Abstract

We report an immunocompetent 24-year-old man who presented with a severe, invasive non-typhoidal salmonella (iNTS) infection. He presented with lumbar back pain associated with fever and rigours, which had been preceded by diarrhoea. Blood cultures grew Salmonella enteritidis. An MRI scan of his pelvis and spine showed that he had a small gluteal abscess and sacroiliitis. His condition subsequently deteriorated due to the development of a secondary pneumonia and respiratory failure. He was managed conservatively with 2 weeks of intravenous ceftriaxone, followed by 6 weeks of oral ciprofloxacin. Detailed investigations did not reveal any predisposing factors or evidence of an underlying immunodeficiency. Follow-up showed complete resolution of symptoms with no long-term sequelae.

Background

This case is important for a number of reasons. Globally, invasive non-typhoidal salmonella (iNTS) infection is increasing and has emerged as one of the leading causes of morbidity and deaths in sub-Saharan Africa.1 We describe a case of iNTS infection with multi-organ involvement, which is extremely rare in the developed world. Furthermore, most patients have an underlying immunodeficiency or predisposing condition.2 This was not the case in our patient, thus making it a very unique presentation. To our knowledge, invasive Salmonella enteritidis infection in an immunocompetent host, resulting in a gluteal abscess and sacroiliitis complicated by pneumonia, has not been reported previously.

Case presentation

A previously fit and healthy 24-year-old Caucasian man presented to the emergency department with a 1-day history of severe lumbar back pain radiating into the right buttock and lower limb, rendering him unable to walk. He also complained of fever and rigours, associated with a generalised headache and vomiting. The patient had been suffering with 7 days of bloody diarrhoea, which had ceased 2 days prior to admission. There was no significant medical history or relevant risk factors for infection, such as travel and pets. He was not on any regular medication and did not report any allergies. He did not smoke or drink any alcohol. There was no significant family history.

His initial observations were as follows: pulse 92 beats/min, blood pressure 101/50 mm Hg, temperature 39.2°C, saturations 96% on air and respiratory rate 22/min. He was fully conscious with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15/15 and a blood sugar of 6.9 mmol/l. Initial examination elicited severe pain in the right buttock on palpation. There were no rashes or signs of meningism. The remainder of his examination, including neurological examination, was unremarkable.

He was transferred to the acute medical unit and was initially managed with intravenous fluids. He underwent investigations for a presumptive diagnosis of discitis with blood cultures and an MRI spine. The following day, he was started on intravenous co-amoxiclav as a Gram-negative organism had been identified in his blood culture. An ultrasound showed an ill-defined region within the right gluteus maximus; an MRI of the pelvis was suggested for further characterisation.

He was subsequently transferred to a medical ward, where he was noted to be significantly hypoxic and persistently febrile by the nursing staff. He was started on oxygen and the doctors were informed. At this stage, it became apparent that he was growing S enteritidis in his blood cultures and his antibiotic was therefore changed to ceftriaxone. Unfortunately, his clinical condition deteriorated rapidly over the following hours and he became profoundly septic, hypoxic and had a significant metabolic acidosis. He was peripherally shut down and mildly icteric. His observations showed cardiorespiratory compromise (table 1) and auscultation of the chest revealed fine bibasal crackles. A chest x-ray showed left lower lobe consolidation. Other observations are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Observations for the patient on the day of admission compared with day 4

| On admission | Day 4 | |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory rate | 18/min | 18/min |

| Oxygen saturations | 96% on air | 82% on air |

| Heart rate | 107 bpm | 100 bpm |

| Blood pressure | 100/60 mm Hg | 110/60 mm Hg |

| Capillary refill time | <2 s | 5 s |

Dissemination of this pathogen, which is usually localised to the gut, brought into question whether he was immunocompromised. At this point, the patient was transferred to the infectious disease unit.

Investigations

Routine blood tests showed the following results:

| White cell count | 5.7×109/l |

| Haemoglobin | 11.9 g/dl |

| Total lymphocyte count | 0.27×109/l |

| Neutrophil count | 5.28×109/l |

| Platelets | 90×109/l |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 132 iu/l |

| Alanine transaminase | 58 iu/l |

| Total bilirubin | 54 umol/l |

| C reactive protein | 296 mg/l |

The remainder of his blood, including urea, creatine and electrolytes, was all normal.

Investigations for immunodeficiency

HIV antibody/antigen test: negative×2.

Haemoglobin electrophoresis: normal.

