Summary

N-acetyllactosaminyl glycans are key regulators of the vitality and effector function of anti-tumor T cells. When galectin-1 (Gal-1) binds N-acetyllactosamines on select membrane glycoproteins on anti-tumor T cells, these cells either undergo apoptosis or become immunoregulatory. Methods designed to antagonize expression or function of these N-acetyllactosamines on N- and O-glycans have thus intensified. Since tumors can produce an abundance of Gal-1, Gal-1 is considered a critical factor for protecting tumor cells from T cell-mediated anti-tumor activity. Recent efforts have capitalized on the anti-N-acetyllactosamine action of fluorinated glucosamines to treat anti-tumor T cells, resulting in diminished Gal-1-binding and higher anti-tumor T cell levels. In this perspective, the prospect of fluorinated glucosamines in eliminating N-acetyllactosamines on anti-tumor T cells to boost anti-tumor immunity is presented.

Keywords: Galectin-1, Glucosamine, Anti-tumor T cell Immunity, Galectin-1 Ligands

A. Historical View of Fluorinated Glucosamine Analogs in Pharmaceutical Development

Nearly 35-years ago, acetylated and fluorinated derivatives of D-glucosamine were synthesized and evaluated as cytotoxic anti-cancer agents [1–3]. The intent was to create analogs of natural-occurring hexosamines that could passively enter cancer cells, compete for nucleotide precursors and inhibit ongoing glycoconjugate and RNA/DNA synthesis pathways [1–3]. This metabolic antagonism could thus potentially alter the expression of cell surface glycoconjugates and/or attenuate cell proliferation. As such, it was proposed that glucosamine analog treatment could change the antigenicity of cancer cell surface and boost immune-mediated mechanisms or simply block cancer growth. Indeed, though evidence suggested that these glucosamine analogs could be metabolized by cancer cells [1–3], precisely how they blocked glycan formation or whether nucleotide-sugar analog conjugates were even formed and utilized by glycosyltransferases to incorporate into growing oligosaccharide chains was still unknown.

It was later shown that, at non-growth inhibitory concentrations, the fully acetylated and 4-fluorinated glucosamine analog, 2-acetamido-2,4-dideoxy-1,3,6-tri-O-acetyl-4-fluoro-D-glucopyranose (4-F-GlcNAc), could alter the structure and function of N- and O-glycans on ovarian and colon cancer cell glycoproteins [2,4–8]. These alterations inhibited human ovarian cancer (OCa) and colon cancer (CCa) cell binding to galectin-1 (Gal-1) and endothelial (E)-selectin, respectively [2,4–8]. These results provided hope that modulating N-acetyllactosamine (galactose β1,4 N-acetylglucosamine) synthesis essential for both Gal-1- and E-selectin-binding activity, could actually interfere with lectin-mediated cell adhesion events critically involved in the metastatic process. In fact, because OCa cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix underlying the peritoneal lining and CCa cell trafficking to liver are, in part, mediated by Gal-1 and E-selectin, respectively, there remains much promise for these sugar analogs to be developed as anti-metastatic therapeutics [4–18]. Nevertheless, these results offered the experimental rationale for targeting glyco-metabolically active cells distinct from cancer cells, where glycoconjugate processing and function provide key cell behavioral features without posing a significant threat to cell viability.

Subsequent research on fluorinated glucosamine analogs transitioned in intent to altering key glycan-recognition determinants on skin-homing T cells that initiate their entry into skin [19]. Effector/memory T cells educated to enter dermal tissues require the E-selectin-binding glycan, sialyl Lewis X, for binding E-selectin constitutively expressed on dermal microvessels and for initiating a cascade of adhesive events that facilitates diapedesis. Given evidence on E-selectin-binding glycan downregulation in 4-F-GlcNAc-treated CCa cells, it was hypothesized that 4-F-GlcNAc treatment could inhibit sialyl Lewis X synthesis on skin-homing T cells and block E-selectin-mediated adhesion to dermal microvessels and recruitment into inflamed skin. Indeed, studies showed that antigen-dependent CD4+ T cell activation in skin-draining lymph nodes triggered sialyl Lewis X biosynthesis that conferred a susceptibility to 4-F-GlcNAc antagonism [19,20]. Treatment with 4-F-GlcNAc reduced the level of sialyl Lewis X and corresponding E-selectin-binding activity, which blunted antigen-dependent T cell-mediated inflammation in the skin [9–22]. These inhibitory effects were similarly found on human leukemic cells treated with a peracetylated 4-fluorinated N-acetylgalactosamine analog [23].

