Abstract

Objective

This longitudinal study examined how observations of parental general communication style and control with their adolescents predicted changes in negative affect over time for adolescent smokers and non-smokers.

Method

Participants were 9th and 10th grade adolescents (N = 111; 56.8% female) who had all experimented with cigarettes and were thus at risk for continued smoking and escalation; 36% of these adolescents (n = 40) had smoked in the past month at baseline and were considered smokers in the present analyses. Adolescents participated separately with mothers and fathers in observed parent-adolescent problem-solving discussions to assess parenting at baseline. Adolescent negative affect was assessed at baseline, 6- and 24-months via ecological momentary assessment.

Results

Among both smoking and non-smoking adolescents, escalating negative affect significantly increased risk for future smoking. Higher quality maternal and paternal communication predicted a decline in negative affect over 1.5 years for adolescent smokers but was not related to negative affect for non-smokers. Controlling maternal, but not paternal, parenting predicted escalation in negative affect for all adolescents.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that reducing negative affect among experimenting youth can reduce risk for smoking escalation. Therefore, family-based prevention efforts for adolescent smoking escalation might consider parental general communication style and control as intervention targets. However, adolescent smoking status and parent gender may moderate these effects.

Keywords: Parent-Child Interactions, Adolescents, Negative Affect, Smoking

Negative affect (NA) and smoking are strongly linked in adolescence (see Kassel, Stroud, & Paronis, 2003, for a review). Adolescents who report higher levels of depressed mood or NA are more likely to initiate smoking and escalate to regular smoking levels (e.g., Kim, Fleming, & Catalano, 2009; Windle & Windle, 2001). Smoking adolescents are also at risk for worsening depressive symptoms (e.g., Chaiton, Cohen, O'Loughlin, & Rehm, 2009; Windle & Windle, 2001). Parenting may play a role in this complex phenomenon via its effects on both youth smoking trajectories (e.g., Gutman, Eccles, Peck, & Malanchuk, 2011) as well as depressed mood (see McLeod, Weisz, & Wood, 2007 and Sheeber, Hops, & Davis, 2001, for reviews) and broader NA constructs (Connor & Rueter, 2006; Steinberg, 2001). Compared to other social and emotional predictors, evidence implicating parental influences on adolescent smoking tends to be weak; yet, some assert that largely unexplored mechanisms might explain the overall modest effect (Darling & Cumsille, 2003). For example, parenting may influence smoking, particularly among experimenting youth, by increasing exposure to smoke-triggering events, such as stressors (e.g., directly and indirectly via involvement with deviant peer groups; Darling & Cumsille, 2003). NA may also be one such “trigger” or at the very least, closely related to them. Given the link between parenting and NA, and the bidirectional nature of NA and smoking, identifying parenting factors leading to better NA outcomes in youth at high-risk for smoking escalation might have preventative implications for smoking behavior.

This study employed direct observation of parent-adolescent interactions and ecological momentary assessment (EMA; Shiffman, Stone, & Hufford, 2008) to examine how parental interactional qualities, general communication style and control, differentially predicted long-term mood outcomes for current adolescent smokers and non-smokers. We define negative affect broadly here, considering a variety of NA constructs including sadness, stress, and anger. This nuanced methodology may better explicate this parent-adolescent phenomenon and yield theoretical and family-based clinical implications for youth at high-risk for smoking escalation.

Parenting and Smoking: Theories Implicating the Role of Negative Affect

The family environment, particularly the quality of parent-child interactions, has been a widely established source of protection, or risk, in pathways of adolescent substance use. One prominent theory used to explain these parental effects is the stress-coping model (e.g., Wills, 1985; Wills & Filer, 1996). Specifically, scholars suggest that providing youth with a supportive parental environment will enhance their ability to cope with stressors and negative emotional states. Wills and Cleary (1996) provided empirical evidence for this model by showing that supportive parental interactions reduced adolescent substance use (composite of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana) directly and indirectly, by enhancing coping skills (among other factors).

Considerable evidence exists to support the notion that youth smoke as maladaptive way of coping with NA. Although bi-directional models of NA and smoking have been well-established using multiple indices of both smoking and mood, Chaiton et al. (2009) use self-medication theory (Khantzian, 1997) to emphasize that depressive symptoms leading to smoking is the more likely path due to adolescents’ tendencies to use cigarettes to ameliorate negative mood states. It is important to note that the between-subjects NA-smoking link does not automatically provide evidence for self-medication (Kassel et al., 2003). However, previous analyses using EMA data from the current study indicated that at the within-person level, adolescent smokers report experiencing improved moods (i.e. lower NA) after smoking compared to their own non-smoking, random, times (Hedeker, Mermelstein, Berbaum, & Campbell, 2009). We thus have ecologically valid support for probable affect improvement motivations even among light adolescent smokers.

Previous research has emphasized that smoking persistence from experimental levels is particularly affected by environmental influences, including difficult interactions with parents (Lewinsohn, Brown, Seeley, & Ramsey, 2000). Yet, as asserted by Darling and Cumsille (2003), stable family characteristics may predict change in smoking behavior but cannot necessarily be deemed the proximal cause of this change. Accordingly, examining the impact of parenting on adolescent smoking requires attention to its effects on more proximal and perhaps similarly dynamic factors, such as NA, that may be more intimately tied to cigarette use (e.g., Hedeker et al. 2009; Kassel et al., 2003). Together, the stress-coping and self-medication theories of adolescent substance use strongly suggest that identifying factors to improve NA outcomes among adolescents experimenting with smoking, perhaps by improving the quality of their parental interactions, might lessen the degree to which they turn to cigarettes as means to cope with stress and negative mood states.

