Abstract

A 74-year-old woman with a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was treated with rituximab and CHOP chemotherapy. After three cycles of chemotherapy she developed progressive symptoms of motor imbalance, fatigue, weight loss and impaired cognitive function, which was interpreted as toxicity of the CHOP chemotherapy. The sixth cycle CHOP chemotherapy was withheld and three additional cycles of rituximab were given. Two weeks later, neurological symptoms appeared, including abducens nerve palsy of her left eye, ataxia and hemiparesis of her right body. MRI of the brain revealed two hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images without oedema or gadolinium enhancement. A PCR on John Cunningham (JC) virus DNA in cerebrospinal fluid was negative, but subsequent brain biopsy diagnosed progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). She rapidly deteriorated and died. Awareness of PML during immunosuppressive therapy can be lifesaving, since only immune reconstitution can prevent mortality in these patients.

Background

This case highlights the need for early recognition of neurological symptoms during immunosuppressive treatment, which might be caused by progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). Symptomatic reactivation of John Cunningham (JC) virus almost exclusively occurs in the context of profound immune suppression and is usually fatal. Only treatment directed to reconstitute immune response has proven to be effective. Brain biopsy remains the golden standard in diagnosing (PML), because as shown in our patient, cerebrospinal fluid analysis for JC virus can be negative.

Case presentation

A 74-year-old woman was diagnosed with a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, stadium IV with extranodal involvement of liver and skeleton resulting in a high international prognostic index of 3. Treatment consisted of rituximab in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (R-CHOP) every 2 weeks in addition to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for a total of six R-CHOP cycles and two additional rituximab administrations afterwards.

After the third cycle of R-CHOP the patient and her family mentioned discrete motor weakness and imbalance. Positron emission tomography and CT, performed after four cycles of R-CHOP, showed a complete remission. After the fifth cycle of chemotherapy the patient was admitted to the hospital because of fatigue, weight loss and impaired cognitive function, which was interpreted as toxicity of the CHOP chemotherapy. Therefore, the sixth cycle CHOP of chemotherapy was withheld, but three additional cycles of rituximab were given every 2 weeks according to the protocol. Two weeks after the last rituximab administration, she was readmitted to the neurology department, because of a rapid decline in cognitive function, weight loss, an abducens nerve palsy of her left eye and a hemiparesis of her right body with ataxia.

Investigations

Biochemical and haematological investigations were normal including C reactive protein 6 mg/l (upper limit of normal, 5 mg/l) and leukocyte count 7.4×109/l (normal range, 4.0–11.0×109/l). Serological tests for cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, borrelia burgdorferi and mycoplasma pneumonia were negative. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis revealed a normal white cell count, glucose and total protein and immunophenotyping for monoclonal B cells was negative. Herpes simplex virus DNA, JC virus DNA or varicella zoster virus DNA was not detected in the cerebrospinal fluid by PCR.

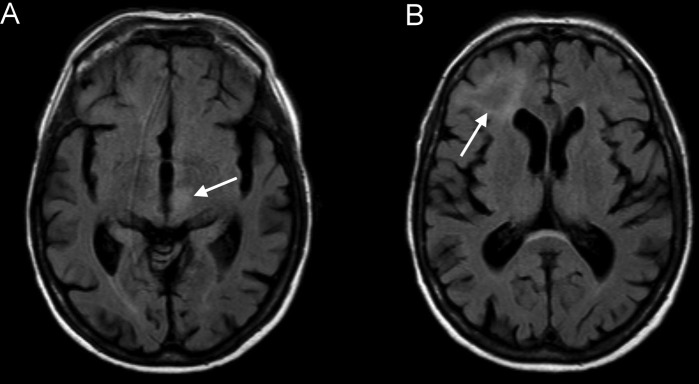

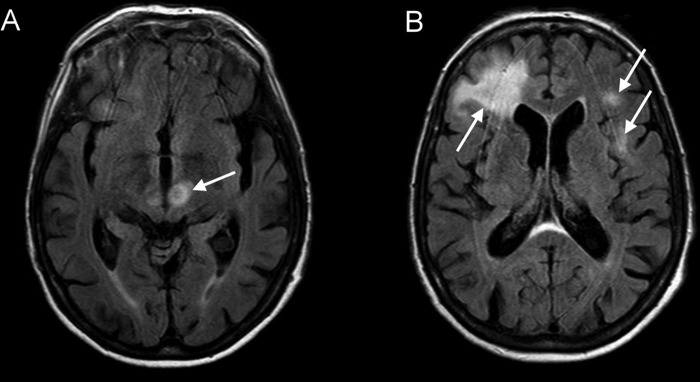

MRI of the brain revealed two hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images (figure 1). Because of rapid clinical deterioration a second MRI was performed about 1 week later showing progression of hyperintense, mostly subcortical lesions without oedema or gadolinium enhancement (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images approximately 3 weeks after the last rituximab administration showing hyperintense lesions in the thalamus/mesencephalon on the left (A) and in the right subcortical frontal lobe (B) without gadolinium enhancement or oedema.