To understand more globally the anti-carbohydrate effects on T cells by fluorinated glucosamine analogs, further evaluations focused on analysis of Gal-1 binding to T cells following 4-F-GlcNAc treatment. Considering Gal-1’s key role in binding and inducing apoptosis or immunoregulatory activity in effector CD4+ T cells [24–30], understanding the relative difference between inhibition of Gal-1-binding and E-selectin-binding was an important distinction to ascertain. It can be construed that inhibiting the N-acetyllactosamine lattice required for Gal-1-mediated inflammatory silencing of activated/effector T cells may paradoxically offset a deficit in T cell trafficking due to lowering of E-selectin-binding glycans. It was, in fact, demonstrated that the expression of Gal-1-binding glycans on activated CD4+ T cells was more sensitive than E-selectin-binding glycans to 4-F-GlcNAc treatment [31]. In support of this observation, earlier studies analyzing the specificity of glycoconjugate action showed that 4-F-GlcNAc preferentially limits the synthesis of N-acetyllactosamines in N- and O-glycans on glycoproteins and not on neolactoglycosphingolipids, which can also function as E-selectin-binding glycans [19–21,31–35].

Collectively, these findings suggested that Gal-1-binding glycans and related triggering of downstream immune tolerogenic pathways may be a more amenable target for 4-F-GlcNAc treatment. This notion posed new questions on how 4-F-GlcNAc can most effectively be used for N-acetyllactosamine antagonism and whether 4-F-GlcNAc should indeed be developed as an anti-inflammatory therapeutic. We have thusly postulated that interfering with the synthesis of Gal-1-binding glycans in effector T cells would be perhaps more applicable in the context of cancer immunotherapy, whereby anti-tumor T cells treated with 4-F-GlcNAc would be resistant to Gal-1-mediated tumor immune evasion [31].

B. Mechanism of Fluorinated Glucosamine Anti-Carbohydrate Action

Early evidence suggested that fully acetylated variants of glucosamine could effectively traverse a cancer cell’s plasma membrane and sequester endogenous UTP and CTP pools necessary for steady-state RNA/DNA biosynthesis, which elicited a cytotoxic effect in cancer cells [2,3]. Furthermore, it was found that diversion of endogenous UTP pools by exogenous glucosamine analog treatments could elevate UDP-N-acetylglucosamine levels, thereby lowering native pools of other nucleotide-sugars, such as UDP-galactose and UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine needed for N- and O-glycan extension [2,3].

Fluorinated glucosamine analogs were synthesized by addition of a fluorine atom, which cannot form a glycosidic bond, at strategic pyranose ring carbons that could potentially antagonize oligosaccharide elongation [1–3]. As such, by substituting fluorine for a hydroxyl group at the carbon-4 position, it was theorized that, upon entering a cell and incorporation into a growing poly-N-acetyllactosaminyl chain, 4-F-GlcNAc could block glycosidic bonding of a galactose residue at the carbon-4 position. All data on the anti-glycoconjugate effects of 4-F-GlcNAc efficacy subsequently, in fact, indicated that synthesis of (galactose β1,4 N-acetylglucosamine)n residues and related sialyl Lewis X moieties were inhibited [19–22]. More recent structural data provided a more refined assessment in that N-acetyllactosamines and sialyl Lewis X on N-glycans and on core 2 O-glycans were reduced and the content and structural diversity of tri- and tetra-antennary N-glycans and of O-glycans were reduced, while biantennary N-glycans were increased. However, MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis did not reveal any m/z ratios relating to the presence of fluorine atoms in N- and O-glycans released from 4-F-GlcNAc-treated human T cells and leukemic cells, indicating that 4-F-GlcNAc did not in fact incorporate into and truncate glycan chains [31]. 4-F-GlcNAc treatment also neither affected the expression nor activity of N-acetyllactosamine-synthesizing enzymes or the level of sialyl Lewis X on glycolipids [31]. As expected though, 4-F-GlcNAc did significantly reduce intracellular levels of UDP-GlcNAc [31], which was validated by another group assessing the mechanism of acetylated and fluorinated glucosamine analog action [36]. What was also noted from this recent work was the first evidence of UDP-4-F-GlcNAc donor sugar in 4-F-GlcNAc-treated cancer cells [36].

