Abstract

This case describes the unexpected survival of an adult man who presented to the emergency department with hypovolaemic shock secondary to a splenic haemorrhage. Before surgery he had a pH 6.527, base excess (BE) −34.2 mmol/l and lactate 15.6 mmol/l. He underwent a splenectomy after which his condition stabilised. He was managed in the intensive care unit postoperatively where he required organ support including renal replacement therapy but was subsequently discharged home with no neurological or renal deficit. Although there are case reports of patients surviving such profound metabolic acidosis these have mainly been cases of near drowning or toxic alcohol ingestion. To the best of our knowledge this is the first reported case of survival after a pH of 6.5 secondary to hypovolaemic shock.

Case presentation

A 65 year old man presented to the emergency department after a collapse at home. There had been no preceding symptoms or illness. He had a past medical history of atrial fibrillation, gout and acne rosacea and his drugs comprised digoxin, aspirin, omeprazole and oxytetracycline. He did not receive warfarin.

On initial assessment he was shocked with cool peripheries and hypotension, in atrial fibrillation with a heart rate of 90 and a blood pressure of 80/40 mm Hg. He was apyrexial with no evidence of cardiac failure and no complaints of chest pain. He had mild, diffuse tenderness at his epigastrium but no peritonism. There was no evidence of gastrointestinal blood loss.

Routine blood investigations showed a raised white cell count at 16.0×109/l and normal haemoglobin of 12.6 g/dl. Venous blood gas analysis showed a lactate level of 5.4 mmol/l but was otherwise unremarkable.

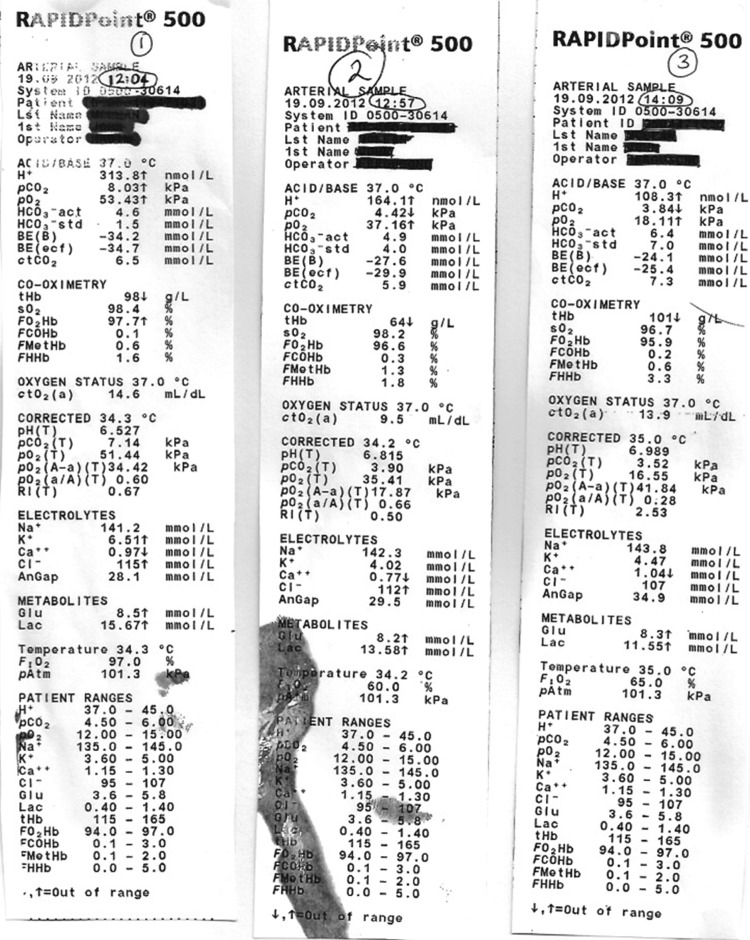

He received 3 litres of 0.9% NaCl over the next 2 h with no improvement in his haemodynamic profile. He then rapidly deteriorated with severe abdominal pain and increasing agitation. A plan to obtain an abdominal CT scan was abandoned owing to haemodynamic instability and agitation. An abdominal ultrasound scan in the resuscitation room showed minimal free fluid and no evidence of an abdominal aortic aneurysm or solid organ abnormality. Treatment was started with an adrenaline infusion and he underwent rapid sequence induction and intubation in the emergency department. After resuscitation from a brief pulseless electrical activity (PEA) cardiac arrest he was transferred to theatre for an emergency laparotomy. On arrival in theatre he had a profound metabolic acidosis with a pH of 6.527 (hydrogen ion 313 nmol/l), base excess (BE) −34.2 mmol/l and lactate 15.6 mmol/l, see figure 1. At this point he had a blood pressure of 58/32 mm Hg, heart rate 150 bpm, arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) 90% on fractional inspired oxygen (FiO2) 0.98 and core temperature of 34°C. He continued with an adrenaline infusion.

