Abstract

Prescription medications are commonly used for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), however, there is little research regarding how the effect of medication is monitored across settings once prescribed. The present study addressed this issue for children with ASD in school by administering a questionnaire to teachers of students with ASD who were and were not being given medication. Specifically, the questionnaire assessed the teachers’ knowledge about whether the child was being given medication, and whether behavior changes or side effects were being communicated in any way to the child’s family and prescribing physician. The results showed that for children who were being given medication, fewer than half of the teachers reported knowing the child was being given medication. For those children who were not being given medication, only 53% of the teachers reported correct information for their students. Of the teachers who knew their students were being given medication, all reported that they were not conferring with the child’s prescribing physician regarding behavioral observations or side effects. Whether teachers are blind to the medication types and dosage the students are being given or not, some type of communication to physicians about the children’s behavior at school is important. Given the importance of monitoring medication for children with ASD, implications for system change, for professionals and for funding agencies are discussed.

Introduction

The prevalence of prescription medication use among children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is high and increasing (Aman, Lam, & Van Bourgondien, 2005; Green et al., 2006; Mandell et al., 2008; Oswald & Sonenklar, 2007; Witwer & Levavalier, 2005). It has been estimated that 30% to 60% of children with ASD are being given at least one prescription medication (Rosenberg et al., 2010) and that many medications are routinely prescribed (Leskovec, Rowles, & Findling, 2008; Posey, Sigler, Erickson, & McDougle, 2008) to treat a variety of behavioral symptoms (Coghill, 2003; Volkmar, Lord, Bailey, Schultz, & Klin, 2004; Volkmar, Weisner, & Westphal, 2006; Williamson & Martin, 2010). Once these children begin taking prescription medication, they are likely to continue to take medication for at least several years (Coghill, 2003; Ebensen, Greenberg, Seltzer, & Aman, 2009) and prescription medication costs for children with ASD are significantly more than for children in general (Liptak, Stuart, & Auinger, 2006). Thus, the issue of monitoring benefits and side-effects over time is important and research is needed to evaluate the coordination of monitoring.

Gringas (2000) and Gringas and McNicholas (1999) offer suggestions for medication assessment as well as monitoring prescription drug use in children. In both articles they recommend observations in everyday settings, such as school playgrounds, to monitor effectiveness and side-effects. They also stress the importance of communication between the prescribing physician and the child’s teacher, as children are at school for many of their waking hours (Gringas, 2000). Other researchers suggest similar behavioral strategies for assessing whether the medication is having an effect (McCracken, 2005). Yet, in spite of the recommendations, experts in the field indicate that such guidelines may not be followed, and monitoring practices frequently are not based upon objective observations in natural environments, such as the child’s school (Morgan & Taylor, 2007). Research is needed to determine if, in fact, the guidelines regarding medication monitoring are actually being followed for children with ASD.

Further complicating the communication required to monitor medication effects, Raffin (2001) argues that since ASD is a complex diagnosis, a multidisciplinary approach should be taken so that the treatment decisions for each child can be based on perspectives from a variety of disciplines establishing common knowledge about the child. Such an approach involves the coordination of information across professionals, including the family, teachers, and other specialists who regularly interact with the child, and may result in improved practices relating to medication prescribing and monitoring (Myers & Johnson, 2007).

Although a plethora of literature exists on the types of medications that are being prescribed, the influence of coordinated feedback on prescription practices as well as the procedures for monitoring drug use, have not been carefully studied (Scahill & Martin, 2005). A lack of collaboration among professionals with regard to medications has been documented with populations other than ASD, including various developmental and learning disabilities (Vereb & DiPerna, 2004) as well as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) for which prescription medication use is widespread (Castle, Aubert, Verbrugge, Khalid, & Epstein, 2007; Weithorn & Ross, 1975). Similar to the recommendations made by experts in the field of autism, researchers in these other areas have stressed the importance of having the prescribing physician combine information from parents and teachers in the decision making process (Swanson, Lerner, March & Gresham, 1999). Specifically, these authors assert that teachers are in an excellent position to report on whether the medication is having a beneficial or adverse effect on behavior. In fact, close monitoring of medication effects may be even more important for children with ASD than children with ADHD because children on the autism spectrum are often prescribed medications with more serious and common adverse effects than stimulants to manage irritability and aggression (Matson & Dempsey, 2008; Robb, 2010).

