Abstract

Angina bullosa haemorrhagica is the term used to describe benign subepithelial oral mucosal blisters filled with blood that are not attributable to a systemic disorder or haemostatic defect. It is a very rare condition. Elderly patients are usually affected and lesions heal spontaneously without scarring. The pathogenesis is unknown, although it may be a multifactorial phenomenon. Trauma seems to be the major provoking factor and long-term use of steroid inhalers has also been implicated in the disease. We present a 50-year-old patient with angina bullosa haemorrhagica. Trauma by sharp cusp of adjacent tooth and metal crown were identified as aetiological factors in this case. Lesions healed after removal of the metal crown and rounding of the cusp. Therefore, recognition of the lesion is of great importance to dentists, to avoid misdiagnosis.

Background

In 1967, Badham coined a new term, angina bullosa haemorrhagica (ABH), to describe oral blood-filled vesicles or bullae that could not be attributed to a blood dyscrasia, vesiculobullous disorders, systemic disease or other known causes.1 It is a disorder characterised by the acute formation of a blood-filled blister in the oral and oropharyngeal mucosa. Lesions of ABH occur mainly on the soft palate. Elderly patients are usually affected.

ABH is more common than previously suggested, and during the past decade, several studies have been published. In 1933, Balina of Argentina had already described the same lesions under the term traumatic oral haemophlyctenosis He also postulated a trauma-induced origin, especially in patients with senile capillary changes. In 1969, 14 patients were presented, and in 1976, the clinical and histological features were detailed and documented.2 This entity was then named recurrent oral hemophlyctenosis (ROH). As Kirtschig and Happle pointed out, the term ABH is misleading because most bullae arise in the oral cavity and are not consistent with lesions usually called ‘angina’; they proposed a more appropriate name for the disease: stomatopompholyx haemorrhagica. The authors believe that Balina was the first to describe this condition and suggested the use of the name ROH.3 The aim of this article is to report a new case of ABH, in an attempt to distinguish it from other blood containing bullae of the oral mucosa and to describe its management.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old female patient (figure 1) came to the department of oral medicine and radiology with a chief complaint of recurrent oral blisters on the right buccal mucosa recorded in a span of 15 days. Pain and a burning sensation was also present in that region. In the intraoral hard tissue examination, there was generalised attrition. A metal crown was present in relation to 17, 18, which were tender on percussion and were grade I mobile. Sharp cusps were present in relation to 16, 17, 18, 46, 47 and 48.

Figure 1.

Extraoral photograph of the patient.

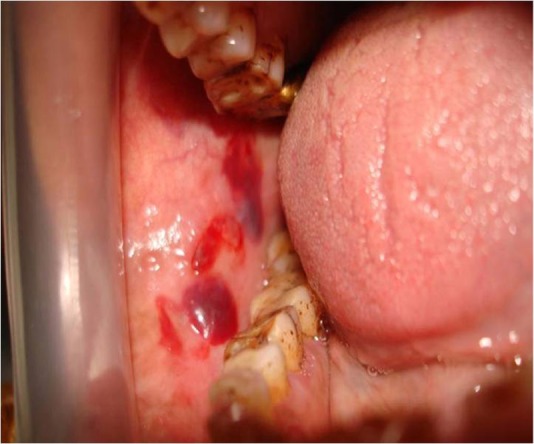

In the soft tissue examination, the gingiva was inflamed and three blood-filled bullae were present on the right buccal mucosa measuring approximately 3 ×3 mm, which were smooth surfaced, red in colour and whose surrounding area was erythematous (figure 2). On palpation, they were tender and bleed on manipulation. The patient reported no blood dyscrasias, anticoagulant therapy or liver disease and was generally having good health. Other than these oral blood blisters, the patient reported no oral conditions and no skin or eye lesions. Family history was also negative. Biopsy was advised, but the patient was not willing.

Figure 2.

Intraoral pretreatment photograph.

Investigations

The patient reported no blood dyscrasias, anticoagulant therapy or liver disease and was generally having good health. Other than these oral blood blisters, the patient reported no oral conditions and no skin or eye lesions. Family history was also negative. Biopsy was advised, but the patient was not willing.

Differential diagnosis

So, based on a history of continuous trauma from the teeth to the mucosa and clinical examination, we came to a provisional diagnosis of ABH. Differential diagnosis was made to exclude other mucosal or cutaneous diseases such as erythema multiforme, bullous lichen planus, pemphigus, pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa. Haematological blood cell count and differential and prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time) tests were carried out and the findings were within normal limits.

Treatment

In treatment removal of the metal crown and grinding of the sharp cusps were carried out. Ointment mucopain (benzocain 20%) and tantum oral rinse (benzydamine hydrochloride) were prescribed and the patient was recalled after 10 days.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient returned after 10 days and the lesion was healed (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Intraoral post-treatment photograph.

