Abstract

A 30-year-old Filipino man presented with a 11-year history of coarse facial features and progressive enlargement of hands and feet. Initial work-up revealed elevated insulin-like growth factor-1 and non-suppressible growth hormone level after 75 g glucose challenge test. Initial cranial MRI performed in the year 2010 showed absence of pituitary adenoma. The patient was lost to follow-up. He again consulted in the year 2011 and a repeat cranial MRI and a dedicated pituitary MRI were performed and both did not reveal any pituitary mass. Further investigation included chest and abdominal CT scan, both of which did not show any neoplasm. At present, there has been no practice guideline on the management of acromegalic patients on whom the identifiable source cannot be found. The patient was given the option to undergo surgical exploration of the pituitary gland or medical treatment with somatostatin analogues. He decided to undergo surgery but has not given consent for the procedure.

Background

Acromegaly is caused by abnormally elevated levels of growth hormone (GH) and secondary increases in insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). The source of excessive GH must be identified to adequately manage the case. At present, there has been no practice guideline on how to manage acromegalic patients on whom the identifiable source cannot be found.

Case presentation

The patient is a 30-year-old Filipino man who presented with a 11-year history of coarse facial features and progressive enlargement of hands and feet. There were no headaches, dizziness and blurring of vision. There was also chest pain, easy fatigability, difficulty breathing, snoring or deepening of voice. He did not complain of polyuria, nocturia and polydipsia. There were no bowel changes. The patient consulted because of abnormal facial features.

Prior to the consultation, there was no identifiable comorbid illness. There was also no prior hospitalisation. The family history revealed that the patient has another sibling with the same coarse facial features but has never been treated.

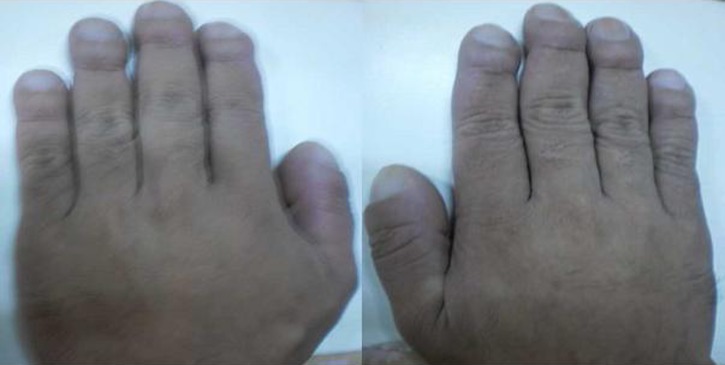

On physical examination, his height was 1.70 m and his weight was 65 kg with a calculated body mass index of 22.44 kg/m2. Blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and temperature were all normal. Coarse facial features included enlarged frontal and nasal bone, thickened facial and scalp skin including the periorbital area and thickened lips. His upper incisors are noted to be spread apart. Funduscopic examination revealed the absence of papilloedema. Hands and feet are noted to be enlarged but non-oedematous. The rest of the physical examination findings were all unremarkable (figures 1–3).

Figure 1.

Coarse facial features (enlarged frontal and nasal bone, thickened facial and scalp skin including the periorbital area, thickened lips).

Figure 2.

Enlarged hands.

Figure 3.

Enlarged feet.

