Abstract

The transcription factor Bcl-6 orchestrates the germinal center reaction through its actions in B and T cells, and regulates inflammatory signaling in macrophages. We report that genetic replacement by mutant Bcl-6, which cannot bind corepressors to its BTB domain, disrupted germinal center formation and immunoglobulin affinity maturation, due to a defect in B cell proliferation and survival. In contrast, BTB loss of function had no effect on T follicular helper cell differentiation and function, nor other T helper subsets. Bcl6 null mice displayed a lethal inflammatory phenotype, whereas BTB mutant mice experienced normal healthy lives with no inflammation. Bcl-6 repression of inflammatory responses in macrophages was accordingly independent of the BTB domain repressor function. Bcl-6 thus mediates its actions through lineage-specific biochemical functions.

INTRODUCTION

Bcl-6 is a transcriptional repressor, originally identified as encoded by a frequently translocated locus in diffuse large B cell lymphomas (DLBCLs)1. In normal development Bcl-6 plays critical functions in various cell types within the adaptive and innate compartments of the immune system. Bcl-6 is highly up-regulated in B cells after T cell-dependent (TD) antigenic challenge2, and is required for formation of germinal centers (GCs) within which B cells undergo immunoglobulin affinity maturation. Bcl-6-deficient (Bcl6−/−) mice fail to form GCs and hence are unable to generate high-affinity antibodies3–5. The proposed biological function of Bcl-6 within GC B cells is to facilitate simultaneous rapid proliferation and tolerance of genomic damage occurring during clonal expansion and somatic hypermutation through directly repressing DNA damage sensing and checkpoint genes such as ATR6, CHEK1 (ref. 7), EP300 (ref. 8), TP53 (ref. 9) and CDKN1A10. Follicular helper T (TFH) cells, specifically GC TFH cells, are specialized CD4+ helper cells that provide help to B cells during the GC reaction11, 12. Bcl-6 is up-regulated during TFH cell differentiation and Bcl6−/− T cells fail to differentiate into TFH cells in vivo13–15. Constitutive expression of Bcl-6 enhances TFH cell differentiation14–16. The requirement for Bcl-6 in both GC B cells and TFH cells is cell autonomous, and loss of Bcl-6 in either cell type leads to abrogation of the GC reaction17. Bcl-6 also plays an important role in macrophages, where it mediates a dampening effect on inflammatory signaling through repression of chemokine expression and NF-κB target genes18, 19. Bcl6−/− mice present with a lethal inflammatory disease caused by the interplay and crosstalk between macrophages and T helper cells.

Bcl-6 is a member of the BTB-zinc finger family of proteins. Its BTB domain forms an obligate homodimer and it contains C2H2 zinc fingers that bind to DNA. The interface between Bcl-6 BTB monomers creates two symmetrical extended lateral grooves that form docking sites for the corepressor proteins SMRT, NCOR and BCOR20–22. These three corepressors bind to Bcl-6 through an unstructured 18 amino acid Bcl-6-binding domain (BBD)23. The BBDs of NCOR and SMRT are identical, whereas the BCOR BBD is completely different, yet all three bind to the Bcl-6 BTB lateral groove in perfectly overlapping configurations23, 24. The dual Bcl-6 BTB domain point mutations N21K (asparagine 21 to lysine) and H116A (histamine 116 to alanine) completely abrogate binding of Bcl-6 to NCOR, SMRT and BCOR without impairing folding and dimerization23. The N21K, H116A mutant Bcl-6 BTB domain is completely inactive, indicating that the lateral groove-BBD interface explains the repressor activity of the Bcl-6 BTB domain23. However, Bcl-6 also contains a middle autonomous repression region often called RD2 (repression domain 2)25, which may recruit other corepressors, such as NuRD and CTBP26, 27. The reported Bcl-6 consensus binding site TTCCT(A/C)GAA overlaps with STAT transcription factor binding sites25, 28, 29, and several lines of evidence indicate that Bcl-6 may antagonize STAT signaling, with potential relevance to inflammatory and innate immunological functions3, 30, 31.

Collectively, the data suggest interlocking biological roles for Bcl-6 in the immune system. However the link between the transcriptional mechanisms of action of Bcl-6 with its biological actions in the immune system remains unknown. Here we generated a knockin mouse model in which the endogenous Bcl6 locus encodes a mutant form of the protein containing the N21K and H116A point mutations. The fact that SMRT, NCOR and BCOR are co-expressed with Bcl-6 in the relevant cell types and that the BTB domain mechanism is the only well-characterized biochemical function of Bcl-6 favors the notion that the biological readout of such a knockin model would be most rigorously interpretable. Remarkably, the data suggest that Bcl-6 transcriptional mechanisms of action are lineage and biological function specific, with important implications for our general understanding of how Bcl-6 and other transcription factors work, as well as for the clinical translation of Bcl-6 inhibitors.

RESULTS

Bcl6 BTB N21K and H116A mutant knockin mice are viable

To address the biological function of Bcl-6 BTB domain-corepressor interactions in vivo, we introduced point mutations in exon 3 and exon 4 of Bcl6, resulting in the desired N21K and H116A substitutions in the BTB domain (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). Heterozygotes for the Bcl6BTBN21K,H116A-neomycin resistance (neor) allele were crossed to EIIa-Cre transgenic mice to generate heterozygous Bcl6BTBN21K,H116A animals (Bcl6BTBMUT hereafter), and then intercrossed to generate homozygous BTB mutant mice (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Bcl6BTBMUT mice were born at expected Mendelian ratios, were viable and developmentally indistinguishable from wild-type littermates (whereas in marked contrast Bcl6−/− mice are runted, sickly and born at lower than expected ratios). Quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblotting revealed normal expression of mutant Bcl6 transcript and protein from splenic B220+ cells of Bcl6BTBMUT mice (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Sequencing of tail genomic DNA from Bcl6BTBMUT mice confirmed the presence of the introduced point mutations (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Quantitative ChIP assays showed that Bcl-6BTBMUT protein retained the same ability to bind target genes in cultured macrophages as wild-type Bcl-6 protein (Supplementary Fig. 2d). The abundance of SMRT at Bcl-6 target genes in Bcl6BTBMUT was identical to Bcl6−/− mice, confirming that these lateral groove mutations abrogate interaction with lateral groove binding corepressors. Bcl6N21K,H116A mutant alleles thus encoded a viable transcription factor able to bind to its targets but unable to recruit corepressors through the BTB domain.

GC formation is impaired in Bcl6BTBMUT mice

Phenotypic analysis revealed normal early B cell development in the bone marrow and spleens of Bcl6BTBMUT mice as well as normal peripheral T cell distributions (Supplementary Figs. 3a–c). Bcl6BTBMUT mice also formed normal splenic primary lymphoid follicles (data not shown). Analysis of spontaneous formation of GCs in spleens of unimmunized mice by peanut agglutinin (PNA) staining revealed few small GCs scattered in wild-type mice, whereas none were observed in Bcl6BTBMUT mice (data not shown). After immunization with sheep red blood cells (SRBCs), a T cell-dependent antigen, Bcl6BTBMUT mice only developed few, scattered and small PNA- and Bcl-6-positive cell clusters (Fig. 1a). Serial examination of GCs by immunohistochemistry at days 7, 10 and 14 after SRBC immunization showed a marked reduction in GC size and number at all three time points in Bcl6BTBMUT mice (Fig. 1b,c). Lymph nodes in Peyer’s patches revealed similar loss of GCs and presence of residual cell clusters in Bcl6BTBMUT mice (Supplementary Fig. 4a), emphasizing the general requirement for Bcl6 BTB-mediated repression in GC formation.