Although there are studies reporting the coordination of medication monitoring for children with ADHD (Anderson & Walcott, 2009; Gureasko-Moore, DuPaul, & Power, 2005), their conclusions cannot be assumed to apply to the care of children with autism. For example, children with ASD tend to be in classrooms with smaller teacher to child ratios and more active parent participation than the classrooms of most children with ADHD. Also, because there tends to be more support by teams of professionals with expertise in special education and related disciplines (e.g., speech & language therapists) than for children with ADHD, one might expect the possibility of an increased level of collaboration across providers of students with ASD. Given the common use of medication or a combination of medications among this population, as well as the potential risks due to lack of monitoring, research in this area may be particularly informative. Without careful monitoring, medications may be ineffective and/or may even have harmful side effects, including weight gain, fatigue, tremors, drooling, tardive dyskinesia, greater pulse rate and systolic blood pressure for individuals with ASD (Arnold et al., 2003; McCracken, 2005; Shea et al., 2004). The benefits may outweigh the risks if improvements in behavior and learning are occurring; however, if such positive effects are not evidenced, or if deterioration of behavior occurs, the risk of side effects may not warrant continued use of medication (McCracken, 2005).

The current study is an initial step in gathering information relating to current practices in medication monitoring for children on the autism spectrum. Given the high use of medication in this population, as well as the lack of literature on the monitoring of side effects and behavioral changes due to medication, this study asked: 1) Are teachers knowledgeable regarding whether or not their students with ASD are being given medication? Further, since there may be behavioral side effects of specific medications and dosages that could positively or negatively influence the child’s response to learning tasks, we asked: 2) Are teachers knowledgeable about the specific type and dosage of medication their students with ASD are prescribed?; and 3) Is there coordination of information between the teachers and the families of children with ASD and the prescribing physician? In order to answer these questions, teachers of children with ASD who were on prescription medication were asked to fill out a questionnaire. Teachers of children with ASD who were not on prescription medication were also asked to fill out the questionnaire in order to have a comparison group.

Method

Participants

In order to select participant children, 115 parents of students with ASD in schools in Santa Barbara and Los Angeles Counties were surveyed. All of the students were also receiving in-home behavioral intervention services from Santa Barbara and Los Angeles agencies specializing in behavioral intervention for children with ASD. The students: 1) had a diagnosis of ASD by a community provider and confirmed by our Centers according to the DSM criteria (APA, 2000) after a comprehensive evaluation; 2) were in pre, elementary, or middle school under the category of autism and were fully included in regular education classrooms or enrolled in special day classrooms for students with disabilities; 3) spent the majority of the school day with one teacher; and 4) the child’s primary care provider (all were parents) agreed to provide information regarding medication. All of the participants had Individual Education Programs (IEPs), all had case managers, and in-home state-funded programs that included parent education. Parents were surveyed to determine if their child was taking prescription medication. Of the 115 surveys administered to parents, 100 were returned. Of the 100 returned, 19 parents reported that their child was taking prescription medication. These parents, and their child’s teacher (parent-teacher pairs) were asked to participate in a survey study. Fifteen of the 19 parents and teachers agreed to participate. Of the 4 who did not agree to participate, 3 were parents and 1 was a teacher. In order to create a comparison group for the 15 participants who were being given medication (and whose teachers and parents agreed to participate), the first 15 children who were not taking medication and who were relatively similar in mean grade, age, and gender were invited to participate and all of the children’s parents and teachers agreed. None of the 30 children who participated had the same teacher. Demographic data and medications each child was prescribed are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data for participant children.

