Abstract

A young male patient reported for evaluation of progressive easy fatigability, accompanied by a recent history of recurrent haemoptysis. His clinical examination was unremarkable except for evidence of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Routine investigations (haemogram, coagulogram, serological tests for connective tissue disorders and a sputum Ziehl Neelsen stain for acid-fast bacilli) were normal. Two-dimensional echocardiography suggested PAH (pulmonary artery systolic pressure—67 mm Hg), whereas the 64-slice spiral CT pulmonary angiogram showed a dilated main pulmonary artery along with bilateral arteriovenous malformations. Cardiac catheterisation performed subsequently confirmed the presence of PAH. On the basis of the above findings, a diagnosis of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) complicated with PAH was made, and the patient was started on oral sildenafil therapy to which he responded well. This rare complication of HHT, which requires a high degree of suspicion for diagnosis, is discussed.

Background

Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) or Rendu Osler Weber syndrome, a disorder characterised by mucocutaneous telangiectasias and arteriovenous malformations (AVM) of internal organs, was first described by Henri J L M Rendu in 1886,1 and subsequently, its pattern of inheritance (autosomal dominant) and clinical features were described by William Osler and Fredrick Weber.2 3 The prevalence of HHT in the general population is 1 in 10 000. It is slightly higher in some of the geographical locations of Northern Japan, France and the Netherlands.4 A clinical spectrum of HHT varies from asymptomatic and incidentally detected lesions, aesthetic problems due to facial telangiectasias to episodes of recurrent epistaxis and, in a few cases, catastrophic events due to AVM involving the lungs, liver and brain.4 A clinical diagnosis of HHT is based on Curaçao criteria, which require three out of four criteria (epistaxes, telangiectasia, visceral lesions and an appropriate family history) to be present to make a definite diagnosis. Diagnosis is suspect or possible if only two criteria are present and unlikely if only a single criterion is present.4 HHT, however, may be difficult to diagnose as many signs of disease are age-dependent and do not manifest until late in life, more so in patients with sporadic disease.4

The presence of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients with HHT is rare and should be considered after ruling out respiratory and valvular or congenital heart disorders.

Case presentation

A 23-year-old male student presented with progressive easy fatigability of 6 months’ duration, accompanied by a recent history of cough with expectoration of fresh and altered blood of 2 weeks’ duration. There was no history of fever, anorexia and weight loss. There was a history of epistaxis on three occasions for which he received symptomatic therapy. There was neither any history of gastrointestinal bleeding or neurological symptoms nor any history of ingestion of any medication (anorexic agents). There was no history to suggest HHT in any of the family members. Clinical examination revealed normal vital parameters, no clubbing or cyanosis. His oxygen saturation was 90% on room air. There were coarse crepitations in the left infrascapular region and signs of PAH that were evident on cardiovascular examination. There was no evidence of mucocutanoeus telangiectasias or organomegaly.