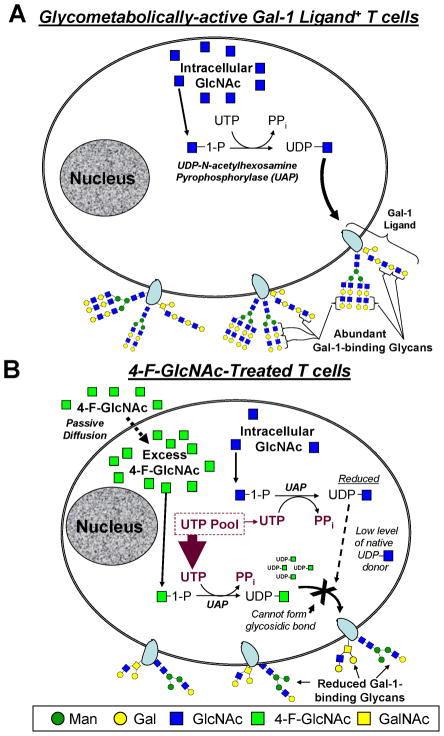

Cumulatively, data on fluorinated glucosamine action and 4-F-GlcNAc anti-carbohydrate efficacy indicate that Gal-1- and E-selectin-binding reductions are not caused by direct 4-F-GlcNAc incorporation into oligosaccharides and consequent chain termination, but rather by shunting endogenous UDP-GlcNAc synthesis towards production of UDP-4-F-GlcNAc (Figure 1). In that there is no evidence of glycan incorporation of fluorinated analogs, the fluorine residue at the carbon-4 position in UDP-4-F-GlcNAc is likely hindering the ability of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferases to transfer the 4-F-GlcNAc sugar to an oligosaccharide acceptor [31,36]. Alternatively, in addition to titrating out pools of UTP, another potential mode of action is that 4-F-GlcNAc is irreversibly binding and inactivating UDP-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase (UAP) directly. These possibilities need to be investigated further.

Figure 1. Mechanism of Peracetylated 4-Fluorinated Glucosamine Anti-Carbohydrate Action.

(A) T cells actively synthesizing cell surface glycoconjugates are sensitive to glyco-metabolic antagonists, such as fully acetylated 4-F-GlcNAc. (B) Following passive cellular entry and deacetylation of peracetylated 4-fluorinated-glucosamine, 4-F-GlcNAc is phosphorylated and conjugated to UTP by UDP-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase (UAP). Depending on the cytosolic concentration of 4-F-GlcNAc, endogenous UDP-GlcNAc levels are compromised due to sequestration of UTP. This shunting effect causes reductions in N-acetyllactosamines necessary for extending and branching of N- and O-glycan antennae characteristically bound by Gal-1.

C. Blocking N-acetyllactosamine Synthesis in CD8+ T cells to Improve Anti-tumor Immunity

The presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, in particular, CTLs, and their implication in cancer patient survival and prognosis is not clear [37–40]. Moreover, adoptive transfer of autologous anti-melanoma CTLs has shown only a modest improvement in patients with advanced disease [41–43]. These observations suggest that melanomas can innately avert the immune system. Galectins, in particular Gal-1 and Gal-3, have been shown to be produced at high levels by melanoma cells [44–46] as well as certain lymphomas, such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma [47–49] and cutaneous T cell lymphoma [27], and found to elicit potent immunosuppressive features [27,47,48,50]. In fact melanoma-derived Gal-1 has been shown to efficiently subdue the effector function of T helper (Th) 1 and Th17 cell subsets as well as CTLs [28,29,50], all of which express a high level of Gal-1-binding N-acetyllactosamines. Since Gal-1 characteristically binds effector CD4+ T cells with anti-tumor activity and CTLs and causes apoptosis/tolerization, we have hypothesized that reducing Gal-1-binding to N-acetyllactosamines on anti-tumor T cells could significantly elevate anti-tumor T cell immune activity, particularly against tumors that express copious amounts of Gal-1.

Accordingly, most recent efforts in 4-F-GlcNAc development have centered on anti-tumor studies with the intent of lowering Gal-1-binding glycans, alleviating Gal-1-dependent immunoregulation and boosting anti-tumor T cell immunity. Our laboratory has accumulated some exciting new in vivo data on the use of 4-F-GlcNAc to treat melanomas and lymphomas. Melanoma was not only included as a tumor model based on its high Gal-1 expression, but that diminution of E-selectin-binding glycan would be inconsequential. Since microvessels within melanomas do not express E-selectin [51], 4-F-GlcNAc-treated T cells could theoretically still infiltrate melanomas while evading Gal-1-dependent control to elicit their effector function. Using non-toxic doses of 4-F-GlcNAc in mice bearing melanoma or lymphoma, we found that tumor growth was grossly attenuated [52]. These results were, in part, due to 4-F-GlcNAc-dependent sparing of Gal-1-mediated apoptosis of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells and of melanoma specific CTLs by reducing their surface content of Gal-1-binding N-acetyllactosamines. In other words, there was a shift in the effector - regulatory T cell balance towards more Th1 and Th17 cells and more CTLs, and less immune regulating IL-10+ T cells generated by tumor-derived Gal-1 [26,27,52]. These findings reinforced the importance of N-acetyllactosamines in controlling the fate and function of effector CD4+ T cell and CTL subsets and indicated that treating melanomas and lymphomas, which abundantly express Gal-1 and likely other immunosuppressive galectins, with 4-F-GlcNAc could prove to be therapeutically efficacious [52]. In all, these data highlight the promise of 4-F-GlcNAc to limit tumor growth by boosting T cell-mediated immunity [53].

