Abstract

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) is recognised in most cases after diagnosis of malignant and benign haematological tumours. PNP usually presents with severe and diffuse oral ulcerations, ocular lesions, lichen planus-like skin lesions and frequently genital ulcerations. We describe the uncommon case of a patient unaware of any neoplasia with a unique ulcerated oral lesion with histological (acantholysis of the basal epithelial layer, necrotic keratinocytes and pronounced regenerative hyperplasia) and immunofluorescent (direct immunofluorescence test exhibited immunoglobulin IgG, fibrinogen and C3 deposition in intercellular areas and along the basement membrane; indirect immunofluorescence test performed on rat bladder showed bright fluorescence) features suggestive of PNP. Diagnosis of PNP was strengthened by the subsequent discovery of monoclonal gammopathy. The reported case is quite unusual if we consider the clinical appearance of the oral lesions and the patient's negative medical history. Following serological examinations, the patient proved to have monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), one of the most common premalignant plasma cell disorders.

Background

Pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease due to an auto-antibody reaction against keratinocyte cell surface proteins.1 2 It has been well-known for decades that some forms of pemphigus are associated with malignancies.3

‘Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP)’ was first described by Anhalt et al4 in 1990 as a new disease entity, and more than 200 cases of PNP have been reported worldwide since then.5–14 In most cases, the lesions are recognised after the diagnosis of malignant or benign haematological tumours,15 and are described as severe and diffuse oral ulcerations, ocular lesions, lichen planus-like skin lesions and frequently genital ulcerations.

We describe the uncommon case of a unique ulcerated oral lesion with histological and immunofluorescent features suggestive of PNP in a patient unaware of any neoplasia. Following serological examination, the patient proved to have monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), one of the most common premalignant plasma cell disorders.

Case presentation

In July 2011, a 79-year-old Caucasian man was referred to the University of Bologna, Department of Oral Sciences following the appearance of a red-based superficial lesion of the lower lip. The lesion was symptomatic and had appeared approximately 1 month earlier. Medical history-taking failed to disclose previous or actual disease and the patient was drug-free. Intraoral examination revealed a well-demarcated lesion on the mucosal side of the lower lip with a blister and bleeding erosion (figure 1). No other mucosal or skin lesions were detected during clinical examination.

Figure 1.

Blister and bleeding erosion of the lower lip.

Investigations

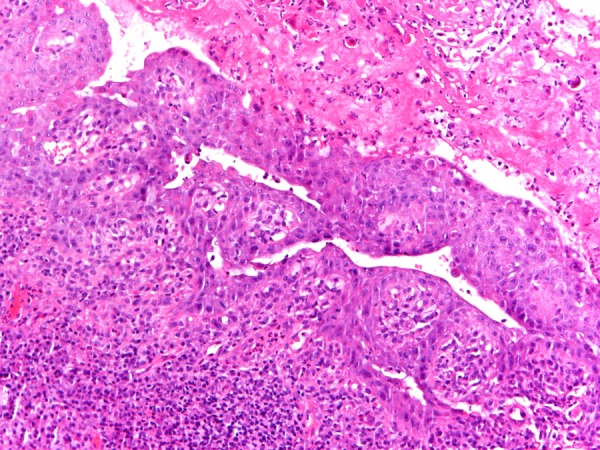

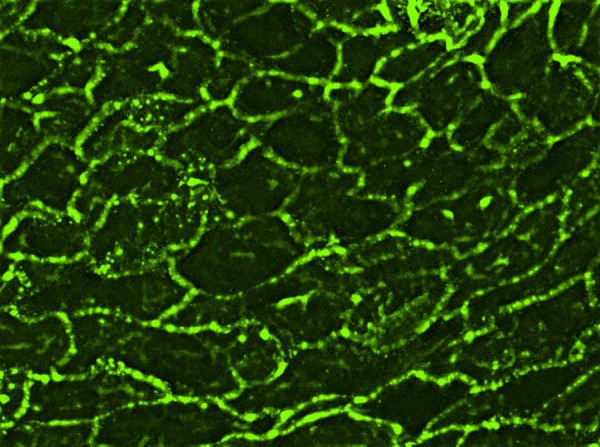

The patient underwent two incisional biopsies for histology and direct immunofluorescence (DIF). Histopathology revealed intraepithelial blistering and intense inflammatory acute and chronic cellular infiltration (figure 2). The basal epithelial layer showed acantholysis, necrotic keratinocytes and pronounced regenerative hyperplasia. DIF test exhibited immunoglobulin IgG, fibrinogen and C3 deposition in intercellular areas and along the basement membrane (figure 3). IgA and IgM were negative. Histopathology and DIF data did not show features of conventional pemphigus and raised the suspicion of PNP. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) test was performed using rat bladder as epithelial substrate and the patient's serum showed circulating antibodies against intercellular spaces and basement membrane with bright fluorescence.

