Abstract

AIDS is an increasingly common diagnosis seen by neurologists and neurosurgeons alike. Although the more common brain lesions associated with AIDS are due to central nervous system lymphomas, toxoplasma encephalitis or progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, relatively recent clinical evidence has shown that AIDS-independent cerebral tumours can arise as well, albeit less commonly. Previous incidents have been reported with HIV and AIDS patients presenting with cerebral astrocytomas. To our knowledge, there has never been a report in the literature of a brainstem anaplastic glioma occurring in an AIDS or HIV patient. We report a 55-year-old patient with HIV and brainstem anaplastic glioma. Its presentation, diagnostic difficulty, scans, histology and subsequent treatment are discussed. We also review the relevant literature on gliomas in HIV/AIDS patients.

Background

AIDS is a complex disease that presents with a torrent of related illnesses affecting various organs of the human body. The brain is no exception. It is estimated that over 50% of Americans suffering from AIDS brave neurological complications.1–3 Although the more common brain lesions associated with AIDS are due to the central nervous system (CNS) lymphomas, toxoplasma encephalitis or progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML),4 relatively recent clinical evidence has shown that AIDS-independent cerebral tumours5 can arise as well, albeit less commonly. Previous incidents have been reported with HIV and AIDS patients presenting with cerebral astrocytomas6 (table 1), with only one case of a brainstem glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) reported in Germany in 2002.7 To our knowledge, there has never been a report in the literature of a brainstem anaplastic glioma occurring in an AIDS or HIV patient. We report a patient with HIV and brainstem anaplastic glioma. Its presentation, diagnostic difficulty, scans, histology and subsequent treatment are discussed.

Table 1.

HIV/AIDS patients with glial tumours

| Author and Year | Country | Age(s) | Sex | Other factors | Diagnosis | Location | Presentation | Procedures | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corti et al (2004) | Argentina | 31 | F | – | Oligodendroglioma | R frontal lobe, insula | Generalized seizure, headache | MRI and biopsy; resection | >28 months |

| Chamberlain et al (1994) | USA | 32 | M | H | GBM | R temporal lobe | Seizure | CT and biopsy; resection | – |

| 37 | M | H | L frontal lobe | Seizure | CT and biopsy | – | |||

| 38 | M | H | R frontal lobe | Headache and right UE weakness | CT and biopsy | – | |||

| Gasnault et al (1988) | France | 19 | M | D | Malignant astrocytoma | R central sulcus | L seizure, L paresis | CT and biopsy; radiotherapy | 1 year |

| 43 | M | H | Pilocytic astrocytoma | L posterior hemisphere | R vision loss, R pyramidal signs | CT and biopsy | 10 days | ||

| Gongora-Rivera et al (2000) | Mexico | – | – | – | Oligodendroglioma | – | – | – | – |

| – | – | – | Anaplastic astrocytoma | – | – | – | – | ||

| Hall et al (2009) | UK | 33 | M | – | GBM | L frontal lobe | Grand mal seizure | MRI and biopsy; resection, radiotherapy | 13 months |

| 50 | F | – | GBM | R frontal lobe | Focal seizures | MRI and biopsy; resection | >2 years | ||

| 43 | M | – | GBM | R temporal lobe | Complex partial seizures | MRI and biopsy; resection, radiotherapy | 12 months | ||

| 42 | F | – | GBM | L basal ganglia | R side weakness | MRI and biopsy; resection | 2 months | ||

| Ho et al (1987) | USA | – | M | – | Cerebral astrocytoma | – | – | Biopsy | – |

| Ho et al (1991) | USA | 37 | M | H | Cerebral astrocytoma | – | Cytomegalovirus infection of the glioma | Biopsy | – |

| Kasantikul et al (1992) | Thailand | 32 | M | H | Cerebral astrocytoma | L parieto-occipital lobe | Headache, right hemiparesis | CT and biopsy | – |

| Moulignier et al (1994) | France | 30–48 | M | H | Cerebral astrocytoma | F lobe | Frontal syndrome | CT and biopsy | – |

| H | Cerebral astrocytoma | R. parietal lobe | General seizures | CT and biopsy | – | ||||

| H | Cerebral astrocytoma | L parieto-occipital lobe | General seizures | CT and biopsy | – | ||||

| D | GBM | Subthalamic | L. hemiparesis | CT and biopsy | – | ||||

| Neal et al (1996) | UK | 35 | M | H | Malignant astrocytoma | Frontal, occipital, and L. temporal lobe | Headache, vomiting, gait disturbance, R. vision loss, olfactory hallucination | MRI and biopsy | 2 months |

