Abstract

Research has broadly established that emotional disturbances are associated with body image disturbances. This is the first study to examine links between facets of emotional awareness and peculiar body-related beliefs (PBB), or beliefs about an imagined or slight defect in one’s appearance or bodily functioning. In a sample of college students (n=216), we found that low emotional clarity (the extent to which the type and source of emotions are understood) was associated with higher PBB in both women and men, and the relation between emotional clarity and PBB was further moderated by attention to emotions (the extent to which emotions are attended to) and gender. Men with low attention to emotions and women with high attention to emotions both experienced higher levels of PBB if they also reported low levels of emotional clarity. This interactive effect was not attributable to shared variance with body mass index, neuroticism or affect intensity.

Keywords: Peculiar beliefs, Emotional awareness, Emotional clarity, Body image, Body dysmorphic disorder

Beliefs about an imagined or slight defect in appearance (e.g., deformed nose, facial scarring) or bodily functioning (e.g., excessive body odor, flatulence, sweating) might be thought of as peculiar because they are typically unfalsifiable (as opposed to patently false), deviate from the ordinary, and have less evidence and/or less convincing evidence to support their existence (Berenbaum, Kerns, & Raghavan, 2000). We therefore label these types of beliefs “Peculiar Body-Related Beliefs” (PBB). The PBB construct overlaps with DSM-IV criterion A for body dysmorphic disorder, as beliefs about an imagined or slight defect in appearance are one of several core features of body dysmorphic disorder (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). PBB are also common in other disorders characterized by body image disturbances, such as bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa (APA, 2000). At their extreme, these types of beliefs can be delusional in nature, and therefore indicative of a psychotic variant of body dysmorphic disorder (e.g., Phillips, Menard, Pagan, Fay & Stout, 2006). As these types of beliefs are common to a range of disorders characterized by body image disturbances, and can be quite severe at their extreme it is critical to gain an understanding of the factors that contribute to their formation and maintenance.

A substantial body of research has shown that various types of emotion disturbances are broadly associated with mental disorders characterized by body image disturbances (see Manjrekar & Berenbaum, in press). However, this research has generally been limited to emotional disturbances characterized by elevated levels of unpleasant affect and difficulties recognizing and processing emotional stimuli.

Another type of emotion disturbance that has received far less attention in this literature concerns the two dimensions that underlie emotional awareness, emotional clarity and attention to emotions (Coffey, Berenbaum, & Kerns, 2003). Attention to emotions refers to the extent to which a person actively attends to and reflects upon his/her affective experience, including the experience of emotions and moods, and uses this information to guide cognition and behavior. Emotional clarity refers to the extent to which a person can identify, discriminate between (e.g., anger versus fear), and understand their own feelings. Emotional clarity and attention to emotions are independent underlying dimensions of constructs such as alexithymia, emotional intelligence, and mood awareness (Coffey et al., 2003). Thus, emotional clarity and attention to emotions are commonly measured using items from related subscales of questionnaires that assess these constructs, such as the difficulty identifying emotions subscale (i.e., to measure emotional clarity) and the externally oriented thinking subscale (to measure attention to emotions) from the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (Bagby, Parker & Taylor, 1994),

Theory and basic research on emotion strongly support a potential link between PBB and emotional awareness. Emotions are considered by many theorists to be adaptive and directly affect cognitive processes, such as belief formation and change (Boden & Berenbaum, 2010). Empirical research supports this hypothesis, for example, by demonstrating that experimentally induced changes in affect arousal, valence, and/or type influences belief content and/or conviction (e.g., Boden & Berenbaum, 2007; Forgas, 1994; Miranda, Gross, Persons & Hahn, 1998). Therefore, one might reasonably expect that, like heuristics, emotions can serve as simple, efficient rules that help guide the formation and evolution of beliefs. When emotions provide useful and/or valid information, they are likely associated with adaptive and accurate beliefs. Accordingly, when emotions fail to provide useful and/or valid information, they might lead to maladaptive, inaccurate beliefs (e.g., Berenbaum, Boden, & Baker, 2009). Emotions are less likely to provide useful or valid information when emotional clarity is low (Clore, Gasper & Garvin, 2001). In such cases, beliefs may function to make sense of emotional arousal whose type and source is difficult to identify and understand due to low emotional clarity (e.g., Boden & Berenbaum, 2007).

