Abstract

A 52-year-old gentleman presented with 1-week history of severe right-sided headache associated with reduced vision in his right, amblyopic eye. Examination revealed raised intraocular pressure at 64 mm Hg. The anterior chamber (AC) was shallow and there was a dense cataract with no red reflex or fundal view. The contralateral eye had a deep anterior chamber with normal pressure and a clear lens. He was treated initially for acute angle closure glaucoma. The anterior chamber remained shallow and the intraocular pressure uncontrolled, despite maximum medical therapy. Owing to the absent fundal view and unilateral AC shallowing, further imaging was performed and a choroidal mass was found to be responsible for anterior displacement of the lens and shallowing of the angle. He went on to have an enucleation of the right eye, and histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of choroidal melanoma.

Background

Choroidal melanoma is known to be the most common primary malignant intraocular tumour in adults. Patients can present with flashing light, floaters, decreased visual acuity or visual field loss, but most of the time, the tumours are detected by chance on routine fundal examination. Early diagnosis of this condition is important for long-term visual and systemic outcome. We report a rare case where the patient presented with unilateral acute angle closure glaucoma but was subsequently found to have a massive choroidal melanoma causing cataract formation and displacement of the lens anteriorly. We emphasise the importance of ruling out secondary causes of acute angle closure glaucoma especially in unilateral cases. We also discuss the management dilemma in this case.

Case presentation

A 52-year-old man presented to the emergency service with 1-week history of painful right eye associated with reduced visual acuity. He revealed having attended another hospital 3 days before where he was diagnosed and treated for high pressure in the eye but failed to attend for follow-up the next day.

He was known to be hypermetropic bilaterally, with an amblyopic right eye in which he had strabismus surgery at the age of 18. He denied any previous ocular trauma. He also had a medical history of alcohol misuse and deliberate self-harm.

On examination, his best-corrected visual acuity was counting fingers in the right and 6/12 in the left. Slit lamp examination of the right eye revealed corneal oedema, a shallow anterior chamber and an intraocular pressure (IOP) of 64 mm Hg. He was also noted to have a dense cataract which completely obscured fundal view. Gonioscopy was not performed as he was intolerant to it. The left eye had a deep anterior chamber, normal IOP and a clear lens.

A diagnosis of acute angle closure glaucoma secondary to the dense cataract (phacomorphic glaucoma) was made. Despite maximum medical therapy and peripheral laser iridotomy, his IOP remained above 35 mm Hg.

Investigations

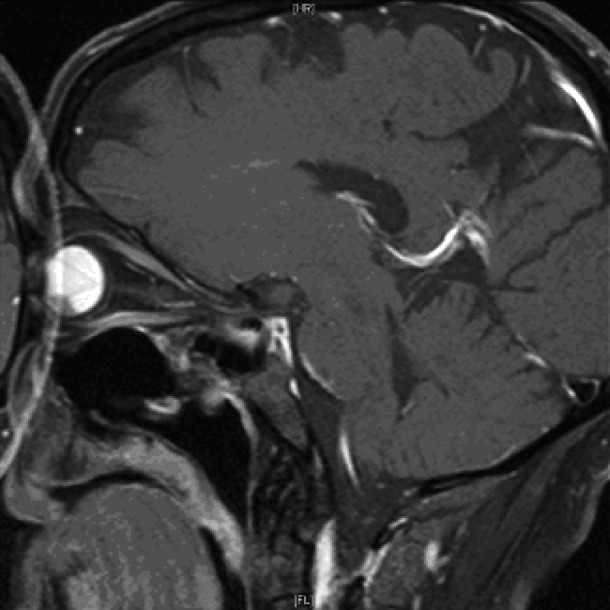

Lens extraction was subsequently contemplated. In the absence of fundal view, B-scan ultrasonography was performed prior to surgery to rule out any posterior segment pathology (figure 1). Unfortunately, the quality of the images was poor but revealed a suspicious dome-shaped elevation of unknown origin. He went on to have an MRI scan of the head and orbit (figure 2) which confirmed an intraocular mass measuring at 13×11×5 mm arising from the anterior-inferior aspect of the choroid, pushing anteriorly against the lens and causing a shallowing effect of the anterior chamber. The mass demonstrated low signal on T1-weighted image and high signal on T2-weighted image. There was also complete retinal detachment with vitreous haemorrhage and subretinal haemorrhage.

