To the Editor:

Asthma, a leading cause of obstructive lung disease, is characterized by inflammation, mucus secretion, and remodeling of peribronchiolar connective tissue. These changes plus goblet cell metaplasia, smooth muscle hyperplasia, airway thickening, and eosinophil recruitment are regulated by or are a consequence of various cytokines, including IL-4, -13, -5, -9, and more recently -17 (1–8).

Type V collagen (col[V]), a minor collagen, is intercalated within fibrils of type I collagen, the major lung collagen (9). Due to its location, col(V) is considered a sequestered antigen not normally exposed to the immune system. However, interstitial remodeling leads to col(V) exposure, and results in a cryptic antigen becoming a target of the immune response. Indeed, we reported that anti-col(V) immunity developed in the pathogenesis of lung transplant–associated obliterative bronchiolitis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which are two disorders characterized by extensive interstitial remodeling (10, 11). Studies showing that immune responses to col(V) are involved in disease pathogenesis suggest that immune tolerance to col(V) may be protective of tissue injury. Indeed, col(V)-induced tolerance prevented acute lung allograft rejection and obliterative bronchiolitis (12–14), as well as bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis (15).

Because asthma is a disease that may involve interstitial remodeling, we hypothesized that clinical asthma is associated with anti-col(V) immunity and that col(V)-induced tolerance may limit the asthmatic response. Examination of serum from normal subjects and patients with asthma in the current study show higher levels of systemic anti-col(V) antibodies in individuals with asthma, and overexpression of interstitial col(V) in fatal asthma. col(V)-induced tolerance down-regulated ovalbumin (OVA)-induced airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) by reduction of airway smooth muscle contraction.

Methods

Methods are available in the online supplement.

Results

Anti-col(V) antibodies and col(V) expression in asthma.

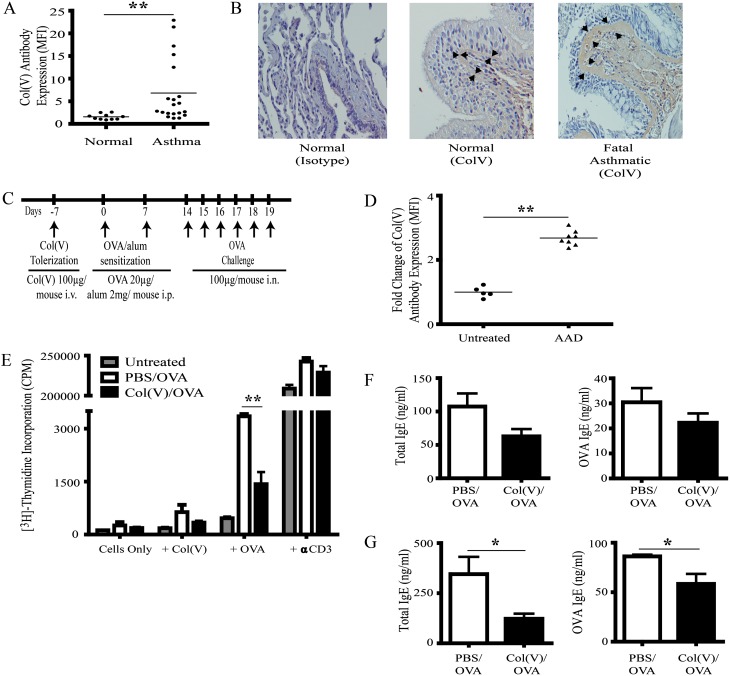

We first determined if clinical asthma was associated with the presence of anti-col(V) antibodies. The study population is described in Table 1. Compared with healthy normal volunteers, individuals with asthma had significantly higher levels of serum anti-col(V) antibodies (P < 0.001) (Figure 1A). To determine if col(V) is highly expressed in the asthmatic lung, col(V) expression was assessed in a lung section from a patient who succumbed to an asthmatic episode. As expected in the normal lung, some col(V) staining was present in the subepithelial tissues and basement membrane, and stained at low levels in adjacent peribronchiolar tissues. In contrast, col(V) staining was increased in the thickened basement membrane and adjacent tissues in fatal asthma (Figure 1B).

