Abstract

Several surgical and orthodontic treatment options are available to disimpact the impacted teeth. But the closed eruption technique has the best long-term prognosis. The tooth is surgically exposed, an attachment is bonded to it, flap is resutured over it and an orthodontic extrusive force is delivered to bring the tooth into occlusion. This case report presents a case with multiple impacted teeth in which no syndrome or systemic conditions were detected. A 20-year-old female patient reported for orthodontic treatment with chief complaint of multiple unerupted permanent teeth and retained primary teeth. Radiographic examination revealed impacted 14, 15, 24, 25, 33, 34, 43 and 44. Surgical exposure of the impacted teeth was done after extraction of retained primary teeth. Forced eruption of these teeth was done by applying traction with closed eruption technique. After careful treatment planning followed by guided eruption of impacted teeth, patient finished with a significantly improved functional and aesthetic result.

Background

While impaction of teeth is widespread, multiple impacted teeth by itself is a rare condition often found in association with syndromes like Cleidocranial dysplasia, Gardeners syndrome, etc. This case report presents a case with multiple impacted teeth in which no syndrome or systemic conditions were detected involving both jaws. The presence of an impacted or missing permanent tooth can add significant complications to an otherwise straightforward case. When multiple impacted teeth are present, the complexity increases further. Developing a treatment sequence, determining appropriate anchorage and planning and executing sound biomechanics can be a challenge. The following case report illustrates a patient with 10 retained primary and eight impacted permanent teeth in which the impacted teeth were successfully aligned and brought into occlusion using closed eruption technique. Several surgical and orthodontic treatment options are available to disimpact impacted permanent teeth. But, the closed eruption technique has the best long-term prognosis.

Case presentation

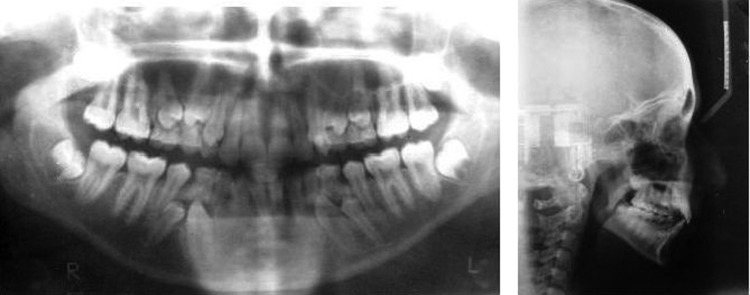

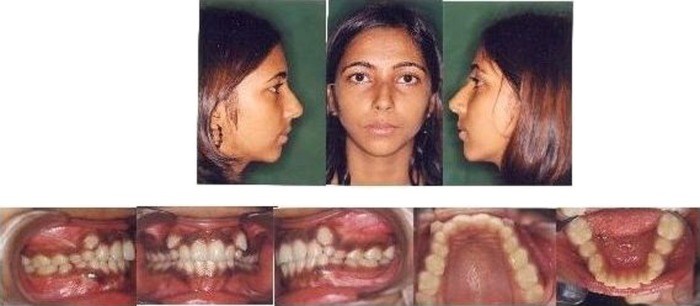

The patient was a 20-year-old woman, with a chief complaint of multiple retained primary teeth and the presence of double teeth in the upper front region. Review of medical history revealed the absence of any kind of medical problem. There was no history of trauma to either teeth or jaws. The patient had a leptoproscopic facial type with a convex profile. Intraoral examination revealed class I molar relation with retained primary canines, first and second molars in maxillary and mandibular arches, labially erupting maxillary canines and lower midline shift towards the right by 3 mm (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pretreatment photographs.

Investigations

Orthopantomogram, lateral cephalogram (figure 2) and intraoral periapical radiographs of impacted teeth were advised. Radiographic examination revealed impacted 14, 15, 24, 25, 33, 34, 43 and 44. Both the mandibular canines were 90° rotated mesiolingually. Mandibular canines and first premolars were buccally impacted. Maxillary first premolars were 90° rotated distolingually. Lateral cephalometric analysis revealed a normal skeletal relationship and model analysis showed adequate space in upper and lower arches for the alignment of impacted teeth. Mandibular occlusal view was taken to assess the progress during treatment.

Figure 2.

Pretreatment radiographs.

Treatment

The main treatment objective was guided eruption of the impacted teeth to obtain a functional occlusion with minimal impact on soft tissue profile.

Extraction of all the retained primary teeth was done and 0.022×0.028 inch Roth prescription Pre Adjusted Edgewise appliance was bonded to available teeth. A soldered lingual arch wire was placed in the lower arch to conserve anchorage. Light continuous wires were placed progressing from 0.016 NiTi, 0.018 NiTi, 16×22 NiTi and finally 17×25 SS wire. Sufficient space was created for alignment of impacted permanent teeth by compressing open coil springs.