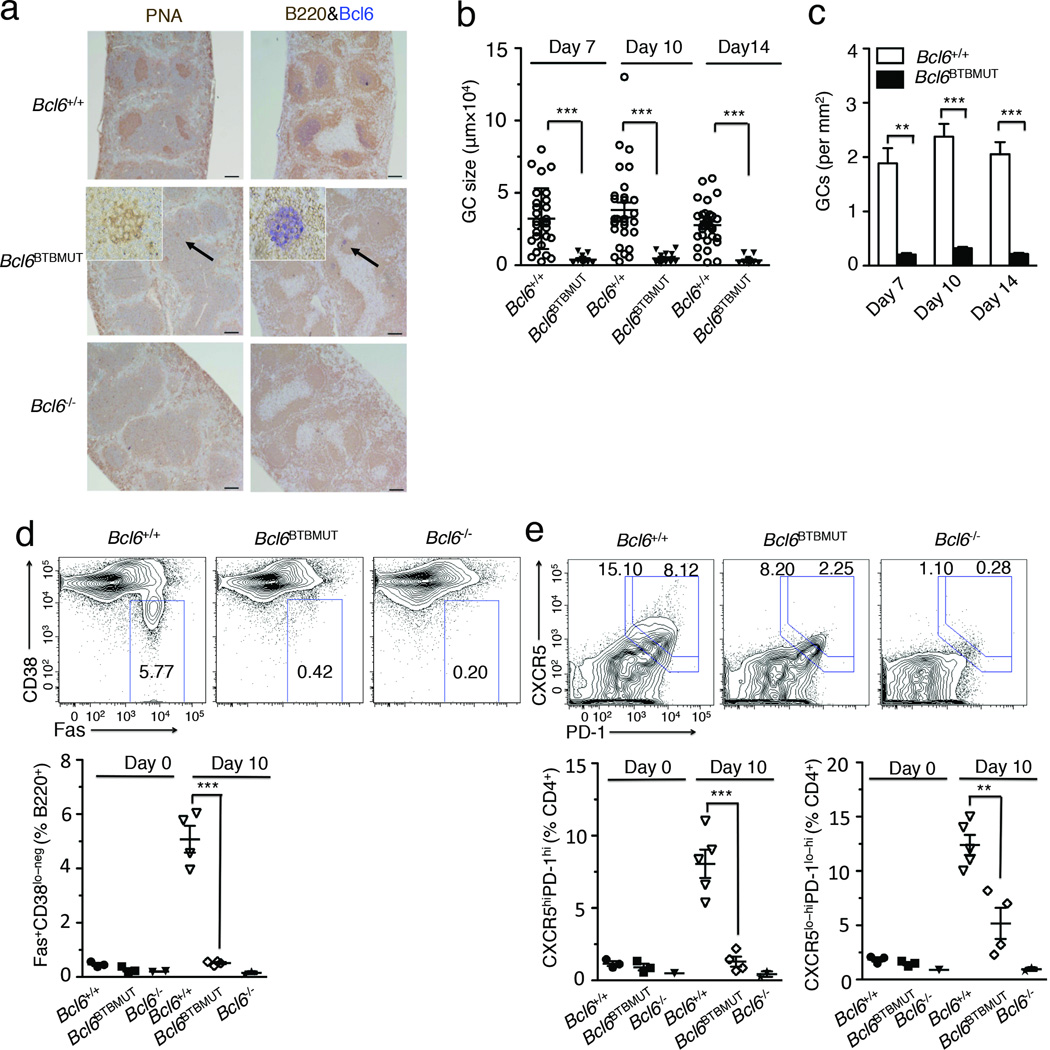

Figure 1. Bcl6BTBMUT knock-in mice markedly reduce germinal centers.

(a) Immunohistochemistry of paraffin-embedded serial spleen sections from mice 10 d after immunization with SRBCs. Scale bars, 200 µm. GCs in Bcl6BTBMUT sections were indicated by arrows and shown as inset (original magnification, ×20). Data are representative of over five experiments. (b,c) The size (b) and numbers (c) of GCs in spleen sections of mice 7 d, 10 d and 14 d after immunization with SRBCs. Individual dot represents each GC. Results are from three independent experiments (means and s.e.m. of three mice). (d) Flow cytometric contour plots of GC B cells (FAS+ CD38lo-neg, boxed) gated on live B220+ splenic lymphocytes from mice 10 d after immunization with SRBCs. Bottom, quantification of GC B cells as percent of live B220+ cells in mice before and 10 d after immunization. (e) Flow cytometric contour plots of GC TFH cells (CXCR5hi PD1hi, boxed) and total TFH cells (CXCR5lo-hiPD-1lo-hi, boxed) gated on live B220−CD4+ splenic lymphocytes from mice 10 d after immunization with SRBCs. Bottom, quantification of GC TFH and TFH cells as percent of live B220−CD4+ cells. Each symbol represents an individual mouse (d,e). Data are representative of three independent experiments (error bars, s.e.m. of two to five mice). ** P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 (two-tailed t-test).

To better understand the mechanism of GC impairment in Bcl6BTBMUT mice, we first compared the frequency of GC B cells (CD38lo-negFas+B220+) in splenic B cells from wild-type, Bcl6−/− and Bcl6BTBMUT mice before and at day 10 after SRBCs immunization. The frequency of GC B cells in unimmunized wild-type mice was 0.38±0.14%, and the numbers increased to 5.07±0.85% ten days after immunization (Fig. 1d). As previously reported, GC B cells were essentially undetectable in Bcl6−/− mice before and after immunization (<0.2%). Likewise, Bcl6BTBMUT mice displayed almost complete loss of GC B cells with 0.23 ± 0.09% prior to immunization and 0.57±0.068% at day 10 post-immunization (Fig. 1d).

We next examined the development of TFH (CXCR5lo-hiPD1lo-hi) and GC TFH (CXCR5hiPD1hi), which locate to GCs. The frequency of GC TFH in splenic CD4+ cells was markedly reduced in immunized Bcl6BTBMUT as compared to wild-type mice (2±0.3% versus 8.05±1.9%, Fig. 1e). The proportion of CXCR5loPD1lo TFH cells, a population that includes pre-GC TFH cells, was also reduced in Bcl6BTBMUT mice. Accordingly total TFH cells, composed of GC TFH and CXCR5loPD1lo TFH, were significantly reduced in Bcl6BTBMUT mice (Fig. 1e). Similar defects were observed in Bcl6BTBMUT mice challenged with a second T-cell dependent antigen 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl conjugated to chicken gamma globulin (NP-CGG, Supplementary Fig. 4b). Collectively, these results demonstrate that BTB domain-mediated transcriptional repression is absolutely required for GC formation.