TABLE 1.

PATIENT DEMOGRAPHIC DATA

| Variable | Patients with asthma (mean ± SD) |

| Age, yr | 41.14 ± 14.69 |

| Male, n (%) | 8 (50) |

| FEV1/FVC | 73.11 ± 9.03 |

| FEV1 | 91.45 ± 14.32 |

| FVC | 102 ± 12.69 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Percents are numerators divided by the total number of subjects.

Figure 1.

Detection of systemic anti–type V collagen (col[V]) antibodies in clinical asthma and allergic airway disease. (A) Serum was collected from 20 clinically defined individuals with asthma and 10 nonsmoking individuals without asthma and assayed by flow cytometry to detect IgG antibodies (Abs) bound to col(V)-coated beads. Data are shown as mean fluorescent intensity (MFI). **P < 0.01 using a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test, significantly different from normal individuals. (B) Lung sections from a patient who succumbed to an asthmatic episode were embedded in paraffin and stained with anti-col(V) antibodies (original magnification, ×40). Arrows point to expression of col(V) in subepithelium. (C) Balb/c mice were exposed to intravenous col(V) 7 days before the indicated time points of ovalbumin (OVA)/alum sensitization and OVA challenge. (D) Serum was collected from five untreated and eight airway hyperresponsiveness mice and assayed by flow cytometry to detect IgG Abs bound to col(V)-coated beads. Data are shown as MFI. **P < 0.01 using a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test, significantly different from untreated animals. (E) Total cells from the mediastinal lymph nodes of untreated or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)- or col(v)-treated animals were cultured with irradiated splenocytes (3,000 rad) in the presence of OVA (100 μg/[1 × 106 cells]), col(V) (40 μg), or anti-CD3 Ab (0.5 μg/ml) for 72 hours. Cellular proliferation was measured by 3H thymidine incorporation. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 5 pooled animals and is representative of two independent experiments. **P < 0.01 using one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test. (F) Total and OVA-specific IgE levels were quantified in the serum of OVA-sensitized and challenged PBS and col(V) animals by ELISA. (G) Total and OVA-specific IgE levels were quantified in BAL fluid of OVA-sensitized and challenged PBS and col(V) animals by ELISA. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of five mice in each group. *P < 0.05 using two-tailed Student’s t test. AAD = allergic airway disease; CPM = counts per minute.

Induction of col(V) tolerance.

To determine if allergic airway disease (AAD) is also associated with anti-col(V) antibodies, we measured anti-col(V) antibodies in untreated mice and mice after OVA-induced AAD. In parallel studies, col(V) tolerance was induced by a single intravenous injection (100 μg) prior to OVA/alum as reported in the Methods in the online supplement and shown in Figure 1C. Compared with untreated mice or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-treated controls, AAD resulted in development of anti-col(V) antibodies (Figure 1D). To determine if OVA-induced AAD resulted in anti-col(V) cellular immune responses, mediastinal lymph node cells were isolated and cultured in the presence of OVA or col(V). As expected, OVA sensitization alone resulted in brisk OVA-induced proliferation (P < 0.01) (Figure 1E). Consistent with detection of anti-col(V) antibodies, OVA-sensitized mice developed a trend toward higher proliferation in response to col(V) (Figure 1E). Notably, col(V) treatment significantly suppressed OVA-induced proliferation, indicating that col(V) administration induced tolerance (P < 0.01) (Figure 1E). Local and systemic humoral responses were studied; the levels of total and OVA-specific IgE were assessed in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) of treated animals. Compared with PBS-treated controls, total and OVA-specific IgE levels were unchanged in the serum of col(V)-tolerized mice (Figure 1F). In contrast, col(V)-induced tolerance resulted in significant reductions in total and OVA-specific IgE antibodies in BAL fluid (P < 0.05) (Figure 1G). Collectively, these data indicate that OVA-induced AHR results in anti-col(V) immunity, and col(V)-induced tolerance abrogates local OVA-induced cellular and humoral immune responses.

col(V)-induced tolerance down-regulated AHR.