D. Conclusion and Future Prospects of Fluorinated Glucosamine Analogs

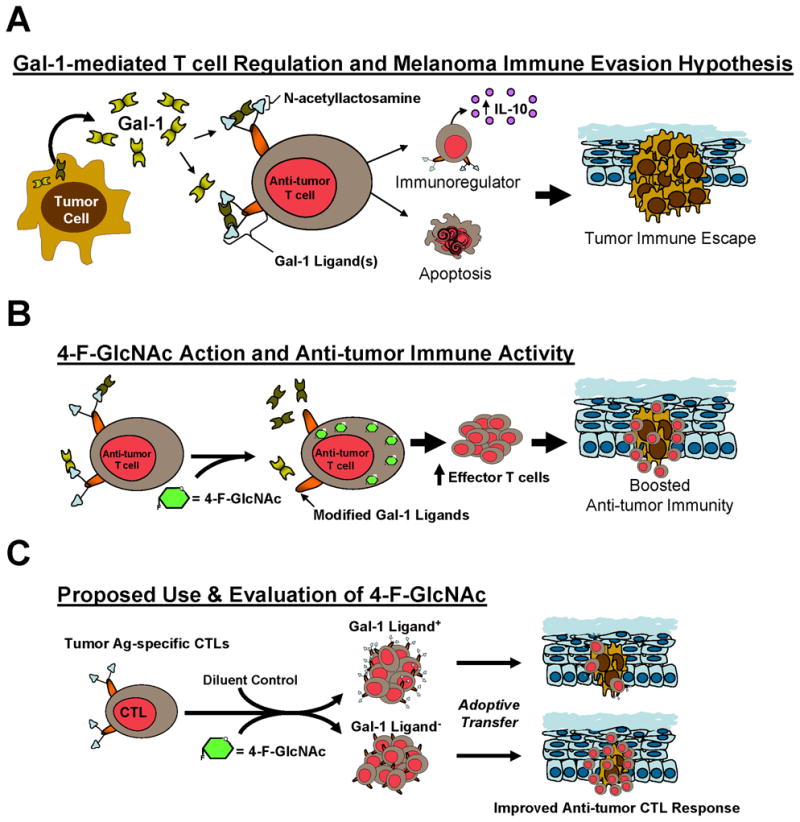

There exists a long standing history on the development of fluorinated glucosamine analogs for the metabolic antagonism of glycoconjugate and DNA/RNA synthesis. While early studies focused on the merits of cytotoxic-induction in cancer cells by 4-F-GlcNAc, subsequent efforts re-considered these intents and began to evaluate the targeting of glyco-metabolically-active T cells. In this case, the main objective was to selectively target these T cells, which could rapidly uptake glucosamine analogs to antagonize UDP-GlcNAc production and block the synthesis of sialyl Lewis X necessary for E-selectin-mediated trafficking to inflamed skin. During attempts to illuminate the mechanism of 4-F-GlcNAc-glycan alterations and lectin-binding activities, it was appreciated that Gal-1-binding was more efficiently inhibited than E-selectin-binding activity. These results encouraged later efforts to evaluate 4-F-GlcNAc as an inhibitor of Gal-1-binding N-acetyllactosamine synthesis in T cells and blocker of the immunoregulatory control of tumor-derived Gal-1 (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Neutralization of the Gal-1 – Gal-1 ligand axis to Boost Anti-tumor T cell Immunity.

(A) A schematic depiction of tumor immune evasion model in which melanoma-derived Gal-1 can antagonize the anti-tumor efficacy of T cells. (B) A cartoon depiction of the metabolic antagonism of Gal-1-binding N-acetyllactosamine synthesis in effector anti-tumor T cells caused by 4-F-GlcNAc and consequent enhancement of anti-tumor immunity. (C) A schematic overview of a novel cancer immunotherapeutic strategy to selectivity target donor CTLs with 4-F-GlcNAc for escaping Gal-1 control and improving the efficacy of adoptive T cell therapy.

As such, studies from our laboratory showed that 4-F-GlcNAc elicited potent anti-tumor activity by increasing the quantity of effector T cells and reducing the level of immune regulating IL-10+ T cells characteristically generated by tumor-derived Gal-1 [26,27,52,53] (Figure 2B). However, much skepticism remains as this mode of therapy could theoretically alter glycosylation in other glyco-metabolically-active leukocytes, such as activated antigen-presenting cells and hematopoietic progenitor cells, wherein lectin-binding events are known to affect their immunologic behavior [54–57]. Future studies are needed to ascertain the relative specificity of anti-glycosylation effects on non-T cells in 4-F-GlcNAc-treated animals.