| Children with ASD on Medication (N=15) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | Age | Grade | Ethnicity | Gender | Diagnosis | Medication |

| 1 | 7 | 1st | Caucasian | M | Autism | Abilify |

| 2 | 13 | 8th | Caucasian | M | Autism | Abilify/Risperdal |

| 3 | 8 | 2nd | Caucasian | M | Autism | Risperdal |

| 4 | 12 | 6th | Caucasian | F | Autism | Stimulant |

| 5 | 11 | 5th | Caucasian | F | Autism | Trileptal/Depakene |

| Cerebral Palsy | ||||||

| Seizure Disorder | ||||||

| 6 | 10 | 4th | Caucasian | M | Autism | Risperdal |

| 7 | 12 | 6th | Caucasian | M | Autism | Risperdal |

| 8 | 12 | 6th | Caucasian | M | Autism | Adderall |

| 9 | 10 | 4th | Caucasian | M | Autism | Risperdal/Lamictal/Strattera |

| 10 | 11 | 5th | Caucasian | M | Autism | Risperdal |

| 11 | 13 | 8th | Caucasian | M | Autism | Risperdal |

| 12 | 12 | 7th | Caucasian | M | Autism | Risperdal |

| 13 | 12 | 6th | Caucasian | M | Autism | Anti-Seizure |

| Seizure Disorder | ||||||

| 14 | 12 | 6th | Hispanic | F | Autism | Topomax/Naproxen |

| 15 | 10 | 4th | Caucasian | F | Autism | Trileptal |

| Children with ASD Not on Medication (N=15) | ||||||

| 1 | 7 | 1st | Caucasian | M | Autism | |

| 2 | 7 | 1st | Caucasian | M | Autism | |

| 3 | 7 | 1st | Caucasian | M | Autism | |

| 4 | 11 | 5th | Caucasian | F | Autism | |

| 5 | 10 | 4th | Hispanic | F | Autism | |

| 6 | 8 | 2nd | Hispanic | F | Autism | |

| 7 | 6 | K | Caucasian | M | Autism | |

| 8 | 10 | 4th | Caucasian | M | Autism | |

| 9 | 8 | 2nd | Hispanic | M | Autism | |

| 10 | 11 | 5th | Hispanic | M | Autism | |

| 11 | 12 | 6th | Caucasian | M | Autism | |

| 12 | 9 | 3rd | Caucasian | M | Autism | |

| 13 | 6 | K | Hispanic | M | Autism | |

| 14 | 6 | K | Hispanic | M | Autism | |

| 15 | 9 | 3rd | Caucasian/Hispanic | M | Autism | |

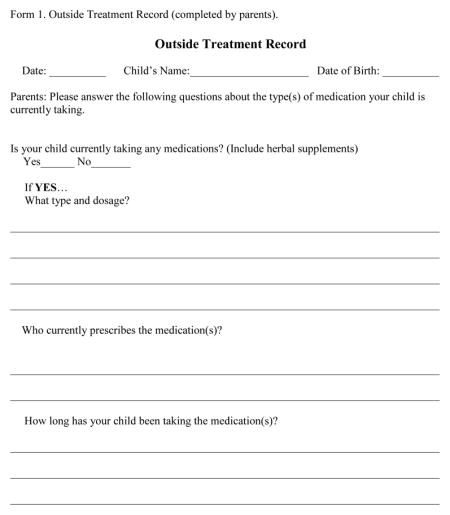

Measures

The measures used in this study included an Outside Treatment Record Form completed by the child’s family (see Appendix A), which asked the child’s family if their child was currently taking a prescription medication, what type and dosage, the length of time the child was taking medication and the prescribing physician. The Medication Questionnaire form was completed by the child’s teacher (see Appendix B). The questionnaire included items such as: Is the child taking any medications? If the teachers reported that the child was taking medication, they were asked what medication is the child is being given and the dosage. Finally, the teachers were asked questions relating to the coordination of medication information. In this section on the questionnaire, the teacher had the option to report if the information was coordinated through data collection, phone conversation, meetings, or in a way that was not listed. In addition, the questionnaire provided a space to report the frequency of the coordination of information.

Procedures

A copy of the Outside Treatment Record (Appendix A) was given to all families. Next, the parents were asked for permission to contact their child’s teacher regarding his or her knowledge of the medications. If the parents consented, then either the primary researcher of the study, or the program supervisor/clinician of the treatment team working with the family at home went to the child’s school to give the questionnaire to the teacher in person. The questionnaire was given to the teachers as close as possible in time after the parents provided consent to contact the teachers.

