Abstract

A 65-year-old gentleman with stage 5 chronic kidney disease developed an acute posterior circulation stroke, which was treated with intravenous thrombolytic therapy. This was complicated by a retroperitoneal haemorrhage. The patient made an excellent neurological recovery and was discharged to home, independently mobile, having been established on haemodialysis. This case highlights the challenges of managing acute ischaemic stroke in patients with advanced uraemia.

Background

It is well known that patients with advanced renal impairment are at a greater risk of stroke than the general population. Intravenous thrombolytic therapy has been shown to be an effective treatment for acute ischaemic stroke (AIS). The main complication of treatment is bleeding, which may be either intracranial or systemic.

There are conflicting reports on the use of thrombolysis for AIS in patients with renal impairment, and in particular there is a concern that there may be an increased risk of bleeding.

Our case highlights:

The clinical presentation of posterior circulation stroke can be similar to that of uraemic encephalopathy, and despite the potential increased risk of bleeding in advanced uraemia with the use of thrombolysis, a good outcome can be achieved.

Thrombolysis in this patient subgroup should not be automatically withheld, but each presentation considered on a case-by-case basis, with careful consideration of the risks involved.

Case presentation

A 65-year-old man with progressive chronic kidney disease (CKD), secondary to diabetic nephropathy presented to the regional nephrology centre with a 3 weeks history of nausea, itch, poor appetite and fluid overload unresponsive to oral diuretic therapy. He lived at home with his wife, was independent of activities of daily living and independently mobile. Initial blood results revealed: urea 30 mmol/l, creatine 479 umol/l, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 11 ml/min, Haemoglobin 9.2 g/dl, platelets 125×109/l and coagulation screen normal. There was no evidence of a pericardial rub or uraemic flap and he was cognitively intact.

His medical history included ischaemic heart disease, porcine mitral valve replacement, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. There was no known history of stroke or atrial fibrillation. Medication included aspirin 75 mg.

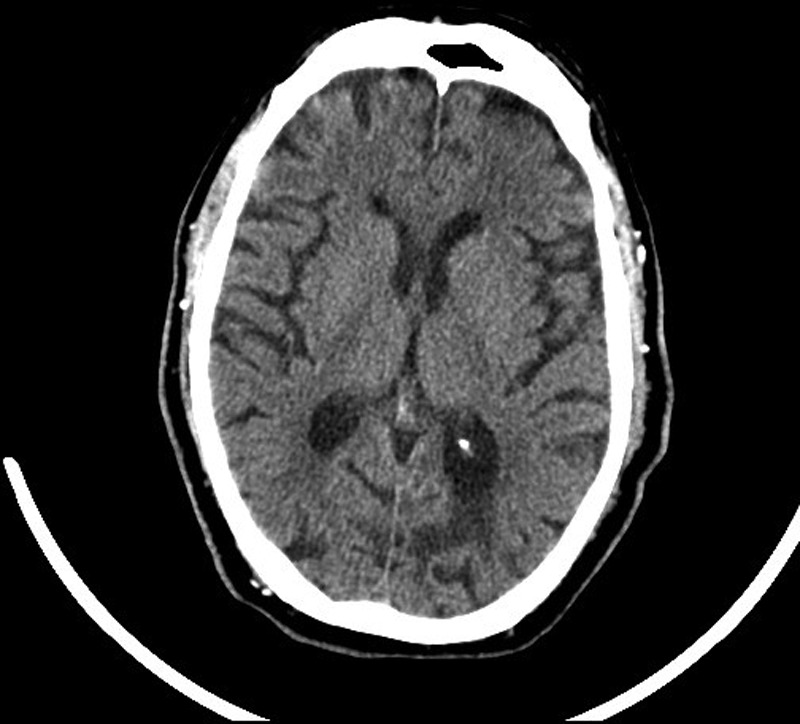

Forty-eight hours following admission, while talking with his wife, the patient suddenly became drowsy. His Glasgow Coma Scale score was recorded at 12/15 (E3, V4, M5). On examination, he had dysarthria, disconjugate eye movements, a right homonymous hemianopia, nystagmus on gaze to the right, bilateral limb weakness, a right up-going plantar and a flapping hand tremor. The initial National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 14. Capillary blood glucose was 6.4 mmol/l. ECG revealed normal sinus rhythm with first-degree heart block. An urgent CT of the brain was performed approximately 1 h following symptom onset (figure 1). This showed evidence of an old left occipital infarct and periventricular white matter ischaemic changes, but no evidence of intracranial haemorrhage (ICH).