As a prospective approach, which provides ultimate targeting efficiency, we are pursuing efforts to study 4-F-GlcNAc in the setting of adoptive T cell cancer therapy. Adoptive transfer of autologous tumor-specific CTLs as an anti-cancer therapy is a promising, though imperfect, approach to boost anti-tumor immunity [58–60]. We believe that 4-F-GlcNAc treatment of in vitro-expanded tumor Ag-specific CTLs will generate CTLs lacking not only Gal-1-binding N-acetyllactosamines but potentially Gal-9-binding TIM-3 and other immunoregulatory galectin ligands, enhancing their tumoricidal activity due to their insensitivity to galectin(s)-dependent regulation (Figure 2C). Since CTLs express an abundance of N-acetyllactosamines, tailoring 4-F-GlcNAc treatment with this ex vivo approach could improve the quantity, longevity and anti-tumor activity of CTLs, particularly against tumors that overexpress Gal-1, Gal-9 and other immunoregulatory galectins. Whereas a neutralizing antibody against a single galectin could help alleviate respective galectin-dependent immunoregulation, 4-F-GlcNAc’s ability to potentially inhibit the synthesis of Gal-1, Gal-3 and Gal-9 binding glycans on CTLs could indeed offer a multifaceted strategy, in which multiple galectin regulators are neutralized [53]. This N-acetyllactosamine reduction strategy could even be advantageous to help boost the potency of cancer vaccines or viral vaccines for other diseases, wherein tumor- and virus-specific CTLs are key regulators of an efficacious immunologic response, though have been shown to be negatively regulated by Gal-9 [61,62]. Moreover, combining 4-F-GlcNAc with a vaccine delivery method, such as skin scarification, can perhaps synergize the efficacy of immunologic response and help maintain protective immunity [63,64]. The mechanism and functional consequences of 4-F-GlcNAc efficacy on CTLs have reinvigorated the prospect of using fluorinated glucosamines as a novel immunotherapeutic adjuvant for treating cancer and for boosting vaccine efficacy against infectious diseases.

Highlights.

Galectin-1 (Gal-1) is commonly expressed at a high level by tumor cells and causes immune suppression of anti-tumor T cells.

Gal-1 – Gal-1-binding carbohydrate interactions play a pivotal role in shaping the effector function of anti-tumor T cells.

Gal-1-binding carbohydrates, known as N-acetyllactosaminyl glycans, are targetable entities on anti-tumor T cells.

Fluorinated glucosamine analogs are effective metabolic inhibitors of N-acetyllactosamine formation and, thus,

potentially efficacious methods for thwarting Galectin-1-mediated immune suppression of effector anti-tumor T cells.

