S-6c, S-7c, and S-8c). The very circumscribed regions of significant tissue difference did not survive the permutation test. Moreover, these comparisons support the interpretation of our main findings were not due to substance abuse. Otherwise, we should have found hypotrophy (rather than hypertrophy) in the 20 subjects with polysubstance abuse compared to non users (Figure S-6c).

4. Discussion

4.1 Experimental findings

We compared the 3D morphology of the accumbens, caudate and putamen nuclei in a sample of criminal offenders with psychopathy. These subjects were not affected by disorders of the schizophrenia spectrum, and were compared to controls of same gender and similar age. These nuclei exhibited an atypical morphology, consisting in complex patterns of local enlargement and reduction. The different morphology of the nucleus accumbens was highly significant even after correcting for multiple comparisons.

Although a different experimental design (comparing non psychopathic offenders characterized by similar substance abuse and other sociodemographic features to psychopathic offenders) should be used to optimally address this issue, these effects did not seem to be attributable to substance abuse, based on our analyses stratifying by use of polysubstance or amphetamine. Non users of these substances showed in fact analogous effects of local enlargements and reductions, strong enough that could be detected in the subsample of only 6 non users, and that survived permutation test for the right accumbens.

Factor 3 of the PCL-R scale significantly correlated with caudate and putamen morphology. The smaller striatal volumes observed in the caudate and striatum of cocaine users (Barros-Loscertales et al., 2011) do not seem to affect the present findings, as patterns of local enlargements, analogous to previous studies of psychopathy, were found in our sample as well. Another recent study addressing the issue of substance abuse versus psychopathy (Schiffer et al., 2011) did not find specific alterations in the basal ganglia, nonetheless the lack of a proper sample of substance abusers with no psychopathy, specifically paired to our subjects also by other possible confounders keeps being the main limitation of our work: the association of abnormal striatal morphology with psychopathy requires replication in studies where psychopathic offenders are compared to non psychopathic offenders with similar psychiatric comorbidity, substance abuse, education, sociodemographic status and lifestyle.

In a previous VBM study on the same sample (Tiihonen et al., 2008), a hypotrophic area was detected at the rostro-ventral level of the basal ganglia, corresponding to the head of caudate and nucleus accumbens. This is consistent with the local distribution of the hypotrophic effects observed in this study (see Figure 4). Nonetheless, this study extended the VBM study by manually tracing these ROIs and reconstructing the full 3D shape of the accumbens, caudate and putamen. This maximized the localization accuracy for each subject, and boosted the sensitivity of local comparisons.

The present data are partly in line with previous findings of striatal enlargement in persons with psychopathy (Barkataki et al., 2006; Glenn et al., 2010) and among non psychopathic violent offenders (Schiffer et al., 2011). Indeed, when considering global basal ganglia, and particularly the caudate and putamen, controls had the lowest volumes also in our study. Nonetheless, a more complex pattern of alterations became apparent when examining local differences in the 3D reconstruction of the morphology of these nuclei. In particular, the segmentation of the nucleus accumbens showed a highly significant morphological discrepancy from controls, with a large anterior region of hypotrophy in psychopathy.

This feature was not observed in the voxel-based study by Schiffer and colleagues, who attributed the gray matter increase to the left accumbens and right caudate head. Nonetheless, their subjects scored very low on psychopathy measures: their violent subgroups had a mean of 9.3 and 12.8 at the PCL-R:SV (the Screening Version of the PCL-R); this scale has a score range of 0–24, and the cut-off for the diagnosis of psychopathy is a score equal or higher than 18. Therefore, it can be concluded that their study population was markedly different from ours. Moreover, VBM may not offer optimal sensitivity or power to analyze small subcortical regions-of-interest, such as the accumbens or the caudate head. Despite the benefits of being efficient to use, VBM may miss more complex patterns of local alterations that may be captured by surface-based anatomical modeling techniques.