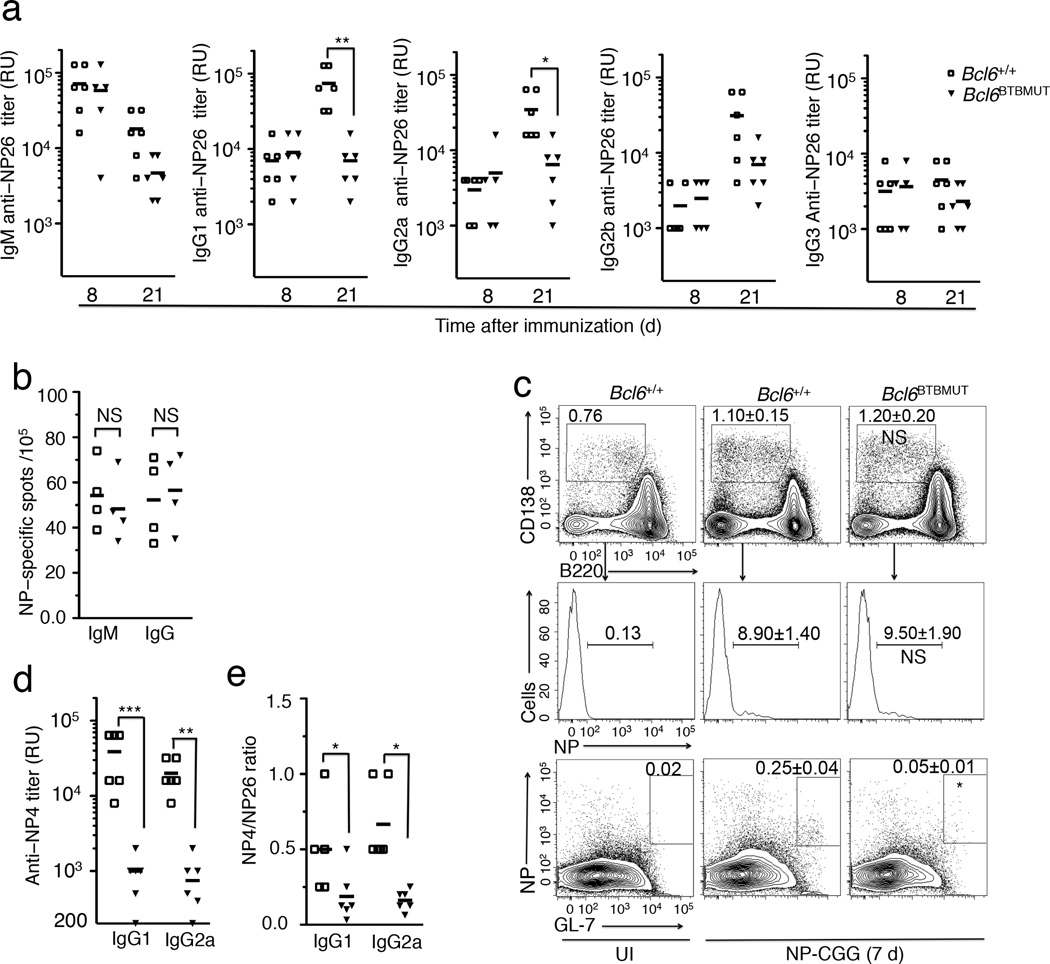

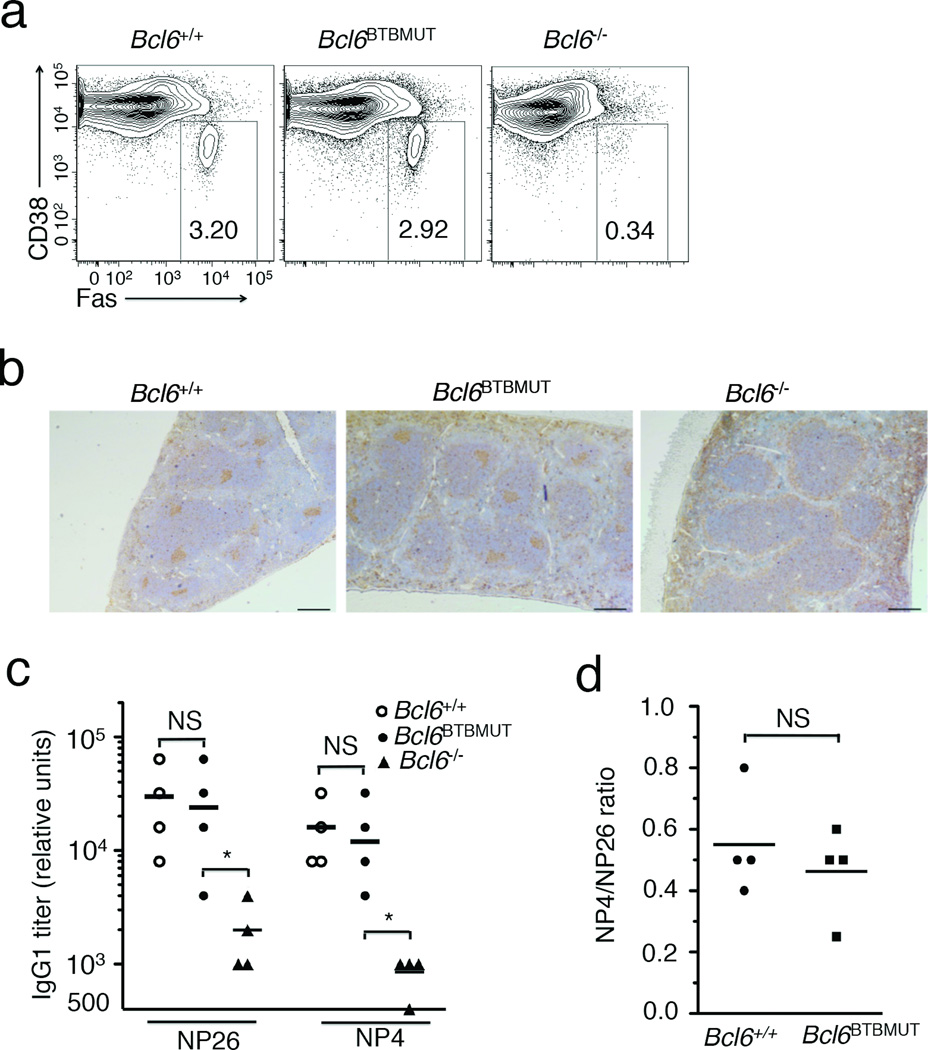

Impaired immunoglobulin affinity maturation in Bcl6BTBMUT mice

Bcl-6 is not required for T cell-independent antigen response and accordingly Bcl6BTBMUT mice displayed normal low-affinity antibody responses to T cell-independent antigen NP-Ficoll (data not shown). The T cell-dependent B cell immune response triggers both an extrafollicular response generating short-lived plasma cells and an early wave of low affinity antibody production, and a GC response, which gives rise to long-lived plasma or memory cells, and a later wave of high-affinity antibodies. Immunization with NP-CCG induced a normal extrafollicular response in Bcl6BTBMUT mice, with the expected production of low-affinity immunoglobulin specific to bind NP26-BSA (Fig. 2a). By contrast, at day 21 after immunization the titers of anti-NP-specific IgG1 and IgG2a were significantly reduced in Bcl6BTBMUT as compared to wild-type mice, with a trend towards lower titers of other immunoglobulins (Fig. 2a). Bcl6BTBMUT mice also formed a similar number of early (7 d) antigen-specific IgM- and IgG-secreting cells (Fig. 2b) and plasma cells (NP+CD138+CD11c−CD4−CD8−B220lo/−, Fig. 2c). However, at this time point antigen-specific GC B cells (NP+GL7+B220+) in Bcl6BTBMUT mice were less than 20% of wild-type controls (Fig. 2c). High-affinity IgG1 and IgG2a able to bind NP4-BSA, which recognizes high-affinity immunoglobulin, were also markedly reduced in immunized Bcl6BTBMUT mice (Fig. 2d), indicating impaired affinity maturation. This defect was also evident by calculating the ratio of IgG1 and IgG2a titers detected with NP4-BSA to those with NP26-BSA (Fig. 2e). Recruitment of co-repressors by the BTB domain is therefore indispensable for Bcl-6 to drive T cell-dependent formation of high-affinity immunoglobulin.

Figure 2. Intact extrafollicular, but impaired germinal center responses in Bcl6BTBMUT mice.

(a) Titers of NP-specific immunoglobulin were measured using NP26-BSA in sera of mice 8 d and 21 d after immunization with NP-CGG. RU, relative units. (b) The frequency of NP-specific IgM and IgG secreting cells among splenocytes in mice 7 d after immunization with NP-CGG, assessed by ELISPOT. (c) Flow cytometry for CD138 and B220 expression on live CD11c−CD4−CD8− spleen cells (top). Small box inserts outline total plasma cells (CD138+B220lo-negCD11c−CD4−CD8−). NP-positive compartment is further gated on total plasma cells (middle). NP-specific GC B cells (NP+GL7+, boxed) are gated on live splenic B220+ cells (bottom). Data are shown as means±s.e.m of three mice. P values were calculated by comparing total plasmas (top), NP+ plasmas (middle) and NP+ GC B cells in Bcl6BTBMUT to those in wild-type. UI, unimmunized. (d) Titers of NP-specific IgG1 and IgG2a measured using NP4-BSA in sera of mice 21 d after immunization with NP-CGG. (e) Ratio of the titers of IgG1 and IgG2a detected with NP4-BSA to those with NP26-BSA. In a, b, d and e, open squares and filled triangles represent wild-type and Bcl6BTBMUT mice. Small horizontal lines indicate means and date are from three independent experiments with four to six mice. NS, not significant; *P<0.05; **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 (two-tailed t-test).

GC impairment in Bcl6BTBMUT mice is B cell-intrinsic

Bcl6−/− mice display cell autonomous defects in both GC B and TFH cells4, 5, 13–15. To determine whether Bcl6BTBMUT mice present similar defects, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeras by transplanting a mixture of congenic CD45.1+ wild-type bone marrow cells (50%) together with CD45.2+ bone marrow cells either from Bcl6+/+, Bcl6−/− or Bcl6BTBMUT mice (50%) into sub-lethally irradiated Rag1−/− mice, which are congenitally deficient in mature B and T cells (Fig. 3a). All CD45.2+ donor cells showed a similar developmental pattern in T and B lineages prior to the GC stage (date not shown). As expected, GC B and TFH cells derived from CD45.2+ Bcl6−/− donor cells were effectively absent after SRBC immunization as compared to wild-type CD45.1+ cells in the mixed chimeras (Fig. 3b,c). By contrast, whereas CD45.2 donor Bcl6BTBMUT cells exhibited profound deficiency in formation of GC B cells, they formed normal numbers of TFH cells (Fig. 3b,c). The reduction of TFH cells observed in the homozygous Bcl6BTBMUT knockin setting is thus secondary to the lack of GC B cells.

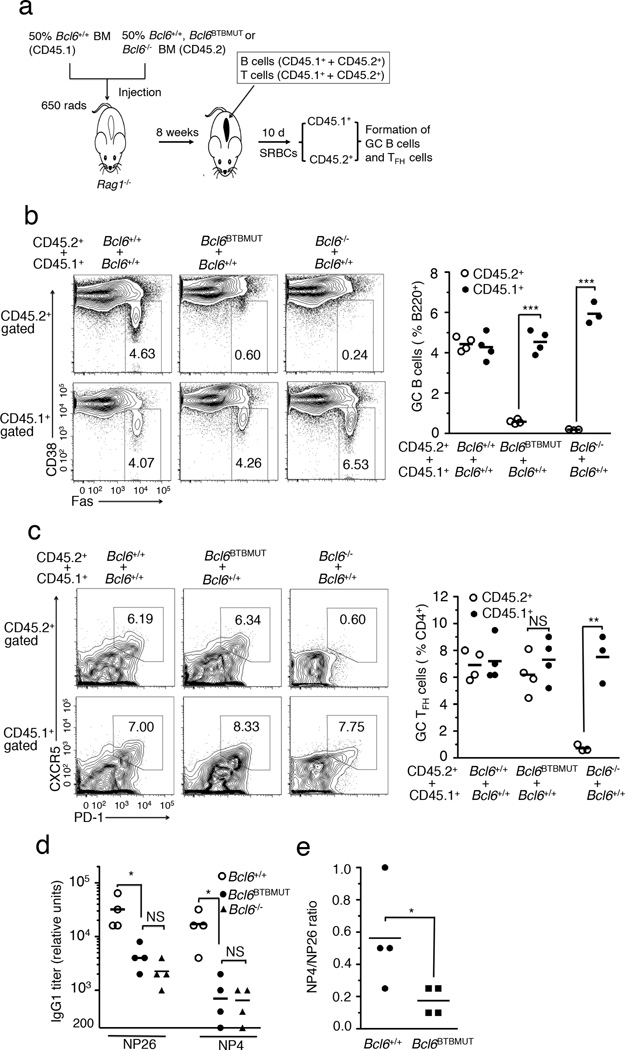

Figure 3. Bcl6BTBMUT mice show impaired GC response in B cell-autonomous manner.

