Abstract

Keratocystic odontogenic tumours are known for their peculiar behaviour, varied origin, debated development, unique tendency to recur and disputed treatment modalities. Thus, it has been the subject of much research over the last 40 years. It was formerly known as odontogenic keratocyst (OKC). OKC received its new title as keratocystic odontogenic tumour (KCOT) by the WHO (2005) in order to suggest its aggressive and recurrent nature. KCOT is a benign intraosseous neoplasm of the jaw. Involvement of the maxillary sinus is an unusual presentation. We present the case of an 11-year-old child with extensive KCOT and an impacted canine in the right maxillary sinus. The cyst was initially misdiagnosed to be a dentigerous cyst based on the clinical and radiographic features though a differential diagnosis of KCOT and adenomatoid odontogenic tumour was made. The histological examination of the specimen finally confirmed it to be a KCOT. The clinical, radiological and histological features of this tumour along with its surgical management have been discussed.

Background

A keratocystic odontogenic tumour (KCOT) occurring in the maxillary sinus is very often misdiagnosed to be a dentigerous cyst. Cystic lesions should be examined cautiously to render appropriate treatment or else chances of recurrence of an aggressive lesion like the KCOT are high.

It also emphasises the importance of histopathological examination which is of utmost diagnostic value in these cases and without which we cannot draw any definite conclusion regarding the lesion.

Case presentation

An 11-year-old male child reported to our clinic with a chief complaint of an asymptomatic hard swelling on the left side of the face since 3 months. He had no systemic illness and was non-syndromic. Extraoral examination revealed a hard swelling on the left side of the face; from the ala of the nose to the corner of the lips. Intraoral examination revealed a diffuse hard swelling of 4×3×2.2 cm in diameter in the buccal vestibule extending from the mesial aspect of lateral incisor to the permanent first molar region (figure 1). The swelling was firm and hard in consistency.

Figure 1.

Intraoral view of the lesion.

Investigations

Aspiration yielded a yellowish straw-coloured fluid which was consistent with the diagnosis of a cystic lesion. Routine laboratory parameters were normal.

Panoramic radiograph revealed a dislocated unerupted maxillary left permanent canine with a well-defined radiolucent lesion adjoining the tooth was detected. The maxillary left first and second premolars were missing (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Orthopantomograph showing the extent of the lesion with involvement of the maxillary sinus.

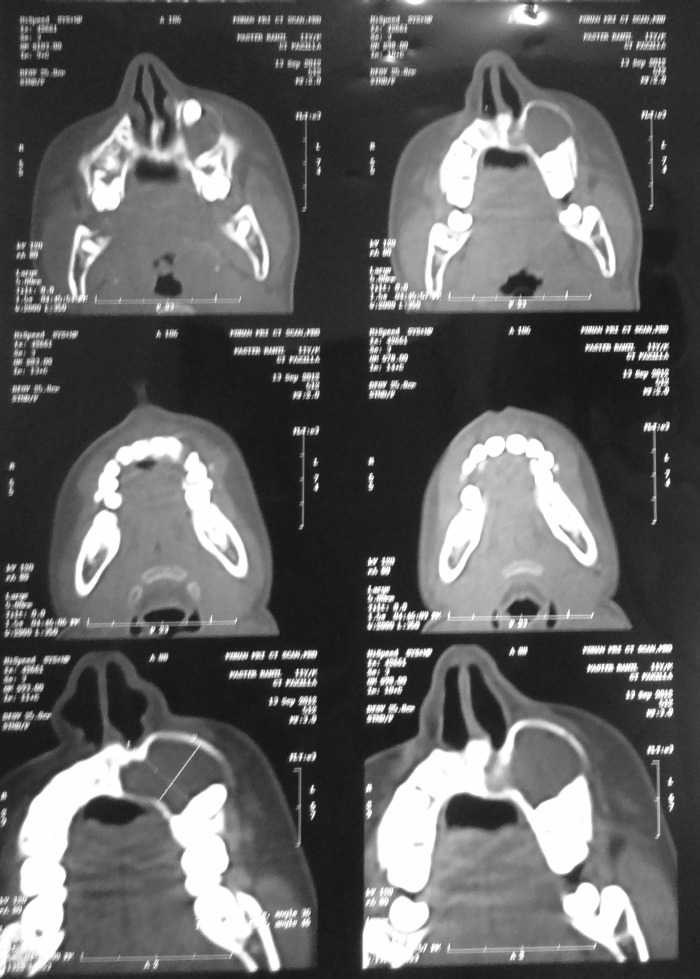

In order to determine the exact location of the canine tooth, maxillary occlusal radiograph and CT was performed with paranasal inspection. In the axial cross section, a radio-opaque image of the tooth and a radiolucent image of the cyst attached to the tooth were seen. Based on clinical and radiological examination, a provisional diagnosis of dentigerous cyst was made (figure 3).