Figure 2.

Histopathology of perilesional mucosa revealed intraepithelial blistering and intense inflammatory acute and chronic cellular infiltration.

Figure 3.

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional mucosa disclosed IgG deposition in the intercellular space.

Serological examination showed that the patient's serum immunoglobulin levels were 1731 mg/d for IgG, 93 mg/dl for IgA and 13 mg/dl for IgM. A narrow spike was observed in the γ-globulin region (24.1%) on electrophoresis, identified immunoelectrophoretically as an Ig γ-paraprotein. In-depth serological examination identified a monoclonal component of IgG/κ (1400 mg/dl).

The urinalysis was negative for Bence-Jones protein. Levels of urea and creatinine were normal. An expert haematologist formulated a final diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS) associated with PNP.

Differential diagnosis

A single ulcerative lesion of the oral mucosa not associated with proliferating epithelium can be the initial sign of several diseases, including viral and bacterial infections, local irritants, adverse drug reactions such as erythema multiforme and autoimmune diseases such as blistering diseases.

Treatment

Treatment consisted of topical applications of clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment, 3 times/day to help relieve burning and pain. The symptoms decreased in 2 weeks while the lesions disappeared completely after 60 days of treatment (figure 4). Topic corticosteroid therapy was then interrupted and the lesion reappears; the patient is actually dependent on local steroid therapy.

Figure 4.

Lower lip after 60 days of topical applications of clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment 3 times/day.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient is currently being followed up by both the haematology and oral sciences departments.

Discussion

An ulcerative lesion of the oral mucosa not associated with proliferating epithelium can be the initial sign of several diseases. PNP is a particular form of blistering disease typically associated with extraoral neoplasms (in 84% of cases haematologically related neoplasms, mostly non-Hodgkin's lymphoma4 16 17 and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia,16 18 less frequently Waldenstrom's macroglobulinaemia, Castleman's disease, thymoma and Hodgkin's lymphoma1 and in 16% of cases non-haematological neoplasms such as carcinoma, sarcoma16 18 and malignant melanoma19).

PNP diagnostic criteria were proposed by Anhalt et al4 in 1990. In the context of occult or confirmed neoplasia, they include mucocutaneous blistering and ulcerations, histopathological features such as acantholytic changes to the epithelium and epidermis with interface dermatitis, deposition of IgG and C3 in the intercellular areas and/or along the basement membrane, serum antibodies and demonstration of various desmoplakins and desmogleins in the serum.

Since few patients meet these original criteria, they were subsequently revised by Camisa and Helm7 who outlined major and minor criteria to diagnose PNP: the major signs include polymorphic mucocutaneous eruption, concurrent internal neoplasia and serum antibodies with a specific immunoprecipitation pattern; the minor signs include histological evidence of acantholysis, DIF showing intercellular and basement membrane staining and IIF staining with rat bladder epithelium. A patient fulfilling three or two major and at least two minor criteria can be diagnosed to have PNP.

Our case fulfils all the three minor Camisa and Helm's criteria. Histological and immunofluorescence features are all suggestive of PNP. There was histological evidence of acantholysis and distinctive deposition of IgG and C3 in intercellular areas and along the basement membrane also with fibrinogen deposition. Fibrinogen deposition is not a typical sign of autoimmune blistering diseases, but few reports described cases where PNP could mimic the characteristics of erosive mucosal lichen planus in histological findings and DIF.20 IIF test using rat bladder showed bright fluorescence.

Our case is quite unusual concerning the major criteria. Commonly, the clinical manifestations of PNP can vary widely, characterised by severe polymorphous lesions affecting the whole oral cavity,4 16 21 and sometimes extending to the pharynx, larynx and oesophagus causing soreness and dysphagia.4 The conjunctival mucosa is frequently involved with occasional progression to visual impairment.22 Genital ulceration is also common. Skin involvement shows variable appearances such as target lesions of erythema multiforme, blisters or lichen planus-like lesions.16 The present report describes a patient with a solitary lesion on the lower lip that had appeared one month earlier without any adjunctive sign. Although lower lip involvement has been reported as a first presentation of PNP,16 only one report to date has described a similar localised mucosal involvement as the sole manifestation.17

Another peculiarity is the good response to local corticosteroid therapy and the absence of any known underlying neoplasm when the lesion appeared, whereas it has been widely demonstrated that an underlying malignancy is mostly discovered before the eruption of lesions.2 Diagnostic suspicion of PNP was strengthened by the subsequent discovery of monoclonal gammopathy.