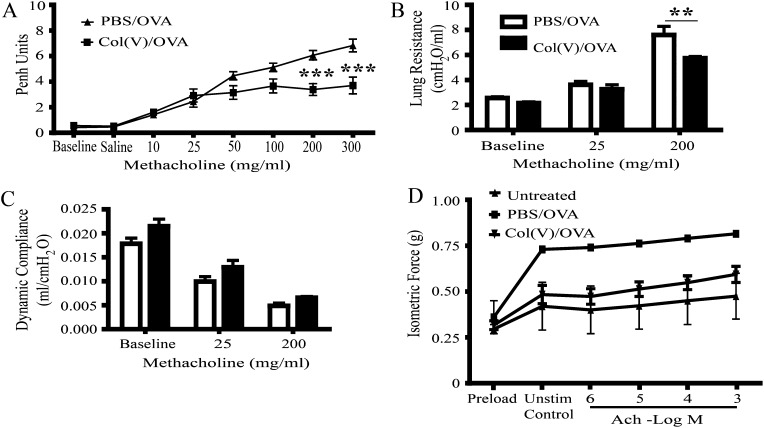

To study the effects of col(V)-induced tolerance on AHR, we assessed lung function both by noninvasive (enhanced pause [Penh]) and invasive methods of measuring airway resistance and lung compliance. As expected, OVA sensitization and challenge resulted in dose-dependent increases in Penh in response to methacholine in PBS-treated (control) mice (Figure 2A). In contrast, Penh gradually increased in col(V)-tolerized mice at low methacholine concentrations, then plateaued at higher concentrations, which were significantly lower than PBS-treated controls (P < 0.001) (Figure 2A). Resistance, a measure of airway obstruction, was also significantly reduced in col(V)-tolerized mice compared with controls at the highest methacholine concentrations (P < 0.01) (Figure 2B). There was no change in compliance in the col(V)-tolerized group compared with the PBS group (Figure 2C). Consistent with data showing less airway resistance, airway smooth muscle contractile force in response to acetylcholine stimulation was decreased in mice tolerized with col(V) when compared with PBS-treated controls (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

The effect of type V collagen (col[V])-induced tolerance on allergen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR). AHR was measured 24 hours after the final intranasal challenge. (A) Twenty-four hours after the final challenge, AHR to aerosolized methacholine was measured in conscious mice using unrestrained, whole-body plethysmography (Penh). The mice were first treated with saline and then exposed to increasing doses of methacholine from 10 to 300 mg/ml. Methacholine was nebulized for 2 minutes; readings were then measured for 5 minutes after nebulization. (B and C) Lung resistance and dynamic compliance were measured in anesthetized and intubated mice, delivering nebulized saline and increasing doses of methacholine, from 10 to 200 mg/ml. (D) Smooth muscle contractile forces to Ach were measured in the tracheas of treated mice using 10−9 to 10−3 M acetylcholine from two to three mice per group. Data represent mean ± SEM of five to six mice per group for A–C. For D, data are representative of two to three animals per group with similar results. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, significantly different from PBS using two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test. Ach = acetylcholine; Penh = enhanced pause.

Discussion

We previously reported that diseases associated with lung remodeling may result in col(V) exposure and generation of anti-col(V) cellular and humoral responses (16). Because asthma may also involve lung remodeling, in the current study we hypothesized that asthma may lead to anti-col(V) immunity. The current data show that anti-col(V) antibodies develop in clinical asthma and that col(V), normally sequestered, is highly expressed in the lung during fatal asthma. Murine AAD also results in anti-col(V) antibodies, and col(V)-induced tolerance decreased AHR and smooth muscle contraction.

