Abstract

Optic perineuritis (OPN) is an uncommon inflammatory disorder of the optic nerve sheath. Most cases are idiopathic, though OPN can rarely occur as a manifestation of vasculitic diseases. We describe the case of a 74-year-old Caucasian man presenting with diplopia and bilateral visual loss. A brain MRI showed bilateral OPN without involvement of other structures. All the tests performed to investigate OPN's aetiology showed negative results. Considering clinical presentation and neuroimaging findings, a diagnosis of bilateral idiopathic OPN was made. Treatment with intravenous high-dose steroid was administered. Four weeks after admission, the steroid therapy was interrupted because of Listeria monocytogenes invasive infection. After steroid treatment withdrawal, the patient developed jaw claudication and bilateral skin necrosis of the temporal region, clinical features that are highly specific for giant cell arteritis (GCA). On this basis, a diagnosis of bilateral OPN secondary to GCA was made.

Background

Optic perineuritis (OPN) is a very rare form of orbital inflammatory disease involving the optic nerve sheath.1 Most cases are idiopathic; however, OPN can seldom be the manifestation of an inflammatory disorder like giant cell arteritis (GCA).2 We report the case of a 74-year-old Caucasian man, presenting with diplopia and bilateral OPN, treated with high-dose steroid therapy and complicated by Listeria monocytogenes (LM) sepsis and meningitis. After steroid treatment withdrawal, the patient developed jaw claudication and bilateral skin necrosis of the temporal region, clinical features that are highly specific for GCA and allowed the diagnosis of OPN secondary to GCA.

Case presentation

A 74-year-old Caucasian man experienced fluctuating diplopia for several days. For this reason, an ophthalmological evaluation and a brain MRI were performed, both resulting normal. About 7 days after the initial presentation, diplopia spontaneously resolved. Three weeks later, the patient was admitted to the hospital for subacute onset of blurred vision in the right eye, left eye central scotoma and unilateral headache in the left periorbital region. There were no symptoms of jaw claudication or polymyalgia rheumatica, fever, weight loss or asthenia. The patient's medical history was positive for arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and coronary artery disease.

General examination evidenced only mild bilateral thickening of the superficial temporal arteries, with reduced pulsation of the left side. Neurological examination revealed left eye mydriasis, bilateral absence of the pupillary reflexes, partial limitation of all the ocular movements and left eye ptosis. Visual acuity at presentation was 20/40 in the right eye and 20/32 in the left eye. Ophthalmoscopy demonstrated mild bilateral swelling of the optic disc. The remainder of the neurological examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory findings (with normal range) at admission were as follows: erythrocyte sedimentation rate 46 (<50 mm/h), C reactive protein 42.5 (<5 mg/l), white blood cells 7.63 (4–10.8×103 cell/mm3), red blood cells 3.76 (4.5–5.5×106 cell/mm3), haemoglobin 11.4 (14–18 g/dl), mean corpuscular volume 89.3 (82–94 fl), platelets: 328 (130–400×103 cell/mm3).