Lymphocyte profile showed normal numbers of T cells, natural killer cells and polyclonal B cells in his peripheral blood and a normal neutrophil oxidative burst, which excluded chronic granulomatous disease.

There was no evidence of type I cytokine deficiency—normal interferon-γ and interleukin 12 (IL-12) pathways.

Microbiology

Blood cultures×2: grew S enteritidis phage type 56.

Sensitivity to: ciprofloxacin, cefotaxime/ceftriaxone, azithromycin.

E test: ciprofloxacin 0.016 mg/l, azithromycin 2 mg/l.

Imaging

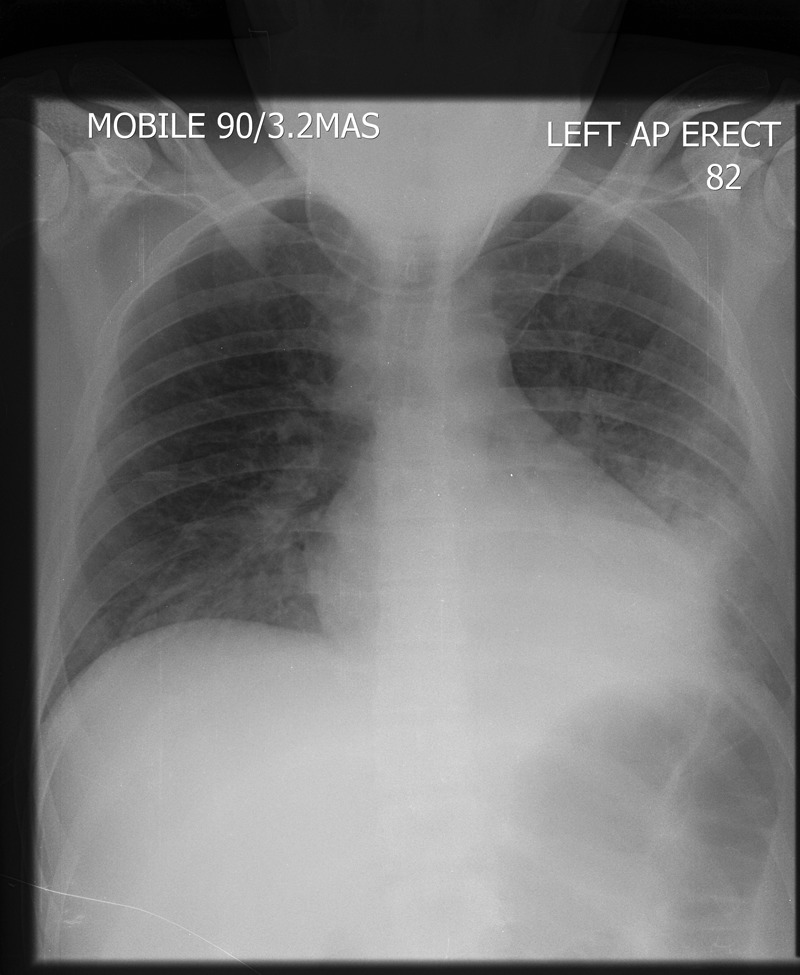

Admission: normal chest x-ray (figure 1) and normal MRI spine.

Figure 1.

Admission chest x-ray showing clear lung fields.

Ultrasound pelvis: A 2.8 cm×2 cm ill-defined region within the right gluteus maximus muscle.

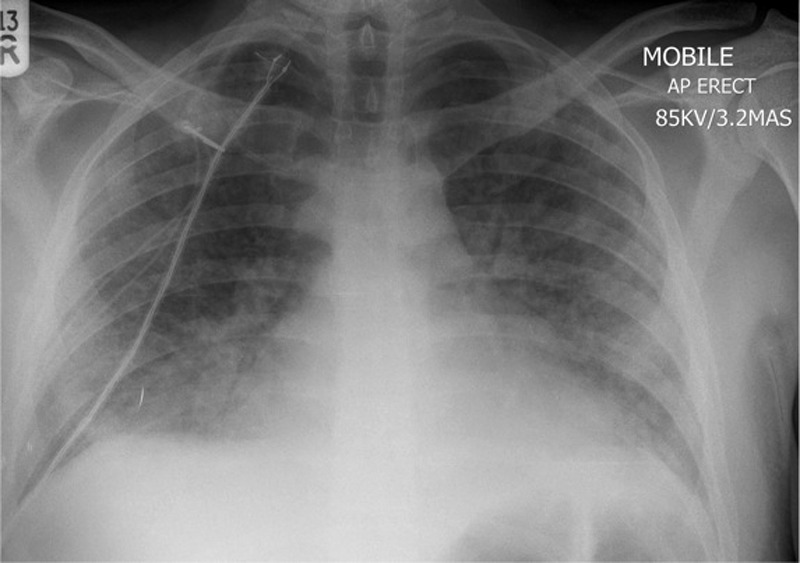

Day 3: chest x-ray showed left lower lobe consolidation (figure 2).