Parenting and Negative Affect

To our knowledge, no one has yet investigated how dimensions of parenting within observed parent-adolescent interactions predict real-time, long-term mood outcomes in youth at high risk for smoking. The literature linking parenting to adolescent global depressed mood has identified that dimensions of parental rejection (i.e., low support and high hostility) and parental control (i.e., interference with autonomy) are most consistently associated with depressive outcomes (McLeod et al., 2007). Parental support and control dimensions have also been independently linked to adolescent smoking (e.g., Darling & Cumsille; Gutman et al., 2011), and previous research has documented the importance of evaluating them together to prospectively predict adolescent substance use behavior (Stice, Barrera, & Chassin, 1993). In the current study, we developed and examined two parental interactional dimensions: general communication style and control. General communication style is defined as the quality of responsiveness, clarity, and positivity of behavior and statements within the interaction; its components are thus related to the rejection construct described but more closely evaluate the content of communication as well as the behavior. Control is defined as the level and quality of power and autonomy-inhibition within the interaction. Although this study considered real-time reports of NA and not global depressive symptoms, these factors are moderately correlated (Weinstein, Mermelstein, Hankin, Hedeker, & Flay, 2007), and similar links between parenting and mood may be found with NA.

Direct observations of parent-adolescent interactions have established a link between the quality of parenting and adolescents’ depressive symptoms (Sheeber, Davis, Leve, Hops, & Tildesley, 2007; Sheeber, Hops, Alpert, Davis, & Andrews, 1997) as well as general emotional distress (Connor & Rueter, 2006). A study by Sheeber and colleagues (1997) showed that negative maternal communication (i.e., statements and behavior conveying low support and high conflict) during parent-adolescent problem-solving interactions predicted higher levels of adolescent depressive symptoms cross-sectionally and prospectively, over one year. Sheeber et al. (2007) later found that depressed and subclinically depressed adolescents experienced more aversive interactions (i.e., low support and high conflict) with both parents than non-depressed youth. These findings highlight the association between the quality of observed communication in problem-solving interactions and adolescent mood, as well as emphasize the need to examine both paternal and maternal influences.

Extensive parenting research emphasizes that parents can support their adolescent children by promoting their autonomy and facilitating their enhanced desire for behavioral and emotional independence (Steinberg, 2001). In fact, studies show that parental control is related to worse psychosocial outcomes, particularly depressive symptoms in adolescents (e.g., McLeod et al., 2007). Kakihara and Tilton-Weaver (2009) recently used hypothetical vignettes of parent-child interactions to examine how adolescents perceive varying levels of parental control over personal domains (e.g., friendship choices and substance use). They found that high levels of either behavioral or psychological parental control were perceived by adolescents as similarly negative and intrusive. Researchers suggested that such interpretations of parental control may in turn, lead to emotional maladjustment.

Parent-adolescent interactional qualities may have differential effects depending upon the behavioral risk-status of youth. For example, recent research has shown that adolescents with varying risk profiles may be uniquely emotionally reactive to their family environment (Schneiders et al., 2006; 2007). Schneiders et al. (2007) examined the influence of immediate social contexts on momentary mood responses in high- and low-risk youth. Researchers defined “high risk” as adolescents with emotional and behavioral risk factors for poor mental health outcomes, including higher levels of smoking. Results from their study showed that high-risk adolescents reported greater depressed mood when with their families compared to low-risk adolescents but no differences in other social contexts. A separate analysis with this same sample (Schneiders et al., 2006) found that high- and low-risk adolescents did not differ in the total daily negative events experienced; however, high-risk youth reported more negative events involving family and peers. Across social contexts, high-risk adolescents reported higher levels of depressed mood in response to negative events compared to low-risk youth. Researchers posited that exposure to aversive parent-child interactions might be one mechanism whereby high-risk adolescents develop depressed moods (Schneiders et al., 2007). Any smoking in adolescence tends to be associated with mood and behavioral problems, and these problems may be increasingly prevalent in youth who progress to higher smoking levels (Kim et al., 2009; Lewinsohn et al., 2000). Thus, this research suggests that smoking risk status alone may moderate the effect of environmental experiences and lends support to the utility of examining how parent interactional qualities influence NA in smoking and non-smoking adolescents.

Benefits of Real-time Data Collection

Electronic diary methods, such as EMA, have gained appeal as sensitive and effective ways of obtaining real-time reports of affective states (Shiffman et al., 2008). EMA provides numerous methodological benefits to global reporting, in that it is sensitive enough to detect both individual variation and between-person differences, and it avoids many of the reporting biases existing in global measures (Shiffman et al., 2008). Our understanding of how parenting influences adolescent adjustment has also been heavily guided by global questionnaires (e.g., Sheeber et al., 2001). As a result, knowledge of this relationship relies largely on adolescents’ perceptions of the family environment and is also influenced by shared method variance. Direct observations of parent-child interactions allow researchers to examine real processes of behavior and explore mechanisms of influence (Aspland & Gardner, 2003). As such, behavioral observation strategies allow insight into specific targets for interventions (Sheeber et al., 2001).

The Present Study

The present study examined how maternal and paternal general communication style and control with their adolescents predicted changes in real-time NA over 1.5 years for adolescent smokers and non-smokers. It is important to strongly emphasize that youth defined as smokers in the present study had not only tried smoking in the past, but also continued to smoke at the baseline measurement wave, rendering them an especially high-risk group for smoking escalation. This study enhances existing literature in multiple ways. First, it assessed both interaction quality and adolescent affect “in the moment”, via direct observational assessment and real-time reports of adolescent mood. Second, we extended recent work showing the distinct emotional reactivity of high- and low-risk youth (e.g., Schneiders et al., 2006; 2007), by examining how parenting differentially influenced real-time, long-term mood in smokers and non-smokers. Finally, we examined these effects for both mothers and fathers, thus expanding the literature regarding paternal influences on adolescent outcomes.

Given the established association between higher observed parental communication quality and lower depressive symptoms (e.g., Sheeber et al., 2007), we predicted a main effect of general communication, such that higher quality general communication would be protective for all adolescents and associated with a decline in NA. Furthermore, based on reports of the perceived negative nature of parental control, and the unique reactivity of higher-risk youth, we hypothesized a main effect of parental control and an interaction between parental control and adolescent smoking status on NA. Specifically, we predicted that higher parental control would be associated with escalations in NA for all adolescents; however, this association would be significantly stronger in smokers compared to non-smokers. In addition, we predicted that these effects would be similar across mothers and fathers.