Association between PNP and monoclonal gammopathy is described in only 0.6% of all haematological disorders.16 MGUS is one of the most common premalignant plasma cell disorders and is a known precursor for multiple myeloma and other related plasma cell malignancies.23 An early diagnosis of this condition may be important for appropriate treatment and follow-up.

The pathogenetic mechanism of the association between PNP and MGUS remains unsettled. A patient with monoclonal gammopathy produces a monoclonal antibody that may or may not have an affinity of any strength for any given antigen. A possible mechanism reported in a similar case is that the patient's paraprotein has a weak affinity for an epidermal cell-surface and that the antibody gave rise to symptoms by an unclear mechanism in combination with a CD-8 lymphocyte-mediated cellular immune response.24

Learning points

A search for an underlying tumour is suggested even if a single lesion is indicative of a blistering disease.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) can occur as a solitary lesion of the oral cavity.

PNP leading to the diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance is uncommon.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Hashimoto T. Immunopathology of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Clin Dermatol 2001;19:675–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimyai-Asadi A, Jih MH. Paraneoplastic pemphigus. Int J Dermatol 2001;40:367–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krain LS, Bierman SM. Pemphigus vulgaris and internal malignancy. Cancer 1974;33:1091–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anhalt GJ, Kim SC, Stanley JRet al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus. An autoimmune mucocutaneous disease associated with neoplasia. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1729–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fullerton SH, Woodley DT, Smoller BR, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus with autoantibody deposition in bronchial epithelium after autologous bone marrow transplantation. JAMA 1992;267:1500–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camisa C, Helm TN, Liu YCet al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: a report of three cases including one long-term survivor. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;27:547–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camisa C, Helm TN. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a distinct neoplasia-induced autoimmune disease. Arch Dermatol 1993;129:883–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rybojad M, Leblanc T, Flageul Bet al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus in a child with a T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. Br J Dermatol 1993;128:418–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bystryn JC, Hodak E, Gao SQ, et al. A paraneoplastic mixed bullous skin disease associated with anti-skin antibodies and a B-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol 1993;129:870–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens SR, Griffiths CE, Anhalt GJ, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus presenting as a lichen planus pemphigoides-like eruption. Arch Dermatol 1993;129:866–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joly P, Thomine E, Gilbert Det al. Overlapping distribution of autoantibody specificities in paraneoplastic pemphigus and pemphigus vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol 1994;103:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishibori Y, Hashimoto T, Ishiko A, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: the first case report from Japan. Dermatology 1995;191:39–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsiao CJ, Hsu MM, Lee JY, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus in association with a retroperitoneal Castleman's disease presenting with a lichen planus pemphigoides-like eruption. A case report and review of literature. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:372–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan Z, Hua H, Gao Y. Paraneoplastic pemphigus characterized by polymorphic oral mucosal manifestations—report of two cases. Quintessence Int 2010;41:689–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tilakaratne W, Dissanayake M. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: a case report and review of literature. Oral Dis 2005;11:326–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joly P, Richard C, Gilbert Det al. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical, histologic, and immunologic features in the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:619–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bialy-Golan A, Brenner S, Anhalt GJ. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: oral involvement as the sole manifestation. Acta Derm Venereol 1996;76:253–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan I, Hodak E, Ackerman L, et al. Neoplasms associated with paraneoplastic pemphigus: a review with emphasis on non-hematologic malignancy and oral mucosal manifestations. Oral Oncol 2004;40:553–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaeppi H, Bauer JW, Hametner Ret al. A localized variant of paraneoplastic pemphigus: acantholysis associated with malignant melanoma. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:1249–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokokura H, Demitsu T, Kakurai Met al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus mimicking erosive mucosal lichen planus associated with primary hepatocellular carcinoma. J Dermatol 2006;33:842–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wade MS, Black MM. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: a brief update. Australas J Dermatol 2005;46:1–8; quiz 9–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam S, Stone MS, Goeken JAet al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus, cicatricial conjunctivitis, and acanthosis nigricans with pachydermatoglyphy in a patient with bronchogenic squamous cell carcinoma. Ophthalmology 1992;99:108–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kyle RA, Child JA, Anderson K, et al. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol 2003;121:749–57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lortscher DN, Amundson SA, Pittelkow MR. Multiple myeloma presenting as a novel mucocutaneous eruption. Dermatol Online J 2010;16:4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]