Abstract

In India, Atlantoaxial dislocation (AAD) is the commonest skeletal craniovertebral junction (CVJ) anomaly, followed by occipitalisation of atlas and basilar invagination. The usual presentation is progressive neurological deficit (76–95% cases) involving the high cervical cord, lower brainstem and cranial nerves. The association between vertebro-basilar insufficiency and skeletal CVJ anomalies is well recognised and angiographic abnormalities of the vertebrobasilar arteries and their branches have been reported; however, initial presentation of CVJ anomaly as thalamic syndrome due to posterior circulation stroke is extremely rare. Here, we report one such rare case of thalamic syndrome as the initial presentation of CVJ anomaly with AAD.

Background

Atlantoaxial dislocation (AAD) is the commonest skeletal craniovertebral junction (CVJ) anomaly reported from India. However, posterior circulation stroke due to vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) is extremely rare presentation of CVJ anomalies. We report one such rare case, where a patient with AAD presented with thalamic syndrome in form of severe pain on one-half of the body.

Case presentation

A 17-year-old male student, presented to us with a 2-month history of a sudden onset tingling sensation over left half of body including face. It was accompanied by forgetfulness and apathy. There was no history of headache, altered sensorium, vomiting, visual disturbance, diplopia, cranial nerve involvement, speech difficulty, sensory loss, motor weakness, limb incoordination or any bladder disturbance. Within 7–8 days of onset, his paraesthesia improved, but the impairment of memory and apathy persisted for next 1 month which was then followed by partial recovery. This was associated with difficulty in writing and reading, interfering with his studies. There was no history suggestive of diabetes, hypertension, rheumatic heart disease or any neck pain, trauma or manipulation.

On examination at the time of presentation, he was conscious and oriented. On general examination, cranium and spine were normal. His hair line and height:neck ratios (11.5:1) were normal. Vitals were preserved and systemic examination was normal. His mini mental status examination score was 26/30. On detailed cognitive examination, attention was normal and language functions were intact. His memory evaluation revealed impaired recent memory with preserved remote memory. Calculation was impaired, but copying and construction were normal; and there was no finger agnosia, apraxia or right-left confusion. On cranial nerve examination, visual acuity, field of vision and fundus examinations were normal. Other cranial nerves were intact. Motor and sensory system examination was normal. Deep-tendon reflexes were preserved and plantars were flexor. Coordination was normal. In view of the history of a sudden onset unilateral paraesthesia accompanied by recent memory loss and apathy with subsequent recovery over the next few days, a possibility of a posterior circulation stroke leading to thalamic syndrome was entertained. For the presenting clinical features, MRI of brain was done and found to be associated with CVJ anomaly. Patient has been operated for atlantoaxial dislocation by Neurosurgeon, subsequently referred to us for further evaluation. So, association of a young stroke without any obvious risk factors and the presence of CVJ anomaly were considered.

Investigations

His investigations revealed a normal haemogram and blood sugar. Lipid profile, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, electrolytes, liver function tests, kidney function test and homocysteine levels were within the normal range. Tests for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody and HIV were negative. Chest x-ray, ECG, two-dimensional echocardiography and carotid Doppler studies were normal. MRI of the brain and CV junction revealed multiple small infarcts involving bilateral thalamus and right cerebellar hemispheres (figure 1). AAD with indentation over the cervicomedullary junction during neck flexion and increase in atlas-dens interval (>3 mm) was also observed (figures 2 and 3). On MR angiography of the brain and neck, there was a partial attenuation and kinking of right vertebral artery (figure 4).

Figure 1.

(A) T2-flair and (B) T2-weighted axial MRI of brain showing multiple hyperintensities in bilateral thalamic region. (C and D) Diffusion weighted images showing restriction in bilateral thalamus and right cerebellar region suggestive of infarct.

Figure 2.