The effect of emotional clarity on psychological outcomes, including beliefs, is in many cases moderated by attention to emotions (e.g., Berenbaum et al., 2009; Manjrekar & Berenbaum, in press), such that particular patterns of emotional clarity and attention to emotions are associated with positive or negative outcomes. In terms of psychopathology, two alternative patterns appear to be especially pernicious. The first pattern, labeled “overwhelmed”, consists of high attention to emotions and low emotional clarity. Previous research has found that individuals displaying this pattern attempt to avoid emotional experiences and information, even though they might involuntarily attend to it (Gohm, 2003; Kerns & Berenbaum, 2010). This pattern has also been found to be associated with a range of psychopathology, including a dimension of schizotypy that includes odd/peculiar beliefs (Kerns, 2005). The second pattern, labeled “cool”, consists of low attention to emotions and low emotional clarity. Previous research has demonstrated that this pattern is associated with psychopathology, such as suspicious beliefs (Boden & Berenbaum, 2007). We hypothesize that both emotionally overwhelmed and emotionally cool individuals are prone to develop psychopathological beliefs because they do not have access to valid or accurate emotional information that would help them to form accurate and adaptive beliefs. In both cases, because of low emotional clarity, information about emotions is often likely to be invalid or inaccurate. Even when information about emotions is valid and accurate, and thus useful in guiding belief formation, emotionally overwhelmed individuals may actively avoid this information, and emotionally cool individuals may not be cued to attend to this information. Research has suggested that the emotionally overwhelmed pattern may be especially relevant to and found among women, whereas the emotionally cool pattern may be especially relevant to and found among men (Gohm, 2003). These findings raise the possibility that psychopathological beliefs are associated with the emotionally overwhelmed pattern in women, and with the emotionally cool pattern in men.

Three studies have investigated links between emotional awareness and attitudes associated with body image disturbances (De Berardis et al., 2007; De Berardis et al., 2009; Manjrekar & Berenbaum, in press), though no studies have specifically examined relations between emotional awareness and PBB. Two studies (De Berardis et al., 2007; De Berardis et al., 2009) investigated relations between attitudes related to body image (i.e., body satisfaction) and alexithymia. In both studies, which included female college students, lower levels of emotional clarity were associated with higher levels of body dissatisfaction; in contrast, externally oriented thinking (which has been found to be inversely associated with attention to emotion; Coffey et al., 2003) was not associated with body dissatisfaction. Building upon these studies, Manjrekar and Berenbaum (in press) found that lower emotional clarity, but not attention to emotions, was associated with less body satisfaction (even after removing shared variance with BMI) in a sample of female college students. It was also found that an interaction between emotional clarity, attention to emotions, and negative affect significantly improved the ability to predict body satisfaction. Here, among individuals high in negative affect, attention to emotions moderated the link between emotional clarity and body satisfaction, such that higher levels of emotional clarity were associated with higher levels of body satisfaction except in participants showing high attention to emotions.

Despite strong theoretical links and supporting empirical research, previous research has not investigated the association between emotional awareness and PBB. Furthermore, the few studies that have investigated emotional awareness and attitudes related to body image disturbances are limited in that they included only female samples. Yet, there may be important gender differences in the relations between emotional awareness and PBB since, compared to men, women may (a) have more negative attitudes toward their bodies (Muth & Cash, 1997), and (b) attend more to their physical appearance (Muth & Cash, 1997).