Methods

Overview of Design, Participant Recruitment, and Description

Data for this study come from the baseline, 6-, and 24- month assessment waves of a large longitudinal study investigating the social and emotional contexts of adolescent smoking patterns. The cornerstone of the longitudinal study was the establishment of a cohort of adolescents comprised primarily of youth who had ever smoked. Participants were recruited from 16 Chicago-area high schools. The sample was derived in a multi-stage process. All 9th and 10th graders at the schools (N = 12,970) completed a brief screening survey of smoking behavior. Invitations were mailed to eligible students and their parents. Students were eligible to participate in the longitudinal study if they fell into one of four levels of smoking experience: 1) never smokers; 2) former experimenters (smoked at least one cigarette in the past year, have not smoked in the last 90 days, and have smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime); 3) current experimenters (smoked in the past 90 days, but smoked less than 100 cigarettes in lifetime); and 4) regular smokers (smoked in the past 30 days and have smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime).

We mailed recruitment packets to 3,654 eligible students and their parents. These recruitment targets included all youth in the “current experimenter” and “regular smoker” categories plus random samples from the “never smoker” and “former experimenter” categories. Youth were enrolled into the longitudinal study after written parental consent and student assent was obtained. All youth and parents had to agree to potentially participate in all components of the larger, program project study including multiple, longitudinal questionnaire assessments, EMA, a family observation study (Family Talk), a psychophysiological laboratory assessment study, and parent questionnaires. Of the 3,654 students invited to participate in the overall project, 1,344 agreed to participate (36.8%). Of these, 1,263 (94.0%) completed the baseline measurement wave. Agreement to participate did not vary by smoking history, race/ethnicity, or parental smoking, but females were slightly more likely to agree to participate than males.

The sample for the current study (N = 111) consisted of 9th and 10th graders who completed the baseline self-report questionnaire, Family Talk, and the baseline, 6-, and 24-month EMA assessments. All had smoked at least once in the past year at baseline and were recruited from the “former experimenter” and “current experimenter” categories developed during initial recruitment. Mean age of the participants at baseline was 15.57 (SD = 0.60); 56.8% were females, and the racial/ethnic composition was as follows: 55.0% White, 25.2% Black, 13.5% Hispanic, 0.9% Asian or Pacific Islander, and 5.4% Other. Parental education for the sample was as follows: 24.3% completed high school or less, 22.5% completed some college, and 41.4% completed college or more; 11.7% was unknown. To evaluate attrition effects, we compared those included in the present sample to thirteen youth who completed the baseline and 6-month assessments but did not have 24-month follow-up data. These thirteen participants were more likely to be smokers at baseline (n = 9; 69.2%), χ2(1, N = 124) = 5.37, p =.021 (Cramer's V = .21), but no differences were observed on other relevant variables. Female caregivers, “mothers” (n = 104) were 95.2% birth mothers, 4.8% step-mothers, aunts, grandmothers, or other female relative. Their mean age was 43.46 (SD = 6.57), and 24.0% (n =25) were current smokers. Participating “fathers” (n = 70) were 91.4% birth fathers, 8.6% step-fathers, uncles, and adoptive fathers. Their mean age was 46.85 (SD = 6.92), and 20.0% (n = 14) were current smokers.

Procedures

Three methods of data collection were used for the current investigation: 1) parent and adolescent self-report questionnaires at baseline 2) EMA at baseline, 6, and 24 months, and 3) Family Talk parent-adolescent observational paradigm that took place between the baseline and 6-month collection waves. Procedures during all phases of the study received approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Questionnaire Measures

Self-report questionnaire packets were mailed to adolescents two weeks prior to each data wave, and the participant was instructed to bring the completed packet to his/her EMA training session. Parents were mailed self-report questionnaires after the adolescents’ baseline visits were completed. A sub-set of parents completed questionnaires on the day of the Family Talk visit.

Demographic information

Demographic information was assessed via questionnaire and included age, gender, race/ethnicity, and parents’ education level.

Adolescent Smoking Status

Current smoking was assessed at baseline and 24 months by asking participants to “Think about the past 30 days. On how many days did you smoke cigarettes?” Based on the standard definitions of current smoking among adolescents (e.g., Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2009), we recoded this outcome into a dichotomous variable. We created one group of non-smokers (n = 71; 64.0%), those who reported not smoking in the past 30 days at baseline, and one group of smokers (n = 40; 36.0%). To emphasize the high-risk nature of our sample, 2006 data (the same year our baseline data was collected) from the Monitoring the Future Study (Johnston et al., 2009), found that only 14.5% of the nationally representative sample of 10th graders reported smoking in the past 30 days. On average, smokers in our sample reported smoking cigarettes on 3.70 days in the past month at baseline (Range: 1-25). At 24 months, there were also 71 non-smokers and 40 smokers; however, 18 adolescents who were baseline non-smokers became 24-month smokers, and 18 adolescents who were baseline smokers were not smoking at 24 months. On average, smokers at 24 months reported smoking cigarettes on 10.96 days in the past month (Range: 1-30).

Parent Smoking Status

Parent smoking status was assessed via parent questionnaire at baseline by asking the parent to report on their own smoking history. Current smokers were those who reported currently smoking cigarettes on a daily basis. All others were considered non-smokers. Missing data from parent questionnaires were completed using adolescents’ reports of their parents’ smoking behavior.