Investigations

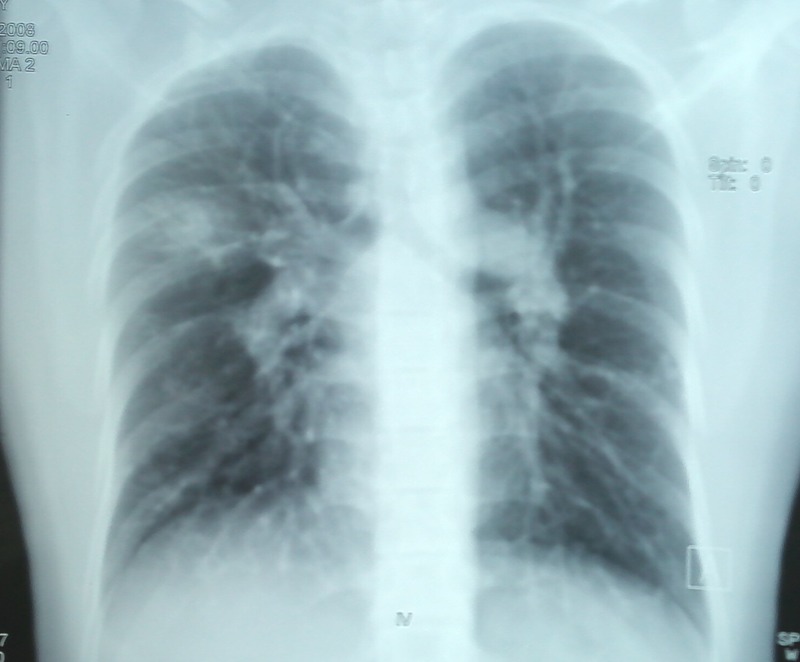

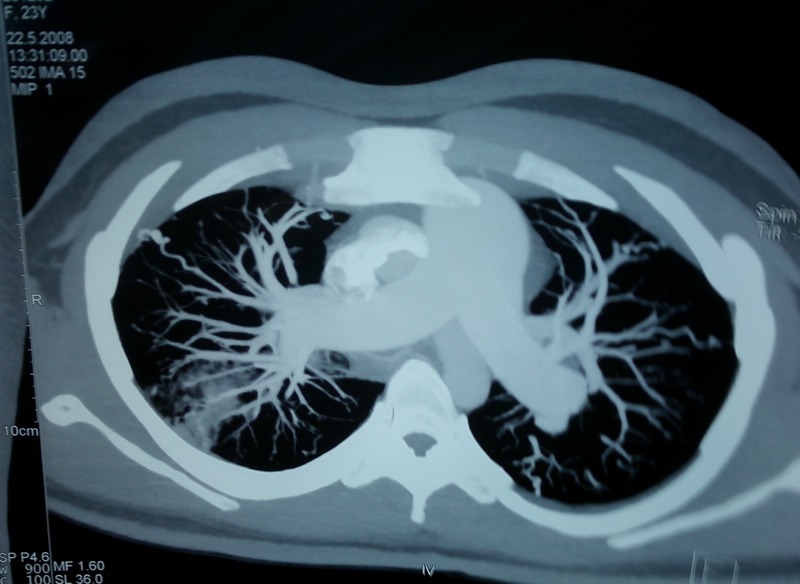

Routine investigations revealed normal haematological, biochemical and coagulation parameters. A chest radiograph showed patchy consolidation in the right upper zone in addition to the features of PAH (figure 1). The sputum Ziehl Neelsen stain was negative for acid-fast bacilli and the tuberculin test was negative. Fibreoptic bronchoscopy showed a normal trachea-bronchial tree. Bronchoalveolar lavage yielded mildly haemorrhagic fluid which was negative for AFB, fungal and malignant cytology. Serological tests for HIV, connective tissue disorders and systemic vasculitis were negative. Two-dimensional echocardiography showed a dilated right ventricle and right atrium and moderate tricuspid regurgitation with moderate PAH (pulmonary artery systolic pressure—67 mm Hg). piral CT angiography showed a dilated main pulmonary artery due to PAH and bilateral numerous pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) in the upper and lower lobes with an area of ground glass opacity due to pulmonary haemorrhage in the right lower lobe (figures 2–4). Ultrasonography of the abdomen, gastro-duodenoscopy and MRI brain done did not reveal any other AV malformations. Cardiac catheterisation indicated a mean pulmonary artery pressure of 54 mm Hg (72/40/54 mm Hg) and increased pulmonary vascular resistance (5.6 Wood units), with normal pulmonary capillary pressure (12 mm Hg) and an elevated cardiac index (5.5 l/min/m2). Screening of family members for AVM was negative. Genetic mutation analysis was not performed in this case due to financial constraints.

Figure 1.

Chest radiograph showing patchy alveolar opacities right upper zone and signs of pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Figure 2.

CT scan of the chest showing area of ground glass opacity in the right upper lobe with multiple pulmonary arteriovenous malformations.

Figure 3.

Contrast CT scan of the chest showing a dilated pulmonary artery due to pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Figure 4.

Spiral CT sagittal reconstruction images showing right upper lobe consolidation and bilateral pulmonary arteriovenous malformations in the lower lobes.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of haemoptysis in a young male with signs of pulmonary hypertension includes cardiac diseases such as mitral valve disease, congenital heart diseases, connective tissue diseases and pulmonary hypertension due to respiratory diseases such as bronchiectasis or cystic fibrosis.

Treatment

After careful analysis of all clinical, cardiac catheterisation and imaging data, a diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension associated with HTT was suggested. In view of multiple PAVM, interventional therapy with embolisation (coil, PVA particles and gel foam) was not feasible. The patient was treated with diuretics and 5-phosphodiesterase inhibitors sildenafil, the dosage of which was gradually increased from 25 mg three times a day to 75 mg three times a day.

Outcome and follow-up

The New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class of the patient improved on therapy from class III to class II over 2 months after initiation of therapy. There has been no recurrence of haemoptysis. Patient has been followed up closely and has not shown any deterioration in the clinical parameters (features of right heart failure), functional capacity (NYHA class/6 min walk distance) and haemodynamic parameters (right heart catheterisation) over the past 3 years.