| Tacconi et al (1995) | UK | 22 | M | D | Cerebral astrocytoma | L. temporal lobe | Of the 4 patients, 2 had focal seizures, 1 with hemiparesis, 1 with headache | CT, MRI, and biopsy; radiotherapy | 20 months |

| 32 | M | H | Cerebral astrocytoma | L. frontal lobe | ^ | CT, MRI, and biopsy; radiotherapy | >10 months | ||

| 38 | M | H | Cerebral astrocytoma | R. frontal lobe | ^ | CT, MRI, and biopsy; radiotherapy | >6 months | ||

| 44 | M | H | Anaplastic astrocytoma | R. basal ganglia | ^ | CT, MRI, and biopsy; radiotherapy | 7 months | ||

| Vannemreddy et al (2000) | USA | 29 | M | – | GBM | Corpus callosum, F lobes | Headache and L side sensory impairment | CT, MRI, and biopsy; radiotherapy | 1 month |

| Waubant et al (1998) | France | – | – | – | Glioma | Cervical cord | – | – | – |

D, IV drug user; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; F, female; F. lobe: frontal lobe; H, homosexual; L. frontal lobe, left frontal lobe; L. parieto-occipital lobe, left parieto-occipital lobe; L. paresis, left paresis; L. seizure, left seizure; L. side sensory impairment, left side sensory impairment; L. temporal lobe, left temporal lobe; M, male; R. basal ganglia, right basal ganglia; R. frontal lobe, right frontal lobe; R. parietal lobe, right parietal lobe. ; R. pyramidal signs, right pyramidal signs; R. vision loss, right vision loss.

