Abstract

Limbic encephalitis (LE) is an inflammatory disorder of the limbic system; the clinical features are diverse, characterised by the development of neuropsychiatric symptoms, its aetiologies are various; syphilis is a rare entity. We report the case of a 50-year-old-man with syphilitic LE revealed by an inaugural status epilepticus. Diagnosis was made considering clinical, biological and radiological arguments. The patient received specific treatment for neurosyphilis. Evolution was marked by improved neuropsychological symptoms, the negativity of venereal disease research laboratory test in blood and cerebrospinal fluid and regression of the mesiotemporal signal abnormalities on MRI.

Background

Limbic encephalitis (LE) is an inflammatory disorder of the limbic system; it is manifested by memory disorder, psychosis, seizures; see an inaugural status epilepticus, and this is the case of our patient. Cerebral MRI may be normal at an early stage, but the pathognomonic lesions are seated at the limbic region and appear hyperintense on T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), without contrast enhancement. These aetiologies are diverse: paraneoplastic, inflammatory, autoimmune and infectious diseases especially herpetic; however, syphilis is a very rare clinical entity.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old-man, with a history of unprotected sex, was admitted to the emergency department for a status epilepticus tonic-clonic seizure.

Examination on admission: unconscious patient Glasgow coma score (GCS): 13, T: 37°C; blood pressure 120/80 mm Hg, glycaemia 1.02 g/l; neck supple, no sensorimotor deficit; deep tendon reflexes were present; normal tone; no facial paralysis in Pierre Marie and Foix manoeuvre.

Investigations

Cranial CT revealed a right temporal hyperdense lesion without contrast enhancement. Lumbar puncture showed 32 white blood cells with 95% lymphocytic, <3 red cells, with a hypoglycorrhachia to 0.68 g/l for a concomitant glycaemia with 1.22 g/l, hyperproteinorrachie to 0.83 g/l.

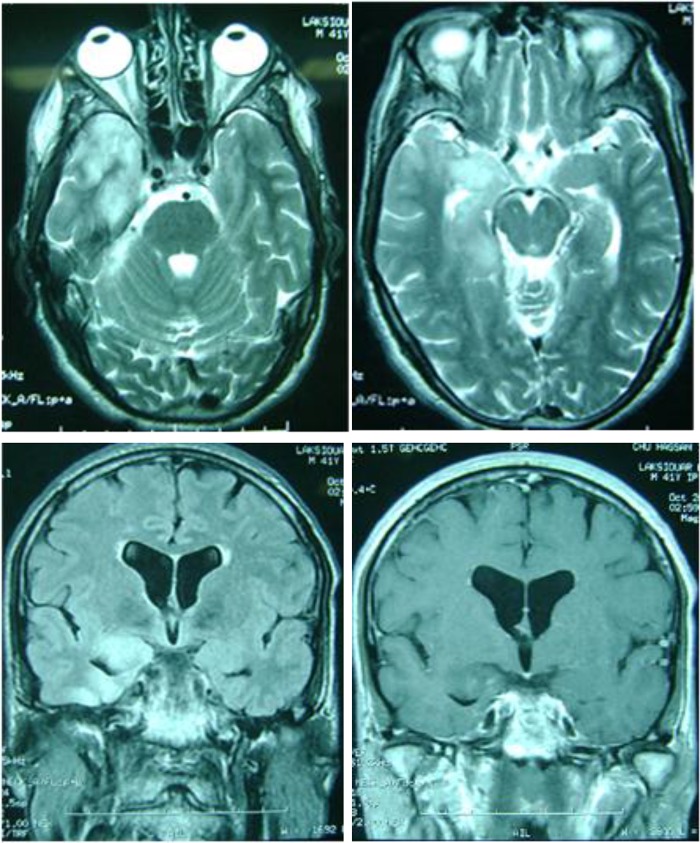

A brain MRI showed hippocampal lesions on hypersignal T2 and FLAIR bilateral, more marked on the right, without contrast enhancement (figure 1). The search of DNA of herpes simplex virus in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by PCR was negative; syphilis serology was positive in blood and CSF with venereal disease research laboratory test >1/64 and treponema pallidum hemagglutinations assay (TPHA) >2560. Serology for hepatitis B and C and HIV was negative. Thoraco-abdominopelvic CT scan was normal.

Figure 1.

MRI axial T2 (A and B) and coronal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery image (C), showing a hippocampal lesion on hypersignal. Coronal T1 sequence with gadolinium injection (D) shows a small enhancement.

EEG showed epileptiform activity in both the frontotemporal regions.

A neuropsychological test was performed with a mini-mental state at 21/30 normal, because he was illiterate. In testing of figure of Ray: the patient copied the image, but the reproduction of memory was not good; he realised what is general but not the details, reflecting a lesion on the right. He performed the Stroop test, and the Trail making test.