Figure 1.

CT of the brain showing an old left occipital infarct, age related involutional change and chronic white matter ischaemia.

Treatment

The patient received intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (r-tPA) at 135 min after the onset of symptoms. There was some improvement in his condition and repeated NIHSS at 2 h was 11.

Twelve hours after treatment, the patient complained of pain and weakness in his right leg. Repeated blood tests revealed a drop in haemoglobin to 6.9 g/dl, platelets 112×109/l and coagulation screen as follows: PT 17.7s, APTT 27.3s, fibrinogen 5.23 g/l and a thrombin clotting time of 19.3s.

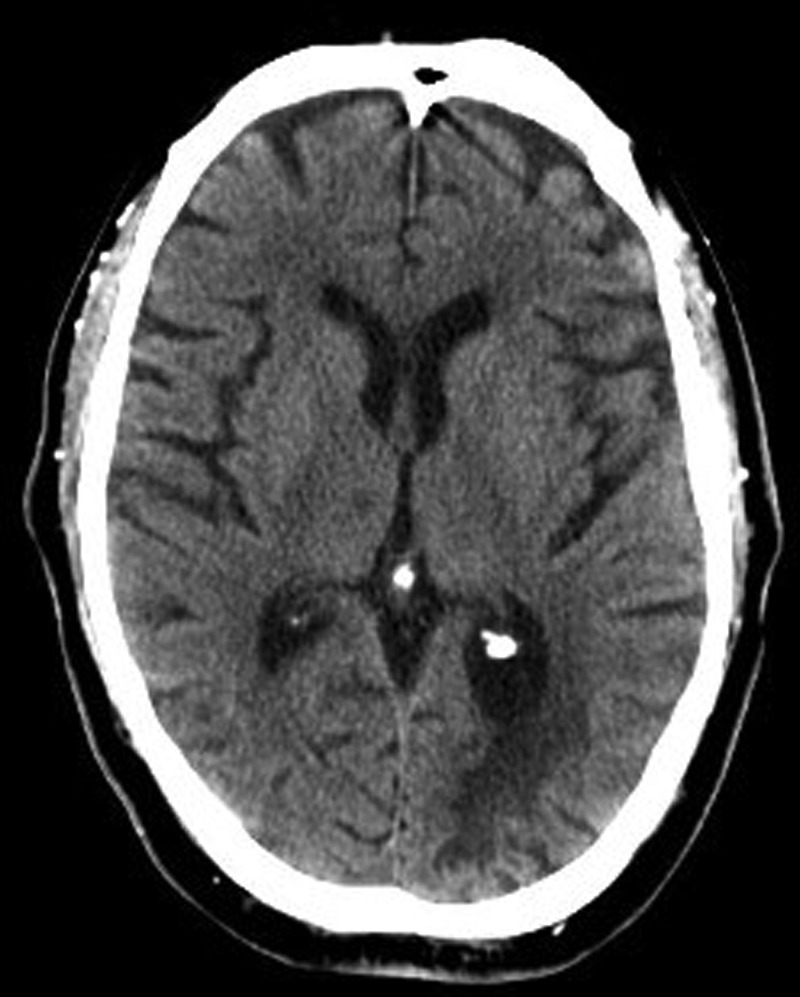

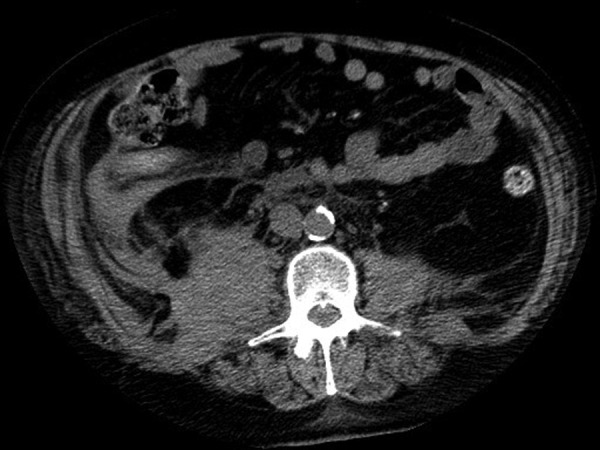

An urgent repeated CT of the brain (figure 2) was performed approximately 14 h following initial symptom onset, which revealed a small area of decreased attenuation in the region of the right thalamus which had not been present on the previous scan. CT of the abdomen (figure 3) was also performed which revealed swelling and enlargement in the region of the right psoas extending into the iliopsoas with associated stranding within the retroperitoneal fat, in keeping with a right-sided retroperitoneal haematoma.

Figure 2.

Repeated CT of the brain at approximately 14 h following the onset of symptoms at the same slice as the previous CT of the brain in figure 1, showing the decreased attenuation in the region of the right thalamus.

Figure 3.

CT of the abdomen showing the right sided retroperitoneal haematoma.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was haemodynamically stable; however, given the significant retroperitoneal haemorrhage and evidence of fibrinogen depletion, he was treated with cryoprecipitate and platelets after discussion with haematology. His neurological condition continued to improve and repeated NIHSS at 24 h was 7. He was subsequently started on haemodialysis therapy.

Cardiac imaging revealed mild aortic stenosis with an ejection fraction of 65% with no evidence of thrombus or vegetations. CT angiogram of aortic arch and carotid vessels revealed heavy calcified plaque disease at both the common carotid bifurcations as well as further disease, bilaterally at the ostium of the vertebral arteries. Carotid Doppler indicated very minimal stenosis bilaterally.

The patient was unsuitable for MRI of the brain due to the presence of a metal pellet in his left forearm on x-ray (figure 4).