Case presentation

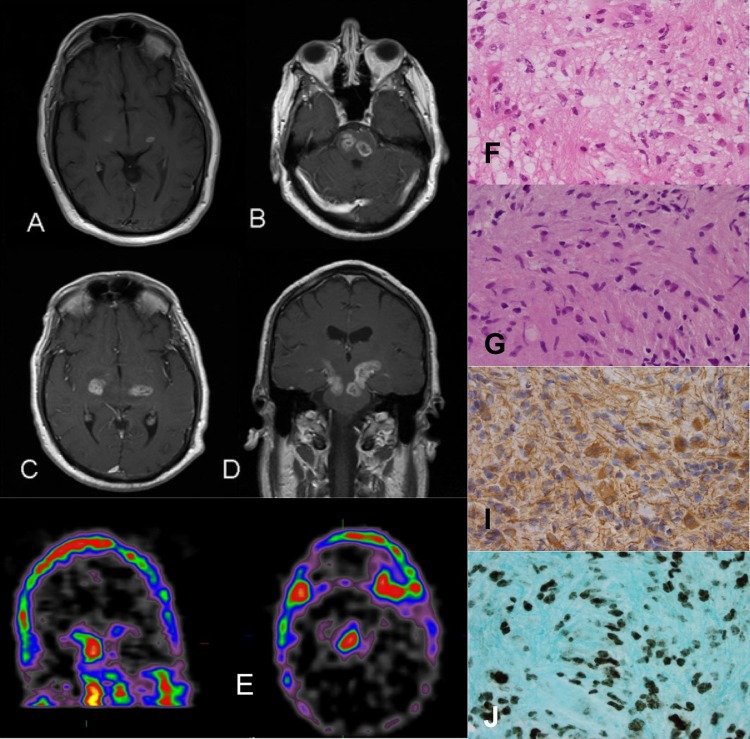

A 55-year-old Hispanic man with a history of HIV (diagnosed 3 years ago), diabetes and hypertension presented with left hemiparesis, numbness and pain in the left side of the body for one month. The CD-4 count at presentation was 423 cells/µl and he was on antiretroviral therapy. His initial MRI had revealed multiple brainstem lesions in an outside hospital, and he was thought to have an infection and treated for the same with antibiotics and discharged to rehabilitation (figure 1A). He presented to our hospital with a worsening left hemiparesis and ocular motion abnormalities despite adequate treatment for toxoplasmosis. A new MRI scan demonstrated worsening bilateral enhancing lesions involving the cerebral peduncles, midbrain and pons (figure 1B–D). Single photon emission tomography of the brain with thallium revealed a delayed increased uptake in the lesions in the midbrain/pons, with the right greater than the left (figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Initial MRI brain with contrast revealing enhancing lesions in bilateral cerebral peduncles (A). On follow-up MRI, the lesions increased in size. Axial images revealing enhancing lesion in the pons, bilaterally (B), bilateral cerebral peduncles (C) and extending from the upper pons to the lower part of the posterior limb of the internal capsule (along corticospinal tracts) on coronal sections (D). (E) Single photon emission tomography thallium of the brain revealed an abnormally increased delayed uptake associated with previously visualised enhancing lesions in the midbrain/pons and cerebral peduncles, with the right greater than the left. This finding is most commonly associated with lymphoma but is non-specific. (F) H&E ×40. Histology at the frozen section. (G) H&E ×40. The nuclei display a prominent pleomorphism with abnormal mitotic figures. (I) Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunohistochemistry ×40. Tumour cells were strongly reactive for GFAP, indicating glial origin. (J) Histopathology revealed an anaplastic glioma with atypical glial proliferation and strong Ki-67 immunoreactivity.

Lymphoma was felt to be the most likely diagnosis on clinical and radiological grounds. A stereotactic needle biopsy was performed for diagnostic purposes. Extensive non-invasive and less invasive workup, including serological and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing, were non-diagnostic. CSF cytology of the patient on steroids showed an atypical lymphoreticular process suspicious for lymphoma, but the follow-up flow cytometry and gene rearrangement studies did not confirm lymphoma. The CSF Epstein-Barr virus PCR was negative.

The medical oncology team consulted us for biopsy but would have proceeded with empiric chemotherapy for primary CNS lymphoma if the biopsy could not be safely performed. Owing to the deep and sensitive location of the lesion, a frame-based biopsy was performed without any complications. Histopathology revealed an anaplastic glioma with atypical glial proliferation and strong Ki-67 immunoreactivity (figure 1J). After the final diagnosis was made, the patient's family decided not to pursue active treatment and he was given palliative care.

Discussion

More than half of the HIV/AIDS patients may present with neurological problems. Many of these lesions are found to be toxoplasmosis, CNS lymphomas or PML. However, in the last 30 years or so, there have been several reports of gliomas in previously diagnosed HIV and AIDS patients. In the general population, the prevalence of brain tumours is 209 cases/100 000.8 The current literature has few reports on gliomas occurring in the HIV/AIDS patients, the majority being from European countries. Our review of several published reports between 1987 and 2009 revealed 26 cases of gliomas in patients with HIV/AIDS. Age at diagnosis in these previous cases ranged from 19 to 50 years (table 1). Most of the patients die from their gliomas within months to 2 years of diagnosis.

We have reported a case of an HIV patient with a biopsy-confirmed brainstem anaplastic glioma. In our search, we came across only one article of a brainstem GBM in Germany in 2002.7 To our knowledge, there are no other reports of brainstem gliomas in the literature (table 2).

Table 2.

HIV/AIDS patients with brainstem glioma

| Author and Year | Country | Age(s) | Sex | Other factors | Diagnosis | Location | Presentation | Procedures | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wolf et al (2002) | Germany | 31 | M | – | GBM | Brainstem | CN IX, X, XII functional difficulties | CT and biopsy | 64 days |

| Present study (2011) | USA | 55 | M | – | Anaplastic astrocytoma | Brainstem | L hemiparesis | CT and biopsy | >1 month |

CN, cranial nerve; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; L. hemiparesis, left hemiparesis; M, male.

M, male.

A pathological examination of the tissue revealed a population of tumour cells with increased cellular density, pleomorphism, nuclear hyperchromasia and mitotic activity infiltrating the normal brain parenchyma. Coagulative necrosis and microvascular proliferation were absent; the two findings are characteristic of glioblastoma. The tumour cells were strongly immunoreactive to glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and are indicators of glial origin. Additionally, the tumour cells demonstrated strong immunoreactivity towards Ki-67, an indication of their proliferative nature. Based on these morphological findings and its immunophenotype, the tumour was classified as an anaplastic astrocytoma.