Our findings are in line with functional and clinical data in psychopathy, and with theories of limbic involvement in psychopathy (Craig et al., 2009; Kiehl, 2006; Raine et al., 2010), relating cerebral function and morphology to specific features of adaptive behavior. Hypo-function of the ventral striatum (Kiehl et al., 2001), and a biased responsivity to reward stimuli in the accumbens (Buckholtz et al., 2010) have been detected using functional neuroimaging. Recently, hyper-responsivity to mesolimbic dopamine in the positive reward anticipation phase, with lack of feedback signal, has been reported as specifically associated with the impulsive-antisocial trait in psychopathy (Buckholtz et al., 2010). The absence of any feedback-related activity in the accumbens - and in the most closely connected limbic structures carrying out reversal learning - is consistent with a biased sensitivity to the positive reward anticipation in psychopathy. The other key adaptive function of the accumbens, consisting in signaling salience of stimuli (Horvitz, 2000; Jensen et al., 2003; Zink, Pagnoni, Martin, Dhamala, & Berns, 2003) may be less effective. The prevailing anticipation of positive reward may explain the typical parasitic/predatory strategy of individuals with psychopathy, who disregard the possible negative consequences of their behavior, as well as the negative consequences of the substance abuse typically observed in this condition (Buckholtz et al., 2010). Closely connected with the above, the function of reversal learning is defective in psychopathy (Budhani, Richell, & Blair, 2006; Mitchell et al., 2006) – this is another key function carried out by the nucleus accumbens in a circuit containing the amygdala and orbitrofrontal cortex (Kringelbach & Rolls, 2004). Reversal learning is the ability to overwrite previously learned strategies as the environment changes. If an action led to success in the past, but would fail in the present situation, the feedback about the negative output of one’s own action allows the individual to cancel the previous conditioning, and learn that in the new situation a different course of action needs to be programmed. This will eventually be reinforced and may thus condition subsequent decision making. The deficit in reversal learning observed in psychopathy (Budhani et al., 2006; Mitchell et al., 2006) explains why these individuals are unable to capitalize on prior experience - particularly on negative experience - to update the value of reinforcement learnings.

The augmented sensitivity of the accumbens to mesolimbic dopamine during positive reward anticipation (Buckholtz et al., 2010) may appear to contrast with the wide tissue deficit observed in this study. However, it should be underlined that, as for the accumbens, the map of alterations consisted of both reductions and enlargements (Figures S-1a-S1-b). Tissue reduction is in line with deficits in a number of other functions ascribed to the nucleus accumbens (signaling salience for non-positive or non-reward stimuli, providing feedback about the reward obtained, reverse previously learned values of reinforcements). To interpret the complex enlargement and reduction patterns observed in this study, further investigations are needed to elucidate the complex mechanisms of biased hyper-responsivity and relate them to the pattern of intra- and extra-striatal connectivity in psychopathy. Even so, the abnormal morphology of the structures most closely connected to the nucleus accumbens, such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Boccardi et al., 2011; de Oliveira-Souza et al., 2008; Tiihonen et al., 2008) and the amygdale (Boccardi et al., 2011; Yang, Raine, Narr et al., 2009), in psychopathy is consistent with the involvement of the whole functional circuit known to allow plastic, flexible and responsive adaptation to the environment (Floresco, Zhang, & Enomoto, 2009; Haber & Knutson, 2010; Kringelbach & Rolls, 2004). Indeed, this same sample (Boccardi et al., 2011) showed up to 30% hypotrophy specifically in the basolateral nucleus of the amygdale (Boccardi et al., 2011), and this alteration was detected also in another independent sample (Yang, Raine, Narr et al., 2009). The basolateral nucleus of the amygdala is specifically connected to the nucleus accumbens and to the ventral orbitofrontal cortex (LeDoux, 2007), in a circuit serving the function of reversal learning, allowing a person to flexibly adapt to the changing environment (Kringelbach & Rolls, 2004; LeDoux, 2007).

Our analyses did not provide clear patterns of tissue correlation with psychopathy severity. This may possibly be due to the fact that the range of PCL-R scores in our subjects was rather restricted, covering only the ranges of medium and high psychopathy. Alternatively, the reason could be that correlation with severity may not lie on the same continuum of differences in morphology from controls. Indeed, this possibility is consistent with the fact that the R maps did not overlap with the maps of differences from controls. Instead, Factor 3, measuring the lifestyle trait, correlated significantly with the morphology of the caudate and putamen. The key items of impulsivity and sensation seeking, measured within this PCL-R sub-factor, may relate to the described abnormal response to dopamine demonstrated in psychopathy (Buckholtz et al., 2010), although we did not observe this correlation in the accumbens.

4.2 Study limitations

In this work, great care was taken to recruit subjects with an accurate diagnosis of psychopathy, excluding disorders of the schizophrenia spectrum. Still, the main limitation is that we lacked a comparison group matched on most confounding variables known to be associated to brain morphology. A much finer experimental design, matching subjects by IQ, lifestyle, education, drug abuse, criminality and socioeconomic status, personality disorders or comorbidity, and possibly with exclusion of other major psychiatric conditions such as disorders of the schizophrenia spectrum, would require a much larger availability of patients than has been usually possible to date. Nonetheless replication of our data on studies of this kind is required to draw firmer conclusions on the possible association of psychopathy with specific cerebral morphology features.