Figure 1.

B-scan examination revealed a dome-shaped elevation of unknown origin inferiorly.

Figure 2.

T1-weighted image of MRI orbit (sagittal view) showed an anterobasal low signal intraocular mass arising from the choroids. There was also total retinal detachment with vitreous and subretinal haemorrhage.

Differential diagnosis

At the top of the differential diagnosis was choroidal melanoma. However, none of the features from the imaging studies were pathognomonic of a choroidal melanoma. Although the diagnosis of choroidal melanoma was not definitive, it was noted from the MRI scan that there was a large choroidal mass displacing the lens anteriorly and resulting in total retinal detachment.

Treatment

This case warranted referral to the ocular-oncologists for an expert opinion. Treatment options were (1) extraction of lens followed by vitrectomy and biopsy of the mass to confirm diagnosis and (2) enucleation.

The case was discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting. In view of the eye being an amblyopic eye with poor visual prognosis and given a history of non-compliance with medical follow-up, it was agreed that enucleation was in the best interest of the patient. The pros and cons were carefully discussed with the patient.

Outcome and follow-up

Enucleation of the right eye with silicon implant was performed 11 days after the initial presentation. There was no macroscopic extrascleral extension of potential tumour. Histological examination confirmed the presence of choroidal melanoma predominated by spindle cells. There was full breach of Bruch's membrane with infiltration of the vortex vein but no optic nerve involvement. The patient denied other systemic symptoms and routine screening including chest x-ray, liver function tests and abdominal ultrasound were negative for metastasis of the tumour. No further radiotherapy or surgery was required and he will be followed up with annual CT brain, chest x-ray and biannual liver function tests and abdominal ultrasound.

Discussion

Choroidal melanomas are a subtype of uveal melanoma. Despite being the most common type of primary intraocular tumour in adult, they are still rare with only 6–8 cases per 1 million.1 2 It is more common in Caucasian females with a peak age of presentation between 50 years and 60 years.

The majority of choroidal melanomas are found incidentally on slit-lamp examination and fundoscopy.3 There have been several case reports in the literature where choroidal melanoma initially presented as acute angle closure glaucoma, but this is highly uncommon and a high index of suspicion is required.4–7 Escalona Benz et al5 reported two cases where the patients presented with refractory unilateral raised intraocular pressure, which when investigated with B-scan showed intraocular lesions consistent with malignancy. In both cases, the patients went on to have enucleation, with a positive histological diagnosis of choroidal melanoma. Schwartz et al7 reported a case of acute angle closure glaucoma in an elderly lady with bilateral narrow angles and was found to have choroidal melanoma in the eye with an acute attack following fundal examination with dilated pupil.

The diagnosis of choroidal melanoma is made through slit-lamp and fundal examination, ultrasonography and MRI. The diagnosis in this case had been challenging as there was no fundal view. The B-scan examination was inconclusive owing to poor image quality. MRI scan showed a choroidal mass with high intensity on T2-weighted images and low intensity in T1-weighted images. Although the opposite is more characteristic, it is not pathognomonic.8

Although there was no definitive evidence to confirm the diagnosis, the MRI scan did show the presence of an aggressive intraocular mass arising from the choroid. In the absence of other features to suggest a primary malignancy elsewhere, the diagnosis of choroidal melanoma was most likely. There is much controversy over management of intraocular melanoma. The collaborative ocular melanoma study (COMS) evaluated over 9000 patients in North America with choroidal melanoma.9 Tumour size played a great part in the choice of treatment. The treatment options include enucleation/exenteration, brachytherapy, radiotherapy and transpupillary thermotherapy. Enucleation is usually recommended in large tumours with extension around the optic nerve and when the visual prognosis is poor.10 Brachytherapy can be offered to a patient with a medium-sized tumour with good visual prognosis and the 12-year survival rates were similar to the enucleation group.11 According to the COMS classification, our patient had a medium-sized tumour as measured on the MRI scan. In view of the eye being an amblyopic eye with poor visual prognosis and, more importantly, given a history of non-compliance with medical follow-up, it was agreed by a multidisciplinary team that enucleation was in his best interest.