Investigations

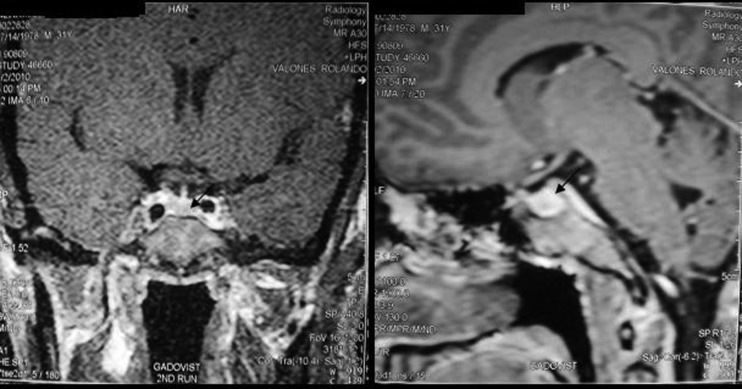

Initial laboratory tests performed in the year 2010 showed elevated IGF-1 at 1375 ng/ml (normal range: 117–329) and non-suppressible GH level after 75 g glucose challenge test with a baseline result of 3.7 IU/ml (normal range: 0–14) and after 2 h of 8.6 IU/ml (expected result: <1). Free T4 was 20.4 pmol/l (normal range: 11–24), serum 08:00 cortisol was 400.1 nmol/l (normal range: 166–620) and prolactin was 231.6 uIU/ml (normal range: 80–500). Cranial MRI showed the absence of mass or hyperplastic changes (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cranial MRI which revealed normal result. Arrow pointing to the normal pituitary gland.

The patient was lost to follow-up for 1 year. There were no new symptoms noted.

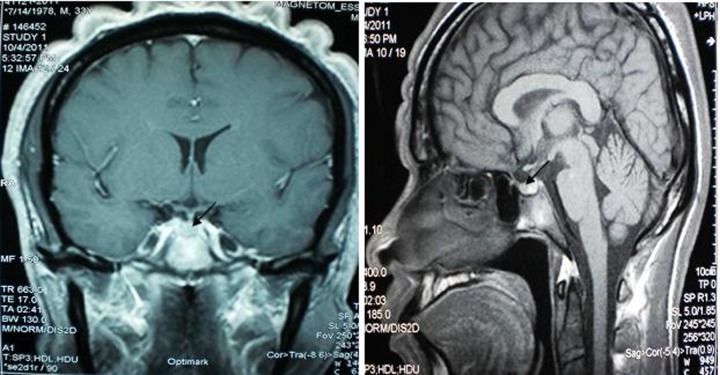

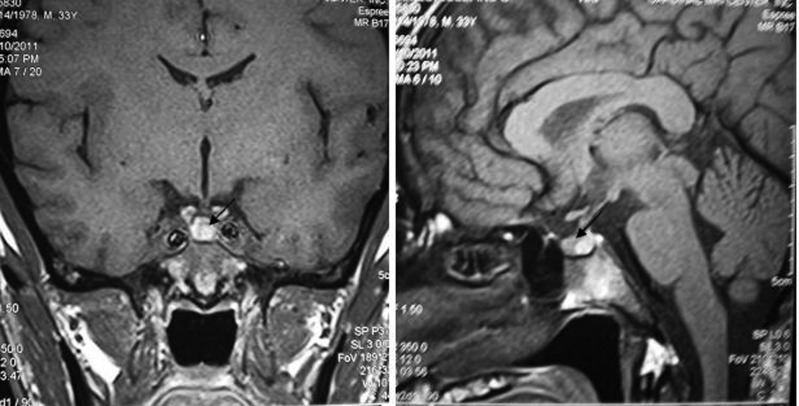

On his consultation in the year 2011, free T4 was 16.6 pmol/l (normal range: 11–24), thyroid-stimulating hormone was 1.2 mIU/l (normal range: 0.25–4), serum 08:00 cortisol was 362.3 nmol/l (normal range: 166–620), prolactin was 238.3 uIU/ml (normal range: 80–500), follicle-stimulating hormone was 1.3 mIU/l (normal range:1–10.5), luteinising hormone was 2.8 mIU/l (normal range: 1.9–9.4) and testosterone was 51.7 nmol/l (normal range: 8.5–64)—all of which were normal. Determination of serum IGF-1 and serum GH during a 75 g glucose tolerance test was not repeated since there were no changes in the patient’'s clinical features. Repeat cranial MRI did not show any pituitary mass. To demonstrate the possibility of a small pituitary mass (<2 mm) which cannot be seen on conventional cranial MRI, a dedicated pituitary MRI was also performed which again revealed normal result. Work-up for ectopic sources was then pursued. Chest and abdominal CT scans were both performed and no neoplasm was seen in these imaging tests. The complete blood count, serum sodium and potassium, fasting blood sugar, 2 h postprandial blood sugar, lipid profile, electrocardiogram and urinalysis were all normal (figures 5–8).

