Abstract

This is a case of acute splenic and bilateral renal infarction in a patient with non-small cell lung carcinoma during chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin. Till date, bilateral renal infarction following gemcitabine and cisplatin has been reported only once in the past. The case that is being reported has had acute splenic and bilateral renal infarct and has not been reported previously. Splenic and renal infarction should be considered in the differential diagnosis of excruciating abdominal pain and backache in a patient on gemcitabine-based and cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Background

Cancer is a hypercoagulable state and was first noted by Trousseau1 in 1865. Thrombosis and thromboembolism in cancer patients are multifactorial involving both local factors (endothelial lesions) and systemic factors (coagulation abnormalities). Proliferating and degenerating tumour cells release tumour necrosis factors and interleukins which are potent activators of coagulation cascade. Besides, epithelial damage has purportedly a major role in chemotherapy-induced vascular events. Cisplatin is known to induce vasospasm that may lead to vascular abnormalities such as Raynaud's phenomenon and systemic hypertension or less commonly angina, myocardial infarction and mesenteric ischaemia. Cisplatin can also cause vasospasm of intracranial vessels producing a cereberovascular stroke.2–4 This is a first case report of acute splenic and bilateral renal infarction in a patient with non-small cell lung carcinoma during chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin. Splenic and renal infarction should be considered in the differential diagnosis of excruciating abdominal pain and backache in a patient on gemcitabine-based and cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Case presentation

A 59-year-old male patient was diagnosed as a metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with squamous histology. He was started on gemcitabine and cisplatin doublet-based palliative chemotherapy. On day 7 of his cycle he presented with sudden onset excruciating abdominal pain and backache that was not relieved with common analgesics like paracetamol and tramadol. General physical examination failed to elicit the cause of pain. He required heavy doses of opioid analgesia for pain control.

Investigations

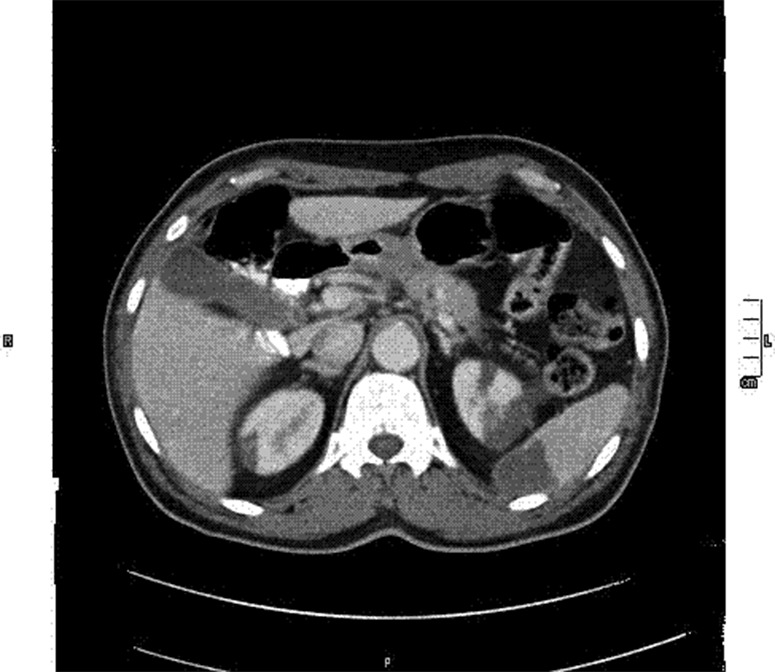

A contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen was performed to find out the cause of pain which revealed, quite unexpectedly wedge shape hypodensities in spleen and bilateral kidneys, likely representing infarcts (figure 1). Basic blood work and advanced coagulation profile were ordered to see for any existence of a reversible hyper coagulation state. Laboratory analyses revealed normal hematological and biochemical parameters, lactate dehydrogenase, 2150 U/l (normal 313–618); urinalysis showed no erythrocytes and/or any leucocytes /high power field. Tests for anticardiolipin antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (both c-ANCA and p-ANCA), anti-nuclear antibody and anti-dsDNA were all negative. Screening test for lupus anticoagulant was 31s (normal 24.4–32.2). Coagulation tests provided the following results: Coomb's test (direct and indirect)—negative, anticardiolipin antibody (both IgG and IgM)—negative; protein C activity, 79.80% (normal 70–140%); and protein S activity, 44% (normal 60–140%); normal IgM and IgG β2 glycoprotein and; anti-thrombin III activity, 113.88% (normal 75–125%); other laboratory parameters were within normal ranges. Echocardiography did not reveal any valvular or thrombotic pathology of the heart. The electrocardiogram showed a normal sinus rhythm. He was diagnosed as having splenic and bilateral renal infarction and therapy with aspirin (150 mg/day) was begun. Gemcitabine and cisplatin were discontinued. In view of disease aggressiveness and extensiveness, and paucity of data related to continuation of same chemotherapy, his chemo plan was modified to single-agent docetaxel-based palliative chemotherapy. The patient was followed up with CT scanning of chest and abdomen after three doses of docetaxel. Disease in the chest was stable. Abdominal scan revealed infarction areas healed with scarring (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Splenic and bilateral renal infarcts.

Figure 2.

Healing scars of splenic and renal infarct.