Ecological Momentary Assessment

All participants received training on the use of the EMA device at the beginning of the data collection week and carried the device for seven consecutive days at each wave. The device randomly prompted the adolescents throughout the day to answer questions about their mood, behavior, and situation; only mood items were analyzed in the current study. Each EMA interview asked participants to rate their mood “just before the signal”. Adolescents responded to several mood adjectives using a 10-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 10 (very). The current study examined one sub-scale developed from factor analysis conducted on a larger sample of all youth participating in the EMA (n = 461): NA (angry, frustrated, irritable, sad, stressed; Chronbach's alpha ranged from .94 to .96 across waves). To obtain NA outcome variables for the current analyses, we averaged each participant's NA scale reports from all random prompts (approximately 30) throughout each data-collection week separately at baseline, 6, and 24 months. For the preliminary analysis, the NA change score was calculated by subtracting the mean NA at baseline from the mean at 24 months. The NA change score for the primary analyses was calculated by subtracting the mean NA at 6 months from the mean NA at 24 months (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Mood and Parenting Variables for the Total Sample and by Baseline Adolescent Smoking Status

| Total | Baseline Smokers | Baseline Non-smokers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | Cohen's d | |

| Negative Affect | ||||||||||

| Baseline NA | 111 | 3.30 | 1.44 | 40 | 3.81 | 1.60 | 71 | 3.02 | 1.27 | 0.57** |

| 6 Month NA | 111 | 3.19 | 1.53 | 40 | 3.75 | 1.67 | 71 | 2.87 | 1.35 | 0.60** |

| 24 Month NA | 111 | 3.27 | 1.47 | 40 | 3.66 | 1.64 | 71 | 3.05 | 1.33 | 0.42* |

| Change Baseline → 24 Months | 111 | -0.03 | 1.45 | 40 | -0.15 | 1.68 | 71 | 0.04 | 1.32 | 0.13 |

| Change 6 Months → 24 Months | 111 | 0.08 | 1.36 | 40 | -0.09 | 1.61 | 71 | 0.18 | 1.21 | 0.20 |

| Mother | ||||||||||

| Communication Style | 104 | 5.76 | 1.31 | 37 | 6.14 | 1.09 | 67 | 5.55 | 1.38 | 0.46* |

| Control | 104 | 5.13 | 0.94 | 37 | 5.08 | 0.85 | 67 | 5.16 | 1.00 | 0.08 |

| Father | ||||||||||

| Communication Style | 70 | 5.17 | 1.36 | 29 | 5.33 | 1.40 | 41 | 5.07 | 1.33 | 0.19 |

| Control | 70 | 4.88 | 1.17 | 29 | 4.79 | 1.00 | 41 | 4.95 | 1.28 | 0.14 |

Note. For comparison of adolescent smokers and non-smokers.

Significant difference between smokers and non-smokers, p < .05

Significant difference between smokers and non-smokers, p < .01.

NA = Negative Affect.

For Cohen's d, the absolute value is shown.

Family Talk

Observational paradigm

The majority of observational data were collected in families’ homes, with a small number collected at the University laboratory (n = 4) or a private room in a school or public library (n = 12). To minimize participant reactivity, field staff monitored the videotaping via a monitor in an adjacent room. When two parents participated, order of administration was randomly determined by a coin toss. Family observations consisted of one “cool” and two “hot” topics (Hops, Tildesley, Lichtenstein, Ary, & Sherman, 1990), each lasting about 10 minutes. This study focused on the set of two problem-solving segments (5 minutes each), in which first teen and then parent raised a topic on which they disagreed and tried to resolve it (Wakschlag, Chase-Lansdale, & Brooks-Gunn, 1996). Behaviors coded across segments were based on the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scale (IFIRS; Melby & Conger, 2001). All observed behaviors were adapted to match the IFIRS 9-point rating scale, which provides 5 defined anchors (i.e., 1 = not at all characteristic, 3 = minimally characteristic, 5 = somewhat characteristic, 7 = moderately characteristic, 9 = mainly characteristic) and 4 unanchored midpoints. Ratings are based on intensity, frequency, proportion and quality of observed verbal and non-verbal behavior. The IFIRS has been used extensively to assess interactions of ethnically diverse samples of parents and adolescents. Intraclass correlations for single rating scales have been reported to range from .55 to .85 (Melby & Conger, 2001). Previous studies have showed good utility for the IFIRS regarding explorations of how parenting within family interactions may be related to adolescent outcomes, including behavior problems (Scaramella & Conger, 2003) as well as emotional distress and suicidality (Connor & Rueter, 2006). See Wakschlag et al. (2011) for more information on reliability procedures.

Based on standards reported by Cicchetti et al. (2006), adequate interrater reliability was demonstrated for all rated IFIRS codes used in the present study (M ICC = .64, range = .40–.82). Parenting dimensions in the present study were derived from exploratory factor analysis using varimax rotations on all individual IFIRS parenting codes. This analysis was conducted on all parents with problem-solving segment data in the larger family talk project (n = 533). Two factors developed from these analyses were explored in the present study: general communication style and control. For the present study, IFIRS codes were first averaged across the two problem-solving segments (i.e., parent and teen-raised problems). The combination problem-solving code was then averaged with the other codes in each parenting domain to create the final communication style and control composite scores for each parent (general communication style codes (n = 3): assertiveness, communication, and listener responsiveness; control codes (n = 5): dominance, encourages independence, interrogate, lecture/moralize, and parental influence).

Parent observational ratings

General Communication Style (coefficient alpha = .83)

General communication style assesses the quality of responsiveness, clarity, and positivity of communication and behavior in the interaction. Higher quality communication can be described as positive in affect and tone, responsive, directive, and empathic. Lower quality communication can be described as negative in affect and tone, unresponsive, coercive, and critical. Assertiveness measures the degree to which the parent demonstrates confidence in verbal or nonverbal expression through clear, appropriate and neutral or positive expression, and shows patience with the child. The communication code measures the extent to which the parent conveys his/her opinions, rules, or general information in a neutral or positive manner. Listener responsiveness measures the extent to which the parent attends to and validates the child's responses.