Differential diagnosis

LE is usually considered to be infectious especially herpetic, but recently, other aetiology was described: paraneoplastic, autoimmune disorders (lupus, Sjögren's, Hashimoto thyroiditis and central nervous system vasculitis), toxic and metabolic encephalopathy.1

Treatment

The patient was placed under a phenobarbital dose of discharge and dose of maintenance, after that it relied on valproate of sodium and benzodiazepine. In view of lymphocyte meningitis, the patient was put initially under acyclovir 10 mg/kg/8 h.

However, after the diagnosis of syphilis, LE was made considering clinical, biological and radiological arguments. The treatment by acyclovir was stopped, and changed to doxycycline 400 mg/day for 14 days in a month, for 9 months.

Outcome and follow-up

The evolution was marked by improved neuropsychological symptoms, the negativity of VDRL in blood and CSF and regression of the hippocampal signal abnormalities on MRI.

Discussion

The term LE was first used by Brierley and Corsellis in the 1960s. It was defined as an inflammatory disorder of the great limbic lobe. The neuropathological findings include mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrates, loss of neurons and proliferation of astrocytes and microglia in the hippocampus and amygdala.2

However, sometimes LE was limited to lesions of the hippocampus, sometimes remote to limbic lobe or extra-limbic. According to the authors, the ‘limbic lobe’ included the uncus, the amygdala, the hippocampus, the limen insulae, the hippocampal gyrus and the cingulate gyrus. Other parts of the nervous system were also affected to varying degrees by the LE, in particular, the brainstem, the cerebellum (in which a loss of nerve cells was also occasionally observed) and the spinal ganglia.

It is manifested by a severe impairment of short-term memory. Anterograde amnesia is often associated with behavioural and psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety, depression, irritability, personality change, acute confusional state, hallucinations and partial or secondary generalised seizures.2 Inaugural status epilepticus is also possible, and can reveal the LE in patient with no particular history or with psychiatric manifestations. However, no case of inaugural status epilepticus is reported in the literature.

LE is usually considered to be herpetic, but recently, other aetiology was described: autoimmune paraneoplastic or non-paraneoplastic.1 However, syphilis is a very rare clinical entity; it has been reported in only a few studies, and only eight cases have been reported in the literature.3

Neurosyphilis refers to an infection of the brain and spinal cord caused by a micro-organism, a spirochaete named Treponema pallidum that is transmitted during sexual intercourse. The infection can occur at any stage of the disease process.4 Clinical neurological manifestations are large and variable, but typically include syphilitic meningitis and cerebral vascular syphilis which translate into a stroke and parenchymal syphilis involving general paralysis, tabes and brain gums.

Cerebral MRI may be normal at an early stage of syphilitic LE, but the pathognomonic lesions are located in the limbic region: mesial temporal lobe, insula and orbitofrontal cortex, and appear hyperintense on T2 and FLAIR without contrast enhancement.5 Over the course of several months, the swelling recedes, while there is constant signal increase. Finally, hippocampal atrophy, compensatory dilation of the temporal horn with persistently increased signalling emerges. This represents the residual (final) stage.

In our case, the patient presented an inaugural status epilepticus, with the CT scan and MRI lesions compatible with the LE. The patient was initially treated as herpes encephalitis regarding imagery outcomes, and lymphocytic meningitis, but this diagnosis was excluded after the negativity of the PCR of herpes simplex virus. A thoraco-abdominopelvic tomography, immunological test and serological test (hepatitis and HIV) were performed to eliminate other aetiologies. The serology of syphilis was strongly positive in blood and CSF. The diagnosis of syphilitic LE was retained, and the patient was treated with doxycycline with a good follow-up.

Early diagnosis of neurosyphilis and appropriate antibiotic treatment make notable clinical improvements. However, the clinical diagnosis of neurosyphilis is often difficult because most patients are asymptomatic or present with non-specific symptoms.

Learning points.

Syphilitic aetiology of limbic encephalitis (LE) should be searched; especially in countries where syphilis is reported more frequently.

An inaugural status epilepticus can reveal LE in a patient with no particular history or with psychiatric manifestations.

Early diagnosis and treatment of syphilis LE will improve the patient, lest the symptoms will stabilise.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hiroshi F, Toshihiro I. Neurosyphilis showing transient global amnesia-like attacks and magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities mainly in the limbic system. Intern Med 2001;40:5–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson NE, Barber PA. Limbic encephalitis—a review. J Clin Neurosci 2008;15:961–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheid R, Voltz R, Vetter T, et al. Neurosyphilis and paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis: important differential diagnoses. J Neurol 2005;252:1129–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeong YM, Hwang HY, Kim HS. MRI of neurosyphilis presenting as mesiotemporal abnormalities: a case report. Korean J Radiol 2009;10:310–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel V, Motala A, Connolly C. Neurosyphilis: a clinico-radiological study. Afr J Neurol Sci 2008;27:73–84 [Google Scholar]