Results

Descriptive statistics were calculated to determine how many teachers in each group correctly reported whether or not the children were taking medication, the type and dosage of the medication, and whether they reported information to the prescribing physician regarding observed behavioral changes and/or side effects. Although the two groups were relatively similar on many demographic variables, ethnicity was different between groups, with many fewer Hispanic children in the medication group. The two groups also differed slightly with regard to age levels.

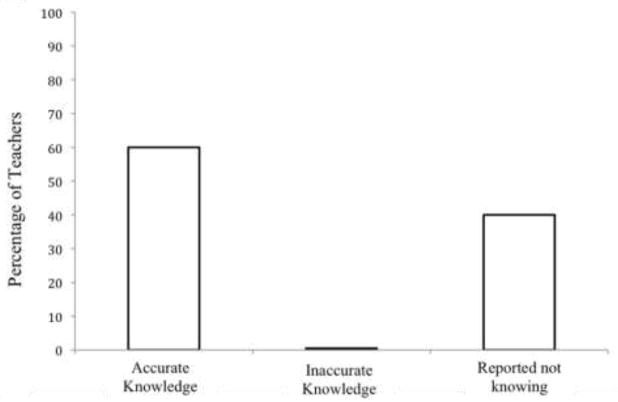

The first question asked in this study was “Are teachers knowledgeable regarding whether or not their students with ASD are taking medication?” The question asked on the questionnaire was “Is the child taking any medications?” The specified options for an answer were “yes,” “no,” and “I don’t know.” Figure 1 shows results regarding whether or not the teachers knew if their participating students with ASD were taking medication. For this group, 60% of teachers reported correctly that their student was taking prescription medication and 40% reported not knowing if the child was being given medication. A chi-square goodness of fit test was run on the data to see if the teachers’ responses differed from chance responding (Cohen, 1977). This test was selected because it can be applied to small sample sizes with nominal data, and does not require an assumption of normally distributed data (McDonald, 2009). The expected values for the test were assumed to be equal for all three possible answers, “yes,” “no,” and “I don’t know,” to the question about if they knew that the student was being given medication. An alpha level of 0.05 showed that the observed values were significantly different than the expected values, c2 (2, N = 15) = 8.4, p = .015. These results show that the teachers were more likely to answer either: (1) correctly that the student was on medication, or (2) that they did not know whether the student was being given prescription medication.

Figure 1.

Teacher report for children with ASD who are currently taking medication (N = 15).

Figure 2 shows the teacher report results for the students with ASD in the comparison group who were not taking medication. The results indicate that 53% of teachers reported correct knowledge of the medication status of the child. That is, their responses confirmed the parents’ report that the child was not being given any medication. Thirteen percent of teachers reported incorrectly that their students were being given medication when they were not. Thirty three percent reported that they did not know whether or not the child was being given medication. A chi-square test was also run on the data from this group. The expected values were that the teachers would respond equally across the three possible answers. For the data from this group, it was found that the teachers’ observed responses were not significantly different than the expected rate of responding, c2 (2, N = 15) = 3.6, p = .17. This means that the teachers did not mark any one answer more than the others at a greater than chance level, indicating that as a group they were not knowledgeable about whether or not the children with ASD were being given medication. The results from question 1 suggest that, as a whole, the teachers have very little knowledge regarding whether a student in their classroom with ASD is being given medication/s.

Figure 2.

Teacher report for children with ASD who are currently not taking medication (N = 15).

When comparing the two groups, a similar percentage reported correct knowledge about whether or not the child was being given prescription medication. While none of the teachers of children being given prescription medication reported incorrect information, two of the teachers of children not being given prescription medication reported that the children were being given medication. In both groups, many teachers reported that they did not know whether or not the child was being given prescription medication. The chi-square results show that while the teachers of children who were being given medication were more likely to report that the children were being given medication or that they did not know, for the non-medication group, teachers did not mark any one answer more than the others at a greater than chance level.

The second question asked in this study was “Are teachers knowledgeable about the specific type and dosage of medication their students with ASD are prescribed? Figure 3 shows results of this question. Of the 60% of teachers who correctly reported that the child was being given medication, 55% of those teachers reported correct information regarding what type of medication the child was being given. Eleven percent reported correct information regarding the dosage the child was being given. Thirty-three percent of the teachers reported not knowing either the type or dosage of medication. That is, only about half of the teachers reported correct information about what medication/s the child was prescribed, only 11% had information regarding the dosage, and a third reported having no information whatsoever regarding either medication type or dosage.