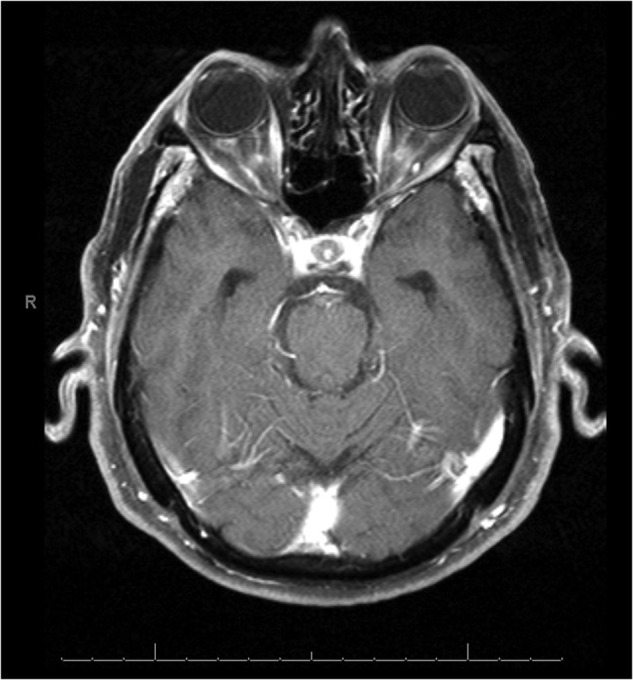

Brain MRI showed bilateral OPN (figure 1), without the involvement of other brain structures. To rule out causes of secondary OPN, the following tests were performed: serology for Treponema pallidum, herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, Toxoplasma gondii, HIV, hepatitis B virus infection, hepatitis C virus infection, Borrelia burgdorferi, quantiferon tuberculosis, ACE, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, C3, C4, CH50, extractable nuclear antigens antibodies Coombs test, cryoglobulins, B12 and folates. All these tests resulted normal. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was also within normal limits. Visual evoked potentials showed bilateral increased P-100 latency and reduction of the amplitude. Further, a bilateral temporal artery biopsy was performed, which showed negative results, thus not favouring the diagnosis of GCA.

Figure 1.

Axial T1-weighted MRI with gadolinium, showing bilateral enhancement of the optic nerve sheath.

Considering the clinical presentation, neuroimaging findings and negativity of all the other tests performed, a diagnosis of bilateral idiopathic OPN was carried out. One day after admission, the patient's visual acuity was 20/80 in both eyes.

A treatment with intravenous high-dose steroids was administered (methylprednisolone 1000 mg/day for 5 days). This therapy determined a rapid reduction followed by normalisation of the markers of inflammation. However, 2 days after the beginning of the corticosteroid treatment, visual acuity rapidly worsened to complete blindness. After 5 days of therapy, intravenous methylprednisolone was replaced with oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/day).

Four weeks after admission, the patient experienced high fever, somnolence and mild bilateral frontal headache. A brain CT scan (to rule out radiological signs of increased intracranial pressure) was negative, whereas CSF analysis was abnormal: glucose 36 mg/dl (normal range 50–100), proteins 85 mg/dl (normal range <45), cells 96/μl (normal range <4), with a predominance of polymorphonuclear cells. Suspecting a bacterial infection, an empiric antibiotic therapy with amikacine (1 g/day) and meropenem (3 g/day) was started.

CSF and blood cultures were positive for LM and a diagnosis of LM sepsis and meningitis was made. The oral steroid therapy was interrupted and an antibiotic treatment with ampicillin (12 g/day for 21 days) was administered. At the end of the antibiotic therapy, the patient was discharged with the following diagnosis: bilateral idiopathic OPN, LM sepsis and meningitis.

Five weeks after discharge, the patient complained about a severe left temporal headache and jaw claudication. General examination revealed mild bilateral skin necrosis of the temporal region, and the patient was admitted to the medical clinic. Oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/day) was restored, leading to a significant improvement of headache and jaw claudication. One week after admission, the patient was discharged with a diagnosis of GCA. To prevent further GCA complications, the high-dose oral steroid therapy was maintained for 4 weeks with subsequent gradual tapering.

Outcome and follow-up

Concerning the visual outcome of OPN, patients suffering from idiopathic OPN usually experience an excellent response to high-dose corticosteroid treatment when this therapy is rapidly started. Despite the prompt initiation of the intravenous corticosteroid therapy, our patient did not experience any visual improvement. It is very likely that the visual loss was not only determined by bilateral OPN but also related to arteritic ischaemia of the optic nerve head caused by GCA.

Discussion

OPN is an uncommon orbital inflammatory disorder that was first described by Edmunds and Lawford in 1883.3 Subjects suffering from OPN usually experience acute or subacute monocular visual loss, with eye pain exacerbated by ocular movement.1 Bilateral visual loss is uncommon. The optic nerve sheath is the main target of the inflammatory response, and reduction of visual acuity is secondary to optic nerve compression by the thickened optic nerve sheath. Diplopia and ptosis, owing to extraocular muscle inflammation, represent helpful features, suggesting the diagnosis of OPN.1 Optic disc oedema can be present. Pathological findings of OPN are perivascular lymphocytic infiltration of the optic nerve sheath, with a secondary marked fibrotic thickening.4 Brain MRI typically demonstrates pathological enhancement around the intraorbital optic nerve sheath, with or without involvement of the other orbital structures.5 The visual outcome of OPN is generally excellent, with dramatic improvement of vision and reduction of pain, when the treatment is rapidly administred.1