Figure 2.

A portable chest x-ray (day 3) showing a new left lower lobe consolidation.

Day 6: a repeated chest x-ray showing progressive bilateral interstitial changes (figure 3).

Figure 3.

A portable chest x-ray (day 6) showing bilateral interstitial shadowing consistent with worsening of infection or an acute respiratory distress syndrome picture.

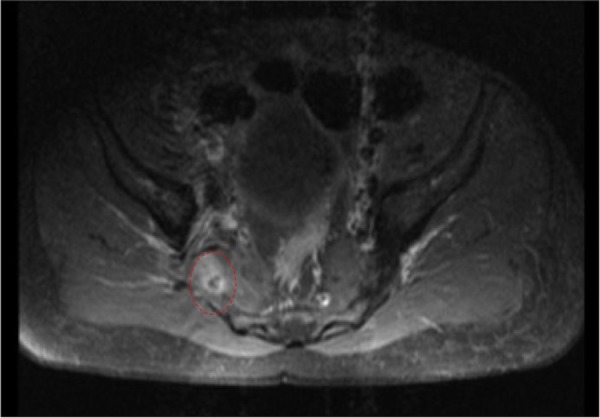

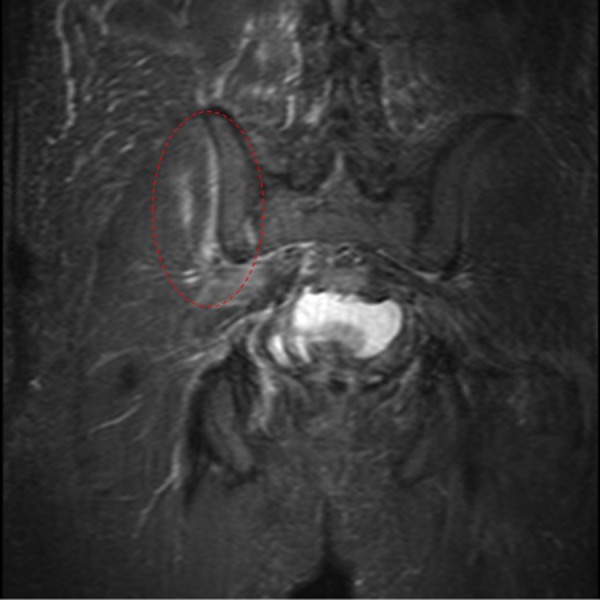

Day 6: an MRI of the pelvis with contrast showed a small gluteal abscess inferior to the right sacroiliac joint (SIJ) (figure 4). A right SIJ effusion with surrounding bone marrow oedema was also demonstrated (figure 5).

Figure 4.

MRI of the pelvis showing a small right gluteal abscess with surrounding oedema.

Figure 5.

MRI of the pelvis showing the right sacroiliac joint effusion with surrounding bone marrow oedema.

A repeated chest x-ray was performed on day 12 of his admission and demonstrated clear lung fields.

Differential diagnosis

Discitis

Gastroenteritis

Septic arthritis

Osteomyelitis

Meningitis

Treatment

Initially, the patient was treated with co-amoxiclav, which was started on day 2. On day 3, blood cultures grew S. enteritidis. He was treated with intravenous ceftriaxone for 14 days. His acute respiratory deterioration was managed with high-flow oxygen and close supervision of the critical care outreach team. He was initially quite difficult to wean off the oxygen, and a repeated chest x-ray showed progressive interstitial changes bilaterally, which could have been representative of worsening infection or acute respiratory distress syndrome. The orthopaedic team reviewed his case and decided that surgical drainage would be difficult given the location, so systemic antibiotic therapy was continued. By day 8, the patient appeared to be improving clinically with decreasing oxygen requirements and his temperature was settling. After completing 2 weeks of intravenous ceftriaxone, he continued taking oral ciprofloxacin for another 6 weeks to ensure absolute eradication of the organism.