Similarly, a larger sample size, providing a wider range of variability in the PCL-R scores, besides better characterized controls, and non psychopathic controls displaying the same interfering conditions (criminality, personality disorders, substance abuse) are necessary.

Finally, extensive (6 nuclei for subject) and accurate ROIs manual tracings were carried out based on a newly defined optimized protocol for the manual segmentation of the basal ganglia. (ICC) for manual segmentations were very high, nonetheless a more powerful magnetic field strength than the 1T may lead to even higher figures, increasing the power of the experiment, especially for some posterior boundaries of the putamen where the borders are less clear-cut. 3T images may also improve the visualization of the boundaries of the globus pallidus, for which we were not able to achieve good ICC on our 1T images.

4.3 Interpretation of neuroimaging findings

Previous work on the same psychopathy sample found atypical morphological features of a number of brain structures. In the literature, brain differences in psychopathy are usually interpreted as associated to deficit in the psychological functions leading to the antisocial conduct observed in these subjects. In this case, the hypotrophy of the nucleus accumbens can definitely account for the known unresponsiveness of psychopathic offenders to correctional treatments. On the other side, regions with less gray matter can not be considered to be atrophic in these subjects: in our study these differences are not caused by trauma or degeneration, or other neurological disorders in the brain. These are just the anatomical differences that accompany psychopathic behavior, and that can be detected since young age in juveniles with conduct disorder (De Brito et al., 2009). Moreover, since we also find hypertrophy in many cerebral regions, we may also describe our data as characterizing an alternative cerebral morphology, rather than a disease that has been damaging the brain.

Indeed, in this, as well as in previous work, we find a complex pattern including both reduction and enlargement effects. The main finding of the present paper consists indeed in a severe hypotrophy of the nucleus accumbens, that we interpret as closely related to the known less effective reversal learning that characterizes the neuropsychological performance and the clinical manifestation observed in psychopathy. Nonetheless, we propose that this kind of findings, together with the observation that hypertrophic regions are also observed in this and other investigations of psychopathy, may also be considered within a different and wider frame. Consistent with Darwin’s theory natural evolution (Darwin, 1872) and following genetics theorizations, the different brain morphology of these subjects, and the different lifestyle and behavior, actually lead to a different pattern of costs and benefits in adapting to the environment, rather than just to disadvantages attributable to deficit or disease (Harris et al., 2007; Smith & Blumstein, 2008; Wilson, Clark, Coleman, & Dearstyne, 1994). This consideration purely relates to the biological level of examination of this condition, but, in our opinion, alternative interpretations like these should be kept in mind to avoid drawing premature conclusions about “normal” or “pathological” brain features. For sure, this kind of observation does not relate to the necessity of society to prosecute the aberrant behavior of psychopathic individuals. Though, the influence that neuroscience is exerting on a large number of juridical issues is rapidly increasing over time (Aronson, 2009; Gazzaniga 2011), and we envision the danger that premature and limited interpretations of “objective” scientific findings (Weisberg, Keil, Goodstein, Rawson, & Gray, 2008) might misleadingly provide further support to improper conclusions (Morse, 2006), with relevant consequences on society. We believe that ambiguities and possible alternative interpretations of the same objective findings should be made explicit, to advice regarding possible misuse of such data, as well as to generate possibly fruitful scientific investigation for future studies.

A further comment relates the recent use of neuroscientific findings of this kind, to find whether an individual charged with an offence may be attributed a diagnosis of a disease shown to be associated with some cerebral features. In this study, and in many others of this kind, we found an association of cerebral features with psychopathy, but we did not compute the sensitivity and specificity of such features, in identifying psychopathy in the normal population, nor versus other non-psychopathic samples of offenders. Therefore, the use of this kind of data to “diagnose” psychopathy in individual subjects is not warranted to date.

5. Conclusions

This study detects a peculiar striatal morphology, characterized by severe hypotrophy of the nucleus accumbens, in offenders with psychopathy. Replication is required due to many limitations of the study, anyway this finding is consistent with the clinical and neuropsychological features of psychopathy, as well as the known unresponsiveness to treatment or correction of these subjects.

Psychobiological correlates of psychopathy point to the involvement of the paralimbic network, a set of cerebral structures connecting emotional information to the structures processing cognitive information and controlling behaviour. Anyway, scientific investigations did not achieve definitive conclusions about this condition yet, and the transfer of this kind of data to everyday practice, especially at the juridical level, may not straightforward for a number of reasons, and should be considered as premature to date.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

P.T. is supported in part by NIH grants EB008281, RR013642, and AG020098.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and should not be interpreted as having been endorsed by the National Institutes of Health.