Control (coefficient alpha = .73)

Control measures the extent to which the parent interacts with his/her child in a commanding and autonomy-limiting manner. Examples of high control might include an overly-involved parent who makes overt attempts to lead the child and the interaction. More specifically, the dominance code measures the degree to which the parent attempts and is successful in controlling or influencing the child and/or situation. Encourages independence assesses the extent to which the parent promotes the adolescent's autonomy and independence in both thought and action (this was reverse-coded). Interrogate measures the degree to which the parent asks questions with the goal of obtaining specific information or making a point rather than communicating genuine interest in the child's thoughts or feelings. Lecture/Moralize measures the level at which the parent speaks to the child in an intrusive, pushy, and/or “lectury” manner. Parental influence measures the degree to which the parent attempts to socialize the child by setting standards and regulates the child's behavior within the interaction and through inference, within daily life.

Independent samples t-tests revealed that mothers displayed higher quality communication compared to fathers, t(172) = 2.87, p =.005 (Cohen's d =.44). Mothers and fathers did not significantly differ in observed control, t(172) = 1.54, p =.126 (Cohen's d = .24).

Results

Preliminary Analysis – Smoking and Negative Affect

As a preliminary step, we evaluated the clinical utility of examining how changes in real-time reports of NA predicted smoking over time. Specifically, we conducted a binary logistic regression analysis to assess how changes in NA from baseline to 24 months predicted 24-month smoking status, controlling for baseline NA and baseline smoking rate (days smoked/month). For this analysis, we examined the change in NA from baseline to 24 months (as opposed to from 6 to 24 months) to partial out the concurrent covariance between NA and smoking status. Based on previous research linking escalations in depressive symptoms to smoking behavior (e.g., Windle & Windle, 2001), we predicted similar findings using this real-time measure of NA. As expected, results revealed that the change in NA from baseline to 24 months was associated with significantly increased odds of being a smoker at 24 months (see Table 2). A separate analysis examined whether baseline smoking status moderated the main effect of the change in NA on 24-month smoking; this effect was not significant and will not be discussed further.

Table 2.

Results of Logistic Regression Predicting 24-Month Smoking Status, N = 111

| b | SE | p-value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||

| Days smoked | 0.34 | 0.15 | .025 | 1.40 | 1.04 | 1.89 |

| Mean Baseline NA | 0.13 | 0.17 | .436 | 1.14 | 0.82 | 1.59 |

| Change in NA (baseline to 24 Months) | 0.36 | 0.17 | .031 | 1.44 | 1.03 | 2.00 |

Note. Model χ2= 17.31, df = 3, p = .001. Smoking outcome coded as 0 = no and 1 = yes. NA = Negative affect; CI = Confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

Parenting and Negative Affect

Analytic Approach

We conducted standard moderated regression analyses, separately for mothers and fathers. Centered scores representing parental communication and control, and their interaction with adolescent smoking status, were used to predict the change in NA from 6 to 24 months, controlling for mean NA at 6 months and adolescent gender. All significant interactions were probed and plotted using techniques outlined by Holmbeck (2002).

Parent Smoking and Outcomes

We first considered parent smoking status (current or not current) in regressions, but its inclusion did not substantially change the results and thus removed from further analyses. We also examined whether parental smoking status moderated the interaction between parenting dimensions and adolescent smoking on NA. None of these three-way interactions were statistically significant and will not be discussed further. We also examined whether parent smoking status influenced adolescent smoking, NA, and observed parenting behavior. Maternal smoking status was not significantly associated with any of these outcomes. Paternal smoking status was only associated with the change in adolescent NA from 6 to 24 months. Independent samples t-tests revealed that children of smoking fathers demonstrated significantly more escalation in NA over time (M = 0.83, SD = 1.20) compared to children of non-smoking fathers (M = -0.04, SD = 1.15), t (68) = -2.53, p = .014 (Cohen's d = .75).

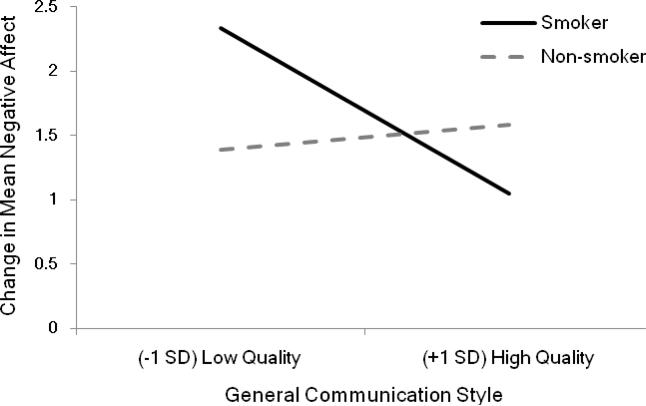

Mothers

Contrary to hypotheses, there was no main effect of maternal communication style on the change in NA. However, there was a significant interaction between maternal communication style and adolescent smoking on NA (see Table 3). Specifically, follow-up analyses revealed that among smokers, higher quality maternal communication was associated with a decline in NA, b = -0.49, t (96) = -2.31, p = .023. Among non-smokers, there was no association between communication style and a change in NA, b = 0.07, t (96) = 0.66, p = .511 (see Figure 1). As expected, controlling parenting was associated with escalation in NA. Yet, diverging from predictions, there was no interaction between maternal control and youth smoking status on NA. That is, the strength of this effect was not significantly different for smokers and non-smokers.

Table 3.

Parental Standard Regressions Predicting Change in Negative Affect over Time

| b | SE | t | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers (n =104) | ||||

| Gendera | -0.02 | 0.23 | -0.10 | .923 |

| Mean NA 6 Monthsb | -0.44 | 0.08 | -5.42 | < .001 |

| Baseline Smoking Statusc | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.78 | .436 |

| Communication Style | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.66 | .511 |

| Controlling Parenting | 0.35 | 0.15 | 2.32 | .023 |

| Communication Style × Smoking Status | -0.57 | 0.24 | -2.33 | .022 |

| Controlling Parenting × Smoking Status | -0.42 | 0.31 | -1.34 | .184 |

| Fathers (n = 70) | ||||

| Gendera | -0.03 | 0.27 | -0.09 | .927 |

| Mean NA 6 Monthsb | -0.34 | 0.10 | -3.49 | .001 |

| Baseline Smoking Statusc | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.96 | .341 |

| Communication Style | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.70 | .484 |

| Controlling Parenting | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.56 | .578 |

| Communication Style × Smoking Status | -0.50 | 0.21 | -2.46 | .017 |

| Controlling Parenting × Smoking Status | -0.06 | 0.26 | -0.22 | .824 |

Note. Model for mothers: F(7, 96) = 6.77, p <.001. Model for fathers: F(7, 62) = 2.85, p =.012.