The presence of circulating anti-col(V) antibodies in clinical asthma is consistent with our prior studies showing that lung remodeling and inflammation may be associated with loss of self-tolerance to col(V) and development of anti-col(V) immunity (11). Indeed, lung allograft rejection, both acute and chronic, is associated with extensive lung remodeling and development of anti-col(V) cellular and humoral immunity (17). We observed similar findings in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (18). Although lung remodeling is a well-known complication of asthma, to the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to report that immune responses to the autoantigen col(V) may have a role in asthma pathogenesis. The role of autoimmunity in asthma pathogenesis has been the subject of debate without identification of a specific antigen. However, current data suggest that col(V) may be a novel target of the immune response in asthma. These data could also suggest how disorders that may induce lung inflammation, such as viral infections, may contribute to asthma by causing lung remodeling and subsequent exposure of col(V).

There are some limitations to our current study. The dynamic range of the flow-based anti-col(V) assay cannot be determined in absolute col(V) concentrations (e.g., milligrams per deciliter). Although we have shown that col(V)-induced tolerance decreases airway smooth muscle contraction and decreases antigen-induced T- and B-cell activity, the exact mechanism by which tolerance induced these changes has not been specifically elucidated. Another question involves how col(V) is able to mediate tolerance to an unrelated antigen, that of OVA. Previous studies have shown that col(V)-induced tolerance to unrelated antigens, such as alloantigens in lung transplantation, is mediated by linked suppression and via induction of regulatory T cells (19). The further determination and delineation of the mechanism by which col(V)-induced tolerance alters AAD represent new studies that will be performed over the next several years.

The current study reports a link between a self-protein and the pathogenesis of asthma. Our current model involves the induction of AAD and the increase of circulating col(V) antibodies, which may lead to the progression of the pathogenesis of the disease. The current data suggest that col(v)-induced tolerance down-regulates AHR associated with AAD by decreasing tracheal smooth muscle contraction. These data demonstrate the identification of one of the first linkages between a self-protein and asthma. These data open the door and point to a possible use for col(V) in the treatment of allergic airway disease.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Conception and design: J.M.L. and D.S.W. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: J.M.L., S.S., P.M., E.A.M., A.J.F., W.Z., M.H.K., M.F.B., and D.S.W. Drafting and revision of the manuscript: J.M.L., S.S., P.M., R.G.P., S.G., S.J.G., S.E.W., M.H.K., and D.S.W.