In the current research we investigated the relations between emotional awareness and PBB in both male and female college students. Consistent with previous research (De Berardis et al., 2007; De Berardis et al., 2009; Manjrekar & Berenbaum, in press; Muth & Cash, 1997) we hypothesized that: (a) women would report higher levels of PBB; (b) lower levels of emotional clarity would be associated with higher levels of PBB in men and women; and (c) the relation between emotional clarity and PBB would be further moderated by attention to emotions and gender. In regard to the latter hypothesis, consistent with previous research (e. g., Gohm, 2003; Kerns, 2005), we hypothesized that women reporting an emotionally overwhelmed pattern of emotional awareness (low levels of emotional clarity and high levels of attention to emotions) would report the highest levels of PBB. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Boden & Berenbaum, 2007; Gohm, 2003), we also hypothesized that men reporting an emotionally cool pattern of emotional awareness (low levels of emotional clarity and low levels of attention to emotions) would report the highest levels of PBB. Lastly, we hypothesized that the interaction would remain significant after adjusting for variance shared with factors that might explain the association between emotional awareness and PBB. These factors included BMI, which is broadly associated with body image disturbances, and dispositional tendencies to experience negative affect (i.e., neuroticism; Laroi, Van der Linden, DeFruyt, van Os, & Aleman, 2006) and intense emotions (i.e., affect intensity). Increased neuroticism and affect intensity are potent emotional risk factors for the development of a range of psychopathology. We adjusted for these factors to provide evidence that significant associations were attributable to disturbances in emotional awareness, specifically, and not broad emotional risk factors that predispose people to experience a variety of emotional disturbances and types of psychopathology.

Methods

Participants

A convenience sample consisting of two hundred and sixteen participants (51% female) from a large midwestern university completed the measures included in this research as part of a larger study for course credit or monetary compensation. Eligibility criteria for the study were limited to being at least 18-years of age and enrolled as a student at the university. Ages of participants ranged from 17 to 28 years (M = 19.8, SD = 1.5). Most (58.3%) of the participants were European-American, followed by Asian/Asian-American (24.5%), Hispanic/Latino/a (9.3%), African-American (5.1%), and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (1.4%). The BMI of participants was obtained by directly measuring height and weight, and ranged from 15.6 to 43.4 (M = 23.0, SD = 4.2).

Procedures

Participants enrolled themselves in the study after reading a web-based electronic advertisement stating that the study was intended to investigate relations between a participant’s physical health, emotions, personality traits, memory, and information processing abilities. This advertisement was distributed to students in psychology courses at the university. All participants provided written informed consent. Groups of participants completed self-report measures of emotional arousal, emotional awareness, and peculiar beliefs in two study sessions occurring on separate days. The ordering of measures was counter-balanced across participants. The Institutional Reviewer Board of the university at which this research was conducted approved all study procedures.

Measures

Peculiar body-related beliefs (PBB)

PBB were measured using a modified version of the Dysmorphic Concerns Questionnaire (DCQ; Oosthuizen, Lambert, & Castle, 1998). We modified the original scale, which is composed of seven items that assess dysmorphic beliefs about physical appearance, in two ways. First, in an attempt to measure a broader range of PBB, we added 5 items that were developed by modifying the wording of existing items (e.g., changing “appearance” to “bodily functioning”). These five items were: (1) “Are you concerned about some aspect of your bodily functioning”, (2) “Do you spend time worrying about your bodily functioning”, (3) “Have you considered going to see a physician about an aspect of your bodily functioning”, (4) “Do you believe that something is wrong with your bodily functioning despite being told by others (e.g., doctor) that that there is nothing wrong”, and (5) “Do you spend time covering up or hiding aspects of your bodily functioning.” Two additional items on the original DCQ that are also included in our modified DCQ assess whether the respondent considers his/her body to be malfunctional, malformed, or misshapen in some way. Second, to make it consistent with the scales measuring emotional clarity and attention to emotions, we changed the response options from a 4-point scale to a 5-point scale (1=Not at all; 5 = Extremely).

The original version of the DCQ has excellent psychometric properties and reasonable evidence of convergent and discriminant validity. Since we added items and changed the scoring of the DCQ, in this sample we also examined its convergent validity with theoretically related constructs measured using a well-validated measure of body image (Multidimensional Body Self Relations Questionnaire [MBSRQ]; Brown, Cash, & Mikulka, 1990). The new DCQ was associated in expected directions with MBSRQ subscale assessing appearance orientation (r = .49, p < .01), body satisfaction (r = −.56, p < .01), preoccupation with being overweight (r = .57, p < .01), and appearance evaluation (r = −.52; p < .01). The mean score for dysmorphic body beliefs was 2.2 (SD = 0.8, Range = 1.0–4.8), and internal reliability (Cronbach’s α) was .90.