(a) The strategy for generation of chimera using mixed bone marrow transplantation. (b) The frequency of GC B cells (FAS+ CD38low/−, boxed) among live B220+ cells in CD45.1 and CD45.2 donors was quantified by flow cytometry (left) and plotted (right) in chimeras 7 d after immunization with SRBCs. (c) The frequency of GC TFH cells (CXCR5hiPDhi, boxed) among live B220−CD4+ T cells in CD45.1 and CD45.2 donors was quantified by flow cytometry (left) and plotted (right). Numbers in outlined areas indicate percent GC B cells (b) and percent GC TFH cells (c). (d,e) Sera were collected from µMT mixed mice 21 d after immunization with NP-CGG, described in Supplementary Fig. 5a. Titers of IgG1 measured with NP26-BSA and NP4-BSA (d). Ratio of the titers of IgG1 detected with NP4-BSA to those with NP26-BSA (e). Each symbol represents an individual mouse and small horizontal lines indicate means (b–e). Data are from three independent experiments with four mice per genotype. NS, not significant; *P<0.05; **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 (two-tailed t test, b,c and one-tailed t test, d,e).

To determine whether impaired immunoglobulin affinity maturation in Bcl6BTBMUT mice is also intrinsic to B cells we reconstructed chimeras by transferring µMT bone marrow (50%) along with bone marrow cells (50%) from either Bcl6+/+, Bcl6BTBMUT or Bcl6−/− mice into sub-lethally irradiated Rag1−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 5a). µMT bone marrow cells provide a source of normal T cells but no B cells, thus all B cells in these chimeras originate from tested donor bone marrow cells. Bcl6BTBMUT mixed chimeras formed few GC B cells and GCs after SRBC immunization, quite similar to Bcl6−/− mixed chimeras (Supplementary Fig. 5b–d). The titers of NP-specific IgG1 antibodies in Bcl6BTBMUT mixed chimeras were reduced to 16% and 6% of those in Bcl6+/+ mixed chimeras after NP-CGG immunization when NP26-BSA and NP4-BSA were used as capture antigen, respectively (Fig. 3d). The ratio of titers detected with NP4-BSA to those with NP26-BSA was significantly lower in Bcl6BTBMUT than Bcl6+/+ mixed chimeras (Fig. 3e). These results demonstrate B cell-intrinsic requirement of BTB-mediated repression for immunoglobulin affinity maturation and development of functional GC B cells.

Bcl6BTBMUT GC B cells manifest reduced proliferation and survival

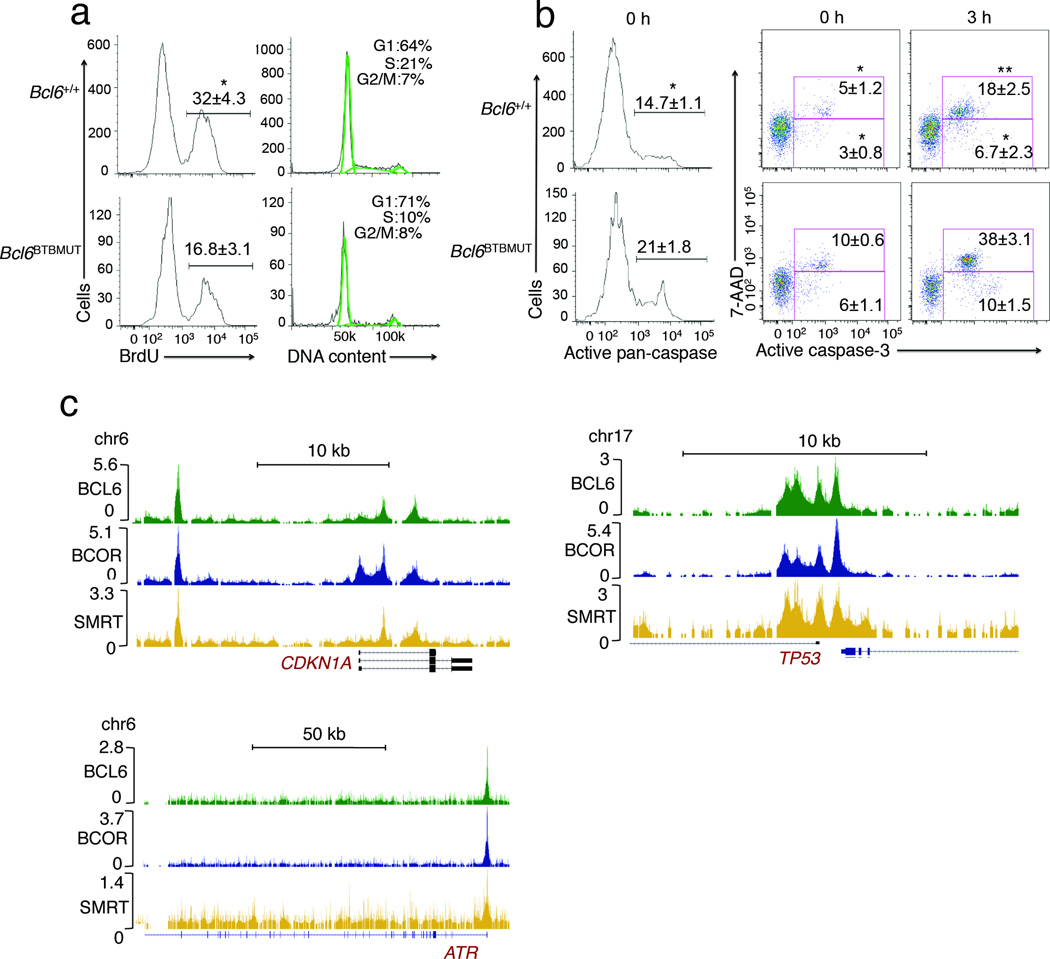

Bcl-6 suppresses checkpoints controlling cell proliferation and survival, which may explain how GC B cells proliferate so rapidly and tolerate somatic hypermutation6, 7, 9, 10. We reasoned that inability to enact this proliferative and pro-survival phenotype might explain the failure of Bcl6BTBMUT mice to form functional GCs. The rate of cell proliferation in vivo was determined by BrdU incorporation. Less than 1% of non-GC B cells incorporated BrdU in either wild-type or Bcl6BTBMUT mice (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Notably, while 32±4.3% of GC B cells in Bcl6+/+ mice incorporated BrdU, only 16.8±3.1%; of GC B cells were BrdU-positive in Bcl6BTBMUT animals (Fig. 4a). Cell cycle analysis displayed an increased fraction of GC B cells arrested in the G1 phase with corresponding reduction in S-phase in Bcl6BTBMUT mice (Fig. 4a). We next assessed the abundance of apoptotic cells by evaluating active caspase and 7-AAD staining. Whereas 14.7±1.1% of GC B cells in Bcl6+/+ mice were positive for pan-caspase activation, this fraction was increased to 21±1.75% in Bcl6BTBMUT animals (Fig. 4b). Bcl6BTBMUT GC B cells also exhibited more cells with active caspase-3 (7-AAD−, 6±1.1% vs 3±0.8% and 7-AAD+, 10±0.6% vs 5±1.2%) as compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 4b). Notably, after 3 h incubation, Bcl6BTBMUT GC B cells still exhibited a greater proportion of active caspase-3+7-AAD− cells (10±1.5% vs 6.7±2.3%) and active caspase-3+7-AAD+ cells (38±3.1% vs 18±2.5%) as compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 4b). As expected, less than 4% of freshly isolated or ex vivo cultured non-GC B cells were caspase-3+7-AAD+/− in either wild-type or Bcl6BTBMUT (Supplementary Fig. 6b). These data indicate that the Bcl-6 BTB lateral groove is required to facilitate rapid proliferation and survival in GC B cells. Along these lines we examined the binding profiles of Bcl-6, BCOR and SMRT in primary human GC B cells using ChIP-seq and observed that both corepressors were present together with Bcl-6 at the promoters of key checkpoint target genes including ATR, TP53 and CDKN1A (Fig. 4c). The presence of these complexes is consistent with data showing that expression of these genes are induced by exposure to peptides that block the BTB lateral groove6, 28, 32.

Figure 4. The Bcl-6 BTB lateral groove is required for GC B cell proliferation and survival.