Supported by the Indiana University Initiative for Maximizing Graduate Student Diversity (funded by NIH grant R25 GM079657) to J.M.L. and NIH grant R01HL067177 to D.S.W.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Cohn L, Tepper JS, Bottomly K. Cutting edge: IL-4-independent induction of airway hyperresponsiveness by Th2, but not Th1, cells. J Immunol 1998;161:3813–3816 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wills-Karp M, Luyimbazi J, Xu X, Schofield B, Neben TY, Karp CL, Donaldson DD. Interleukin-13: central mediator of allergic asthma. Science 1998;282:2258–2261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grünig G, Warnock M, Wakil AE, Venkayya R, Brombacher F, Rennick DM, Sheppard D, Mohrs M, Donaldson DD, Locksley RM, et al. Requirement for IL-13 independently of IL-4 in experimental asthma. Science 1998;282:2261–2263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trifilieff A, Fujitani Y, Coyle AJ, Kopf M, Bertrand C. IL-5 deficiency abolishes aspects of airway remodelling in a murine model of lung inflammation. Clin Exp Allergy 2001;31:934–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster PS, Hogan SP, Ramsay AJ, Matthaei KI, Young IG. Interleukin 5 deficiency abolishes eosinophilia, airways hyperreactivity, and lung damage in a mouse asthma model. J Exp Med 1996;183:195–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLane MP, Haczku A, van de Rijn M, Weiss C, Ferrante V, MacDonald D, Renauld J-C, Nicolaides NC, Holroyd KJ, Levitt RC. Interleukin-9 promotes allergen-induced eosinophilic inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in transgenic mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1998;19:713–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laan M, Cui Z-H, Hoshino H, Lötvall J, Sjöstrand M, Gruenert DC, Skoogh B-E, Lindén A. Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via C-X-C chemokine release in the airways. J Immunol 1999;162:2347–2352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson RH, Whitehead GS, Nakano H, Free ME, Kolls JK, Cook DN. Allergic sensitization through the airway primes Th17-dependent neutrophilia and airway hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:720–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linsenmayer TF, Gibney E, Igoe F, Gordon MK, Fitch JM, Fessler LI, Birk DE. Type V collagen: molecular structure and fibrillar organization of the chicken alpha 1(V) NH2-terminal domain, a putative regulator of corneal fibrillogenesis. J Cell Biol 1993;121:1181–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mares DC, Heidler KM, Smith GN, Jr, Cummings OW, Harris ER, Foresman B, Wilkes DS. Type V collagen modulates alloantigen-induced pathology and immunology in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000;23:62–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haque MA, Mizobuchi T, Yasufuku K, Fujisawa T, Brutkiewicz RR, Zheng Y, Woods K, Smith GN, Cummings OW, Heidler KM, et al. Evidence for immune responses to a self-antigen in lung transplantation: role of type V collagen-specific T cells in the pathogenesis of lung allograft rejection. J Immunol 2002;169:1542–1549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasufuku K, Heidler KM, O'Donnell PW, Smith GN, Jr, Cummings OW, Foresman BH, Fujisawa T, Wilkes DS. Oral tolerance induction by type V collagen downregulates lung allograft rejection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2001;25:26–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasufuku K, Heidler KM, Woods KA, Smith GNJ, Cummings OW, Fujisawa T, Wilkes DS. Prevention of bronchiolitis obliterans in rat lung allografts by type V collagen-induced oral tolerance. Transplantation 2002;73:500–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun RK, Molitor-Dart M, Wigfield C, Xiang Z, Fain SB, Jankowska-Gan E, Seroogy CM, Burlingham WJ, Wilkes DS, Brand DD, et al. Transfer of tolerance to collagen type V suppresses T-helper-cell-17 lymphocyte-mediated acute lung transplant rejection. Transplantation 2009;88:1341–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun RK, Martin A, Shah S, Iwashima M, Medina M, Byrne K, Sethupathi P, Wigfield CH, Brand DD, Love RB. Inhibition of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis through pre-treatment with collagen type V. J Heart Lung Transplant 2010;29:873–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkes DS, Heidler KM, Yasufuku K, Devito-Haynes L, Jankowska-Gan E, Meyer KC, Love RB, Burlingham WJ. Cell-mediated immunity to collagen V in lung transplant recipients: correlation with collagen V release into BAL fluid. J Heart Lung Transplant 2001;20:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwata T, Philipovskiy A, Fisher AJ, Presson RG, Chiyo M, Lee J, Mickler E, Smith GN, Petrache I, Brand DB, et al. Anti-type V collagen humoral immunity in lung transplant primary graft dysfunction. J Immunol 2008;181:5738–5747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bobadilla JL, Love RB, Jankowska-Gan E, Xu Q, Haynes LD, Braun RK, Hayney MS, Munoz del Rio A, Meyer K, Greenspan DS, et al. Th-17, monokines, collagen type V, and primary graft dysfunction in lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:660–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizobuchi T, Yasufuku K, Zheng Y, Haque MA, Heidler KM, Woods K, Smith GN, Cummings OW, Fujisawa T, Blum JS, et al. Differential expression of Smad7 transcripts identifies the CD4+CD45RChigh regulatory T cells that mediate type V collagen-induced tolerance to lung allografts. J Immunol 2003;171:1140–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.