Although the vast majority of brain lesions in the HIV and AIDS patients are infections or lymphomas, it is important to keep primary brain tumours like gliomas in the differential diagnosis. In our review of the literature, many of the HIV and AIDS patients were diagnosed with a brain tumour after presenting with neurological symptoms such as headaches, gait disturbances, nausea, vomiting, seizures, hemiparesis, visual loss and even olfactory hallucination (table 1). A spinal cord glioma has been known to occur in this patient population as well.9

The pathogenesis of brain tumours in the HIV and AIDS patients remains poorly understood. It is possible that brain tumours arise from the immune compromised states present in patients with HIV and AIDS. HIV is believed to enter the CNS by infecting macrophages via gp120 binding at the CCR5 and CXCR4 receptors.10 11 Some neurons and astrocytes are thought to share these receptors as well, which can result in their subsequent infection. This can disrupt chemokine and inflammatory signalling and alter neuronal and glial functions. HIV can also cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) by using tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Macrophages and astrocytes are known to communicate with each other through feedback loops. HIV infection can compromise this interaction. For example, HIV-infected macrophages increase the production of TNF-alpha and interleukin (IL)-1β, which can induce astrocytosis. Generally, it is known that neuronal cells are more vulnerable to HIV infection and astrocytes are rarely affected. Astrocytes may even provide partial protection to neuronal cells from HIV infection.10 But the rare instances where glial cells are affected may provide the breeding ground for an astrocytoma.12

Treatment of gliomas in AIDS patients should generally be on the same lines as in other patients, but their prognosis with respect to AIDS status should be kept in mind while deciding on the treatment strategy.13 A surgical resection is performed to remove the tumour, unless it is inoperable. Radiation therapy was found to prevent the growth of the tumours in two patients.14 Chemotherapy was found to increase a patient's life by 10 months.15 Most of the other patients with similar treatments died within months to a year of brain tumour diagnosis due to complications (ie, increased intracranial pressure, pulmonary embolism post biopsy, exacerbation of infection) or recurrence.

Glial tumours should be added to the differential in AIDS patients with brain lesions, especially if the lesions are unresponsive to toxoplasmosis treatment and lymphoma has been ruled out. Correct diagnosis in the early stages can prevent the patient from being subjected to inappropriate therapies and perhaps increase their time and quality of life. If technically feasible, a biopsy should always be done to confirm the diagnosis before starting empiric treatment.

Learning points.

Correct and timely diagnosis of brain lesions in AIDS patients can prevent the patient from being subjected to inappropriate therapies and may increase their quality of life.

Gliomas should be added to the differential diagnosis of these lesions if toxoplasmosis and lymphoma has been ruled out.

The treatment of gliomas in AIDS patients is similar to that in non-AIDS population and whenever feasible, a biopsy should be done to establish the diagnosis.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Neurological complications of aids fact sheet. NINDS 2006 http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/aids/detail_aids.htm (accessed 28 January 2013)

- 2.Gongora-Rivera F, Santos-Zambrano J, Moreno-Andrade T, et al. The clinical spectrum of neurological manifestations in AIDS patients in Mexico. Arch Med Res 2000;31:393–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neal JW, Llewelyn MB, Morrison HL, et al. A malignant astrocytoma in a patient with AIDS: a possible association between astrocytomas and HIV infection. J Infect 1996;33:159–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robbins SL, Kumar V, Cotran RS. Robbins and cotran pathologic basis of disease. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corti ME, Yampolsky C, Metta H, et al. Oligodendroglioma in a patient with AIDS: case report and review of the literature. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2004;46:195–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gasnault J, Roux FX, Vedrenne C. Cerebral astrocytoma in association with HIV infection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988;51:422–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolff R, Zimmermann M, Marquardt G, et al. Glioblastoma multiforme of the brain stem in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144:941–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heros RC. Randomized clinical trials. J Neurosurg 2011;114:277–8; discussion 78–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waubant E, Delisle MB, Bonafe A, et al. Cervical cord glioma in an HIV-positive patient. Eur Neurol 1998;39:58–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaul M, Zheng J, Okamoto S, et al. HIV-1 infection and AIDS: consequences for the central nervous system. Cell Death Differ 2005;12(Suppl 1):878–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasantikul V, Kaoroptham S, Hanvanich M. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome associated with cerebral astrocytoma. Clin Neuropathol 1992;11:25–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vannemreddy PS, Fowler M, Polin RS, et al. Glioblastoma multiforme in a case of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: investigation a possible oncogenic influence of human immunodeficiency virus on glial cells. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 2000;92:161–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moulignier A, Mikol J, Pialoux G, et al. Cerebral glial tumors and human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection. More than a coincidental association. Cancer 1994;74:686–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tacconi L, Stapleton S, Signorelli F, et al. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and cerebral astrocytoma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1996;98:149–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chamberlain MC. Gliomas in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Cancer 1994;74:1912–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]