Figure 3.

Teacher report of the specific type and dosage of medication their students with ASD are prescribed.

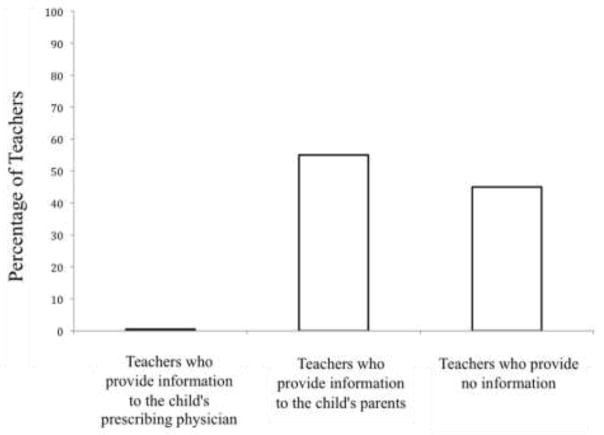

The final question asked was “Is there coordination of information between the teachers and the families of children with ASD and the prescribing physician?” Again, this question was asked to the 60% of teachers who correctly reported that the child was being given medication. Figure 4 shows that none of the teachers reported that they were providing any type of information regarding positive/negative behavior changes or potential side effects to the child’s prescribing physician. Fifty-five percent in this group reported that they did provide information to the child’s parents regarding the child’s overall behavior, but none reported collecting systematic data. This information was reported on the questionnaire under the “Other” category when asked how information is coordinated with the child’s prescribing physician. One teacher reported providing general information on positive/negative behavior changes, although the teacher noted “if necessary”, and four teachers reported providing information concerning side effects to the parents. Overall, the teachers had no contact with prescribing physicians and no systematic reporting system was employed..

Figure 4.

Teacher report of coordination of medication information.

Discussion

Similar to the results related to this question in the ADHD literature (Gureasko-Moore et al., 2005; Haile-Mariam, Bradley-Johnson, & Johnson, 2002), the findings of this study indicate that although some teachers had accurate information about whether the child is on medication, most teachers of children who were medicated did not know the medication type and dosage. Furthermore, none of the teachers reported that they were providing medication information to the children’s prescribing physicians. Given the call in the literature for monitoring information regarding medication across professionals, it is interesting that in practice it is uncommon. The outcome of this research is similar to the results of studies with ADHD students indicating that there is very little exchange of information regarding medications. Swanson and colleagues (1999) reported on the consensus of a National Institute of Health (NIH) panel which concluded there is an existing disconnect between physician related services and school-based services for children with ADHD. This study shows that there is an analogous gap between physician and school-based services for children with ASD. Despite the fact that the students in this study had more intensive interventions with highly educated special education staff than many children with ADHD who participate in regular education classes with few or no ancillary services, there was still very little communication in regard to medication. These results suggest a need to develop a collaborative model so that family members, education personnel, and medical professionals can enhance their effectiveness in evaluating the effects of medication on the behavior of students with ASD.

The use of psychopharmacology for children with ASD is increasing (Gerhard, Chavez, Olfson, & Crystal, 2009) and there remains a lack of knowledge about the adverse side effects and long-term safety concerns of taking prescribed medication (Gerhard et al., 2009; Koelch, Schnoor, & Fegert, 2008). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved unrestricted risperidone use for this population. Risperidone is becoming widely used to treat various behavioral symptoms of autism including aggression and self-injury. According to the findings of the current study, many physicians appear to prescribe without gathering information of the beneficial or harmful effects of the medication from teachers. Keeping track of the effects of a medication, including biological information before, during, and following treatment (e.g. height, weight, sexual maturation), as well as behavior change is important to assess whether prescribed medications are effective. In addition, the side effects for some medications commonly prescribed for individuals with autism can include weight gain, constipation, fatigue, insulin resistance, tardive dyskinesa, and seizures (Toost, Lahuis, Steenuis, et al., 2005). These side effects may be short- or long-term and should be monitored. Although it is easier for a prescribing physician to collect systematic measures of a child’s weight than a child’s behavior, behavioral data is critically important and gathering these data have been recommended by many experts in the field (Gerhard et al., 2009; Oswald & Sonenklar, 2007; Steinberg-Epstein, Book, & Wigal, 2011). Recruiting teachers as partners to report the monitoring of medication effects may be an important component for ensuring the highest-level care for the child (Fey, Kelleher, & Laraque, 2012). Models of systems for communication between parents, teachers and physicians should include steps pertaining to all of these aspects of medication monitoring.