Figure 2.

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images approximately 4 weeks after the last rituximab administration showing progression of the hyperintense, mostly subcortical lesions without enhancement or mass effect (A and B).

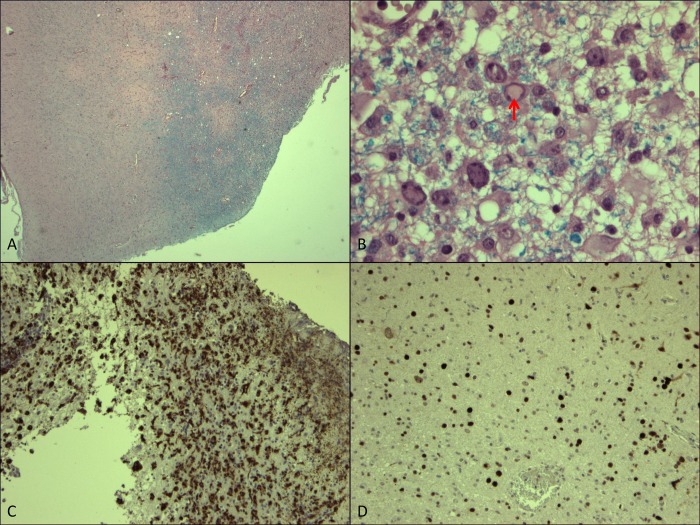

An open biopsy from the right frontal cortex and underlying white matter was obtained (figure 3). Microscopy showed demyelination especially in the white matter (A) with a diffuse infiltrate, mainly composed of lymphocytes and macrophages (C). In the same area reactive astrogliosis could be observed, sometimes with atypia. In various cells homogeneous nuclear inclusions (B) could be observed. Using the SV40 immunohistochemical staining procedure (D), JC virus could be demonstrated extensively in this biopsy and PML was diagnosed.

Figure 3.

(A) Overview of the biopsy with the cortex on the left and on the right the white matter. This Luxol Fast Blue staining shows a loss of myelin, especially at the top of this picture (amplification ×25). B: Detail from (A) showing reactive gliosis and in the middle a cell with a viral nuclear inclusion (arrow) (amplification ×400). C: Immunohistochemical staining for CD68 (PGM1 clone) showing the heavy infiltrate of macrophages (amplification ×50). D: Immunohistochemical staining for SV40 showing all the cell nuclei positive for JC virus (amplification ×50).

Differential diagnosis

There were no signs of inflammation. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis revealed no pleocytosis or high total protein, which made an encephalitis, vasculitis or acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis less likely. A secondary central nervous system lymphoma was also less likely, since immunophenotyping for monoclonal B-cells was negative and our patient was in complete remission after four cycles of R-CHOP. Furthermore, none of the aforementioned viruses could be detected which made an encephalitis even more unlikely. MRI revealed no contrast enhancement or oedema, thereby excluding other brain tumors or metastases from other malignancies. Because of these results and the rapid clinical decline, PML seemed most reasonable and histological examination of brain biopsy revealed features, characteristic of PML.

Treatment

There is no specific antiviral drug against JC virus. Current treatment therefore consists of restoring immune response to JC virus for control of the infection. However, the symptoms in our patient were interpreted as toxicity of the CHOP chemotherapy and particularly the high dose of prednisolone. Therefore, administration of rituximab was continued resulting in ongoing immune suppression and clinical deterioration of the patient. Once the diagnosis of PML was confirmed by brain biopsy, the patient was in a vegetative state and only received supportive care.

Outcome and follow-up

Histological examination of the brain biopsy demonstrated JC virus, extensively in the biopsy and PML was diagnosed. Our patient deteriorated and died in less than 4 weeks after confirmed diagnosis of PML and 2 months after the last rituximab administration.

Discussion

PML is a rare and usually fatal demyelinating disease of the central nervous system caused by lytic infection of oligodendrocytes with JC virus.1 2 This lytic infection of oligodendrocytes by JC virus leads to subsequent cell death, demyelination and loss of cerebral tissue.3 PML is caused by the reactivation of latent JC virus and usually occurs in immunocompromised patients.1–4 Impaired T-cell function is sufficient for JC virus reactivation. PML has therefore been reported in patients with HIV, haematological malignancies, such as chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, autoimmune disorders and after haematopoietic or solid-organ transplantation.5 Furthermore, PML has been observed after treatment with monoclonal antibodies, such as rituximab, natalizumab and efalizumab.2 4