This work was also supported by AFaR (Associazione Fatebenefratelli per la Ricerca).

We thank Enrica Cavedo, who served as reference for the computation of the inter-rater ICC values for the examined nuclei.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors had any interest competing with the present work.

References

- Aronson JD. Neuroscience and juvenile justice. Akron Law Review. 2009;42:917–930. [Google Scholar]

- Barkataki I, Kumari V, Das M, Taylor P, Sharma T. Volumetric structural brain abnormalities in men with schizophrenia or antisocial personality disorder. Behav Brain Res. 2006;169(2):239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros-Loscertales A, Garavan H, Bustamante JC, Ventura-Campos N, Llopis JJ, Belloch V, et al. Reduced striatal volume in cocainedependent patients. NeuroImage. 2011;56(3):1021–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccardi M, Frisoni GB, Hare RD, Cavedo E, Najt P, Pievani M, et al. Cortex and amygdala morphology in psychopathy. Psychiatry Research. 2011;193(2):85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccardi M, Ganzola R, Rossi R, Sabattoli F, Laakso MP, Repo-Tiihonen E, et al. Abnormal hippocampal shape in offenders with psychopathy. Human Brain Mapping. 2010;31(3):438–447. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckholtz JW, Treadway MT, Cowan RL, Woodward ND, Benning SD, Li R, et al. Mesolimbic dopamine reward system hypersensitivity in individuals with psychopathic traits. Nature Neuroscience. 2010;13(4):419–421. doi: 10.1038/nn.2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budhani S, Richell RA, Blair RJ. Impaired reversal but intact acquisition: Probabilistic response reversal deficits in adult individuals with psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(3):552–558. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig MC, Catani M, Deeley Q, Latham R, Daly E, Kanaan R, et al. Altered connections on the road to psychopathy. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14(10):946–953. 907. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. The origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. London: John Murray; 1872. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Brito SA, Mechelli A, Wilke M, Laurens KR, Jones AP, Barker GJ, et al. Size matters: Increased grey matter in boys with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. Brain : A Journal of Neurology. 2009;132(Pt 4):843–852. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira-Souza R, Hare RD, Bramati IE, Garrido GJ, Azevedo Ignacio F, Tovar-Moll F, Moll J. Psychopathy as a disorder of the moral brain: Fronto-temporo-limbic grey matter reductions demonstrated by voxel-based morphometry. NeuroImage. 2008;40(3):1202–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O, Morrell MJ, Vogt BA. Contributions of anterior cingulate cortex to behaviour. Brain. 1995;118:279–306. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.1.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, Zhang Y, Enomoto T. Neural circuits subserving behavioral flexibility and their relevance to schizophrenia. Behavioural Brain Research. 2009;204(2):396–409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frackowiak RSJ, Friston KJ, Frith C, Dolan R, Friston KJ, Price CJ, Zeki S, Ashburner J, Penny WD. Human Brain Function. 2nd edition. San Diego (CA): Academic Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi S, Testa C, Boccardi M, Bresciani L, Benussi L, Ghidoni R, Beltramello A, Bonetti M, Bono G, Falini A, Magnani G, Minonzio G, Piovan E, Binetti G, Frisoni GB. The Italian Brain Normative Archive of structural MR scans: norms for medial temporal atrophy and white matter lesions. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009;21(4–5):266–276. doi: 10.1007/BF03324915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaniga MS. Neuroscience in the courtroom. Sci Am. 2011;304(4):54–59. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0411-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage. 2002;15:870–878. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn AL, Raine A, Yaralian PS, Yang Y. Increased volume of the striatum in psychopathic individuals. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning-Dixon FM, Head D, McQuain J, Acker JD, Raz N. Differential aging of the human striatum: A prospective MR imaging study. AJNR.American Journal of Neuroradiology. 1998;19(8):1501–1507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN, Knutson B. The reward circuit: Linking primate anatomy and human imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology : Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):4–26. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. The hare psychopathy checklist-revised. II ed. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Syst.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, Neumann CS. Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:217–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GT, Rice ME, Hilton NZ, Lalumiere ML, Quinsey VL. Coercive and precocious sexuality as a fundamental aspect of psychopathy. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21(1):1–27. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokama H, Shenton ME, Nestor PG, Kikinis R, Levitt JJ, Metcalf D, et al. Caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus volume in schizophrenia: A quantitative MRI study. Psychiatry Research. 1995;61(4):209–229. doi: 10.1016/0925-4927(95)02729-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Y, Benjamini Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med. 1990;9:811–818. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz JC. Mesolimbocortical and nigrostriatal dopamine responses to salient non-reward events. Neuroscience. 2000;96(4):651–656. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J, McIntosh AR, Crawley AP, Mikulis DJ, Remington G, Kapur S. Direct activation of the ventral striatum in anticipation of aversive stimuli. Neuron. 2003;40(6):1251–1257. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00724-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehl KA. A cognitive neuroscience perspective on psychopathy: Evidence for paralimbic system dysfunction. Psychiatry Res. 2006;142(2–3):107–128. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehl KA, Smith AM, Hare RD, Mendrek A, Forster BB, Brink J, Liddle PF. Limbic abnormalities in affective processing by criminal psychopaths as revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50(9):677–684. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigs M, Baskin-Sommers A, Zeier J, Newman JP. Investigating the neural correlates of psychopathy: A critical review. Molecular Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach ML, Rolls ET. The functional neuroanatomy of the human orbitofrontal cortex: Evidence from neuroimaging and neuropsychology. Progress in Neurobiology. 2004;72(5):341–372. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux J. The amygdala. Current Biology : CB. 2007;17(20):R868–R874. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris N, Meyer JW, Bates JF, Yeterian EH, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS. MRI-based topographic parcellation of human cerebral white matter and nuclei II. rationale and applications with systematics of cerebral connectivity. NeuroImage. 1999;9(1):18–45. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DG, Fine C, Richell RA, Newman C, Lumsden J, Blair KS, Blair RJ. Instrumental learning and relearning in individuals with psychopathy and in patients with lesions involving the amygdala or orbitofrontal cortex. Neuropsychology. 2006;20(3):280–289. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.20.3.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse SJ. Brain overclaim syndrome and criminal responsibility: A diagnostic note. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law. 2006;3:397. [Google Scholar]