When considering models for coordinating medication treatment, our findings raise another important consideration related to the path of communication. Several teachers reported providing information to the child’s parents. There are advantages and disadvantages associated with relying solely on the parent as the conduit of information between behaviors observed by the classroom teacher and the prescribing physician. Parents of school age children with autism are frequently under heavy stress that could potentially cloud reporting information (Dabrowska & Pisula, 2010; Hall & Graff, 2011; Hastings, et al., 2005). However, since many teachers feel comfortable talking to parents about the child’s medication parents may be an ideal conduit for providing data collected at school to their pediatricians. Further, if parents were also able to collect objective and systematic data from teachers, this information could be beneficial in assessing the effects of the medication. For example, the use of behavioral log-forms that can be sent to prescribing physicians’ offices on a monthly or other regular basis is another practical and systematic method that can be explored to make sure there is a regular and correct information exchange (Galinat, Barcalow, & Krivda, 2005). Alternatively, other specialized staff, such as school nurses may be helpful conduits for providing information from teachers to prescribing physicians. Identifying practical and efficient pathways for sharing school data with prescribing physicians is an important part of the careful monitoring of medication effects, particularly because low agreement has been found between teachers and parents relating to ADHD symptoms (Wolraich, Lambert, Bickman, Doffing, & Worley, 2002).

Although our findings pertain to the role of teachers in the monitoring of behavior related to medication use, effective communication requires active collaboration on both ends of the communication. Pediatricians of children being administered medication for ADHD have reported that they would like to receive more information from schools (Haile-Mariam, et al., 2002); however, a study of the practices of psychiatrists suggested that even when school data was provided to psychiatrists to inform prescribing practices, the psychiatrists tended to place little value on these data and did not regularly attempt to collect data from teachers in their practice (Pliszka et al., 2003). Systems used to achieve collaborative care coordination may have to include procedures for educating some physicians and some teachers about the importance of sharing information and how the infroamtion from others can enhance their prescribing practices and their teaching practices.

There are several areas that would provide interesting avenues for future research given the results of this initial preliminary study. First, the sample size of this study was small. A larger sample size with more detailed information about the medications and characteristics of the teachers, students, and parents would allow investigators to understand the perceived benefits of sharing behavioral information from schools with physicians. The perspectives of parents, teachers and physicians on this issue could be helpful for improving coordination of care. Related, while the groups in this study were relatively similar on many demographic variables, ethnicity was different between groups, with more Latino children in the group who were not being given prescription medication. Given the design of this study, it is unlikely that child and family ethnicity affected the results; however, the role of family’s and professionals’ race, ethnicity and culture on this type of care coordination has not been studied and may offer useful insights into the variability in practices. Also, with an increased sample size, additional chi-square analyses could be done. In this study we examined teachers’ practices related to medication use and coordination of care. Clearly, coordinated care requires collaboration among many individuals and evaluating the practices and beliefs pertaining to communication across settings would improve our understanding of this area. For example, parents may have concerns about confidentiality that may prevent physicians and teachers from communicating about the education and medical practices being provided. Further, demographic data relating to variables such as student age, experience teaching, time spent with students, setting (general vs. special education), grade (pre- vs. elementary vs. middle/high school), and so on may also reveal some important variables that influence this system. In addition, out of the 100 families surveyed, only 19% reported that their children were on prescription medication. This is lower than current statistics regarding the percentage of children with ASD who are on prescription medication (Rosenberg et al., 2010). One possible reason for this is because these families were receiving behavioral treatment services and therefore a large percentage of them may not have found the need for adjunctive medication treatment. Finally, it would be helpful to have empirical studies documenting the benefits for children with ASD who receive coordinated care with consistent and informed communication between parents, teachers and physicians compared to those without such care. Studies show that teachers who collect regular behavioral data have better performing students (Farlow, & Snell, 1989; Fuchs & Fuchs, 1986; Koegel & Koegel, 2012). It would be helpful to have similar data regarding the benefit of monitoring information related to the prescribing practices of physicians.