T2-weighted MRI cervical spine saggital section showing indentation of the cervico-medullary junction by the odontoid process during neck flexion. The corresponding increase in atlas-dens interval (>3 mm) was demonstrated in same view.

Figure 3.

CT cervical spine saggital section revealed the same findings.

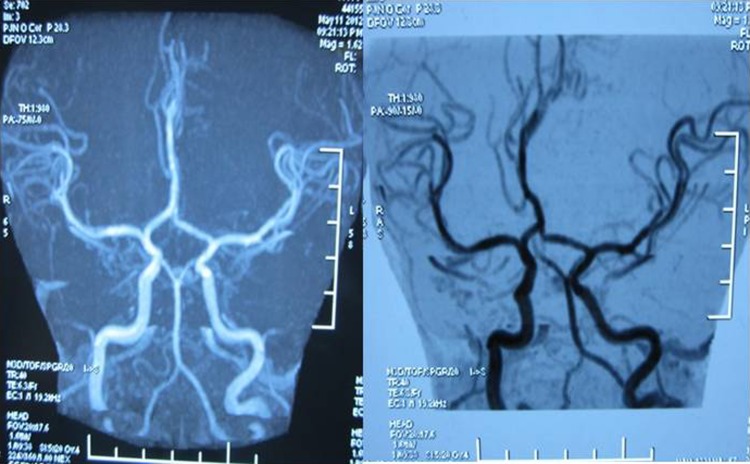

Figure 4.

MR angiography brain showing attenuation with kinking of right vertebral artery.

Treatment

After surgical intervention, patient has been advised neck immobilisation.

Outcome and follow-up

The follow-up after 1 month revealed complete recovery.

Discussion

Congenital CVJ anomalies comprises of the developmental defects of the atlas and axis vertebrae along with occipital bone surrounding the foramen magnum. CVJ developed from the mesodermal somites to form four occipital and two cervical sclerotomes, during fetal development. Defects during embryogenesis occurring in the third and fourth week of gestation can cause CVJ anomalies which may implicate either the neural or skeletal structures or both.1 2 The bony anomalies may affect the occiput (platybasia and basilar invagination) or the atlas (AAD and occipitalisation of the atlas) or axis (odontoid malformations) and other vertebral defect (Klippel-Feil anomaly).1 2