Emotional clarity & attention to emotions

Emotional clarity and attention to emotions were measured by selected items from well-validated scales of emotional awareness that were chosen based on the recommendations of Palmieri and colleagues (2009). Attention to emotions (attention) was measured by 10 items (e.g., “I don’t pay much attention to my feelings”) from the attention to emotions subscale of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS; Salovey et al., 1995) and externally oriented thinking subscale of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS; Bagby et al., 1994). Clarity of emotions was measured using 13 items (e.g., “I am usually very clear about my feelings”) from the clarity subscale of the TMMS and identification subscale of the TAS. See Palmieri and colleagues (2009) for a complete list of items. Participants indicated their responses using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Items were scored so that higher scores represented greater emotional clarity and attention to emotions. The constructs of emotional clarity and attention to emotions have been found to have reasonable evidence of convergent and discriminant validity, and to be meaningfully associated with a variety of psychological constructs (Bagby et al., 1994; Salovey et al., 1995). The mean score for attention to emotions was 3.9 (SD = 0.6, Range = 1.8–5.0), and internal reliability (Cronbach’s α) was .83. The mean score for emotional clarity was 3.8 (SD = 0.7, Range = 1.3–5.0), and internal reliability (Cronbach’s α) was .89.

Affect intensity

Trait levels of affect intensity were measured using the Affect Intensity Measure (AIM; Larsen, Diener & Emmons, 1986). Participants responded to 40-items (e.g., “My emotions tend to be more intense than those of most people”) using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = Never; 6 = always). The AIM has been shown to have good internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and good discriminant validity (Larsen et al., 1986). The mean score for affect intensity was 3.8 (SD = 0.5, Range = 2.3 – 5.2), and internal reliability (Cronbach’s α) was .90.

Neuroticism

Neuroticism was measured using the 10-item subscale of the 50-item version of the International Personality Item Pool (Goldberg, 1999). Items (e.g., “I am easily disturbed”) are answered using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Very inaccurate; 5 = Very accurate). Items were scored so that high scores reflected higher levels of neuroticism. The scale has been found to have good psychometric properties and reasonable evidence of convergent and discriminant validity (Goldberg, 1999). The mean score for neuroticism was 3.2 (SD = 0.7, Range = 1.5 – 4.8), and internal reliability (Cronbach’s α) was .87.

Data Analysis

We began by examining gender differences in PBB, attention to emotions, and emotional clarity by conducting independent sample t-tests; effect sizes were computed using Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988).

Next, we examined the associations between emotional awareness and PBB by computing partial correlations. As BMI scores were significantly associated with PBB in women (r = .23, p < .01) and men (r = .33, p < .01), we adjusted for shared variance with BMI to ensure that associations were not attributable to participant’s weight/height. We note that results were similar whether or not we removed shared variance with BMI. Since we found gender differences in PBB we computed partial correlations separately for men and women.

We then conducted a hierarchical regressions to investigate whether the different facets of emotional awareness were interactively associated with PBB. Given existing gender differences in predictor and criterion variables, we explored whether a three-way interaction between attention to emotions, emotional clarity and gender predicted PBB. In Step 1, we entered gender, and centered attention to emotions and emotional clarity scores. In Step 2, we entered all two-way interactions between variables. In Step 3, we entered the three-way interaction. We ran an additional regression analysis in which we accounted for shared variance with affect intensity, neuroticisim and BMI by including these variables in Step 1. To further explore this interaction, we conducted simple slope analyses (Aiken & West, 1991) and calculated simple slopes using unstandardized beta weights and 1.0 and −1.0 standard deviation values for trait source awareness (Cohen & Cohen, 1983).

Results

In support of our first hypothesis, we found that women reported significantly higher levels of PBB (t (214) = 3.6, p < .01; Cohen’s d = .48) than did men. In addition, women reported higher levels of attention to emotions than did men (t (214) = 3.9, p < .01; Cohen’s d = .53), and similar levels of clarity of emotions (t (214) = 1.0, ns; Cohen’s d = .14).

In support of our second hypothesis, attention to emotions was not associated with PBB for men or women, whereas emotional clarity was negatively associated with PBB for both men and women (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Zero-order Correlations Removing Shared Variance with BMI for Men (above diagonal) and Women (below diagonal).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dysmorphic Body Beliefs | −.07 | −.29** | .14 | .31** | |

| 2. Attention to Emotions | .09 | .14 | .32** | .01 | |

| 3. Emotional Clarity | −.27** | .35** | −.24* | −.59** | |

| 4. Affect Intensity | .15 | .34** | .06 | .27** | |

| 5. Neuroticism | .45** | .04 | −.38** | .48** |

p < .05;

p < .01.