Primary JC virus infection is asymptomatic in healthy individuals, and is usually acquired during childhood by oral or respiratory routes.6 The primary infection by JC virus is probably engaging the tonsils and parapharyngeal lymph nodes and is disseminated by the tonsillar B lymphocytes to the kidney, spleen, lung, lymph node and bone marrow, where it is dormant until the development of an immunosuppressive state that permits JC virus mutation, reactivation, replication and invasion of the central nervous system.4 6 7 Serum antibodies against JC virus are detected in more than 50% of the adult population.4 6

Diagnosis of PML is based on clinical symptoms, neuroimaging findings and neuropathological findings. Clinically, the disorder presents subacutely with cognitive impairment, motor symptoms, speech difficulties and symptoms of visual field deficits.2 6 7 Neurological signs and symptoms of PML depend on the location of the lesions in the central nervous system.8 The disease does not usually involve the optic nerves or spinal cord.2 MRI demonstrates bilateral, asymmetric lesions, usually in the subcortical white matter, which are hypointense on T1-weighted images, and hyperintense on T2-weighted and FLAIR images.2 7 The lesions usually showed no gadolinium enhancement or oedema and are well demarcated.7 The affected brain lesions do not correspond to specific vascular territories.2 Definitive diagnosis of PML is a brain biopsy with nearly 100% specificity and sensitivity.9 An alternative to brain biopsy is a PCR for JC virus in the cerebrospinal fluid. However, reported sensitivity is only 75% whereas specificity is high, nearly 100%.1 Because of the highly variable concentration of viral load in cerebrospinal fluid, JC virus-negative PCR analysis can occur in a patient with biopsy-confirmed PML, which was also the case in our patient.9

There is no specific antiviral drug against JC virus. A few antiviral drugs have been investigated for treatment against PML. Cytarabine has been used by intrathecal or intravenous administration, since it has one of the highest in vitro activities against JC virus replication, but survival benefit could not be determined.1 2 Serotonin receptor antagonists have also been proposed as agents potentially blocking JC virus entry, since the serotonergic 5-HT2α receptor is discovered to be involved in JC virus internalisation into glial cells.10 However, evidence of efficacy is still scarce.2 10 Mefloquine, an antimalarial drug, could inhibit JC virus replication in a cell culture system and might be effective.2 Although this still needs to be assessed. Incidental recovery with aforementioned treatments is reported.1 5

Since PML predominantly occurs in immunocompromised patients, current treatment consists of restoring immune response to JC virus for control of the infection. Susceptibility to JC virus reactivation in patients receiving rituximab therapy may be explained by the fact that functioning B cells are required for an optimal T-cell response. Whether or not early detection of PML and restoring immune response in our patient would have led to stabilisation or improved outcome remains unknown. In a study, reporting 57 cases of PML after rituximab therapy, which included 52 patients with B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, a case death rate of 100% was found among PML cases diagnosed within 3 months after the last rituximab dose.11

This case should remind physicians that neurological symptoms during immunosuppressive treatment might be caused by PML. Early diagnosis of PML and immediate withdrawal of immunosuppressants are necessary to restore immune response against JC virus and might therefore lead to a better clinical outcome.

Learning points.

Consider progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) when neurological symptoms appear during immunosuppressive therapy.

A negative PCR on JC virus DNA in cerebrospinal fluid does not exclude PML.

Brain biopsy is the golden standard for diagnosis of PML.

Current treatment consists of restoring immune response to JC virus.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Pelosini M, Focosi D, Rita F, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: report of three cases in HIV-negative hematological patients and review of literature. Ann Hematol 2008;87:405–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan CS, Koralnik IJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and other disorders caused by JC virus: clinical features and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:425–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freim Wahl SG, Folvik MR, Torp SH. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a lymphoma patient with complete remission after treatment with cytostatics and rituximab: case report and review of the literature. Clin Neuropathol 2007;26:68–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paues J, Vrethem M. Fatal progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with rituximab. J Clin Virol 2010;48:291–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carson KR, Focosi D, Major EO, et al. Monoclonal antibody-associated progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in patients treated with rituximab, natalizumab, and efalizumab: a review from the research on adverse drug events and reports (RADAR) Project. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:816–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger JR. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and newer biological agents. Drug Saf 2010;33:969–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keene DL, Legare C, Taylor E, et al. Monoclonal antibodies and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Can J Neurol Sci 2011;38:565–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engsig FN, Hansen AB, Omland LH, et al. Incidence, clinical presentation, and outcome of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in HIV-infected patients during the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: a nationwide cohort study. J Infect Dis 2009;199:77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drews K, Bashir T, Dorries K. Quantification of human polyomavirus JC in brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy by competitive PCR. J Virol Methods 2000;84:23–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuccori M, Focosi D, Maggi F, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: a report of three cases in HIV-negative patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphomas treated with rituximab. Ann Hematol 2010;89:519–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carson KR, Evens AM, Richey EA, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after rituximab therapy in HIV-negative patients: a report of 57 cases from the research on adverse drug events and reports project. Blood 2009;113:4834–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]