Figure 4.

x-Ray of the left forearm showing the metal pellet.

The final diagnosis was a thalamic infarct, secondary to vertebral atheroma. He continued to improve with repeated NIHSS score of 5 at day 7.

The patient was subsequently discharged home following 5 weeks of rehabilitation, independently mobile.

Discussion

It is well established that CKD is associated with an increased risk of stroke.1 This phenomenon was initially observed in patients with end-stage renal disease who have a 4-fold to 10-fold greater stroke risk as compared to the general population.2 3

Patients with uraemia have an increased bleeding tendency associated with platelet dysfunction.4 Given with this, there are concerns about the use of tissue plasminogen activators (tPA) with regard to the appropriate management of patients with end stage renal disease presenting with AIS. Dialysis is thought to remove uraemic toxins and hence reduce the risk of uraemic bleeding; however, there are limited data on the efficacy of dialysis in actively bleeding uraemic patients.4 Of note, uraemia is not listed as a contraindication to thrombolysis in the standard guidelines.5

A recent survey on the expert opinion, on the use of thrombolysis for AIS in haemodialysis patients reported that although the majority of stroke experts favoured the use of tPA in this sub-group, only one-third had actually used it to treat AIS in patients on dialysis.6

A study by Lyrer et al7 of 196 patients, presented with AIS who were treated with thrombolysis, suggested that impaired renal function, defined as an eGFR <90 ml/min, was associated with poor outcomes and a trend towards symptomatic ICH. However, only two of the patients included in the analysis had an eGFR <30 ml/min and none of the patients were on dialysis.7

A subsequent review by Agrawal et al,8 which compared the use of thrombolysis in those with an eGFR >60 ml/min (n=54) and those with an eGFR <60 ml/min (n =20) suggested that the presence of an eGFR <60 ml/min was not found to be associated with increased ICH, poor functional outcome or death compared to those with an eGFR >60 ml/min. Furthermore, this study subdivided the groups, and included nine patients with an eGFR 45–60 ml/min, six patients with an eGFR 30–45 ml/min, two patients with an eGFR 15–30 ml/min and three patients with an eGFR <15 ml/min.8 The conclusions from this study are, however, limited due to the small number of patients with an eGFR <30 ml/min.