(a,b) Bcl6BTBMUT or Bcl6−/− mice were immunized with SRBCs and the resulting GC B cells examined by flow cytometry for (a) BrdU incorporation (left) and DNA content (right). (b) Active caspae-3 or pan-caspase positive cells were assessed by incubation with FITC-DEVD-FMK or FITC-VAD-FMK respectively and flow cytometry. Dead cells were identified as 7-AAD positive. These assays were performed in fresh isolated (left and middle panels) or ex vivo cultured splenocytes. All plots were gated on splenic FAS+CD38lo-negB220+ GC B cells. Data are from two independent experiments with three to four mice per genotype and shown as means±SD. *P<0.05; **P<0.01 (two-tailed t test). (c) ChIP-seq signals of Bcl-6, SMRT and BCOR in human tonsil germinal center B cells at the ATR, TP53 and CDKN1A gene loci. Data are representative of three independent experiments..

Bcl6BTBMUT TFH cells support GC immunoglobulin affinity maturation

Results shown above indicate that the Bcl-6 BTB domain is dispensable for formation of TFH cells (Fig. 3c). To define whether Bcl6BTBMUT TFH cells are competent to support GC functions including immunoglobulin affinity maturation, chimeras were generated by transferring Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− bone marrow cells (80%) along with tested bone marrow cells (20%) from either Bcl6+/+, Bcl6BTBMUT or Bcl6−/− animals into sub-lethally irradiated Rag1−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− bone marrow cells provide a source of normal B cells but no T cells, thus chimeric mice would only be able to form functional GCs if the tested bone marrow provides a source of normal TFH cells. Bcl6BTBMUT, but not Bcl6−/− mixed chimeras formed equal abundance of GC B cells and normal GCs in spleens as Bcl6+/+ mixed chimeras after SRBC immunization (Fig.5a,b and Supplementary Fig. 7b). Moreover, titers of NP-specific IgG1 antibodies in NP-CGG immunized Bcl6BTBMUT mixed chimeras were indistinguishable to those in Bcl6+/+ mixed chimeras when either NP26-BSA or NP4-BSA were used as capture antigen (Fig.5c). The ratio of titers detected with NP4-BSA to those of NP26-BSA was also similar to wild-type (Fig. 5d). Hence Bcl6BTBMUT mice form fully functionally competent TFH cells.

Figure 5. Normal germinal center response in Bcl6BTBMUT, Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− mixed chimeras.

Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− mixed chimeras were generated as described in Supplementary Fig. 6a. (a,b) Representative flow cytometric contour plots of GC B cells (FAS+ CD38lo-neg, boxed) gated on live splenic B220+ lymphocytes (a) and PNA staining of spleen sections (b) from chimeras 10 d after immunization with SRBCs. Numbers in the outlined box indicate the percentages (a). (c,d) Sera were collected from chimeras 21 d after immunization with NP-CGG. Titers of IgG1 were measured with NP26-BSA and NP4-BSA (c). Ratio of the titers of IgG1 and IgG2a were detected with NP4-BSA to those with NP26-BSA (d). Each symbol represents an individual mouse and small horizontal lines indicate means. Data are representative of three independent experiments with three mice (a,b) and from two independent experiments with four mice (c,d). NS, not significant; *P<0.05 (one-tailed t test, c,d).

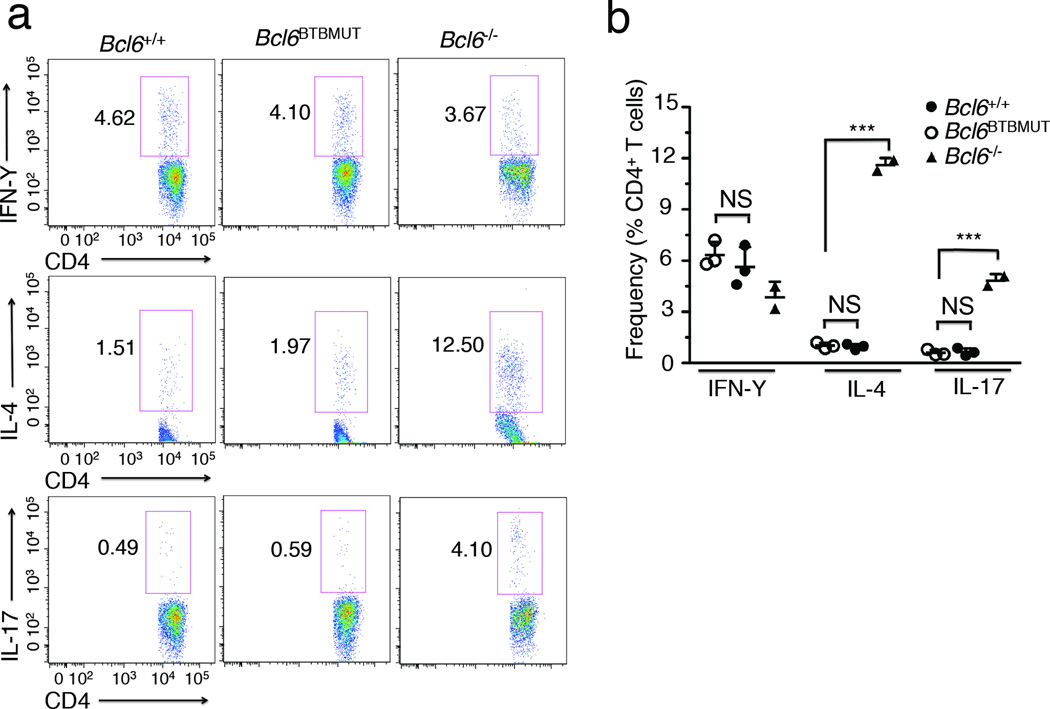

Bcl6BTBMUT mice display normal TH2 and TH17 differentiation

Bcl6−/− mice universally exhibit T cell skewing towards the TH2 and TH17 lineage, which contribute to aberrant inflammatory signaling and the eventual death of these animals3, 4, 33. This defect can be triggered and aggravated by immunization34. To better define the contribution of the BTB domain lateral groove to the differentiation of these effector T helper subtypes, we isolated splenocytes from age-matched Bcl6BTBMUT mice and wild-type littermates, and measured the relative abundance of TH1, TH2 and TH17 cells. At baseline Bcl6BTBMUT mice have similar numbers of TH1, TH2 and TH17 cells to wild-type littermates (data not shown). We next analyzed T helper cell subtypes in mice immunized with SRBCs. As previously reported, Bcl6−/− mice exhibited a significant increase in the number of TH2 (11.5 ±0.4% versus 1±0.2%) and TH17 cells (4.8 ±0.4% versus 0.6±0.2%) as compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 6a,b). In contrast, Bcl6BTBMUT mice displayed similar numbers of TH2 (0.98 ±0.3% versus 1±0.2%) and TH17 cells (0.62 ±0.3% versus 0.6±0.2%) to wild-type mice (Fig. 6a,b). Thus the BTB lateral groove is not involved in Bcl-6-mediated suppression of TH2 and TH17 differentiation in vivo.

Figure 6. Bcl6BTBMUT mice display normal TH2 and TH17 differentiation.

(a) Flow cytometric analysis of chemokine production by splenic CD4+ T cells stimulated with PMA (20 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1 µg/ml) in the presence of Golgi-Plug (1 µg/ml) for 5 h before staining for CD4, IL-4, IFN- IL-17. Numbers adjacent to the outlined box indicate the percentages. (b) Quantification of TH1, TH2 and TH17 cells as percentage of CD4+ T cells based on flow cytometry as in a. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Data are representative of two independent experiments (means ±SD of two to three mice). NS, not significant; ***P<0.001 (two-tailed t test).

