Abstract

We present a case of an 18-year-old Caucasian man with a rare autosomal recessive disorder called autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy (APECED). This patient had manifestations of all clinical components of this multisystemic disease which included intestinal failure secondary to autoimmune enteropathy. We present a unique multidisciplinary management for this genetic condition. Although patients with APECED do not always have all the disease components (a total of eight exist), the majority have at least 3–5 components. This excludes the psychosexual implications which are often ignored. This case highlights the importance of (1) management of APECED in a multidisciplinary nature that includes a gastroenterologist, immunologist, endocrinologist, dietitians, etc and the (2) management of intestinal failure component of APECED is best suited in a specialist intestinal failure unit where expertise is available for complex malabsorption disorders.

Background

Although a rare condition, this case demonstrates that the successful management of complex multiorgan diseases should only come from multidisciplinary inputs. Furthermore, the management of individual organ components can also benefit from multidisciplinary care such as involvement of the intestinal failure team management of this patient's enteropathy. Also, this case demonstrates the diagnostic challenges of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) as although the patient was being treated for hepatitis for 16 years, a diagnosis was only established at the age of 18. This could be explained by the delayed presentation of phenotypic features in APECED.

Case presentation

An 18-year-old Caucasian man with a 16-year history of autoimmune hepatitis, portal hypertension and autoimmune polyendocrinopathy was referred to our gastroenterology clinic with non-bloody diarrhoea, abdominal bloating and failure to gain weight over 3 years. He was on tacrolimus 2 mg twice daily and prednisolone 3 mg daily for his hepatitis. Clinical examination revealed a body mass index of 15 kg/m2, dystrophic nails (figure 1) with leuconychia and clubbing, poor dentition (figure 2), oral thrush and a distended non-tender abdomen. The patient had not consumed alcohol.

Figure 1.

Nail illustrating candida infection. All other nails were affected.

Figure 2.

Image illustrates poor dentition, which is likely to be a result of demineralisation. Oral health was also affected by chronic candidiasis infection.

Investigations

Serum studies: sodium 145 mmol/l (reference 133–146), potassium 2.5 mmol/l (3.5–5.3), urea 1.3 mmol/l (2.5–7.8), creatinine 50 μmol/l (64–104), calcium 1.56 mmol/l (2.20–2.60), magnesium 0.56 mmol/l (0.70–1.00), phosphate 0.69 mmol/l (0.80–1.50), albumin 37 g/l (35–50), alanine aminotransferase 149 IU/l (<55), alkaline phosphatase 645 IU/l (100–320), bilirubin 30 μmol/l (2–21) and anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody was negative.

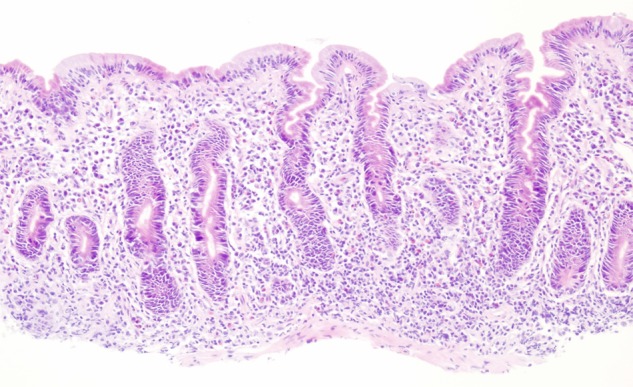

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy demonstrated no obvious abnormalities. Duodenal histology revealed complete villous atrophy as well as total goblet cell and endocrine cell depletion. Expansion of the lamina propria due to inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils) and an increased number of intraepithelial lymphocytes were noted (figure 3). An increased number of apoptotic bodies were seen at the crypt base. There were no infectious organisms.

Figure 3.

Duodenal biopsy. Histology shows subtotal to total villous atrophy, increased cellularity in the lamina propria due to lymphoplasmacellular infiltrates, increased number of intraepithelial lymphocytes, loss of goblet cells, Paneth cells and endocrine cells. An increased number of mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies at the crypt base were noted.