- Muller JL, Ganssbauer S, Sommer M, Dohnel K, Weber T, Schmidt-Wilcke T, Hajak G. Gray matter changes in right superior temporal gyrus in criminal psychopaths. evidence from voxel-based morphometry. Psychiatry Research. 2008;163(3):213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan VM, Narr KL, Kumari V, Woods RP, Thompson PM, Toga AW, Sharma T. Regional cortical thinning in subjects with violent antisocial personality disorder or schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1418–1427. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narr KL, Thompson PM, Szeszko P, Robinson D, Jang S, Woods RP, et al. Regional specificity of hippocampal volume reductions in first-episode schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 2004;21(4):1563–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Lee L, Yang Y, Colletti P. Neurodevelopmental marker for limbic maldevelopment in antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science. 2010;197(3):186–192. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.078485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer B, Muller BW, Scherbaum N, Hodgins S, Forsting M, Wiltfang J, et al. Disentangling structural brain alterations associated with violent behavior from those associated with substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68(10):1039–1049. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BR, Blumstein DT. Fitness consequences of personality: A meta-analysis. Behavioral Ecology: Official Journal of the International Society for Behavioral Ecology. 2008;19(2):448–455. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, De Zubicaray GI, Janke AL, Rose SE, Semple J, et al. Mapping hippocampal and ventricular change in Alzheimer's disease. NeuroImage. 2004;22(4):1754–1766. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, de Zubicaray G, Janke AL, Rose SE, Semple J, et al. Dynamics of gray matter loss in alzheimer's disease. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23(3):994–1005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00994.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Schwartz C, Toga AW. High-resolution random mesh algorithms for creating a probabilistic 3D surface atlas of the human brain. NeuroImage. 1996;3(1):19–34. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiihonen J, Rossi R, Laakso MP, Hodgins S, Testa C, Perez J, et al. Brain anatomy of persistent violent offenders: More rather than less. Psychiatry Research. 2008;163(3):201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt BA, Finch DM, Olson CR. Functional heterogeneity in cingulate cortex: The anterior executive and posterior evaluative regions. Cereb Cortex. 1992;2(6):435–443. doi: 10.1093/cercor/2.6.435-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg DS, Keil FC, Goodstein J, Rawson E, Gray JR. The seductive allure of neuroscience explanations. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20(3):470–477. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DS, Clark AB, Coleman K, Dearstyne T. Shyness and boldness in humans and other animals. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 1994;9(11):442–446. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Raine A, Colletti P, Toga AW, Narr KL. Abnormal temporal and prefrontal cortical gray matter thinning in psychopaths. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14(6):561–562. 555. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Raine A, Narr KL, Colletti P, Toga AW. Localization of deformations within the amygdala in individuals with psychopathy. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66(9):986–994. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink CF, Pagnoni G, Martin ME, Dhamala M, Berns GS. Human striatal response to salient nonrewarding stimuli. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23(22):8092–8097. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-22-08092.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.