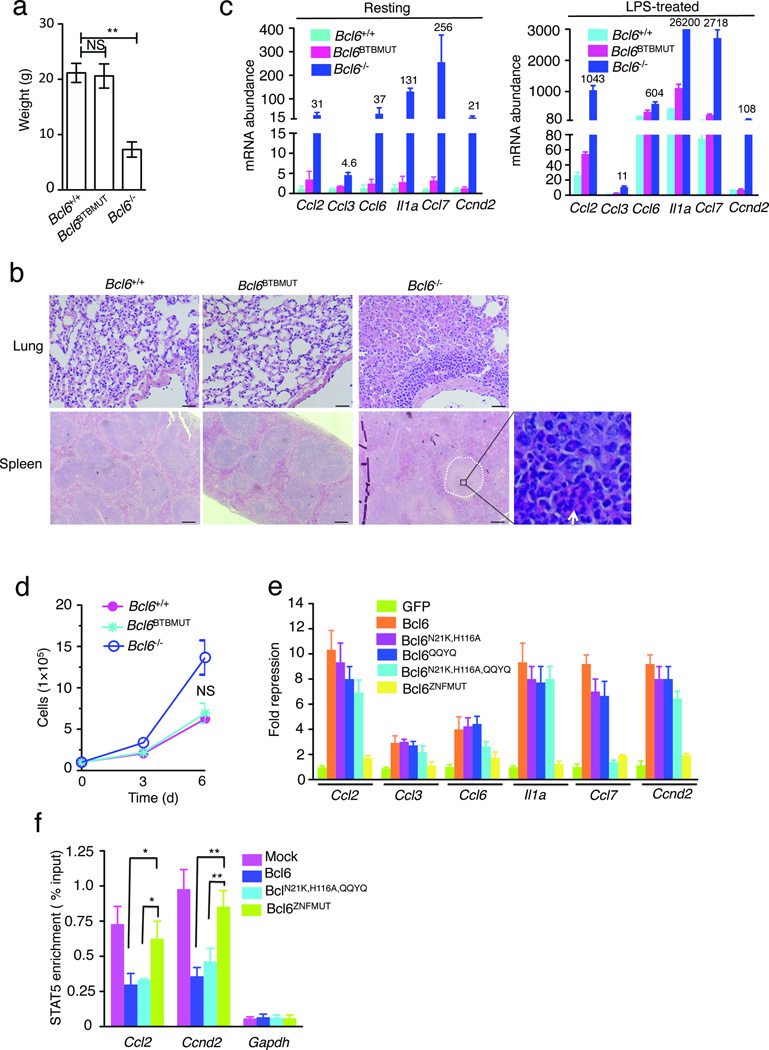

Bcl6BTBMUT mice lack the Bcl6−/− inflammatory phenotype

Bcl6−/− mice are born at lower than expected frequencies, are runted and develop a severe TH2-type inflammatory syndrome involving multiple organs frequently including lung and spleen3, 4. However, we observed that Bcl6BTBMUT are born at expected Mendelian frequencies, are developmentally indistinguishable from wild-type littermates and have normal body weights (Fig. 7a). By six weeks more than half of Bcl6−/− mice had died whereas all Bcl6BTBMUT mice remained healthy even after one year of monitoring. Bcl6−/− mice displayed the expected inflammatory cell infiltrate in lung and multinodular lesions characterized by the infiltration of eosinophils in spleen, whereas histological studies of organs including lungs, spleen, heart, liver, thymus, kidney, and intestine displayed no such infiltrates in Bcl6BTBMUT mice (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Fig. 8a). The phenotype was confirmed in two independent founder lines with different genetic backgrounds (data not shown).

Figure 7. Bcl6BTBMUT mice fail to develop TH2-type inflammation disease and display nearly normal inflammation-related gene expression in macrophages.

(a) Body weight of indicated mice at eight-weeks old (n=6). (b) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung and spleen sections from indicated mice. Scale bars, 200 µm. Multinodular lesion in Bcl6−/− spleen is marked by white cycle and the infiltration by eosinophils is indicated by arrow in inset (original magnification, ×40). (c) mRNA expression of indicated genes in resting (left) or LPS (5 µg/ml)-treated bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) cultured from indicated mice (n=3). Data were from three independent experiments and represent as fold-upregulation relative to wild-type resting after normalization with Hprt. Numbers adjacent to blue bars indicate fold in each. (d) Growth curve of BMDMs cultured from indicated mice. (e) mRNA expression of indicated genes in sorted GFP+ population from Bcl6−/− BMDMs infected with a bicistronic retrovirus containing internal ribosomal entry site GFP expressing indicated Bcl-6 forms. Results are shown as fold repression compared to GFP after normalization with Hprt. (f) STAT5 binding at indicated genomic loci in puromycin-resistant Bcl6−/− BMDMs infected with indicated retrovirus. The fold enrichment was calculated as percentage of input. Data represent at least three independent experiments (means ±SD in a, d–f). NS, not significant; *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 (two-tailed t test).

Minimal effect on chemokine expression in Bcl6BTBMUT macrophages

Inflammatory chemokines such as CCL2, CCL3, CCL6, CCL7 and IL-1a are highly up-regulated in Bcl6−/− macrophages and believed to be critical mediators of the lethal inflammatory response in Bcl6−/− animals18, 19. Bcl-6 also suppresses macrophage proliferation through repression of CCND235, a critical cell cycle driver. The surprising lack of inflammatory phenotype in Bcl6BTBMUT mice prompted us to measure chemokine expression and proliferation of macrophages isolated from these animals. We first measured the mRNA abundance of inflammatory response genes (Ccl2, Ccl3, Ccl6, Il1a, Ccl7 and Ccnd2) by qPCR in resting and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated macrophages from wild-type, Bcl6BTBMUT and Bcl6−/− mice. Most of these genes were up-regulated more than 20-fold in Bcl6−/− resting macrophages versus wild-type controls, and were further induced by LPS treatment (Fig. 7c). In contrast, Bcl6BTBMUT macrophages showed no more than 1.4- to 4-fold increase of basal expression of these genes when compared to wild-type cells, and this limited upregulation was not further enhanced by LPS treatment (Fig. 7c). As expected, Bcl6−/− macrophages divided faster, whereas Bcl6BTBMUT macrophages showed very similar proliferation rate to wild-type macrophages (Fig. 7d).

To determine whether other Bcl6 domains more significantly contribute to repression of inflammatory genes, Bcl6−/− macrophages were transduced with retrovirus expressing either wild-type Bcl-6, Bcl-6BN21K,H116A point mutations same as in the Bcl6BTBMUT mice, Bcl-6 with mutations inactivating the RD2 repression domain (Bcl-6QQYQ)36, or double mutant Bcl-6 (Bcl-6N21K,H116A,QQYQ). All of these mutants retained the ability to suppress chemokine and inflammatory gene expression (Fig. 7e). By contrast expression of Bcl-6 harboring mutation in its third C2H2 zinc finger (Bcl-6ZNFMUT) that abolishes DNA binding without affecting nuclear localization nuclear localization37 was completely unable to repress these target genes (Fig. 7e). Hence, while DNA binding is required for repression of chemokines, the BTB lateral groove is dispensable for this function, consistent with the lack of inflammatory phenotype in Bcl6BTBMUT mice.

Bcl-6 ChIP-seq performed in macrophages has shown that Bcl-6 binding sites are highly enriched in STAT motifs including those in the chemokine genes tested here19. Bcl-6 was proposed to potentially compete with STATs for binding to certain target genes30, 31, 38. Loss of Bcl-6 DNA binding might thus enhance the recruitment of STAT proteins to these inflammation-related gene loci. Here we used STAT5 as an example. Wild-type and Bcl6−/− primary murine macrophages present similar abundance of active STAT535. By performing qChIP assays we observed reciprocal changes in STAT5 and Bcl-6 binding at the promoters of Ccl2 and Ccnd2 gene in wild-type vs. Bcl6−/− primary murine macrophages, with significantly enhanced enrichment of STAT5 in the absence of Bcl-6 (Supplementary Fig. 8b,c). Most remarkably, expression of wild-type Bcl-6 as well as Bcl-6N21K,H116A,QQYQ, but not Bcl-6ZNFMUT in Bcl6−/− primary murine macrophages impaired STAT5 enrichment at both of these chemokine loci (Fig. 7f).

DISCUSSION

Considering that Bcl-6 and its BTB domain corepressors are expressed together in most Bcl-6-expressing tissues, the biochemical function of Bcl-6 would be expected to be similar among cell types, and its tissue-specific function perhaps mediated by binding to distinct sets of target genes. Indeed, genomic localization studies of Bcl-6 in different cell types suggested that its transcriptional targets are partially cell type specific19, 28, 29. Yet evidence for a more profound, biochemical level of functional diversification was hinted by studies employing cell-penetrating peptides designed to dissociate the Bcl-6 BTB domain and its corepressors39, 40. Administration of the peptide to mice bearing human lymphoma xenografts induced growth arrest and apoptosis in lymphoma cells but did not induce the Bcl6−/− inflammatory phenotype39, 40. Unfortunately the peptide studies are limited in their interpretation due to the unknown kinetics and level of inhibition of Bcl-6 in various cell types, as well as relatively time-limited exposure. Introducing point mutations within the native Bcl6 locus in mice thus affords constitutive loss of BTB domain repressor function in all tissues while preserving proper timing and level of expression, allowing us to gain the critical insights into the function of this unique biochemical mechanism of Bcl-6.

Bcl6BTBMUT animals displayed a normal early extrafollicular response, but impaired late germinal center response after T cell dependent immunization. Importantly, loss of BTB domain repression function manifested as failure of GC B cells to proliferate and survive, even in the presence of wild-type TFH cells and microenvironment. Hence the function of the Bcl-6 BTB domain is specifically, to enable the proliferative and DNA damage tolerant phenotype of GC B cells, possibly through repressing ATR, TP53, CDKN1A. Blockade of the BTB domain with peptide inhibitors in primary GC B cells and DLBCL cells results in derepression of these genes6, 32. One implication of these results is the notion that the same biochemical function through which Bcl-6 specifically mediates the GC B cell phenotype also drives the survival and proliferation of DLBCL cells. Targeting the Bcl-6 BTB domain with peptide or small molecule inhibitors kills DLBCL cell lines in vitro and in vivo, as well as primary human DLBCL cells ex vivo39–41. Hence DLBCLs are essentially driven by a normal transcriptional mechanism derived from their cell of origin.