Acknowledgments

I thank Drs. Ralph Bernacki, Barbara Woynarowska, Moheswar Sharma, E.V. Chandrasekaran, Khushi Matta, Robert Sackstein and Joseph Lau for their mentorship and early teachings in glycobiology. This work is dedicated to their efforts for opening new research directions in lectin biology and for enhancing our glyco-pathobiological understanding of inflammation and cancer metastasis. Research in the Dimitroff Laboratory is funded by an RO1 AT004628 grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bernacki R, Porter C, Korytnyk W, Mihich E. Plasma membrane as a site for chemotherapeutic intervention. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1977;16:217–237. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(78)90075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernacki RJ, Sharma M, Porter NK, Rustum Y, Paul B, Korythyk W. Biochemical characteristics, metabolism, and antitumor activity of several acetylated hexosamines. J Supramol Struct. 1977;7:235–250. doi: 10.1002/jss.400070208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma M, Bernacki RJ, Paul B, Korytnyk W. Fluorinated carbohydrates as potential plasma membrane modifiers. Synthesis of 4- and 6-fluoro derivatives of 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-D-hexopyranoses. Carbohydr Res. 1990;198:205–221. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(90)84293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimitroff CJ, Pera P, Dall’Olio F, Matta KL, Chandrasekaran EV, Lau JT, Bernacki RJ. Cell surface n-acetylneuraminic acid alpha2,3-galactoside-dependent intercellular adhesion of human colon cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;256:631–636. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimitroff CJ, Sharma A, Bernacki RJ. Cancer metastasis: a search for therapeutic inhibition. Cancer Invest. 1998;16:279–290. doi: 10.3109/07357909809039778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skrincosky DM, Allen HJ, Bernacki RJ. Galaptin-mediated adhesion of human ovarian carcinoma A121 cells and detection of cellular galaptin-binding glycoproteins. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2667–2675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woynarowska B, Dimitroff CJ, Sharma M, Matta KL, Bernacki RJ. Inhibition of human HT-29 colon carcinoma cell adhesion by a 4-fluoro-glucosamine analogue. Glycoconj J. 1996;13:663–674. doi: 10.1007/BF00731455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woynarowska B, Skrincosky DM, Haag A, Sharma M, Matta K, Bernacki RJ. Inhibition of lectin-mediated ovarian tumor cell adhesion by sugar analogs. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22797–22803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bresalier RS, Byrd JC, Brodt P, Ogata S, Itzkowitz SH, Yunker CK. Liver metastasis and adhesion to the sinusoidal endothelium by human colon cancer cells is related to mucin carbohydrate chain length. Int J Cancer. 1998;76:556–562. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980518)76:4<556::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gangopadhyay A, Lazure DA, Thomas P. Adhesion of colorectal carcinoma cells to the endothelium is mediated by cytokines from CEA stimulated Kupffer cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1998;16:703–712. doi: 10.1023/a:1006576627429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gout S, Tremblay PL, Huot J. Selectins and selectin ligands in extravasation of cancer cells and organ selectivity of metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008;25:335–344. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irimura T, Ota M, Kawamura Y, Nemoto-Sasaki Y. Carbohydrate-mediated adhesion of human colon carcinoma cells to human liver sections. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;491:403–412. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1267-7_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitakata H, Nemoto-Sasaki Y, Takahashi Y, Kondo T, Mai M, Mukaida N. Essential roles of tumor necrosis factor receptor p55 in liver metastasis of intrasplenic administration of colon 26 cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6682–6687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kruskal JB, Azouz A, Korideck H, El-Hallak M, Robson SC, Thomas P, Goldberg SN. Hepatic colorectal cancer metastases: imaging initial steps of formation in mice. Radiology. 2007;243:703–711. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2432060604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opolski A, Laskowska A, Madej J, Wietrzyk J, Klopocki A, Radzikowski C, Ugorski M. Metastatic potential of human CX-1 colon adenocarcinoma cells is dependent on the expression of sialosyl Le(a) antigen. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1998;16:673–681. doi: 10.1023/a:1006502009682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.St Hill CA, Farooqui M, Mitcheltree G, Gulbahce HE, Jessurun J, Cao Q, Walcheck B. The high affinity selectin glycan ligand C2-O-sLex and mRNA transcripts of the core 2 beta-1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (C2GnT1) gene are highly expressed in human colorectal adenocarcinomas. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuiji H, Nakatsugawa S, Ishigaki T, Irimura T. Malignant and other properties of human colon carcinoma cells after suppression of sulfomucin production in vitro. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1999;17:97–104. doi: 10.1023/a:1006654027742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weston BW, Hiller KM, Mayben JP, Manousos GA, Bendt KM, Liu R, Cusack JC., Jr Expression of human alpha(1,3)fucosyltransferase antisense sequences inhibits selectin-mediated adhesion and liver metastasis of colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2127–2135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dimitroff CJ, Bernacki RJ, Sackstein R. Glycosylation-dependent inhibition of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen expression: implications in modulating lymphocyte migration to skin. Blood. 2003;101:602–610. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dimitroff CJ, Kupper TS, Sackstein R. Prevention of leukocyte migration to inflamed skin with a novel fluorosugar modifier of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1008–1018. doi: 10.1172/JCI19220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Descheny L, Gainers ME, Walcheck B, Dimitroff CJ. Ameliorating skin-homing receptors on malignant T cells with a fluorosugar analog of N-acetylglucosamine: P-selectin ligand is a more sensitive target than E-selectin ligand. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2065–2073. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gainers ME, Descheny L, Barthel SR, Liu L, Wurbel MA, Dimitroff CJ. Skin-homing receptors on effector leukocytes are differentially sensitive to glyco-metabolic antagonism in allergic contact dermatitis. J Immunol. 2007;179:8509–8518. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marathe DD, Buffone A, Jr, Chandrasekaran EV, Xue J, Locke RD, Nasirikenari M, Lau JT, Matta KL, Neelamegham S. Fluorinated per-acetylated GalNAc metabolically alters glycan structures on leukocyte PSGL-1 and reduces cell binding to selectins. Blood. 