Figure 1.

Serial arterial blood gases in theatre.

Laparotomy showed marked bleeding from the distal splenic artery. This was ligated and a splenectomy was performed, although the spleen itself appeared to be intact. After this the brisk bleeding settled and the abdomen was closed with drains remaining in situ. The patient required 10 units of packed red cells, 8 units of fresh frozen plasma and two pools of platelets in the perioperative period. By the end of surgery his arterial pH was 6.989, BE −24.1 mmol/l and lactate 11.5 mmol/l

Standard quality control and calibration tests were carried out on the blood gas analyser used in this case and no problems were detected. In particular, the blood gas analyser was used to carry out calibrations at 12:00—4 min before the first theatre sample, and again at 12:33, both of which were satisfactory. It also underwent a quality control run at 08:01 that day and again later in the day at 20:01, which were also satisfactory.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperatively the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for ventilation, inotropic support and renal replacement therapy for an acute kidney injury. His metabolic acidosis continued to improve over the next few hours and he was extubated 5 days later. He was discharged to the renal high dependency unit for further haemodialysis. He has now made a full recovery and was recently discharged from hospital with no residual neurological or renal deficit.

Pathological analysis of the spleen did not show any focal lesions or neoplasia. It did show capsular stripping with associated thrombus formation and mild reactive changes in the white pulp, predominately in the form of marginal zone hyperplasia.

Discussion

Tight regulation of pH in extracellular fluid is essential for normal cellular function. A normal pH is generally described as being between 7.36 and 7.44 and physiology textbooks would describe a pH outside the range 7.00–7.70 as being incompatible with life.1

The patient in this case developed a profound metabolic acidosis due to a major imbalance between tissue oxygen supply and demand, which was compounded by his cardiac arrest.

At the time of the initial blood gas analysis in theatre the patient was noted to be hyperchloraemic with a chloride of 115 mmol/l. It is known that the rapid administration of isotonic saline can result in a hyperchloraemic metabolic acidosis2 through an excessive rise in plasma chloride leading to a reduction in the strong anion gap and excessive renal elimination of bicarbonate.3

We are aware of several cases of profound metabolic acidosis following ethylene glycol and ethylene glycol with methanol intoxication. In these cases the lowest capillary pH recorded was 6.712 in a 45-year-old man who had ingested ethylene glycol alone. The second case was a 54-year-old man who had ingested a combination of ethylene glycol and methanol, the lowest pH recorded in this case was 6.745. Both patients developed multiorgan complications but survived with supportive care and multiple haemodialysis.4 It is not known whether these patients made a complete recovery. However, in a similar case a 36-year-old woman survived a pH of 6.6 after ethylene glycol ingestion and went on to make a full recovery after a prolonged period of intensive care and rehabilitation.5

Survival from extreme metabolic acidosis has also been described in a case of near drowning. A 24-year-old man survived a profound metabolic acidosis after near drowning in sea water followed by a cardiac arrest. He had a post-resuscitation pH of 6.33 and made a full neurological recovery, which may be partly due to his hypothermia at the time of arrest.6

We are aware of one other adult patient who also had a cardiac arrest associated with profound metabolic acidosis secondary to metformin-induced lactic acidosis. He had a post-resuscitation pH of 6.481 and made a full recovery.7

This case illustrates that with prompt intervention and treatment of the precipitating cause, survival is possible even at extremes of acid–base disturbance. We are unaware of any other cases of patients surviving a pH of 6.5 due to hypovolaemic shock. As the patient said, ‘Could I really hold the world record?’.

Learning points.

Spontaneous rupture of the splenic artery is an unusual cause of hypovolaemic shock.

Survival from extreme acidosis is possible with prompt correction of the precipitating cause.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ganong W. Review of medical physiology. 19th edn Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prough DS, Bidani A. Hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis is a predictable consequence of intraoperative infusion of 0.9% saline. Anesthesiology 1999;90:1247–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenhut M. Causes and effects of hyperchloremic acidosis. Crit Care 2006;10:413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kostek H, Kujawa A, Szponar J, et al. Is it possible to survive metabolic acidosis with a pH measure of below 6.8? A study of two cases of inedible alcohol intoxication. Przeglad Lekarski 2011;68:518–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kujawa A, Kostek H, Szponar J, et al. Extremely severe metabolic acidosis and multi-organ complications in ethylene glycol intoxication: a case study. Przeglad Lekarski 2011;68:530–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Opdahl H. Survival put to the acid test: Extreme arterial blood acidosis (pH 6.33) after near drowning. Critical Care Medicine 1997;25:1431–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spencer C, Randic L, Butler J. Survival following profound lactic acidosis and cardiac arrest: does metformin really induce lactic acidosis. JICS 2009;10:116–17 [Google Scholar]