Outcome and follow-up

On discharge, 15 days after admission, he still had pain in his buttocks with reduced mobility requiring crutches and physiotherapy. He had no fever, and oxygen saturations were 100% on air. He was discharged on oral antibiotics and continued a 4-week follow-up appointment in the infectious disease clinic. When seen in the clinic, he had fully recovered and was back at work. His inflammatory markers had all returned to normal. Extensive investigations by the immunologists for evidence of inherited immunodeficiencies did not reveal any abnormalities. At this point, he was discharged from our care with no long-term sequelae.

The patient believed that he contracted the infection from a chicken burger he had consumed in a fast food restaurant, prior to his illness. The infection was notified to the Health Protection Agency (HPA).

Discussion

Salmonellae are Gram-negative bacilli that cause a number of clinical manifestations in humans. Non-typhoidal salmonellae (NTS), including S. enteritidis, Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella newport, are a very common cause of gastroenteritis worldwide. S. enteritidis is most often a foodborne infection associated with poorly prepared or raw eggs and poultry. It can also be contracted from pet animals and contaminated pet food.3 The iNTS infection has emerged as an important cause of bacteraemia and significant mortality worldwide. It is endemic in sub-Saharan Africa and one of the most common isolates from febrile patients, both in adults and children.4 In high-income countries, NTS usually cause a self-limiting diarrhoeal illness, with a small proportion developing bacteraemia and extra-intestinal focal infections.

The International Bacteraemia Surveillance Collaborative recently reported the first population-based incidence of iNTS infection in the developed world.5 They documented cases between 2000 and 2007 in Finland, Australia, Denmark and Canada. They reported a crude annual incidence of 0.81/100 000. Interestingly, they also showed a gradual increase in the incidence of iNTS infection over the period of the study. At present, there are no similar data available for the UK, even though the HPA publishes figures for the overall incidence of NTS infections. In 2010,HPA reported 2444 cases of S. enteritidis infection in UK and Wales, which has shown a downward trend in incidence over the past decade.6

A recent review from Cambridge, UK documented over 1000 cases of salmonella infections presenting to their hospital over a 10-year period.7 However, they only reported 21 cases of iNTS infection, and 14 of these cases had an underlying immunosuppression or presented at extremes of age (10 years>age>80 years).

Using PubMed, we reviewed over 50 case reports of invasive S enteritidis infection with focal seeding resulting in infections at multiple locations. It has been reported to cause musculoskeletal, central nervous system, pulmonary, cardiovascular and urinary infections.8–10 Nearly all the cases presented in patients at the extremes of age or had underlying predisposing factors. Factors included sickle cell disease, immunosuppression, malignancies, immunomodulating therapy and systemic lupus erythematosus.11–13 One case documented septicaemia associated with IL-12 receptor deficiency; testing in our patient showed an appropriate response to IL-12.14 A Spanish study detailed 35 invasive salmonella infections presenting to their hospital over a 10-year period.8 They reported infections involving numerous sites, including four cases of pulmonary infection and three cases of bone infection. All of these seven cases had predisposing factors apart from one 16-year-old girl who had an evidence of sacroiliitis and cultured S enteritidis from her urine. Two of the pulmonary cases died and had underlying malignancy. Knight et al15 reported two cases of pulmonary NTS infections; however, both patients had undiagnosed type II diabetes mellitus. Schmidt et al16 reported a case of Salmonella choleraesuis sacroiliitis in a 17-year-old school boy. Aligeti et al17 reported a case of S typhimurium gluteal abscess in the absence of risk factors for salmonellosis.

Our patient was a previously healthy 24-year-old man who presented with S enteritidis bacteraemia, complicated by a gluteal abscess and associated sacroiliitis. His condition deteriorated significantly on day 3 of his admission due to a left lower lobe pneumonia causing respiratory failure. It is impossible to be certain whether this was due to seeding of his salmonella bacteraemia or a healthcare-associated pneumonia (HAP). However, it was very early on in the course of his illness and he was on appropriate intravenous antibiotics to cover HAP. Unfortunately, we did not obtain any positive cultures from respiratory samples to definitely prove this. To our knowledge, there are no similar published cases on immunocompetent hosts in the English literature.

The fluoroquinolones and the third-generation cephalosporins are appropriate antibiotic choices for the management of iNTS infections.18 Extraintestinal infection often requires surgical debridement; however, the orthopaedic surgeons deemed that his abscess was too small to warrant drainage. We, therefore, opted for prolonged antibiotics to successfully treat his infection. The optimal length of treatment is dependent on the patient's immune status and the site of infection. A minimum of 3 weeks’ therapy is recommended, and our patient was treated with a total of an 8-week course of antibiotics. The emergence of resistance to these antibiotics has been reported in NTS infection.19 20 Our patient was fully susceptible to the fluoroquinolones ( minimum inhibitory concentration, 0.016 mg/l) and third-generation cephalosporins.