The patient was then referred to oral surgeon for surgical exposure of the impacted teeth by the closed eruption technique.

Surgical management

The mucoperiosteal flap was raised along the gingival margin and the damage to the soft-tissue flap was deemed of utmost importance, in particular, the periosteum, which was handled with all possible care. Cortical bone was removed with 3 or 5 mm chisels from the alveolus. Only a sufficient portion of the tooth was exposed to allow for isolation and bonding of the bracket. The tooth was irrigated with sterile water and dried with the aspirator. An attachment was bonded to it directly with Transbond light cure composite resin and moisture insensitive primer (MIP), and the mucoperiosteal flap was then repositioned and sutured back over the crown with 3.0 black silk, leaving only a twisted wire passing through the mucosa to apply the orthodontic traction (figure 3). The wire protruding through the mucosa was cut to a suitable length and fashioned into a hook. It was thought advisable to give the patient a course of antibiotics postoperatively for 5 days. Sutures were removed 1 week later. There were no postoperative complications.

Figure 3.

Surgical exposure and placement of brackets on impacted 33, 34, 43 and 44.

Orthodontic forces were then applied to the attachment to move the impacted tooth into occlusion. In the lower arch, guided eruption of the buccally impacted canines and first molars was done by applying traction forces with the help of lingual arch (figure 4). After sufficient eruption of the impacted teeth occurred, NiTi overlay wires tied into the brackets. Later treatment was focused on finishing with a well-interdigitated posterior occlusion. The entire treatment was completed in 14 months. After debonding, upper and lower Hawley retainers were given.

Figure 4.

Treatment progress.

Outcome and follow-up

All the impacted teeth were properly aligned and the patient finished with a significantly improved functional and aesthetic result. Mild flaring of lower anteriors occurred with minimum effect on patient's soft tissue profile. The mandibular midline shift to right was reduced to less than 1 mm (figure 5). Post-treatment orthopantomogram (figure 6) revealed good bone support and the axial inclination of the disimpacted teeth.

Figure 5.

Post-treatment photographs.

Figure 6.

Post-treatment OPG.

Comparison of the skeletal and soft tissue findings before and after treatment is given in tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Comparison of cephalometric measurements before and after treatment

| Composite analysis | Standard | Pretreatment | Post-treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SNA | 82 | 80 | 80 |

| 2. SNB | 80 | 74 | 73 |

| 3. ANB | 02 | 6 | 7 |

| 4. Upper incisor-NA | 22 | 19 | 18 |

| 5. Upper incisor-NA | 4 mm | 3 mm | 2 mm |

| 6. Lower incisor-NB | 25 | 23 | 25 |

| 7. Lower incisor-NB | 4 mm | 7 mm | 8 mm |

| 8. Interincisal angle | 131 | 140 | 137 |

| 9. Upper incisor-SN | 103 | 93 | 89 |

| 10. GoGn-SN | 32 | 40 | 42 |

| 11. FMA | 25 | 43 | 43 |

| 12. IMPA | 90 | 87 | 93 |

| 13. FMIA | 65 | 50 | 44 |

| 14. Wits appraisal | 0–2 mm | 3 mm | 3 mm |

| 15. Jarabak ratio (%) | 52–55 | 57 | 57 |

Table 2.

Comparison of soft tissue findings pretreatment and post-treatment

| Measurement | Landmark | Standard | Pre-Rx | Post-Rx |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facial form | ||||

| Facial convexity angle | G-Sn-Pg’ | 12 | 19 | 16 |

| Maxillary prognathism | G-Sn(HP)* | 6 | -1 | 0 |

| Mandibular prognathism | G-Pg’(HP)* | 0 | -15 | -13 |

| Vertical height ratio | G-Sn/Sn-Me’(HP)† | 1 | 71/63 | 71/67 |

| Lip position and form | ||||

| Nasolabial angle | Cm-Sn-Ls | 102 | 95 | 103 |

| Upper lip protrusion | Ls to (Sn-pg’) | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| Lower lip protrusion | Li to (Sn-Pg’) | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Mentolabial sulcus | Si to (Li-Pg’) | 4 | 7 | 6 |

| Vertical lip-chin ratio | Sn-Stm/Stm-Me’(HP) | 0.5 | 19/43 | 20/47 |

| Maxillary incisor exposure | Stm-1 | 2 | 1 | 32 |

| Interlabial gap | Stm-Stm(HP) | 2 | 0 | 0 |

*(HP) refers to parallel to horizontal plane.

†(HP) refers to perpendicular to horizontal plane.

Discussion

Dental impaction has been reported to affect as much as 25–50% of the population.1 Third molars and maxillary canines are the most commonly impacted teeth.2 3 Other teeth may be impacted upon but, less frequently. Potential factors related to impaction include crowding, maxillary transverse deficiency and physical impediments such as odontomas or supernumerary teeth.4–6 Certain syndromes demonstrate higher incidence of impacted teeth.7 Age at the start of the treatment, palatal versus buccal positioning and the distance of the tooth from the occlusal plane are factors reported to increase treatment time and complexity.8 9

The common methods of uncovering impactions are

Excisional gingivectomy;

Apically repositioned flap technique and

Closed eruption technique.