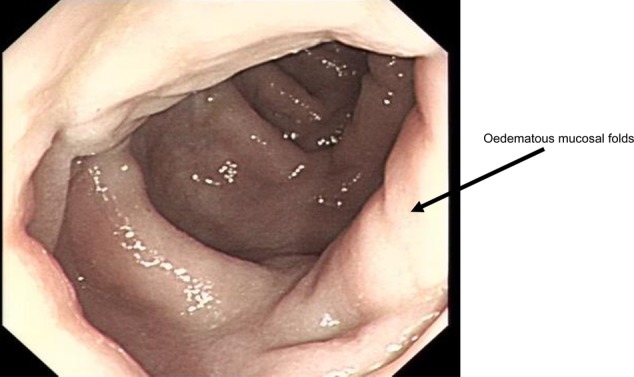

Colonoscopy revealed oedematous folds throughout most of the colon (figure 4). Histology demonstrated complete loss of goblet cells, with many apoptotic bodies at the crypt base, an increased epithelial mitotic activity and chronic inflammatory cells in the lamina propria (figure 5).

Figure 4.

An endoscopic view of the descending colon illustrating oedematous folds throughout most of the colon.

Figure 5.

Colonic biopsy. Histology shows increased cellularity in the lamina propria predominantly due to lymphoplasmacellular infiltrates as well as complete depletion of goblet cells and endocrine cells. An increased number of mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies at the crypt base were noted.

The histology from endoscopic biopsy showed autoimmune enteropathy. Based on the histology and the clinical picture, a diagnosis of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy, also known as autoimmune polyglandular type 1 syndrome, was made. This was confirmed on genetic screening.

Other tests

Full endocrine screen: Parathyroid function tests were normal. Adrenocortical and gonadal hormonal tests demonstrated adrenocortical and gonadal insufficiency, respectively.

Differential diagnosis

APECED is also known as autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 (APS-1). APS types 2 and 3 may present similarly. In APS-2, patients are affected with Addison's disease and autoimmune thyroid disease and/or insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (Schmidt's syndrome), but no hypoparathyroidism or candidiasis.1 APS-3 is represented by patients with autoimmune thyroid disease plus one or more other autoimmune disorders, but no Addison's disease.1

Treatment

The management for our patient was multidisciplinary. This included the intestinal failure team, a hepatologist, endocrinologist, immunologist and microbiologist. The acute intestinal failure component was managed in a tertiary hospital with an intestinal failure specialist. Safe electrolyte replacement and parenteral nutrition were commenced. The patient was commenced on intravenous fluconazole for oral candidiasis. He required high doses of intravenous steroids for the autoimmune component, which had caused autoimmune hepatitis and autoimmune enteropathy. He received rituximab, a monoclonal antibody against CD-20, to control the autoimmune activity. From an endocrine point of view, he received specialist care which included adrenocortical and gonadal hormone replacement.

Outcome and follow-up

Twelve months after commencement of nutritional support and rituximab (immunosuppressive therapy), the patient is no longer malnourished and has a normal body mass index. His autoimmune disease activity is under control. However, he still requires home parenteral nutrition. He remains under follow-up by dietitians, gastroenterologists and immunologists.

The patient remains on lifelong hormonal therapy for adrenal and gonadal insufficiency and, therefore, lifelong endocrinology care. Improved dentition reflects improved nutritional status and, therefore, enamel mineralisation.

Discussion

APECED (APS type 1) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder. A monogenic mutation of AIRE (autoimmune regulator, located on chromosome 21), is the likely pathogenic paradigm for APECED.2 Genetic screening has confirmed single gene AIRE mutation. APECED is rare, but it appears most frequently in Finns, Sardinians and Iranian Jews.3–5 The prevalence of APECED in Finland has been estimated to be 1 case per 25 000.3 Known frequencies in other ethnic groups include 1 case per 14 400 in Sardinians and 1 case per 9000 in Iranian Jews.4 5

APECED is diagnosed by the presence of at least two of three major component diseases: chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (usually presents first), primary hypoparathyroidism and autoimmune adrenal insufficiency (usually presents last—after the first decade of life).6 7 APECED usually presents in infants aged 3–5 years old, but this is variable. It has been reported that the complete triad was present only in 50% of patients at the age of 20, 55% at age 30 and 40% at age 40.8

APECED is diagnosed clinically, prompting a myriad of investigations for confirmation. These include full blood count, urea and electrolytes, calcium, parathyroid hormone, liver function tests, blood glucose, synacthen test, thyroid function tests, testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinising hormone in males.

More specialised tests include serum autoantibody screen, which may include autoantibodies to 21-hydroxylase, 17-hydroxylase, thyroid peroxidase and thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins, glutamic acid decarboxylase and islet cell antibodies, and parietal cell enzyme (H+/K+ -ATPase) antibodies.9 10 The absence of these autoantibodies does not exclude APECED.