Discussion

ABH, first described by Badham in 1967, is a condition characterised by the rapid formation of a blood-filled blister on the oral mucosa.1 The disorder is now considered to be more common than the literature or conventional wisdom previously suggested. ABH mainly affects the soft palate, but lesions can also develop on other oral sites including the buccal mucosa, lip and the lateral surface of the tongue; the masticatory mucosa of the hard palate and gingiva does not seem to be affected. ABH patients have been mainly the middle-aged and elderly; lesions have not been documented in children less than 10 years of age. There is no apparent gender predilection.4

ABH has been considered as an idiopathic condition. The onset is sudden and minor mucosal insults may be involved in the pathogenesis. It may also follow trauma caused by eating, hot drinks, dental procedures or shouting. It is also noteworthy that mastication significantly increases the blood flow rate in the soft palate via parasympathetic reflex vasodilatation, and hard or crispy may injure the palate, which leads to ABH.5 The use of steroid inhalers in asthmatic patients is a possible aetiological factor. In the largest published series of 30 patients, no precipitating factor was found in 47%.6 Hosain and colleagues reported a case of postoperative ABH caused by intubation and extubation, describing a patient with a single blister at the junction of the soft and hard palate, which did not compromise the patient's airway. Lesions predominantly occur on the soft palate. The intact bulla is red to purple in colour. Blisters usually reach 2–3 cm in diameter and burst spontaneously, leaving ragged ulcers that heal without scarring. Clinically, the lesions may recur.7

The diagnosis of ABH is largely clinical, and includes the elimination of other disease processes at histology. The histopathological features of ABH include the parakeratotic epithelium with a subepithelial separation from the underlying lamina propria. Superficially located vesicles filled with erythrocytes and fibrin are seen. The inflammatory cell infiltrate, when present, consists primarily of lymphocytes. Neutrophils and eosinophils seen in other blistering disorders are not present. Immunofluorescence demonstrates no evidence of IgG, IgM, IgA or C3 antibodies within the epithelium or the basement membrane zone.8

Lesions of ABH can be easily confused with those occurring in many dermatological and systemic disorders. Even if there is a typical history of rapid blistering, the absence of any dermatological, haematological or systemic sign and normal healing of the ulcers generally lead to a diagnosis of ABH. Patients with bleeding disorders (thrombocytopenia and von Willebrand's disease) can present with intraoral blood-filled lesions but a haemostatic function test will distinguish between these conditions.9

The absence of desquamative gingivitis and nasal or conjunctival mucosal involvement will differentiate it from benign mucous membrane pemphigoid.10 Linear IgA disease and dermatitis herpetiformis usually can be differentiated by the presence of a pruritic rash. In oral bullous lichen, planus bullae are often associated with a striated pattern. The target-like lesion of the skin in erythema multiforme helps to distinguish it.11 The haemorrhagic bullae found in amylodosis are usually persistent and other clinical features include macroglossia and petechiae.12 Epidermolysis bullosa can be differentiated by the presence of bullous skin lesions.

The management of a patient presenting with oral blood-filled bullae should start with a detailed medical history and careful examination to differentiate ABH from other more serious diseases. The lesion should be biopsied to perform histology and direct immunofluorescence in order to exclude more serious diseases. A complete blood count and baseline coagulation tests should always be performed to exclude blood disorders. The patient should be reassured of the benign nature of the blisters. A large palatal or pharyngeal blister causing a choking sensation should be surgically treated if still intact. Management of these lesions should be symptomatic. Long-term follow-up is recommended to positively exclude other conditions which may present with oral blood containing bullae.

Learning points.

The diagnosis is difficult in patients as angina bullosa haemorrhagica is asymptomatic and heals spontaneously without scarring and its rare appearance.

The diagnosis of the lesion is very important as a rapidly expanding blood-filled bulla in the oropharynx can cause upper airway obstruction.

Therefore, a high level of suspicion is warranted on the part of the dentists who may be the first to encounter the lesion.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Giuliani M, Favia GF, Miani CM. Angina bullosa haemorrhagica: presentation of eight new cases and a review of the literature. Oral Dis 2002;8:54–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grinspan D. Hemoflictenosis bucal recidivante. In: Enfermedades de la boca. Vol III Buenos Aires: Mundi Philippe Sionneau, 1976:1502–5 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grinspan D. Angina bullosa haemorrhagica. Int J Dermatol 1999;38:525–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamamoto K, Fujimoto M, Inoue M, et al. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica of soft palate: report of 11 cases and litreture review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006;64:1433–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horie N, Kawano R, Inaba J, et al. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica of soft palate: a clinical study of 16 cases. J Oral Sci 2008;50:33–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stephenson P, Lamey P-J, Scully C, et al. Angina bullosa haemorrhagica: a report of three cases and review of the litreture. Clin Exp Dermatol 1990;15:422–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pahl C, Yarrow S, Steventon N, et al. Angina bullosa haemorrhagica presenting as acute upper airway obstruction. Br J Anaesth 2004;92:283–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curran AE, Rives RW. Angina bullosa haemorrhagica: an unusual problem following periodontal yherapy. J Periodontol 2000;71:1770–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korman N. Bullous pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;16:907–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, et al. Oral & maxillofacial pathology. 2nd edn St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsiever, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonçalves LM, Bezerra Júnior JR, Cruz MC. Clinical evaluation of oral lesions associated with dermatologic diseases. An Bras Dermatol 2010;85:150–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz HC, Olson DJ. Amyloidosis: a rational approach to diagnosis by intraoral biopsy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1975;39:837–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]