Barrier nursing and hand washing are important to prevent onward transmission, and NTS bacteraemia is a notifiable disease. In addition to antimicrobial therapy, the detection of an iNTS infection should prompt a thorough search for immunodeficiency or predisposing factors including HIV testing, sickle cell screen, T-lymphocyte and cytokine profile testing. In our patient, there was no evidence of any predisposing factors. At follow-up, he was completely asymptomatic and had no evidence of long-term sequelae.

In summary, we present a unique case of iNTS infection with multi-focal seeding in an immunocompetent host. This condition, which has emerged as one of the most important diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, is likely to assume increasing importance in the developed world.

Learning points.

How unusual is it for Salmonella enteritidis septicaemia to present in a young, seemingly immunocompetent patient?

The location of other foci of infection in this presentation, that is, the lung, sacroiliac joint and the pelvis.

The investigation and management of an acutely unwell patient from admission to transfer to other wards.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, et al. Invasive non-typhoidal salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet 2012;379:2489–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhanoa A, Fatt Q. Non-typhoidal salmonella bacteraemia: epidemiology, clinical characteristics and its’ association with severe immunosuppression. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2009;8:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hohmann EL.2012. Microbiology and epidemiology of salmonellosis. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/microbiology-and-epidemiology-of-salmonellosis?source=search_result&search=nontyphoidal+salmonella&selectedTitle=3~15 (accessed 14 Aug 2012)

- 4.Morpeth SC, Ramadhani HO, Crump JA. Invasive non-typhi salmonella disease in Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:606–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laupland KB, Schonheyder HC, Kennedy KJ, et al. Salmonella enterica bacteraemia: a multi-national population-based cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health Protection Agency Salmonella by serotype: epidemiological data on all human isolates reported to the heath protection agency centre for infections England and wales 2000–2010. 2011. http://www.hpa.org.uk/Topics/InfectiousDiseases/InfectionsAZ/Salmonella/EpidemiologicalData/salmDataHuman/ (accessed 20 July 2012)

- 7.Matheson N, Kingsley RA, Sturgess K, et al. Ten years experience of salmonella infections in Cambridge, UK. J Infect 2010;60:21–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munigangaiah S, Khan H, Fleming P, et al. Septic arthritis of the adult ankle joint secondary to salmonella enteritidis: a case report. J Foot Ankle Surg 2011;50:593–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez M, de Diego I, Martinez N, et al. Nontyphoidal salmonella causing focal infections in patients admitted at a Spanish general hospital during an 11-year period (1991–2001). Int J Med Microbiol 2006;296:211–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samonis G, Maraki S, Kouroussis C, et al. Salmonella enterica pneumonia in a patient with lung cancer. J Clin Microbiol 2003;41:5820–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Herte RI, Haidar RK, Uthman IW, et al. Salmonella enteritidis bacteremia with septic arthritis of the sacroiliac joint in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and review of the literature. J Med Liban 2011;59:235–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein M, Houston S, Pozniak A, et al. HIV infection and salmonella septic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1993;11:187–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henderson RC, Rosenstein BD. Salmonella septic and aseptic arthritis in sickle-cell disease. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989;248:261–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carvalho BT, Iazzetti AV, Ferrarini MA, et al. Salmonella septicemia associated with interleukin 12 receptor beta1 (IL-12Rbeta1) deficiency. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2003;79:273–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knight JC, Knight M, Smith MJ. Two cases of pulmonary complications associated with a recently recognised salmonella enteritidis phage type, 21b, affecting immunocompetent adults. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2000;19:725–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt DB, Meier R, Ochsner PE, et al. Acute bacterial sacroiliitis caused by salmonella choleraesuis. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1988;113:1474–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aligeti VR, Brewer SC, Khouzam RN, et al. . Primary gluteal abscess due to salmonella typhimurium: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci 2007;333:128–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohmann EL.2012. Nontyphoidal salmonella bacteremia. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/nontyphoidal-salmonella-bacteremia?source=search_result&search=nontyphoidal+salmonella&selectedTitle=1~15 (accessed 14 Aug 2012)

- 19.Stevenson JE, Gay K, Barrett TJ, et al. Increase in nalidixic acid resistance among non-typhi salmonella enterica isolates in the United States from 1996 to 2003. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007;51:195–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee HY, Su LH, Tsai MH, et al. High rate of reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone among nontyphoid salmonella clinical isolates in Asia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:2696–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]