Treatment

Managed with opioid analgesics, aspirin as antiplatelet drug and change of chemotherapy to single-agent docetaxel in subsequent chemotherapy cycles.

Outcome and follow-up

The infarcts healed with scarring. Patient is still continuing on chemotherapy.

Discussion

The mechanisms of vascular events in cancer patients are largely unknown. Drug-induced endovascular damage, platelet activation, an abnormality of thromboxane-prostacyclin homeostasis, hypomagnesaemia-related arterial constriction and endothelial damage are some of the putative mechanisms of these vascular events.

Despite being common occurrence, reporting of vascular events is not at par with its occurrence. Though bilateral renal infarction has been reported by Cavdar et al5 in 2007, this appears to be the first case that reports splenic and bilateral renal infarction in a lung cancer patient treated with gemcitabine and cisplatin. The same disease diagnosis, the same chemotherapy agents in combination and similar presenting complaints point towards a more serious hitherto less discussed and less documented serious complication of this doublet chemotherapy. Splenic and renal infarction should be considered in the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain and backache in a lung cancer patient being treated with gemcitabine and cisplatin.

The most common causes of splenic infarct are bacterial endocarditis, sickle cell disease and haematological malignancies.6 The most common causes of renal infarction are renal artery embolism secondary to mitral stenosis, vegetations in bacterial endocarditis, atrial fibrillation, thrombus in the left ventricle and recent myocardial infarction.7–9

In this case, classical causes of splenic and renal infarction were excluded by exhaustive laboratory analysis and other investigations. Literature search revealed both gemcitabine and cisplatin in isolation to be the causative agents for thrombotic/thromboembolic events. With these best efforts, we could lay our hands upon only one similar case report by Cavdar et al. Similar to that, we suspected that the cause of splenic and renal infarction was antineoplastic agents.

Gemcitabine and cisplatin are usually administered in combination to treat a variety of malignancies, such as in the treatment of non-small cell lung carcinoma.10 11 This doublet-based combination treatment may induce vascular events. It has been shown that cisplatin increases platelet reactivity.12 Gemcitabine has been demonstrated to cause immune-mediated side effects.13

Acute splenic and renal infarction may manifest clinically as a pain similar to renal colic, and is often misdiagnosed as an acute pyelonephritis or renal colic because of similar presenting symptoms, as shown in the present case. An elevated serum lactate-dehydrogenase with little or no rise in serum aminotransferases is strongly suggestive of renal infarction, as seen in the present case.7 8 The radiological findings of the presented case were compatible with splenic and multiple segmental renal infarctions. The diagnosis was confirmed by follow-up imaging, as the hypodense areas on CT at the time of diagnosis were seen to heal with scarring on follow-up images 2 months after the initial diagnosis (figure 2).

In conclusion, the use of gemcitabine and cisplatin should be considered as a cause of splenic and renal infarction in patients being treated with this doublet chemotherapy. Furthermore, visceral infarction should be considered in the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain and backache in a lung cancer patient treated with gemcitabine and cisplatin.

Learning points.

Chemotherapeutic agents are frequently associated with vascular events.

Platinums as chemotherapy agents are frequently associated with vascular events, which go unnoticed or undiagnosed.

Chemotherapy-induced vasculitis should be kept in the differential diagnosis of any unexplained symptom/development in a cancer patient on chemotherapy.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Trousseau A. Phlegmasia alba dolens. In: Clinique Medicale de l'Hotel Dieu de Paris. Paris: Balliere, 1865:654–712 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doll DC, Yarbro JW. Vascular toxicity associated with antineoplastic agents. Semin Oncol 1992;19:590–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Icli F, Karaoguz H, Dincol D, et al. severe vascular toxicity associated with cisplatin based chemotherapy. Cancer 1993;72:587–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger CC, Bokemeyer C, Schneider M, et al. Secondary Raynaud's phenomenon and other late vascular complications following chemotherapy for testicular cancer. Eur J Cancer 1995;31A(–):2229–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavdar C, Toprak O, Oztop I, et al. Bilateral renal infarction in a patient with lung carcinoma treated with cisplatin and gemcitabine. Renal Failure 2007;29:923–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osler W. The principles and practice of medicine. 4th edn New York: D Appleton and Company, 1901 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu PL, Wei YF, Huang JW, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with segmental renal infarction. Nephrology 2006;11:336–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korzets Z, Plotkin E, Bernheim J, et al. The clinical spectrum of acute renal infarction. Isr Med Assoc J 2002;4:781–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolderman R, Oyen R, Verrijcken A, et al. Idiopathic renal infarction. Am J Med 2006;119:9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Artal-Cortes A, Martinez-Trufero J, Herrero A, et al. Increasing-dose gemcitabine plus low-dose cisplatin in metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer. Anticancer Drugs 2003;14:111–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metro G, Cappuzzo F, Finocchiaro G, et al. Development of gemcitabine in non-small cell lung cancer The Italian contribution. Ann Oncol 2006;17:S37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Togna GI, Togna AR, Franconi M, et al. Cisplatin triggers platelet activation. Thromb Res 2000;99:503–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Numico G, Garrone O, Dongiovanni V, et al. Prospective evaluation of major vascular events in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma treated with cisplatin and gemcitabine. Cancer 2005;103:994–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]