Discussion

PAH is a rare manifestation of HHT noted in <1% of cases.5 It is listed in group 1 of the WHO clinical classification along with other heritable disorders of PAH.6 The diagnosis of PAH was established using right heart catheterisation, which is considered to be the diagnostic gold standard for the diagnosis of PAH. The pathogenetic mechanisms of PAH in patients with HHT could be a complex interplay of increased cardiac output and signalling abnormality involving transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) pathways.5 7 8 There is abnormal vascular proliferation and angiogenesis following mutation of activin receptor-like kinase 1 or endoglin genes which code for cell surface receptors proteins of TGF-β.5 7 8 9 TGF-β has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of primary pulmonary hypertension (PPH).9 There is no evidence of targeted therapy for this subgroup of patients. While prostanoids are known to increase risk of haemorrhagic complications,10 a combination of sildenafil and bosentan has been tried in some studies10–13 with beneficial effects. There is no role of vaso-occlusion of PAVMs as it is considered that high-flow and low-resistance PAVMs may contribute to decreased pulmonary artery pressure. There is sparse clinical experience in patients of HHT with PAH as no long-term studies are available in these patients. However, these patients, like the patients with PPH, require close follow-up to monitor the course of the disease. As per the guidelines provided by the European Society of Cardiology/European Respiratory Society, predictors of better prognosis are slow rate of progression of symptoms, absence of features of right heart failure, 6 min walk distance (6 MWD)> 500 m, absence of pericardial effusion and on haemodynamic monitoring a right atrial pressure of <8 mm Hg and cardiac index ≥2.5 l/min/m2,14 whereas the predictors of poor prognosis are rapid rate of progression of symptoms, presence of features of right heart failure, 6MWD<300 m, presence of pericardial effusion and on haemodynamic monitoring a right atrial pressure of >15 mm Hg or cardiac index ≤2 l/min/m2.14

In the present case, there was no family history of HHT, and screening for AVM was negative in the family members, thus suggesting that the case was probably due to spontaneous mutation. However, genetic screening for the type of mutation was not performed due to financial constraints.

The present case demonstrated multiple bilateral PAVM, which are generally noted in 15–33% of cases of HHT.4 PAVM in HHT are usually bilateral and multiple and predominantly involve the lower lobes. PAVM may remain asymptomatic or present with complications like transient ischaemic attack (10%), cerebrovascular accidents (10–19%), cerebral abscess (5–19%) and rarely massive haemoptysis or haemothorax due to lack of filtration of septic emboli in pulmonary capillaries and probably coexisting abnormality in innate immunity.4 Haemoptysis in patients with HHT results from a rupture of the pulmonary AVM and can be recurrent, massive and life threatening.4 5 HHT should be suspected in a young patient with recurrent haemoptysis after ruling out pulmonary infections, bronchiectasis, connective tissue and cardiac disorders.

The rarity of this case lies in the presence of multiple bilateral PAVM concurrently with severe PAH in a patient of HHT. To the best of our knowledge, HHT with PAVM and severe PAH from the Indian subcontinent has not been reported in the English literature.

Learning points.

Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is associated with mucocutaneous telangiectasias and arteriovenous malformations (AVM) of internal organs.

The clinical spectrum of HHT is protean and includes asymptomatic lesions, facial telangiectasias, recurrent epistaxis and catastrophic events due to rupture of the AVM involving internal organs (lungs, liver and brain).

HHT should be suspected in a young patient with recurrent haemoptysis after ruling out pulmonary infections, bronchiectasis, connective tissue and cardiac disorders.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension complicating HHT is an extremely rare entity. It is seen in <1% cases and is associated with poor prognosis.

The pathogenesis and treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) in HHT is similar to primary pulmonary hypertension.

Treatment and prognosis of PAH is guided by periodic clinical examination, assessment of functional capacity and haemodynamic parameters of the patients.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Rendu H. Epistaxis repetees chez un sujet porteur de petits angiomes cutanes et muquez. Gaz Hôpitaux 1896;13:1322–3 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osler W. On a family form of recurring epistaxis, associated with multiple telangiectases of the skin and mucous membranes. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1901;12:333–7 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber F. Multiple hereditary developmental angiomata (telangiectases) of the skin and mucous membranes associated with recurring hemorrhages. Lancet 1907;2:160–2 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olitsky SE. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 2010;82:785–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faughnan ME, Granton JT, Young LH. The pulmonary vascular complications of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Eur Respir J 2009;33:1186–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonneau G, Robbins I, Beghetti M, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:S43–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raimondi A, Blanco I, Pomares X, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in a patient with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Arch Bronconeumol 2012. Jun 22 (Epub ahead of print) PMID: 22727716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigelsky CM, Jennings C, Lehtonen R, et al. BMPR2 mutation in a patient with pulmonary arterial hypertension and suspected hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Am J Med Genet A 2008;146A:2551–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayala E, Kudelko KT, Haddad F, et al. The intersection of genes and environment: development of pulmonary arterial hypertension in a patient with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia and stimulant exposure. Chest 2012;141:1598–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cottin V, Dupuis-Girod S, Lesca G, et al. Pulmonary vascular manifestations of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler disease). Respiration 2007;74:361–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reichenberger F, Wehner LE, Breithecker A, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in hereditary haemorrhagic teleangiectasia. Pneumologie 2009;63:669–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang SA, Jang SY, Ki CS, et al. Successful bosentan therapy for pulmonary hypertension associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Heart Vessels 2011;26:231–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Providência R, Mdo C Cachulo, Costa GV, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: rare cause of pulmonary hypertension. Arq Bras Cardiol 2010;94:e34–6, e94–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galiè N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2009;34:1219–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]