The largest and most recent observational study by Naganuma et al9 looked at the use of thrombolysis for AIS in 578 patients with and without renal impairment. They concluded that patients with impaired renal function, defined as an eGFR <60 ml/min on admission (n=186) were more likely to have early ICH and poor outcomes at 3 months. The study, however, did not provide a breakdown of eGFR subgroups. It is also important to note that patients who did not receive tPA were not included in this study, thus a comparison of outcome could not be made. Renal function was measured on admission and may not have been representative of CKD. Renal dysfunction was correlated with older age, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, prior ischaemic heart disease and prior use of antithrombotic agents.9 These factors have previously been looked at in the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study10 and were associated with symptomatic ICH or death at 3 months. Naganuma et al,9 therefore, also concluded that the association of renal dysfunction with outcome measures after multivariate analyses may be overestimated to some extent.

Thrombolytic therapy with intravenous tPA is an effective treatment of AIS.11 Data from observational studies give conflicting reports regarding the increased risk of ICH after thrombolysis for AIS in patients with uraemia. Until more robust data are obtained from randomised controlled trials or large databases, we would suggest appropriately selected patients with renal dysfunction, should not necessarily be excluded from the administration of intravenous tPA therapy for AIS.8

Learning points.

The bleeding risk in advanced uraemia may have contributed to this patient, developing the retroperitoneal bleed following thrombolysis.

There is conflicting evidence regarding the outcome of thrombolysis in AIS patients with renal dysfunction. This may be explained by confounding comorbidities for poor outcome.

Limited evidence exists in patients with an eGFR <15 ml/min, presenting with AIS and who receive protocol-driven thrombolytic therapy have in-hospital outcomes, similar to those without renal dysfunction.

Our case demonstrates the potential good outcome in patients with advanced renal disease, suggesting that, until further data are available, appropriately selected patients with renal dysfunction should not be excluded from thrombolysis.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Khella S, Bleicher MB. Stroke and its prevention in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;2:1343–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seliger SL, Gillen DL, Tirschwell D, et al. Risk factors for incident stroke among patients with end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003;14:2623–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seliger SL, Gillen DL, Longstreth WT, Jr, et al. Elevated risk of stroke among patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 2003;64:603–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedges SJ, Dehoney SB, Hooper JS, et al. Evidence-based treatment recommendations for uraemic bleeding. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2007;3:138–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Keyser J, Gdovinova Z, Uyttenboogaart M, et al. Intravenous alteplase for stroke: beyond the guidelines and in particular clinical situations. Stroke 2007;38:2612–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palacio S, Gonzales NR, Sangha NS, et al. Thrombolysis for acute stroke in haemodialysis: international survey of expert opinion. CJASN 2011;6:1089–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyrer PA, Fluri F, Gisler D, et al. Renal function and outcome among stroke patients treated with IV thrombolysis. Neurology 2008;71:1548–0 Am J Kidney Dis 2009;54:468–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agrawal V, Rai B, Fellows J, et al. In-hospital outcomes with thrombolytic therapy in patients with renal dysfunction presenting with acute ischaemic stroke. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:1150–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naganuma M, Koga M, Shiokawa Y, et al. Reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate is associated with stroke outcome after intravenous r-tPA: the Stroke Acute Management with Urgent Risk-Factor Assessment and Improvement (SAMURAI) r-tPA registry. Cerebrovasc Dis 2011;31:123–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Eriksson N, et al. Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-MOnitoring STudy Investigators: multivariable analysis of outcome predictors and adjustment of main outcome results to baseline data profile in randomized controlled trials: Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-MOnitoring STudy (SITS-MOST). Stroke 2008;39:3316–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams HP, Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischaemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease and quality of care outcomes in research interdisciplinary working groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Circulation 2007;115:478–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]