Gender coded as 0 = female 1 = male.

NA = Negative affect.

Smoking coded as 0 = no and 1 = yes.

Figure 1.

Simple slopes of the quality of maternal communication style on the change in negative affect from 6 to 24 months as a function of adolescent smoking status.

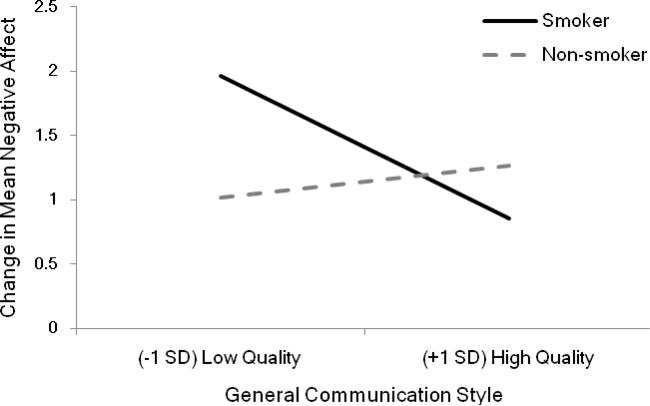

Fathers

Consonant with results found for mothers, and differing from predictions, there was no main effect of paternal communication style on the change in NA. Rather, results revealed a significant interaction between general communication style and adolescent smoking on NA (see Table 3). Follow-up analyses showed that higher quality communication was associated with a decline in NA for smokers, b = -0.41, t (62) = -2.62, p = .011, but was not related to a change in NA for non-smokers, b = 0.09, t (62) = 0.70, p = .484 (see Figure 2). Contrary to hypotheses, results did not reveal an association between controlling paternal parenting and NA, or a controlling parenting by smoking status interaction.

Figure 2.

Simple slopes of the quality of paternal communication style on the change in negative affect from 6 to 24 months as a function of adolescent smoking status.

We also conducted analyses only among adolescents who participated with both a mother and father (n = 59; 53.15%), so that results could be more easily compared across parents. Results were generally similar among this smaller sample.

Discussion

This longitudinal, multimethod study prospectively examined the differential effects of parental interactional qualities, assessed by direct observation, on changes in NA over time, assessed via EMA, for current adolescent smokers and non-smokers. All youth had previously experimented with smoking, and thus the smokers defined in the present study represent a particularly high-risk group for smoking escalation. Results revealed that higher quality maternal and paternal general communication style each predicted a decline in NA for smokers but was not associated with NA for non-smokers. Maternal controlling parenting predicted escalation in NA for all adolescents. Findings extend the literature in a few specific ways. First, this study examined parental interactional qualities and adolescent affect “in the moment”, thus circumventing many reporting biases of retrospective reports and providing a multi-method assessment of these associations. Second, we extended the cross-sectional findings identifying the unique emotional reactivity of higher-risk youth (Schneiders et al., 2006; 2007), by examining a similar, albeit a smoking-specific effect, longitudinally. Finally, our examination of both mothers and fathers enhances the burgeoning research on fathers and emphasizes their importance to adolescent emotional adjustment.

Smoking and Negative Affect

Preliminary results revealed that escalation in NA from baseline to 24 months predicted significantly increased odds of being a smoker at 24 months for all adolescents. This effect was found even after controlling for baseline smoking rate, consistently shown to be the strongest predictor of future smoking behavior (e.g., Windle & Windle, 2001). This finding is somewhat limited by the dichotomous coding of smoking. Nonetheless, it adds evidence to extant research linking increases in NA and depressive symptoms to smoking behavior (e.g., Kassel et al., 2003), by showing that escalations in real time reports of NA over two years also increase risk for future smoking in adolescence. This finding lends support to the clinical utility of identifying factors predicting better affective outcomes among youth at high-risk for smoking escalation.

Parenting and Adolescent Negative Affect

General Communication Style

Results revealed that higher quality maternal and paternal communication were both associated with a decline in NA for smokers but were not associated with NA in non-smokers. As expected, findings for communication style were similar across both mothers and fathers. These results are notable given how underrepresented fathers are in the parent-adolescent literature (e.g., Sheeber et al., 2001). The paternal effects on long-term mood outcomes corroborate previous observational research linking the observed quality of paternal communication with adolescent emotional adjustment (e.g., Connor & Rueter, 2006; Sheeber et al., 2007), and extend these findings using a real-time assessment of adolescent affect.

The significant interaction between parental communication and adolescent smoking was contrary to our predictions. Yet, a closer evaluation of the communication style construct may help elucidate this differential influence. That is, low quality communication encompasses lack of engagement as well as hostility and coerciveness. Due to the correlational nature of these results, findings could also be interpreted to mean that low quality communication was associated with escalation in NA for smokers but not non-smokers. Based on this bi-dimensional framework, results may corroborate with existing research by Schneiders et al. (2006) showing that high-risk adolescents experienced greater depressed mood in response to negative events. These findings suggest that smokers may experience more negative emotional responses to difficult parental interactions, which may impact long-term mood.

In addition, adolescent smoking occurs in conjunction with numerous other negative circumstances. For example, even minimal adolescent smoking is associated with psychosocial impairments (Lewinsohn et al., 2000), and many of these problems are particularly robust among youth who escalate (e.g., Kim et al., 2009). Adolescent smoking is also often associated with increased affiliation with smoking and generally deviant peer groups (see Simons-Morton & Farhat, 2010, for a review), which alone have been shown to cross-sectionally and prospectively predict increased depressive symptoms in adolescents (Richmond, Mermelstein, & Metzger, 2012). Despite previous contentions that all adolescents experience maladaptive patterns of affect throughout adolescence, persistent mood disturbances tend only to occur among adolescents facing problems in multiple life domains (Arnett, 1999). Perhaps maintaining positive parent-child communication reduces the overall number of negative events faced by smoking youth, reduces their stress, and improves long-term emotional outcomes.