In terms of investigating our third hypothesis, on Step 1 of the hierarchical regression analysis, gender, attention to emotions and emotional clarity together significantly predicted PBB (see Table 2). Emotional clarity and gender were significant predictors of PBB when accounting for each other and attention to emotions. Together, all two-way interactions on Step 2 significantly improved the prediction of PBB. The two-way interaction of attention to emotions by gender, but not attention to emotions by emotional clarity or emotional clarity by gender, was a significant predictor of PBB when accounting for shared variance with all two-way interactions and individual predictors. The addition of the three-way interaction between emotional clarity, attention to emotions, and gender significantly improved the prediction of PBB on Step 3. Furthermore, after accounting for shared variance with affect intensity, neuroticism and BMI, this three-way interaction continued to predict PBB.

Table 2.

Results of A Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analysis Predicting Peculiar Body-Related Beliefs.

| Step | Variables | β | R2 | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | .13** | .13** | ||

| Gender | −.21** | |||

| Attention to Emotions | .04 | |||

| Emotional Clarity | −.27** | |||

|

| ||||

| 2 | .04* | .16** | ||

| Gender X Attention to Emotions | −.26* | |||

| Gender X Emotional Clarity | .08 | |||

| Attention to Emotions X Emotional Clarity | .12 | |||

|

| ||||

| 3 | .03* | .19** | ||

| Gender X Attention to Emotions X Emotional Clarity | .29* | |||

p < .05;

p < .01.

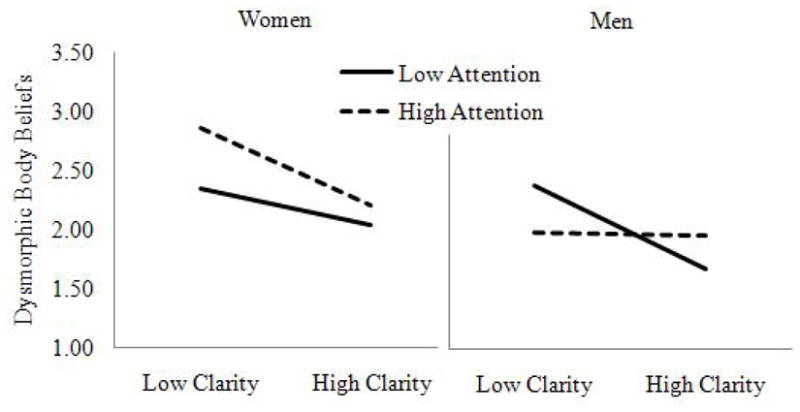

Simple slope analyses revealed that the relation between clarity and PBB was significant among men with low attention to emotions (β = −.44, p < .01) and women with high attention to emotions (β = −.41, p < .01), but not among men with high attention to emotions (β = −.01, ns) or women with low attention to emotions (β = −.20, ns). As shown in Figure 1, consistent with our hypotheses, men reporting an emotionally cool pattern of emotional awareness and women reporting an emotionally overwhelmed pattern of emotional awareness reported the highest levels of PBB.

Figure 1.

The Three-Way Interaction of Gender x Attention to Emotions x Emotional Clarity Predicting Dysmorphic Body Beliefs.

In summary, these results demonstrate that women report significantly higher PBB than men, and PBB are associated with low emotional clarity in both women and men. Furthermore, this association is further moderated by attention to emotions and gender, and this interaction is not attributable to BMI, or dispositional tendencies to experience negative affect or to experience intense emotions. Women report higher levels of PBB if they also report high attention to emotions, and women reporting an emotionally overwhelmed pattern also report the highest levels of PBB. Men with low emotional clarity report higher levels of PBB if they also report low attention to emotions, and men reporting an emotionally cool pattern also report the highest levels of PBB.