The aesthetic and functional outcomes of these procedures, such as effects on gingival height, clinical crown length, width of attached gingiva, gingival scarring and relapse potential need to be critically assessed in order to identify the optimal method of uncovering labial impactions.10 The closed eruption technique is believed by some to be the best method of uncovering labially impacted teeth, especially if the tooth is located high above the mucogingival junction or deep in the alveolus, where an apically repositioned flap may be difficult or impossible to use successfully. With the closed eruption technique, the crown of the tooth is exposed, an attachment is fixed to it and the flap is sutured back over the crown. A wire or chain extends from attachment through the coronal part of the flap. Some clinicians believe that the closed eruption produces the best aesthetic and periodontal results.11 12

Open eruption provides better localisation of teeth compared with closed eruption, but, in the presence of multiple impactions closed eruption is deemed to be a better choice.12 In the present case since the impacted teeth were situated quite deep in alveolus, excisional gingivectomy could lead to removal of all attached gingival and result in alveolar mucosal attachment. Apically repositioned flap was not considered suitable since, the teeth were buccally placed and it could result in increased clinical crown length, gingival scarring, intrusive relapse and damaged periodontium.13 14

Multiple methods of applying eruptive force to the teeth can be utilised. Power thread provides light eruptive forces but has a high decay rate.15 After eruption of impacted teeth into mouth, NiTi overlays can be tied on to the main base archwire to maintain the rigidity of anchor units.16 These work well with one impaction per arch or one per quadrant. In this case, however, to increase anchorage potential, lingual arches were employed which not only provided rigidity but also favourable direction of traction for eruption of buccally impacted teeth.

Learning points.

Multiple impacted teeth without any associated systemic conditions or syndrome are not common.

Several surgical and orthodontic treatment options are available to disimpact impacted permanent teeth.

- The common methods of uncovering impactions are

- Excisional gingivectomy;

- Apically repositioned flap technique;

- Closed eruption technique.

The outcomes of these procedures, such as, effects on gingival height, clinical crown length, width of attached gingiva, gingival scarring and relapse potential need to be critically assessed in order to identify the optimal method of uncovering buccal impactions.

Closed eruption technique has the best long-term prognosis.

With closed eruption technique teeth can be erupted through the bone maintaining the width of attached gingiva with good periodontal attachment and less chances of vertical relapse.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Andreasen JO, Pindborg JJ, Hjorting-Hansen E, et al. Oral health care: more than caries and periodontal disease. A survey of epidemiological studies on oral disease. Int Dent J 1986;36:207–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shroff B. Canine impaction diagnosis, treatment planning, and clinical management. In: Nanda R.ed. Biomechanics in clinical orthodontics. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1997:99–108 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishara SE. Clinical management of impacted maxillary canines. Semin Orthod 1998;4:87–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker A, Sharabi S, Chaushu S. Maxillary tooth size variation in dentitions with palatal canine displacement. Eur J Orthod 2002;24:313–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langberg BJ, Peck S. Adequacy of maxillary dental arch width in patients with palatally displaced canines. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000;118:220–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McConnell TL, Hoffmann DL, Forbes DP, et al. Maxillary canine impaction in patients with transverse maxillary deficiency. ASDC J Dent Child 1996;63:190–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley JF, Orlowski WA. Multiple osteomas, impacted teeth and odontomas—a case report of Gardner's Syndrome. J NJ Dent Assoc 1977;48:32–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart JA, Heo G, Glover KE, et al. Factors that relate to treatment duration for patients with palatally impacted maxillary canines. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2001;119:216–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becker A, Chaushu S. Success rate and duration of orthodontic treatment for adult patients with palatally impacted maxillary canines. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003;124:509–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vermette ME, Kokich VG, Kennedy DB. Uncovering labially impacted teeth: apically positioned flap and closed eruption techniques. Angle Orthod 1994;65:23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kokich VG, Mathews DP. Surgical and orthodontic management of impacted teeth. Dent Clin N Am 1993;37:181–204 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alling CC, Catone GA. Management of impacted teeth. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993;51:3–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohman I, Ohman A. The eruption tendency and changes of direction of impacted teeth following surgical exposure. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1980;49:383–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd RL. Clinical assessment of injuries in orthodontic movement of impacted teeth II: surgical recommendations. Am J Orthod 1984;86:407–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burstone CJ. Variable-modulus orthodontics. Am J Orthod 1981;80:1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braun S, Sjursen RC, Jr, Legan HL. Variable modulus orthodontics advanced through an auxiliary archwire attachment. Angle Orthod 1997;67:219–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]