Figure 5.

Repeat cranial MRI which did not show any pituitary mass. Arrow pointing to the normal pituitary gland.

Figure 6.

Dedicated pituitary MRI which did not show any pituitary mass. Arrow pointing to the normal pituitary gland.

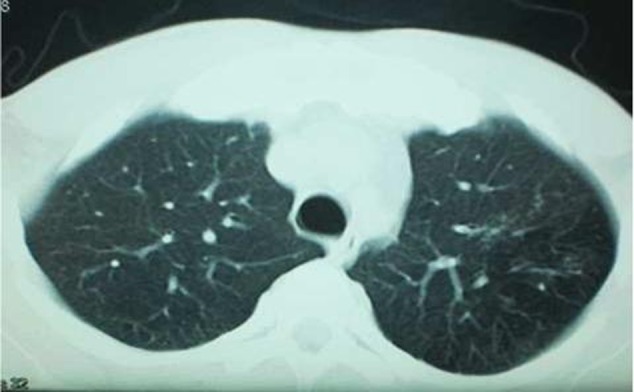

Figure 7.

Chest CT scan which did not show any neoplasm.

Figure 8.

Abdominal CT scan which did not show any neoplasm.

Differential diagnosis

For patients with acromegaly, the source of excessive GH should be identified. The most common is GH-secreting pituitary adenoma. Rare causes would include a growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH)-secreting tumour in the hypothalamus and ectopic GH-secreting tumours in the chest and abdomen.

Treatment

At present, there is no standard practice guideline for the management of a patient with an unidentifiable cause of acromegaly. After conferring with experts from the USA (Dr Shlomo Melmed and Ariel Barkan), the patient was advised to have an intraoperative surgical exploration of the pituitary gland and resect if there is mass. A somatostatin analogue can be offered to the patient if he will not consent for surgery.

Outcome and follow-up

Both surgical and medical treatment options were offered to the patient and he opted to undergo surgery. He decided to undergo surgery but has not given consent for the procedure. Aside from financial constraints, the patient decided to settle a family dispute before undergoing the surgical procedure.

Discussion

How common is this?

Acromegaly is an uncommonly diagnosed disorder with an annual estimated incidence of three to four cases per one million people.1 Greater than 95% of acromegaly cases are caused by a benign GH-secreting pituitary adenoma (involving somatotroph cells). Less than 5% of acromegaly cases will be caused by an ectopic source, including ectopic secretion by an ectopic GHRH tumour, a hypothalamic secreting GHRH tumour or an ectopic GH-secreting tumour.2 It may also occur as a component of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes, including the Carney complex or MEN-1. The Carney complex consists of myxomas, spotty skin pigmentation and testicular, adrenal and pituitary tumours. About 20% of patients with this autosomal-dominant syndrome associated with chromosome 2p16 harbour GH-secreting adenomas.3 MEN-1, also an autosomal-dominant syndrome, consists of hyperplastic or adenomatous parathyroid glands, endocrine pancreas and anterior pituitary.4 Isolated familial acromegaly or gigantism not associated with MEN has rarely been reported.5 6 Low prevalence germline mutations of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein (AIP, located on 11 q 13.3) gene were reported as predisposing to a subset of patients with familial acromegaly and gigantism;7 15% of families with isolated familial acromegaly exhibit AIP mutations, and tumours are encountered earlier in subjects harbouring a mutation.8 9 Familial acromegaly is a possibility in this case since the patient mentioned is having a brother with similar features. This sibling, however, has not presented to us for medical evaluation.