The current study identified a problem in current practice. These findings represent an important start to the research needed to design coordinated systems of care and communication models for children with ASD. Future research is warranted to assess whether systematic monitoring and coordination of information across professionals for the treatment of a child with an ASD results in improved performance and outcomes. This coordination may be helpful for ensuring that children with ASD receive optimal services, and the present study suggests the importance of system change regarding reporting standards. In short, there may be benefits to working as a collaborative team in regard to prescription medication use, with relevant individuals from the child’s home and school in close coordination with the prescribing medical physician.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Contributor Information

Lynn K. Koegel, Counseling, Clinical, & School Psychology, University of California, Santa Barbara

Anna M. Krasno, Counseling, Clinical, & School Psychology, University of California, Santa Barbara

Howard Taras, Pediatrics, Rady Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Diego

Robert L. Koegel, Counseling, Clinical, & School Psychology, University of California, Santa Barbara

William Frea, William Frea, Autism Spectrum Therapies, Los Angeles, California

References

- Aman MG, Lam KSL, Van Bourgondien ME. Medication patterns in patients with autism: Temporal, regional, and demographic influences. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2005;15:116–126. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. Text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L, Walcott CM. Issues in monitoring medication effects in the classroom. Psychology in the Schools. 2009;46(9):820–826. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LE, Vitiello B, McDougle C, Scahill L, Shah B, Gonzalez NM, Tierney E. Parent-defined target symptoms respond to risperidone in RUPP autism study: Customer approach to clinical trials. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(12):1443–1450. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200312000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle L, Aubert RE, Verbrugge RR, Khalid M, Epstein RS. Trends in medication treatment for ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2007;10:335–342. doi: 10.1177/1087054707299597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghill D. Current issues in child and adolescent psychopharmacology. Part 2: Anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders, autism, Tourette’s and schizophrenia. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2003;9:289–299. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Orlando, FL: Academic Press, Inc; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska A, Pisula E. Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities Research. 2010;54(3):266–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebensen AJ, Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Aman MG. A longitudinal investigation of psychotropic and non-psychotropic medication use among adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:1339–1349. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0750-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farlow LJ, Snell ME. Teacher use of student instructional data to make decisions: Practices in programs for students with moderate to profound disabilities. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 1989;14(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Foy JM, Kelleher KJ, Laraque D. Enhancing pediatric mental health care: Strategies for preparing a primary care practice. Pediatrics. 2010;125:S87–S108. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0788E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D. Effects of Systematic Formative Evaluation: A Meta-Analysis. Exceptional Children. 1986;53(3):199–208. doi: 10.1177/001440298605300301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinat K, Barcalow K, Krivda B. Caring for children with autism in the school setting. Journal of School Nursing. 2005;21(4):208–217. doi: 10.1177/10598405050210040501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard T, Chavez B, Olfson M, Crystal S. National patterns in the outpatient pharmacological management of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;29:307–310. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181a20c8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green V, Pituch K, Itchon J, Choi A, O’Reilly M, Sigafoos J. Internet survey of treatments used by parents of children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2006;27(1):70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gringras P. Practical paediatric psychopharmacological prescribing in autism. Autism. 2000;4:229–247. [Google Scholar]

- Gringas P, McNicholas F. Developing rational protocols for paediatric psychopharmacological prescribing. Child: Care, Health, and Development. 1999;25:223–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.1999.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureasko-Moore DP, DuPaul GJ, Power TJ. Stimulant treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Medication monitoring practices of school psychologists. School Psychology Review. 2005;34:232–245. [Google Scholar]