Similar to Bcl6−/− mice, Bcl6BTBMUT animals displayed few GC TFH cells and reduced CXCR5+PD1+ TFH cells. However in marked contrast to T cell development in Bcl6−/− mice, Bcl6BTBMUT animals generated perfectly functional TFH cells after immunization in the presence of normal cognate B cells. Since cognate B cells are absolutely required for differentiation and maintenance of GC TFH cells42–44, the defect in GC-TFH cells in Bcl6BTBMUT animals is likely secondary to the defect in the B cell compartment. The fact that the deficit in CXCR5+PD1+ TFH cells is less pronounced is likely related to the preservation of the early, extrafollicular phase of the immune response that we observed in Bcl6BTBMUT mice. Altogether the mechanisms underlying the deficiency of TFH phenotype in Bcl6BTBMUT and Bcl6−/− animals are completely different. Further research is thus needed to explain the biochemical mechanism through which Bcl-6 mediates the TFH cell phenotype. Perhaps different sets of corepressors binding to different sites on the Bcl-6 protein are involved.

Another salient finding from phenotypic analysis of Bcl6BTBMUT mice was the absence of the lethal Bcl6−/− inflammatory disease, implying that the BTB domain lateral groove is dispensable for Bcl-6 functions in the innate immune system. In macrophages Bcl-6 attenuates inflammatory responses through repression of chemokines and NF-κB target genes18, 19, 35. Enhanced inflammatory signaling in Bcl6−/− macrophages also deregulates T cell development, resulting in skewing towards TH2 and TH17 differentiation33, eventually forming a vicious circle leading to destructive infiltration by T cells of various tissues. Loss of Bcl6 was also recently reported to confer a striking atherogenic and xanthomatous tendinitis phenotype45, reminiscent of human familial hypercholesterolemia. None of these phenotypes were observed in Bcl6BTBMUT animals. As compared to Bcl6−/− macrophages, inflammatory cytokine expression was at best partially deregulated and proliferation was normal in Bcl6BTBMUT macrophages. It was the Bcl-6 DNA binding domain and not the BTB domain that was most critical to repress chemokine expression in Bcl6−/− macrophages. The explanation for this finding may relate to how transcriptional repressors and activators can compete for promoter occupation by mutually exclusive binding to overlapping DNA elements46. Indeed Bcl-6 and STATs bind to overlapping consensus binding sites19, 25, 28, 29. Results presented herein reveal reciprocal binding of Bcl-6 and STAT5 to key macrophage inflammatory genes. Hence, passive DNA binding competition of Bcl-6 with STATs may be a dominant biochemical function of Bcl-6 in innate immunity rather than its interaction with corepressors.

Finally, this study has important implications for the clinical translation of Bcl-6 inhibitors designed to disrupt corepressor binding to the BTB domain39, 40, which are currently being translated for use in patients with Bcl-6-dependent tumors. The potential for such drugs to cause systemic inflammation and atherosclerosis is a potential concern for humans treated with these compounds. Our data show that such side effects would be unlikely to occur, consistent with reported toxicity studies of these inhibitors in animals39. In summary, by constructing a genetically engineered knockin that constitutively disrupts corepressor binding to the BTB domain we were able for the first time to demonstrate that Bcl6 mediates immunological lineage-specific effects through different protein interactions thus providing a new paradigm for transcription factor functional diversification.

METHODS

Generation of Bcl6BTBMUT knockin mice

The mutations encoding N21K and H116A amino acid substitutions were introduced into exon 3 and exon 4 of Bcl6 BAC (ID: RP24-371N16, the Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Center) using a GalK positive/counterselection strategy. A neor cassette flanked by two loxP sites was inserted into Bcl6 intron 3 800-bp upstream to the H116 residue. Finally, 2.0-kb DTA cassette replaced the 1.0-kb genomic fragment that is 2.0-kb downstream to the 3' loxP site (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The targeting vectors were linearized and electroporated into 129×C57BL/6 mixed ES cells. Two clones confirmed to contain the homologous-targeted mutation were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts and these blastocytes were implanted in pseudopregnant female mice. Germ-line transmission resulted in the generation of Bcl6BTBMUT/+ mice containing neor cassette in knockin allele. These mice were mated to C57BL/6 TgE2a-Cre mice (Jackson Laboratory) to remove the floxed neor cassette, generating Bcl6BTBMUT/+ knockin mice. These mice were further bred to C57BL/6 mice for at least five generations and intercrossed to obtain homozygotes for most experiments. To study the development of inflammation diseases in Bcl6BTBMUT mice, Bcl6BTBMUT/+ knockin mice were bred to Sv129 mice (Jackson Laboratory) for three generations and intercrossed to obtain homozygotes.

Mice and mixed bone marrow chimera studies

Bcl6−/− mice were kindly provided by H. Ye (Albert Einstein Medical College). To generate mixed bone marrow chimera, 4×106 bone marrow cells from a mixture of B6.SJL (CD45.1, Jackson Laboratory) and Bcl6+/+ or Bcl6−/− or Bcl6BTBMUT with a ratio 1:1, or of µMT (Jackson laboratory) and Bcl6+/+ or Bcl6−/− or Bcl6BTBMUT with a ratio 1:1, or of Tcrb−/−Tcrd−/− (Jackson laboratory) and Bcl6+/+ or Bcl6−/− or Bcl6BTBMUT with a ratio 4:1 were intravenously transferred into sub-lethally irradiated Rag1−/− mice (Jackson Laboratory). Eight weeks later, the recipient mice were immunized and sacrificed for further analysis of germinal center formation and antibody production. Mice were housed in the SPF animal facility at Weill Cornell Medical College and the animal experiments were performed using protocols approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Intracellular Cytokine staining

For flow cytometric analysis of cytokine-secreting, spleen cells were stimulated with PMA (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, 20 ng/ml, Invitrogen) and inomycin (1µg/ml, Invitrogen) in the presence of Golgi-Plug (1 µg/ml, Invitrogen) for 5 h and stained with antibodies against the indicated cell surface markers, followed by permeabilization in Fix/Perm buffer, and intracellular staining in Perm/Wash buffer (BD Pharmingen).

BrdU detection, cell cycle and apoptosis assays

For BrdU labeling, mice were intravenously administrated with 2 mg BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) 2 h before being killed. Splenocytes were prepared and stained appropriate cell surface markers. Then BrdU-positive cells were detected by BrdU Flow kits (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For cell cycle analysis, splenocytes were stained with appropriate cell surface makers and fixed in fixation/permeable buffer (FoxP3 staining set, eBioscience) for 45 min, followed by DAPI staining. The phase distribution was analyzed automatically using Dean-Jett-Fox model (Flowjo). For detection of apoptosis in situ, fresh isolated or 3-hour incubated splenocytes were maintained for 1 h at 37 °C with FITC-VAD-FMK or FITC-DEVD-FMK (BioVision) in RPMI medium. Cells were washed according to the manufacturer's protocol and then were labeled with the appropriate antibodies for surface phenotyping.

ChIP-qPCR

Cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde and neutralized with 0.125 M glycine. Cell lysates were sonicated to 300–500 bp and immunoprecipitations were performed with anti-Bcl6 (N3, Santa Cruz), anti-SMRT (Millipore), anti-STAT5 (sc-835, Santa Cruz) or IgG as controls. After complete washing, immunoprecipitated DNA was eluted in elution buffer and reversely cross-linked at 65°C overnight. DNA was purified and quantified by real-time PCR (primer sequences, Supplementary Table 1). The enrichment fold was calculated to percentage of input.

Immunization, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay

For analysis of the formation of germinal center, mice were immunized intraperitoneally with SRBC (108 cells per mouse) or NP21-CGG (Biosearch Technologies) in imject Alum (Pierce) for indicated days. For analysis of T cell-independent antibody production, mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 100 µg NP26-Ficoll (Biosearch Technologies) and analyzed for 8 days. For analysis of T cell-dependent antibody production, mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 100 µg NP21-CGG. On days 8 and 21 post-immunization, sera was collected and titers of isotype-specific antibodies to nitrophenol (NP) were measured in plates coated with BSA-NP26 or BSA-NP4 using SBA Clonotyping System (Southern Biotech) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Titers were presented as the greatest serum dilution that provided an average absorbance exceeding 1.5-fold above the average background absorbance at 405 nm. For ELISPOT assay, spleen cells were incubated for 20 h at 37 °C on NP26-BSA-coated 96-well MultiScreen-HA filter plates (Millipore). Spots were visualized with goat anti-mouse IgG or IgM antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Southern Biotechnology) and color was visualized by addition of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Southern Biotechnology).

Immunoblot analysis

B220+ cells were isolated from indicated spleens using mouse B220 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and analyzed by immunoblot for measurement of protein expression. Anti-Bcl6 (D8) and anti-actin (C-11) were from Santa Cruz.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared with TriZol regent (Invitrogen) or the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). cDNA were synthesized using Superscript reverse transcriptase and random primer (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was performed using Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) to examine the mRNA level of genes. (primer sequences, Supplementary Table 2).