Neural or soft tissue anomalies include Syrinx, Chiari malformation, and Dandy-Walker syndrome).1 2 Presently, epidemiological data is lacking and most of the information is derived from retrospective reviews of hospital records regarding skeletal CVJ anomalies. As compared to the West, CVJ anomalies are more common in India.1 In India AAD is the commonest, followed by occipitalisation of atlas, whereas basilar invagination is more common in the West. The commonest anomalies implicated are AAD, occipitalisation of atlas and fusion of C2 and C3 vertebrae, occurring in combination in India.1 Chopra et al3 reported 82 cases of CVJ anomalies and found congenital AAD was the commonest anomaly (56.1%) encountered in India. Similarly Bharucha and Dastur4 analysed 40 cases of CVJ anomalies and found AAD was more common both due to congenital or acquired cause. Yerramneni et al5 studied 100 cases of CVJ anomalies and found developmental pathology is the commonest cause. Among the infective processes, tuberculosis (TB) is an important condition to affect spine. CVJ TB is an extremely rare condition, accounting for 0.3–1% of all cases of spinal TB.6 However due to lack of Indian data about acquired pathologies associated with AAD, cause still remains unknown. The mean age of manifestation of CVJ anomalies is around 25 years, although they may present since birth. Men are affected more commonly and in nearly 50% of the cases, trivial neck trauma may be identified as predisposing factor.2 In our case, the patient was a male and became symptomatic first at 17 years of age without any history of preceding neck manipulation or trauma. The common presentation of skeletal CVJ anomalies is progressive neurological deficit (76–95% cases) involving the high cervical cord, brainstem, and lower cranial nerves.1 They clinically present as spastic quadriparesis (100% in some series), but Brown-Séquard syndrome and hemiparesis can also occur.1 Around 33% of cases present with sensory loss and loss of proprioception, which is more prominent in fingers than toes.1 2 Lower cranial nerves are involved in 12%, and cerebellar signs are seen in 10% of cases.1 2 Twenty-five per cent cases show bilateral hand wasting which is a false localising sign.1 2 Pseudoathetosis and mirror movements are useful but infrequent signs in the diagnosis of CVJ disorders. Transient deficits which include motor and sensory deficit, visual disturbance, inability to speak or dysarthria, and bladder disturbances are seen in around 20% patients. These may possibly be due to platelet microembolisation in the territory of vertebrobasilar artery and last for duration ranging from a few minutes to hours.1 2 However our patient presented with acute onset unilateral paraesthesia and memory dysfunction, as a case of thalamic syndrome due to posterior circulation stroke. Posterior circulation strokes account for 10–15% of all strokes and thalamic syndrome affects approximately 8% of all stroke patients.7 Dejerine and Roussy initially described the term thalamic syndrome.8 According to previous studies around 30% of cases with VBI undergo cervical spine x-rays, therefore association between skeletal CVJ anomalies and VBI may be underestimated and only 11% are investigated using proper flexion and extension views of the CVJ.9 10 However, as observed in our case, CV junction anomalies presenting as posterior circulation stroke is extremely rare.1 Wadia et al1 in a study of 115 patients with CVJ abnormalities, have reported symptoms of VBI with posterior circulation stroke in three, and angiographic narrowing of the vertebral arteries at the level of the atlantoaxial joint in one patient with symptoms of VBI. Another study of 40 patients with CV junction anomalies from India, has reported symptoms of VBI in three, but stroke in none of the cases.8 In a series of 200 cases with CVJ anomalies, Satishchandra et al11 have reported acute stroke in the vertebrobasilar artery territory in eight cases. The dual supply through the two vertebral arteries and the adequacy of the circulation from the circle of Willis may be the possible explanation for clinical rarity of posterior circulation infarcts in CVJ anomalies.9 The commonest CVJ anomaly implicated in causing stroke or VBI is AAD,1 9 12–15 followed by odontoid aplasia,15 basilar impression, occipitalisation of the atlas, Klippel-Feil anomaly,1 and anomalous osseous process of the occipital bone projecting to the posterior arch of the atlas.16 In most reports of CVJ anomalies with stroke, cerebellar infarction is common but multiple areas including bilateral thalamus supplied by the vertebrobasilar system can be affected as was observed in our case. Vertebral arteries are most commonly affected as is evident on angiography1 12 13 but branches of the vertebral, basilar and posterior cerebral arteries may be attenuated or poorly developed with thromboembolism being sometimes reported.12 14–16 Vertebral artery dissection and posterior circulation stroke following neck manipulation has been reported in three cases with basilar invagination; during intubation in one case, following cervical traction in another case, and no obvious cause in one case.17–19 In one study of seven cases with AAD and VBI, DSA (digital subtraction angiography)/MRA revealed obstruction of the vertebral artery at the C1 through C2 level on one side and a ‘stretched loop sign’ (shortened and straighter loop of the third segment of the VA) on the contralateral side.20 In our case there was a partial attenuation of right vertebral artery along with kinking. The association of VBI with CVJ anomalies has also been studied using Technetium 99 m ethylenecysteine dimer brain SPECT (single photon emission CT). In a cohort of 19 patients, authors studied cerebellar perfusion with congenital CVJ anomalies, with or without VBI.9 They reported decreased perfusion in 75% of the symptomatic as compared with 14% of the asymptomatic cases prior to surgery. The plausible explanation may be due to thromboembolism and presence of intimal damage of the vessels secondary to low-grade chronic microtrauma due to repeated flexion and extension of the neck. The operative outcomes have been assessed by authors in 12 patients with symptoms of VBI (episodic vertigo, drop attacks, dysarthria and visual disturbances) and two patients with cerebellar infarctions. Improvement in cerebellar perfusion and the symptoms of VBI were observed in eight patients (88.9% cases) in the symptomatic group and none of the patients in the asymptomatic group, 1-month postsurgery.9

Learning points.