Discussion

The current study is the first to explore the relation between emotional awareness and body image disturbances related to PBB. Not surprisingly, we found that low emotional clarity was associated with greater PBB. Emotions have been shown to directly influence beliefs, possibly by serving as simple, efficient rules that help guide belief formation and change (see Boden & Berenbaum, 2010). In this manner, emotions serve a function similar to heuristics (Gilovich, Griffing & Kahneman, 2002), and provide a basis for judging the veracity of competing explanations for experience, one of which may eventually become more convincing and therefore, belief-like. However, emotions are less likely to provide useful or valid information when emotional clarity is low (e.g., Berenbaum et al., 2009). Therefore, emotions may contribute to inaccurate, maladaptive beliefs such as PBB. These beliefs may potentially function to explain or make sense of emotional arousal whose type and source is difficult to identify and understand because of low emotional clarity. Our data suggest that PBB may serve this type of explanatory function in both men and women. This hypothesis is further supported by research demonstrating that unexplained emotional arousal is experienced as unpleasant, and people are motivated to understand such arousal by finding an adequate explanation for its cause (Zimbardo, LaBerge & Butler, 1993; also see Wilson & Gilbert, 2008).

Consistent with previous research (e.g., Manjrekar & Berenbaum, in press; Berenbaum et al., 2009), our data show that attention to emotions was not significantly associated with PBB at the zero-order level. However, attention to emotions did moderate the interactive effect of clarity and gender on PBB. Linking and extending previous research (Boden & Berenbaum, 2007; Gohm, 2003; Kerns, 2005), we found that women reporting an emotionally overwhelmed pattern also reported the highest levels of PBB, and men reporting an emotionally cool pattern also reported the highest levels of PBB. We hypothesize that emotionally overwhelmed women and emotionally cool men did not use accurate or valid information about their emotions to guide formation about beliefs regarding their bodies, thus leading to maladaptive PBB. Besides not having such information because of low emotional clarity, emotionally overwhelmed women may have actively avoided emotional information (because of high attention to emotions), and emotionally cool men may not have been cued to attend to emotional information (because of low attention to emotions).

We note four primary limitations to the current study. First, we were limited to measuring emotional awareness and PBB through self-report questionnaires. Although it is difficult to measure these constructs other than by self-report (e.g., outside observers’ inferences regarding another’s emotions will necessarily be limited by idiosyncrasies in their own emotional experiences), future research might address this limitations by using: (a) a combination of self-report and idiographic behavioral assessments of emotional clarity (e.g., degree of concordance between individuals’ self-reports of what they were feeling and their facial expressions); (b) performance-based measures of attention to emotions (e.g., emotional stroop task); and (c) structured clinical interviews that include assessments of PBB. Doing so would also address a related limitation concerning the absence of strong psychometric data on our modified DCQ. A third limitation is the use of a convenience sample, which may limit the generalizability of results to populations with more severe PBB. A final limitation concerns the cross-sectional nature of the study, which restricts our understanding of whether emotional awareness disturbances contribute to PBB and/or vice versa. Future research can address this limitation by using analog experiments, in which mood inductions are combined with emotional awareness manipulations to investigate causal relations between constructs (e.g., Boden & Berenbaum, 2007).

Our findings have two implications for research on psychosocial treatments for disorders characterized by PBB, such as body dysmorphic disorder (Farrell, Shafran, & Lee, 2006). First, research investigating psychosocial treatments characterized by PBB may benefit from investigating whether gender and emotional awareness moderate the effects of treatment. Second, based on our findings, we hypothesize that psychosocial treatments of these conditions will benefit from increasing emotional clarity in both men and women. Related studies can investigate whether increases in emotional clarity lead to corresponding reduced conviction in PBB, and related distress. Extending this research to severe PBB that are delusions may be especially important, as psychotic variants of body dysmporhpic disorder are associated with higher levels of dysfunction and symptomatology (e.g., Phillips et al., 2006), which may result in greater treatment resistance.