Other investigations depend on the presentation of the disease. They may include endoscopy and biopsies (as in our case). Coeliac disease and atrophic gastritis can be ruled out here.

Ahonen et al7 described a Finnish case series of 68 patients highlighting the broad clinical spectrum of APECED. Their study concluded that the majority of patients have 3–5 manifestations presenting at different stages in life.

Weiler et al11 reported a 28-year-old woman who presented at age 5 with nail candidiasis and blurred vision. She later developed hypoparathyroidism and, finally, adrenal insufficiency. This patient also suffered with chronic diarrhoea.

Because APECED is so rare, there are a relatively small number of case reports in the literature. The reports and studies available highlight the variability of this syndrome. Apart from the classic 3 manifestations, a whole host of other pathologies have been reported. These include autoimmune hepatitis12 (as in our case report), autoimmune thyroid disease,13 hypogonadotropic hypogonadism,14 type 1 diabetes mellitus,15 pituitary failure,16 atrophic gastritis and pernicious anaemia,5 13 intestinal malabsorption12 (our case), tubulointerstitial nephritis,17 pulmonary disease18 19 and other manifestations.

The treatment of this condition is therefore best managed in the multidisciplinary setting for optimal patient care.

Learning points.

Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) is a true multisystemic disorder which is best managed through a multidisciplinary team.

Intestinal failure component is best managed in a unit which provides expert multidisciplinary team intestinal failure care.

Clinicians should have an awareness of the disorder as the clinical spectrum in patients with APECED is broad. Phenotypic presentation of disease components may not be obvious or may be delayed and therefore lifelong follow-up is required for their detection.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Neufeld M, Maclaren NK, Blizzard RM. Two types of autoimmune Addison's disease associated with different polyglandular autoimmune (PGA) syndromes. Medicine 1981;60:355–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Org T, Chignola F, Hetenyi C, et al. The autoimmune regulator PHD finger binds to non-methylated histone H3K4 to activate gene expression. EMBO Rep 2008;9:370–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjorses P, Halonen M, Palvimo JJ, et al. Mutations in the AIRE gene: effects on subcellular location and transactivation function of the autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy protein. Am J Hum Genet 2000;66:378–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosatelli MC, Meloni A, Meloni A, et al. A common mutation in Sardinian autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy patients. Hum Genet 1998;103:428–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zlotogora J, Shapiro MS. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type I among Iranian Jews. J Med Genet 1992;29:824–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neufeld MB, Blizzard RM. Polyglandular autoimmune diseases. In: Pinchera A, Doniach D, Fenzi GF, Baschieri L, eds. Symposium on autoimmune aspects of endocrine disorders. New York: Academic Press, 1980:357–65 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahonen P, Myllarniemi S, Sipila I, et al. Clinical variation of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) in a series of 68 patients. N Engl J Med 1990;322:1829–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perheentupa J. APS-I/APECED: the clinical disease and therapy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2002;31:295–320, vi [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meloni A, Furcas M, Cetani F, et al. Autoantibodies against type I interferons as an additional diagnostic criterion for autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:4389–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oftedal BE, Wolff AS, Bratland E, et al. Radioimmunoassay for autoantibodies against interferon omega; its use in the diagnosis of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I. Clin Immunol 2008;129:163–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiler FG, Dias-da-Silva MR, Lazaretti-Castro M. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1: case report and review of literature. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 2012;56:54–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betterle C, Greggio NA, Volpato M. Clinical review 93: autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:1049–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perheentupa J. Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:2843–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soderbergh A, Myhre AG, Ekwall Oet al. Prevalence and clinical associations of 10 defined autoantibodies in autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:557–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halonen M, Eskelin P, Myhre AGet al. AIRE mutations and human leukocyte antigen genotypes as determinants of the autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:2568–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward L, Paquette J, Seidman Eet al. Severe autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy in an adolescent girl with a novel AIRE mutation: response to immunosuppressive therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:844–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ulinski T, Perrin L, Morris Met al. Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy syndrome with renal failure: impact of posttransplant immunosuppression on disease activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:192–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Hernández FJ, Ocaña-Medina C, González-León R, et al. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2006;27:657–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alimohammadi M, Dubois N, Skoldberg Fet al. Pulmonary autoimmunity as a feature of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 and identification of KCNRG as a bronchial autoantigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:4396–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]