Physicians should be aware of the uncommon presentations of craniovertebral junction (CVJ) anomalies.

All young patients presenting with features of vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) or posterior circulation stroke should be screened for CVJ anomalies.

The outcome of corrective surgery in these patients is determined by the presence or absence of angiographic abnormalities of the vertebrobasilar arteries or a prior history of VBI or stroke remains inquisitive.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Wadia NH, Bhatt MH, Desai MM. Myelopathy of congenital atlantoaxial dislocation. In: Chopra JS, ed. Advances in neurology, vol. 2 Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers, B.V. (Biomedical division) 1990:455–64 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shukla R, Nag D. Craniovertebral anomalies: the Indian scene. Neurosci Today 1997;1:51–8 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chopra JS, Sawhney IM, Kak VK, et al. Craniovertebral anomalies: a study of 82 cases. Br J Neurosurg 1988;2:455–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bharucha EP, Dastur HM. Craniovertebral anomalies (a report on 40 cases). Brain 1964;87:469–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yerramneni VK, Chandra PS, Kale SS, et al. A 6-year experience of 100 cases of pediatric bony craniovertebral junction abnormalities: treatment and outcomes. Pediatr Neurosurg 2011;47:45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai SS. Early diagnosis of spinal tuberculosis by MRI. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994;76:863–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schott GD. From thalamic syndrome to central post stroke pain. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;61:560–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Déjérine J, Roussy G. Le syndrome thalamique. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1906;14:521–32 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agrawal D, Gowda NK, Bal CS, et al. Have cranio-vertebral junction anomalies been overlooked as a cause of vertebro-basilar insufficiency? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:846–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorenstan KJ, Schrospshire LC, Ahn HS. Congenital odontoid aplasia and posterior circulation stroke in childhood. Ann Neurol 1988;23:410–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satishchandra P, Ramdas GV, Gaikwad SB. Cranio-vertebral junction anomalies with posterior circulation stroke. Neurocon 2001;23–32 Abstract book [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ando S, Matsui Y, Fujii J, et al. Cerebellar infarctions secondary to cranio-cervical anomalies: a case report. Nippon Geka Hokan 1994;63:148–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer WD, Haller JS, Wolpert SM. Occlusive vertebrobasilar artery disease associated with cervical spine anomaly. Am J Dis Child 1975;129:492–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shim SC, Yoo DH, Lee JK, et al. Multiple cerebellar infarctions due to vertebral artery obstruction and bulbar symptoms associated with vertical subluxation and atlanto-occipital subluxation in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 1998;25:2464–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips PC, Lorentsen KJ, Shropshire LC, et al. Congenital odontoid aplasia and posterior circulation stroke in childhood. Ann Neurol 1988;23:410–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tominaga T, Takahashi T, Shimizu H, et al. Rotational vertebral artery occlusion from occipital bone anomaly: a rare cause of embolic stroke. Case Report. J Neurosurg 2002;97:1456–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panda S, Ravishankar S, Nagaraja D. Bilateral vertebral artery dissection caused by atlantoaxial dislocation. JAPI 2010;58:186–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zotter H, Zenz W, Gallistl S, et al. Stroke following appendectomy under general anaesthesia in a patient with basilar impression. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2000;44:1271–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickinson LD, Tuite GF, Colon GP, et al. Vertebral artery dissection related to basilar impression: case report. Neurosurg 1995;36:835–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sawlani V, Behari S, Salunke P, et al. ‘Stretched loop sign’ of the vertebral artery: a predictor of vertebrobasilar insufficiency in atlantoaxial dislocation. Surg Neurol 2006;66:298–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]