BMDM culture, retrovirus production and transduction

BMDM were cultured as published by Toney et. al.18. After 8 days culture, mature macrophages were scraped off the dish, washed with PBS and re-plated in complete DMEM. The cells adhered overnight and then fresh media was added with or without 5 µg/ml LPS (LPS E. coli 055:B5; Sigma-Aldrich) for 6 h before collected. Expression constructs for wild-type Bcl6 and Bcl6N21K,H116A has been described24. Expression constructs for Bcl6QQYQ, Bcl6N21K,H116A and Bcl6ZNFMUT were generated using QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits (Agilent Technologies). cDNA fragmented encoding wild-type and various mutant Bcl6 were sub-cloned into MIGR1-GFP or MIGR1-puromycin retroviral expression vector. Viral supernatants were prepared using Plat-E cells according to the standard protocol. For retrovirus infection, bone marrow cells were maintained in complete DMEM for 4 days and infected with viral supernatants in the presence of 8 µg/ml polybrene (Sigma). For MIGR1-GFP infected cells, GFP+ cells were sorted to determine gene expression by quantitative RT-PCR seven days post-infection. For MIGR1-puromycin infected cells, puromycin-resistant cells were selected by adding 2 µg/ml puromycin (Invitrogen) and used for QChIP assays.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test was performed for statistical analysis. The software GraphPad Prism 5 was used for this analysis. P-value more than 0.05 is considered to be no significance.

Other methods including immunochemistry, antibodies and flow cytometric analysis are described in Supplementary information.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AM is supported by NCI R01 104348. AM is also supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Foundation and Chemotherapy Foundation. This research was initially supported by a March of Dimes Basil O’Connor Scholar Award (AM). This work was facilitated by the Sackler Center for Biomedical and Physical Sciences at Weill Cornell Medical College. We thank H. Ye from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine for sharing Bcl6−/− mice and W. Pear for providing MIGR1 expression vector. We thank D. Wen and S. Rafii from Weill Cornell Medical College for assistance in generating Bcl6BTBMUT knockin mice.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.H. designed and executed most of the reported experiments. K.H. performed and analyzed ChIP-seq experiment. A.M. conceived the project and wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declared no competing financial interests.

ACCESSION CODES

GEO: ChIP-seq data, GSE43350

REFERENCES

- 1.Ye BH, et al. Alterations of a zinc finger-encoding gene, BCL-6, in diffuse large-cell lymphoma. Science. 1993;262:747–750. doi: 10.1126/science.8235596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cattoretti G, et al. BCL-6 protein is expressed in germinal-center B cells. Blood. 1995;86:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dent AL, Shaffer AL, Yu X, Allman D, Staudt LM. Control of inflammation, cytokine expression, and germinal center formation by BCL-6. Science. 1997;276:589–592. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ye BH, et al. The BCL-6 proto-oncogene controls germinal-centre formation and Th2-type inflammation. Nat Genet. 1997;16:161–170. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukuda T, et al. Disruption of the Bcl6 gene results in an impaired germinal center formation. J Exp Med. 1997;186:439–448. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.3.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranuncolo SM, et al. Bcl-6 mediates the germinal center B cell phenotype and lymphomagenesis through transcriptional repression of the DNA-damage sensor ATR. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:705–714. doi: 10.1038/ni1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ranuncolo SM, Polo JM, Melnick A. BCL6 represses CHEK1 and suppresses DNA damage pathways in normal and malignant B-cells. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2008;41:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerchietti LC, et al. BCL6 repression of EP300 in human diffuse large B cell lymphoma cells provides a basis for rational combinatorial therapy. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4569–4582. doi: 10.1172/JCI42869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phan RT, Dalla-Favera R. The BCL6 proto-oncogene suppresses p53 expression in germinal-centre B cells. Nature. 2004;432:635–639. doi: 10.1038/nature03147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phan RT, Saito M, Basso K, Niu H, Dalla-Favera R. BCL6 interacts with the transcription factor Miz-1 to suppress the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 and cell cycle arrest in germinal center B cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1054–1060. doi: 10.1038/ni1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crotty S. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH) Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Pelletier N, Mark L, Fazilleau N, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Follicular helper T cells as cognate regulators of B cell immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu D, et al. The transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 directs T follicular helper cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2009;31:457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nurieva RI, et al. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science. 2009;325:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.1176676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston RJ, et al. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science. 2009;325:1006–1010. doi: 10.1126/science.1175870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroenke MA, et al. Bcl6 and Maf cooperate to instruct human follicular helper CD4 T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2012;188:3734–3744. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crotty S, Johnston RJ, Schoenberger SP. Effectors and memories: Bcl-6 and Blimp-1 in T and B lymphocyte differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:114–120. doi: 10.1038/ni.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toney LM, et al. BCL-6 regulates chemokine gene transcription in macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:214–220. doi: 10.1038/79749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barish GD, et al. Bcl-6 and NF-kappaB cistromes mediate opposing regulation of the innate immune response. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2760–2765. doi: 10.1101/gad.1998010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhordain P, et al. Corepressor SMRT binds the BTB/POZ repressing domain of the LAZ3/BCL6 oncoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:10762–10767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huynh KD, Bardwell VJ. The BCL-6 POZ domain and other POZ domains interact with the co-repressors N-CoR and SMRT. Oncogene. 1998;17:2473–2484. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huynh KD, Fischle W, Verdin E, Bardwell VJ. BCoR, a novel corepressor involved in BCL-6 repression. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1810–1823. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmad KF, et al. Mechanism of SMRT corepressor recruitment by the BCL6 BTB domain. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1551–1564. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00454-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghetu AF, et al. Structure of a BCOR corepressor peptide in complex with the BCL6 BTB domain dimer. Mol Cell. 2008;29:384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang CC, Ye BH, Chaganti RS, Dalla-Favera R. BCL-6, a POZ/zinc-finger protein, is a sequence-specific transcriptional repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6947–6952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujita N, et al. MTA3 and the Mi-2/NuRD complex regulate cell fate during B lymphocyte differentiation. Cell. 2004;119:75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendez LM, et al. CtBP is an essential corepressor for BCL6 autoregulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2175–2186. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01400-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ci W, et al. The BCL6 transcriptional program features repression of multiple oncogenes in primary B cells and is deregulated in DLBCL. Blood. 2009;113:5536–5548. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-193037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basso K, et al. Integrated biochemical and computational approach identifies BCL6 direct target genes controlling multiple pathways in normal germinal center B cells. Blood. 2010;115:975–984. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-227017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reljic R, Wagner SD, Peakman LJ, Fearon DT. Suppression of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3-dependent B lymphocyte terminal differentiation by BCL-6. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1841–1848. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris MB, et al. Transcriptional repression of Stat6-dependent interleukin-4-induced genes by BCL-6: specific regulation of iepsilon transcription and immunoglobulin E switching. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7264–7275. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cerchietti LC, et al. Sequential transcription factor targeting for diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3361–3369. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mondal A, Sawant D, Dent AL. Transcriptional repressor BCL6 controls Th17 responses by controlling gene expression in both T cells and macrophages. J Immunol. 2010;184:4123–4132. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dent AL, Hu-Li J, Paul WE, Staudt LM. T helper type 2 inflammatory disease in the absence of interleukin 4 and transcription factor STAT6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13823–13828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu RY, et al. BCL-6 negatively regulates macrophage proliferation by suppressing autocrine IL-6 production. Blood. 2005;105:1777–1784. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bereshchenko OR, Gu W, Dalla-Favera R. Acetylation inactivates the transcriptional repressor BCL6. Nat Genet. 2002;32:606–613. doi: 10.1038/ng1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mascle X, Albagli O, Lemercier C. Point mutations in BCL6 DNA-binding domain reveal distinct roles for the six zinc fingers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:391–396. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02873-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernandez de Mattos S, et al. FoxO3a and BCR-ABL regulate cyclin D2 transcription through a STAT5/BCL6-dependent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10058–10071. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.10058-10071.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cerchietti LC, et al. A peptomimetic inhibitor of BCL6 with potent antilymphoma effects in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2009;113:3397–3405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polo JM, et al. Specific peptide interference reveals BCL6 transcriptional and oncogenic mechanisms in B-cell lymphoma cells. Nat Med. 2004;10:1329–1335. doi: 10.1038/nm1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cerchietti LC, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of BCL6 kills DLBCL cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:400–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kerfoot SM, et al. Germinal center B cell and T follicular helper cell development initiates in the interfollicular zone. Immunity. 2011;34:947–960. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goteri G, et al. Comparison of germinal center markers CD10, BCL6 and human germinal center-associated lymphoma (HGAL) in follicular lymphomas. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:97. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-6-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi YS, et al. ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity. 2011;34:932–946. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barish GD, et al. The Bcl6-SMRT/NCoR cistrome represses inflammation to attenuate atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2012;15:554–562. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hermsen R, Tans S, ten Wolde PR. Transcriptional regulation by competing transcription factor modules. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.