- Haile-Mariam A, Bradley-Johnson S, Johnson CM. Pediatricians’ preferences for ADHD information from schools. School Psychology Review. 2002;31:94–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hall HR, Graff JC. The relationships among adaptive behaviors of children with autism, family support, parenting stress, and coping. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2011;34(1):4–25. doi: 10.3109/01460862.2011.555270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP, Kovshoff H, Brown T, Ward NJ, Espinosa FD, Remington B. Coping strategies in mothers and fathers of preschool and school-age children with autism. Autism. 2005;9(4):377–291. doi: 10.1177/1362361305056078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel RL, Koegel LK. The PRT Pocket Guide. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Company; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Koelch M, Schnoor K, Fegert JM. Ethical issues in psychopharmacology of children and adolescents. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2008;21:598–605. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328314b776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leskovec TJ, Rowles BM, Findling RL. Pharmacological treatment options for autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2008;16:97–112. doi: 10.1080/10673220802075852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptak GS, Stuart T, Auinger P. Health care utilization and expenditures for children with autism: Data from U.S. national samples. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36:871–879. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Morales KH, Marcus SC, Stahmer AB, Doshi J, Polsky DE. Psychotropic medication use among Medicaid-enrolled children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e441–e448. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL, Dempsey T. Autism spectrum disorders: Pharmacotherapy for challenging behaviors. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2008;20:175–191. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken JT. Safety issues with drug therapies for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:32–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JH. Handbook of Biological Statistics. 2. Baltimore, MD: Sparky House Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S, Taylor E. Antipsychotic drugs in children with autism. British Medical Journal. 2007;334:1069–1070. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39216.583333.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers SM, Johnson CP. Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1162–1182. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald PD, Sonenklar NA. Medication use among children with autism-spectrum disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2007;17:348–355. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.17303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka SR, Lopez M, Crismon ML, Toprac MG, Hughes CW, Emslie G, Boemer C. A feasibility study of the Children’s Medication Algorithm Project (CMAP) algorithm for the treatment of ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:279–287. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posey DJ, Sigler KA, Erickson CA, McDougle CJ. Antipsychotics in the treatment of autism. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118(1):6–14. doi: 10.1172/JCI32483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffin C. A multidisciplinary approach to working with autistic children. Educational and Child Psychology. 2001;18(2):15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Robb AS. Managing irritability and aggression in autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Developmental Disabilities Research Review. 2010;16(3):258–264. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg RE, Mandell DS, Farmer JE, Law JK, Marvin AR, Law PA. Psychotropic medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders enrolled in a national registry, 2007–2008. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40:342–351. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0878-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Martin A. Psychopharmacology. In: Volkmar FR, Paul R, Klin A, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2005. pp. 1102–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Shea S, Turgay A, Carroll A, Schulz M, Orlik H, Smith I, Dunbar F. Risperidone in the treatment of disruptive behavioral symptoms in children with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e634–e641. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0264-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg-Epstein R, Book T, Wigal SB. Controversies surrounding pediatric psychopharmacology. Advances in Pediatrics. 2011;58:153–179. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J, Lerner M, March JS, Gresham F. Assessment and intervention for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the schools. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 1999;46:993–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troost PW, Lahuis B, Steenhuis M, Ketelaars CE, Buitelaar JK, van Engeland H, Hoekstra PJ. Long-term effects of risperidone in children with autism spectrum disorders: a placebo discontinuation study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(11):1137–1147. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000177055.11229.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vereb RL, DiPerna JC. Teachers’ knowledge of ADHD, treatments for ADHD, and treatment acceptability: An initial investigation. School Psychology Review. 2004;33:421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar FR, Lord C, Bailey A, Schultz RT, Klin A. Autism and pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:135–170. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar FR, Wiesner LA, Westphal A. Healthcare issues for children on the autism spectrum. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2006;19:361–366. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000228754.64743.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weithorn CJ, Ross R. Who monitors medication? Journal of Learning Disabilities. 1975;8:458–461. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson ED, Martin A. Psychotropic medications in autism: Practical considerations for parents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;42(6):1249–1255. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witwer A, Lecavalier L. Treatment incidence and patterns in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2005;15:671–681. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolraich ML, Lambert EW, Bickman L, Simmons T, Doffing MA, Worley KA. Assessing the impact of parent and teacher agreement on diagnosing attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Development and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2002;25:41–47. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200402000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]