Figure 3.

CT showing the extent and borders of the keratocystic odontogenic tumour.

Blood investigations were advised which revealed normal values.

Histopathological examination with H&E-stained section revealed the presence of epithelium overlying connective tissue stroma. The epithelium was found to be parakeratinised stratified squamous in nature with 4–10 cell layers in thickness. It showed presence of surface corrugation, tall columnar cells with hyperchromatic nucleus in basal layer arranged in palisaded row-like appearance. The connective tissue was found to be fibrocellular in nature with loose collagen fibres, spindle-shaped fibroblasts, mild infiltration of chronic inflammatory cells predominantly lymphocytes and plasma cells and extravasated red blood cells (figure 4).

Figure 4.

H&E stained section of the lesion.

The overall histopathological findings were suggestive of keratocystic odontogenic tumour.

Differential diagnosis

The lesion was suspected primarily to be a dentigerous cyst based on the clinical and radiographic presentation of the lesion. Apart from that, KCOT and adenomatoid odontogenic tumour (AOT) were suspected.

Dentigerous cyst: As in the case of a dentigerous cyst, the lesion was clinically a painless, hard swelling resulting in facial asymmetry. Also radiographically, it was found to be associated with an unerupted canine extending cranially into the maxillary sinus which is a typical finding regarding a dentigerous cyst. It was a unilocular radiolucent, expansile lesion with well-defined cortex and there was displacement of the unerupted tooth by the lesion. A straw-coloured fluid was derived from the lesion on aspiration. All these features indicated a dentigerous cyst.

KCOT: another differential diagnosis of the lesion was a KCOT. But the radiographic location of the lesion was found to be a rare occurrence in case of KCOT. Unlike the lesion here, in KCOT there is minimal or no expansion present. In KCOT, internal septa may be present within the radiolucent lesion which was not seen in this lesion. The presence of straw-coloured fluid aspirate is one indication towards a KCOT.

AOT occurs mostly in association with an unerupted maxillary canine. It exhibits a well-demarcated, smooth, almost always unilocular radiolucency that exhibits a smooth corticated border. Displacement of the teeth is seen frequently and encroachment of maxillary sinus is present. All these features corresponded to our case which was indicative of the lesion to be an AOT. But unlike in the present case, a clear fluid is derived from an AOT.

Treatment

Under all aseptic precautions in the operation theater, general anesthesia was given to the patient. Degloving incision was made 3–4 mm above the attached gingival (figure 5). Mucoperiosteal flap was raised and the cystic lining along with cystic contents and the associated unerupted maxillary canine was removed (figures 6 and 7). Then a cotton pledget dipped in Carnoy's solution was applied over the area for about 5 min for chemical cauterisation of the tissues. Betadine irrigation was performed and the borders of the wound were then sutured. The wound healed uneventfully.

Figure 5.

Degloving incision given above the attached gingiva.

Figure 6.

Mucoperiosteal flap being raised and exposing the lesion.

Figure 7.

Removal of the cyst along with the associated maxillary left canine.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient has been asymptomatic for 4 months after the operation. As the lesion has a high reccurence rate, so a follow-up period of atleast 5 years is necessary.

Discussion

The odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) is one of the most aggressive odontogenic cysts owing to its relatively high recurrence rate and its tendency to invade adjacent tissues.1–6 In 1967, Toller suggested that the OKC may best be regarded as a benign neoplasm rather than a conventional cyst based on its clinical behaviour.7

In the years since, published reports have influenced WHO to reclassify the lesion as a tumour. Several factors form the basis of this decision.

Behaviour: As described earlier, the OKC is locally destructive and highly recurrent.

Histopathology: Studies such as that by Ahlfors and others show the basal layer of the OKC (KCOT) budding into connective tissue. In addition, WHO notes that mitotic figures are frequently found in the suprabasal layers.

Genetics: PTCH (‘patched’), a tumour suppressor gene involved in both nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome and sporadic KCOTs, occursonchromosome 9q22.3-q31.36–40 normally, PTCH forms a receptor complex with the oncogene SMO (‘smoothened’) for the SHH (‘sonic hedgehog’) ligand. PTCH binding to SMO inhibits growth-signal transduction. SHH binding to PTCH releases this inhibition. If normal functioning of PTCH is lost, the proliferation-stimulating effects of SMO are permitted to predominate.8 9

Given these features, not observed in common cysts, such as radicular and dentigerous cysts, the WHO reclassified OKC as a KCOT in 2005.6 8 10 So we chose the term KCOT instead of OKC in this report.