Results might also be explained by social learning mechanisms for teaching effective coping skills, often implicated in family processes involved in adolescent depression (Sheeber et al., 2001) and stress-coping models of substance use (Wills & Cleary, 1996). That is, parents who communicate in a positive, responsive and empathic manner, especially in a problem-solving discussion, are modeling and facilitating the development of both effective skills for coping with difficult interactions and regulating negative emotion. Research has established that avoidant coping strategies for handling stressful situations, proven to be higher in late adolescents (age 18) who escalate in smoking (Bricker, Schiff, & Comstock, 2011), have been shown to prospectively predict higher levels of depressive symptoms in adolescents (Seiffge-Krenke & Klessinger, 2000). Based in and extending upon earlier evidence for the role of parenting in stress-coping models (Wills & Cleary, 1996), we suggest that positive parental communication may improve long-term NA outcomes for smokers by teaching more adaptive coping techniques already used by non-smokers.

Controlling Parenting

In contrast with communication style, maternal, but not paternal, parental control was associated with increases in NA for all adolescents. The main effect of maternal control on NA was consistent with hypotheses; however, the similar effect across both smokers and non-smokers diverged from our predictions. Despite the fact that our smokers represent a higher-risk group in terms of smoking-specific behavior, the sample as whole was enriched for past smoking behavior. It is possible then that the overall high-risk nature of our sample regarding risk behavior might lead to parental control being viewed as similarly intrusive and negative. Despite the fact that previous research has shown that higher levels of parental control may be protective against certain types of substance use (e.g., alcohol; Stice et al., 1993), this suggests that controlling parenting might be employed more cautiously among youth already engaging in problematic behaviors. Based on the link between NA and future smoking found in the whole sample (not just among baseline smokers), parental control appears to be an appropriate target of escalation prevention for youth at varying levels of cigarette experimentation.

Also diverging from our predictions was that only maternal, and not paternal, control was associated with NA outcomes. Given the paucity of evidence comparing observations of mother- and father- adolescent interactions and their effect on adolescent mood outcomes, it is difficult to explain these differential findings. Yet, one recent study found important parental differences when examining changes in youth perceptions of parent-adolescent relationships throughout adolescence (De Goede, Branje, & Meeus, 2009). For both parents, adolescents’ reports of parental power (i.e., control) in early adolescence were associated with a decline in perceptions of support until mid-adolescence; however, these associations diverged from middle to late adolescence. Specifically, higher maternal power in middle adolescence was still associated with a decline in support over time. For fathers, this link was no longer significant. De Goede et al. suggested that middle adolescents (same approximate age as our youth at the time of study) may view maternal power as particularly intrusive. Given the well-established benefits of parental support on adolescent mood (e.g., Sheeber et al., 2001), De Goede et al.'s study might help explain our differential findings. This maternal-specific effect was also found in the smaller sample of only adolescents with participating mothers and fathers, suggesting that the gender difference is not due to the smaller sample size of fathers. Continued research is necessary to better understand the current findings.

Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

In sum, results showed that higher quality maternal and paternal communication were associated with a decline in NA over time for smokers but not non-smokers. Finally, higher maternal controlling parenting predicted NA escalations for all adolescents. Given that escalation in real-time NA over time is an important predictor of smoking escalation for our entire sample of high-risk adolescents, these parenting results have important theoretical and clinical implications for high-risk youth. As researchers have suggested, the effects of parent-adolescent interactional styles on adolescent smoking may be impacted by unexplored intervening factors (Darling & Cumsille, 2003). We suggest that the influence of parenting on adolescent NA escalation may be one such mechanism. Current smoking intervention efforts that adopt parenting components might consider targeting adolescent NA as an important marker for clinical change. Furthermore, our results indicate that this effect may be moderated by adolescent smoking status, and as we observed with parental control, parent gender. Although we lack the power to test such a moderated meditational model, future researchers might empirically consider this conceptual pathway.

The study had many strengths besides its translational nature, including its longitudinal and multi-method design. Nonetheless, limitations should be noted. First, our study sample was generally at high-risk for smoking escalation, having oversampled for ever smoking, and we must be cautious about generalizing our findings to more normative populations. Future research would also benefit from including a never-smoking control group for additional comparison. Additionally, our initial recruitment yielded only a 36.8% agreement rate, possibly due to the fact that all had to agree to potentially participate in all study components, some of which were time intensive. Although this may somewhat impact generalizability of the results, few factors differentiated the final sample from the invited sample. In addition, the sample size for the present study was relatively small, particularly our fathers, and thus our power was limited. Additional examinations of these associations with larger sample sizes might provide even more valuable translational information. Finally, our NA outcome was created using an average of a week's NA reports, and we thus may be missing out on detecting within-person variability. Nonetheless, our goal was to evaluate a broader picture of change in NA over time, and averaging mood reports fit the needs of the current study.