Long-term follow-up of patients with choroidal melanoma is important for monitoring of orbital recurrence and systemic metastasis. The COMS found that <1% patients had metastatic melanoma at the time of screening, but over 30% developed metastatic disease during follow-up.9 It is therefore recommended that after diagnosis, patients should have, at the minimum, biannual liver function tests, and annual chest x-rayss, along with MRI orbit or ultrasonography of the treated eye.12

Our patient was also noted to have microscopic extrascleral extension of the tumour. Extraocular spread has been reported to carry a poorer prognosis for survival, with an overall death rate of between 66% and 73%, compared with 39% without extrascleral extension.13–15 There is agreement that massive extraocular spread should be treated by orbital exenteration13 15 but the management of microscopic extraocular extension remains controversial. Postenucleation external beam radiotherapy is used in certain centres, but there is little published data, to date, to suggest its efficacy. Taking into consideration the significant morbidities associated with radiation therapy to the anophthalmic orbit, our patient did not have further treatment but will be followed up biannually.

In conclusion, this is a rare case of choroidal melanoma presenting as acute angle closure glaucoma where the initial diagnosis was challenging owing to various reasons discussed. We emphasised the importance of further imaging to rule out secondary causes of acute angle closure glaucoma in the absence of fundal view to allow timely detection of any mass lesion and to guide appropriate management.

Learning points.

Eye examination is essential in a patient presenting to the accident and emergency department with headache and nausea/vomiting complaining of red eye and reduced vision. All doctors should be aware of the signs and symptoms of acute angle closure glaucoma and urgent referral to an ophthalmologist is required.

Secondary causes of acute angle closure glaucoma should be considered especially in unilateral cases. Detailed fundal examination with dilated pupil after the initial attack and peripheral iridotomy should be routine in patients presented with angle closure glaucoma to rule out any mass effect especially in unilateral cases.

B-scan examination is important in the absence of fundal view prior to planning of surgery.

Management of intraocular malignancy should take into account patient's wishes, social history and likelihood of compliance with treatment.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Kanski JJ. Clinical ophthalmology: a systematic approach. 4th edn. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Factors predictive of growth and treatment of small choroidal melanoma: COMS Report No. 5. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115:1537–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zakka KA, Foos RY, Omphroy CA, et al. Malignant melanoma. Analysis of an autopsy population. Ophthalmology 1980;87:549–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kearns C, Boyer S, Gay D. Two differing presentations, treatments, and outcomes of malignant choroidal melanoma. Optometry 2008;79:365–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escalona-Benz E, Benz MS, Briggs JW, et al. Uveal melanoma presenting as acute angle-closure glaucoma: report of two cases. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;136:756–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Gottrau P, Holbach LM, Naumann GO. Acute glaucoma: first manifestation of malignant melanoma of the choroid. J Fr Ophthalmol 1993;16:275–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz GP, Schwartz LW. Acute angle closure glaucoma secondary to a choroidal melanoma. CLAO J 2002;28:77–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambers RB, Davidorf FH, McAdoo JF, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of uveal melanomas. Arch Ophthalmol 1987;105:917–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Margo CE. The collaborative ocular melanoma study: an overview. Cancer Control 2004;11:304–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell DJ, Wilson MW. Choroidal melanoma: natural history and management options. Cancer Control 2004;11:296–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melia M, Moy CS, Reynolds SM, et al. Quality of life after iodine 125 brachytherapy vs enucleation for choroidal melanoma: 5-year results from the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study: COMS QOLS Report No. 3. Arch Ophthalmol 2006;124:226–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, et al. Screening for metastasis from choroidal melanoma: the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Report 23. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:2438–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Starr HJ, Zimmerman LE. Extrascleral extension and orbital recurrence of malignant melanoma of the choroid and ciliary body. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1962;2:369–85 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byers WGM. Treatment of sarcoma of the uveal tract. Arch Ophthalmol 1935;14:967–74 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shammas HF, Blodi FC. Orbital extension of choroidal and ciliary body melanomas. Arch Ophthalmol 1977;95:2002–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]