Acknowledgments

This research and preparation of this paper were supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH071969). This manuscript was based on Matthew Tyler Boden’s dissertation submitted to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. We would like to thank the following research assistants for their contributions to this research: Marian Wiley-Moore, Jessica Barkwill, Sandra Domico, Jennifer Ernst, Julie Feldman, Amanda Hester, Emily Kostner, Sandra Perez, Trang Pham, Steffen Olsen, Marius Zyman, Nicole Heller, Katie Johnson, Britt Anderson, and David Tang.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bagby M, Parker JDA, Taylor GJ. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale- I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1994;38:23–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum H, Boden MT, Baker JP. Emotional salience, emotional awareness, peculiar beliefs, and magical thinking. Emotion. 2009;9:97–205. doi: 10.1037/a0015395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum H, Kerns JG, Raghavan C. Anomalous experiences, peculiarity, and psychopathology. In: Cardena E, Lynn S, Krippner S, editors. The varieties of anomalous experience. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum H, Valera EM, Kerns JG. Psychological trauma and schizotypal symptoms. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2003;29:143–152. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, Berenbaum H. Emotional awareness, gender, and suspiciousness. Cognition & Emotion. 2007;21:268–280. doi: 10.1080/02699930600593412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, Berenbaum H. The bidirectional relations between affect and belief. Review of General Psychology. 2010;14:227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Cash TF, Mikulka PJ. Attitudinal body image assessment: Factor analysis of the Body Self-Relations Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1990;55:135–144. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clore GL, Gasper K, Garvin E. Affect as information. In: Forgas JP, editor. Handbook of affect and social cognition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 121–144. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey E, Berenbaum H, Kerns JG. The dimensions of emotional intelligence, alexithymia, and mood awareness: associations with personality and performance on an emotional Stroop task. Cognition and Emotion. 2003;17:671–679. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- De Berardis D, Carano A, Gambi F, Campanella D, Giannetti P, Ceci A, Ferro FM. Alexithymia and its relationships with body checking and body image in a non-clinical female sample. Eating Behaviors. 2007;8:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Berardis D, Serroni N, Campanella D, Cerano A, Gambi F, Valchera A, Pizzorno AM. Alexithymia and its relationships with dissociative experiences, body dissatisfaction and eating disturbances in a non-clinical female sample. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2009;33:471–479. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell C, Shafran R, Lee M. Empirically evaluated treatment for body image disturbance: A review. European Eating Disorders Review. 2006;14:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Forgas JP. Sad and guilty? Affective influences on the explanation of conflict in relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gilovich T, Griffin D, Kahneman D, editors. Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gohm CL. Mood regulation and emotional intelligence: Individual differences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:594–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. Personality Psychology. 1999;7:7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns JG. Positive schizotypy and emotional processing. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:392–401. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns JG, Berenbaum H. Affective processing in overwhelmed individuals: Strategic and task considerations. Cognition and Emotion. 2010;24:638–660. [Google Scholar]

- Laroi F, Van der Linden M, DeFruyt F, van Os J, Aleman A. Associations between delusion-proneness and personality structure in non-clinical participants: Comparison between young and elderly samples. Psychopathology. 2006;39:218–226. doi: 10.1159/000093922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, Diener E, Emmons RA. Affect intensity and reactions to daily life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:803–814. [Google Scholar]

- Manjrekar E, Berenbaum H. Exploring the utility of emotional awareness and negative affect in predicting body satisfaction and body distortion. Body Image. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.05.005. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Gross JJ, Persons JP, Hahn J. Mood matters: Negative mood induction activates dysfunctional attitudes in women vulnerable to depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1998;22:363–376. [Google Scholar]

- Muth JL, Cash TF. Body-image attitudes: What difference does gender make? Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1997;27:1438–1452. [Google Scholar]

- Oosthuizen P, Lambert T, Castle DJ. Dysmorphic concern: Prevalence and associations with clinical variables. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;32:129–132. doi: 10.3109/00048679809062719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri PA, Boden MT, Berenbaum H. Measuring clarity of and attention to emotions. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2009;91:560–567. doi: 10.1080/00223890903228539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Menard W, Pagan ME, Fay C, Stout RL. Delusional versus nondelusional body dysmorphic disorder: Clinical features and course of illness. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Mayer JD, Goldman S, Turvey C, Palfai T. Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In: Pennebaker JW, editor. Emotion, disclosure, and health. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 1995. pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TD, Gilbert DT. Explaining away: A model of affective adaptation. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:370–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimbardo PG, LaBerge S, Butler L. Psychophysiological consequences of unexplained arousal: A posthypnotic suggestion paradigm. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:466–473. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.3.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]