2010;115:1303–1312. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-231480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perillo NL, Pace KE, Seilhamer JJ, Baum LG. Apoptosis of T cells mediated by galectin-1. Nature. 1995;378:736–739. doi: 10.1038/378736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cedeno-Laurent F, Barthel SR, Opperman MJ, Lee DM, Clark RA, Dimitroff CJ. Development of a nascent galectin-1 chimeric molecule for studying the role of leukocyte galectin-1 ligands and immune disease modulation. J Immunol. 2010;185:4659–4672. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **26.Cedeno-Laurent F, Opperman M, Barthel SR, Kuchroo VK, Dimitroff CJ. Galectin-1 triggers an immunoregulatory signature in th cells functionally defined by IL-10 expression. J Immunol. 2012;188:3127–3137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103433. This is the first that shows how galectin-1 can bind trigger the synthesis of immunoregulatory cytokine, IL-10, on undifferentiated and polarized Th cell subsets. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **27.Cedeno-Laurent F, Watanabe R, Teague JE, Kupper TS, Clark RA, Dimitroff CJ. Galectin-1 inhibits the viability, proliferation, and Th1 cytokine production of nonmalignant T cells in patients with leukemic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2012;119:3534–3538. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-396457. This study shows that leukemic cell-derived galectin-1 can skew the production and effector phenotype of benign Th cell subsets in patients with leukemic-CTCL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ilarregui JM, Croci DO, Bianco GA, Toscano MA, Salatino M, Vermeulen ME, Geffner JR, Rabinovich GA. Tolerogenic signals delivered by dendritic cells to T cells through a galectin-1-driven immunoregulatory circuit involving interleukin 27 and interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:981–991. doi: 10.1038/ni.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toscano MA, Bianco GA, Ilarregui JM, Croci DO, Correale J, Hernandez JD, Zwirner NW, Poirier F, Riley EM, Baum LG, et al. Differential glycosylation of TH1, TH2 and TH-17 effector cells selectively regulates susceptibility to cell death. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:825–834. doi: 10.1038/ni1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Leij J, van den Berg A, Blokzijl T, Harms G, van Goor H, Zwiers P, van Weeghel R, Poppema S, Visser L. Dimeric galectin-1 induces IL-10 production in T-lymphocytes: an important tool in the regulation of the immune response. J Pathol. 2004;204:511–518. doi: 10.1002/path.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **31.Barthel SR, Antonopoulos A, Cedeno-Laurent F, Schaffer L, Hernandez G, Patil SA, North SJ, Dell A, Matta KL, Neelamegham S, et al. Peracetylated 4-fluoro-glucosamine reduces the content and repertoire of N- and O-glycans without direct incorporation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:21717–21731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.194597. This study shows for the first time that 4-fluoroglucosamine analogs elicit their anti-carbohydrate action by antagonizing the production of UDP-GlcNAc involved in N-acetyllactosamine formation on N- and O-glycans. This in contrast to their hypothesized mode of efficacy whereby they are biosynthetically incorporated into growing oligosaccharide chains to and act as chain terminators. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barthel SR, Gavino JD, Wiese GK, Jaynes JM, Siddiqui J, Dimitroff CJ. Analysis of glycosyltransferase expression in metastatic prostate cancer cells capable of rolling activity on microvascular endothelial (E)-selectin. Glycobiology. 2008;18:806–817. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barthel SR, Wiese GK, Cho J, Opperman MJ, Hays DL, Siddiqui J, Pienta KJ, Furie B, Dimitroff CJ. Alpha 1,3 fucosyltransferases are master regulators of prostate cancer cell trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19491–19496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906074106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dimitroff CJ, Descheny L, Trujillo N, Kim R, Nguyen V, Huang W, Pienta KJ, Kutok JL, Rubin MA. Identification of leukocyte E-selectin ligands, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 and E-selectin ligand-1, on human metastatic prostate tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5750–5760. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dimitroff CJ, Lechpammer M, Long-Woodward D, Kutok JL. Rolling of human bone-metastatic prostate tumor cells on human bone marrow endothelium under shear flow is mediated by E-selectin. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5261–5269. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishimura SI, Hato M, Hyugaji S, Feng F, Amano M. Glycomics for Drug Discovery: Metabolic Perturbation in Androgen-Independent Prostate Cancer Cells Induced by Unnatural Hexosamine Mimics. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;124:1–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clemente CG, Mihm MC, Jr, Bufalino R, Zurrida S, Collini P, Cascinelli N. Prognostic value of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in the vertical growth phase of primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 1996;77:1303–1310. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960401)77:7<1303::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mihm MC, Jr, Clemente CG, Cascinelli N. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in lymph node melanoma metastases: a histopathologic prognostic indicator and an expression of local immune response. Lab Invest. 1996;74:43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oble DA, Loewe R, Yu P, Mihm MC., Jr Focus on TILs: prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in human melanoma. Cancer Immun. 2009;9:3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liakou CI, Narayanan S, Ng Tang D, Logothetis CJ, Sharma P. Focus on TILs: Prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in human bladder cancer. Cancer Immun. 2007;7:10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Besser MJ, Shapira-Frommer R, Treves AJ, Zippel D, Itzhaki O, Hershkovitz L, Levy D, Kubi A, Hovav E, Chermoshniuk N, et al. Clinical responses in a phase II study using adoptive transfer of short-term cultured tumor infiltration lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2646–2655. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dudley ME, Gross CA, Langhan MM, Garcia MR, Sherry RM, Yang JC, Phan GQ, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Citrin DE, et al. CD8+ enriched “young” tumor infiltrating lymphocytes can mediate regression of metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6122–6131. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dudley ME, Yang JC, Sherry R, Hughes MS, Royal R, Kammula U, Robbins PF, Huang J, Citrin DE, Leitman SF, et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5233–5239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vereecken P, Awada A, Suciu S, Castro G, Morandini R, Litynska A, Lienard D, Ezzedine K, Ghanem G, Heenen M. Evaluation of the prognostic significance of serum galectin-3 in American Joint Committee on Cancer stage III and stage IV melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 2009;19:316–320. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32832ec001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radosavljevic G, Jovanovic I, Majstorovic I, Mitrovic M, Lisnic VJ, Arsenijevic N, Jonjic S, Lukic ML. Deletion of galectin-3 in the host attenuates metastasis of murine melanoma by modulating tumor adhesion and NK cell activity. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2011;28:451–462. doi: 10.1007/s10585-011-9383-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mourad-Zeidan AA, Melnikova VO, Wang H, Raz A, Bar-Eli M. Expression profiling of Galectin-3-depleted melanoma cells reveals its major role in melanoma cell plasticity and vasculogenic mimicry. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1839–1852. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodig SJ, Ouyang J, Juszczynski P, Currie T, Law K, Neuberg DS, Rabinovich GA, Shipp MA, Kutok JL. AP1-dependent galectin-1 expression delineates classical hodgkin and anaplastic large cell lymphomas from other lymphoid malignancies with shared molecular features. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3338–3344. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Juszczynski P, Ouyang J, Monti S, Rodig SJ, Takeyama K, Abramson J, Chen W, Kutok JL, Rabinovich GA, Shipp MA. The AP1-dependent secretion of galectin-1 by Reed Sternberg cells fosters immune privilege in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13134–13139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706017104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gandhi MK, Moll G, Smith C, Dua U, Lambley E, Ramuz O, Gill D, Marlton P, Seymour JF, Khanna R. Galectin-1 mediated suppression of Epstein-Barr virus specific T-cell immunity in classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2007;110:1326–1329. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-066100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rubinstein N, Alvarez M, Zwirner NW, Toscano MA, Ilarregui JM, Bravo A, Mordoh J, Fainboim L, Podhajcer OL, Rabinovich GA. Targeted inhibition of galectin-1 gene expression in tumor cells results in heightened T cell-mediated rejection; A potential mechanism of tumor-immune privilege. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:241–251. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weishaupt C, Munoz KN, Buzney E, Kupper TS, Fuhlbrigge RC. T-cell distribution and adhesion receptor expression in metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2549–2556. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **52.Cedeno-Laurent F, Opperman MJ, Barthel SR, Hays D, Schatton T, Zhan Q, He X, Matta KL, Frank MH, Supko JG, et al. Metabolic inhibition of galectin-1-binding carbohydrates accentuates anti-tumor immunity. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:410–420. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.335. This landmark study establishes the in vivo anti-tumor immune activity by 4-fluoroglucosamine by increasing levels of effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, including tumor-specific CD8+ T cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **53.Cedeno-Laurent F, Dimitroff CJ. Galectins and their ligands: negative regulators of anti-tumor immunity. Glycoconjugate J. Apr 29; doi: 10.1007/s10719-012-9379-0. This review highlights the literature and prospect of antagoninzing galectin-1 - galectin-1 ligand interactions to improve anti-tumor immunity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *54.Rabinovich GA, Croci DO. Regulatory circuits mediated by lectin-glycan interactions in autoimmunity and cancer. Immunity. 2012;36:322–335. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.004. This review is a comprehensive view on the role of lectins in regulating immune activity and tumor progression and metastasis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rabinovich GA, Vidal M. Galectins and microenvironmental niches during hematopoiesis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2012;18:443–451. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32834bab18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sackstein R. The biology of CD44 and HCELL in hematopoiesis: the ‘step 2-bypass pathway’ and other emerging perspectives. Curr Opin Hematol. 2011;18:239–248. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283476140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Winkler IG, Snapp KR, Simmons PJ, Levesque JP. Adhesion to E-selectin promotes growth inhibition and apoptosis of human and murine hematopoietic progenitor cells independent of PSGL-1. Blood. 2004;103:1685–1692. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Butler MO, Ansen S, Tanaka M, Imataki O, Berezovskaya A, Mooney MM, Metzler G, Milstein MI, Nadler LM, Hirano N. A panel of human cell-based artificial APC enables the expansion of long-lived antigen-specific CD4+ T cells restricted by prevalent HLA-DR alleles. Int Immunol. 2010;22:863–873. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *59.Butler MO, Friedlander P, Milstein MI, Mooney MM, Metzler G, Murray AP, Tanaka M, Berezovskaya A, Imataki O, Drury L, et al. Establishment of antitumor memory in humans using in vitro-educated CD8+ T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:80ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002207. This study revels the prospect of using in vitro-generated melanoma-specific CD8+ T cells for the treatment of malignant melanoma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Butler MO, Lee JS, Ansen S, Neuberg D, Hodi FS, Murray AP, Drury L, Berezovskaya A, Mulligan RC, Nadler LM, et al. Long-lived antitumor CD8+ lymphocytes for adoptive therapy generated using an artificial antigen-presenting cell. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1857–1867. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jin HT, Anderson AC, Tan WG, West EE, Ha SJ, Araki K, Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK, Ahmed R. Cooperation of Tim-3 and PD-1 in CD8 T-cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14733–14738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009731107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sharma S, Sundararajan A, Suryawanshi A, Kumar N, Veiga-Parga T, Kuchroo VK, Thomas PG, Sangster MY, Rouse BT. T cell immunoglobulin and mucin protein-3 (Tim-3)/Galectin-9 interaction regulates influenza A virus-specific humoral and CD8 T-cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19001–19006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107087108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang X, Clark RA, Liu L, Wagers AJ, Fuhlbrigge RC, Kupper TS. Skin infection generates non-migratory memory CD8+ T(RM) cells providing global skin immunity. Nature. 2012;483:227–231. doi: 10.1038/nature10851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kupper TS. Old and new: recent innovations in vaccine biology and skin T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:829–834. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]