KCOTs of maxilla have diagnostic difficulties owing to lack of specific clinical and radiographic characteristics. They are less common in maxilla than mandible with only 31.3% in maxilla. But when they do occur, they are more common in the canine region which was the case in our patient also. KCOT has been shown to have a bimodal age distribution with first peak in the second and third decades and the second peak in the fifth decade or later. It is said that the lesions in the second peak are more common in maxilla.1 4 But the present case does not follow this conventional norm regarding age and area specificity of the cyst.

The occurrence of KCOT in maxilla is relatively rare and more uncommon is its occurence in a 11-year-old child with invasion of the maxillary sinus that is again unusual, which was seen in this case. In the CT scan, the lesion appeared to be a large, well-defined, expansile, thin-walled cystic lesion extending cranially into the maxillary sinus.

Histologically KCOTs has been classified by some authors as parakeratotic or orthokeratotic subtypes. These types refer to the histologic characteristics of the lining and the type of keratin produced. Compared to the parakeratotic subtype, the orthokeratotic subtype produces keratin more closely resembling the normal keratin produced by the skin with a keratohyaline granular layer, immediately adjacent to the layers of keratin which do not contain nuclei. The parakeratotic subtype has more disordered production of keratin; no keratohyaline granules are present and cells slough into the keratin layer. The keratin contains nuclei and is referred to as parakeratin. The parakeratotic subtype is the most frequent (80%) and has a more aggressive clinical presentation than the orthokeratotic variant. Some pathologists think that the orthokeratotic type should be classified as a separate entity and termed as orthokeratotic odontogenic cyst because of its distinct histological feature and substantially less-aggressive behaviour. The lesion reported in this case is a parakeratotic KCOT.11

In conclusion, the most common impacted tooth in jaws is the third molar followed by the maxillary canine and the most common cyst associated with these impacted teeth is dentigerous cyst, encircling the neck of impacted tooth. Nevertheless, according to our reported case, in young adults, other than dentigerous cyst, KCOT should also be considered, since KCOT has features similar to those of both dentigerous cysts and AOT.12 The best way to diagnose KCOTs may be to combine accurate clinical, radiographic and trans-surgical observations with a biopsy specimen examination; this approach will help determine the most effective treatment, thereby preventing recurrences.

Learning points.

Since keratocystic odontogenic tumour (KCOT) has features similar to those of dentigerous cysts, which is a common provisional diagnosis for KCOT, the best way to diagnose KCOTs may be to combine accurate clinical, radiographic and trans-surgical observations with a biopsy specimen examination; this approach will help determine the most effective treatment, thereby preventing recurrences.

Because a parakeratinised KCOT can be associated with Gorlin-Goltz syndrome, the clinician should properly evaluate the presence of features of the syndrome which was found negative in this case.

The parakeratotic type of KCOT is more aggressive as can be judged by its generous amount of bone involvement and erosion of the sinus wall.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Veena KM, Rao R, Jagadishchandra H, et al. Odontogenic keratocyst looks can be deceptive, causing endodontic misdiagnosis. Case Rep Pathol 2011;2011:1–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nayak P, Nayak S. Recurrent odontogenic keratocyst of maxilla in a nine year old child—report of a case report. Indian J Dental Sci 2011;3:19–22 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwon HI, Lim WB, Kim JS, et al. Odontogenic keratocyst associated with an ectopic tooth in the maxillary sinus—a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Korean J Pathol 2011;45:S5–10 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motwani MB, Mishra SS, Anand RM, et al. Keratocystic odontogenic tumour:case reports and review literature. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol 2011;23:150–4 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali M, Baughman RA. Maxillary odontogenic keratocyst a common and serious clinical misdiagnosis. J Am Dent Assoc 2003;134:877–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh M, Gupta KC. Surgical treatment of odontogenic keratocyst by enucleation. Contemp Clin Dent 2010;1:263–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahadesh J, Kokila , Laxmidevi BL. Odontogenic keratocyst of maxilla involving the sinus-OKC to be a cyst or a tumour? J Dent Sci Res 2010;1:83–90 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hemavathy S, Roy S. Follicular odontogenic keratocyst mimicking dentigerous cyst-report of two cases. Arch Oral Sci Res 2011;1:100–3 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhary D, Bhargava M, Aggarwal S, et al. Keratocystic odontogenic tumour—a case report with review of literature. Indian J Stomatol 2012;3:66–9 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murthy RTK, Reddy SBH, Kumar H, et al. Keratocystic odontogenic tumour of thr maxilla-a serious entity often misdiagnosed: a report of two cases resembling dentigerous cysts. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol 2011;23:S412–15 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cakur B, Miloglu O, Yolcu U, et al. Keratocystic odontogenic tumour invading the right maxillary sinus: a case report. J Oral Sci 2008;50:345–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandhu SV, Narang RS, Jawanda M, et al. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour associated with dentigerous cyst of the maxillary antrum:a rare entity. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2010;14:24–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]