Despite these limitations, these findings suggest that the quality of parenting in interactions with their high-risk adolescents, specifically their communication style and control, can alter adolescents’ affective trajectories, which in turn, may have considerable impact on smoking throughout adolescence.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (P01CA098262). Dr. Wakschlag was also supported by the Walden & Jean Young Shaw Foundation. We would also like to acknowledge the Family Talk team with special thanks to Joyce Ho, PhD, Aaron Metzger, PhD & Anne Darfler, MA. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Melanie J. Richmond, Institute for Health Research and Policy & Department of Psychology University of Illinois at Chicago 1747 W. Roosevelt Road Chicago, Illinois 60608 (mrichm4@uic.edu)

Robin J. Mermelstein, Institute for Health Research and Policy & Department of Psychology University of Illinois at Chicago 1747 W. Roosevelt Road Chicago, Illinois 60608 (RobinM@uic.edu)

Lauren S. Wakschlag, Department of Medical Social Sciences Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Abbott Hall 710 N. Lake Shore Drive Chicago, Illinois 60611 (lauriew@northwestern.edu)

References

- Arnett JJ. Adolescent storm and stress, reconsidered. American Psychologist. 1999;54:317–326. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.5.317. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.5.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspland H, Gardner F. Observational measures of parent-child interaction: An introductory review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2003;8:136–143. doi: 10.1111/1475-3588.00061. doi: 10.1111/1475-3588.00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Schiff L, Comstock BA. Does avoidant coping influence young adults’ smoking?: A ten-year longitudinal study. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2011;13:998–1002. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr074. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiton MO, Cohen JE, O'Loughlin J, Rehm J. A systematic review of longitudinal studies on the association between depression and smoking in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:356. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-356. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Bronen R, Spencer S, Haut S, Berg A, Oliver P, Tyrer P. Rating scales, scales of measurement, issues of reliability: Resolving some critical issues for clinicians and researchers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:557–564. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000230392.83607.c5. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000230392.83607.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JJ, Rueter MA. Parent-child relationships as systems of support or risk for adolescent suicidality. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:143–155. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.143. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Cumsille P. Theory, measurement, and methods in the study of family influences on adolescent smoking. Addiction. 2003;98(Supplement 1):21–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.3.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1360- 0443.98.s1.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Goede IHA, Branje SJT, Meeus WHJ. Developmental changes in adolescents’ perceptions of relationships with their parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:75–88. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9286-7. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, Eccles JS, Peck S, Malanchuk O. The influence of family relations on trajectories of cigarette and alcohol use from early to late adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.01.005. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ, Berbaum ML, Campbell RT. Modeling mood variation associated with smoking: An application of a heterogeneous mixed-effects model for analysis of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) data. Addiction. 2009;104:297–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02435.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hops H, Tildesley E, Lichtenstein E, Ary D, Sherman L. Parent-adolescent problem-solving interactions and drug use. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1990;16:239–258. doi: 10.3109/00952999009001586. doi: 10.3109/00952999009001586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2008: Volume I, Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 097402) National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2009. Retrieved from http://monitoringthefuture.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Kakihara F, Tilton-Weaver L. Adolescents’ interpretations of parental control: Differentiated by domain and types of control. Child Development. 2009;80:1722–1738. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01364.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Stroud LR, Paronis CA. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: Correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:270–304. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4:231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Fleming CB, Catalano RF. Individual and social influences on progression to daily smoking during adolescence. Pediatrics. 2009;124:895–902. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2015. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Brown RA, Seeley JR, Ramsey SE. Psychosocial correlates of cigarette smoking abstinence, experimentation, persistence and frequency during adolescence. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2000;2:121–131. doi: 10.1080/713688129. doi: 10.1080/713688129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Weisz JR, Wood JJ. Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:986–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.03.001. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig P, Lindahl K, editors. Family observational coding systems: Resources for systematic research. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond MJ, Mermelstein RJ, Metzger A. Heterogeneous friendship affiliation, problem behaviors, and emotional outcomes among high-risk adolescents. Prevention Science. 2012;13:267–277. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0261-2. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0261-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Conger RD. Intergenerational continuity of hostile parenting and its consequences: The moderating influence of children's negative emotional reactivity. Social Development. 2003;12:420–439. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00241. [Google Scholar]

- Schneiders J, Nicolson NA, Berkhof J, Feron FJ, deVries MW, van Os J. Mood in daily contexts: Relationship with risk in early adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:697–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00543.x. [Google Scholar]

- Schneiders J, Nicolson NA, Berkhof J, Feron FJ, van Os J, deVries MW. Mood reactivity to daily negative events in early adolescence: Relationship to risk for psychopathology. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:543–554. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.3.543. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I, Klessinger N. Long-term effects of avoidant coping on adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:617–630. doi: 10.1023/A:1026440304695. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Davis B, Leve C, Hops H, Tildesley E. Adolescents’ relationships with their mothers and fathers: Associations with depressive disorder and subdiagnostic symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:144–154. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.144. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber L, Hops H, Alpert A, Davis B, Andrews J. Family support and conflict: Prospective relations to adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:333–344. doi: 10.1023/a:1025768504415. doi: 10.1023/A:1025768504415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber L, Hops H, Davis B. Family processes in adolescent depression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2001;4:19–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1009524626436. doi: 10.1023/A:1009524626436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Farhat T. Recent findings on peer group influences on adolescent smoking. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2010;31:191–208. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0220-x. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0220-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:1–19. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00001. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Barrera M, Jr., Chassin L. Relation of parental support and control to adolescents’ externalizing symptomatology and substance use: A longitudinal examination of curvilinear effects. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:609–629. doi: 10.1007/BF00916446. doi: 10.1007/BF00916446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag L, Chase-Lansdale PL, Brooks-Gunn J. Not just “ghosts in the nursery”: Contemporaneous intergenerational relationships and parenting in young African-American families. Child Development. 1996;67:2131–2147. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01848.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Metzger A, Darfler A, Ho J, Mermelstein R, Rathouz PJ. The family talk about smoking (FTAS) paradigm: New directions for assessing parent-teen communications about smoking. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2011;13:103–112. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq217. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein SM, Mermelstein RJ, Hankin BL, Hedeker D, Flay BR. Longitudinal patterns of daily affect and global mood during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:587–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00536.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA. Supportive functions of interpersonal relationships. In: Cohen S, Syme SL, editors. Social support and health. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1985. pp. 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Cleary SD. How are social support effects mediated? A test with parental support and adolescent substance use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:937–952. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.5.937. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.5.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Filer M. Stress-coping model of adolescent substance use. In: Ollendick TH, Prinz RJ, editors. Advances in clinical child psychology. Vol. 18. Plenum; New York: 1996. pp. 91–132. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Windle RC. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among middle adolescents: Prospective associations and intrapersonal and interpersonal influences. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:215–226. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.2.215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]