LM is a rare cause of illness in the general population; however, LM can be isolated from the stool of 5% of healthy adults,6 indicating that these individuals can be considered as ‘healthy carriers’ of LM. Corticosteroid treatment is a risk factor for developing LM invasive infection. Several clinical syndromes have been described for LM infection in adults. The most frequent are sepsis and central nervous system infections.7 8 Probably our patient was a healthy carrier of LM and the prolonged high-dose corticosteroid therapy promoted LM sepsis and meningitis.

Corticosteroid therapy withdrawal was followed by jaw claudication and bilateral skin necrosis in the temporal region. Jaw claudication is present in less than half of the patients with GCA, but it is highly specific for GCA.9

GCA is the most common primary systemic vasculitis in adults, affecting almost exclusively individuals older than 50 years of age.9

Headache is the most usual symptom of GCA, being present in about two-thirds of patients.10 Ophthalmological manifestations are common in GCA: in two large series, visual symptoms were present at the first manifestation of the disease in 26% and 50% of patients, respectively.11 12 Transient or permanent visual loss is the most common ocular manifestation. Diplopia is less frequent, but when present, it is suggestive of GCA.13

Our patient experienced fluctuating diplopia, spontaneously resolved, followed by the acute onset of headache and bilateral visual loss, with brain MRI evidence of bilateral OPN. Corticosteroid withdrawal determined the onset of jaw claudication and temporal skin necrosis. On this basis, a diagnosis of bilateral OPN secondary to GCA was made.

In our opinion, OPN preceded the onset of more usual symptoms of GCA, and pathognomonic clinical features of GCA became evident only when corticosteroid treatment was interrupted because of LM invasive infection. This case report illustrates that the clinical and radiological features of OPN may represent the first manifestation of GCA. OPN secondary to GCA may be an underestimated condition, because of the absence of common clinical features of GCA, due to early introduction of corticosteroid therapy for the treatment of OPN.

Learning points.

Optic perineuritis can rarely represent the first manifestation of giant cell arteritis (GCA).

Bilateral negativity of the temporal artery biopsy does not rule out the diagnosis of GCA.

Prolonged corticosteroid therapy represents an important risk factor for developing Listeria monocytogenes invasive infections.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Purvin V, Kawasaki A, Jacobson DM. Optic perineuritis: clinical and radiographic features. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:1299–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nassani S, Cocito L, Arcuri T, et al. Orbital pseudotumor as a presenting sign of temporal arteritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1995;13:367–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edumds W, Lawford JB. Examination of optic nerves from cases of amblyopia in diabetes. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK 1883;3:160–2 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Margo CE, Levy MH, Beck RW. Bilateral idiopathic inflammation of the optic nerve sheaths. Ophthalmology 1989;96:200–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fay AM, Kane SA, Kazim M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of optic perinuritis. J Neuroophthalmol 1997;17:247–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlech WF, 3rd, Lavigne PM, Bortolussi RA, et al. Epidemic listeriosis-evidence for transmission by food. N Engl J Med 1983;308:203–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clauss HE, Lorber B. Central nervous system infection with Listeria monocytogenes. Curr infect Dis Rep 2008;10:300–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mylonakis E, Hohmann EL, Calderwood SB. Central nervous system infection with Listeria monocytogenes: 33 years’ experience at a general hospital and review of 776 episodes from the literature. Medicine 1998;77:313–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawasaki A, Purvin V. Giant cell arteritis: an updated review. Acta Ophthalmol 2009;87:13–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salvarani C, Cantini F, Bolradi L, et al. Polymyalgia rheumatic and giant cell-arteritis. N Engl J Med 2002;347:261–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman B. Ocular manifestations of giant cell arteritis. Am J Ophthalmol 1998;125:509–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Garcia-Porrua C, Llorca J, et al. Visual manifestations of giant cell arteritis: trends and clinical spectrum in 161 patients. Medicine 2000;79:283–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smetana GW, Shmerling RH. Does this patient have temporal arteritis? JAMA 2002;287:92–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]