Acromegaly can also be caused by GH-secreting pituitary adenomas that are not evident on conventional MRI. There were previous reports of patients with GH-secreting pituitary adenoma and negative MRI. In 1990, Doppman et al10 described three acromegalic patients in whom MRI failed to demonstrate a pituitary adenoma that was later discovered at surgery (resected adenoma sizes, 6, 7 and 10 mm). Complete resection and remission were attained in all three patients. In 2009, Daud et al11 described an acromegalic patient who did not show imaging evidence of a pituitary adenoma despite MRI with and without contrast, including thin-cut spoiled-gradient recalled imaging. Surgical exploration was performed on the patient, and a 9 mm adenoma was discovered and resected, leading to remission in biochemical parameters. In 2010, Lonser et al12 reported that out of 190 patients, 6 (3 male patients, 3 female patients; 3.2% of all patients) with suspected GH-secreting adenomas did not demonstrate imaging evidence of pituitary adenoma on conventional MRI. Three patients underwent a postcontrast, volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination MRI sequence (1.2 mm slice thickness), which revealed a 4 mm pituitary adenoma not seen on the spin echo T1-weighted MRI in one patient. A pituitary adenoma was identified and removed in all patients (mean diameter: 5.6 mm; range: 5–6.7 mm). Histological analysis confirmed that the lesions were GH-secreting adenomas. All patients achieved biochemical remission after surgical resection.

Management guidelines

At present, there is no standard practice guideline for the management of a patient with an unidentifiable cause of acromegaly. Most of the previous reports have managed the patient with intraoperative surgical exploration of the pituitary gland and subsequent resection of the adenoma if there is an identifiable one. Since the morbidity and mortality associated with resection of microadenomas are low and the possibility of immediate biochemical remission is excellent, surgical exploration in cases of MR-invisible GH-secreting pituitary adenomas is a reasonable approach in the management of acromegalic patients without evidence of an ectopic aetiology of acromegaly.12

Learning points.

Among patients with acromegaly, it is important to identify the source of excessive growth hormone (GH) secretion. Difficulty arises when imaging tests are not able to visualise the source of GH excess.

At present, there is no standard practice guideline for management of acromegalic patients without an identifiable source of excessive GH production.

Surgical exploration in cases of magnetic resonance-invisible GH-secreting pituitary adenoma without evidence of ectopic aetiology is a reasonable management option.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cook D, Ezzat S, Katznelson L, et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of acromegaly. Endocr Pract 2004;10:213–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chanson P, Salenave S. Acromegaly. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2008;3:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stratakis CA, Carney JA, Lin JP, et al. Carney complex, a familial multiple neoplasia and lentiginosis syndrome: analysis of 11 kindreds and linkage to the short chromosome 2. J Clin Invest 1996;97:699–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teh BT, Kytola S, Farnebo F, et al. Mutation analysis of the MEN 1 gene in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, familial acromegaly and familial isolated hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:2621–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benlian P, Giraud S, Lahlou N, et al. Familial acromegaly: a specific clinical entity: further evidence from the genetic study of a three-generation family. Eur J Endocrinol 1995;133:451–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ackermann F, Krohn K, Windgassen M, et al. Acromegaly in a family without mutation in the menin gene. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 1999;107:93–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vierimaa O, Georgitsi M, Lehtonen R, et al. Pituitary adenoma predisposition caused by germline mutations in the AIP gene. Science 2006;312:1228–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daly AF, Vanbellinghen JF, Khoo SK, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein gene mutations in familial isolated pituitary adenomas: analysis in 73 families. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:1891–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Georgitsi M, Raitila A, Karhu A, et al. Molecular diagnosis of pituitary adenoma predisposition caused by aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein gene mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:4101–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doppman JL, Miller DL, Patronas NJ, et al. The diagnosis of acromegaly: value of inferior petrosal sinus sampling. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1990;154:1075–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daud S, Hamrahian AH, Weil RJ, et al. Acromegaly with negative pituitary MRI and no evidence of ectopic source: the role of transphenoidal pituitary exploration? Pituitary 2011;14:414–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lonser R, Kindzelski B, Mehta G, et al. Acromegaly without imaging evidence of pituitary adenoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:4192–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]